George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

| George V | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Formal portrait, 1923 | |||||

| Reign | 6 May 1910 – 20 January 1936 | ||||

| Coronation | 22 June 1911 | ||||

| Imperial Durbar | 12 December 1911 | ||||

| Predecessor | Edward VII | ||||

| Successor | Edward VIII | ||||

| Born | Prince George of Wales 3 June 1865 Marlborough House, Westminster, Middlesex, England | ||||

| Died | 20 January 1936 (aged 70) Sandringham House, Norfolk, England | ||||

| Burial | 28 January 1936 Royal Vault, St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle 27 February 1939North Nave Aisle, St George's Chapel | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue Detail | |||||

| |||||

| House |

| ||||

| Father | Edward VII | ||||

| Mother | Alexandra of Denmark | ||||

| Religion | Protestant | ||||

| Signature | |||||

| Military career | |||||

| Service | Royal Navy | ||||

| Years of active service | 1877–1892 | ||||

| Rank | Full list | ||||

| Commands held | |||||

Born during the reign of his grandmother Queen Victoria, George was the second son of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra), and third in the line of succession to the British throne behind his father and his elder brother, Prince Albert Victor. From 1877 to 1892, George served in the Royal Navy, until his elder brother's unexpected death in January 1892 put him directly in line for the throne. George married his brother's fiancée, Princess Victoria Mary of Teck, the next year, and they had six children. When Queen Victoria died in 1901, George's father ascended the throne as Edward VII, and George was created Prince of Wales. He became king-emperor on his father's death in 1910.

George's reign saw the rise of socialism, communism, fascism, Irish republicanism, and the Indian independence movement, all of which radically changed the political landscape of the British Empire, which itself reached its territorial peak by the beginning of the 1920s. The Parliament Act 1911 established the supremacy of the elected British House of Commons over the unelected House of Lords. As a result of the First World War (1914–1918), the empires of his first cousins Nicholas II of Russia and Wilhelm II of Germany fell, while the British Empire expanded to its greatest effective extent. In 1917, George became the first monarch of the House of Windsor, which he renamed from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha as a result of anti-German public sentiment. He appointed the first Labour ministry in 1924, and the 1931 Statute of Westminster recognised the Empire's dominions as separate, independent states within the British Commonwealth of Nations.

George suffered from smoking-related health problems during his later reign. On his death in January 1936, he was succeeded by his eldest son, Edward VIII. Edward abdicated in December of that year and was succeeded by his younger brother Albert, who took the regnal name George VI.

Early life and education

George was born on 3 June 1865, in Marlborough House, London. He was the second son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, and Alexandra, Princess of Wales. His father was the eldest son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, and his mother was the eldest daughter of King Christian IX and Queen Louise of Denmark. He was baptised at Windsor Castle on 7 July 1865 by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Longley.[lower-alpha 1]

As a younger son of the Prince of Wales, there was little expectation that George would become king. He was third in line to the throne, after his father, and elder brother, Prince Albert Victor. George was only 17 months younger than Albert Victor, and the two princes were educated together. John Neale Dalton was appointed as their tutor in 1871. Neither Albert Victor nor George excelled intellectually.[2] As their father thought that the navy was "the very best possible training for any boy",[3] in September 1877, when George was 12 years old, both brothers joined the cadet training ship HMS Britannia at Dartmouth, Devon.[4]

For three years from 1879, the princes served on HMS Bacchante, accompanied by Dalton. They toured the colonies of the British Empire in the Caribbean, South Africa and Australia, and visited Norfolk, Virginia, as well as South America, the Mediterranean, Egypt, and East Asia. In 1881 on a visit to Japan, George had a local artist tattoo a blue and red dragon on his arm,[5] and was received in an audience by the Emperor Meiji; George and his brother presented Empress Haruko with two wallabies from Australia.[6] Dalton wrote an account of their journey entitled The Cruise of HMS Bacchante.[7] Between Melbourne and Sydney, Dalton recorded a sighting of the Flying Dutchman, a mythical ghost ship.[8] When they returned to Britain, the Queen complained that her grandsons could not speak French or German, and so they spent six months in Lausanne in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to learn another language.[9] After Lausanne, the brothers were separated; Albert Victor attended Trinity College, Cambridge, while George continued in the Royal Navy. He travelled the world, visiting many areas of the British Empire. During his naval career he commanded Torpedo Boat 79 in home waters, then HMS Thrush on the North America and West Indies Station. His last active service was in command of HMS Melampus in 1891–1892. From then on, his naval rank was largely honorary.[10]

Marriage

As a young man destined to serve in the navy, Prince George served for many years under the command of his uncle Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, who was stationed in Malta. There, he grew close to and fell in love with his cousin Princess Marie of Edinburgh. His grandmother, father and uncle all approved the match, but his own mother and Marie's mother opposed it. The Princess of Wales thought the family was too pro-German, and the Duchess of Edinburgh disliked England. The Duchess, the only daughter of Alexander II of Russia, resented the fact that, as the wife of a younger son of the British sovereign, she had to yield precedence to George's mother, the Princess of Wales, whose father had been a minor German prince before being called unexpectedly to the throne of Denmark. Guided by her mother, Marie refused George when he proposed to her. She married Ferdinand, the future king of Romania, in 1893.[11]

In November 1891, George's elder brother, Albert Victor, became engaged to his second cousin once removed Princess Victoria Mary of Teck, known as "May" within the family.[12] Her parents were Francis, Duke of Teck (a member of a morganatic, cadet branch of the House of Württemberg), and Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, a male-line granddaughter of George III and a first cousin of Queen Victoria.[13]

