Cao Cao

Cao Cao (ⓘ; [tsʰǎʊ tsʰáʊ]; Chinese: 曹操; c. 155 – 15 March 220),[1] courtesy name Mengde, was a Chinese statesman, warlord and poet who rose to power towards the end of the Eastern Han dynasty (c. 184–220) and became the effective head of the Han central government during that period. He laid the foundation for what was to become the state of Cao Wei (220–265), established by his son and successor Cao Pi, who ended the Eastern Han dynasty and inaugurated the Three Kingdoms period (220–280). Beginning in his own lifetime, a corpus of legends developed around Cao Cao which built upon his talent, his cruelty, and his perceived eccentricities.

| Cao Cao 曹操 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Ming dynasty illustration of Cao Cao in the Sancai Tuhui. | |||||||||||||

| King of Wei (魏王) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 216 – 15 March 220 | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Cao Pi | ||||||||||||

| Duke of Wei (魏公) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 213–216 | ||||||||||||

| Imperial Chancellor (丞相) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 208 – 15 March 220 | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Cao Pi | ||||||||||||

| Minister of Works (司空) | |||||||||||||

| Tenure | 196–208 | ||||||||||||

| Born | c. 155 Qiao County, Pei State, Han Empire | ||||||||||||

| Died | 15 March 220 (aged 64–65) Luoyang, Han Empire | ||||||||||||

| Burial | 11 April 220 | ||||||||||||

| Spouse |

| ||||||||||||

| Issue (among others) | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Father | Cao Song | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Lady Ding | ||||||||||||

| Cao Cao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Cao Cao" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 曹操 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

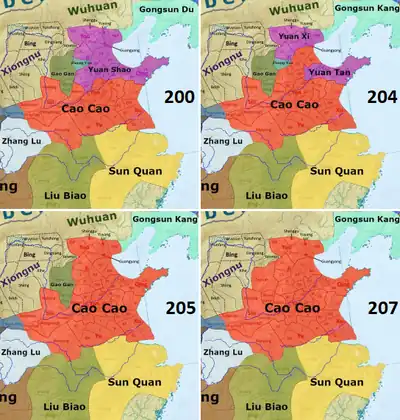

Cao Cao began his career as an official under the Han government and held various appointments, including that of a district security chief in the capital and the chancellor of a principality. He rose to prominence in the 190s during which he recruited his own followers, formed his own army, and set up a base in Yan Province (covering parts of present-day Henan and Shandong). In 196, he received Emperor Xian, the figurehead Han sovereign who was previously held hostage by other warlords such as Dong Zhuo, Li Jue, and Guo Si. After he established the new imperial capital in Xuchang, Emperor Xian and the central government came under his direct control, but he still paid nominal allegiance to the emperor. Throughout the 190s, Cao Cao actively waged wars in central China against rival warlords such as Lü Bu, Yuan Shu, and Zhang Xiu, eliminating all of them. Following his triumph over the warlord Yuan Shao at the Battle of Guandu in 200, Cao Cao launched a series of campaigns against Yuan Shao's sons and allies over the following seven years, defeated them, and unified much of northern China under his control. In 208, shortly after Emperor Xian appointed him as Imperial Chancellor, he embarked on an expedition to gain a foothold in southern China, but was defeated by the allied forces of the warlords Sun Quan, Liu Bei, and Liu Qi at the decisive Battle of Red Cliffs.

His subsequent attempts over the following years to annex the lands south of the Yangtze River never proved successful. In 211, he defeated a coalition of western warlords led by Ma Chao and Han Sui at the Battle of Tong Pass. Five years later, he seized Hanzhong from the warlord Zhang Lu but lost it to Liu Bei by 219. In the meantime, he also received many honours from Emperor Xian. In 213, he was created Duke of Wei and granted a fief covering parts of present-day Hebei and Henan. In 216, he was elevated to the status of a vassal king under the title "King of Wei" and awarded numerous ceremonial privileges, of which some used to be reserved exclusively for emperors. Cao Cao died in Luoyang in March 220 and was succeeded by his son Cao Pi, who accepted the abdication of Emperor Xian in November 220 and established the state of Cao Wei to replace the Eastern Han dynasty— an event commonly seen as a usurpation. This marked the transition from the Eastern Han dynasty to the Six Dynasties period. After taking the throne, Cao Pi granted his father the posthumous title "Emperor Wu" ("Martial Emperor") and the temple name "Taizu" ("Grand Ancestor").

Apart from being lauded as a brilliant political and military leader, Cao Cao is celebrated for his poems, which were characteristic of the Jian'an style of Chinese poetry. Opinions of him have remained divided from as early as the Jin dynasty (265–420) – the period immediately after the Three Kingdoms era – to the present. There were some who praised him for his achievements in poetry and his career, but there were also others who condemned him for his cruelty, cunning, and allegedly traitorous ways. In traditional Chinese culture, Cao Cao is stereotypically portrayed as a sly, power-hungry, and treacherous tyrant who serves as a nemesis to Liu Bei, often depicted in contraposition as a hero trying to revive the declining Han dynasty. During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), when Luo Guanzhong wrote the epic novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, which dramatises the historical events before and during the Three Kingdoms period, he not only cast Cao Cao as a primary antagonist in the story but also introduced, fictionalised, and exaggerated certain events to enhance Cao Cao's "villainous" image.

Historical sources on Cao Cao's life

The authoritative historical source on Cao Cao's life is his official biography in the Records of the Three Kingdoms (Sanguozhi), which was written by Chen Shou in the third century. His sources for his work on the Wei portion of his book (魏志; Wei Zhi) included the Dongguan Ji (東觀記; now lost), the Book of Wei, and possibly other records. Chen Shou worked in the history bureau and had access to a variety of sources, but followed the traditional method of incorporating information into a single synthesis without citing his sources, so it is not clear how broad a pool of documentation he drew upon.[A 1]

In the fifth century, Pei Songzhi annotated the Sanguozhi by incorporating information from other sources to Chen Shou's original work and adding his personal commentary, as well as commentary from other historians.

One of the major sources for information on Cao Cao's life employed by Pei Songzhi was the official history of the Wei dynasty, the Book of Wei (魏書), largely composed during the Wei dynasty itself by Wang Chen, Xun Yi, and Ruan Ji. It was completed by Wang Chen and presented to the court during the opening years of the succeeding Western Jin dynasty. This work is understandably typically very favourable to Cao Cao as the founding figure of the dynasty under which the initial compilation was performed.

As a counterpoint, another significant source for Cao Cao's life as cited by Pei Songzhi was the Cao Man zhuan (曹瞞傳), an anonymous collection of anecdotes said to have been compiled by a person from Eastern Wu, a rival kingdom to Cao Cao's own. This work is overall very hostile to Cao Cao, depicting him as cruel and untrustworthy, although not every anecdote is negative. Cao Man zhuan has been characterised as "hostile propaganda",[2] and certain contents as "slanderous".[3] Such a work cannot be considered a reliable source, but informs an exaggerated perspective contraposed to the glowing portrait painted by his own dynasty's official history.

For much of his career, Cao Cao hosted and controlled the final Han emperor, whose doings and correspondence it was standard to record. Especially useful for noting things like official appointments, three titles of this type were used by Pei Songzhi to add detail to Chen Shou's account: Xiandi Ji (獻帝記; Records of Emperor Xian) compiled by Liu Ai (劉艾), Xiandi Qiju zhu (獻帝起居注; Notes on Emperor Xian's Daily Life), and Shanyang Gong zaiji (山陽公載記; Records of the Duke of Shanyang [Emperor Xian's post-usurpation title]) by Yue Zi (樂資).

Other early sources for Pei Songzhi included Yu Huan's privately composed histories Dianlüe (典略; Authoritative Account) and Weilüe (魏略; Brief History of Wei), written prior to Chen Shou's own work; and Sima Biao's Jiuzhou Chunqiu (九州春秋; Annals of the Nine Provinces), also from the 3rd century.

Later sources included works by the moralistic historian Sun Sheng, most saliently his Wei Shi Chunqiu (魏氏春秋; Chronicles of the Ruling Family of Wei), but also his more critical Yitong Ping (異同評; Commentary on Similarities and Differences) and Yitong Zayu (異同雜語; Miscellaneous Words on Similarities and Differences), which may have been parts of the same work. Although Pei Songzhi sometimes pointed out flaws in Sun Sheng's methods, he often cite him as an authority. Other Jin dynasty historians he gave less credence to, while still including parallel passages from their work, such as Jiangbiao zhuan (江表傳), by Yu Pu (虞溥), and Wei Jin Shiyu (魏晉世語; Tales of the Worlds of Wei and Jin) by Guo Song (郭頒), a work which Pei Songzhi denigrated in very strident terms.[B 2]

The official standard history of the Eastern Han dynasty, the Book of the Later Han by Fan Ye, was not available to Pei Songzhi. He and Fan Ye were contemporaries, but Fan Ye did not begin work on his history until a few years after Pei Songzhi completed his. Book of the Later Han does not contain a full biography of Cao Cao, but records of him and his actions can be found scattered in disparate locations in the book.

