Egon Schiele

Egon Leo Adolf Ludwig Schiele (German: [ˈeːɡɔn ˈʃiːlə] ⓘ; 12 June 1890 – 31 October 1918) was an Austrian Expressionist painter. His work is noted for its intensity and its raw sexuality, and for the many self-portraits the artist produced, including nude self-portraits. The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele's paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism. Gustav Klimt, a figurative painter of the early 20th century, was a mentor to Schiele.

Egon Schiele | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait with Physalis, 1912 | |

| Born | Egon Leo Adolf Ludwig Schiele 12 June 1890 |

| Died | 31 October 1918 (aged 28) |

| Nationality | Austrian |

| Education | Akademie der Bildenden Künste |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, printmaking |

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Expressionism |

Biography

Early life

Schiele was born in 1890 in Tulln, Lower Austria. His father, Adolf Schiele, the station master of the Tulln station in the Austrian State Railways, was born in 1851 in Vienna to Karl Ludwig Schiele, a German from Ballenstedt and Aloisia Schimak; Egon Schiele's mother Marie, née Soukup, was born in 1861 in Český Krumlov (Krumau) to Franz Soukup, a Czech father from Mirkovice, and Aloisia Poferl, a German Bohemian mother from Český Krumlov.[1][2] As a child, Schiele was fascinated by trains, and would spend many hours drawing them, to the point where his father felt obliged to destroy his sketchbooks. When he was 11 years old, Schiele moved to the nearby city of Krems (and later to Klosterneuburg) to attend secondary school. To those around him, Schiele was regarded as a strange child. Shy and reserved, he did poorly at school except in athletics and drawing,[3] and was usually in classes made up of younger pupils. He also displayed incestuous tendencies towards his younger sister Gertrude (who was known as Gerti), and his father, well aware of Egon's behaviour, was once forced to break down the door of a locked room that Egon and Gerti were in to see what they were doing (only to discover that they were developing a film). When he was sixteen he took the twelve-year-old Gerti by train to Trieste without permission and spent a night in a hotel room with her.[4]

Academy of Fine Arts

When Schiele was 14 years old, his father died from syphilis, and he became a ward of his maternal uncle, Leopold Czihaczek, also a railway official.[2] Although he wanted Schiele to follow in his footsteps, and was distressed at his lack of interest in academia, he recognised Schiele's talent for drawing and unenthusiastically allowed him a tutor, the artist Ludwig Karl Strauch. In 1906 Schiele applied at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) in Vienna, where Gustav Klimt had once studied. Within his first year there, Schiele was sent, at the insistence of several faculty members, to the more traditional Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna in 1906. His main teacher at the academy was Christian Griepenkerl, a painter whose strict doctrine and ultra-conservative style frustrated and dissatisfied Schiele and his fellow students so much that he left three years later.

Klimt and first exhibitions

In 1907, Schiele sought out Gustav Klimt, who generously mentored younger artists. Klimt took a particular interest in the young Schiele, buying his drawings, offering to exchange them for some of his own, arranging models for him and introducing him to potential patrons. He also introduced Schiele to the Wiener Werkstätte, the arts and crafts workshop connected with the Secession. Schiele's earliest works between 1907 and 1909 contain strong similarities with those of Klimt,[5] as well as influences from Art Nouveau.[6] In 1908 Schiele had his first exhibition, in Klosterneuburg. Schiele left the academy in 1909, after completing his third year, and founded the Neukunstgruppe ("New Art Group") with other dissatisfied students. In his early years, Schiele was strongly influenced by Klimt and Kokoschka. Although imitations of their styles, particularly with the former, are noticeably visible in Schiele's first works, he soon evolved his own distinctive style.