On 14 January 1892, six weeks after the formal engagement, Albert Victor died of pneumonia during an influenza pandemic, leaving George second in line to the throne, and likely to succeed after his father. George had only just recovered from a serious illness himself, having been confined to bed for six weeks with typhoid fever, the disease that was thought to have killed his grandfather Prince Albert.[14] Queen Victoria still regarded Princess May as a suitable match for her grandson, and George and May grew close during their shared period of mourning.[15]

A year after Albert Victor's death, George proposed to May and was accepted. They married on 6 July 1893 at the Chapel Royal in St James's Palace, London. Throughout their lives, they remained devoted to each other. George was, on his own admission, unable to express his feelings easily in speech, but they often exchanged loving letters and notes of endearment.[16]

Duke of York

The death of his elder brother effectively ended George's naval career, as he was now second in line to the throne, after his father.[17] George was created Duke of York, Earl of Inverness, and Baron Killarney by Queen Victoria on 24 May 1892,[18] and received lessons in constitutional history from J. R. Tanner.[19]

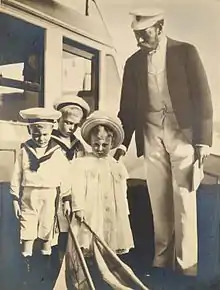

The Duke and Duchess of York had five sons and a daughter. Randolph Churchill claimed that George was a strict father, to the extent that his children were terrified of him, and that George had remarked to the Earl of Derby: "My father was frightened of his mother, I was frightened of my father, and I am damned well going to see to it that my children are frightened of me." In reality, there is no direct source for the quotation and it is likely that George's parenting style was little different from that adopted by most people at the time.[20] Whether this was the case or not, his children did seem to resent his strict nature, his son Prince Henry going as far as to describe him as a "terrible father" in later years.[21]

They lived mainly at York Cottage,[22] a relatively small house in Sandringham, Norfolk, where their way of life mirrored that of a comfortable middle-class family rather than royalty.[23] George preferred a simple, almost quiet, life, in marked contrast to the lively social life pursued by his father. His official biographer, Harold Nicolson, later despaired of George's time as Duke of York, writing: "He may be all right as a young midshipman and a wise old king, but when he was Duke of York ... he did nothing at all but kill [i.e. shoot] animals and stick in stamps."[24] George was an avid stamp collector, which Nicolson disparaged,[25] but George played a large role in building the Royal Philatelic Collection into the most comprehensive collection of United Kingdom and Commonwealth stamps in the world, in some cases setting record purchase prices for items.[26]

In October 1894, George's maternal uncle-by-marriage, Alexander III of Russia, died. At the request of his father, "out of respect for poor dear Uncle Sasha's memory", George joined his parents in Saint Petersburg for the funeral.[27] He and his parents remained in Russia for the wedding a week later of the new Russian emperor, his maternal first cousin Nicholas II, to one of George's paternal first cousins, Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, who had once been considered as a potential bride for George's elder brother.[28]

Prince of Wales

As Duke of York, George carried out a wide variety of public duties. On the death of Queen Victoria on 22 January 1901, George's father ascended the throne as King Edward VII.[29] George inherited the title of Duke of Cornwall, and for much of the rest of that year, he was known as the Duke of Cornwall and York.[30]

In 1901, the Duke and Duchess toured the British Empire. Their tour included Gibraltar, Malta, Port Said, Aden, Ceylon, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Mauritius, South Africa, Canada, and the Colony of Newfoundland. The tour was designed by Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain with the support of Prime Minister Lord Salisbury to reward the Dominions for their participation in the South African War of 1899–1902. George presented thousands of specially designed South African War medals to colonial troops. In South Africa, the royal party met civic leaders, African leaders, and Boer prisoners, and was greeted by elaborate decorations, expensive gifts, and fireworks displays. Despite this, not all residents responded favourably to the tour. Many white Cape Afrikaners resented the display and expense, the war having weakened their capacity to reconcile their Afrikaner-Dutch culture with their status as British subjects. Critics in the English-language press decried the enormous cost at a time when families faced severe hardship.[31]

In Australia, George opened the first session of the Australian Parliament on the creation of the Commonwealth of Australia.[32] In New Zealand, he praised the military values, bravery, loyalty, and obedience to duty of New Zealanders, and the tour gave New Zealand a chance to show off its progress, especially in its adoption of up-to-date British standards in communications and the processing industries. The implicit goal was to advertise New Zealand's attractiveness to tourists and potential immigrants, while avoiding news of growing social tensions, by focusing the attention of the British press on a land few knew about.[33] On his return to Britain, in a speech at Guildhall, London, George warned of "the impression which seemed to prevail among [our] brethren across the seas, that the Old Country must wake up if she intends to maintain her old position of pre-eminence in her colonial trade against foreign competitors."[34]

On 9 November 1901, George was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester.[35][36] King Edward wished to prepare his son for his future role as king. In contrast to Edward himself, whom Queen Victoria had deliberately excluded from state affairs, George was given wide access to state documents by his father.[17][37] George in turn allowed his wife access to his papers,[38] as he valued her counsel and she often helped write her husband's speeches.[39] As Prince of Wales, he supported reforms in naval training, including cadets being enrolled at the ages of twelve and thirteen, and receiving the same education, whatever their class and eventual assignments. The reforms were implemented by the then Second (later First) Sea Lord, Sir John Fisher.[40]

From November 1905 to March 1906, George and May toured British India, where he was disgusted by racial discrimination and campaigned for greater involvement of Indians in the government of the country.[41] The tour was almost immediately followed by a trip to Spain for the wedding of King Alfonso XIII to George's first cousin Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg, at which the bride and groom narrowly avoided assassination when the driver of their coach and more than a dozen spectators were killed by a bomb thrown by an anarchist, Mateu Morral. A week after returning to Britain, George and May travelled to Norway for the coronation of King Haakon VII, George's cousin and brother-in-law, and Queen Maud, George's sister.[42]

