Effects of Hurricane Harvey in Texas

Hurricane Harvey caused major flooding in southern Texas for four days in August 2017. Hurricane Harvey formed on August 17, 2017 in the open Atlantic. Six days later, after degenerating back into a tropical wave and moving through the Caribbean Sea, Harvey reformed and rapidly intensified in the Gulf of Mexico. Early on August 26, Harvey made landfall in San José Island, Texas at peak intensity as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 130 mph and a pressure of 937 mb. A couple of hours Harvey made another landfall in Holiday Beach as a slightly weaker high-end Category 3 storm. After that, Harvey rapidly weakened and stalled for multiple days over Texas, dropping torrential rainfall. Harvey eventually moved back into the Gulf on August 28, and a day later, Harvey made a fifth and final landfall west of Cameron, Louisiana.

Hurricane Harvey at peak intensity, shortly before making landfall in Rockport, Texas | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Duration | August 25–31, 2017 |

| Category 4 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 937 mbar (hPa); 27.67 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 68 direct, 35 indirect |

| Damage | $51.2 billion (2017 USD) to $125 billion (2017 USD) |

| Areas affected | Texas |

Part of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season | |

| History • Meteorological history Effects • Commons: Harvey images | |

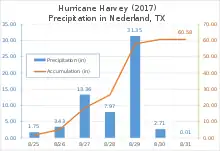

The large and powerful hurricane dropped heavy rainfall over parts of southern and southeastern Texas. Over four days, Harvey dropped large amounts of rainfall, peaking at 60.58 inches (1,539 mm) in Nederland, Texas, making it the wettest tropical cyclone on record in the United States.[1] The highest gust from Harvey was recorded at 140 mph (230 km/h) in Rockport, Texas, where every single building was damaged by the storm. Overall, Harvey contributed to 68 direct deaths and 35 indirect deaths–a total of 103–and caused at least $51.177 billion in damage in Texas alone.[2][3]

Background

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

A tropical wave developed into a tropical storm on August 17, receiving the name Harvey.[4] It passed through the Lesser Antilles into Eastern Caribbean, where wind shear weakened the system, causing it to degenerated back into a tropical wave late on August 19.[4] The wave continued generally westward through Caribbean Sea before turning northwestward and beginning to reorganize as it moved over the Yucatan Peninsula into the Gulf of Mexico. At 12:00 UTC on August 26, it redeveloped into a tropical depression, before restrengthening into a tropical storm six hours later. Harvey then began to rapidly intensify as it moved northwestward toward the Texas Gulf Coast. After becoming a hurricane on August 24, Harvey continued to quickly strengthen over the next day, ultimately reaching peak intensity as a Category 4 hurricane. Around 03:00 UTC on August 26, the hurricane made landfall at peak intensity on San Jose Island, just east of Rockport, with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) and an atmospheric pressure of 937 mbar (27.7 inHg), becoming the first major hurricane to make landfall in the United States since Wilma in 2005.[4] Weakening began as the eye of Harvey moved further inland, and Harvey made a subsequent landfall on the northeastern shore of Copano Bay at 06:00 UTC with slightly lower winds of 125 mph (201 km/h).[5][4] Harvey then rapidly weakened as its forward speed slowed dramatically to a crawl, and Harvey weakened to a tropical storm on August 26. For about two days the storm stalled just inland, dropping very heavy rainfall and causing widespread flash flooding. Around Houston, a city of 2.3 million people, average rainfall amounts were around 2 feet (0.61 m).[6] Harvey's center eventually drifted back towards the southeast and ultimately reemerged into the Gulf on August 28. Deep convection persisted north of the cyclone's center near the Houston metropolitan area along a stationary front, resulting in several days of record-breaking rain. Early on August 30, the former hurricane made its fifth and final landfall just west of Cameron, Louisiana with winds of 45 mph (72 km/h).[4]

Preparations

Upon the NHC resuming advisories for Harvey at 15:00 UTC on August 23, a hurricane watch was issued in Texas from Port Mansfield to San Luis Pass, while a tropical storm watch was posted from Port Mansfield south to the mouth of the Rio Grande and from San Luis Pass to High Island. Additionally, a storm surge watch became in effect from Port Mansfield to High Island. Additional watches and warnings were posted in these areas at 09:00 UTC on August 24, with a hurricane warning from Port Mansfield to Matagorda; a tropical storm warning from Matagorda to High Island; a hurricane watch and tropical storm warning from Port Mansfield to the Rio Grande; a storm surge warning from Port Mansfield to San Luis Pass; and a storm surge watch from Port Mansfield to the Rio Grande.[4] As the hurricane neared landfall on August 24, an extreme wind warning—indicating an immediate threat of 115–145 mph (185–233 km/h) winds—was issued for areas expected to be impacted by the eyewall; this included parts of Aransas, Calhoun, Nueces, Refugio, and San Patricio counties.[7] The watches and warnings were adjusted accordingly after Harvey moved inland and began weakening, with the warning discontinued at 15:00 UTC on August 26. By 09:00 UTC on the following day, only a tropical storm warning and a storm surge warning remained in effect from Port O'Connor to Sargent. However, watches and warnings were re-issued as Harvey began to re-emerge into the Gulf of Mexico, and beginning at 15:00 UTC on August 28, a tropical storm warning was in effect for the entire Gulf Coast of Texas from High Island northward.[4]

Governor Greg Abbott declared a state of emergency for 30 counties on August 23, while mandatory evacuations were issued for Brazoria, Calhoun, Jackson, Refugio, San Patricio, and Victoria counties, as well as parts of Matagorda County.[8] On August 26, Governor Abbott added an additional 20 counties to the state of emergency declaration.[9] Furthermore, the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters was activated by the USGS on behalf of the Governor's Texas Emergency Management Council, including the Texas Division of Emergency Management, thus providing for humanitarian satellite coverage.[10] The Padre Island National Seashore also closed on August 24.[11]

Impacts

_(50).jpg.webp)

22 weak tornadoes touched down throughout the state. An EF1 tornado near Fresno caused some minor injuries. Total damage from the tornadoes reached $7.601 million, according to the National Centers for Environmental Information.[12]

