Elkhorn Slough

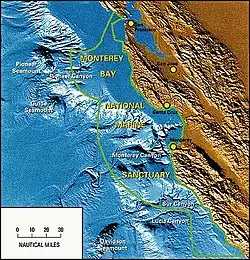

Elkhorn Slough is a 7-mile-long (11 km)[2][3] tidal slough and estuary on Monterey Bay in Monterey County, California. It is California's second largest estuary and the United States' first estuarine sanctuary.[4] The community of Moss Landing and the Moss Landing Power Plant are located at the mouth of the slough on the bay.

| Elkhorn Slough | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of the mouth of Elkhorn Slough on Monterey Bay | |

Location of Elkhorn Slough in California, United States | |

| Location | Moss Landing, Monterey County, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 36°49′00″N 121°46′00″W |

| Operator | Elkhorn Slough Foundation |

| Official name | Elkhorn Slough |

| Designated | 25 June 2018 |

| Reference no. | 2345[1] |

Elkhorn Slough harbors the largest tract of tidal salt marsh in California outside the San Francisco Bay and provides much-needed habitat for hundreds of species of plants and animals, including more than 340 species of birds. It has been designated as a protected Ramsar site since 2018.[1]

History

The name of the slough derives from the native tule elk Cervus canadensis nannodes, now extirpated from the region.[5]

Elkhorn Slough occupies the western reaches of Elkhorn Valley, a relic river valley eroded by drainage pouring out of the Santa Clara Valley and/or Great Valley of California (before the Golden Gate opened) into Monterey Bay during the early Pleistocene. In the mid-1850s A.D. Elkhorn Slough was a minor tributary to the much larger Pajaro-Salinas River system which shared a common entrance to the Pacific Ocean north of Moss Landing. In 1909 winter storms modified the course of the Salinas River to its present location south of Moss Landing, while Elkhorn Slough persisted as a tributary to the Old Salinas River channel. Construction of jetties at the Moss Landing Harbor in 1946 provided a direct link between the Pacific Ocean and Elkhorn Slough. At this time, salt marshes began to retreat from the axis of Elkhorn Slough as it evolved into its present form as a relatively stable estuarine embayment.[4]

Watershed

Carneros Creek is the primary source of freshwater flowing into Elkhorn Slough. McClusky Slough to the north and Moro Cojo Slough to the south also provide freshwater inputs.[6]

Conservation ownership

More than 8,000 acres (3,200 ha) of the watershed's 45,000 acres (18,000 ha) are protected under a mosaic of private and public ownership.

Foundations

The nonprofit Elkhorn Slough Foundation is the single largest land owner in the watershed, with nearly 3,600 acres (1,500 ha). The nonprofit Nature Conservancy was the first to buy Elkhorn Slough property with the goal to protect the area's habitat and wildlife. The Nature Conservancy started with only 60 acres in 1971 and through gifts and purchases of disjointed parcels, gained over 800 acres (320 ha) by September 2012, when it transferred 750 acres (300 ha) to the Elkhorn Slough Foundation. The Foundation already managed conservation on these parcels.[7][8]

Elkhorn Slough State Marine Reserve

The Elkhorn Slough State Marine Reserve (SMR) covers 1.48 square miles (3.8 km2). The SMR protects all marine life within its boundaries. It is managed by the California Department of Fish & Wildlife (CA-DFW) in cooperation with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Fishing and take of all living marine resources is prohibited. It includes the waters below mean high tide within Elkhorn Slough lying:

- east of longitude 121° 46.40’ W. and

- south of latitude 36° 50.50’ N.

Elkhorn Slough State Marine Conservation Area

The Elkhorn Slough State Marine Conservation Area (SMCA) covers 0.09 square miles (0.23 km2). It includes the waters below mean high tide within Elkhorn Slough:

- east of the Highway 1 Bridge and

- west of longitude 121° 46.40’ W.

The SMR and the SMCA were both established in September 2007 by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CA−DFW). It was one of 29 marine protected areas adopted during the first phase of the Marine Life Protection Act Initiative, a collaborative public process to create a statewide network of marine protected areas along the California coastline.[9]

Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve

The Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve is one of 28 National Estuarine Research Reserves established nationwide as field laboratories for scientific research and estuarine education.

Local government

Additional land protected by the Moss Landing Harbor District and the Monterey County Parks Department[8]

Adjacent areas

The Moss Landing Wildlife Area protects the land north and west of the Slough.

The Moro Cojo Slough State Marine Reserve just south of Elkhorn protects a similar wetland area.[9]

Habitat and wildlife

Elkhorn Slough, one of the largest estuaries in California, provides essential habitat for over 700 species, including aquatic mammals, birds, fish, invertebrates, algae and plants. The slough area is home to California's greatest concentration of sea otters, as well as populations of endangered Santa Cruz long-toed salamander and the threatened California red-legged frog.[8] The population of sea otter living in Elkhorn Slough reflect that the species is well-adapted for estuarine habitat, and may be a model for the historical sea otter populations now extinct in San Francisco Bay.

Elkhorn Slough hosts year-round residents tightly associated with estuaries, such as pickleweed, eelgrass, oysters, gaper clams, and longjaw mudsuckers, as well as important seasonal visitors such as migratory shorebirds, sea otters, and sharks and rays. Habitat types include mudflats, tidal creeks and channels.[10] Other vegetative species include such wildflowers as yellow mariposa lily, Calochortus luteus.[11]

Restoration

Conservation groups have worked to remedy indirect harm from human activity in the region in addition to preventing direct damage to the ecosystem by harvest of resources and conversion of land.