Reign

On 6 May 1910, Edward VII died, and George became king. He wrote in his diary,

I have lost my best friend and the best of fathers ... I never had a [cross] word with him in my life. I am heart-broken and overwhelmed with grief but God will help me in my responsibilities and darling May will be my comfort as she has always been. May God give me strength and guidance in the heavy task which has fallen on me.[43]

George had never liked his wife's habit of signing official documents and letters as "Victoria Mary" and insisted she drop one of those names. They both thought she should not be called Queen Victoria, and so she became Queen Mary.[44] Later that year, a radical propagandist, Edward Mylius, published a lie that George had secretly married in Malta as a young man, and that consequently his marriage to Queen Mary was bigamous. The lie had first surfaced in print in 1893, but George had shrugged it off as a joke. In an effort to kill off rumours, Mylius was arrested, tried and found guilty of criminal libel, and was sentenced to a year in prison.[45]

George objected to the anti-Catholic wording of the Accession Declaration that he would be required to make at the opening of his first parliament. He made it known that he would refuse to open parliament unless it was changed. As a result, the Accession Declaration Act 1910 shortened the declaration and removed the most offensive phrases.[46]

George and Mary's coronation took place at Westminster Abbey on 22 June 1911,[17] and was celebrated by the Festival of Empire in London. In July, the King and Queen visited Ireland for five days; they received a warm welcome, with thousands of people lining the route of their procession to cheer.[47][48] Later in 1911, the King and Queen travelled to India for the Delhi Durbar, where they were presented to an assembled audience of Indian dignitaries and princes as the Emperor and Empress of India on 12 December 1911. George wore the newly created Imperial Crown of India at the ceremony, and declared the shifting of the Indian capital from Calcutta to Delhi. He was the only Emperor of India to be present at his own Delhi Durbar. As he and Mary travelled throughout the subcontinent, George took the opportunity to indulge in big game hunting in Nepal, shooting 21 tigers, 8 rhinoceroses and a bear over 10 days.[49] He was a keen and expert marksman.[50] On a later occasion, on 18 December 1913, he shot over a thousand pheasants in six hours (about one bird every 20 seconds) while visiting the home of Lord Burnham. Even George had to acknowledge that "we went a little too far" that day.[51]

National politics

George inherited the throne at a politically turbulent time.[52] Lloyd George's People's Budget had been rejected the previous year by the Conservative and Unionist-dominated House of Lords, contrary to the normal convention that the Lords did not veto money bills.[53] Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith had asked the previous king to give an undertaking that he would create sufficient Liberal peers to allow the passage of Liberal legislation. Edward had reluctantly agreed, provided the Lords rejected the budget after two successive general elections. After the January 1910 general election, the Conservative peers allowed the budget, for which the government now had an electoral mandate, to pass without a vote.[54]

Asquith attempted to curtail the power of the Lords through constitutional reforms, which were again blocked by the Upper House. A constitutional conference on the reforms broke down in November 1910 after 21 meetings. Asquith and Lord Crewe, Liberal leader in the Lords, asked George to grant a dissolution, leading to a second general election, and to promise to create sufficient Liberal peers if the Lords blocked the legislation again.[55] If George refused, the Liberal government would otherwise resign, which would have given the appearance that the monarch was taking sides – with "the peers against the people" – in party politics.[56] The King's two private secretaries, the Liberal Lord Knollys and the Unionist Lord Stamfordham, gave George conflicting advice.[57][58] Knollys advised George to accept the Cabinet's demands, while Stamfordham advised George to accept the resignation.[57] Like his father, George reluctantly agreed to the dissolution and creation of peers, although he felt his ministers had taken advantage of his inexperience to browbeat him.[59] After the December 1910 general election, the Lords let the bill pass on hearing of the threat to swamp the house with new peers.[60] The subsequent Parliament Act 1911 permanently removed – with a few exceptions – the power of the Lords to veto bills. George later came to feel that Knollys had withheld information from him about the willingness of the opposition to form a government if the Liberals had resigned.[61]

The 1910 general elections had left the Liberals as a minority government dependent upon the support of the Irish Nationalist Party. As desired by the Nationalists, Asquith introduced legislation that would give Ireland Home Rule, but the Conservatives and Unionists opposed it.[17][62] As tempers rose over the Home Rule Bill, which would never have been possible without the Parliament Act, relations between the elderly Knollys and the Conservatives became poor, and he was pushed into retirement.[63] Desperate to avoid the prospect of civil war in Ireland between Unionists and Nationalists, George called a meeting of all parties at Buckingham Palace in July 1914 in an attempt to negotiate a settlement.[64] After four days the conference ended without an agreement.[17][65] Political developments in Britain and Ireland were overtaken by events in Europe, and the issue of Irish Home Rule was suspended for the duration of the war.[17][66]

First World War

On 4 August 1914, George wrote in his diary, "I held a council at 10:45 to declare war with Germany. It is a terrible catastrophe but it is not our fault. ... Please to God it may soon be over."[67] From 1914 to 1918, Britain and its allies were at war with the Central Powers, led by the German Empire. The German Kaiser Wilhelm II, who for the British public came to symbolise all the horrors of the war, was the King's first cousin. George's paternal grandfather was Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha; consequently, the King and his children bore the German titles Prince and Princess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Duke and Duchess of Saxony. Queen Mary, although born in England like her mother, was the daughter of the Duke of Teck, a descendant of the German Dukes of Württemberg. George had brothers-in-law and cousins who were British subjects but who bore German titles such as Duke and Duchess of Teck, Prince and Princess of Battenberg, and Prince and Princess of Schleswig-Holstein. When H. G. Wells wrote about Britain's "alien and uninspiring court", George replied: "I may be uninspiring, but I'll be damned if I'm alien."[68]