Throughout Texas, approximately 336,000 people were left without electricity and tens of thousands required rescue. Throughout the state, 103 people died in storm-related incidents: 68 from its direct effects, including flooding, and 35 from indirect effects in the hurricane's aftermath.[4] By August 29, 2017 approximately 13,000 people had been rescued across the state while an estimated 30,000 were displaced.[13] The refinery industry capacity was reduced, and oil and gas production was affected in the Gulf of Mexico and inland Texas.[14][15] On Monday, the closure of oil refineries ahead of Hurricane Harvey created a fuel shortage. Panicked motorists waited in long lines. Consequently, gas stations through the state were forced to close due to the rush.[16] More than 20 percent of refining capacity was affected.[17]

.jpg.webp)

More than 48,700 homes were affected by Harvey throughout the state, including over 1,000 that were completely destroyed and more than 17,000 that sustained major damage; approximately 32,000 sustained minor damage. Nearly 700 businesses were damaged as well.[18] Yet the Texas Department of Public Safety stated more than 185,000 homes were damaged and 9,000 destroyed.[19] Over 500 roads closed throughout Texas, leading to the Texas Department of Transportation website receiving 5 million visits.[20]

The hurricane also caused many people to believe that in the wild, only 10 individuals of Attwater's prairie chicken remained at most[21] until Spring 2018, when it was discovered that there were about a dozen wild individuals left.[22]

Landfall area

Making landfall as a Category 4 hurricane, Harvey inflicted tremendous damage across Aransas County.[23] Wind gusts were observed up to 132 mph (212 km/h) near Port Aransas.[24] Nearly every structure in Port Aransas was damaged, some severely, while significant damage from storm surge also occurred.[23] In Rockport, entire blocks were destroyed by the hurricane's violent eyewall winds. The city's courthouse was severely damaged when a cargo trailer was hurled into it, coming to a stop halfway through the structure. The gymnasium of the Rockport-Fulton High School lost multiple walls while the school itself suffered considerable damage.[23] Many homes, apartment buildings, and businesses sustained major structural damage from the intense winds, and several were completely destroyed. Numerous boats were damaged or sunk at a marina in town, airplanes and structures were destroyed at the Aransas County Airport, and a Fairfield Inn in the city was severely damaged as well.[25] About 20 percent of Rockport's population was displaced, and they were still unable to return to their homes a year after the hurricane.[26] One person died in a house fire in the city, unable to be rescued due to the extreme weather conditions.[27] Just north of Rockport, many structures were also severely damaged in the nearby town of Fulton. In the small community of Holiday Beach, catastrophic damage occurred as almost every home in town was severely damaged or destroyed by storm surge and violent winds. By the afternoon of August 26, more than 20 in (510 mm) of rain had fallen in the Corpus Christi metropolitan area.[9] All of Victoria was left without water and most had no power.[23]

Houston metropolitan area flooding

Many locations in the Houston metropolitan area observed at least 30 in (760 mm) of precipitation,[28] with a maximum of 60.58 in (1,539 mm) in Nederland.[29] This makes Harvey the wettest tropical cyclone on record for both Texas and the United States,[30] surpassing the previous rainfall record held by Tropical Storm Amelia.[31] The local National Weather Service office in Houston observed all-time record daily rainfall accumulations on both August 26 and 27, measured at 14.4 and 16.08 in (366 and 408 mm) respectively.[32] Due to the amount of rain accumulated from Harvey, the National Weather Service added 2 new colors to the rain index representing around 50% of the maximum rainfall dropped by Harvey. Multiple flash flood emergencies were issued in the Houston area by the National Weather Service beginning the night of August 26. In Pearland, a suburb south of Houston, a report was made of 9.92 in (252 mm) of rainfall in 90 minutes.[33] The 39.11 in (993 mm) of rain in August made the month the wettest ever recorded in Houston since record keeping began in 1892, more than doubling the previous record of 19.21 in (488 mm) in June 2001.[34] The 32.47 inches (825 mm) of rain from August 26-28 set a United States record for highest 3 day rainfall at a major city.[35] The storm surge peaked at 6 feet at Port Lavaca,[36][37] reducing outflow of rainwater from land to sea.[38]

During the storm, more than 800 Houston area flights were canceled, including 704 at George Bush Intercontinental Airport and 123 at William P. Hobby Airport. Both airports eventually closed.[39] Several tornadoes were spawned in the area, one of which damaged or destroyed the roofs of dozens of homes in Sienna Plantation.[9] As of August 29, 14 fatalities have been confirmed from flooding in the Houston area, including 6 from the same family who died when their van was swept off a flooded bridge.[40] A police officer drowned while trying to escape rising waters.[41]

An estimated 25–30 percent of Harris County—roughly 444 sq mi (1,150 km2) of land—was submerged.[13]

Late on August 27, a mandatory evacuation was issued for all of Bay City as model projections indicated the downtown area would be inundated by 10 ft (3.0 m) of water. Flooding was anticipated to cut off access to the city around 1:00 p.m. CDT on August 28.[42] Evacuations took place in Conroe on August 28 following release of water from the Lake Conroe dam.[43] On the morning on August 29, a levee along Columbia Lakes in Brazoria County was breached, prompting officials to urgently request for everyone in the area to evacuate.[44][45]

On August 28, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began controlled water releases from Addicks and Barker Reservoirs in the Buffalo Bayou watershed in an attempt to manage flood levels in the immediate area. According to the local Corps commander, "It's going to be better to release the water through the gates directly into Buffalo Bayou as opposed to letting it go around the end and through additional neighborhoods and ultimately into the bayou." At the time the releases started, the reservoirs had been rising at more than 6 inches (150 mm) per hour.[46] Many people began evacuating the area, fearing a levee breach.[47] Despite attempts to alleviate the water rise, the Addicks Reservoir reached capacity on the morning of August 29 and began spilling out.[48] The NASA Johnson Space Center was closed to employees and visitors due to the flooding until September 5. Only the critical mission control staff remained and resided in the control rooms to monitor procedures of the International Space Station.[49]

Deep East Texas and Beaumont to Port Arthur area

Anyone who chooses to not [evacuate] cannot expect to be rescued and should write their social security numbers in permanent marker on their arm so their bodies can be identified. The loss of life and property is certain. GET OUT OR DIE!

