Edmund Crouchback

Edmund, 1st Earl of Lancaster (16 January 1245 – 5 June 1296), also known by his epithet Edmund Crouchback, was a member of the royal Plantagenet Dynasty and the founder of the first House of Lancaster. He was Earl of Leicester (1265–1296), Lancaster (1267–1296) and Derby (1269–1296) in England, and Count Palatine of Champagne (1276–1284) in France.

| Edmund Crouchback | |

|---|---|

Effigy and monument of Edmund Crouchback, Westminster Abbey | |

| Earl of Lancaster, Leicester, and Derby | |

| Predecessor | None (position established) |

| Successor | Thomas of Lancaster |

| Born | 16 January 1245 London, England |

| Died | 5 June 1296 (aged 51) Bayonne, Duchy of Aquitaine |

| Burial | 24 March 1301 |

| Spouse | |

| Issue more... | Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster |

| House | Plantagenet (by birth) Lancaster (founder) |

| Father | Henry III of England |

| Mother | Eleanor of Provence |

Named after the 9th-century saint, Edmund was the second surviving son of King Henry III of England and Eleanor of Provence and the younger brother of King Edward I of England, to whom he was loyal as a diplomat and warrior. In 1254, the 9-year-old Edmund became involved in the "Sicilian business", in which his father accepted a papal offer granting the Kingdom of Sicily to Edmund, who made preparations to become king. However, Henry III could not provide funds for the operation, prompting the Papacy to withdraw the grant and give it to Edmund's uncle, Charles I of Anjou. The "Sicilian business" outraged the barons led by the Earl of Leicester and Edmund's uncle, Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, and was cited as one of the reasons for limiting Henry's power. Deterioration of relations between the barons and the king resulted in the Second Barons' War, in which the royal government, supported by Edmund, triumphed over the baronage following the death of Montfort in the Battle of Evesham in 1265.

Edmund received the lands and titles of Montfort and the defeated barons Nicholas Segrave, 1st Baron Segrave and Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby, and became Earl of Lancaster, Leicester and Derby. Primarily known as the earl of the first county, he eventually became the most powerful baron of England. Later, Edmund accompanied his elder brother Edward on his crusade in the Holy Land, where his epithet "Crouchback" originated from a corruption of 'cross back', referring to him wearing a stitched cross on his garments. Following the death of his first wife, Aveline de Forz, Edmund's aunt and Dowager Queen of France Margaret of Provence arranged his second marriage to Blanche of Artois, the recently widowed Queen Dowager of Navarre and the Countess of Champagne. With his second wife Blanche, Edmund governed Champagne as count palatine in the name of his stepdaughter Joan until she came of age. Edmund was active in supporting his family members, such as assisting Edward in conquering Wales, advocating for the claims of his aunt Margaret against his uncle Charles I of Anjou in his mother and aunt's homeland of Provence and managing Ponthieu on behalf of his sister-in-law, Eleanor of Castile.

When Edmund's stepson-in-law, King Philip IV of France, demanded Edward, who was also his vassal through Gascony, to come to Paris to answer charges of damages caused by English mariners in 1293, Edward sent Edmund to mediate the crisis to avert war. Edmund negotiated an agreement with Philip where France would occupy Gascony for 40 days, and Edward would marry Philip's half-sister, Margaret. When the 40 days were over, Philip tricked Edward and Edmund by refusing to relinquish control over Gascony, calling Edward to again answer for his charges. Edmund and Edward then renounced their homages to Philip and prepared for war against France. Edmund sailed for Gascony with his army and besieged the city of Bordeaux. Unable to pay his troops, Edmund was deserted by his army and retreated to Bayonne, where he died from illness in 1296. Edmund's body was brought back to England, where he was buried in Westminster Abbey in 1301.

Early years, 1245–1265

Birth and childhood

Edmund was born in London to King Henry III of England and Eleanor of Provence on 16 January 1245.[1] Henry named him after the martyred and canonised 9th-century East Anglian king, whom Henry prayed to for a second son.[2][3] He was a younger brother of Edward (later King Edward I of England), Margaret and Beatrice, and an elder brother of Catherine.[4] Edmund spent most of his childhood at Windsor Castle alongside his siblings. He grew emotionally attached to his father Henry, who rarely spent extended periods apart from his family.[5]

Sicilian business

In 1254, Henry accepted a papal offer from Pope Innocent IV to make Edmund the next king of Sicily.[6] Sicily had been ruled by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, who was a rival to Innocent for many years;[7] the papacy hoped for a friendlier ruler to succeed Frederick following his death in 1250.[8] For Henry, Sicily was a valuable prize for his son and would also provide a base to launch his planned crusades in the east.[9] Innocent tasked Henry with sending Edmund and an army to reclaim Sicily from Frederick's son, Manfred, King of Sicily, and to cover expenses and debts up to a total of £135,000, for which the papacy would provide assistance in funding.[10]

The nine-year-old Edmund made preparations to become king, sailing to Gascony with his mother, Eleanor, in May 1254.[11] In Bordeaux, on 3 October, Edmund granted his granduncle Count Thomas of Flanders the Principality of Capua before returning home in December of that year.[11] On 18 October 1255, Edmund received a ceremonial investiture in Sicily, where his father Henry styled him as king and presented him with a ring.[11][12] In January 1256, Edmund granted a reward to one of his Italian followers, and in April, he proposed marriage to Plaisance of Antioch, the queen of Cyprus and Lady of Beirut.[11] In April 1257, Henry paraded Edmund in Parliament dressed in Italian clothing to appeal for funds.[12][13] He also suggested marrying Edmund to a daughter of Manfred to resolve the 'Sicilian business' in the summer of that year.[11]