On 17 July 1917, George appeased British nationalist feelings by issuing a royal proclamation that changed the name of the British royal house from the German-sounding House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha to the House of Windsor.[69] He and all his British relatives relinquished their German titles and styles and adopted British-sounding surnames. George compensated his male relatives by giving them British peerages. His cousin Prince Louis of Battenberg, who earlier in the war had been forced to resign as First Sea Lord through anti-German feeling, became Louis Mountbatten, 1st Marquess of Milford Haven, while Queen Mary's brothers became Adolphus Cambridge, 1st Marquess of Cambridge, and Alexander Cambridge, 1st Earl of Athlone.[70]

In letters patent gazetted on 11 December 1917, the King restricted the style of "Royal Highness" and the titular dignity of "Prince (or Princess) of Great Britain and Ireland" to the children of the Sovereign, the children of the sons of the Sovereign and the eldest living son of the eldest son of a Prince of Wales.[71] The letters patent also stated that "the titles of Royal Highness, Highness or Serene Highness, and the titular dignity of Prince and Princess shall cease except those titles already granted and remaining unrevoked". George's relatives who fought on the German side, such as Ernest Augustus, Crown Prince of Hanover, and Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, had their British peerages suspended by a 1919 Order in Council under the provisions of the Titles Deprivation Act 1917. Under pressure from his mother, George also removed the Garter flags of his German relations from St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[72]

When Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, George's first cousin, was overthrown in the Russian Revolution of 1917, the British government offered political asylum to the Tsar and his family, but worsening conditions for the British people, and fears that revolution might come to the British Isles, led George to think that the presence of the Romanovs would be seen as inappropriate.[73] Despite the later claims of Lord Mountbatten of Burma that Prime Minister David Lloyd George was opposed to the rescue of the Russian imperial family, the letters of Lord Stamfordham suggest that it was George V who opposed the idea against the advice of the government.[74] Advance planning for a rescue was undertaken by MI1, a branch of the British secret service,[75] but because of the strengthening position of the Bolshevik revolutionaries and wider difficulties with the conduct of the war, the plan was never put into operation.[76] Nicholas and his immediate family remained in Russia, where they were killed by the Bolsheviks in 1918. George wrote in his diary: "It was a foul murder. I was devoted to Nicky, who was the kindest of men and thorough gentleman: loved his country and people."[77] The following year, Nicholas's mother, Marie Feodorovna, and other members of the extended Russian imperial family were rescued from Crimea by a British warship.[78]

Two months after the end of the war, the King's youngest son, John, died aged 13 after a lifetime of ill health. George was informed of his death by Queen Mary, who wrote, "[John] had been a great anxiety to us for many years ... The first break in the family circle is hard to bear but people have been so kind & sympathetic & this has helped us much."[79]

In May 1922, George toured Belgium and northern France, visiting the First World War cemeteries and memorials being constructed by the Imperial War Graves Commission. The event was described in a poem, The King's Pilgrimage by Rudyard Kipling.[80] The tour, and one short visit to Italy in 1923, were the only times George agreed to leave the United Kingdom on official business after the end of the war.[81]

Post-war reign

Before the First World War, most of Europe was ruled by monarchs related to George, but during and after the war, the monarchies of Austria, Germany, Greece, and Spain, like Russia, fell to revolution and war. In March 1919, Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Lisle Strutt was dispatched on the personal authority of the King to escort the former Emperor Charles I of Austria and his family to safety in Switzerland.[83] In 1922, a Royal Navy ship was sent to Greece to rescue his cousins Prince and Princess Andrew.[84]

Political turmoil in Ireland continued as the Nationalists fought for independence; George expressed his horror at government-sanctioned killings and reprisals to Prime Minister Lloyd George.[85] At the opening session of the Parliament of Northern Ireland on 22 June 1921, the King appealed for conciliation in a speech part drafted by General Jan Smuts and approved by Lloyd George.[86] A few weeks later, a truce was agreed.[87] Negotiations between Britain and the Irish secessionists led to the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty.[88] By the end of 1922, Ireland was partitioned, the Irish Free State was established, and Lloyd George was out of office.[89]

George and his advisers were concerned about the rise of socialism and the growing labour movement, which they mistakenly associated with republicanism. The socialists no longer believed in their anti-monarchical slogans and were ready to come to terms with the monarchy if it took the first step. George adopted a more democratic, inclusive stance that crossed class lines and brought the monarchy closer to the public and the working class—a dramatic change for the King, who was most comfortable with naval officers and landed gentry. He cultivated friendly relations with moderate Labour Party politicians and trade union officials. His abandonment of social aloofness conditioned the royal family's behaviour and enhanced its popularity during the economic crises of the 1920s and for over two generations thereafter.[90][91]

The years between 1922 and 1929 saw frequent changes in government. In 1924, George appointed the first Labour Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, in the absence of a clear majority for any one of the three major parties. George's tact in appointing the first Labour government (which lasted less than a year) allayed the suspicions of the party's sympathisers that he would work against their interests. During the General Strike of 1926, George advised the government of Conservative Stanley Baldwin against taking inflammatory action,[92] and took exception to suggestions that the strikers were "revolutionaries" saying, "Try living on their wages before you judge them."[93]

In 1926, George hosted an Imperial Conference in London at which the Balfour Declaration accepted the growth of the British Dominions into self-governing "autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another". The Statute of Westminster 1931 formalised the Dominions' legislative independence[94] and established that the succession to the throne could not be changed unless all the Parliaments of the Dominions as well as the Parliament at Westminster agreed.[17] The Statute's preamble described the monarch as "the symbol of the free association of the members of the British Commonwealth of Nations", who were "united by a common allegiance".[95]