— Jacques Blanchette, Tyler County Emergency Management[50]

The Beaumont–Port Arthur metropolitan area also experienced torrential precipitation, including 32.55 in (827 mm) of rainfall in Beaumont.[28] Rising waters of the Neches River caused the city to lose service from its main pump station, as well as its secondary water source in Hardin County, cutting water supply to the city for an unknown amount of time.[51] Flooding to the north and east of the Houston area resulted in mandatory evacuations for portions of Liberty, Jefferson, and Tyler counties, while Jasper and Newton counties were under a voluntary evacuation.[52] One death occurred in Beaumont when a woman exited her disabled vehicle, but was swept away.[53] In Port Arthur, the mayor stated that the entire city was submerged by water. Hundreds of displaced residents went to the Robert A. "Bob" Bowers Civic Center for shelter, but they were evacuated again after the building began to flood. Water entered at least several hundreds of homes in Jefferson County.[54]

Energy production

Energy production in the Gulf of Mexico declined in the wake of Harvey by approximately 21% — the output dropped to 378,633 barrels per day from the original 1.75 million barrels of oil produced each day. The Eagle Ford Rock Formation (shale oil and gas) in southern Texas reduced production by 300,000 to 500,000 barrels per day (bpd), according to the Texas Railroad Commission. Many energy-related ports and terminals closed, delaying about fourteen crude oil tankers. About 2.25 million bpd of refining capacity was offline for several days; that is about 12% of total US capacity, with refineries affected at Corpus Christi, and later Port Arthur and Beaumont, and Lake Charles, Louisiana. The price of Brent crude versus West Texas Intermediate crude oil achieved a split of U.S. $5.[55]

Two ExxonMobil refineries had to be shut down following related storm damage and releases of hazardous pollutants.[56] Two oil storage tanks owned by Burlington Resources Oil and Gas collectively spilled 30,000 US gallons (110,000 L) of crude in DeWitt County. An additional 8,500 US gallons (32,000 L) of wastewater was spilled in the incidents.[57]

On August 30, the CEO of Arkema warned one of its chemical plants in Crosby, Texas, could explode or be subject to intense fire due to the loss of "critical refrigeration" of materials.[58] All workers at the facility and residents within 1.5 mi (2.4 km) were evacuated. Eight of the plant's nine refrigeration units failed without power, enabling the stored chemicals to decompose and become combustible. Two explosions occurred around 2:00 a.m. on August 31; 21 emergency personnel were briefly hospitalized.[59]

Due to the shutdown in refineries, gas prices did see an increase nationwide.[60] However, the increase was not as extensive as Hurricane Katrina.[61] Additionally, Harvey's impact coincided with Labor Day Weekend, which sees a traditional increase in gas prices due to the heavy travel for that weekend.[62] Nonetheless, the spike brought the highest gas prices in two years.[61]

Sports

The flooding in Houston from the storm required the traditional Governor's Cup National Football League preseason game between the Dallas Cowboys and the Houston Texans scheduled for August 31 to be moved from NRG Stadium in Houston to AT&T Stadium in Arlington, Texas.[63] The game was later cancelled to allow the Houston Texans players to return to Houston after the storm.[64] In addition, the Houston Astros were forced to move their August 29–31 series with the Texas Rangers from Minute Maid Park in Houston to Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg, Florida;[65] ironically, just two weeks later, Hurricane Irma would force the stadium's regular tenants, the Tampa Bay Rays, to move three home games to Citi Field in New York City.[66] This was despite a protectable roof at Minute Maid Park.[67] In the aftermath, the Houston Astros began to wear patches which had the logo of the team with the word "Strong" on the bottom of the patch, as well as promoting the hashtag Houston Strong, prominently displaying them as the Astros won the 2017 World Series.[68][69] Manager A. J. Hinch has stated in an interview that the team wasn't just playing for a title, but to help boost moral support for the city.[70] The annual Texas Kickoff game that was to feature BYU and LSU to kick off the 2017 college football season was moved to the Mercedes-Benz Superdome in New Orleans, Louisiana.[71] The NCAA FBS football game between Houston and UTSA was postponed due to the aftermath of the storm. It was originally scheduled for September 2 at the Alamodome in San Antonio and was ultimately canceled.[72]

The Houston Dynamo rescheduled a planned Major League Soccer match against Sporting Kansas City on August 26 to October 11. The Houston Dash of the National Women's Soccer League rescheduled their August 27 match against the North Carolina Courage to a later date.[73] Both teams moved their training camps to Toyota Stadium in Frisco, Texas (near Dallas) while preparing for their next matches; the Dash's match the following week, against the Seattle Reign, was played in Frisco, with all proceeds from ticket sales benefiting an American Red Cross relief fund for hurricane victims.[74] The Dynamo and Major League Soccer also donated a combined $1 million into the hurricane relief fund, while also opening BBVA Compass Stadium to accept donated supplies for processing and distribution.[75][76]

Aftermath

_170828-Z-FG822-026_(36127995543).jpg.webp)

Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner imposed a mandatory curfew on August 29 from midnight to 5 a.m. local time until further notice. He cited looting as the primary reason for the curfew.[77] On August 29, U. S. President Donald Trump, First Lady Melania Trump, and U.S. Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz toured damage in the Corpus Christi metropolitan area.[78] Trump made a formal request for $5.95 billion in federal funding on August 31 for affected areas, the vast majority of which would go to FEMA.[79]

Texas Governor Greg Abbott deployed the state's entire National Guard for search and rescue, recovery, and clean up operations due to the devastating damage caused by the storm and resulting floods.[80][81] Other states' National Guard's have offered assistance, with several having already been sent.[82][83] Texas Civil Air Patrol units were activated to assist in search and rescue and damage assessment. Meanwhile, the United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement assigned approximately 150 employees from around the country to assist with disaster relief efforts, while stating that no immigration enforcement operations would be conducted.[18]

Approximately 32,000 people were displaced in shelters across the state by August 31. The George R. Brown Convention Center, the state's largest shelter, reached capacity with 8,000 evacuees. The NRG Center opened as a large public shelter accordingly. More than 210,000 people registered with FEMA for disaster assistance.[84]

The Cajun Navy, an informal organization of volunteers with boats from Louisiana, deployed to Texas to assist in high-water rescues.[85]

The Houston Independent School District announced that all students on any of the district's campuses would be eligible for free lunch throughout the 2017–18 school year. The Federal Department of Education eased financial aid rules and procedures for those affected by Harvey, giving schools the ability to waive paperwork requirements; loan borrowers were given more flexibility in managing their loan payments.[18] A 36-year-old inmate sentenced to death for a 2003 murder was granted a temporary reprieve as a result of Harvey, as his legal team was based in Harris County, an area heavily affected by the hurricane.[18]

