Languages of Sweden

Swedish is the official language of Sweden and is spoken by the vast majority of the 10.23 million inhabitants of the country. It is a North Germanic language and quite similar to its sister Scandinavian languages, Danish and Norwegian, with which it maintains partial mutual intelligibility and forms a dialect continuum. A number of regional Swedish dialects are spoken across the country. In total, more than 200 languages are estimated to be spoken across the country, including regional languages, indigenous Sámi languages, and immigrant languages.[2]

| Languages of Sweden | |

|---|---|

| Official | Swedish |

| Indigenous | (Officially recognised) Sámi languages, Swedish. |

| Regional | (Unofficial languages / Dialects) South Swedish, Götamål, Svealand Swedish, Norrland, and Gutnish, among others. |

| Minority | (Officially recognised) Finnish, Meänkieli, Romani, Yiddish |

| Immigrant | Arabic, Serbo-Croatian, Greek, Kurdish, Persian, Polish, Spanish, Somali[1] |

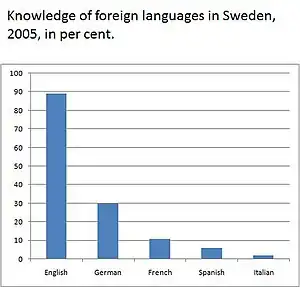

| Foreign | English (89%) German (30%) French (11%) |

| Signed | Swedish Sign Language |

| Keyboard layout | |

| Source | ebs_243_en.pdf (europa.eu) |

In 2009, the Riksdag passed a national language law recognizing Swedish as the main and common language of society, as well as the official language for "international contexts". The law also confirmed the official status of the five national minority languages — Finnish, Meänkieli, Romani, Sámi languages and Yiddish — and Swedish Sign Language.

History

For most of its history, Sweden was a larger country than today. At its height in 1658, the Swedish Empire spread across what is currently Finland and Estonia and into parts of Poland, Russia, Latvia, Germany, Denmark, and Norway. Hence, Sweden's linguistic landscape has historically been very different from its current context.

Swedish evolved from Old Norse around the 14th and 15th century. Swedish dialects were generally much more diverse in the past than they are today. Since the 20th century, Standard Swedish has prevailed throughout the country. The Scandinavian languages constitute a dialectal continuum and some of the traditional Swedish dialects could equally be described as Danish (Scanian) or Norwegian dialects (Jämtlandic).

Finnish was the majority language of Sweden's eastern parts, though it was almost exclusively a spoken language. Parts of Finland are also home to a significant Swedish-speaking minority, including Åland, many of whom speak the Finland Swedish dialect. Finnish became a minority language in western Sweden as many Finnish speakers migrated there for economic reasons.

Estonian was the language of the majority in Swedish Estonia but the province, like Finland, hosted a Swedish-speaking minority and a more significant minority of Germans.

In medieval Sweden, the Low German language played an important role as a commercial language, serving as the lingua franca of the Hanseatic league. As such, Low German influenced Swedish and other languages in the region considerably. In medieval Stockholm, half the population were Low German speakers.[3] Low German was also spoken in the 17th-century Swedish territories along the southern Baltic Coast in Swedish Pomerania, Bremen-Verden, Wismar and Wildeshausen, as well as by the Baltic Germans in Estonia and Swedish Livonia. Livonia was also inhabited by Latvians, Estonians and Livonians.

In Swedish Ingria, Finnish, Ingrian and Votian were spoken along with Swedish.

Latin, as the language of the Catholic Church, was introduced to Sweden with the Christianization of Sweden, around AD 1000. As in most of Europe, Latin remained the lingua franca and scholarly language of the educated communities for centuries in Sweden. For instance, Carl Linnaeus's most famous work, Systema Naturae, published in 1735, was written in Latin.

During the 18th century, French was the second language of Europe's upper classes and Sweden was no exception. The Swedish aristocracy often spoke French among themselves and code-switching between French and Swedish was common. The Swedish King Gustav III was a true Francophile and French was the common language at his court. In 1786, Gustav III founded the Swedish Academy to promote and advance the Swedish language and literature.[4]

Aside from what is currently Norway, Sweden largely obtained its current borders in 1809, when it lost its eastern part (Finland) to the Russian Empire. Sweden largely lost its overseas possessions over time, with Swedish Pomerania being ceded to Denmark in exchange for Norway and Guadeloupe was returned to France in 1814. As a consequence, Sweden became a rather homogeneous country with the exceptions of the indigenous Sámi people and the Finnish-speaking Tornedalians in the northernmost parts of the country.

During the 19th century, Sweden became more industrialised, resulting in important demographic changes. The population doubled and people moved from the countryside to towns and cities. As a consequence of this and factors such as generalised education and mass media, traditional dialects began to make room for the standard language (Standard Swedish). During the same period and until the 1970s, Sweden applied a Swedification policy that limited schooling to Swedish-language instruction and actively discouraged the use of other languages.[5]

As in the rest of Europe and much of the world, the English has grown as an important foreign language in Sweden, especially since the Allied victory in World War II. During the second half of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century, Sweden has received great numbers of immigrants who speak languages other than Swedish (see: "Immigrant languages" below). It is unclear to what degree these communities will hold on to their languages and to what degree they will assimilate.