Some of Cao Cao's own writing – both literary and in the form of government edicts – has been preserved in later collectanea. His commentary on The Art of War is extant, but offers little insight into his life.[4]

Family background and early life (155–184)

Cao Cao's ancestral home was in Qiao County (譙縣), Pei State (沛國), which is present-day Bozhou, Anhui.[5] He was purportedly a descendant of Cao Shen, a statesman of the early Western Han dynasty (206 BCE – 9 CE). His father, Cao Song, served as the Grand Commandant during the reign of Emperor Ling (r. 168–189), buying his way into high government office for an exorbitant sum, and serving less than half a year.[6] Cao Song was a foster son of Cao Teng, a eunuch who served as a Central Regular Attendant and the Empress's Chamberlain under Emperor Huan (r. 146–168), and held the peerage of Marquis of Fei Village (費亭侯).[A 2]

In his youth, Cao Cao was known to be perceptive and manipulative. He liked to hunt, idle, roam about freely, and play vigilante so he was not as highly regarded[A 3] compared to his more studious peers. From the time Cao Cao was fifteen until he turned thirty, widespread epidemic diseases ravaged China on average one out of every three years.[7]

Despite Cao Cao's loafing ways and unimpressive behaviour, there were two persons – Qiao Xuan[lower-alpha 1] and He Yong – who recognised his potential and extraordinary talents.[A 4] Upon visiting the famous commentator and character evaluator Xu Shao, Cao Cao was assessed as being "a treacherous villain in times of peace, and a hero in times of chaos".[8] Another source recorded that Xu Shao told Cao Cao, "You will be a capable minister in times of peace, and a jianxiong[lower-alpha 2] in times of chaos."[B 3][lower-alpha 3]

Early career (184–189)

| A summary of the major events in Cao Cao's life | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year(s) | Age | Event(s) |

| 155 | 0 | Born in Qiao County, Pei State (present-day Bozhou, Anhui) |

| Early career | ||

| 174 | 19 | Nominated as a xiaolian (civil service candidate) |

| 174–183 | 19–28 | Consecutively held the following appointments:

|

| 184 | 29 | Appointed as a Cavalry Commandant and led imperial forces to attack Yellow Turban rebels in Yingchuan (around present-day Xuchang, Henan) |

| 184–189 | 29–34 | Consecutively held the following appointments:

|

| 190 | 35 | Participated in the campaign against Dong Zhuo |

| Middle career | ||

| 191–192 | 36–37 | Took control of Yan Province (covering parts of present-day Shandong and Henan) and established his own army |

| 196 | 41 | Received Emperor Xian and established the new capital in Xuchang, Henan; Appointed Minister of Works and acting General of Chariots and Cavalry |

| 193–199 | 38–44 | Waged wars against rival warlords in central China and eliminated them in the following order: |

| 200 | 45 | Defeated Yuan Shao at the Battle of Guandu |

| 202–207 | 47–52 | Defeated Yuan Shao's heirs and the Wuhuan tribes and unified northern China under his control |

| 208 | 53 | Appointed by Emperor Xian as the Imperial Chancellor |

| 208–209 | 53–54 | Lost to Sun Quan and Liu Bei at the Battle of Red Cliffs |

| Later career | ||

| 211 | 56 | Defeated Ma Chao, Han Sui and other western warlords at the Battle of Tong Pass |

| 213 | 58 | Fought with Sun Quan at the Battle of Ruxu (213); Enfeoffed as the Duke of Wei and received a dukedom covering parts of present-day Hebei and Henan |

| 215–216 | 60–61 | Defeated Zhang Lu at the Battle of Yangping |

| 216 | 61 | Promoted from Duke of Wei to (vassal) King of Wei |

| 217 | 62 | Fought with Sun Quan at the Battle of Ruxu (217) |

| 218–219 | 63–64 | Lost to Liu Bei in the Hanzhong Campaign |

| 220 | 65 | Died in Luoyang |

| Posthumous honours | ||

| 220 | dead | Posthumously honoured as "King Wu" by Emperor Xian; Posthumously honoured as "Emperor Wu" with the temple name "Taizu" by Cao Pi after the establishment of the Cao Wei state |

As the Commandant of the North District in Luoyang

Cao Cao started his career as a civil service cadet after he was nominated as a xiaolian around the age of 19. He was later appointed as the Commandant of the North District (北部尉) of the imperial capital Luoyang and put in charge of maintaining security in that area. Later that year, he was transferred to the position of Prefect of Dunqiu County (頓丘縣; southwest of present-day Qingfeng County, Henan). This represented a horizontal career move to a position of greater authority in a smaller jurisdiction with less political importance.[A 5]

As a Consultant

Cao Cao's cousin married Song Qi (宋奇), a relative of Empress Song. In 178, when Emperor Ling deposed Empress Song in the aftermath of a political scandal, the empress's family and relatives got into trouble as well. Because of his relationship with Song Qi, Cao Cao was implicated in the scandal and dismissed from office. However, he was pardoned later and recalled to Luoyang to serve as a Consultant (議郎)[A 6] under the Minister of the Household because of his expertise in history. When the general Dou Wu and senior minister Chen Fan plotted to get rid of the eunuch faction, their plan failed and they lost their lives. Cao Cao wrote a memorial to Emperor Ling to defend Dou Wu and Chen Fan, and point out that the imperial court was full of corrupt officials and that advice from loyal officials had been ignored. Emperor Ling did not listen to him.[B 4]

Emperor Ling later issued a decree, ordering the Three Ducal Ministers to report and dismiss commandery and county officials who performed badly in office. However, the Ministers protected the under-performing officials and accepted bribes, resulting in a situation where evildoers were not punished while the poor and weak were oppressed. Cao Cao felt frustrated when he saw this. When natural disasters occurred, Cao Cao was summoned to the imperial court to discuss the problems in the administration. During this time, he wrote another memorial to Emperor Ling, accusing the Three Ducal Ministers of siding with the nobles and elites, and helping them to cover up their misdeeds. Emperor Ling was stunned after reading the memorial. He admonished the Ministers for their conduct, reinstated the officials who had been wrongly dismissed, and appointed them as Consultants. However, corruption worsened over time and became rampant throughout all levels of the government. Cao Cao stopped speaking up when he realised that his efforts to restore order were futile.[B 5]

As the Chancellor of Jinan

In 184, when the Yellow Turban Rebellion broke out, the Han central government commissioned Cao Cao as a Cavalry Commandant (騎都尉) and ordered him to lead imperial forces to attack the rebels in Yingchuan Commandery (潁川郡; around present-day Xuchang, Henan). He was later appointed as the Chancellor of Jinan State (濟南國; around present-day Jinan, Shandong), a principality in Qing Province which had over 10 counties under its jurisdiction. Many senior officials in Jinan State had connections with the nobles and engaged in corrupt practices, so Cao Cao proposed to the imperial court to dismiss about 80 percent of them. As Cao Cao had a reputation for being a strict law enforcer, when news of his arrival reached these corrupt officials, they were so fearful that they fled to nearby commanderies. Cao Cao governed Jinan State well and maintained peace in the area.[A 7][B 6]

In the early days of the Western Han, nearly four hundred years previously, Liu Zhang (劉章), the Prince of Chengyang State (城陽國; around present-day Ju County, Shandong), felt that he had made great contributions to the Han Empire so he built temples in his principality for the people to worship him. Many other commanderies in Qing Province also followed this practice. In Jinan State alone, there were over 600 such temples. Wealthy merchants could even borrow the servants and personal carriages of officials for their own leisure activities. This resulted in greater inequality between the rich and poor. The senior officials did not dare to interfere. When Cao Cao assumed office in Jinan State, he destroyed all the temples and banned such idolatrous practices. He upheld the laws sternly and eliminated unorthodox customs and cult-like activities.[B 7]

Brief resignation

After serving as the Chancellor of Jinan State for a brief period of time, Cao Cao was reassigned to be the Administrator of Dong Commandery (東郡; around present-day Puyang County, Henan), but he declined the appointment on the grounds of poor health, and resigned and went home.[A 8] The Book of Wei recorded that around the time, corruption had deteriorated to the point where influential officials dominated the imperial court and blatantly abused their powers. Cao Cao was unable to stop them and feared that he might bring trouble to his family because he had been interfering with their activities, so he requested to serve in the Imperial Guards. His request was rejected and he was appointed as a Consultant (議郎) instead. He then claimed that he was ill and resigned and went home. He built a house outside the city and lived there, spending his time reading in spring and summer, and going on hunting excursions in autumn and winter.[B 8]

Wang Fen (王芬), the Inspector of Ji Province, along with Xu You, Zhou Jing (周旌) and others, plotted to overthrow Emperor Ling and replace him with the Marquis of Hefei (合肥侯). They contacted Cao Cao and asked him to join them but he refused. Wang Fen's plan ultimately failed.[A 9]

Cao Cao was appointed as Colonel Who Arranges the Army (典軍校尉) and summoned back to Luoyang to serve in the Army of the Western Garden when Bian Zhang, Han Sui and others started a rebellion in Liang Province.[A 10]

Campaign against Dong Zhuo (189–191)

Background

Emperor Ling died in 189 and was succeeded by his son, Liu Bian, who is historically known as Emperor Shao. As Emperor Shao was still young, his mother Empress Dowager He and maternal uncle He Jin ruled as regents on his behalf. He Jin plotted with Yuan Shao and others to eliminate the eunuch faction, and shared their plan with his sister. When the empress dowager was reluctant to kill the eunuchs, He Jin thought of summoning generals stationed outside Luoyang to lead their troops into the imperial capital to put pressure on the empress dowager.[A 11] Cao Cao strongly objected to He Jin's idea as he believed that the best way to deal with the eunuchs was to eliminate their leaders. He also argued that summoning external forces into Luoyang would only increase the risk of their plan being leaked out.[B 9] He Jin – the highest ranking officer in the government – understandably ignored him.

