Economic liberalisation in India

The economic liberalisation in India refers to the series of policy changes aimed at opening up the country's economy to the world, with the objective of making it more market-oriented and consumption-driven. The goal was to expand the role of private and foreign investment, which was seen as a means of achieving economic growth and development.[1][2] Although some attempts at liberalisation were made in 1966 and the early 1980s, a more thorough liberalisation was initiated in 1991.

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Neoliberalism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

The liberalisation process was prompted by a balance of payments crisis that had led to a severe recession, and the need to fulfill structural adjustment programs required to receive loans from international financial institutions such as the IMF and World Bank. The crisis in 1991 served as a catalyst for the government to initiate a more comprehensive economic reform agenda, including Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation referred to as LPG reforms.

The reform process had significant effects on the Indian economy, leading to an increase in foreign investment and a shift towards a more services-oriented economy. The impact of India's economic liberalisation policies on various sectors and social groups has been a topic of ongoing debate. While the policies have been credited with attracting foreign investment, some have expressed concerns about their potential negative consequences. One area of concern has been the environmental impact of the liberalisation policies, as industries have expanded and regulations have been relaxed to attract investment. Additionally, some critics argue that the policies have contributed to widening income inequality and social disparities, as the benefits of economic growth have not been equally distributed across the population.

Pre-liberalisation policies

Indian economic policy after independence was influenced by the colonial experience (which was exploitative in nature) and by those leaders', particularly prime minister Nehru's exposure to Fabian socialism.[3] Under the Congress party governments of Nehru, and his successors policy tended towards protectionism, with a strong emphasis on import substitution industrialization under state monitoring, state intervention at the micro level in all businesses especially in labour and financial markets, a large public sector, business regulation, and central planning.[4] Five-Year Plans of India resembled central planning in the Soviet Union. Under the Industrial Development Regulation Act of 1951, steel, mining, machine tools, water, telecommunications, insurance, and electrical plants, among other industries, were effectively nationalised. Elaborate licenses, regulations, and bureaucracy were also introduced to ensure that businesses operated within the framework of national goals and priorities. These policies were intended to promote self-sufficiency and reduce the country's dependence on foreign powers. The resulting economic system is commonly referred to as Dirigism, characterized by state intervention and central planning. These policies were seen be some as restraining economic growth.[5][6]

Only four or five licences would be given for steel, electrical power and communications, allowing license owners to build huge and powerful empires without competition.[7] A significant public sector emerged in India during this period, where the state took ownership of several key industries. These state-owned enterprises were not necessarily expected to generate a profit, but instead to serve social and developmental objectives. As a result, they sometimes incurred losses without being shut down. However, this approach also meant that the government was responsible for covering the losses, which contributed to the financial burden on the state.[7] The lack of competition due to licensing and slow business growth resulted in poor infrastructure development in some areas, which further impeded economic progress.[7]

During the brief rule by the Janata party in late 1970s, the government seeking to promote economic self-reliance and indigenous industries, required multi-national corporations to go into partnership with Indian corporations. The policy proved controversial, diminishing foreign investment and led to the high-profile exit of corporations such as Coca-Cola and IBM from India.[8]

In the 1990s, Coca-Cola re-entered the Indian market and faced competition from domestic cola companies such as Pure Drinks Group and Parle Bisleri. However, the multinational company's marketing and distribution networks enabled it to gain a significant share of the market, leading to financial difficulties for some domestic companies, ultimately resulting in the decline and closure of much of Pure Drinks Group bottling plants and Parle Bisleri selling much of its business to Coca-Cola.