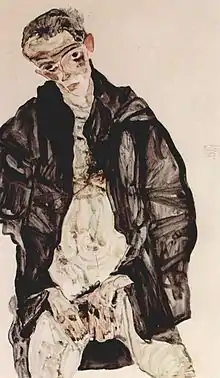

Klimt invited Schiele to exhibit some of his work at the 1909 Vienna Kunstschau, where he encountered the work of Edvard Munch, Jan Toorop, and Vincent van Gogh among others. Once free of the constraints of the academy's conventions, Schiele began to explore not only the human form, but also human sexuality. Schiele's work was already daring, but it went a bold step further with the inclusion of Klimt's decorative eroticism and with what some may like to call figurative distortions, that included elongations, deformities, and sexual openness. Schiele's self-portraits helped re-establish the energy of both genres with their unique level of emotional and sexual honesty and use of figural distortion in place of conventional ideals of beauty. He also painted tributes to Van Gogh's Sunflowers as well as landscapes and still lifes.[7]

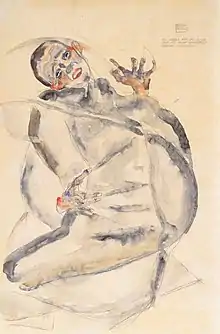

In 1910, Schiele began experimenting with nudes and within a year a definitive style featuring emaciated, sickly-coloured figures, often with strong sexual overtones. Schiele also began painting and drawing children.[8] Schiele's self portrait, Kneeling Nude with Raised Hands (1910), is considered among the most significant nude art pieces made during the 20th century. Schiele's radical and developed approach towards the naked human form challenged both scholars and progressives alike. This unconventional piece and style went against strict academia and created a sexual uproar with its contorted lines and heavy display of figurative expression. At the time, many found the explicitness of his works disturbing.

From then on, Schiele participated in numerous group exhibitions, including those of the Neukunstgruppe in Prague in 1910 and Budapest in 1912; the Sonderbund, Cologne, in 1912; and several Secessionist shows in Munich, beginning in 1911. In 1911, Schiele met the seventeen-year-old Walburga (Wally) Neuzil, who lived with him in Vienna and served as a model for some of his most striking paintings. Very little is known of her, except that she had previously modelled for Gustav Klimt and might have been one of his mistresses. Schiele and Wally wanted to escape what they perceived as the claustrophobic Viennese milieu, and went to the small town of Český Krumlov (Krumau) in southern Bohemia. Krumau was the birthplace of Schiele's mother; today it is the site of a museum dedicated to Schiele. Despite Schiele's family connections in Krumau, he and his lover were driven out of the town by the residents, who strongly disapproved of their lifestyle, including his alleged employment of the town's teenage girls as models. Progressively, Schiele's work grew more complex and thematic, and he eventually would begin dealing with themes such as death and rebirth.[9]

Neulengbach and imprisonment

Together the couple moved to Neulengbach, 35 km (22 mi) west of Vienna, seeking inspirational surroundings and an inexpensive studio in which to work. As it was in the capital, Schiele's studio became a gathering place for Neulengbach's delinquent children. Schiele's way of life aroused much animosity among the town's inhabitants, and in April 1912 he was arrested for seducing a young girl of 13,[10] below the 14-year-old age of consent.[11]

When the police came to his studio to place Schiele under arrest, they seized more than a hundred drawings which they considered pornographic. Schiele was imprisoned while awaiting his trial. When his case was brought before a judge, the charges of seduction and abduction were dropped, but the artist was found guilty of exhibiting erotic drawings in a place accessible to children. In court, the judge burned one of the offending drawings ("depicting a very young girl dressed only above the waist"[12]) over a candle flame. The twenty-one days he had already spent in custody were taken into account, and he was sentenced to a further three days' imprisonment. While in prison, Schiele created a series of 12 paintings depicting the difficulties and discomfort of being locked in a jail cell.

In 1913, the Galerie Hans Goltz, Munich, mounted Schiele's first solo show. A solo exhibition of his work took place in Paris in 1914.[13]

World War I to death

In 1914, Schiele glimpsed the sisters Edith and Adéle Harms, who lived with their parents across the street from his studio in the Viennese district of Hietzing, 101 Hietzinger Hauptstraße. They were a middle-class family and Protestant by faith; their father was a master locksmith. In 1915, Schiele chose to marry the more socially acceptable Edith, but had apparently expected to maintain a relationship with Wally. However, when he explained the situation to Wally, she left him immediately and never saw him again. This abandonment led him to paint Death and the Maiden, where Wally's portrait is based on a previous pairing, but Schiele's is newly struck. (In February 1915, Schiele wrote a note to his friend Arthur Roessler stating: "I intend to get married, advantageously. Not to Wally.") Despite some opposition from the Harms family, Schiele and Edith were married on 17 June 1915, the anniversary of the wedding of Schiele's parents.[14]