As Cao Cao predicted, the eunuchs got wind of He Jin's plot and assassinated him before the generals and their troops arrived. Yuan Shao and He Jin's followers led their forces to storm the imperial palace and slaughter the eunuchs in revenge. Emperor Shao and his younger half-brother, Liu Xie, escaped during the chaos. They were eventually found and brought back to the palace by Dong Zhuo, who took advantage of the power vacuum to seize control of the central government. Later that year, Dong Zhuo deposed Emperor Shao and replaced him with Liu Xie, who is historically known as Emperor Xian. The deposed Emperor Shao became the Prince of Hongnong.[A 12]

Dong Zhuo wanted to appoint Cao Cao as a Colonel of Valiant Cavalry (驍騎校尉) and recruit him as an adviser. However, Cao Cao adopted a fake identity, escaped from Luoyang, and returned to his home in Chenliu Commandery (陳留郡; around present-day Kaifeng, Henan).[A 13] He had two encounters along the way. The first was with the family of Lü Boshe, an old acquaintance.[lower-alpha 4] The second incident occurred when he passed by Zhongmu County, where a village chief suspected that he was a fugitive and arrested him. However, another official recognised Cao Cao and believed he could act as a positive influence, so he released Cao Cao.[A 14]

The campaign

Dong Zhuo murdered the Prince of Hongnong and Empress Dowager He later. When Cao Cao returned to Chenliu Commandery, he spent his family fortune on raising an army to eliminate Dong Zhuo. In the winter of 189, Cao Cao assembled his forces in Jiwu County (己吾縣; southwest of present-day Ningling County, Henan) and declared war on Dong Zhuo.[A 15]

In early 190, several regional officials and warlords formed a coalition army numbering some tens of thousands, and launched a punitive campaign against Dong Zhuo. They declared that their mission was to free Emperor Xian and the central government from Dong Zhuo's control. Yuan Shao was elected as the coalition chief while Cao Cao served as acting General of Uplifting Martial Might (奮武將軍). The coalition scored some initial victories against Dong Zhuo's forces and reached Luoyang within months. Dong Zhuo, alarmed by his losses, ordered his troops to forcefully relocate Luoyang's residents to Chang'an and burn down the imperial capital, leaving behind nothing for the coalition.[A 16]

While Dong Zhuo was retreating to Chang'an, Cao Cao led his own army to pursue the enemy, but was defeated by Xu Rong, a general under Dong Zhuo, at the Battle of Xingyang. This was the first military action Cao Cao commanded, and he barely escaped alive, with help from his cousin Cao Hong. He returned to the coalition base in Suanzao County (酸棗縣; southwest of present-day Yanjin County, Henan) and was disgusted to see that the other coalition members were making merry instead of thinking how to make progress. He presented his plan on how to continue the war against Dong Zhuo and chided them for their lacklustre attitudes towards their initial goals. They ignored him.[A 17]

Aftermath

As Cao Cao had few troops left with him after the Battle of Xingyang, he travelled to Yang Province with Xiahou Dun to recruit soldiers. Chen Wen (陳溫), the Inspector of Yang Province, and Zhou Xin, the Administrator of Danyang Commandery (丹楊郡), gave him over 4,000 troops. On the way back, when they passed by Longkang County (龍亢縣; in present-day Huaiyuan County, Anhui), many soldiers started a mutiny and set fire to Cao Cao's tent at night, but he was able to escape.[B 10] When Cao Cao reached Zhi (銍; west of present-day Suzhou, Anhui) and Jianping (建平; southwest of present-day Xiayi County, Henan) counties later, he managed to regroup over 1,000 soldiers and lead them to a garrison in Henei Commandery (河內郡; around present-day Wuzhi County, Henan).[A 18]

Yuan Shao and Han Fu thought of installing Liu Yu, the Governor of You Province, on the throne to replace Emperor Xian. When they sought Cao Cao's opinion,[A 19] Cao Cao refused to support them and reaffirmed his allegiance to Emperor Xian.[B 11] Yuan Shao's plan turned out to be unsuccessful because Liu Yu himself did not want to be emperor.

Yuan Shao once invited Cao Cao to sit beside him and showed him a jade seal, indicating his imperial ambition, and a tacit request for Cao Cao's support. Finding this despicable, Cao Cao laughed at him.[A 20]

Military exploits in central China (191–199)

Pacifying Yan Province

Between 191 and 192, Yuan Shao appointed Cao Cao Administrator of Dong Commandery (東郡; around present-day Puyang, Henan) in Yan Province. This position allowed him to exact taxes and conscript soldiers. His first territorial command in that respect marks the beginning of his career as a warlord.[9] During this time, he defeated the Heishan bandits, who were causing trouble in the region, and some southern Xiongnu forces led by Yufuluo in Neihuang County.[A 21]

Around the time, huge numbers of remnants of the Yellow Turban rebels swarmed into Yan Province from Qingzhou. Liu Dai, the Governor of Yan Province, was killed in a battle against the rebels. Bao Xin, Chen Gong and others invited Cao Cao to replace Liu Dai as the Governor of Yan Province. Cao Cao defeated the rebels in battle and received the surrender of over 300,000 rebels and hundreds of thousands of civilians (the rebels' family members). From among them, he recruited the more battle-hardened ones to form a new military unit known as the Qingzhou Corps (青州兵).[A 22]

Involvement in the conflict between Yuan Shao and Yuan Shu

Yuan Shu had disagreements with Yuan Shao so he contacted Gongsun Zan, Yuan Shao's rival in northern China, for help in dealing with Yuan Shao. Gongsun Zan instructed Liu Bei, Shan Jing (單經) and Tao Qian to garrison at Gaotang, Pingyuan and Fagan (發干; east of present-day Guan County, Shandong) counties respectively to put pressure on Yuan Shao. Yuan Shao allied with Cao Cao and defeated all the opposing forces. In the spring of 193, Cao Cao defeated Yuan Shu at the Battle of Fengqiu and returned to Dingtao County by summer.[A 23]

Conflict with Tao Qian

Between 193 and 194, Cao Cao came into conflict with Tao Qian, the Governor of Xu Province, and attacked Xu Province three times. The first attack took place in the autumn of 193, when Cao Cao attacked Tao Qian after the latter supported Que Xuan (闕宣), who had committed treason by declaring himself emperor.[A 24] The second and third invasions were triggered by the murder of Cao Cao's father, Cao Song, in Xu Province, which occurred when Cao Song was en route to Qiao County (譙縣; present-day Bozhou, Anhui) after his retirement. Although Tao Qian's culpability in the murder was questionable, Cao Cao nonetheless held him responsible for his father's death. During the invasions, Cao Cao conquered several territories in Xu Province and massacred thousands of civilians.[A 25] Cao Cao's assault on Xu Province was so brutal that after one massacre the corpses of his victims stoppered up the nearby Si river (泗水).[A 26] His army tore down villages in its wake, ensuring refugees could not return, and ate all the chickens and dogs. Cao Cao only turned back when he received news that his base in Yan Province had fallen to Lü Bu.

War with Lü Bu

In 194, Cao Cao's subordinates Zhang Miao, Chen Gong and others rebelled against him in Yan Province and defected to a rival warlord, Lü Bu. Many commanderies and counties in Yan Province responded to Lü Bu's call and defected to his side except for a few. Cao Cao aborted his campaign in Xu Province and returned to attack Lü Bu. In one battle at Puyang County, he fell into an ambush and suffered some burns but managed to survive and escape. Cao Cao and Lü Bu were locked in a stalemate at Puyang County for over 100 days until Lü Bu left the county when his supplies ran out due to natural disasters such as locust plagues and droughts.[A 27] Grain supplies were so limited that Cao Cao strongly considered an offer to serve under Yuan Shao, but was persuaded against it and ceased recruitment instead. He sent his army to collect food, but his numerically inferior forces were able to turn back an attack by Lü Bu that summer using deceptive tactics.[A 28][B 12]

From 194 to late 195, Cao Cao attacked the territories in Yan Province and managed to retake them from Lü Bu. Lü Bu fled east to Xu Province and took refuge under Liu Bei, who had succeeded Tao Qian as the Governor of Xu Province earlier in 194. In the winter of 195, the central government officially designated Cao Cao as the Governor of Yan Province.[A 29]

In 196, Lü Bu turned against his host and seized control of Xu Province from Liu Bei, but still allowed Liu Bei to remain in Xiaopei (小沛; present-day Pei County, Jiangsu). Although he agreed to an alliance with Yuan Shu earlier, he broke his promise and severed ties with Yuan Shu when the latter declared himself emperor in early 197.[Z 1] Throughout 197, Lü Bu joined Cao Cao and others in attacking Yuan Shu, who had become a public enemy because of his treasonous actions.[A 30] However, in 198, Lü Bu sided with Yuan Shu again and attacked Liu Bei, who lost and fled to join Cao Cao. In the winter of 198, Cao Cao and Liu Bei combined forces to attack Lü Bu and defeated him at the Battle of Xiapi. Lü Bu was captured and executed after his defeat. Cao Cao also pacified the eastern parts of Xu and Qing provinces along the coast.[A 31]