The annual growth rate of the Indian economy had averaged around 4% from the 1950s to 1980s, while per-capita income growth averaged 1.3%.[9]

Reforms before 1991

1966 liberalisation attempt

In 1966, due to rapid inflation caused by an increasing budget deficit accompanying the Sino-Indian War and severe drought, the Indian government was forced to seek monetary aid from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank.[10] Pressure from aid donors caused a shift towards economic liberalisation, wherein the rupee was devalued to combat inflation and cheapen exports and the former system of tariffs and export subsidies was abolished.[11] However, a second poor harvest and subsequent industrial recession helped fuel political backlash against liberalisation, characterised by resentment at foreign involvement in the Indian economy and fear that it might signal a broader shift away from socialist policies.[12] As a result, trade restrictions were reintroduced and the Foreign Investments Board was established in 1968 to scrutinise companies investing in India with more than 40% foreign equity participation.[11]

World Bank loans continued to be taken for agricultural projects since 1972, and these continued as international seed companies that were able to enter Indian markets after the 1991 liberalisation.[13]

Economic reforms during the 1980s

As it became evident that the Indian economy was lagging behind its East and Southeast Asian neighbours, the governments of Indira Gandhi and subsequently Rajiv Gandhi began pursuing economic liberalisation.[14] The governments loosened restrictions on business creation and import controls while also promoting the growth of the automobile, digitalization, telecommunications and software industries.[15] Reforms under lead to an increase in the average GDP growth rate from 2.9 percent in the 1970s to 5.6 per cent, although they failed to fix systemic issues with the Licence Raj.[14] Despite Rajiv Gandhi's dream for more systemic reforms, the Bofors scandal tarnished his government's reputation and impeded his liberalisation efforts.[16]

Chandra Shekhar Singh reforms

The Chandra Shekhar government (1990–91) took several significant steps towards liberalisation and laid its foundation.[17]

Liberalisation of 1991

Crisis leading to reforms

By 1991, India still had a fixed exchange rate system, where the rupee was pegged to the value of a basket of currencies of major trading partners. India started having balance of payments problems in 1985, and by the end of 1990, the state of India was in a serious economic crisis. Although a fixed exchange rate system helped India to achieve currency stability, it also necessitated that the Indian Government utilize its foreign exchange reserves in the event of currency pressures in order to avoid a breach of the currency peg. The government was close to default,[18][19] its central bank had refused new credit, and foreign exchange reserves had reduced to the point that India could barely finance two weeks' worth of imports.

Liberalisation of 1991

The collapse of the Chandra Shekhar government in the midst of the crisis and the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi led to the election of a new Congress government led by P. V. Narasimha Rao.[20] He selected Amar Nath Verma to be his Principal Secretary and Manmohan Singh to be finance minister and gave them complete support in doing whatever they thought was necessary to solve the crisis.[20] Verma helped draft the New Industrial Policy alongside Chief Economic Advisor Rakesh Mohan, and it laid out a plan to foster Indian industry in five points.[21][22]

- Firstly, it abolished the License Raj by removing licensing restrictions for all industries except for 18 that "related to security and strategic concerns, social reasons, problems related to safety and overriding environmental issues."[21]

- To incentivise foreign investment, it laid out a plan to pre-approve all investment up to 51% foreign equity participation, allowing foreign companies to bring modern technology and industrial development.[20][21] To further incentivise technological advancement, the old policy of government approval for foreign technology agreements was scrapped.

- The fourth point proposed to dismantle public monopolies by floating shares of public sector companies and limiting public sector growth to essential infrastructure, goods and services, mineral exploration, and defense manufacturing.[20][21]

- Finally the concept of an MRTP company, where companies whose assets surpassed a certain value were placed under government supervision, was scrapped.[20][23]

Meanwhile, Manmohan Singh worked on a new budget that would come to be known as the Epochal Budget.[24] The primary concern was getting the fiscal deficit under control, and he sought to do this by curbing government expenses. Part of this was the disinvestment in public sector companies, but accompanying this was a reduction in subsidies for fertilizer and abolition of subsidies for sugar.[25] He also dealt with the depletion of foreign exchange reserves during the crisis with a 19 per cent devaluation of the rupee with respect to the US dollar, a change which sought to make exports cheaper and accordingly provide the necessary foreign exchange reserves.[26][27] The devaluation made petroleum more expensive to import, so Singh proposed to lower the price of kerosene to benefit the poorer citizens who depended on it while raising petroleum prices for industry and fuel.[28] On 24 July 1991, Manmohan Singh presented the budget alongside his outline for broader reform.[24] During the speech he laid out a new trade policy oriented towards promoting exports and removing import controls.[29] Specifically, he proposed limiting tariff rates to no more than 150 percent while also lowering rates across the board, reducing excise duties, and abolishing export subsidies.[29]