Prospects turned grim when Pope Alexander IV succeeded Innocent and faced military pressure from the Holy Roman Empire.[14] Alexander could no longer finance Henry's expenses and instead demanded that Henry pay £90,000 in debts to the Papacy as compensation for the war.[15] This was an enormous sum, and Henry found himself desperate for funds. He sought assistance from Parliament, but his request was denied. Despite further attempts, Parliament only granted partial funding to Henry.[16] Growing impatient, Alexander sent an envoy to Henry in 1258, threatening him with excommunication unless he paid his debts and sent an army to Sicily.[17] Failing to convince Parliament further,[18] Henry resorted to extorting money from the senior clergy, raising approximately £40,000.[19] Subsequently, at some point between 1258 and 1263—either under Alexander or Pope Urban IV—the papacy revoked the grant of the Kingdom of Sicily to Edmund and instead bestowed the title upon Edmund's uncle, Charles I of Anjou.[20][21][22]

Second Barons' War

The barons, led by Edmund's uncle, Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, cited the 'Sicilian business' as one of their grievances against Edmund's father, King Henry III of England.[23][24] This led to Henry's signing of the Provisions of Oxford in 1258, which curtailed his power as well as that of the major barons.[25] However, Edmund collaborated with Henry and his brother Edward to overturn the Provisions in midsummer of 1262.[26] Power in England swung back and forth between Henry and the barons,[27] culminating in the Treaty of Kingston, under which disputes were to be resolved by Edmund's uncles, Richard of Cornwall and King Louis IX of France.[28][29]

Despite the treaty, an open civil war erupted between the royal government and the radical barons led by Simon in the summer of 1263, prompting Edmund to flee from the Tower of London to Dover Castle.[26] On 10 July, Henry wrote to Edmund and Robert de Glaston, the constable of Dover Castle, urging them to surrender the castle to the Bishop of London, Henry of Sandwich, who represented the barons, in preparation for peace negotiations.[26] However, in a letter dated 28 July, Edmund and Robert refused to comply, arguing that surrendering the castle would go against their duties until peace was established. As a result, Henry had to personally command them to relinquish the castle.[26]

When Simon's coalition of barons showed signs of fragmentation,[30] Henry appealed to Louis for arbitration in the dispute, as stipulated in the Treaty of Kingston.[31] Initially resistant to this, Simon eventually agreed to French arbitration, and representatives of Henry and Simon traveled to Paris.[31][32] On 23 January 1264, Louis declared in the Mise of Amiens that Henry had the right to rule over the barons, thereby annulling the Provisions of Oxford. However, the French decision was unpopular; upon Henry's return to England unrest brewed and violence became imminent.[33]

The Second Barons' War finally erupted in April 1264 when Henry's army occupied Simon's territories in the Midlands and advanced to reoccupy a route to France in the southeast.[34] Accompanied by his mother, Eleanor, Edmund went to France, where he helped to raise a mercenary army, with financial assistance from his uncle Louis, to support his father.[35][36] Despite Simon's capture of Henry, Richard and Edward in the Baronial victory at Lewes on 14 May,[37] he failed to consolidate his control over England and Edward managed to escape captivity.[38][39] Following the Baronial defeat at Evesham on 4 August 1265, Simon was killed and dismembered by the royal army, and his lands and title as Earl of Leicester were forfeited.[40]

Earl of Leicester and Lancaster, 1265–1293

Becoming earl

On 26 October 1265, Edmund became the Earl of Leicester when his father, King Henry III of England, granted him the title and associated lands, following the re-creation of the earldom.[21] Additionally, he received all the lands that had belonged to Nicholas Segrave, 1st Baron Segrave, a rebel baron.[41] Once the king's victory over the barons was assured, Edmund returned to England on 30 October 1265.[26] As a political refugee, he harboured a desire for revenge against the barons.[26] Alongside his brother Edward, Edmund focused on suppressing the rebel barons known as the "disinherited," whose lands had been confiscated by the royal government.[26] On 6 December of the same year, Edmund gained control of the castles of Cardigan and Carmarthen, and on 8 January 1266, he acquired the demesnes of Dilwyn, Lugwardine, Marden, Minsterworth and Rodley.[41]

On 28 June of the same year, Edmund acquired the forfeited estates of Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby, whose family had held a significant feudatory since the time of Stephen, King of England.[41] During the Second Barons' War, Robert was seen as an unreliable and violent ally to the barons, as he failed to appear promptly at the Battle of Lewes.[42][43] Moreover, Robert had engaged in indiscriminate raids on lands belonging to his rival, Edward.[42][44] As a result, Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, imprisoned him, fearing his excessive power. After receiving a pardon from Henry, Robert rebelled once again and was captured following his defeat at the Battle of Chesterfield on 15 May of that year.[42] Edmund compelled Robert to agree that he would regain his estates upon payment of an exceedingly hefty sum, fully aware that Robert would be unable to afford such a penalty.[42][44][45] This allowed Edmund to retain control of Robert's estates.[44] When Edward ascended to the throne, he granted Robert's former domain of Chartley Castle to Edmund on 26 July 1276 and absolved Edmund from the debts owed by Robert and his ancestors on 5 May 1277.[42]

During the summer of 1266, Edmund led an army in Warwick to counter the raids carried out by the rebels occupying Kenilworth Castle.[46] The Kenilworth garrison attempted to attack Warwick, but Edmund's forces successfully repelled them back to the castle. Subsequently, the royal army besieged Kenilworth Castle,[46] with Edmund commanding one of the four divisions alongside Henry and Edward.[46][47][48] The siege concluded on 13 December with the implementation of the Dictum of Kenilworth, which brought peace between the king and the baronial forces by 31 October.[46][47][48] Either in the same month or the following year, Edmund acquired Kenilworth Castle.[49][50]

Since Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd of the Welsh Kingdom of Gwynedd was an ally of the barons, Henry dispatched Edmund, along with his Justiciar, Robert Walerand, on a diplomatic mission to negotiate peace with the prince on 21 February 1267.[46] However, Llywelyn refused to make peace with the English until September, when Henry threatened to invade Gwynedd.[46] Edmund continued his diplomatic activities by attending the knighting ceremony of his cousin Philip, conducted by his uncle King Louis IX of France, in Paris on 4 June.[46] During his visit, he received the hospitality of Robert II, Count of Artois and Robert's sister Blanche of Artois.[46][51]