Receiving Emperor Xian

Emperor Xian had been held hostage in Chang'an by Li Jue, Guo Si and other former followers of Dong Zhuo. Around 195, when internal conflict broke out between Li Jue and Guo Si, Emperor Xian escaped from Chang'an and after a harrowing journey returned to the ruins of Luoyang, which Dong Zhuo had ordered to be destroyed by fire in 190 when moving the capital to Chang'an. In Luoyang, Emperor Xian came under the protection of Dong Cheng, former bandit Yang Feng, and other petty strongmen who have been characterised as "ragtag gangsters".[10] The emperor sought refuge under Yuan Shao, but was rebuffed.[11] In February or March 196, acting on the advice of Xun Yu and Cheng Yu, Cao Cao sent Cao Hong west to fetch Emperor Xian but was blocked by Dong Cheng and Yuan Shu's subordinate Chang Nu (萇奴). Between March and April 196, Cao Cao attacked and defeated Yellow Turban rebel remnants in Runan (汝南) and Yingchuan (潁川) commanderies and was appointed General Who Establishes Virtue (建德將軍). In July or August 196, Cao Cao was promoted to General Who Garrisons the East (鎮東將軍) and enfeoffed as the Marquis of Fei Village (費亭侯) – the peerage previously held by his adoptive grandfather Cao Teng.[A 32]

Sometime between August and September 196, Cao Cao led his forces to the ruins of Luoyang and received Emperor Xian. The emperor granted Cao Cao a ceremonial axe and appointed him Manager of the Affairs of the Imperial Secretariat (錄尚書事) and Colonel-Director of Retainers (司隷校尉).[B 13] As Luoyang was in bad shape, Dong Zhao and others advised Cao Cao to move the imperial capital to Xu (許; present-day Xuchang, Henan). So, in October or early November 196, Cao Cao and his forces escorted Emperor Xian to Xuchang, which became the new imperial capital. Cao Cao had himself appointed General-in-Chief (大將軍) and promoted from a village marquis to a county marquis under the title "Marquis of Wuping" (武平侯), later characterised as ten thousand households.[B 14] Since Dong Zhuo moved the capital from Luoyang to Chang'an in 190, the imperial court had been in a state of disorder. However, after Cao Cao received Emperor Xian and established the new imperial capital in Xuchang, order was restored,[A 33] although Cao Cao did have the emperor's confidante Zhao Yan (趙彥) killed for secretively keeping the emperor updated on the great affairs of state.[12]

Cao Cao sent an imperial decree to Yuan Shao in Emperor Xian's name to appoint him as Grand Commandant (太尉). Yuan Shao was unhappy because Grand Commandant ranked below Cao Cao's position, General-in-Chief, so he rejected the appointment. When Cao Cao heard about it, he gave up his position as General-in-Chief and offered it to Yuan Shao. Emperor Xian reappointed Cao Cao as Minister of Works (司空) and acting General of Chariots and Cavalry (車騎將軍). Struck by the difficulties Yuan Shao and Yuan Shu had faced in supplying their armies, as well as his own struggles with food supply in recent years, Cao Cao followed Zao Zhi (棗祗) and Han Hao's suggestion to implement the tuntian system of agriculture[A 34] to produce a sustainable supply of grain for his growing army.[B 15] The tuntian agricultural colonies gave Cao Cao an advantage over his adversaries, allowing him to resettle internally displaced refugees, redevelop abandoned arable lands, shorten his supply lines, reduce the amount of defensive assets tasked to defend farms and granaries, and increase the area and productivity of lands held directly by the state.[13]

Battles with Zhang Xiu

In early 197, Cao Cao led his forces to Wancheng (宛城; present-day Wancheng District, Nanyang, Henan) to attack a rival warlord, Zhang Xiu. Zhang Xiu initially surrendered without a fight, but due to ill treatment changed his mind and attacked Cao Cao and caught him off guard. Cao Cao lost his eldest son Cao Ang, nephew Cao Anmin (曹安民) and close bodyguard Dian Wei in the battle. He returned to Xuchang after his defeat, but attacked Zhang Xiu again later that year and pacified Huyang (湖陽; southwest of present-day Tanghe County, Henan) and Wuyin (舞陰; southeast of present-day Sheqi County, Henan) counties. In early 198, he led another campaign against Zhang Xiu and besieged him in Rangcheng (穰城; present-day Dengzhou, Henan) but withdrew his forces about two months later. Before retreating back to Xuchang, he set up an ambush and defeated Zhang Xiu's pursuing forces. In late 199, acting on Jia Xu's advice, Zhang Xiu voluntarily surrendered to Cao Cao, who accepted his surrender.[A 35]

Campaign against Yuan Shu

In early 197, Yuan Shu declared himself emperor in Shouchun (壽春; present-day Shou County, Anhui) – an act regarded as treason against Emperor Xian. He soon came under attack by Cao Cao and various forces, including his former ally Lü Bu. In the autumn of 197, Cao Cao defeated Yuan Shu in battle, captured several of his officers, and had them executed. By 199, some months after Lü Bu's defeat at the Battle of Xiapi, Yuan Shu, who was already in dire straits, wanted to abandon his lands in the Huainan region and head north to join Yuan Shao. Cao Cao sent Liu Bei and Zhu Ling to lead forces to intercept and block Yuan Shu in Xu Province. Yuan Shu died of illness while under siege by Liu Bei and Zhu Ling.[A 36]

War with Yuan Shao (199–202)

Background

While Cao Cao was waging wars throughout central China in the 190s, Yuan Shao defeated his rival Gongsun Zan at the Battle of Yijing in 199, after which he controlled four provinces in northern China (Ji, Bing, Qing and You) and gained command of thousands of troops. A power struggle between Cao Cao and Yuan Shao became inevitable by early 199. In the autumn of 199, Cao Cao dispatched troops to Liyang County (黎陽縣; present-day Xun County, Henan) and sent Zang Ba and others to capture some territories in Qing Province while leaving Yu Jin to guard the southern bank of the Yellow River. In winter, he mobilised his forces and deployed them at Guandu (官渡; present-day Guandu Town, Zhongmu County, Henan).[A 37]

Campaign against Liu Bei in Xu Province

Around this time, Cheng Yu and Guo Jia had warned Cao Cao against allowing Liu Bei to leave Xuchang but it was too late because Cao Cao had already sent Liu Bei to intercept and block Yuan Shu. Earlier, when he was still in Xuchang, Liu Bei had secretly joined a plot initiated by Dong Cheng and others to get rid of Cao Cao. After leaving Xuchang, Liu Bei headed to Xu Province, killed the provincial inspector Che Zhou (車冑), and seized control of Xu Province. Cao Cao sent Liu Dai (劉岱)[lower-alpha 5] and Wang Zhong to attack Liu Bei but they were defeated.[A 38]

In February 200, Cao Cao got wind of Dong Cheng's plot and had all the conspirators arrested and executed. He then led a campaign to retake Xu Province from Liu Bei, defeated him, and captured his family. Liu Bei's general Guan Yu, who was guarding Xu Province's capital, Xiapi (下邳; present-day Pizhou, Jiangsu), surrendered and temporarily served Cao Cao. Liu Bei fled north to join Yuan Shao after his defeat. Some of Cao Cao's subordinates initially expressed worries that Yuan Shao might attack them while Cao Cao was away in Xu Province, but, as Cao Cao accurately predicted,[lower-alpha 6] Yuan Shao did not make any advances throughout this period of time,[A 39] possibly due to Cao Cao's general Yu Jin's raiding in the south of Yuan Shao's territory.[A 40]

Early stages

From early to mid 200, the forces of Cao Cao and Yuan Shao clashed in two separate engagements at Boma (白馬; present-day Hua County, Henan) and Yan Ford (延津; near present-day Yanjin County, Henan). At Boma, Yuan Shao sent Guo Tu, Chunyu Qiong and Yan Liang to besiege Cao Cao's general Liu Yan (劉延), but the siege was lifted after about two months when Cao Cao personally led an army to relief Liu Yan. Guan Yu slew Yan Liang in the midst of battle. While Cao Cao and his troops were evacuating Boma's residents, Yuan Shao's forces led by Wen Chou and Liu Bei caught up with them at Yan Ford, but were defeated and Wen Chou was killed in battle. Cao Cao returned to his main camp at Guandu while Yuan Shao moved to Yangwu County (陽武縣; southwest of present-day Yuanyang County, Henan). Around this time, Guan Yu left Cao Cao and returned to Liu Bei.[A 41]

Stalemate at Guandu and the raid on Wuchao

In late 200, Yuan Shao led his forces to attack Cao Cao at Guandu. Both sides were locked in a stalemate for months and Cao Cao's supplies were gradually running out and his men were growing weary. During this time, Yuan Shao sent Liu Bei to contact a rebel chief, Liu Pi (劉辟), in Runan Commandery (汝南郡; around present-day Xinyang, Henan) and join Liu Pi in making a sneak attack on Cao Cao's base in Xuchang while Cao Cao was away at Guandu. However, Liu Bei and Liu Pi were defeated and driven back by Cao Cao's general Cao Ren. During this time, Sun Ce, a warlord based in the Jiangdong region, also contemplated attacking Xuchang and taking Emperor Xian hostage. However, he was assassinated before he could execute his plan.[A 42]