In August 1991, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Governor established the Narasimham Committee to recommend changes to the financial system.[30] Recommendations included reducing the statutory liquidity ratio (SLR) and cash reserve ratio (CRR) from 38.5% and 15% respectively to 25% and 10% respectively, allowing market forces to dictate interest rates instead of the government, placing banks under the sole control of the RBI, and reducing the number of public sector banks.[31] The government heeded some of these suggestions, including cutting the SLR and CRR rates, liberalizing interest rates, loosening restrictions on private banks, and allowing banks to open branches free from government mandate.[32][25]

On 12 November 1991, based on an application from the Government of India, World Bank sanctioned a structural adjustment loan/credit that consisted of two components – an IBRD loan of $250 million to be paid over 20 years, and an IDA credit of SDR 183.8 million (equivalent to $250 million) with 35 years maturity, through India's ministry of finance, with the President of India as the borrower. The loan was meant primarily to support the government's program of stabilization and economic reform. This specified deregulation, increased foreign direct investment, liberalisation of the trade regime, reforming domestic interest rates, strengthening capital markets (stock exchanges), and initiating public enterprise reform (selling off public enterprises).[33] As part of a bailout deal with the IMF, India was forced to pledge 20 tonnes of gold to Union Bank of Switzerland and 47 tonnes to the Bank of England and Bank of Japan.[34]

The reforms drew heavy scrutiny from opposition leaders. The New Industrial Policy and 1991 Budget was decried by opposition leaders as "command budget from the IMF" and worried that withdrawal of subsidies for fertilizers and hikes in oil prices would harm lower and middle-class citizens.[24] Critics also derided devaluation, fearing it would worsen runaway inflation that would hit the poorest citizens the hardest while doing nothing to fix the trade deficit.[35] In the face of vocal opposition, the support and political will of the prime minister was crucial in order to see through the reforms.[36] Rao was often referred to as Chanakya for his ability to steer tough economic and political legislation through the parliament at a time when he headed a minority government.[37][38]

Impact

Reforms in India in the 1990s and 2000s aimed to increase international competitiveness in various sectors, including auto components, telecommunications, software, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, research and development, and professional services. These reforms included reducing import tariffs, deregulating markets, and lowering taxes, which led to an increase in foreign investment and high economic growth. From 1992 to 2005, foreign investment increased by 316.9%, and India's GDP grew from $266 billion in 1991 to $2.3 trillion in 2018.[39][40]

According to one study, wages rose on the whole, as well as wages as the labor-to-capital relative share.[41] GDP, however, has been criticized by some to be flawed as it does not show inequality or living standards.

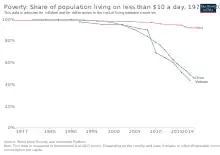

Extreme poverty reduced from 36 percent in 1993–94 to 24.1 percent in 1999–2000.[42] However, these poverty figures have been criticised as not representing the true picture of poverty.[43] According to one report, the wealthiest one percent of the country earns between 5 and 7 percent of the national income, while approximately 15 percent of the working population earns less than ₹ 5,000 (about $64) per month.[44]

The liberalisation policies have also been criticised for increasing income inequality, concentrating wealth, worsening rural living standards, causing unemployment, and leading to an increase in farmer suicides.[45][46]

India also increasingly integrated its economy with the global economy. The ratio of total exports of goods and services to GDP in India approximately doubled from 7.3 percent in 1990 to 14 percent in 2000.[47] This rise was less dramatic on the import side but was significant, from 9.9 percent in 1990 to 16.6 percent in 2000. Within 10 years, the ratio of total goods and services trade to GDP rose from 17.2 percent to 30.6 percent.[42] India, however, continues to have a trade deficit, relying on foreign capital to maintain its balance of payments and as such, makes it vulnerable to external shocks.[48]

Foreign investment in India in form of foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, and investment raised on international capital markets increased significantly, from US$132 million in 1991–92 to $5.3 billion in 1995–96.