On 30 June 1267, Edmund became the Earl of Lancaster following the title's creation by Henry, and he was granted the royal demesne lands in Lancashire, along with the lordships of Lancaster, Newcastle-under-Lyme and Pickering.[49] Edmund was primarily referred to as this title; the other counties that he controlled, namely Leicester and later Derby, did not It's not clear what it mean for them to "overshadow" in this context. Are you trying to say he was best associated with the title of Lancaster? his association with Lancaster.[52] On the same day, Edward granted Edmund the Three Castles and Monmouth Castle in Wales.[53][54] The following year, Henry appointed Edmund as the Constable of Leicester Castle, a royal possession held in the king's name.[55] The conclusion of the Second Barons' War marked a significant turning point in Edmund's life. Although he had been disappointed by losing the Sicilian crown to his uncle Charles I of Anjou, he had now received a powerful earldom that established the Lancastrian branch of the Plantagenet dynasty.[56] By this time, Edmund had gained a reputation as a ruthless and formidable warrior.[55] With these acquisitions, he became the most influential peer in England.[57] Even upon becoming king, Edward was not worried about Edmund's powerful position or the affairs of most of the baronage because of Edmund's unwavering loyalty to him.[58]

First marriage and crusading

In the Holy Land, under the leadership of the Baibars, the Mamluks captured the city of Antioch, the last remnant of the principality that bears its namesake.[59] The fall of the city led the papal legate of England, Ottobuono—the future Pope Adrian V—to preach for a new crusade.[60] In an elaborate ceremony on 24 June 1268, Edmund pledged himself to undertake a crusade alongside his elder brother Edward and their cousin Henry of Almain.[59][60][61] However, after years of civil war, the English crown had depleted its funds and could not support a crusade.[60][62] Edward was forced to borrow a loan from his uncle, King Louis IX of France,[60][63] who was organizing a large crusader force with the intent of invading Tunis. Despite being in a better position with his newly received earldom, Edmund hastened to marry a wealthy lady to fund the crusade.[60]

On 20 November 1268, King Henry III of England, Edmund's father, arranged a marriage between Edmund and the recently widowed Isabel de Forz, 8th Countess of Devon. Isabel was wealthy countess, holding the earldoms of Devon and Aumale, as well as the lordships of Holderness and the Isle of Wight.[53][60] However, Edmund wanted to ensure the security of his inheritance and decided to marry Isabel's daughter, Aveline de Forz, Countess of Aumale.[64] The marriage between Edmund and Aveline was arranged by Edmund's mother, Eleanor of Provence. On 8 or 9 April 1269, Edmund married 10-year-old Aveline, who was 14 years his junior, in Westminster Abbey;[53][65][66] the marriage could not be consummated until she turned 14.[67] During 1269, Edmund and his brother Edward prepared for the crusade, although they also participated in carrying the remains of Edward the Confessor to Westminster Abbey following the partial completion of the church's reconstruction by Henry on 13 October 1269.[65][68] In addition, Edmund assumed the title of Earl of Derby because Robert de Ferrers, 6th Earl of Derby, was unable to fulfill his obligations. As a result, Edmund merged the title and estates of the Earldom with his Earldoms of Leicester and Lancaster.[42][44][69]

In the summer of 1270, Edmund and Edward were delayed in joining Louis on the crusade because their father was indecisive about participating. Upon the advice of his councilors, Henry chose to remain in England, while Edward led the first group of English crusaders, setting sail from Dover on 20 August that year.[70] The crusaders' plans failed when an epidemic broke out in their camp, killing Louis on 25 August.[59][71] Edward arrived at Tunis on 10 November 1270, but it was too late to engage in battle due to the Treaty of Tunis, which had been signed on 30 October.[72] As a result, most of the crusaders returned home.[72]

Between 25 February and 4 March 1271, Edmund embarked for the Holy Land, leaving his mother Eleanor in charge of his estates.[73] Edward had already set off on a crusade to Palestine to support Bohemund VI of Antioch, and arrived in Acre on 9 May 1271.[74][75] In September 1271, Edmund arrived with a larger army, reinforced by King Hugh III of Cyprus, to assist his brother.[73][76] Despite some successes, such as the raid on Qaqun—where the crusaders reportedly killed one thousand Turkomans—the seizure of numerous cattle[73] and the repulsion of several Mamluk attacks, the limited size of the crusader forces compelled Hugh to sign a 10 year truce with Baibars in May 1272, much to Edward's dismay.[73][76] With the crusade coming to an end, Edmund returned to England around 6 December,[76] where he was greeted by jubilant crowds in London.[77] However, Edmund's crusade proved futile and incurred significant expenses.[77]

Historians Peter Heylyn and Simon Lloyd believe that Edumund received his epithet 'Crouchback' during the crusade, suggesting it as a corruption of 'crossback', as Edmund wore a cross stitched into the back of his garments while on the crusade.[53][78] In 1394, John of Gaunt, the founder of the second House of Lancaster and the husband of Edmund's great-granddaughter Blanche of Lancaster, interpreted the epithet differently, believing that Edmund was a hunchback.[79] According to chronicler John Hardyng, John would forge chronicles to assert that Edmund was the elder brother and not Edward, claiming that the crown passed over him due to his physical deformity.[79] However, Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, presented evidence countering these claims, stating that the chronicles described Edmund as a handsome knight who was skilled in combat.[79]