In the wake of a world financial crisis, George encouraged the formation of a National Government in 1931 led by MacDonald and Baldwin,[96][lower-alpha 2] and volunteered to reduce the civil list to help balance the budget.[96] He was concerned by the rise to power in Germany of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party.[99] In 1934, George bluntly told the German ambassador Leopold von Hoesch that Germany was now the peril of the world, and that there was bound to be a war within ten years if Germany went on at the present rate; he warned the British ambassador in Berlin, Eric Phipps, to be suspicious of the Nazis.[100]

.jpg.webp)

In 1932, George agreed to deliver a Royal Christmas speech on the radio, an event that became annual thereafter. He was not in favour of the innovation originally but was persuaded by the argument that it was what his people wanted.[101] By the Silver Jubilee of his reign in 1935, he had become a well-loved king, saying in response to the crowd's adulation, "I cannot understand it, after all I am only a very ordinary sort of fellow."[102]

George's relationship with his eldest son and heir, Edward, deteriorated in these later years. George was disappointed in Edward's failure to settle down in life and appalled by his many affairs with married women.[17] In contrast, he was fond of his second son, Prince Albert (later George VI), and doted on his eldest granddaughter, Princess Elizabeth; he nicknamed her "Lilibet", and she affectionately called him "Grandpa England".[103] In 1935, George said of his son Edward: "After I am dead, the boy will ruin himself within 12 months", and of Albert and Elizabeth: "I pray to God my eldest son will never marry and have children, and that nothing will come between Bertie and Lilibet and the throne".[104][105]

Declining health and death

The First World War took a toll on George's health: he was seriously injured on 28 October 1915 when thrown by his horse at a troop review in France,[106] and his heavy smoking exacerbated recurring breathing problems. He suffered from chronic bronchitis. In 1925, on the instruction of his doctors, he was reluctantly sent on a recuperative private cruise in the Mediterranean; it was his third trip abroad since the war, and his last.[107] In November 1928, he fell seriously ill with septicaemia, which localised between the base of his right lung and diaphragm in the form of an empyema that required drainage.[108] For the next two years his son Edward took over many of his duties.[109] In 1929, the suggestion of a further rest abroad was rejected by the King "in rather strong language".[110] Instead, he retired for three months to Craigweil House, Aldwick, in the seaside resort of Bognor, Sussex.[111] As a result of his stay, the town acquired the suffix Regis – Latin for "of the King". A myth later grew that his last words, on being told that he would soon be well enough to revisit the town, were "Bugger Bognor!"[112][113][114]

George never fully recovered. In his final year, he was occasionally administered oxygen.[115] The death of his favourite sister, Victoria, in December 1935 depressed him deeply. On the evening of 15 January 1936, George took to his bedroom at Sandringham House complaining of a cold; he remained in the room until his death.[116] He became gradually weaker, drifting in and out of consciousness. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin later said:

... each time he became conscious it was some kind inquiry or kind observation of someone, some words of gratitude for kindness shown. But he did say to his secretary when he sent for him: "How is the Empire?" An unusual phrase in that form, and the secretary said: "All is well, sir, with the Empire", and the King gave him a smile and relapsed once more into unconsciousness.[117]

By 20 January, George was close to death. His physicians, led by Lord Dawson of Penn, issued a bulletin with the words "The King's life is moving peacefully towards its close."[118][119] Dawson's private diary, unearthed after his death and made public in 1986, reveals that George's last words, a mumbled "God damn you!",[120] were addressed to his nurse, Catherine Black, when she gave him a sedative that night. Dawson, who supported the "gentle growth of euthanasia",[121] admitted in the diary that he ended the King's life:[120][122][123]

At about 11 o'clock it was evident that the last stage might endure for many hours, unknown to the Patient but little comporting with that dignity and serenity which he so richly merited and which demanded a brief final scene. Hours of waiting just for the mechanical end when all that is really life has departed only exhausts the onlookers & keeps them so strained that they cannot avail themselves of the solace of thought, communion or prayer. I therefore decided to determine the end and injected (myself) morphia gr.3/4 [grains] and shortly afterwards cocaine gr.1 [grains] into the distended jugular vein ... In about 1/4 an hour – breathing quieter – appearance more placid – physical struggle gone.[123]

Dawson wrote that he acted to preserve the King's dignity, to prevent further strain on the family, and so that George's death at 11:55 pm could be announced in the morning edition of The Times newspaper rather than "less appropriate ... evening journals".[120][122] Neither Queen Mary, who was intensely religious and might not have sanctioned euthanasia, nor the Prince of Wales was consulted. The royal family did not want the King to endure pain and suffering and did not want his life prolonged artificially but neither did they approve Dawson's actions.[124] British Pathé announced the King's death the following day, in which he was described as "for each one of us, more than a King, a father of a great family".[125]

The German composer Paul Hindemith went to a BBC studio on the morning after the King's death and in six hours wrote Trauermusik ("Mourning Music"), for viola and orchestra. It was performed that same evening in a live broadcast by the BBC, with Adrian Boult conducting the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the composer as soloist.[126] At the procession to George's lying in state in Westminster Hall, the cross surmounting the Imperial State Crown atop George's coffin fell off and landed in the gutter as the cortège turned into New Palace Yard. George's eldest son and successor, Edward VIII, saw it fall and wondered whether it was a bad omen for his new reign.[127] As a mark of respect to their father, George's four surviving sons – Edward, Albert, Henry, and George – mounted the guard, known as the Vigil of the Princes, at the catafalque on the night before the funeral.[128] The vigil was not repeated until the death of George's daughter-in-law, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, in 2002. George V was interred at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, on 28 January 1936.[129] Edward abdicated before the year was out, leaving Albert to ascend the throne as George VI.[130]

Legacy

George V disliked sitting for portraits[17] and despised modern art; he was so displeased by one portrait by Charles Sims that he ordered it to be burned.[131] He did admire sculptor Bertram Mackennal, who created statues of George for display in Madras and Delhi, and William Reid Dick, whose statue of George V stands outside Westminster Abbey, London.[17]