In the winter of 200, following the advice of Xu You, a defector from Yuan Shao's side, Cao Cao left Cao Hong behind to defend his main camp at Guandu while he personally led 5,000 riders to raid Yuan Shao's supply depot at Wuchao (烏巢; southeast of present-day Yanjin County, Henan), which was guarded by Chunyu Qiong. Cao Cao succeeded in destroying Yuan Shao's supplies. When Yuan Shao heard that Wuchao was under attack, he sent Zhang He and Gao Lan to attack Cao Cao's main camp in the hope of diverting Cao Cao's attention away from Wuchao. However, Zhang He and Gao Lan, already frustrated with Yuan Shao, destroyed their own camps and led their troops to defect to Cao Cao's side. The morale of Yuan Shao's army fell drastically and they were utterly defeated by Cao Cao's forces, after which Yuan Shao hastily crossed the Yellow River and retreated back to northern China. Much of his supplies and many of his soldiers were captured by Cao Cao. Cao Cao also obtained several letters written by spies from his side to Yuan Shao, but he refused to conduct an investigation to find out who the spies were, and instead ordered all the letters to be burnt. Many commanderies in Ji Province surrendered to Cao Cao.[A 43]

Aftermath

In the summer of 201, Cao Cao led his forces across the Yellow River and attacked Yuan Shao again, inflicting another crushing defeat on him at the Battle of Cangting and pacifying the territories in the area. In autumn, Cao Cao returned to Xuchang and sent Cai Yang (蔡揚) to attack Liu Bei, who had left Yuan Shao and allied with another rebel chief, Gong Du (共都),[lower-alpha 7] in Runan Commandery. Liu Bei defeated and killed Cai Yang in battle.[A 44] Cao Cao personally led his forces to attack Liu Bei, who fled south upon learning Cao Cao himself was in command. He took shelter under governor Liu Biao in Jing Province.[A 45] The following spring, while in his hometown, Cao Cao issued a proclamation characterising his military actions as a righteous uprising.[A 46]

Unification of northern China (202–207)

Battle of Liyang

Yuan Shao died of illness in the early summer of 202 and was succeeded by his third son, Yuan Shang. In autumn, Cao Cao attacked Yuan Shang and his eldest brother Yuan Tan and defeated them, forcing them to retreat and hold up inside their fortresses. In the spring of 203, Cao Cao attacked the Yuan brothers again and defeated them. In summer, he advanced towards Ye (present-day Handan, Hebei) and returned to Xuchang later, leaving behind Jia Xin (賈信) to defend Liyang County (黎陽縣; present-day Xun County, Henan).[A 47] Afterwards, Cao Cao issued an order establishing schools in each of his counties with 500 or more households.[A 48]

Defeating Yuan Shao's heirs

Some months after Cao Cao left northern China and returned to the south, internal conflict broke out between Yuan Shang and Yuan Tan as the brothers started fighting over Ji Province. Yuan Tan, who lost to Yuan Shang, surrendered to Cao Cao and sought his help in dealing with his third brother. Cao Cao agreed to assist Yuan Tan, so, in the winter of 203, he returned to northern China. Between spring and autumn in 204, Cao Cao attacked Yuan Shang in his base at Ye and conquered the city. Yuan Shang fled further north to Zhongshan Commandery (中山郡; around present-day Dingzhou, Hebei). After capturing Ye, Cao Cao visited Yuan Shao's tomb, weeping for his childhood friend-turned-rival, and spared no effort assuaging Yuan Shao's widow. To the delight of the people in Hebei, Cao Cao issued an order exempting them from paying taxes for that year and clamped down on the power of influential landlords in the area. When Emperor Xian offered to appoint Cao Cao as the Governor of Ji Province, Cao Cao declined, preferring to stick to his appointment as the Governor of Yan Province.[A 49]

While Cao Cao was attacking Yuan Shang in Ye, Yuan Tan, who had previously allied with Cao Cao against his third brother, took over some of Yuan Shang's territories and troops for himself. Cao Cao wrote to Yuan Tan to reprimand him for not adhering to their earlier agreement. Yuan Tan became afraid so he retreated to Nanpi County. In the spring of 205, Cao Cao attacked Yuan Tan, defeated him, and executed him along with his family. Ji Province was completely pacified. Around the same time, Yuan Shang had fled to join his second brother Yuan Xi but Yuan Xi was betrayed by his subordinates Jiao Chu (焦觸) and Zhang Nan (張南), who surrendered to Cao Cao. The Yuan brothers had no choice but to head further north to take shelter under the Wuhuan tribes.[A 50]

In the spring of 206, Cao Cao attacked Yuan Shao's maternal nephew Gao Gan, who had surrendered to him initially but rebelled later, and defeated Gao Gan at Hu Pass (壺關; in present-day Huguan County, Shanxi). In autumn, Cao Cao started a campaign against the pirates led by Guan Cheng (管承). He sent Yue Jin and Li Dian to attack Guan Cheng and pacified the eastern coast.[A 51]

Campaign against the Wuhuan

In the summer of 206, Cao Cao received the surrender of thousands of Heishan bandits led by Zhang Yan. Around the time, Zhao Du (趙犢) and Huo Nu (霍奴) killed the Inspector of You Province and the Administrator of Zhuo Commandery (涿郡; around present-day Zhuozhou, Hebei), while the Wuhuan tribes from three commanderies attacked Xianyu Fu (鮮于輔) at Guangping County (獷平縣; west of present-day Miyun District, Beijing). In early autumn, Cao Cao personally led a campaign against them and defeated Zhao Du and Huo Nu, after which his army crossed the Lu River (潞河; in present-day Tongzhou District, Beijing) to help Xianyu Fu by attacking the Wuhuan. They succeeded in driving the Wuhuan away. Cao Cao returned to Ye by winter.[A 52]

Throughout the period of civil wars during the late Eastern Han dynasty, the Wuhuan tribes in northern China had been taking advantage of the situation to invade You Province, capture and enslave thousands of people living in the area. When Yuan Shao was in power in northern China, he maintained friendly ties with the Wuhuan, so Yuan Shang and Yuan Xi found refuge under the Wuhuan chieftains. In 207, Cao Cao led a campaign against the Wuhuan and the Yuan brothers and scored a decisive victory over them at the Battle of White Wolf Mountain later that year. The campaign was difficult and dangerous, and Cao Cao rewarded his counselors who had advised him against undertaking it.[14] Yuan Shang and Yuan Xi fled further northeast to Liaodong to take shelter under the warlord Gongsun Kang. When Cao Cao's generals were preparing for an invasion of Liaodong, Cao Cao stopped them and predicted that Gongsun Kang would kill the Yuan brothers. Cao Cao was right, as Gongsun Kang arrested and executed the Yuan brothers because he sensed that they posed a threat to him. He then sent their heads to Cao Cao as a gesture of goodwill. Northern China was basically pacified and unified under Cao Cao's control by then.[A 53]

In the spring of 207, Cao Cao announced he would be distributing his wealth amongst those who had aided him, and enfeoffed over twenty of his followers as marquises, with lesser emoluments for the remainder.[A 54]

Red Cliffs campaign (207–211)

Background

Cao Cao returned to Ye (present-day Handan, Hebei) in the spring of 208 after pacifying northern China. He ordered the construction of Xuanwu Pool (玄武池) to train his troops in naval warfare. He also implemented changes to the political system by abolishing the Three Ducal Ministers and replacing them with the offices of the Imperial Chancellor (丞相) and Imperial Counsellor (御史大夫).[lower-alpha 8] He was officially appointed as Imperial Chancellor in July 208.[A 55] Around this time he had the famous scholar Kong Rong – later listed by Cao Cao's own son Cao Pi as one of the foremost literary talents of the age[15] – put to death for insousiance, along with his family.[16]

In August 208, Cao Cao launched a southern campaign to attack Liu Biao, the Governor of Jing Province. Liu Biao died of illness in the following month and was succeeded by his younger son, Liu Cong. Liu Cong was stationed at Xiangyang while Liu Bei moved from Xinye County to Fancheng (樊城; present-day Fancheng District, Xiangyang, Hubei). Liu Cong surrendered in late September or October 208 when Cao Cao and his forces reached Xinye County. Liu Bei and his followers fled towards Xiakou (夏口; in present-day Wuhan, Hubei) to join Liu Biao's elder son, Liu Qi. Cao Cao sent 5,000 riders to pursue Liu Bei and after covering 150 km (93 mi) in twenty-four hours[17] they caught up with him and defeated him at the Battle of Changban. Liu Bei managed to escape and retreat safely to Xiakou with a few followers, but lost most of his supplies and equipment to the enemy.[A 56] Liu Bei later formed an alliance with the warlord Sun Quan, who controlled the territories in the Wuyue region in southern China.