Second marriage to Blanche of Artois

Edmund's father King Henry III of England died on 16 November 1272, and Edmund's elder brother Edward was proclaimed king.[80] However, Edward was on his way back to England from the Holy Land and his journey was slow, as Edward had to negotiate with King Philip III of France about several claims and put down a Gascon revolt.[77][81][82][83] A rumour spread that Edward was never going to return to England, leading to a growing rebellion in the northern part of the country. Edmund then dispersed the rebels with Roger Mortimer, 1st Baron Mortimer of Wigmore.[84] In 1273, Edmund's wife Aveline turned fourteen and Edmund consummated his marriage with her.[67]

Edward returned to England on 2 August 1274, and he was crowned King Edward I of England on 19 August 1274.[85] Edmund succeeded him as Lord High Steward of England the following day.[86] On 10 November 1274, Aveline suddenly died, leaving Edmund with no children and dashing his hopes to inherit Aveline's titles and earldoms.[53][87] Edmund's maternal aunt and the Queen Dowager of France Margaret of Provence wanted to secure a wealthy bride for her nephew not only for familial reasons,[88] but to convince Edmund's brother Edward to support her claims to Provence against Charles I of Anjou, King of Sicily.[57]

Margaret pushed for the marriage of Edmund and Blanche of Artois, Queen Dowager of Navarre and widow of King Henry I of Navarre, and the Countess of the wealthy and powerful County of Champagne and Brie, which made up more than Edmund's lost possessions.[88][89][90] Blanche accepted the match because she needed a second husband who was congenial to King Philip III of France—who was Edmund's cousin—to help manage Champagne with her.[57] However, the chronicler John of Trokelowe reported that Edmund and Blanche had also known of each others' reputations as a chivalrous knight and a skilled and beautiful regent, respectively, and they became mutually attracted to each other.[88][91][92] Blanche's brother Robert II, Count of Artois, an ally to Charles, was furious upon hearing about their engagement, believing the English to still be hostile to France.[57] Edward, meanwhile, was neutral toward the couple's betrothal, seeing it as nothing more than an additional familial link with his French relatives.[93]

On 6 August 1275, Edmund received a writ of protection to travel overseas from England to France to meet his bride.[51] Between December 1275 and January 1276 in Paris,[51][57] Edmund married Blanche, three years his junior, and thus became a stepfather to Blanche's daughter Joan.[88][89] In the name of Joan, Edmund became the count palatine of Champagne and would govern the County along with his wife until Joan reached the age of majority.[57] That month, Edmund paid homage to Philip III, becoming his vassal.[57][88][94][95] The kings of France struggled in controlling Champagne as a vassal until Joan's betrothal to Philip the Fair, the son of Philip III, which allowed Philip III to fully control the county.[88] Due to his commitments elsewhere, Edmund could only administer Champagne intermittently, with the Grand Butler of France John II of Brienne serving in his absence.[96] In June, Edmund brought Blanche to England to see his English possessions and in July he made a journey to his wife's kingdom of Navarre, around the same time Blanche's brother Robert was pacifying the region.[94][96]

Commander at Wales and diplomat

Following the deterioration of relations between England and the Welsh Kingdom of Gwynedd, Edmund's brother King Edward I of England declared war in November 1276.[97][98] In early 1277, Edmund was summoned to return to England by Edward, along with other English nobles, to proceed against the Prince of Wales, Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.[94] Edmund succeeded Payne de Chaworth as capitaneus of the royal forces in South Wales in April and launched military operations against the Welsh alongside Roger Mortimer and William de Beauchamp, 9th Earl of Warwick.[98] Payne had previously had success in the valley of the River Towy, capturing the castles of Dryslywn, Dinefwr, Carreg Cennan and Llandovery, allowing Edmund, who assumed his command, to push further north, seizing the lands of the Welsh noble Rhys ab Maelgwyn and taking Aberystwyth at the end of July 1277.[99][100] Edmund assigned his troops to rebuild Aberystwyth Castle, then known as Llanbadarn Castle, and returned to England on 20 September, assigning Roger Myles as constable of the castle.[99] The war ended with the Treaty of Aberconwy in November 1277, with Gwynedd surrendering and ceding control over his vassals and conquered territories.[101]

In 1278, Edmund travelled to his dominion of Champagne to administer the county, after which he returned to England to approve and attend the wedding of Llywelyn and his cousin Eleanor de Montfort, the daughter of Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, in Worcester. In the same year, Edmund's wife Blanche gave birth to their son Thomas, who became heir to the Earldom of Lancaster and all of Edmund's domains.[102] The next year, Edward appointed Edmund to be Ambassador to France to negotiate with their cousin King Philip III of France regarding the English claims on the Counties of Agenais and Quercy as part of the dowry of Edmund and Edward's grand-aunt Joan of England, which were under the control of Alphonse, Count of Poitiers.[103]

Since Alphonse died without issue, according to the Treaty of Abbeville of 1259 signed between England and France, the counties as part of Joan's dowry were to be returned to the English crown. Edmund signed a treaty with Philip in May 1279, with Philip renouncing his 1275 oath of allegiance to the vassals of Aquitaine and ceding only Agenais to the English, as he did not believe Quercy to be a part of Joan's dowry.[103] In addition, with the approval of Philip, Edmund started governing the County of Ponthieu alongside his brother-in-law (through his sister Beatrice) Duke John II of Brittany on behalf of his sister-in-law Eleanor of Castile, who inherited the County as Countess following the death of her mother Joan of Dammartin in 1279.[104]

Business in France

In January 1280, a mob formed in Provins, the capital of Brie and also part of the County of Champagne, following the implementation of an unpopular tax, and installed Gilbert de Morry as mayor, killing the previous mayor William Pentecost. Edmund and the Grand Butler of France John II of Brienne marched to Provins with an army, and the leaders of the mob fled, leaving the gates open. Edmund and John forfeited the town's privileges and authorities, disarmed the inhabitants of Provins and condemned the leaders of the mob to death or banishment, with Gilbert being excommunicated. John was more ruthless in punishing the inhabitants of Provins than Edmund; according to a chronicler of the abbey of Saint-Magloire, John ordered hangings, beheadings and mutilations. Edmund went back to visit his estates in England following his chastisement of Provins.[105]