Although he and his wife occasionally toured the British Empire, George preferred to stay at home pursuing his hobbies of stamp collecting and game shooting and lived a life that later biographers would consider dull because of its conventionality.[132] He was not an intellectual: on returning from one evening at the opera he wrote, "Went to Covent Garden and saw Fidelio and damned dull it was."[133] He was earnestly devoted to Britain and its Empire.[134] He explained, "it has always been my dream to identify myself with the great idea of Empire."[135] He appeared hard-working and became widely admired by the people of Britain and the Empire, as well as "the Establishment".[136] In the words of historian David Cannadine, King George V and Queen Mary were an "inseparably devoted couple" who upheld "character" and "family values".[137]

George established a standard of conduct for British royalty that reflected the values and virtues of the upper middle-class rather than upper-class lifestyles or vices.[138] Acting within his constitutional bounds, he dealt skilfully with a succession of crises: Ireland, the First World War, and the first socialist minority government in Britain.[17] He was by temperament a traditionalist who never fully appreciated or approved the revolutionary changes under way in British society.[139] Nevertheless, he invariably wielded his influence as a force of neutrality and moderation, seeing his role as mediator rather than final decision maker.[140]

Titles, honours and arms

As Duke of York, George's arms were the royal arms, with an inescutcheon of the arms of Saxony, all differenced with a label of three points argent, the centre point bearing an anchor azure. The anchor was removed from his coat of arms as the Prince of Wales. As King, he bore the royal arms. In 1917, he removed, by warrant, the Saxony inescutcheon from the arms of all male-line descendants of the Prince Consort domiciled in the United Kingdom (although the royal arms themselves had never borne the shield).[141]

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Marriage | Their children | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Spouse | |||||

| Edward VIII (later Duke of Windsor) |

23 June 1894 | 28 May 1972 (aged 77) | 3 June 1937 | Wallis Simpson | None | |

| George VI | 14 December 1895 | 6 February 1952 (aged 56) | 26 April 1923 | Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon | Elizabeth II | |

| Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon | ||||||

| Mary, Princess Royal | 25 April 1897 | 28 March 1965 (aged 67) | 28 February 1922 | Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood | George Lascelles, 7th Earl of Harewood | |

| The Hon. Gerald Lascelles | ||||||

| Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester | 31 March 1900 | 10 June 1974 (aged 74) | 6 November 1935 | Lady Alice Montagu Douglas Scott | Prince William of Gloucester | |

| Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester | ||||||

| Prince George, Duke of Kent | 20 December 1902 | 25 August 1942 (aged 39) | 29 November 1934 | Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark | Prince Edward, Duke of Kent | |

| Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy | ||||||

| Prince Michael of Kent | ||||||

| Prince John | 12 July 1905 | 18 January 1919 (aged 13) | None | None | ||

Ancestry

See also

Notes

- His godparents were the King of Hanover (Queen Victoria's cousin, for whom Prince Edward of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach stood proxy); the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Prince Albert's brother, for whom the Lord President of the Council, Earl Granville, stood proxy); the Prince of Leiningen (the Prince of Wales's half-cousin); the Crown Prince of Denmark (the Princess of Wales's brother, for whom the Lord Chamberlain, Viscount Sydney, stood proxy); the Queen of Denmark (George's maternal grandmother, for whom Queen Victoria stood proxy); the Duke of Cambridge (Queen Victoria's cousin); the Duchess of Cambridge (Queen Victoria's aunt, for whom George's aunt Princess Helena stood proxy); and Princess Louis of Hesse and by Rhine (George's aunt, for whom her sister Princess Louise stood proxy).[1]

- Vernon Bogdanor argues that George V played a crucial and active role in the political crisis of August–October 1931, and was a determining influence on Prime Minister MacDonald.[97] Philip Williamson disputes Bogdanor, saying the idea of a national government had been in the minds of party leaders since late 1930 and it was they, not the King, who determined when the time had come to establish one.[98]

References

- The Times (London), Saturday, 8 July 1865, p. 12.

- Clay, p. 39; Sinclair, pp. 46–47

- Sinclair, pp. 49–50

- Clay, p. 71; Rose, p. 7

- Rose, p. 13

- Keene, Donald (2002), Emperor of Japan: Meiji and his world, 1852–1912, Columbia University Press, pp. 350–351

- Rose, p. 14; Sinclair, p. 55

- Rose, p. 11

- Clay, p. 92; Rose, pp. 15–16

- Sinclair, p. 69

- Pope-Hennessy, pp. 250–251

- Rose, pp. 22–23

- Rose, p. 29

- Rose, pp. 20–21, 24

- Pope-Hennessy, pp. 230–231

- Sinclair, p. 178

- Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004; online edition May 2009), "George V (1865–1936)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33369, retrieved 1 May 2010 (Subscription required)

- Clay, p. 149

- Clay, p. 150; Rose, p. 35

- Rose, pp. 53–57; Sinclair, p. 93 ff

- Vickers, ch. 18

- Renamed from Bachelor's Cottage

- Clay, p. 154; Nicolson, p. 51; Rose, p. 97

- Harold Nicolson's diary quoted in Sinclair, p. 107

- Nicolson's Comments 1944–1948, quoted in Rose, p. 42

- The Royal Philatelic Collection, Official website of the British Monarchy, archived from the original on 15 April 2012, retrieved 1 May 2010

- Clay, p. 167

- Rose, pp. 22, 208–209

- Rose, p. 42

- Rose, pp. 44–45

- Buckner, Phillip (November 1999), "The Royal Tour of 1901 and the Construction of an Imperial Identity in South Africa", South African Historical Journal, 41: 324–348, doi:10.1080/02582479908671897