Parson's sill

A steel weir was built in 2010 at the mouth of the Parson's Slough, a fork of the Elkhorn. The weir or "sill" is intended to reduce the excess erosion of the marsh caused by the dredging of the Moss Landing Harbor and the redirection of the Salinas River. Primary funding came from a $3.9 million federal stimulus grant.[12] The project was a collaboration among the California Coastal Conservancy, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, DFG, Ducks Unlimited, Elkhorn Slough Foundation, NOAA, URS Corporation, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency[13]

Recreation

Along with hiking and bird watching, kayaking and stand-up paddle boarding are popular activities on the slough. Watching sea otters, sea lions, seals, brown pelicans, American avocets, cormorants, egrets, terns and a host of other wildlife from the water is an experience that provides a unique perspective of how the slough is used by the native inhabitants. People are encouraged to keep at least 100 feet of distance between them and wildlife on the slough.

The Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve and Elkhorn Slough Foundation provide on-site management, education, and stewardship and offer public access via 5 miles (8.0 km) of trails, as well as a Visitor Center and volunteer opportunities.

The nearby Moss Landing Wildlife Area protects 728 acres (295 ha) of salt ponds and salt marsh. Limited recreation is permitted within the Wildlife Area.[16]

Harvest of finfish (by hook-and-line only) and clams are allowed within the conservation area only. Clams may only be taken on the north shore of the slough in the area adjacent to the Moss Landing State Wildlife Area. The California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment has issued a safe advisory for any fish caught in Elkhorn Slough due to elevated levels of mercury and PCBs. In addition, there is a notice of "DO NOT EAT" for leopard sharks and bat rays for women 18–45 years old and children 1–17 years old.[17]

California’s marine protected areas encourage recreational and educational uses of the ocean.[18] Activities such as kayaking, diving, snorkeling, and swimming are allowed unless otherwise restricted.

The Moss Landing Harbor District has jurisdiction over the navigable waterways of Elkhorn Slough and owns Kirby Park at the upper reaches of Elkhorn Slough. Kirby park has a small boat launch and provides parking for a small trail on Nature Conservancy property at the north side. The trail here is fully handicapped-accessible and allows a walk and a wheelchair near the water's edge.[19]

Scientific monitoring

As specified by the Marine Life Protection Act, select marine protected areas along California’s central coast are being monitored by scientists to track their effectiveness and learn more about ocean health. Similar studies in marine protected areas located off of the Santa Barbara Channel Islands have already detected gradual improvements in fish size and number.[20]

References

- "Elkhorn Slough". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data". Archived from the original on 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- "Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve (ESNERR) Final Management Plan". Archived from the original on 2012-06-11. Retrieved 2012-07-17.

- David L. Schwartz; Henry T. Mullins; Daniel F. Belknap (1986). "Holocene Geologic History of a Transform Margin Estuary: Elkhorn Slough, Central California". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 22 (3): 285–302. Bibcode:1986ECSS...22..285S. doi:10.1016/0272-7714(86)90044-2.

- Erwin G. Gudde (1969). California Place Names –The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographic Names. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 100.

- Ryan Bassett (May 2010). Quantifying spatially-explicit change in sediment storage on an emerging floodplain and wetland on Carneros Creek, CA (PDF) (Thesis). California State University Monterey Bay. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2012-09-26.

- "Elkhorn Slough Foundation". Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Jones, Donna (2012-09-18). "Conservation groups team up to preserve Elkhorn Slough diversity". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Elkhorn Slough. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on 2013-06-17. Retrieved 2012-09-18.

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife, "Central Coast Marine Protected Areas Archived 2010-05-20 at the Wayback Machine" . retrieved December 23, 2008.

- Department of Fish and Game. "Appendix O. Regional MPA Management Plans" Archived 2018-06-10 at the Wayback Machine. Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (approved February 2008). Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009. Yellow Mariposa Lily: Calochortus luteus, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg Archived October 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Kuchment, Olga (2009-12-27). "Underwater wall may bring balance to Elkhorn Slough". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2013-02-03. Retrieved 2012-09-18.

- NOAA. "Preserving the 'Life Mud' of a California Estuary". Archived from the original on 2012-06-17. Retrieved 2012-09-18.

- Garlinghouse, Tom (2019-05-11). "$1 million grant for Elkhorn Slough to help restore wetlands". The Mercury News. Archived from the original on 2019-05-13. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Ogasa, Nikk (December 27, 2020). "Elkhorn Slough: Why restoring Hester Marsh is important". Monterey Herald. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- Department of Fish and Game. “Moss Landing Wildlife Area Archived 2010-11-27 at the Wayback Machine”. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- Admin, OEHHA (2016-07-13). "Elkhorn Slough". OEHHA. Archived from the original on 2019-02-23. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- Department of Fish and Game. "California Fish and Game Code section 2853 (b)(3) Archived March 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine". Marine Life Protection Act. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- Archived 2011-04-20 at the Wayback Machine Moss Landing Harbor District

- Castell, Jenn, et al. "How do patterns of abundance and size structure differ between fished and unfished waters in the Channel Islands? Results from SCUBA surveys Archived May 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans (PISCO) at University of California, Santa Barbara and University of California, Santa Cruz; Channel Islands National Park. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

External links

- The official website of the Elkhorn Slough Foundation and Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve

- National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NOAA)

- Elkhorn Slough and Moss Landing

- Marine Life Protection Act Initiative

- The Partnership for Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Oceans (PISCO)