Edmund returned to France and pardoned the town of Provins in July 1281 through the meditation of several church officials and Gilles de Brion, the grand mayor of Donnemarie and brother of Pope Martin IV. Edmund returned privileges to the town, and allowed the inhabitants of Provins to build new fountains, acquire buildings for their courts and establish a bell to mark the work hours and curfew; in exchange, he enacted a harsh tax on the town. The prosperity of Provins soon declined, in contrast to Leicester, a town in Edmund's English domains that saw major growth during his reign.[106] In the same year, Blanche gave birth to Edmund's second son Henry,[107] whose son Henry of Grosmont would eventually become a powerful leader of England during the Hundred Years' War.[108]

In the autumn of 1281, Edmund, as Count Palatine of Champagne, joined forces in Mâcon in October with Philip I of Savoy, Robert II of Burgundy, Otto IV of Burgundy and other nobles to support the claims of his aunt Margaret of Provence to her homeland of Provence against his uncle Charles I of Anjou, who had solidified his control over the region and was unwilling to negotiate.[109] Edmund and the nobles assembled their forces at Lyon in May 1282 to invade Provence, but the eruption of the Sicilian Vespers forced Charles to rent out Provence to Margaret, averting war.[110] That same month, Edmund heard that Wales had launched a war against England, and returned to England to command the English army in South Wales.[111] The Prince of Wales Llywelyn ap Gruffudd retreated southwards when Edward's army pressed hard in North Wales,[112] but a detachment of Edmund's army lured Llywelyn into a trap and killed him in the Battle of Orewin Bridge on 11 December 1282.[111][113] Edward finalized his conquest of Wales through the capture of Llywelyn's brother Dafydd ap Gruffydd in June 1283, who succeeded Llywelyn as Prince of Wales in December.[114]

Ceding Champagne and managing England

As Joan approached the age of 11, the age of majority in France,[115] Edmund debated with his cousin King Philip III of France about whether Joan would still be under his guardianship until she turned 21, in accordance with the laws of Champagne.[116] This would have allowed him to attain management and revenue of the county for a longer duration.[88] For three months, Edmund would query on Joan's age of majority, until Philip III gave a definite assertion and Edmund finally yielded.[88][116]

When Joan reached the age of majority on 14 January 1284, Philip III compromised with Edmund's wife Blanche of Artois on 17 May via a treaty, allowing her to keep several of her dowerlands—the castles of Sézanne, Chantemerle, Nogent-sur-Seine, Pont-sur-Seine and Vertus, and the Palace of Navarrese Kings in Paris—and paying 60 to 70 thousand livres tournois to Edmund and Blanche.[115][116][117] In addition, Philip relinquished any claim to half of the property acquired and held jointly by Blanche and her first husband King Henry I of Navarre in Champagne, and extended this renouncement to Edmund.[116]

Following the marriage of Joan and Prince Philip the Fair, Philip III's son, on 16 August 1284, Edmund renounced the title of Count Palatine of Champagne and ceded control of all of the county except his wife's dowerlands to Philip the Fair.[1][116] Edmund and Blanche's last son, John, was born in May 1286.[118] For the rest of the 1280s, Edmund oversaw the affairs of his lands, such as hiring a chaplain for Tutbury Castle, but also accompanied his brother King Edward I of England when he stayed in Gascony for almost three years.[119][120]

Edward inherited the County of Ponthieu following the death of his wife Eleanor of Castile on 28 November 1290.[121][122] On 23 April 1291, due to Edmund's experience in managing his French domains, Edward granted Ponthieu to Edmund, which he was to administer until Edward's son Edward of Caernarfon gained the age of majority. During the assembly at Norham on 13 June 1291 to select the next King of Scotland, Edmund witnessed the submission of rival claims to the Scottish crown under Edward's arbitration.[121] Edmund also observed the claimants' pledges to accept his brother's decision and witnessed the Scottish nobility swearing fealty to Edward as their overlord.[121]

On 5 February 1292, Edmund was chosen as part of a five-member commission with full authority to establish and enforce regulations to uphold the use of arms in the kingdom.[121] During the same year, he also provided bail for Gilbert de Clare, 7th Earl of Gloucester, when he was involved in a private war with Humphrey de Bohun, 3rd Earl of Hereford, regarding their rights and privileges as Marcher lords.[121] In 1293, Edmund founded the Abbey of the Minoresses of St. Clare without Aldgate, a convent for the Order of Poor Clares, outside Aldgate.[123] Blanche, his wife, facilitated the arrival of the first nuns to the convent from France.[123] Due to the high rank of Edmund and Blanche in society, the Abbey grew more rapidly than any other Minoresses house in England.[124] Edmund also played a role in establishing a Greyfriars priory at Preston, located in his earldom of Lancaster.[125]

Last years, 1293–1296

Crisis with France

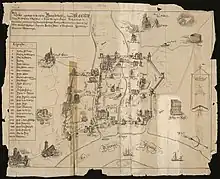

.jpeg.webp)

The cordial relationship between England and France soured intensely when English mariners of the Cinque Ports defeated the Norman fleet off of Brittany in 15 May 1293 and afterwards sacked the port of La Rochelle in Poltiers.[126] Edmund's stepson-in-law and first cousin once removed, King Philip IV of France, was outraged and demanded that Edmund's brother King Edward I of England deliver the offenders and pay for damages, threatening to confiscate the English-held vassal of Gascony and imprison many of its influential citizens.[127] On 27 October 1293, Philip IV formally summoned Edward to come to Paris in person to answer for the charges against him in January 1294.[128][129] The French, especially followers of Philip's brother, Count Charles of Valois, wanted France to annex the Duchy of Aquitaine, which comprises Gascony, believing that Edward wanted war.[128]