- Rose, pp. 43–44

- Bassett, Judith (1987), "'A Thousand Miles of Loyalty': the Royal Tour of 1901", New Zealand Journal of History, 21 (1): 125–138; Oliver, W. H., ed. (1981), The Oxford History of New Zealand, pp. 206–208

- Rose, p. 45

- "No. 27375", The London Gazette, 9 November 1901, p. 7289

- Previous Princes of Wales, Household of HRH The Prince of Wales, archived from the original on 19 April 2020, retrieved 19 March 2018

- Clay, p. 244; Rose, p. 52

- Rose, p. 289

- Sinclair, p. 107

- Massie, Robert K. (1991), Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War, Random House, pp. 449–450

- Rose, pp. 61–66

- Rose, pp. 67–68

- King George V's diary, 6 May 1910, Royal Archives, quoted in Rose, p. 75

- Pope-Hennessy, p. 421; Rose, pp. 75–76

- Rose, pp. 82–84

- Wolffe, John (2010), "Protestantism, Monarchy and the Defence of Christian Britain 1837–2005", in Brown, Callum G.; Snape, Michael F. (eds.), Secularisation in the Christian World, Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing, pp. 63–64, ISBN 978-0-7546-9930-9, archived from the original on 17 June 2016, retrieved 28 November 2015

- Rayner, Gordon (10 November 2010), "How George V was received by the Irish in 1911", The Telegraph, archived from the original on 18 April 2018

- "The queen in 2011 ... the king in 1911", the Irish Examiner, 11 May 2011, archived from the original on 13 August 2014, retrieved 13 August 2014

- Rose, p. 136

- Rose, pp. 39–40

- Rose, p. 87; Windsor, pp. 86–87

- Rose, p. 115

- Rose, pp. 112–114

- Rose, p. 114

- Rose, pp. 116–121

- Rose, pp. 121–122

- Rose, pp. 120, 141

- Hardy, Frank (May 1970), "The King and the constitutional crisis", History Today, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 338–347

- Rose, pp. 121–125

- Rose, pp. 125–130

- Rose, p. 123

- Rose, p. 137

- Rose, pp. 141–143

- Rose, pp. 152–153, 156–157

- Rose, p. 157

- Rose, p. 158

- Nicolson, p. 247

- Nicolson, p. 308

- "No. 30186", The London Gazette, 17 July 1917, p. 7119

- Rose, pp. 174–175

- Nicolson, p. 310

- Clay, p. 326; Rose, p. 173

- Nicolson, p. 301; Rose, pp. 210–215; Sinclair, p. 148

- Rose, p. 210

- Crossland, John (15 October 2006), "British spies in plot to save Tsar", The Sunday Times

- Sinclair, p. 149

- Diary, 25 July 1918, quoted in Clay, p. 344 and Rose, p. 216

- Clay, pp. 355–356

- Pope-Hennessy, p. 511

- Pinney, Thomas, ed. (1990), The Letters of Rudyard Kipling 1920–30, vol. 5, University of Iowa Press, note 1, p. 120, ISBN 978-0-87745-898-2

- Rose, p. 294

- Rein Taagepera (September 1997), "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia", International Studies Quarterly, 41 (3): 475–504, doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053, JSTOR 2600793, archived from the original on 19 November 2018, retrieved 28 December 2018

- "Archduke Otto von Habsburg", The Daily Telegraph (obituary), London, UK, 4 July 2011, archived from the original on 24 December 2019, retrieved 4 April 2018

- Rose, pp. 347–348

- Nicolson, p. 347; Rose, pp. 238–241; Sinclair, p. 114

- Mowat, p. 84

- Mowat, p. 86

- Mowat, pp. 89–93

- Mowat, pp. 106–107, 119

- Prochaska, Frank (1999), "George V and Republicanism, 1917–1919", Twentieth Century British History, 10 (1): 27–51, doi:10.1093/tcbh/10.1.27

- Kirk, Neville (2005), "The Conditions of Royal Rule: Australian and British Socialist and Labour Attitudes to the Monarchy, 1901–11", Social History, 30 (1): 64–88, doi:10.1080/0307102042000337297, S2CID 144979227

- Nicolson, p. 419; Rose, pp. 341–342

- Rose, p. 340; Sinclair, p. 105

- Rose, p. 348

- "Statute of Westminster 1931", legislation.gov.uk, archived from the original on 24 December 2012, retrieved 20 July 2017

- Rose, pp. 373–379

- Bogdanor, V. (1991), "1931 Revisited: The constitutional aspects", Twentieth Century British History, 2 (1): 1–25, doi:10.1093/tcbh/2.1.1

- Williamson, Philip (1991), "1931 Revisited: The political realities", Twentieth Century British History, 2 (3): 328–338, doi:10.1093/tcbh/2.3.328

- Nicolson, pp. 521–522; Owens, pp. 92–93; Rose, p. 388

- Nicolson, pp. 521–522; Rose, p. 388

- Sinclair p. 154

- Sinclair, p. 1

- Pimlott, Ben (1996), The Queen, John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-19431-6

- Ziegler, Philip (1990), King Edward VIII: The Official Biography, London: Collins, p. 199, ISBN 978-0-00-215741-4

- Rose, p. 392

- Windsor, pp. 118–119

- Rose, pp. 301, 344

- "The Illness of H. M. the King-Emperor". The Indian Medical Gazette. 64 (3): 151–152. March 1929. PMC 5164308. PMID 29009522.