By August 30, corporations across the nation collectively donated more than $72 million to relief efforts, with 42 companies donating at least $1 million.[86] Professional athletic teams, their players, and managers provided large donations to assist victims of the storm. The Houston Astros pledged $4 million to relief along with all proceeds from their home game raffles. Houston Rockets owner Leslie Alexander also donated $4 million to the cause.[87] A fundraiser established by Houston Texans defensive lineman J. J. Watt exceeded $37 million. For his efforts, Watt received the Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year Award.[88] The Texas Rangers and Tennessee Titans both provided $1 million, while the New England Patriots pledged to match up to $1 million in donations to the Red Cross.[89] Multiple Hollywood celebrities also pitched in, collectively donating more than $10 million, with Sandra Bullock providing the largest single donation of $1 million.[90] Leonardo DiCaprio provided $1 million to the United Way Harvey Recovery Fund through his foundation.[91] Trump donated $1 million to 12 charities involved in relief efforts.[92] Rachael Ray provided donations totaling $1 million to animal shelters across the Houston area.[93]

Economic loss estimates

| Rank | Hurricane | Season | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 Katrina | 2005 | $125 billion |

| 4 Harvey | 2017 | ||

| 3 | 4 Ian | 2022 | $113 billion |

| 4 | 4 Maria | 2017 | $90 billion |

| 5 | 4 Ida | 2021 | $75 billion |

| 6 | ET Sandy | 2012 | $65 billion |

| 7 | 4 Irma | 2017 | $52.1 billion |

| 8 | 2 Ike | 2008 | $30 billion |

| 9 | 5 Andrew | 1992 | $27 billion |

| 10 | 5 Michael | 2018 | $25 billion |

Moody's Analytics initially estimated the total economic cost of the storm at $81 billion to $108 billion or more; most of the economic losses are damage to homes and commercial property.[96] Reinsurance company Aon Benfield estimated total economic losses at $100 billion, including $30 billion in insured damage, making Harvey the costliest disaster in 2017 by their calculations.[97] USA Today reported an AccuWeather estimate of $190 billion, released August 31.[98] On September 3, Texas state governor Greg Abbott estimated that damages will be between $150 billion and $180 billion, surpassing the $120 billion that it took to rebuild New Orleans after Katrina.[99][100] According to weather analytics firm Planalytics, lost revenue to Houston area retailers and restaurants alone will be approximately $1 billion. The Houston area controls 4% of the spending power in the United States.[101]

.jpg.webp)

In September 2017, the Insurance Council of Texas estimated the total insured losses from Hurricane Harvey at $19 billion. This figure represents $11 billion in flood losses insured by the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), $3 billion in "insured windstorm and other storm-related property losses"; and about $4.75 billion in insured flood losses of private and commercial vehicles.[102] By January 1, 2018, payouts from the NFIP reached $7.6 billion against total estimated losses of $8.5–9.5 billion.[103] Economists Michael Hicks and Mark Burton at Ball State University estimated damage in the Houston metropolitan area alone at $198.63 billion.[104] Preliminary reporting from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration set a more concrete total at $125 billion with $41.124 billion coming from Texas alone, making Harvey the 2nd costliest tropical cyclone on record, behind Hurricane Katrina with 2017 costs of $161 billion (after adjusting for inflation).[3][105]

A significant portion of the storm's damages are uninsured losses. Regular homeowner insurance policies generally exclude coverage for flooding, as the NFIP underwrites most flood insurance policies in the US.[106][107] Although the purchase of flood insurance is obligatory for federally guaranteed mortgages for homes within the 100-year flood plain, enforcement of the requirement is difficult and many homes, even within the 100-year flood plain, lack flood insurance.[106] In Harris County, Texas—which includes the city of Houston—only 15% of homes have flood insurance policies issued by the NFIP. Participation in the NFIP is higher, but still low, in neighboring Galveston (41%), Brazoria (26%), and Chambers Counties (21%).[106] Homeowners sued authorities after reservoir releases damaged homes.[108]

Federal Government response

.jpg.webp)

On September 8, President Donald Trump signed into law H.R. 601, which among other spending actions designated $15 billion for Hurricane Harvey relief.[109]

Non-governmental organization response

The American Red Cross, Salvation Army, United Methodist Committee on Relief (UMCOR), Gulf Coast Synod Disaster Relief,[110][111] United States Equestrian Federation, Humane Society of the United States, Knights of Columbus, Samaritan's Purse, Catholic Charities USA, AmeriCares, Operation BBQ relief, many celebrities, and many other charitable organizations provided help to the victims of the storm.[112][113][114] Anarchists (including Antifa) also provided relief.[115][116] Business aviation played a part in the rescue efforts, providing support during the storm as well as relief flights bringing in suppliers in the immediate aftermath.[117]

Volunteers from amateur radio's emergency service wing, the Amateur Radio Emergency Service, provided communications in American Red Cross shelters in South Texas.[118]

Many corporations also contributed to relief efforts. Operation BBQ relief had the help from several local individuals and businesses kick off the support of providing meals for volunteers and victims. Smokers, pallets of wood, and another company came up with the pounds of pork to kick off the support effort.[119] Although Operation BBQ relief has been in effect since May 2011 with the 2011 Joplin tornado, they estimate the Houston 2017 relief project to be their biggest ever.

Operation BBQ relief vendors volunteering for the Houston flood relief estimates that they will serve at least 450,000 meals.[120] On August 27, 2017, it was estimated that Operation BBQ relief will be expecting 25,000 to 30,000 meals a day.[121]

On August 27, 2017, KSL-TV, KSL Newsradio, FM100.3, and 103.5 The Arrow created a fundraiser to help Texas residents impacted by Hurricane Harvey. Because of an anonymous donor willing to match $2 for every $1 raised up to a total of $100,000, Peter Huntsman also agreed to match donations up to $100,000. The combined total of $200,000 was met by August 31, 2017. Their new goal is $1 million.[122]

Foreign government response

Singapore dispatched Boeing CH-47 Chinook helicopters from the Republic of Singapore Air Force to areas affected by the hurricane for humanitarian operations, working alongside the Texas National Guard.[123] Israel pledged $1 million in relief funds for restoration of non-state run communal infrastructure.[124] Mexico sent volunteers from the Mexican Red Cross, firemen from Coahuila, and rescue teams from Guanajuato to Houston to assist in relief.[125] Mexico later rescinded their commitment for aid after Hurricane Katia made landfall on Mexico's Gulf Coast, on September 9, 2017.[126] Venezuela offered $5 million through the state-owned Citgo Petroleum, which operates a refinery in Corpus Christi.[127]