Edward did not want war and wanted to show his respect to Philip as his vassal, and sent Edmund and some ambassadors to Paris to negotiate with Philip.[128][129][130] Edmund left England for France between the end of 1293 and the beginning of 1294,[129] bringing his wife Blanche with him.[131] In Paris, Edmund was unsuccessful in negotiating a compromise with Philip, until Philip's wife and Edmund's stepdaughter through Blanche, Queen Joan I of Navarre, and his cousin-in-law Queen Dowager of France Marie of Brabant offered to intervene on Edmund's behalf.[130][131][132] The private conversation between the queens and the English envoys was cordial and easy-going, with the queens assuring Philip.[131]

The English made a secret agreement with Philip: in exchange for Edward's citation being withdrawn, Edward would marry Philip's half-sister Margaret and France would occupy Gascony for 40 days.[131][133] To arrange the marriage, Edward was to come under safe conduct to Amiens in the week before or after Easter of 1294, following the 40 days of occupation.[133] Edmund, satisfied with the agreement, ordered John St John, the Lieutenant of Gascony, to hand Gascony over to the French,[131] but not before receiving a personal assurance from Philip, in front of an audience including the English envoys, Blanche and Duke Robert II of Burgundy, that he would honor his agreement.[133] After hearing rumours of French betrayal and that Margaret would not accept him as a husband, Edward decided not to visit France, much to Philip's anger.[134]

When the 40 days expired, Edmund and the English envoys asked that Gascony be returned to Edward and the citation be withdrawn.[131][134] Philip reassured them that they should not be alarmed, as he planned to give a negative answer in public because he did not want to refuse some of his council members who opposed restoring Gascony to English control.[134][135] The English asked if they could attend the council meeting, but they were refused, and they waited anxiously for Philip's response.[134] Once the meeting was completed, the bishops of Orléans and Tournai told the English envoys that France would keep Gascony and that Philip would not change his mind.[134] Finally, on 21 April, in a parlement session overseen by Philip, Edward was cited again to appear in Paris with no safe conduct granted nor delay allowed.[130][136] Historian Michael Prestwich believes that the French queens were likely acting in good faith in representing Edmund's interests, but that they and Edmund had underestimated their influence on Philip.[130]

War in France

Upon hearing the decision on his brother King Edward I of England, Edmund renounced his homage to King Philip IV of France,[137] and with his wife Blanche of Artois, sold a part of her dowerlands to an abbey.[134] The couple returned to England with all of their English household and John of Brittany, who had also renounced his homage to Philip.[137] Edward formally renounced his homage to Philip and the English baronage prepared for war.[137] On 1 July 1294, Edward wrote to his administrators in Gascony, apologizing for the secret treaty and stating that he would send Edmund and the Earl of Lincoln Henry de Lacy to reclaim Gascony. On 3 September, he ordered the Cinque Ports to provide shipping for Edmund's voyage.[137][138] Following the suppression of a Welsh rebellion, Edmund and his envoys explained the causes of the war to a council of magnates on 5 August 1295.[138][139] Edmund was among the loudest of the nobles in their cries for war.[139]

Edmund planned to launch his expedition to Gascony in October, but fell ill that autumn and did not depart England until the winter.[140] With his expedition, he brought his wife Blanche, Earl Henry de Lacy, 26 knights bannerets and 1,700 men-at-arms.[138][140][141] The English prince landed in Pointe Saint-Mathieu in Brittany, sending messengers that they would rest there for several days.[142] The Bretons responded by hanging the messengers, resulting in Edmund's forces looting the countryside.[142] English soldiers also looted the Abbey of Saint-Mathieu de Fine-Terre, although Edmund ordered them to return all stolen valuables.[142] The English army then arrived at Brest, where they received supplies, and sailed down to Blaye and later Castillon, where they landed their forces.[142]

The castle of Lesparre surrendered to Edmund's forces on 22 March 1296 and Edmund launched his siege of Bordeaux with his encampment in Bègles in the south.[143] On 28 March, the Bordeaux garrison attempted to surprise the English encampment, but realized that the English were waiting for them and hastily retreated back to the city, sustaining many casualties.[143] On 30 March, the English broke into the outer wall of Bordeaux, but did not have siege engines to break through the city's inner walls.[144] Hearing that his brother-in-law Robert II, Count of Artois, was in command of a French army at Langon, Edmund and his army left Bordeaux to meet him.[144] Edmund did not find his brother-in-law there and the village there surrendered to him.[144] Edmund then launched a siege of the castle in nearby Saint-Macaire, alerting Robert to send his forces to relieve the castle. Realizing his funds were low, Edmund returned to Bordeaux to siege the city.[144]

Death and burial

During the siege of Bourdeaux, Edmund ran out of money to pay his army and his mercenaries deserted him.[145] Edmund and his remaining forces then travelled to Bayonne, where he was warmly received, although the failure of his campaign troubled him.[145] The English prince fell sick on 13 May 1296 and died on 5 June.[138][145] In his will, Edmund instructed that his body should not be buried until his debts were paid.[145] Edmund's remains were embalmed and initially kept at the church of the Friars Minors in Bayonne.[145] After six months, they were transferred to the Convent of the Minoresses in London.[145] On 17 November 1296, Edmund's widow, Blanche of Artois, obtained safe conduct for her return to England.[145] In 1298, she received a third of Edmund's estates as part of her dowry.[145] On 24 March 1301, Edmund's body was transported to St Paul's Cathedral and later moved to Westminster Abbey, where it was laid to rest in an elaborate tomb near the resting place of Edmund's first wife, Aveline de Forz.[145][146]

Family

Issue

Edmund's first wife Aveline de Forz died before the couple could have any children.[87]

By his second wife Blanche of Artois, Edmund had four children. Of these, all three of his sons outlived their father. Edmund's children with Blanche were:[89][148][79]

- Thomas (b. c. 1278 – 22 March 1322)[118]

- Henry (b. c. 1281 – 22 September 1345)[118]

- John (b. bef. May 1286 – 13 June 1317)[118]

- Mary, no dates were recorded, presumably died young in France[118]

Through his marriage to Blanche, Edmund also became stepfather to Queen Joan I of Navarre.[88][89]

Ancestry and family tree

| Ancestors of Edmund Crouchback |

|---|

| Family tree of the Dukes of: Beaufort, Lancaster, and Somerset, Marquesses of: Dorset, Hertford, Somerset and Worcester, and Earls of: Dorset, Hertford, Lancaster, Leicester, Somerset, and Worcester | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Chisholm 1911, p. 948–949.