Although Schiele avoided conscription for almost a year, World War I now began to shape his life and work. Three days after his wedding, Schiele was ordered to report for active service in the army where he was initially stationed in Prague. Edith came with him and stayed in a hotel in the city, while Egon lived in an exhibition hall with his fellow conscripts. They were allowed by Schiele's commanding officer to see each other occasionally.[15][16]

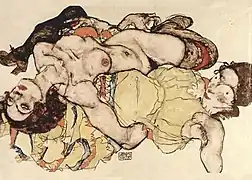

During the war, Schiele's paintings became larger and more detailed. His military service, however, gave him limited time, and much of his output consisted of linear drawings of scenery and military officers. Around this time, Schiele also began experimenting with the themes of motherhood and family.[13] His wife Edith was the model for most of his female figures, but during the war (due to circumstance) many of his sitters were male. Since 1915, Schiele's female nudes became fuller in figure, but many were deliberately illustrated with a lifeless doll-like appearance.

Despite his military service, Schiele was still exhibiting in Berlin. He also had successful shows in Zürich, Prague, and Dresden. His first duties consisted of guarding and escorting Russian prisoners. Because of his weak heart and his excellent handwriting, Schiele was eventually given a job as a clerk in a POW camp near the town of Mühling. There, he was allowed to draw and paint imprisoned Russian officers; his commander, Karl Moser (who assumed that Schiele was a painter and decorator when he first met him), even gave him a disused store room to use as a studio. Since Schiele was in charge of the food stores in the camp, he and Edith could enjoy food beyond rations.[17]

By 1917, he was back in Vienna and able to focus on his artistic career. His output was prolific, and his work reflected the maturity of an artist in full command of his talents. He was invited to participate in the Secession's 49th exhibition, held in Vienna in 1918. Schiele had fifty works accepted for this exhibition, and they were displayed in the main hall. He also designed a poster for the exhibition; it was reminiscent of the Last Supper, with a portrait of himself in the place of Christ. The show was a triumphant success. As a result, prices for Schiele's drawings increased and he received many portrait commissions.[18]

In the autumn of 1918, the Spanish flu pandemic reached Vienna. Edith, who was six months pregnant, died from the disease on 28 October. Schiele died only three days after his wife. He was 28 years old. During the three days between their deaths, Schiele drew a few sketches of Edith.[19]

Style

Some critics such as Jane Kallir have commented upon Schiele's work as being grotesque, erotic, pornographic, or disturbing, focusing on sex, death, and discovery. He focused on portraits of others as well as himself. In his later years, while he still worked often with nudes, they were done in a more realist fashion.[13] From a young age, Schiele drew with 'manic fluency'.[20]

Art critic Martin Gayford wrote in The Spectator: 'He [Schiele] found his distinctive style very early. His entire oeuvre is that of a young man; most of the work in the first of the two rooms of this densely packed little exhibition dates from 1910 to 1911, when Schiele (1890–1918) was just 20. That helps to explain some tendencies: a half-disgusted preoccupation with sexuality and a similarly queasy fascination with examining his naked self. The male figures mainly seem to have been modelled by the artist, though it is hard to be certain since the head is often not included.'[20]

Kallir and scholar Gerald Izenberg regard Schiele as fluid in sexuality and gender. Kallir says Schiele was "struggling with his own sexual feelings and gender norms" during a historical period of shifting gender expectations, the early women's movement, and criminalization of homosexuality. Some critics in the 21st century read his artwork as queer.[21][22]

A less known fact about Schiele's career is that, during his studies at the School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna, he explored sculpture and created a number of small-scale clay and plaster sculptures.[23]

Legacy

Schiele was the subject of the 1980 biographical film Excess and Punishment (aka Egon Schiele – Exzess und Bestrafung), originating in Germany with a European cast that explores Schiele's artistic demons leading up to his early death. The film was directed by Herbert Vesely and stars Mathieu Carrière as Schiele, Jane Birkin as his early artistic muse Wally Neuzil, Christine Kaufman as his wife, Edith Harms, and Kristina Van Eyck as her sister, Adele Harms. Also in 1980, the Arts Council of Great Britain produced a documentary film, Schiele in Prison, which looked at the circumstances of Schiele's imprisonment and the veracity of his diary.[24] In 2016 another biographical film was released, Egon Schiele: Death and the Maiden (German: Egon Schiele: Tod und Mädchen).[25]