However, the liberalization did not benefit all parts of India equally, with urban areas benefiting more than rural areas.[49] Additionally, some states with pro-worker labor laws saw slower industry expansion than those with pro-employer labor laws.

After the reforms, life expectancy and literacy rates continued to increase at roughly the same rate as before the reforms.[50][51] For the first 10 years after the 1991 reforms, GDP also continued to increase at roughly the same rate as before the reforms.[52][53]

By 1997, it became evident that no governing coalition would try to dismantle liberalisation, although governments avoided taking on trade unions and farmers on contentious issues such as reforming labour laws and reducing agricultural subsidies.[54] By the turn of the 21st century, India had progressed towards a free-market economy, with a substantial reduction in state control of the economy and increased financial liberalisation.[55]

Institutions like the OECD which promote neoliberal free-market economics[56] applauded the changes:

Its annual growth in GDP per capita accelerated from just 1¼ per cent in the three decades after Independence to 7½ per cent currently, a rate of growth that will double the average income in a decade.... In service sectors where government regulation has been eased significantly or is less burdensome—such as communications, insurance, asset management and information technology—output has grown rapidly, with exports of information technology-enabled services particularly strong. In those infrastructure sectors which have been opened to competition, such as telecoms and civil aviation, the private sector has proven to be extremely effective and growth has been phenomenal.

In 2006 India recorded its highest GDP growth rate of 9.6% [58] becoming the second fastest growing major economy in the world, next only to China.[59] The growth rate slowed significantly in the first half of 2012.[60]

The economy then rebounded to 7.3% growth in 2015, 7.9% in 2015 and 8.2% in 2016 before falling to 6.7% in 2017, 6.5% in 2018 and 4% in 2019.[61]

Sluggish growth since 2016

_India_and_China.png.webp)

India's GDP growth experienced a slowdown since 2016 due to a combination of factors such as:

- Demonetization: In November 2016, the Indian government invalidated high denomination currency notes (₹500 and ₹1,000) with the stated goal of combating corruption and black money. This move disrupted the cash-dependent informal sector, causing a contraction in economic activity and a slowdown in GDP growth.[63]

- Goods and Services Tax (GST) implementation: The introduction of the GST in July 2017 aimed to streamline India's tax system. However, challenges in its implementation, including complex rules, confusion about tax rates, and technology issues led to disruptions in supply chains and compliance burdens for small businesses which negatively impacted GDP growth. GST is also sometimes considered a regressive tax as it arguably disproportionately affects the poor more than the rich. It also lead to a decrease in fiscal autonomy of Indian state governments.[64]

- Banking sector woes: The Indian banking sector has been grappling with a high level of non-performing assets (NPAs) or bad loans. This has led to a credit crunch, with banks becoming more cautious in lending, which in turn has constrained investment and growth in the country.[65]

- Global economic factors: The US-China trade war which continued under Joe Biden, volatile oil prices, and a slowdown in global economic growth have impacted India's economy. These factors have contributed to reduced exports and investments, as well as currency volatility.[66]

- Weak private investment: India has experienced a decline in private investment, a perceived "unfavourable" business environment, and the aforementioned credit crunch. This has had a dampening effect on GDP growth.