- Howell 2001, pp. 44–45

- Rhodes 1895, p. 20.

- Howell 1992, p. 57; Howell 2001, p. 27.

- Howell 2001, pp. 32, 102; Cole 2002, p. 230

- Weiler 2012, pp. 149, 161

- Weiler 2012, pp. 122, 147

- Weiler 2012, pp. 147–149

- Weiler 2012, p. 151

- Weiler 2012, pp. 149, 152; Carpenter 2004, p. 347

- Rhodes 1895, p. 27.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 102.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 25.

- Weiler 2012, p. 152; Jobson 2012, p. 13

- Weiler 2012, p. 152; Jobson 2012, p. 13

- Weiler 2012, p. 158

- Weiler 2012, pp. 155–156; Jobson 2012, p. 13

- Jobson 2012, p. 13

- Jobson 2012, p. 13; Carpenter 2004, p. 347

- Runciman 1958, p. 59–63.

- Baines 1868, p. 32.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 103.

- Hillaby & Hillaby 2013, pp. 52–53

- Howell 2001, pp. 152–153; Carpenter 2004, p. 347

- Howell 2001, p. 156; Jobson 2012, pp. 22, 25

- Rhodes 1895, p. 28.

- Carpenter 2004, pp. 372–377

- Jobson 2012, p. 73

- Jobson 2012, pp. 73–74

- Jobson 2012, p. 100

- Jobson 2012, pp. 100–103

- Jobson 2012, p. 103

- Jobson 2012, pp. 13–105; Hallam & Everard 2001, p. 283

- Jobson 2012, pp. 109–112

- Jobson 2012, pp. 120–121

- Powicke 1962, p. 280.

- Jobson 2012, pp. 115, 117

- Jobson 2012, pp. 119–120

- Jobson 2012, pp. 136–137

- Jobson 2012, pp. 140–146

- Rhodes 1895, p. 31.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 31-32.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 388.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 360.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 169.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 29.

- Conduit 2004, p. 12–13.

- Tout 1905, p. 131.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 32.

- Sharpe 1825, p. 12.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 214.

- Trokelowe & Blaneforde 1866, p. 70.

- Lloyd 2004.

- Knight 2009, p. 12; Taylor 1961, p. 174

- Rothero 1984, p. 32.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 29-30.

- Powicke 1962, p. 239.

- Powicke 1962, p. 518.

- Lower 2018, p. 76.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 209.

- Morris 2009, pp. 83.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 71.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 72.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 209-210.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 210.

- Spencer 2014, p. 14.

- Blank 2007, p. 150.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 122.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 121.

- Lower 2018, p. 174–76.

- Lower 2018, p. 104.

- Lower 2018, p. 134–35.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 211.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 75.

- Lower 2018, p. 179–182.

- Baldwin 2014, p. 43.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 212.

- Heylin 1652, p. 110.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 235.

- Prestwich 1997, pp. 78, 82.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 82.

- Carpenter 2004, p. 466.

- Hamilton 2010, pp. 56–57.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 212-213.

- Hamilton 2010, p. 58.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 213.

- Weir 2008, p. 76.

- Woodacre 2013, p. 33.

- Richardson 2011, p. 103.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 213-216.

- Trokelowe & Blaneforde 1866, p. 70-71.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 213, 236.

- Powicke 1962, p. 239–240.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 217.

- Powicke 1962, p. 236.

- Powicke 1962, p. 240.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 170.

- Powicke 1962, p. 409.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 217-218.

- Powicke 1962, p. 410.

- Powicke 1962, p. 413.

- Maddicott 2008.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 219-220.

- Powicke 1962, p. 235.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 221-222.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 222-223.

- Armitage-Smith 1904, p. 197.

- Ormrod 2004.

- Powicke 1962, p. 248.

- Powicke 1962, p. 248–249.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 218.

- Prestwich 2007, p. 155

- Davies 2000, p. 353

- Carpenter 2003, p. 510

- Powicke 1962, p. 240-241.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 224-225.

- Woodacre 2013, p. 35.

- Weir 2008, p. 83–88.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 225.

- Morris 2009, pp. 204–217.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 226.

- Morris 2009, p. 229.

- Page 1909, p. 516–519.

- Ward 1992, p. 155.

- Farrer & Brownbill 1908, p. 162.

- Powicke 1962, p. 644.

- Powicke 1962, p. 645.

- Powicke 1962, p. 646.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 227.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 299.

- Powicke 1962, p. 647.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 227-228.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 228.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 229.

- Powicke 1962, p. 647-648.

- Powicke 1962, p. 648.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 230.

- Powicke 1962, p. 649.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 230-231.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 231.

- Baines 1868, p. 123.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 231-232.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 232.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 233.

- Rhodes 1895, p. 234.

- Prestwich 1997, p. 45.

- Pinches & Pinches 1974, p. 32.

- Craig 2006, p. 160.

Bibliography

- Armitage-Smith, Sir Sydney (1904). John of Gaunt: king of Castile and Leon, duke of Aquitaine and Lancaster. Archibald Constable and Co. Ltd.

- Baines, Edward (1868). The History of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancaster. G. Routledge and Sons. Retrieved 20 July 2023 – via Google Books.

- Baldwin, Philip (2014). Pope Gregory X and the Crusades. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843839163.

- Blank, Hanne (2007). Virgin: The Untouched History. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1596910119. OL 8892202M.