Joanna Scott's 1990 novel Arrogance was based on Schiele's life and makes him the main figure. His life was also depicted in a theatrical dance production by Stephan Mazurek called Egon Schiele, presented in May 1995, for which Rachel's, an American post-rock group, composed a score titled Music for Egon Schiele.[26] For The Featherstonehaughs contemporary dance company, Lea Anderson choreographed The Featherstonehaughs Draw On The Sketchbooks Of Egon Schiele in 1997.[27] Glen Hansard, lead singer of Irish band The Frames, said (of writing the song Santa Maria) "...With Santa Maria, I was trying to write a song about Egon Schiele, and about him and his girlfriend, while they were both dying from Spanish flu...".https://www.threemonkeysonline.com/excreting-songs-glen-hansard-of-the-frames/3/

Schiele's life and work have also been the subject of essays, including a discussion of his works by fashion photographer Richard Avedon in an essay on portraiture entitled "Borrowed Dogs."[28] Mario Vargas Llosa uses the work of Schiele as a conduit to seduce and morally exploit a main character in his 1997 novel The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto.[29] Wes Anderson's film The Grand Budapest Hotel features a painting by Rich Pellegrino that is modeled after Schiele's style which, as part of a theft, replaces a so-called Flemish/Renaissance masterpiece, but is then destroyed by the angry owner when he discovers the deception.[30] The cover of David Bowie's 1979 Lodger album is inspired by Schiele's self-portraits[31] and an image of Schiele appears on the cover of the 2013 single The Stars (Are Out Tonight).[32]

Julia Jordan based her 1999 play Tatjana in Color, which was produced off-Broadway at The Culture Project during the fall of 2003, on a fictionalization of the relationship between Schiele and the 12-year-old Tatjana von Mossig, the Neulengbach girl whose morals he was ultimately convicted of corrupting for allowing her to see his paintings.[33] The opening chapters of Guy Mankowski's 2017 novel An Honest Deceit were cited to be heavily influenced by Schiele's paintings; in particular his portrayals of his sister, Gertrude.[34]

.jpg.webp)

Art collections

The Leopold Museum, Vienna houses perhaps Schiele's most important and complete collection of work, featuring over 200 exhibits. The museum sold one of these, Houses With Colorful Laundry (Suburb II), for $40.1 million at Sotheby's in 2011.[35] Other notable collections of Schiele's art include the Egon Schiele-Museum, Tulln, the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, and the Albertina Graphic Collection, both in Vienna. Viktor Fogarassy collected works by Schiele, including Dämmernde Stadt.[36]

Nazi-looted art

Egon Schiele had among his admirers many Jewish art collectors whose collections were looted under the Nazis: in Germany from 1933, in Austria from the Anschluss of 1938, and in France from the German occupation of 1940. As a result, numerous restitution cases in the 21st century involve artworks by Schiele. Egon Schiele's Dead City, "Woman in Black Pinafore" (1911) and "Woman Hiding Her Face" (1912) were owned by Jewish cabaret artist and film star Fritz Grünbaum before the Nazis deported him to the Dachau concentration camp.[37][38] Krumau (1916) was owned by Daisy Hellmann until it was seized by Nazis in 1942.[39][40] She first made a restitution claim in 1948 but her heirs were not able to recover the Schiele until 2002: Austria's Nazi looting organization, the Vugesta, had auctioned Krumau at the Dorotheum in Vienna on 24–27 February 1942, where the Sanct Lucas gallery bought it on behalf of Wolfgang Gurlitt. In 1953, the City of Linz acquired it for the Neue Galerie in Linz.[41] The 1917 painting by Egon Schiele, Portrait of the Artist's Wife was owned by Karl Mayländer, a Jewish businessman in Vienna who was killed in Auschwitz. Robert "Robin" Owen Lehman, the son of Robert Lehman, bought Portrait of the Artist's Wife (1917) in 1964 from Marlborough Gallery in London.[42] Four Trees / Autumn Allée was owned by Josef Morgenstern who was arrested and deported to Auschwitz, where he was murdered.[43][44]