Meanwhile, Cao Cao advanced towards Jiangling County and reformed Jing Province's administration. He also rewarded those who helped him gain Jing Province, including those from Liu Cong's side who persuaded Liu Cong to surrender to him. Cao Cao appointed Wen Ping, a former general under Liu Biao, as the Administrator of Jiangxia Commandery (江夏郡; around present-day Xinzhou District, Wuhan, Hubei) and put him in command of some of his troops. He also recruited members of the scholar-gentry in Jing Province, such as Han Song (韓嵩) and Deng Yi, to serve under him.[A 57]

Battle of Red Cliffs

Liu Zhang, the Governor of Yi Province (covering present-day Sichuan and Chongqing), had received orders to help Cao Cao recruit soldiers from his province, so he sent the new conscripts to Jiangling County. In late December 208 or January 209, Sun Quan helped Liu Bei by attacking Cao Cao's garrison at Hefei. Around the same time, Cao Cao led his forces from Jiangling County to attack Liu Bei. When they reached Baqiu (巴丘; present-day Yueyang, Hunan), Cao Cao ordered Zhang Xi (張憙) to lead a separate army to reinforce Hefei, and Sun Quan withdrew his forces from Hefei upon receiving news of Zhang Xi's arrival.[lower-alpha 9] Cao Cao's forces advanced to Red Cliffs (赤壁) and engaged the allied forces of Liu Bei and Sun Quan, but lost the battle. Around that time, an epidemic disease had broken out in Cao Cao's army and many had died, so Cao Cao ordered a retreat. Liu Bei then went on to conquer the four commanderies in southern Jing Province.[A 58]

After his defeat at Red Cliffs, Cao Cao led his remaining forces through Huarong Trail (華容道; near present-day Jianli County, Hubei) as they were retreating. The area was very muddy and inaccessible and there were strong winds. Cao Cao ordered his weaker soldiers to carry straw and hay to lay out the path ahead so that his horsemen could proceed. The weaker soldiers ended up being stuck in the mud and many were trampled to death by the riders. Cao Cao expressed joy after he and his surviving men managed to get out of Huarong Trail safely, albeit suffering much losses. His generals were puzzled so they asked him why. Cao Cao remarked: "Liu Bei, my friend, doesn't think fast enough. If he had set fire earlier, we wouldn't have been able to get out alive." Liu Bei did think of setting fire but it was too late as Cao Cao had already escaped.[B 17]

After the Red Cliffs campaign

In the spring of 209, Cao Cao reached Qiao County (譙縣; present-day Bozhou, Anhui), where he ordered small boats to be built and staged a naval drill. In autumn, he sailed along the Huai River to the garrison at Hefei, where he issued an order for local officials to provide relief to the families of soldiers who had died in battle. He then established an administration in Yang Province and started a tuntian system in Quebei (芍陂; south of present-day Shou County, Anhui). He returned to Qiao County in winter.[A 59]

In the winter of 210, Cao Cao had a Bronze Sparrow Platform (or Bronze Sparrow Terrace)[lower-alpha 10] constructed in Ye.[A 60] In January 211, Cao Cao wrote a long memorial – to the throne as well as to a more general audience including his detractors – declining to accept three counties awarded to him by Emperor Xian to be part of his marquisate, in which he also wrote at length about his life and ambitions.[lower-alpha 11]

In the spring of 211, Emperor Xian appointed Cao Cao's son, Cao Pi, as General of the Household for All Purposes (五官中郎將). Cao Pi had his own office and served as an assistant to his father, the Imperial Chancellor.[A 61] At the same time, in accordance with Cao Cao's wishes in the essay he wrote earlier, Emperor Xian reduced the number of taxable households in Cao Cao's marquisate by 5,000, and granted the three counties to three of Cao Cao's sons – Cao Zhi, Cao Ju and Cao Lin[lower-alpha 12] – who were enfeoffed as marquises.[B 18]

Sometime in early 211, Shang Yao (商曜) from Taiyuan Commandery started a rebellion in Daling County (大陵縣; north of present-day Wenshui County, Shanxi). Cao Cao sent Xiahou Yuan and Xu Huang to lead an army to suppress the revolt and they achieved success.[A 62]

Battle of Tong Pass (211–213)

In early 211, Cao Cao ordered Zhong Yao and Xiahou Yuan to lead an army to attack Zhang Lu in Hanzhong Commandery. They were due to pass through the Guanzhong region along the way. The warlords in Guanzhong thought that Cao Cao was planning to attack them, so they, under the leadership of Ma Chao and Han Sui, formed a coalition known as the Guanxi Coalition (關西軍; "coalition from the west of (Tong) Pass") and rebelled against the Han imperial court.[A 63]

A few months later, Cao Cao personally led a campaign against the rebels and engaged them in battle in the areas around Tong Pass (in present-day Tongguan County, Shaanxi) and the banks of the Wei River. The first engagement took place when Cao Cao's forces were crossing the Wei River to the north bank, during which they suddenly came under attack by Ma Chao. Cao Cao and his forces headed back to the south bank later, where they constructed sand walls to keep the enemy at bay.[A 64]

After some time, the rebels offered to cede territories and send a hostage to Cao Cao's side in exchange for peace. Acting on Jia Xu's suggestion, Cao Cao pretended to accept the offer to put the enemy at ease and make them lower their guard. Cao Cao later had talks with Han Sui (an old acquaintance of his) on at least two different occasions. The first time was a private conversation between them about old times, while the second time probably took place in the presence of Ma Chao and the other coalition members. Ma Chao and the others started to doubt Han Sui's allegiance,[B 19] especially after Han Sui received a letter from Cao Cao which contained several blotted-out words, making it seem as though the recipient had deliberately edited the letter's contents to cover up something. Cao Cao took advantage of the mutual suspicion between the rebels to launch an attack on them and defeated them. Some of the warlords were killed in battle while Han Sui and Ma Chao retreated back to Guanzhong.[A 65]

Aftermath

Cao Cao returned to Ye (present-day Handan, Hebei) in late 211 after receiving the surrender of one of the remaining warlords, Yang Qiu. He left Xiahou Yuan behind to defend Chang'an, a major city in the Guanzhong region. Ma Chao, who had the support of the Qiang, Di and other tribal peoples in western China, continued to ravage Guanzhong and attack Cao Cao's territories. In 213, he killed Wei Kang, the Inspector of Liang Province, seized control of the province, and forced Wei Kang's subordinates to submit to him. In late 213, Zhao Qu (趙衢), Yin Feng (尹奉) and several other officials in Liang Province rebelled against Ma Chao and drove him out of Guanzhong. With aid from Zhang Lu, Ma Chao returned and struck back at his enemies, but was defeated when Xiahou Yuan led reinforcements from Chang'an to assist Zhao Qu and his allies. Xiahou Yuan later attacked the remnants of the Guanxi Coalition (including Han Sui) and the various tribes in western China and forced them to surrender. He also eliminated Song Jian (宋建), who had rebelled against the Han government and set up a small kingdom in Fuhan County (枹罕縣; southwest of present-day Linxia County, Gansu).[A 66]

Wars with Sun Quan (213–217)

In early 213, Cao Cao led an army to attack Sun Quan at Ruxu (濡須; north of present-day Wuwei County, Anhui, along the Yangtze River). During the battle, Cao Cao's forces destroyed Sun Quan's camp on the west bank of the Yangtze and captured Gongsun Yang (公孫陽), an area commander under Sun Quan. However, overall, both sides did not make any significant gains in the battle.[A 67]

In mid-214, Cao Cao launched another campaign against Sun Quan against the advice of Fu Gan (傅幹), one of his advisers. Just like in the previous campaign, he did not make any significant gains so he retreated. In the following year, Sun Quan led his forces to attack Hefei, a heavily fortified city guarded by Cao Cao's generals Zhang Liao, Li Dian and Yue Jin, leading to the Battle of Xiaoyao Ford. Zhang Liao and the defenders inflicted a devastating defeat on Sun Quan and his forces.[A 68]

In the winter of 216, Cao Cao staged a military drill in Ye (present-day Handan, Hebei), during which he personally beat a war drum to direct his troops' movements and boost their morale.[B 20] After the drill, he launched another campaign against Sun Quan and arrived in Juchao (居巢; in present-day Chaohu, Anhui) by spring in the following year. In late March or April 217, he ordered his troops to make camp at the Hao Gorge (郝谿) on the west bank of the Yangtze. Sun Quan had constructed a dock and stationed defences at Ruxu. Both sides clashed at Ruxu and the battle ended with an inconclusive result. Cao Cao withdrew his forces in late April or May 217, leaving behind Xiahou Dun, Cao Ren, Zhang Liao and others to defend Juchao.[A 69]

Campaign against Zhang Lu (215)

In early 215, Cao Cao launched a campaign against Zhang Lu in Hanzhong Commandery. He first sent Zhang He, Zhu Ling and others to lead an army to attack the Di tribes blocking the way in Wudu Commandery (武都郡; around present-day Longnan, Gansu). They defeated and massacred the Di population in Hechi County (河池縣; northwest of present-day Pingliang, Gansu).[A 70]

By mid 215, Cao Cao's army reached Yangping Pass (陽平關; in present-day Ningqiang County, Shaanxi) after making a long and arduous journey across mountainous terrain. When his soldiers started complaining, Cao Cao announced that he would remember them for their contributions to encourage them to move on.[B 21] Zhang Lu ordered his younger brother Zhang Wei (張衛) and subordinate Yang Ang (楊昂) to lead troops to defend the pass, making use of the mountainous terrain to counter Cao Cao's advances. Cao Cao was unable to overcome the enemy after launching assaults so he withdrew to put them off guard. One night, Cao Cao secretly ordered Xie Biao (解忄剽) and Gao Zuo (高祚) to lead a sneak attack on Yangping Pass. Zhang Lu retreated to Bazhong, when he heard that Yangping Pass had been taken. Cao Cao proceeded to occupy Nanzheng County, the capital of Hanzhong Commandery.[A 71]

After taking control of Hanzhong Commandery, Cao Cao made some administrative changes to the commandery, such as redrawing boundaries and appointing some administrators to govern the newly formed commanderies. In late 215, Zhang Lu led his followers out of Bazhong and voluntarily submitted to Cao Cao, who accepted his surrender and granted him a marquis title. Around the time, Liu Bei had recently seized control of Yi Province (covering present-day Sichuan and Chongqing) from its governor Liu Zhang and occupied Bazhong after Zhang Lu left. Cao Cao ordered Zhang He to lead a force to attack Liu Bei, but Zhang He lost to Liu Bei's general Zhang Fei at the Battle of Baxi. About a month after Zhang Lu's surrender, Cao Cao left Nanzheng County and headed back to Ye (present-day Handan, Hebei), leaving behind Xiahou Yuan to guard Hanzhong Commandery.[A 72]