- Carpenter, David A. (2003). The Struggle for Mastery: Britain, 1066–1284. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-522000-5.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). pp. 948–949.

- Cole, Virginia A. (2002). "Ritual Charity and Royal Children in 13th Century England". In Rollo-Koster, Joëlle (ed.). Medieval and Early Modern Ritual: Formalized Behavior in Europe, China and Japan. Leiden, the Netherlands: BRILL. pp. 221–241. ISBN 978-90-04-11749-5.

- Conduit, Brian (2004). Battlefield Walks in the Midlands. Sigma Leisure. ISBN 978-1-85058-808-5.

- Craig, Taylor (2006). Debating the Hundred Years War. Vol. 29: Pour Ce Que Plusieurs (La Loy Salicque) And a Declaration of the Trew and Dewe Title of Henry VIII. Cambridge University Press. OL 17229524M.

- Davies, R. R. (2000). The Age of Conquest: Wales, 1063–1415. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820878-2. OL 3752492W.

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, J, eds. (1908). "Friaries: Franciscan friars, Preston". A History of the County of Lancaster. 2: 162. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 3 July 2023 – via British History Online.

- Hallam, Elizabeth M.; Everard, Judith A. (2001). Capetian France, 987–1328 (2nd ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40428-1. OL 5117242W.

- Hamilton, J.S. (2010). The Plantagenets: History of a Dynasty. Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-5712-6. OL 28013041M.

- Heylin, Peter (1652). Cosmographie. p. 110. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- Howell, Margaret (1992). "The Children of King Henry III and Eleanor of Provence". In Coss, Peter R.; Lloyd, Simon D. (eds.). Thirteenth Century England: Proceedings of the Newcastle upon Tyne Conference, 1991. Vol. 4. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 57–72. ISBN 0-85115-325-9.

- Hillaby, Joe; Hillaby, Caroline (2013). The Palgrave Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23027-816-5.

- Hilton, Lisa (2010). Queens Consort: England's Medieval Queens from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Elizabeth of York. Pegasus Classics. ISBN 978-1605981055.

- Howell, Margaret (2001). Eleanor of Provence: Queenship in Thirteenth-Century England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-631-22739-7.

- Jobson, Adrian (2012). The First English Revolution: Simon de Montfort, Henry III and the Barons' War. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-84725-226-5.

- Knight, Jeremy K. (2009) [1991]. The Three Castles: Grosmont Castle, Skenfrith Castle, White Castle (revised ed.). Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-266-1.

- Lloyd, Simon (2004). "Edmund, first earl of Lancaster and first earl of Leicester (1245–1296)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8504. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lower, Michael (2018). The Tunis Crusade of 1270: A Mediterranean History (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198744320.

- Maddicott, J. R. (2008). "Thomas of Lancaster, second earl of Lancaster". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online) (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27195. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Morris, Marc (2009). A Great and Terrible King: Edward I and the Forging of Britain. London: Windmill Books. ISBN 978-0-0994-8175-1. OL 22563815M.

- Ormrod, W. M. (2004). "Henry of Lancaster [Henry of Grosmont], first duke of Lancaster (c. 1310–1361), soldier and diplomat". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12960. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Page, William, ed. (1909). "Friaries: The minoresses without Aldgate". A History of the County of London: Volume 1, London Within the Bars, Westminster and Southwark. London: Victoria County History. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023.

- Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974). The Royal Heraldry of England. Heraldry Today. Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press. ISBN 0-900455-25-X.

- Powicke, F. M. (Frederick Maurice) (1962). The Thirteenth Century, 1216–1307 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 3693188. OL 10470039W.

- Prestwich, Michael (1997). Edward I. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300071573. OL 20208104M.

- —— (2007). Plantagenet England: 1225–1360 (new ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822844-8. OL 2757010W.

- Rhodes, Walter E. (1895). "Edmund, Earl of Lancaster". The English Historical Review. 10 (37): 19–40, 209–237. JSTOR 547990. Archived from the original on 3 July 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023 – via JSTOR.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Rothero, Christopher (1984). The Scottish and Welsh Wars 1250–1400. Osprey Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 9780850455427.

- Runciman, Steven (1958). The Sicilian Vespers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–63. ISBN 9780521437745.

- Richardson, Douglas (2011). Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study In Colonial And Medieval Families. Douglas Richardson. ISBN 978-1-4610-4513-7. OL 37774237M.

- Sharpe, Henry (1825). Concise History and Description of Kenilworth Castle: From its Foundation to the Present Time (16th ed.). Warwick: Sharpe. OCLC 54148330.

- Spencer, Andrew (2014). Nobility and Kingship in Medieval England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107026759.

- Taylor, A. J. (1961). "White Castle in the Thirteenth Century: A Re-Consideration". Medieval Archaeology. 5: 169–175. doi:10.1080/00766097.1961.11735651.

- Tout, Thomas Frederick (1905). The History of England from the Accession of Henry III. to the Death of Edward III. (1216–1377). Longmans, Green and Co.

- Trokelowe, John de; Blaneforde, Henry (1866). Riley, Henry Thomas (ed.). Chronica et annales, regnantibus Henrico Tertio, Edwardo Primo, Edwardo Secundo, Ricardo Secundo, et Henrico Quarto. London: Longmans, Green, Reader & Dyer. pp. 70–71. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2023 – via Google Books.

- Weiler, Björn K. U. (2012). Henry III of England and the Staufen Empire, 1216–1272. Paris: Royal Historical Society: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-86193-319-8.

- Ward, Jennifer C. (1992). English Noblewomen in the Later Middle Ages (The Medieval World) (1st ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0582059658. OL 1564675M.

- Weir, Alison (2008). Britain's Royal Families, The Complete Genealogy. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0099539735. OL 497239W.

- Woodacre, Elena (2013). The Queens Regnant of Navarre: Succession, Politics, and Partnership, 1274–1512. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-33915-7.