Health and environmental hazards in flood waters

The floodwaters contain a number of hazards to the environment and human health. The Houston Health Department stated that "millions of contaminants" were present in floodwaters.[128] These include E. coli and coliform bacteria; measurements of colony-forming units showed the concentrations were so high that there were risks of contracting flesh-eating disease from the water.[129]

Houston officials stated that the Houston drinking water and sewer systems were intact; however, "hundreds of thousands of people across the 38 Texas counties affected by Hurricane Harvey use private wells, according to an estimate by Louisiana State University researchers, and those people must fend for themselves."[128] Additionally, Harris County, which includes Houston, contains a large number of Superfund-designed brownfield sites that contain a wide variety of toxins and carcinogens.[128] Two Superfund sites in Corpus Christi were flooded.[128]

Baby boom

In the months after the hurricane struck, some hospitals in Texas saw a spike in birth rates, with a 17% increase in birth rates being reported at Corpus Christi Medical Center.[130] Similarly, a large baby boom also occurred after Hurricane Sandy in 2012.[131]

Environmental factors

Houston is located in the southeastern United States on the Gulf Coastal Plain, and its clay-based soils provide poor drainage. The climate of Houston brings very heavy rainfall annually in between April and October, during the Texas Gulf Coast rainy season, together with tidal flood events, which have produced repeated floods in the city ever since its founding in 1836, though the flood control district founded in 1947, aided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, managed to prevent statewide flooding for over 50 years. More recently, residents died in "historic flooding" in May 2015, and in the April 2016 "tax day floods".[132][133] There is a tendency for storms to move very slowly over the region, allowing them to produce tremendous amounts of rain over an extended period, as occurred during Tropical Storm Claudette in 1979, and Tropical Storm Allison in 2001.[134]

The area is a very flat flood plain at shallow gradient, slowly draining rainwater through an intricate network of channels and bayous to the sea. The main waterways, the San Jacinto River and the Buffalo Bayou, meander slowly, laden with mud, and have little capacity for carrying storm water.[135]

Urban development

Houston has seen rapid urban development (urban sprawl), with absorbent prairie and wetlands replaced by hard surfaces which rapidly shed storm water, overwhelming the drainage capacity of the rivers and channels.[136] Between 1992 and 2010, almost 25,000 acres (10,000 ha) of wetlands were lost, decreasing the detention capacity of the region by 4 billion US gal (15 billion L).[137] However, Harvey was estimated to have dropped more than 15 trillion US gal (57 trillion L) of water in the area.[138]

The Katy Prairie in western Harris County, which once helped to absorb floodwaters in the region, has been reduced to one quarter of its previous size in the last several decades due to suburban development, and one analysis discovered that more than 7,000 housing units have been built within the 100-year floodplain in Harris County since 2010.[139]

Subsidence

As Houston has expanded, rainwater infiltration in the region has lessened and aquifer extraction increased, causing the depletion of underground aquifers. When the saturated ground dries, the soil can be compressed and the land surface elevation decreases in a process called subsidence. Subsidence can also occur due to sediment settling. Specifically, regions to the north and west of the Houston metro have seen 10 to 25 millimetres (0.39 to 0.98 in) of subsidence per year.[140] While oil extraction can cause subsidence, in the Houston-Galveston area, most oil has been extracted from sandstone that has relatively negligible ability to compress once oil has been removed. Thus, oil extraction has not resulted in significant subsidence.[140] Further, the volume of oil extraction in the Houston area is too low to cause significant subsidence.[141]

Climate change

The Gulf of Mexico is known for hurricanes in August, so their incidence alone cannot be attributed to global warming, but the warming climate does influence certain attributes of storms. Studies in this regard show that storms tend to intensify more rapidly prior to landfall.[142] Weather events are due to multiple factors, and so cannot be said to be caused by one precondition, but climate change affects aspects of extreme events, and very likely worsened some of the impacts of Harvey.[143] In a briefing, the World Meteorological Organization stated that the quantity of rainfall from Harvey had very likely been increased by climate change.[144]

Harvey approached Houston over sea-surface waters which were significantly above average temperatures. Warm waters provide the main source of energy for hurricanes, and increased ocean heat can result in storms being larger, more intense and longer lasting, in particular bringing greatly increased rainfall.[145][142] Sea level rise added to the resulting problems.[143] According to officials from the Harris County Flood Control District, Harvey caused the third '500-year' flood in three years.[146][147][148] The National Climate Assessment states:

The recent increases in activity are linked, in part, to higher sea surface temperatures in the region that Atlantic hurricanes form in and move through. Numerous factors have been shown to influence these local sea surface temperatures, including natural variability, human-induced emissions of heat-trapping gases, and particulate pollution. Quantifying the relative contributions of natural and human-caused factors is an active focus of research.[149]

Warmer air can hold more water vapor, in accordance with the Clausius–Clapeyron relation, and there has been a global increase of daily rainfall records.[143] Regional sea surface temperatures around Houston have risen around 0.5 °C (32.9 °F) in recent decades, which caused a 3–5% increase in moisture in the atmosphere. This had the effect of allowing Harvey to strengthen more than expected.[150] The water temperature of the Gulf of Mexico was above average for this time of the year, and likely to be a factor in Harvey's impact.[151] Within a week of Harvey, Hurricane Irma formed in the eastern Atlantic, due to the similar conditions involving unusually warm seawater. Some scientists fear this may be becoming a 'new normal'. Also higher sea-water temperatures can make hurricanes more devastating.[152]

The slow movement of Harvey over Texas allowed the storm to drop prolonged heavy rains on the state, as has also happened with earlier storms.[134] Harvey's stalled position was due to weak prevailing winds linked to a greatly expanded subtropical high pressure system over much of the US at the time, which had pushed the jet stream to the north. Research and model simulations have indicated an association between this pattern and human-caused climate change.[150][153]

See also

Notes

- The storm category color indicates the intensity of the hurricane when landfalling in the U.S.

References

- 60 inches of rain fell from Hurricane Harvey in Texas, shattering U.S. storm record – The Washington Post

- Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- "Storm Events Database – Event Details | National Centers for Environmental Information". Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Eric S. Blake; David A. Zelinsky (May 9, 2018). Hurricane Harvey (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- Robbie J. Berg (August 26, 2017). Hurricane Harvey Intermediate Advisory Number 23A (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- "Harvey drops nearly 2 feet of water on Houston area, causing deadly floods". Bangor Daily News. August 27, 2017.