War with Liu Bei in Hanzhong (217–219)

In the winter of 217, Liu Bei sent Zhang Fei, Ma Chao, Wu Lan (吳蘭) and others to garrison at Xiabian (下辯; northwest of present-day Cheng County, Gansu). Cao Cao ordered Cao Hong to lead an army to resist the enemy. In the spring of 218, Cao Hong defeated Wu Lan and killed his deputy Ren Kui (任夔). In April or May 218, Zhang Fei and Ma Chao retreated from Hanzhong Commandery while Wu Lan was killed by Qiangduan (強端), a Di chieftain from Yinping Commandery (陰平郡; around present-day Wen County, Gansu).[A 73]

In August or early September 218, Cao Cao staged a military drill and launched a campaign against Liu Bei. His army reached Chang'an in October. In the meantime, Liu Bei's forces had already engaged Cao Cao's forces, under Xiahou Yuan's command, in Hanzhong Commandery. In early 219, Xiahou Yuan was killed in action at the Battle of Mount Dingjun against Liu Bei's general Huang Zhong. In April 219, Cao Cao led his forces from Yangping Pass (陽平關; in present-day Ningqiang County, Shaanxi) towards Hanzhong via Xie Valley (斜谷). Liu Bei made use of the geographical advantage he had – mountainous terrain – to hold off Cao Cao.[A 74] That July, Cao Cao withdrew his forces back to Chang'an.[A 75]

Battle of Fancheng (219-220)

In the autumn of 219, Cao Cao ordered Yu Jin to lead seven armies to reinforce Cao Ren, who was under siege by Liu Bei's general Guan Yu at Fancheng (樊城; present-day Fancheng District, Xiangyang, Hubei). However, due to heavy rains, the Han River burst its banks and the seven armies were destroyed in the flood. Guan Yu captured Yu Jin, executed his subordinate Pang De, and continued to press on the attack on Cao Ren. Cao Cao ordered Xu Huang to lead another army to help Cao Ren.[A 76]

At the same time, Cao Cao also contemplated relocating the imperial capital from Xuchang further north into Hebei to avoid Guan Yu, but Sima Yi and Jiang Ji told him that Sun Quan would become restless when he heard of Guan Yu's victory. They suggested to Cao Cao to ally with Sun Quan and enlist his help in hindering Guan Yu's advances. In return, Cao Cao would recognise the legitimacy of Sun Quan's claim over the territories in Jiangdong. In this way, the siege on Fancheng would automatically be lifted. Cao Cao heeded their suggestion.[A 77]

Cao Cao arrived in Luoyang in the early winter of 219 after returning from his failed campaign against Liu Bei in Hanzhong Commandery. Later, he led an army from Luoyang to relief Cao Ren, but turned back before he reached his destination because he received news that Xu Huang had already defeated Guan Yu and lifted the siege on Fancheng.[A 78]

In the spring of 220, Cao Cao returned to Luoyang and remained there. In the meantime, Sun Quan had sent his general Lü Meng and others to launch a stealth assault on Liu Bei's territories in Jing Province while Guan Yu was away on the Fancheng campaign, and they succeeded in conquering Guan Yu's key bases in Jing Province – Gong'an County and Jiangling County. Guan Yu, having lost his bases and forced to withdraw from Fancheng, was eventually surrounded by Sun Quan's forces and captured in an ambush and executed. Sun Quan sent Guan Yu's head to Cao Cao,[A 79] who arranged a noble's funeral for Guan Yu and had his head buried with full honours.[B 22]

Titles of nobility (213–220)

Duke of Wei

Cao Cao returned to Ye (present-day Handan, Hebei) in the spring of 212 after the Battle of Tong Pass. Emperor Xian granted him special privileges similar to those awarded to Xiao He by Emperor Gao. Cao Cao did not have to have his name announced, did not have to walk in quickly, and had permission to carry a ceremonial sword and wear shoes when he entered the imperial court. fourteen counties from five different commanderies were segregated from their respective commanderies and placed under the jurisdiction of Wei Commandery (魏郡; around present-day Handan, Hebei).[A 80]

In 213, after Cao Cao returned from the Battle of Ruxu against Sun Quan, Emperor Xian issued a decree abolishing the fourteen provinces system and replacing it with an older nine provinces system. About a month after Cao Cao returned to Ye, Emperor Xian sent Chi Lü (郗慮) as an emissary to enfeoff Cao Cao as the Duke of Wei (魏公). After Cao Cao refused the customary three times, the emperor sent a thirty-person delegation of officials to make a fourth offer of enfeoffment, which was accepted.[B 23] In August 213, an ancestral temple and the sheji (altars for worshipping the gods of soil and grain) were built in Cao Cao's dukedom. Later, Emperor Xian sent a six person delegation led by high ranking government minister Wang Yi (王邑) to present betrothal gifts of jade, silk, and other precious items to Cao Cao as part of an arrangement for three of Cao Cao's daughters to become the emperor's concubines: Cao Jie, Cao Hua, and Cao Xian.[B 24][A 81] It is to be understood that these grants of honours, titles, prerogatives, and imperial marriage arrangements were not of the emperor's own initiative, but orchestrated by Cao Cao and his staff, who controlled the Imperial Secretariat. As early as the Book of the Later Han, few historians offer Cao Cao the veneer of legitimacy in his appointments and enfeoffments, forgoing mention of the emperor and instead describing the actions as a personal decision.[19]

In October 213, Cao Cao ordered the construction of the Golden Tiger Platform (金虎臺) and a watercourse linking the Zhang River and White Canal (白溝). A month later, he divided Wei Commandery into the east and west divisions, each governed by a Commandant. In December, he established a ducal secretariat in his fief along with the offices of Palace Attendants and the Six Ministers.[A 82]

In late January or February 214, Cao Cao attended a ceremony, known as ji li (籍禮), to promote agriculture.[lower-alpha 13][20] In late March or April, Emperor Xian sent Yang Xuan (楊宣) and Pei Mao (裴茂) as emissaries[B 25] to present Cao Cao with a golden official seal with a red ribbon and a yuanyou guan (遠遊冠),[lower-alpha 14] placing Cao (who was still only a duke then) in a position above other nobles.[A 83]

In December 214 or January 215, Empress Fu Shou wrote a secret letter to her father Fu Wan (伏完) to tell him that Emperor Xian resented Cao Cao for the execution of Dong Cheng. The contents of the letter were hateful. The incident was exposed and Empress Fu was deposed and executed, her family exiled.[A 84]

In January or February 215, Cao Cao went to Meng Ford (孟津), a historically important spot near the site of the ancient Battle of Muye. Emperor Xian allowed him to make a maotou (旄頭; a banner decorated with animals' tails, typically reserved for the emperor) and erect a zhongju (鍾虡; a bell pendant stand) in his ducal palace. Cao Cao later issued two official statements and established a licaoyuan (理曹掾; a justice ministry).[A 85]

In the spring of 215, Emperor Xian instated Cao Cao's daughter, Cao Jie, as the new empress. Cao Cao visited four commanderies and merged them into a new commandery – Xinxing Commandery (新興郡; 'The Newly Rising Commandery') – with one of the counties as the commandery capital. In winter, while he was away in Hanzhong Commandery, Cao Cao created the titles of the Five Counsellors and nominal marquis titles for the first time, alongside the original six grades of marquis ranks.[lower-alpha 15] These new titles were awarded to Cao Cao's men who had made contributions in battle during the campaign against Zhang Lu, as Cao Cao had promised them earlier.[A 86]

In February or early March 216, Cao Cao returned to Ye (present-day Handan, Hebei) after a successful campaign against Zhang Lu in Hanzhong Commandery.[A 87] Two months later, he attended another ji li (籍禮) ceremony.[A 88]

King of Wei

In June 216, Emperor Xian promoted Cao Cao from a duke to a vassal king under the title "King of Wei" (魏王). Cao Cao summoned Sima Fang, who had recommended him to be the Commandant of the North District in Luoyang early in his career, to meet him in Ye, where they had a chat.[lower-alpha 16] Later, the Wuhuan chanyu Pufulu (普富盧) from Dai Commandery (代郡; northwest of present-day Yu County, Hebei) led his various subjects to Ye to pay tribute to Cao Cao. Around the same time, Emperor Xian instated one of Cao Cao's daughters as a princess and granted her a fief with some taxable households. In August 216, the southern Xiongnu chanyu Huchuquan brought along his subjects to pay tribute to Cao Cao, who treated them like guests. Huchuquan remained in Cao Cao's vassal kingdom and placed his deputy in charge of his Xiongnu domain. In September, Cao Cao promoted Zhong Yao from the position of Grand Judge (大理) under the Han central government to the Royal Chancellor (相國) of his vassal kingdom.[A 89] He also established the offices of the Minister of Ancestral Ceremonies (奉常) and Minister of the Royal Clan (宗正) in his vassal kingdom.[B 28]