- Rural distress and consumption slowdown: The rural economy in India, which largely depends on agriculture, has been under stress due to low crop prices, high input costs, poor rainfall, and mounting farmer debt. This has led to reduced rural consumption and a slowdown in overall consumer spending.[67]

- Income inequality: The increase in income inequality in India as a result of economic reforms has contributed to a decrease in the purchasing power of low-income individuals. This decrease in purchasing power has led to a relatively low demand for goods and services in certain sectors.[68]

Later reforms

During the Atal Bihari Vajpayee administration, there were extensive liberal reforms, with the NDA Coalition beginning the privatisation of government-owned businesses, including hotels, VSNL, Maruti Suzuki, and airports. The coalition also implemented tax reduction policies, enacted fiscal policies aimed at reducing deficits and debts, and increased initiatives for public works.[69][70]

In 2011, the second UPA Coalition Government led by Manmohan Singh proposed the introduction of 51% Foreign Direct Investment in the retail sector. However, the decision was delayed due to pressure from coalition parties and the opposition, and it was ultimately approved in December 2012.[71]

After coming to power in 2014, the Narendra Modi led government launched several initiatives aimed at promoting economic growth and development. One of the notable programs was the "Make in India" campaign, which sought to encourage domestic and foreign companies to invest in manufacturing and production in India. The program aimed to create employment opportunities and enhance the country's manufacturing capabilities.

Privatisation of airports

After 2014, the Indian government under the leadership of Prime Minister Narendra Modi initiated the privatisation of airports in India as part of its policy of economic liberalisation and development. Under this policy, the Airports Authority of India (AAI) has been engaging in Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) with private companies for the development, management, and operation of airports in India. This has led to the privatisation of several airports across the country, including those in Ahmedabad, Lucknow, Jaipur, Guwahati, Thiruvananthapuram, and Mangaluru.[72]

While the privatisation of airports has been hailed as a step towards modernisation and efficiency, there have also been concerns about the potential impact on workers and the local communities. Critics have argued that the privatisation of airports may lead to job losses and a decline in wages, and that the focus on profit-making may lead to neglect of social and environmental concerns.There have also been controversies around the awarding of contracts to private companies, with allegations of corruption and favouritism in the selection process. However, the government has defended its privatisation policy as a necessary step towards achieving economic growth and development in the country.[73]

Under the second NDA Government, the coal industry was opened up through the passing of the Coal Mines (Special Provisions) Bill of 2015. This effectively ended the state monopoly over the mining of the coal sector and opened it up for private, foreign investments, as well as private sector mining of coal.[72]

In the 2016 budget session of Parliament, the Narendra Modi led NDA Government pushed through the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code to create time-bound processes for insolvency resolution of companies and individuals.[74]

On 1 July 2017, the NDA Government under Modi approved the Goods and Services Tax Act, which had been first proposed 17 years earlier under the NDA Government in 2000. The act aimed to replace multiple indirect taxes with a unified tax structure.[75][76]

In 2019, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced a reduction in the base corporate tax rate from 30% to 22% for companies that do not seek exemptions, and the tax rate for new manufacturing companies was reduced from 25% to 15%. The Indian government proposed agricultural and labor reforms in 2020, but faced backlash from farmers who protested against the proposed agricultural bills. Eventually, due to the sustained protests, the government repealed the agricultural bills.[77][78]

Criticisms

The liberalisation of the Indian economy was followed by a large increase in inequality with the income share of the top 10% of the population increasing from 35% in 1991 to 57.1% in 2014. Likewise, the income share of the bottom 50% decreased from 20.1% in 1991 to 13.1% in 2014.[79] It has also been criticised for decreasing rural living standards, rural employment and an increase in farmer suicides.[46]

Poverty continues to persist in India, before the COVID-19 pandemic there were 59 million Indians living below $2 a day and 1,162 million living between $2.01 and $10 a day.[80] Low government expenditure on healthcare has resulted in a healthcare quality divide between rich and poor as well as between the rural and urban population.[81]

Growth during the 1980s was higher than in the preceding decades but fragile. It not only culminated in a crisis in June 1991 but also exhibited significantly higher variance than growth in the 1990s. Central to the high growth rate in the 1980s was the super high growth of 7.6 percent during 1988–1991.[82]

The fragile but faster growth during the 1980s took place in the context of significant reforms throughout the decade but especially starting in 1985.The liberalization pushed industrial growth to a hefty 9.2 percent during the crucial high growth period of 1988–1991.[83]