The art gallery of the Jewish art dealer Lea Bondi Jaray, owner of the famous Portrait of Wally, was seized by the Nazis prior to his escaping to London.[45] Wilted Sunflowers, which had been owned by Jewish art collector Karl Grunwald and seized by Nazis in Strasbourg, was discovered after a private collector took it to Christies for evaluation in 2005.[46][47] Portrait of Wally, a 1912 portrait, was purchased by Rudolf Leopold in 1954 and became part of the collection of the Leopold Museum when it was established by the Austrian government, purchasing more than 5,000 pieces that Leopold had owned. After a 1997–1998 exhibit of Schiele's work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the painting was seized by order of the New York County District Attorney and had been tied up in litigation by heirs of its former owner who claim that the painting was Nazi plunder and should be returned to them.[48][49]

The dispute was settled on 20 July 2010 and the picture subsequently purchased by the Leopold Museum for US$19 million.[50] In 2013, the museum sold three drawings by Schiele for £14 million at Sotheby's London in order to settle the restitution claim over its 1914 Schiele painting Houses by the Sea.[51] The most expensive, Liebespaar (Selbstdarstellung mit Wally) (1914/15), or Two lovers (Self Portrait With Wally), raised the world auction record for a work on paper by the artist to £7.88 million.[52] On 21 June 2013 Auctionata in Berlin sold a watercolor from 1916, Reclining Woman, at an online auction for €1.827 million (US$2.418 million). This is a world record for the most expensive work of art ever sold at an online auction.[53][54][55]

Self-portraits

Self-portrait with striped shirt, 1910 Leopold Museum

Self-portrait with striped shirt, 1910 Leopold Museum Self-portrait grimacing, 1910

Self-portrait grimacing, 1910 Self-portrait with black clay pot, 1911

Self-portrait with black clay pot, 1911 Self-portrait with lowered head, 1912 Leopold Museum

Self-portrait with lowered head, 1912 Leopold Museum I shall endure for art and for the happiness of my lover. Self-portrait of Schiele in jail, 1912

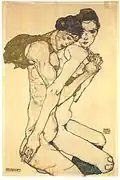

I shall endure for art and for the happiness of my lover. Self-portrait of Schiele in jail, 1912_(LOVERS_-_SELF-PORTRAIT_WITH_WALLY).jpg.webp) Lovers – Self-Portrait with Wally, c. 1914 – 1915

Lovers – Self-Portrait with Wally, c. 1914 – 1915 Self-portrait, 1914

Self-portrait, 1914 Self-portrait, 1915

Self-portrait, 1915 Self-portrait depicting masturbation, 1911

Self-portrait depicting masturbation, 1911

Figurative works

Girl with black hair, 1910

Girl with black hair, 1910 Reclining nude, 1910

Reclining nude, 1910 Nude with Red Garters, 1911

Nude with Red Garters, 1911 Semi-nude Reclining 1911

Semi-nude Reclining 1911 Walburga Neuzil in black stockings, 1913

Walburga Neuzil in black stockings, 1913 Friendship, 1913

Friendship, 1913 Seated female nude with elbows propped, 1914

Seated female nude with elbows propped, 1914 Frederike Beer, 1914

Frederike Beer, 1914 Blonde girl in green stockings, 1914

Blonde girl in green stockings, 1914 Green Stockings, 1914

Green Stockings, 1914 Two Women

Two Women Mother with two children II, 1915 Leopold Museum

Mother with two children II, 1915 Leopold Museum Children

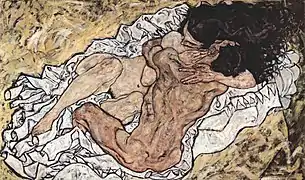

Children Pair embracing, 1917

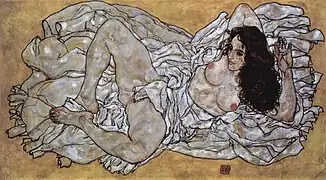

Pair embracing, 1917 Reclining woman, 1917 Leopold Museum

Reclining woman, 1917 Leopold Museum Kneeling Girl, Resting on Both Elbows 1917 Leopold Museum

