Eastern Orthodoxy in Montenegro

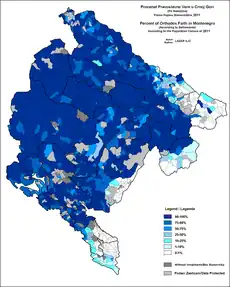

Eastern Orthodoxy in Montenegro refers to adherents, religious communities, institutions and organizations of Eastern Orthodox Christianity in Montenegro. It is the largest Christian denomination in the country. According to the latest census of 2011, 446,858 citizens of Montenegro (72.07%) registered as Eastern Orthodox Christians. The majority of Eastern Orthodox people in Montenegro are adherents of the Serbian Orthodox Church. A minor percentage supports the noncanonical and unrecognized Montenegrin Orthodox Church, which has the status of a religious non-governmental organization (NGO) since its founding in 1993.[1][2][3]

The current Metropolitan of Montenegro and primate of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Montenegro is Joanikije II, who serves as 56th head since the establishment of the diocese in 1219. The seat of the diocese is the Cetinje Monastery, since 1484.

Demographics

According to the 2011 official census, of the total 446,858 Eastern Orthodox Christians in Montenegro, there are: 246,733 ethnic Montenegrins (55.22%), 175,052 of Montenegrin Serbs (39.17%) and 25,073 of other ethnic groups (5.61%)

Serbian Orthodox Church in Montenegro

Four eparchies (dioceses) of the Serbian Orthodox Church cover the territory of Montenegro, two of them being entirely within its borders, and two partially:

- Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral, with seat in Cetinje Monastery,[4]

- Eparchy of Budimlja and Nikšić, with seat in Đurđevi Stupovi near Berane,[5]

- Eparchy of Mileševa, partially covers northwestern region of Montenegro, mainly the Pljevlja Municipality, and southwestern region of neighboring Serbia,

- Eparchy of Zahumlje and Herzegovina, also covers a small coastal region of Sutorina, Herceg Novi Municipality in southwestern corner of Montenegro.

In 2006, the Bishops' Council of the Serbian Orthodox Church decided to form a regional Bishops' Council for Montenegro, consisted of bishops whose dioceses cover the territory of Montenegro. By the same decision, Metropolitan of Montenegro and the Littoral was appointed president of the regional Bishops' Council.[6] The 17th-century Ostrog monastery is a religious landmark of Montenegro and the most popular pilgrimage site.[7]

Independent churches and religious NGOs

In modern times, some independent groups and organizations emerged within the wider scope of Eastern Orthodoxy in Montenegro, challenging the traditional position of the canonical Serbian Orthodox Church in the country. Alternative religious movements are focused mainly on the creation of a separate and independent (autocephalous) Orthodox Church in Montenegro, receiving so far a limited support from the public.

Montenegrin Orthodox Church (1993)

In 1993, a group led by recalled Orthodox Church in America and Serbian Orthodox monk, Antonije Abramović founded a separate religious organization, known as the Montenegrin Orthodox Church, at time receiving support from the Liberal Alliance of Montenegro, a minor political party that advocated the independence of Montenegro.[8] Antonije was proclaimed Metropolitan of Montenegro by his supporters, but his movement failed to gain any significant support. It remained unrecognized, and was labelled as noncanonical. In 1996, he was succeeded by Miraš Dedeić, controversial priest recalled by canonical Eastern Orthodox Churches back in early 1990s, Dedeić tried to reorganize MOC, hoping that state independence of Montenegro, achieved in 2006, would secure wider political support for his organization.[9] The MOC (1993) has been recognized as a religious NGO since 2001.

Montenegrin Orthodox Church (2018)

In 2018, a group of priests of the Montenegrin Orthodox Church (MOC) split and formed an organization.[10] This split was headed by Vladimir Lajović, who after the split became, in June 2018, an archimandrite under the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Church of Italy (Italian: Chiesa Ortodossa d'Italia), a schism of the Orthodox Church in Italy which itself is under the jurisdiction of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kyiv Patriarchate.[10][11]

See also

References

- Cattaruzza & Michels 2005, p. 235-253.

- Morrison & Čagorović 2014, p. 151-170.

- Džankić 2016, p. 110–129.

- Official Pages of the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral

- Official Pages of the Eparchy of Budimlja and Nikšić

- Communique of the Diocesan Council of the Orthodox Church in Montenegro (2010)

- Bataković 2005, p. 122.

- Buchenau 2014, p. 85.

- Džankić 2016, p. 120-121.

- Večernje novosti (2018): Raskol raskolnika: Crnogorska pravoslavna crkva se podelila u dve frakcije

- Chiesa Ortodossa d' Italia: Organizzazione

Sources

- Aleksov, Bojan (2014). "The Serbian Orthodox Church". Orthodox Christianity and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Southeastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 65–100.

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme.

- Buchenau, Klaus (2014). "The Serbian Orthodox Church". Eastern Christianity and Politics in the Twenty-First Century. London-New York: Routledge. pp. 67–93.

- Cattaruzza, Amaël; Michels, Patrick (2005). "Dualité orthodoxe au Monténégro". Balkanologie: Revue d'études pluridisciplinaires. 9 (1–2): 235–253.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Džankić, Jelena (2016). "Religion and Identity in Montenegro". Monasticism in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Republics. London-New York: Routledge. pp. 110–129.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2008). "Serbian Orthodox Church". Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 519–520.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983a). History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983b). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan, ed. (1989). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 7. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Morrison, Kenneth (2009). Montenegro: A Modern History. London-New York: I.B.Tauris.

- Morrison, Kenneth; Čagorović, Nebojša (2014). "The Political Dynamics of Intra-Orthodox Conflict in Montenegro". Politicization of Religion, the Power of State, Nation, and Faith: The Case of Former Yugoslavia and its Successor States. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 151–170. doi:10.1057/9781137477866_7. ISBN 978-1-349-50339-1.

- Pavlovich, Paul (1989). The History of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Serbian Heritage Books.

- Popović, Svetlana (2002). "The Serbian Episcopal sees in the thirteenth century". Старинар (51: 2001): 171–184.

- Radić, Radmila (2007). "Serbian Christianity". The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 231–248.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Sotirović, Vladislav B. (2011). "The Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in the Ottoman Empire: The First Phase (1557–94)". 25 (2): 143–169.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Wachtel, Andrew B. (2004). "How to Use a Classic: Petar Petrović-Njegoš in the Twentieth Century". Ideologies and National Identities: The Case of Twentieth-Century Southeastern Europe. Budapest: Central European University Press. pp. 131–153.

External links

- Official Pages of the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral

- Official Pages of the Eparchy of Budimlja and Nikšić

- Statement of The Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Coastlands (2009)

- Mass service held in Montenegro in defense of Serbian Church (2019)

- Freedom of Religion or Belief in Montenegro: Conclusions (2019)