After 1991, the Indian government removed some restrictions on imports of agricultural products causing a price crash while cutting subsidies for the farmers to keep government intervention to the minimum as per neoliberal ideals causing further farmer distress.[46]

2020–2021 Indian farmers' protests forced the Indian government to repeal three laws meant to further liberalize Indian agriculture sector.[84]

India is highly dependent on indirect taxes, especially the tax levied on the sale and manufacture of goods and services that ordinary Indians depend upon.[85]

The liberalization of the economy made India more vulnerable to global market forces, such as fluctuations in commodity prices, exchange rates and global demand for exports. This increased the country's dependence on global market forces, as it became more susceptible to external shocks and economic crises.[86] A commonly cited example of this is the 2008 Financial Crisis; although the Indian banking sector had low exposure to US banking sector, the crisis still had a negative impact on the Indian economy due to lower global demand, decline in foreign investment and tightening of credit.[87]

References

- India – Structural Adjustment Credit Project (English) – Presidents report (Report). World Bank. 12 November 1991. p. 1.

- "Structural adjustments in India – a reportof the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG". World Bank. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Misra, O.P (1995). Economic thought of Gandhi and Nehru: a comparative analysis. New Delhi: MD Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 978-81-85880-71-6.

- Kelegama, Saman; Parikh, Kirit (2000). "Political Economy of Growth and Reforms in South Asia". Second Draft. Archived from the original on 11 February 2006.

- Chandrasekhar, C. P. (2012), Kyung-Sup, Chang; Fine, Ben; Weiss, Linda (eds.), "From Dirigisme to Neoliberalism: Aspects of the Political Economy of the Transition in India" (PDF), Developmental Politics in Transition: The Neoliberal Era and Beyond, International Political Economy Series, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 140–165, doi:10.1057/9781137028303_8, ISBN 978-1-137-02830-3, retrieved 4 September 2020

- Mazumdar, Surajit (2012). "Industrialization, Dirigisme and Capitalists: Indian Big Business from Independence to Liberalization". mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- "India: the economy". BBC. 12 February 1998.

- Shashi Tharoor (2006). India: From Midnight To Millennium and Beyond. Arcade Publishing. pp. 164–66. ISBN 978-1-55970-803-6.

- "Redefining The Hindu Rate of Growth". The Financial Express. 12 April 2004.

- Srinivas, V. (27 March 2018). "India's IMF Programmes—1966 and 1981: An Analytical Review". Indian Journal of Public Administration. 64 (2): 219–227. doi:10.1177/0019556117750897. ISSN 0019-5561. S2CID 188184832.

- Mukherji, R. (2000). India's Aborted Liberalization-1966. Pacific Affairs, 73(3), 377–379. doi:10.2307/2672025

- Bhagwati, Jagdish N.; Srinivasan, T. N. (1975). Foreign Trade Regimes and Economic Development: India. The National Bureau of Economic Research. pp. 151–153. ISBN 0-87014-531-2.

- Sainath, P. Everybody loves a good drought. Sage Publications.

- Mohan, Rakesh (2018). India Transformed: 25 Years of Economic Reforms. Brookings Institution. pp. 68–71. ISBN 9780815736622.

- History of Computing in India: 1955–2010, Rajaraman, V.

- "Bofors prevented Rajiv Gandhi from taking up liberalisation". The Economic Times. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- "Clipping of the New Indian Express Group – the New Indian Express-Chennai". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- India's Pathway through Financial Crisis Archived 12 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Arunabha Ghosh. Global Economic Governance Programme. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- What Caused the 1991 Currency Crisis in India? Archived 2 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine, IMF Staff Papers, Valerie Cerra and Sweta Chaman Saxena.

- Mohan, Rakesh. (2018). India Transformed : Twenty-Five Years of Economic Reforms. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. pp. 44–49. ISBN 978-0-8157-3662-2. OCLC 1056070747.

- Verma, A. N. (1991). Statement on Industrial Policy (India, Ministry of Industry). New Delhi: Government of India.