- "Severe Weather Statement: Extreme Wind Warning". National Weather Service in Corpus Christi, Texas. Iowa Environmental Mesonet National Weather Service. August 24, 2017. Archived from the original on April 19, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- Nestel, M. L. (August 25, 2017). "Harvey expected to make landfall as a major hurricane". ABC News. New York City: ABC. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Dart, Tom; Helmore, Edward (August 26, 2017). "Hurricane Harvey: at least one dead in Texas as storm moves inland". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "Cyclone in the U.S." International Charter on Space and Major Disasters. August 24, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Padre Island National Seashore is closing due to Hurricane Harvey, KSAT, August 24, 2017

- "Tornado Event Reports (Texas): August 25-31, 2017". National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- Kevin Sullivan, Arelis R. Hernandez and David A. Fahrenthold (August 29, 2017). "Harvey leaving record rainfall, at least 22 deaths behind in Houston". Chicago Tribune. Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Scheyder, Ernest; Seba, Erwin (August 28, 2017). "Harvey throws a wrench into U.S. energy engine". Reuters. Canary Wharf, London: Thomson Reuters. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Rust, Susanne; Sahagun, Louis (March 5, 2019). "Post-Hurricane Harvey, NASA tried to fly a pollution-spotting plane over Houston. The EPA said no". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- "Harvey's toll on refineries sparks widespread gasoline shortages, price hikes". Houston Chronicle. Houston: Hearst Communications. August 31, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- www.oil-price.net. "Impact of Hurricanes on oil prices". oil-price.net. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- "The Latest: Death toll 31 as 6 more fatalities confirmed". Associated Press. New York City: AP Board of Directors. August 31, 2017. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Houston residents begin 'massive' cleanup as Harvey death toll hits 45". The Guardian. London. September 1, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "DriveTexas.org Proves to be an Invaluable Resource for Texas Travelers During Hurricane Harvey". Newsroom. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- Asher Elbein (September 25, 2017). "How Hurricane Harvey Affected Birds and Their Habitats in Texas". National Audubon Society. Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- Joe Southern (April 3, 2018). "Attwater's prairie chickens dealt critical blow by Hurricane Harvey". Ford Bend Star. Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- Breslin, Sean (August 26, 2017). "Hurricane Harvey Damages Buildings in Rockport; At Least 10 Injured". The Weather Channel. Archived from the original on June 27, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2019.

- Tate, Jennifer Elyse (August 29, 2017). "Storm Summary Number 14 for Tropical Storm Harvey Rainfall and Wind". Weather Prediction Center. College Park, Maryland: United States Government. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Breslin, Sean; Wright, Pam (August 26, 2017). "Hurricane Harvey Update: More Than 100 Evacuated from Damaged Rockport Hotel: Tens of Thousands Without Power". The Weather Channel. Atlanta: Landmark Communications (1982–2008) Consortium made up of The Blackstone Group, Bain Capital, and NBCUniversal (2008–). Archived from the original on August 26, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- Walters, Edgar (August 24, 2018). "No place back home: A year after Harvey, Rockport can't house all its displaced residents". The Texas Tribune. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- Phil McCausland; Daniel Arkin; Kurt Chirbas (August 27, 2017). "Hurricane Harvey: At Least 2 Dead After Storm Hits Texas Coast". NBC News. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- Tate, Jennifer (August 29, 2017). Storm Summary Number 15 for Tropical Storm Harvey Rainfall and Wind. Weather Prediction Center (Report). College Park, Maryland: United States Government. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Roth, David M (January 3, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Avila, Lixion (August 29, 2017). "Tropical Storm Harvey Advisory Number 37". National Hurricane Center. Miami, Florida: United States Government. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Erdman, Jon; Dolce, Chris (August 29, 2017). "It's Not Over: Tropical Storm Harvey Rainfall Sets Preliminary All-Time Lower 48 States Record, Still Soaking Texas, Louisiana". The Weather Channel. Atlanta: Landmark Communications (1982–2008) Consortium made up of The Blackstone Group, Bain Capital, and NBCUniversal (2008–). Archived from the original on November 26, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- National Weather Service Office in Houston, Texas [@NWSHouston] (August 28, 2017). "After checking the rain gauge, a new daily rainfall record was set at the NWS Office of 16.08" beating yesterday's record of 14.40" #houwx" (Tweet). Retrieved August 28, 2017 – via Twitter.

- "24 hours after making landfall, Harvey's rainfall prompts flash flood emergencies in Houston". WHNT-TV. Huntsville, Alabama: Tribune Broadcasting (sale to Sinclair Broadcast Group pending). August 27, 2017. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- National Weather Service Houston [@NWSHouston] (August 31, 2017). "Houston's August 2017 rainfall total (39.11 inches) is more than double the previous wettest month. #txwx #houwx #bcswx #Harvey" (Tweet). Retrieved August 31, 2017 – via Twitter.

- Henson, Bob (August 29, 2017). "Harvey in Houston: Most Extreme Rains Ever For a Major U.S. City". Weather Underground. Retrieved July 29, 2023.

- "Hurricane Harvey". U-SURGE. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Hurricane Harvey storm surge video – CBC News on YouTube