In late May or June 217, Emperor Xian allowed Cao Cao to have his personal jingqi (旌旗; a banner) and have imperial guards clear the path when Cao travelled around. In late June or July, Cao Cao had a pangong (泮宮)[lower-alpha 17] constructed. In July or August, Hua Xin was appointed as Imperial Counsellor (御史大夫). Cao Cao also established the office of the Minister of the Guards (衞尉) in his vassal kingdom.[B 29] In November or December, Emperor Xian granted more ceremonial privileges to Cao Cao: have twelve fringes of pearls on his crown; ride in a golden carriage pulled by six horses; have five other carriages to accompany his main carriage when he travelled around. Cao Cao's son, Cao Pi, who was serving as General of the Household for All Purposes (五官中郎將) in the Han imperial court, was designated as the Crown Prince (太子) of Cao Cao's vassal kingdom.[A 90]

In February or early March 218, the imperial physician Ji Ben, along with Geng Ji (耿紀), Wei Huang (韋晃) and others, started a rebellion in the imperial capital Xuchang and attacked the camp of Wang Bi (王必), a chief clerk under Cao Cao. Wang Bi suppressed the revolt with the aid of Yan Kuang (嚴匡), an Agriculture General of the Household (典農中郎將).[A 91]

In late July or August 219, Cao Cao designated his formal spouse, Lady Bian, as his queen consort.[A 92] Some months later, Sun Quan wrote to Cao Cao, expressing his desire to submit to Cao Cao and urging Cao Cao to take the throne from Emperor Xian. Cao Cao showed Sun Quan's letter to his subordinates and remarked: "This kid wants me to put myself on top of a fire!" Chen Qun, Huan Jie and Xiahou Dun also urged Cao Cao to usurp the imperial throne from Emperor Xian, but Cao Cao refused.[B 30][B 31]

Death (220)

Cao Cao died on 15 March 220 in Luoyang at the age of 66 (by East Asian age reckoning). He was granted the posthumous title "King Wu" (武王; "martial king") by Emperor Xian. His will instructed that he be buried near Ximen Bao's tomb in Ye without gold and jade treasures, and that his subjects on duty at the frontier were to stay in their posts and not attend the funeral as, in his own words, "the country is still unstable".[A 93] He was buried on 11 April 220 in the Gaoling (高陵; "high mausoleum").[A 94] In December 220 or early January 221, after Cao Pi forced Emperor Xian to abdicate the throne in his favour and established the state of Cao Wei, he granted his father the posthumous title "Emperor Wu" (武皇帝; "Martial Emperor")[A 95] and the temple name "Taizu" (太祖; "Grand Ancestor").[Z 2]

Cao Cao Mausoleum

On 27 December 2009, the Henan Provincial Cultural Heritage Bureau reported the discovery of Cao Cao's tomb in Xigaoxue Village, Anyang County, Henan. The tomb, covering an area of 740 square metres, was discovered in December 2008 when workers at a nearby kiln were digging for mud to make bricks. Its discovery was not reported and the local authorities knew of it only when they seized a stone tablet carrying the inscription 'King Wu of Wei' – Cao Cao's posthumous title – from grave robbers who claimed to have stolen it from the tomb. Over the following year, archaeologists recovered more than 250 relics from the tomb. The remains of three persons – a man in his 60s, a woman in her 50s and another woman in her 20s – were also unearthed and are believed to be those of Cao Cao, one of his wives, and a servant.[21]

Since the discovery of the tomb, there have been many sceptics and experts who pointed out problems with it and raised doubts about its authenticity.[22] In January 2010, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage legally endorsed the initial results from research conducted throughout 2009 suggesting that the tomb was Cao Cao's.[23] However, in August 2010, 23 experts and scholars presented evidence at a forum held in Suzhou, Jiangsu to argue that the findings and the artefacts of the tomb were fake.[24] In September 2010, an article published in an archaeology magazine claimed that the tomb and the adjacent one actually belonged to Cao Huan (a grandson of Cao Cao) and his father Cao Yu.[25]

In 2010, the tomb became part of the fifth batch of Major Historical and Cultural Sites Protected at the National Level in China.[26] A museum was opened at the site in April 2023.[27]

Family

According to historical records, Cao Cao had 15 wives and concubines, 25 sons, six daughters and two adopted sons. His first formal spouse was Lady Ding, who raised his eldest son Cao Ang (born to his concubine Lady Liu). She fell out with him after Cao Ang's death and effectively separated from him. After Lady Ding left him, Cao Cao designated Lady Bian, one of his concubines, as his new formal spouse and she remained in this position permanently. Among Cao Cao's sons (excluding Cao Ang), the more notable ones are Cao Pi, Cao Zhang, Cao Zhi and Cao Chong, who were, at different points in time, considered as potential candidates to succeed their father. Cao Chong, who was born to Lady Huan, was a child prodigy who devised a method of weighing an elephant by using the principle of buoyancy. Cao Chong died prematurely at the age of 12. Cao Pi, Cao Zhang and Cao Zhi were born to Lady Bian and were known for their individual talents: Cao Pi and Cao Zhi were noted as brilliant writers and poets; Cao Zhang inherited his father's military skills. Cao Pi eventually overcame his two younger brothers in a succession struggle and was chosen to be his father's heir apparent. Three of Cao Cao's daughters – Cao Xian, Cao Jie and Cao Hua – were married to Emperor Xian. Cao Cao's two adopted sons, Qin Lang and He Yan, were conceived from his wives' previous marriages.

Research on Cao Cao's ancestry

Cao Cao was a purported descendant of Cao Shen, a statesman of the early Western Han dynasty. In the early 2010s, researchers from Fudan University compared the Y chromosomes collected from a tooth from Cao Cao's granduncle, Cao Ding (曹鼎), with those of Cao Shen and found them to be significantly different. Therefore, the claim about Cao Cao descending from Cao Shen was not supported by genetic evidence.[28] The researchers also found that the Y chromosomes of Cao Ding match those of self-proclaimed living descendants of Cao Cao who hold lineage records dating back to more than 100 generations ago.[29]

Zhu Ziyan, a history professor from Shanghai University, argued that Cao Ding's tooth alone cannot be used as evidence to determine Cao Cao's ancestry. He was sceptical about whether those who claim to be Cao Cao's descendants are really so because genealogical records dating from the Song dynasty (960–1279) are already so rare in the present day, much less those dating from the Three Kingdoms era (220–280). Besides, according to historical records, Cao Ding was a younger brother of the eunuch Cao Teng, who adopted Cao Cao's biological father, Cao Song. Therefore, Cao Cao had no blood relations with Cao Ding; i.e., Cao Ding was not Cao Cao's real granduncle. Zhu Ziyan mentioned that Fudan University's research only proves that those self-proclaimed descendants of Cao Cao are related to Cao Ding; it does not directly relate them to Cao Cao.[30]

Personal life

Cao Cao was known to be frugal and modest in his daily life, showing no particular interest in aesthetic appeal. The clothes and shoes he wore at home were plain and simple. When the folding screens and curtains in his house were damaged, he simply had them mended instead of replaced. He relied on only mattresses and blankets for warmth, and had no decorative ornaments at home.[B 32] When he met guests, he wore a simple hat and clothes made of raw silk and had a pouch containing a handkerchief and other small items attached to his belt. Outside of his work life, Cao Cao was known to behave in a frivolous and carefree manner. When he chatted with people, he spoke casually, occasionally poked fun at others, and shared everything on his mind. Once, during a meal, he was so amused that he laughed until he knocked his head into the dishes and soiled his face and clothing.[B 33]

Cao Cao's low regard for material wealth influenced not only his personal life, but also his political and military careers and other aspects of his life. In the late Eastern Han dynasty, fujins (幅巾; similar to bokgeon), especially those made of silk, became popular among the scholar-gentry and upper class because they felt that wearing a fujin made one look cultured and refined. Cao Cao, however, disapproved of wearing expensive headgear as he felt that the country lacked monetary resources due to chaos and famines, hence he advocated replacing silk fujins with the older bians (弁; a type of cap) made of leather. He also suggested the use of colours (instead of material) to distinguish status in the military. His ideas were implemented. He also invented a type of hat, the qia (帢), for casual wear.[B 34] He felt that it was a pity to have very extravagant arrangements in weddings, so, when his daughter got married, she was dressed modestly and had no more than 10 ladies-in-waiting to accompany her.[B 35] After winning battles, he awarded the spoils of war to his men who had made contributions. He heavily rewarded those who deserved to be rewarded; undeserving people who expected to receive something from him had their hopes dashed. When others presented gifts to him, he shared those gifts with his subordinates. He felt that it was of no benefit to own many possessions because such things would eventually wear out. He personally prepared the clothes he would wear at his funeral and the items he would be buried with, which were sufficient to fill up just four trunks.[B 36]

Interests and hobbies

Cao Cao was known to be very skilled in hand-to-hand combat. When he was still a youth, he once broke into the eunuch Zhang Rang's personal chambers but was discovered. Armed with only a short ji halberd, he brandished the weapon at the guards as he slowly retreated and eventually climbed over the wall and escaped.[B 37] He also enjoyed hunting and once shot down 63 pheasants in a single day during a hunting expedition in Nanpi County.[B 38]

Cao Cao was very fond of reading books, especially military classics and treatises. Apart from writing military journals and annotating Sun Tzu's The Art of War, he also collected various military books and compiled extracts from them. His works were spread around. He also gave out new reading materials to his officers when they went to battle. He never neglected reading throughout his military career of over 30 years.[B 39][B 40] When Sun Quan encouraged his general Lü Meng to take up scholarly pursuits, he cited Cao Cao as an example: "Mengde agrees that he is already old but he never gives up on learning."[B 41]