- Ziegler, pp. 192–196

- Arthur Bigge, 1st Baron Stamfordham, to Alexander Cambridge, 1st Earl of Athlone, 9 July 1929, quoted in Nicolson p. 433 and Rose, p. 359

- Pope-Hennessy, p. 546; Rose, pp. 359–360

- Roberts, Andrew (2000), Fraser, Antonia (ed.), The House of Windsor, London, UK: Cassell and Co., p. 36, ISBN 978-0-304-35406-1

- Ashley, Mike (1998), The Mammoth Book of British Kings and Queens, London, UK: Robinson Publishing, p. 699

- Rose, pp. 360–361

- Bradford, Sarah (1989), King George VI, London, UK: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, p. 149, ISBN 978-0-297-79667-1

- Pope-Hennessy, p. 558

- The Times (London), 22 January 1936, p. 7, col. A

- The Times (London), 21 January 1936, p. 12, col. A

- Rose, p. 402

- Watson, Francis (1986), "The death of George V", History Today, vol. 36, pp. 21–30, PMID 11645856

- Lelyveld, Joseph (28 November 1986), "1936 Secret is out: Doctor sped George V's death", The New York Times, pp. A1, A3, PMID 11646481, archived from the original on 8 October 2016, retrieved 18 September 2016

- Ramsay, J.H.R. (28 May 1994), "A king, a doctor, and a convenient death", British Medical Journal, 308 (6941): 1445, doi:10.1136/bmj.308.6941.1445, PMC 2540387, PMID 11644545 (Subscription required)

- Matson, John (1 January 2012), Sandringham Days: The Domestic Life of the Royal Family in Norfolk,1862–1952, The History Press, ISBN 9780752483115

- "Doctor murdered Britain's George V", Observer-Reporter, Washington (PA), 28 November 1986, archived from the original on 3 November 2020, retrieved 18 September 2016

- The death of His Majesty King George V 1936 (short film / newsreel), British Pathé, 23 January 1936, archived from the original on 4 May 2016, retrieved 18 September 2016

- Steinberg, Michael (2000), The Concerto, Oxford University Press, pp. 212–213, ISBN 978-0-19-513931-0, archived from the original on 8 October 2021, retrieved 11 November 2020

- Windsor, p. 267

- The Times (London), Tuesday, 28 January 1936, p. 10, col. F

- Rose, pp. 404–405

- "No. 34350", The London Gazette, 15 December 1936, p. 8117

- Rose, p. 318

- e.g. Harold Nicolson's diary quoted by Sinclair, p. 107; Best, Nicholas (1995), The Kings and Queens of England, London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p. 83, ISBN 0-297-83487-8,

rather a dull man ... liked nothing better than to sit in his study and look at his stamps

; Lacey, Robert (2002), Royal, London, UK: Little, Brown, p. 54, ISBN 0-316-85940-0,the diary of King George V is the journal of a very ordinary man, containing a great deal more about his hobby of stamp collecting than it does about his personal feelings, with a heavy emphasis on the weather.

- Pierce, Andrew (4 August 2009), "Buckingham Palace is unlikely shrine to the history of jazz", The Telegraph, London, archived from the original on 27 December 2019, retrieved 11 February 2012

- Clay, p. 245; Gore, p. 293; Nicolson, pp. 33, 141, 510, 517

- Harrison, Brian (1996), The Transformation of British Politics, 1860–1995, pp. 320, 337

- Gore, pp. x, 116

- Cannadine, David (1998), History in our Time, p. 3

- Harrison, p. 332; "The King of England: George V", Fortune, p. 33, 1936,

if not himself a characteristic example of the great British middle class, is so like the characteristic examples of that class that there is no perceptible distinction to be made between the two.

- Rose, p. 328

- Harrison, pp. 51, 327

- Velde, François (19 April 2008), "Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family" Archived 17 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Heraldica, retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Louda, Jiří; Maclagan, Michael (1999), Lines of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe, London: Little, Brown, pp. 34, 51, ISBN 978-1-85605-469-0

Works cited

- Clay, Catrine (2006), King, Kaiser, Tsar: Three Royal Cousins Who Led the World to War, London: John Murray, ISBN 978-0-7195-6537-3

- Gore, John (1941), King George V: a personal memoir

- Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004; online edition May 2009), "George V (1865–1936)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33369, retrieved 1 May 2010 (Subscription required)

- Mowat, Charles Loch (1955), Britain Between The Wars 1918–1940, London: Methuen

- Nicolson, Sir Harold (1952), King George the Fifth: His Life and Reign, London: Constable and Co

- Owens, Edward (2019), "2: 'A man we understand': King George V's radio broadcasts", The Family Firm: monarchy, mass media and the British public, 1932–53, pp. 91–132, ISBN 9781909646940, JSTOR j.ctvkjb3sr.8

- Pope-Hennessy, James (1959), Queen Mary, London: George Allen and Unwin, Ltd

- Rose, Kenneth (1983), King George V, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-78245-2

- Sinclair, David (1988), Two Georges: The Making of the Modern Monarchy, London: Hodder and Stoughton, ISBN 978-0-340-33240-5

- Vickers, Hugo (2018), The Quest for Queen Mary, London: Zuleika

- Windsor, HRH The Duke of (1951), A King's Story, London: Cassell and Co

Further reading

- Cannadine, David (2014), George V: The Unexpected King

- Chisholm, Hugh (1922), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 31 (12th ed.)

- Mort, Frank (2019), "Safe for Democracy: Constitutional Politics, Popular Spectacle, and the British Monarchy 1910–1914", Journal of British Studies, 58 (1): 109–141, doi:10.1017/jbr.2018.176, S2CID 151146689

- Ridley, Jane (2022), George V: Never a Dull Moment, excerpt

- Somervell, D. C. (1936), The Reign of King George V, wide-ranging political, social and economic coverage, 1910–35

- Spender, John A. (1935), "British Foreign Policy in the Reign of HM King George V", International Affairs, 14 (4): 455–479, JSTOR 2603463

External links

- George V at the official website of the British monarchy

- George V at the official website of the Royal Collection Trust

- George V at BBC History

- Portraits of King George V at the National Portrait Gallery, London

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)