- Fischetti, Mark (August 28, 2017). "Hurricane Harvey: Why Is It So Extreme?". Scientific American. United States: Springer Nature. ISSN 0036-8733. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Eliott C. McLaughlin; Ralph Ellis; Joe Sterling. "Harvey's rain 'beyond anything experienced,' weather service says". CNN. Atlanta: Turner Broadcasting System. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- "Family of six counted among the dead as Harvey death toll rises to 14". Fox News Channel. August 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- St. John Barned-Smith (August 29, 2017). "Houston Police officer drowns in Harvey floodwaters". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Brenda Burr (August 28, 2017). "10-foot floods expected, evacuate by 1 p.m. today officials say". Bay City Tribune. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- "Dam release ramps up Conroe evacuation plans". KTRK. August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "Residents south of Houston urged to leave area after levee breach". KCRA3. August 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Barned-Smith, St. John; Carpenter, Jacob; Foxhall, Emily (August 30, 2017). "Brazoria team works against the clock". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "Corps Releases at Addicks and Barker Dams to begin" (Press release). United States Army Corps of Engineers. August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- "Conditions worsen for West Houston neighborhood". KSAT. August 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "Houston flood: Addicks dam begins overspill". BBC. August 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "NASA's Johnson Space Center Closes for Hurricane Harvey". NASA. August 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- "East Texas county tells residents 'GET OUT OR DIE!'". KSBW. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Brad Penisson (August 31, 2017). "The City of Beaumont has lost water supply". Beaumont, Texas: City of Beaumont, Texas. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Brandon Scott (August 28, 2017). "Mandatory evacuations ordered in parts of Jefferson, Liberty, Tyler counties". KFDM. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Brandon Scott (August 29, 2017). "Beaumont, Texas woman with small child killed in Harvey related flooding". KFDM. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Travis Fedschun (August 30, 2017). "Nation's largest oil refinery in Port Arthur, Texas shut down; mayor says 'whole city is underwater'". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- "U.S.: Hurricane Harvey's Toll on Texas Energy". Stratfor. August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- "ExxonMobil refineries are damaged in Hurricane Harvey, releasing hazardous pollutants". The Washington Post. August 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "The Latest: Death toll 31 as 6 more fatalities confirmed". Miami Herald. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Harvey aftershock: Chemical plant near Houston could explode, CEO says". Fox News Channel. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Harvey Live Updates: In Crosby, Texas, Blasts at a Chemical Plant and More Are Feared". The New York Times. August 31, 2017. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Texas refineries begin restart after hit from Harvey". Reuters. September 2, 2017. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- "Gas prices up to 2-year high after Hurricane Harvey". CBS News. September 1, 2017. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- "Harvey spikes N.J. gas prices ahead of holiday weekend. How high will they go?". NJ.com. September 2017. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- "Cowboys-Texans game relocated to AT&T Stadium". NFL. August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Jori Epstein (August 30, 2017). "Cowboys-Texans game canceled to give Houston players chance to go home after Harvey". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- "TEX-HOU moved to Rays' park; millions donated". MLB. August 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- "Yanks-Rays series off to Citi Field due to Irma". September 8, 2017. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- Astros in St. Pete, but hearts still in Houston, Mlb.com, August 29, 2017

- Pingue, Frank (October 23, 2017). "Astros give Houston boost during Hurricane Harvey recovery". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- Dart, Tom (October 28, 2017). "World Series unites Houston as road to hurricane recovery winds on". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- Baxter, Kevin (October 28, 2017). "Astros playing for more than a title in hurricane-ravaged Houston". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- "LSU-BYU game moving from Houston to New Orleans". SB Nation. August 27, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "No Houston Teams to Compete This Weekend". UHCOUGARS.com. August 29, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Corey Roepken (August 25, 2017). "Dynamo, Dash games postponed due to Hurricane Harvey". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Houston Dynamo & Dash to train in North Texas for remainder of the week". Houston Dynamo. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Corey Roepken (August 31, 2017). "Dynamo, MLS combine for $1 million Hurricane Harvey donation". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "BBVA Compass Stadium at capacity; no longer collecting donations for storm relief". Houston Dynamo. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Blair Shiff; Julia Jacobo; Emily Shapiro (August 29, 2017). "Houston mayor imposes curfew to prevent potential looting". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Alex Pappas (August 29, 2017). "Trump surveys Harvey damage, calls for recovery 'better than ever before'". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Perry Chiaramonte (September 1, 2017). "Trump pushing for $6 billion in Harvey recovery funding". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "Governor Abbott Activates Entire Texas National Guard In Response To Hurricane Harvey Devastation". Office of the Texas Governor (Press release). August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Leada Gore (August 28, 2017). "Hurricane Harvey latest forecast: Texas National Guard activated; Trump responds; how to help". AL.com. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Jake Lowary (August 29, 2017). "Tennessee National Guard: We're ready for Hurricane Harvey response". Tennessean. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Scott Wise (August 30, 2017). "Va. National Guard helps Hurricane Harvey recovery". WTVR. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- "Explosions and Black Smoke Reported at Chemical Plant". The New York Times. August 31, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Edmund D. Fountain and Trip Gabriel (August 30, 2017). "'Cajun Navy' Brings Its Rescue Fleet to Houston's Flood Zone". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Kaya Yurieff (August 30, 2017). "Businesses donate over $72 million to Harvey relief efforts". CNN Money. Archived from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Olivia Pulsinelli (August 29, 2017). "Astros owner, foundation commit $4M to Harvey relief; Crane Worldwide launches donation effort". Houston Business Journal. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "J.J. Watt wins Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year Award for Hurricane Harvey relief efforts". USA Today. February 3, 2018. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Scott Polacek (August 29, 2017). "Texas Rangers Donate $1 Million to Hurricane Harvey Relief". Bleacher Report. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Sarah Polus (August 30, 2017). "Celebrities open their hearts – and checkbooks – to Harvey victims". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Erin Jensen (August 29, 2017). "Leonardo DiCaprio, the Kardashians, more celebs pledge donations for Hurricane Harvey relief efforts". USA Today. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Manchester, Julia; Greenwood, Max (2017-09-16). "Trump makes good on pledge to donate to Harvey relief". The Hill. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

The Hill confirmed with multiple groups that they received the funds this week.

- Ana Calderone (August 30, 2017). "Rachael Ray Donates $1 Million to Support Animal Rescue in Texas Flood Areas". People. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables update (PDF) (Report). United States National Hurricane Center. January 12, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- "Assessing the U.S. Climate in 2018". National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI). 2019-02-06. Retrieved 2019-02-09.