- Mital, Ankit (27 August 2016). "The people behind the Great Men of 1991". Livemint. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act 1970 – GKToday". 14 September 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- "Everything about Manmohan Singh's Epochal Budget that marked the beginning of economic liberalisation". Free Press Journal. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- "1991: Economic Reforms". India Before 1991. 18 January 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- "Devaluation of the Rupee: Tale of Two Years, 1966 and 1991" (PDF). 29 March 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Jadhav, N. (1991). "Rupee Devaluation: Real Issues". Economic and Political Weekly. 26 (36): 2119–2120. JSTOR 41626979.

- Singh, M. (24 July 1991). Budget 1991–1992 [PDF]. New Delhi: Government of India Ministry of Finance. pp. 11.

- Singh, M. (24 July 1991). Budget 1991–1992 [PDF]. New Delhi: Government of India Ministry of Finance.

- "First Narasimham Committee – GKToday". 21 April 2011. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- Akrani, Gaurav. "Narasimham Committee Report 1991 1998 – Recommendations". Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- "First Narasimham Committee – GKToday". 21 April 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- "World bank report P-5678-IN – report of the IBRD and IDA on a proposed structural adjustment loan to India" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Economic Crisis Forcing Once Self-Reliant India to Seek Aid, The New York Times, 29 June 1991

- "Wishful Thinking on Devaluation". Economic and Political Weekly. 26 (29): 1724. 1991. JSTOR 41498462.

- Balachandran, Manu (6 October 2016). "The real architect of India's economic reforms wasn't Manmohan Singh". Quartz India. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- V. Venkatesan (14 January 2005). "Obituary: A scholar and a politician". Frontline. 22 (1). Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- PV Narasimha Rao Passes Away. Retrieved 7 October 2007. Archived 1 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Dutta, M. K. and Sarma, Gopal Kumar, Foreign Direct Investment in India Since 1991: Trends, Challenges and Prospects (1 January 2008).

- Mudgill, Amit. "Since 1991, Budget size grew 19 times, economy 9 times; your income 5 times". The Economic Times. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Leblebicioğlu, Asl; Weinberger, Ariel (3 December 2020). "Openness and factor shares: Is globalization always bad for labor?". Journal of International Economics. 128: 103406. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2020.103406. ISSN 0022-1996. S2CID 229432582.

- "Impact of reforms". India Before 1991. 18 January 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- Hickel, Jason (1 November 2015). "Could you live on $1.90 a day? That's the international poverty line". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- "Earning Rs 25,000 Per Month? You Are In India's Top 10%: Report". NDTV.com. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- Ghosh, Jayati (15 December 2020). "Hindutva, Economic Neoliberalism and the Abuse of Economic Statistics in India". South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (in French) (24/25). doi:10.4000/samaj.6882. ISSN 1960-6060. S2CID 230588392.

- "Please Mind The Gap: Winners and Losers of Neoliberalism in India". E-International Relations. 11 March 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- Local industrialists against multinationals. Ajay Singh and Arjuna Ranawana. Asiaweek. Retrieved 2 March 2007.

- Singh, Sarita Chaganti (15 February 2023). "India's January merchandise trade deficit hits 1-year low of $17.75 bln". Reuters. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- Aghion, Philippe; Burgess, Robin; Redding, Stephen J.; Zilibotti, Fabrizio (2008). "The Unequal Effects of Liberalization: Evidence from Dismantling the License Raj in India". The American Economic Review. 98 (4): 1397–1412. doi:10.1257/aer.98.4.1397. ISSN 0002-8282. JSTOR 29730127. S2CID 966634.

- "Life expectancy at birth, total (Years) – India, China | Data".

- "Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above) – India | Data".

- "GDP growth (Annual %) – India | Data".

- "GDP (Current US$) – India | Data".

- "That old Gandhi magic". The Economist. 27 November 1997. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Kumar 2005, p. 1037

- "Why open markets matter – OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- "Economic survey of India 2007: Policy Brief" (PDF). OECD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2011.