Kneeling Girl, Resting on Both Elbows 1917 Leopold Museum

Sitting girl, 1917

Sitting girl, 1917 Nude, 1917

Nude, 1917_-_4277_-_%C3%96sterreichische_Galerie_Belvedere.jpg.webp) The Family, 1918

The Family, 1918%252C_1913%252C_NGA_71829.jpg.webp) Dancer (Die Tänzerin), 1913

Dancer (Die Tänzerin), 1913

Landscapes

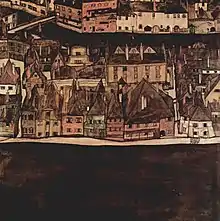

Die kleine Stadt III, 1912–1913, view of Krumau an der Moldau Leopold Museum

Die kleine Stadt III, 1912–1913, view of Krumau an der Moldau Leopold Museum_by_Egon_Schiele%252C_1913.jpg.webp) Dämmernde Stadt, 1913

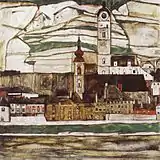

Dämmernde Stadt, 1913 Stein an der Donau II, 1913

Stein an der Donau II, 1913 The Bridge (Die Brücke), 1913

The Bridge (Die Brücke), 1913 House with Shingle Roof (Old House II), 1915 Leopold Museum

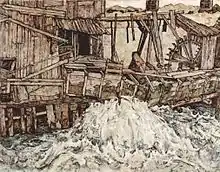

House with Shingle Roof (Old House II), 1915 Leopold Museum Old Mill (Alte Mühle), 1916

Old Mill (Alte Mühle), 1916 Four trees (Vier Bäume), 1917

Four trees (Vier Bäume), 1917 Houses with Clothelines (Häuser mit Wäscheleinen oder Vorstadt)

Houses with Clothelines (Häuser mit Wäscheleinen oder Vorstadt)

References

- Wladika 2012, p. 13.

- Sabarsky 2000, pp. 31–38.

- Whitford 1981, p. 30.

- Whitford 1989, p. 29.

- Kallir 2003, pp. 46, 52, 60.

- Kallir 2003, p. 41.

- "Egon Schiele: Erotic, Grotesque and on Display". ARTINFO. 1 April 2005. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kallir 2003, pp. 86, 88, 123.

- Kallir 2003, pp. 224, 230, 231.

- Johnson, Ken (21 October 2005). "The Wider, Not Wilder, Egon Schiele". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Kallier, Jane (June 2018). "Egon Schiele was not a sex offender". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Blackshaw, Gemma (2020). "Egon Schiele's Passion: Spirituality and Sexuality, 1912-15". In Natter, Tobias (ed.). Egon Schiele. The Complete Paintings 1909–1918. Köln: Taschen. p. 223. ISBN 978-3-8365-8125-7.

- Kallir 2003, pp. 277, 362, 444.

- "Family tree of Adolf Eugen SCHIELE". Geneanet. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- "Life and Work of Egon Schiele, Austrian Expressionist Painter". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- Lamb, Bill (31 December 2018). ""Life and Work of Egon Schiele, Austrian Expressionist Painter."". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- Whitford 1981, pp. 164–168.

- Dabrowski, Magdalena; Leopold, Rudolf (1997). ""Egon Schiele : The Leopold Collection, Vienna."" (PDF). Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- Frank Whitford, Expressionist Portraits, Abbeville Press, 1987, p. 46. ISBN 0-89659-780-6.

- Gayford, Martin (8 November 2014). "Egon Schiele at the Courtauld: a one-note samba of spindly limbs, nipples and pudenda | The Spectator". The Spectator. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- Morrish, Lydia (3 December 2018). "The hidden LGBTQ legacy of Egon Schiele's art works". Dazed & Confused Magazine.