- Don Lee (September 1, 2017). "Harvey is likely to be the second-most costly natural disaster in U.S. history". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- "Insured Natural Disaster Losses in 2017 Were 38% of Economic Costs of $353B: Aon". Insurance Journal. January 24, 2018. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- Doyle Rice (August 30, 2017). "Harvey to be costliest natural disaster in U.S. history, with an estimated cost of $190 billion". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Gary McWilliams; Parraga Marianna (3 September 2017). "Texas governor says Harvey damage could reach $180 billion". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Oliver Milman (September 3, 2017). "Harvey recovery bill expected to exceed the $120bn required after Katrina". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Adrianne Pasquarelli (August 28, 2017). "Harvey Blasts Brands: Could Cost More Than $1B in Sales". Advertising Age. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- "ICT Pegs Hurricane Harvey Insured Losses at $19B". Insurance Journal. September 15, 2017. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- Andrew G. Simpson (January 8, 2018). "FEMA Expands Flood Reinsurance Program with Private Reinsurers for 2018". Insurance Journal. Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- Michael Hicks and Mark Burton (September 8, 2017). Hurricane Harvey: Preliminary Estimates of Commercial and Public Sector Damages on the Houston Metropolitan Area (PDF) (Report). Ball State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Table of Events (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. January 8, 2018. Archived from the original on January 21, 2018. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- Mary Williams Walsh (August 28, 2017). "Homeowners (and Taxpayers) Face Billions in Losses From Harvey Flooding". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Chris Isidore (August 26, 2017). "Most homes in Tropical Storm Harvey's path don't have flood insurance". CNN. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Sims, Bryan (September 13, 2017). "Harvey storm-water releases were unlawful government takings: lawsuits". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- "News Wrap: Trump signs $15 billion Hurricane Harvey relief bill". PBS Newshour. September 8, 2017. Archived from the original on September 28, 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "Gulf Coast Synod Disaster Relief". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- "Hurricane Harvey – Gulf Coast Synod". Gulf Coast Synod. 2017-08-27. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- "Salvation Army Accepting Hurricane Harvey Relief Donations In Tulsa". News On 6 Tulsa. September 1, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Janet Patton (September 1, 2017). "Harvey equine relief tops $150,000; supply list available for donors". Lexington Herald Leader. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Perri Blumberg (August 30, 2017). "Animal Rescue Groups in Texas Need Your Help—Here's What You Can Do". Yahoo News Southern Living. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "The Red Cross Won't Save Houston. Texas Residents Are Launching Community Relief Efforts Instead". Democracy Now!. 2017-08-30. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- Bernd, Candice (September 7, 2017). "Antifa and leftists organize mutual aid and rescue networks in Houston". Salon. Archived from the original on August 30, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- Gollan, Doug. "After Harvey, As Irma Bears Down On Florida, Here's How Business Aviation Plays A Critical Role". Forbes. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "Amateur Radio Volunteers Assisting Where Needed in Hurricane Response". ARRL. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Greg Morago (August 30, 2017). "Operation BBQ Relief pulls into Houston to comfort, nourish with smoked meat". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- Kevin Kilbane (September 1, 2017). "Fort Wayne residents pitching in to help Hurricane Harvey victims". Fort Wayne News Sentinel. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- Mike Lacy (August 27, 2017). "Operation BBQ Relief ready and waiting to help flood victims". WLOX ABC News. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "KSL Hope for Houston: Help us raise $1M to help with Harvey recovery". KSL News. 2017-08-31. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- "RSAF Chinooks arrive to assist in Hurricane Harvey disaster relief". Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Sarah Levi (September 4, 2017). "In Wake of Harvey Devastation, Israel Pledges $1M. to Houston's Jewish Community". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- Corchado, Alfredo (August 31, 2017). "Abbott says Texas will accept Mexican offer of Hurricane Harvey relief". Dallas News. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- "Mexico says it will not be possible to help Texas with recovery efforts". Newsweek. 2017-09-11. Archived from the original on September 19, 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-19.

- Amanda Erickson (August 30, 2017). "America sanctioned Venezuela. Then it offered $5 million in aid to Harvey victims". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Hiroko Tabuchi & Shelia Kaplan, A Sea of Health and Environmental Hazards in Houston's Floodwaters Archived September 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times (August 31, 2017).

- "Floodwater from Harvey loaded with E. coli". Erin Burnett OutFront. CNN. September 1, 2017. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- Danielle Garrand (May 29, 2018). "Hurricane Harvey babies: Some hospitals see spike in births months after the storm". CBS News. Archived from the original on June 1, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- Josh Levs (July 24, 2013). "Is the post-Sandy baby boom real?". CNN. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- Adam Gabbatt (August 28, 2017). "What makes Houston so vulnerable to serious floods?". the Guardian. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Justin Fox (August 29, 2017). "How to Make 500-Year Storms Happen Every Year". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- "How A Warmer Climate Helped Shape Harvey". NPR.org. August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Ralph Vartabedian (August 29, 2017). "For years, engineers have warned that Houston was a flood disaster in the making. Why didn't somebody do something?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Manny Fernandez; Richard Fausset (August 27, 2017). "A Storm Forces Houston, the Limitless City, to Consider Its Limits". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Campoy, Ana; Yanofsky, David (August 29, 2017). "Houston's flooding shows what happens when you ignore science and let developers run rampant". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- Herriges, Daniel (August 30, 2017). "Houston isn't flooded because of its land use planning". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- Henry Grabar (August 27, 2017). "Houston Wasn't Built for a Storm Like This". Slate. Archived from the original on August 29, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2017.

- Jiangbo Yu; et al. (July 2, 2014). "Is There Deep-Seated Subsidence in the Houston-Galveston Area?". International Journal of Geophysics. 2014: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2014/942834.

- "Oil Wells and Production in Harris County, TX". Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- "What you can and can't say about climate change and Hurricane Harvey". The Washington Post. August 27, 2017. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Stefan Rahmstorf. "Storm Harvey: impacts likely worsened due to global warming". Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research Research Portal. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- Tom Miles (August 29, 2017). "Storm Harvey's rainfall likely linked to climate change: U.N." Reuters U.K. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- "Did Climate Change Intensify Hurricane Harvey?". The Atlantic. August 27, 2017. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- "Houston is experiencing its third '500-year' flood in 3 years. How is that possible?". The Washington Post. August 30, 2017. Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Joyce, Christpher (September 8, 2017). "Hurricanes Are Sweeping The Atlantic. What's The Role Of Climate Change?". NPR. Washington, D.C.: National Public Radio, Inc. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Meyer, Robinson (August 27, 2017). "Did Climate Change Intensify Hurricane Harvey?". The Atlantic. Washington, D.C.: Atlantic Media. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- "Extreme Weather". National Climate Assessment. Archived from the original on August 30, 2017. Retrieved August 30, 2017.

- Michael E. Mann (August 28, 2017). "It's a fact: climate change made Hurricane Harvey more deadly". the Guardian. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- "How Hurricane Harvey Became So Destructive". The New York Times. August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Watts, Jonathan (September 6, 2017). "Twin megastorms have scientists fearing this may be the new normal". The Guardian. Kings Place, London. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Michael E. Mann; Stefan Rahmstorf; Kai Kornhuber; Byron A. Steinman; Sonya K. Miller; Dim Coumou (March 27, 2017). "Influence of Anthropogenic Climate Change on Planetary Wave Resonance and Extreme Weather Events". Scientific Reports. Springer Nature. 7: 45242. Bibcode:2017NatSR...745242M. doi:10.1038/srep45242. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5366916. PMID 28345645.