- "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "The India Report" (PDF). Astaire Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2009.

- "India growth rate slows to 5.3% in first quarter". BBC. 31 May 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "GDP growth (annual %) – India | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- "World Bank Open Data". World Bank Open Data. Retrieved 9 September 2023.

- Giri Subramaniam (2020). "The Supply-Side Effects of India's Demonetization". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3472758.

- "The Impact of India's New GST Tax on the Economy - In the Trenches - IMF F&D Magazine - June 2018 | Volume 55 | Number 2". IMF. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- "The Public-Sector Banking Crisis In India". www.oliverwyman.com. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- Cheng, Natalie Fang Ling; Hasanov, Akram Shavkatovich; Poon, Wai Ching; Bouri, Elie (1 April 2023). "The US-China trade war and the volatility linkages between energy and agricultural commodities". Energy Economics. 120: 106605. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106605. ISSN 0140-9883.

- Reddy, A. Amarender; Bhattacharya, Anindita; Reddy, S. Venku; Ricart, Sandra (12 November 2021). "Farmers' Distress Index: An Approach for an Action Plan to Reduce Vulnerability in the Drylands of India". Land. 10 (11): 1236. doi:10.3390/land10111236. ISSN 2073-445X.

- "Economic Consequences of Income Inequality".

- J. Bradford DeLong (2001). "India Since Independence: An Analytic Growth Narrative" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- "5 economic decisions by Atal Bihari Vajpayee that changed the face of India". Moneycontrol.

- "End of policy paralysis: Govt approves 51% FDI in multi-brand retail". Zeenews.india.com. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "Parliament boost to Modi's plans: Coal, mining bills passed by Rajya Sabha". indiatoday.intotoday.in. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "'Modi's Rockefeller': Gautam Adani and the concentration of power in India". Financial Times. 13 November 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- "Bankruptcy code biggest economic reform after GST: Finance Ministry". The Economic Times. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- "F. .No. CBEC-20/05/01/2018-GST Government of India …" (PDF). cbic.gov.in/. Ministry of Finance, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2018.

- "GST Launch Time Midnight Parliament Session". Hindustan Times. 30 June 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "Indian lawmakers pass farm bills amid uproar in Parliament". AP NEWS. 13 May 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- "Explained: In the three new labour codes, what changes for workers & hirers?". The Indian Express. 27 September 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- "India". WID – World Inequality Database. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- Kochhar, Rakesh. "In the pandemic, India's middle class shrinks and poverty spreads while China sees smaller changes". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- "Private Healthcare in India: Boons and Banes". Institut Montaigne. Retrieved 31 January 2022.

- https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2004/wp0443.pdf

- "On this day in 1991: A landmark budget that changed India's fortunes". The Economic Times. 24 July 2022. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- "Bowing to protests, India's Modi agrees to repeal farm laws". AP NEWS. 19 November 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- "inequality Kills: India Supplement 2022". www.oxfamindia.org. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- Sekhar, C. S. C. (2004). "Agricultural Price Volatility in International and Indian Markets". Economic and Political Weekly. 39 (43): 4729–4736. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4415712.

- "Impact of the international banking crisis on the Indian financial system" (PDF).

Works cited

- Kumar, Dharma (2005). The Cambridge Economic History of India, Volume II : c. 1757–2003. New Delhi: Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-2710-2.

- "Economic reforms in India: Task force report" (PDF). University of Chicago. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2009.

External links

- For a short educational video of the "economic history of India".

- Nick Gillespie (2009). "What Slumdog Millionaire can teach Americans about economic stimulus". Reason. Archived from the original on 13 June 2009. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- Gurcharan Das (2006). "The India Model". The Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009.

- Ravinder Kaur (2012). "India Inc. and its Moral Discontent". Economic and Political Weekly.

- Aditya Gupta (2006). "How wrong has the Indian Left been about economic reforms?" (PDF). Centre for Civil Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2009.

- "The India Report" (PDF). Astaire Research <<doesn't work>>. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2009.