- "Egon Schiele: Expressionist Art and Masculine Crisis". Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 26 (3): 462–483. June 2006. doi:10.2513/s07351690pi2603_11 (inactive 1 August 2023).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2023 (link) - https://www.artnet.com/auctions/artists/egon-schiele/selbstbildnis-8.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Schiele In Prison". Arts on Film Archive. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Egon Schiele: Death and the Maiden (Egon Schiele: Tod und Mädchen)". Cineuropa - the best of european cinema. Retrieved 21 April 2023.

- Roberts, Michael; Kiser, Amy (4 April 1996). "Playlist". Denver Music. Westword.com. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "The Cholmondeleys & The Featherstonehaughs :: Current productions". Archived from the original on 11 September 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- "Performance & Reality: Essays from Grand Street (magazine)," edited by Ben Sonnenberg

- "The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto – Mario Vargas Llosa".

- "Is The Grand Budapest Hotel's 'Boy with Apple' artwork plausible?". The Observer. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "On David Bowie's life as an artist and art journalist". 22 June 2023.

- "David Bowie announces new single and album details". TheGuardian.com. 18 February 2013.

- "Jordan, Jordan Everywhere". theatermania.com. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- "Features: Bunch Of Fives – Guy Mankowski". Narc Magazine. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- "Schiele and Picasso Draw Interest at London Auctions". The New York Times. 23 June 2011.

- Kronsteiner, Olga (5 October 2018). "Kunstverkauf / Warum die Versteigerung dieses Gemäldes von Egon Schiele eine Sensation ist". Der Standard (in German). Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "Murder, Mystery and Egon Schiele's "Dead City": Presentation by Raymond Dowd, Jewish Museum Berlin, 19.30pm 18 May 2009". www.lootedart.com. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "NY Appeals Court Explains Why Nazi-Stolen Paintings Belong With Jewish Collector's Heirs". www.lootedart.com. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Artdaily. "Sotheby's to Sell Restituted Masterpiece by Egon Schiele". artdaily.cc. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Cases: Krumau, 1916 or 'Städtchen am Fluß' by Egon Schiele: Restitution decision by the City of Linz December 2002". www.lootedart.com. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Cases: Krumau, 1916 or 'Städtchen am Fluß' by Egon Schiele: Restitution decision by the City of Linz December 2002". www.lootedart.com. Retrieved 25 March 2021.

In late 2002, the City of Linz decided to return the painting 'Krumau, 1916' by Egon Schiele to the heirs of Daisy Hellmann. In June 1948, Daisy Hellmann – then residing in Sao Paolo, Brasil – deposited a claim for the restitution of the Schiele painting 'Krumau, 1916' at the Restitution Commission of the Provincial Court in Graz (Styria). Hellmann had to leave the painting behind when fleeing Vienna in 1938. The Schiele was looted by the Vugesta and put up for auction at the Dorotheum on 24–27 February 1942, where it was bought by the Viennese Sanct Lucas gallery for RM 1,800 on behalf of the art dealer Wolfgang Gurlitt. In 1953, the painting was among the group of works the City of Linz acquired from Gurlitt's collection for the 'Neue Galerie' in Linz.

- "Who really owns this Schiele watercolour Portrait of the Artist's Wife?". The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. 29 October 2019. Archived from the original on 30 November 2021. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- "CASE STUDIES" (PDF). COMMISSION FOR PROVENANCE RESEARCH & ADVISORY BOARD.

- "Art Restitution Advisory Council Recommends Restitution of Egon Schiele Painting at the Belvedere". Jewish News From Austria. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "3 Cases That Explain Why Restituting Nazi Looted Art Is So Difficult". www.lootedart.com. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- "Family reunited with Schiele masterpiece stolen 60 years ago by Nazis – Europe, World – The Independent". Independent.co.uk. 18 September 2009. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- "REDISCOVERED MASTERPIECE" (PDF). Christies.

In 1938, the year Hitler annexed Austria, Grünwald, who by this time had amassed a first rate collection of Austrian art, fled Vienna for France. Settling in Paris, the collector moved fifty paintings out of Austria, including the present work. Unfortunately, the Grünwald collection, including Wilted Sunflowers (Autumn Sun II), was confiscated in Strasbourg, where it had been placed in storage by Grünwald and sold at auction in 1942

- Marilyn Henry (24 July 2010). "Justice is Done, Finally". Jerusalem Post.

- Bayzler, Michael J.; and Alford, Roger P. Holocaust restitution: perspectives on the litigation and its legacy, p. 281. NYU Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8147-9943-4. Accessed 5 July 2010.

- Kennedy, Randy (20 July 2010). "Leopold Museum to Pay $19 Million for Painting Seized by Nazis". The New York Times.

- Scott Reyburn (6 February 2013), Picasso's Portrait of Lover Stars in $190 Million Auction Bloomberg.

- Souren Melikian (6 February 2013), At Sotheby's Sale, Estimates Prove to Be Just Wild Guesses The New York Times.

- "Schiele bringt Rekordpreis bei Online-Auktion" (in German). Welt.de. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Schiele sells for world record price at online auction" (in German). Auctionata.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "Auctionata Breaks Online Auction Record: Egon Schiele's Reclining Woman Sold Live for EUR 1.8 Million (US$2.4 Million)". marketwired.com. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

Sources

- Egon Schiele: The Egoist (Egon Schiele: Narcisse écorché, collection « Découvertes Gallimard●Arts » [nº 475]) by Jean-Louis Gaillemin; translated from the French by Liz Nash, "Abrams Discoveries" series & 'New Horizons' series, 2006 (U.S. edition, Harry N. Abrams) / 2007 (UK edition, Thames & Hudson), ISBN 978-0-500-30121-0 & ISBN 0-500-30121-2.

- Egon Schiele: The Complete Works Catalogue Raisonné of all paintings and drawings by Jane Kallir, 1990, Harry N. Abrams, New York, ISBN 0-8109-3802-2.

- Rudolph Leopold: Egon Schiele: Catalogue raisonné. Paintings, Watercolours, Drawings. Revised 2nd edition. Edited by Elisabeth Leopold. Hirmer Publishers (2020). ISBN 978-3-7774-3469-8.

- Diethard Leopold: Egon Schiele. The Great Masters of Art, Hirmer publishers, Munich 2017, ISBN 978-3-7774-2852-9.

- Tobias G. Natter (Ed.), Egon Schiele: The Complete Paintings 1909 – 1918, Taschen, Cologne 2017, ISBN 978-3-8365-4612-6.

- Tobias G. Natter (Ed.), The Self-Portrait: From Schiele to Beckmann., exhibition catalog Neue Galerie New York, Prestel, Munich e.a. 2019, ISBN 978-3-7913-5859-8.

- Kallir, Jane (2003). Egon Schiele: Life and Work. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0810946149.

- Gianni Pozzi, Schiele, 1999, Giunti Editore, Florence, ISBN 978-8-8092-1165-0.

- Sabarsky, S (2000). Egon Schiele Art Centrum Český Krumlov. Egon Schiele Foundation. ISBN 3-928844-32-6.

- Whitford, Frank (1989). Egon Schiele (World of Art). Thames & Hudson; World of Art Ser. ISBN 0500181837.

- Whitford, Frank (1981). Egon Schiele (The World of Art). Oxford University Press; World of Art Ser. ISBN 0195202465.

- Wladika, Michael (2012). Egon Schiele, Bildnis der Mutter des Künstlers (Marie Schiele) mit Pelzkragen. Leopold Museum-Privatstiftung.

Further reading

- David Williams (26 July 2019). "A man found a Egon Schiele drawing in a New York thrift store, and it could be worth a fortune". CNN.

- Smith, Jeffrey K. (25 October 2020). Scoundrels, Cads, and Other Great Artists. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781538126783. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

External links

- Works by or about Egon Schiele at Internet Archive

- "Egon Schiele's birthplace, Tulln"

- "Egon Schiele Museum, Tulln"

- "Leopold Museum, Vienna", Leopold Museum, Vienna, houses the largest collection of Schiele's work. ONLINE COLLECTION

- "Oesterreichische Galerie, Belvedere" The Oesterreichische Galerie, Belvedere, in Vienna contains one of the greatest collections of Schiele's work.

- "Live Flesh" A review of Schiele's work by Arthur Danto in The Nation.

- Neue Galerie for German and Austrian Art (New York)

- Self-portraits by Schiele

- Tracey Emin & Egon Schiele – exhibition at the Leopold Museum Vienna Interview with the co-curator Diethard Leopold