In 2009, the Riksdag passed the Language Law (Språklag SFS 2009:600), which contains provisions concerning the Swedish language, the five national minority languages and Swedish Sign Language. Among its provisions is a general mandate to safeguard the Swedish language, linguistic diversity in Sweden, and individuals' access to language.[6]

Swedish

The Kingdom of Sweden is a nation-state for the Swedish people and as such the national language is held in high regard. Of Sweden's roughly 10 million people, almost all speak Swedish as at least a second language and the majority as a first language (7,825,000, according to SIL's Ethnologue). Swedish is also an official language in Finland where it is spoken by a large number of Swedish-speaking Finns. The language is also spoken to some degree by ethnic Swedes living outside Sweden, for example, just over half a million people of Swedish descent in the United States speak the language, according to Ethnologue.

The Language Law of 2009 recognizes Swedish as the main and common language of society, as well as being the official language in "international contexts".[6]: 4,5,14

Dialects

Norrland Finland Swedish Gutnish

Norwegian Dialectal Influence

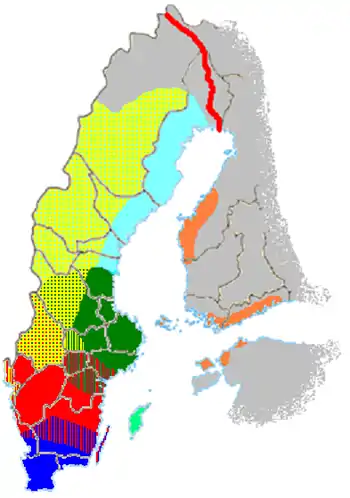

A number of Swedish dialects exist and are generally classified into six groups, called sockenmål in Swedish: South Swedish, Götamål, Svealand Swedish, Norrland, Finland Swedish, and Gutnish. As North Germanic languages these dialects all grew out of Old Norse, but under differing influences as the language split along East and West Scandinavian branches. In western Sweden, many local dialects, such as Jämtlandic and Dalecarlian, show greater influence from the West Scandinavian branch of Old Norse and Norwegian. Some dialects are divergent enough from standard Swedish to be considered separate languages.

Dalecarlian

The Dalecarlian dialect group of Dalarna County varies significantly, ranging from the variations in the northwest of the county similar to the neighboring East Norwegian Østerdalsmål dialect to versions more similar to Swedish. The Älvdalen Municipality has a population of about 1,500 speakers of the Elfdalian Dalecarlian dialect.[7]

Gutnish

Modern Gutnish or Gotlandic exists as a spoken language in Gotland and Fårö. While influenced by Swedish, Gutnish is descended from Old Gutnish, which evolved as a separate branch of Old Norse.

Jämtlandic

Spoken mainly in Jämtland, but with a scattered speaker population throughout the rest of Sweden, Jämtlandic or Jämska is a West Scandinavian language and part of the Norrland sockenmål with 95% lexical similarity to Norwegian and Swedish, but is generally more archaic. It has a native speaker population of 30,000.[8]

Scanian

Spoken in the Swedish province of Scania, Scanian is considered by some a dialect of Danish,[9] and the related Bornholmsk dialect spoken on the Baltic island of Bornholm, is considered an East Danish dialect. Historically, Bornholmsk and Scanian split after Denmark ceded Scania to Sweden in 1658.

Recognised minority languages

In 1999, the Minority Language Committee of Sweden formally declared five languages as official minority languages of Sweden: Finnish, Meänkieli (also known as Tornedal, Tornionlaaksonsuomi or Tornedalian), Romani, Sámi languages (in particular Lule, Northern, and Southern Sámi), and Yiddish.[10] The Language Law of 2009 confirms the recognition of these five languages as "national minority languages".[6]: 7,8 This status enshrines the right of speakers of these languages to receive schooling and other services in their language.

Finnish

As of 2009, there were about 470,000 Finnish-speakers in Sweden.[11] Finnish, a Uralic language, has long been spoken in Sweden (the same holds true for Swedish in Finland, see Finland-Swedes, Åland), as Finland was part of the Swedish kingdom for centuries. Ethnic Finns (mainly first- and second-generation immigrants) constitute up to 5% of the population of Sweden. A high concentration of Finnish-speakers (some 16,000) resides in Norrbotten.

Meänkieli

Meänkieli is a Finnic language related to Finnish and Kven. Spoken by the Tornedalian people, it is mutually intelligible with Finnish, but has a higher number of Swedish loan words; it is sometimes considered a dialect of Finnish. Meänkieli is mainly used in the municipalities of Gällivare, Haparanda, Kiruna, Pajala and Övertorneå, all of which lie in the Torne Valley. Between 40,000 and 70,000 people speak Meänkieli as their first language.

Sámi languages

The Sámi people (formerly known as Lapps) are a people indigenous to Scandinavia and the Kola peninsula (see Sápmi) who speak a related group of languages, three of which — Lule, Northern, and Southern Sámi — are spoken in Sweden.[12] Like Finnish and Meänkieli, Sámi languages are Uralic languages; however, prolonged exposure to Germanic-language-speaking neighbors in Sweden and Norway causes them to have a large number of Germanic loanwords not found in other Uralic languages. Between 15,000 and 20,000 Sámi people live in Sweden of whom 9,000 speak a Sámi language. In Sweden, the largest concentrations of Sámi-language speakers are found in the municipalities of Arjeplog, Gällivare, Jokkmokk, Kiruna, and other parts of Norrbotten.

Romani

Romani (also known as Rromani Ćhib) is a family of Indo-Aryan languages spoken by the Romani people, a nomadic ethnic group originating in northern India. Several dialects of Romani are spoken and Swedish, including the Scandoromani Para-Romani admixture of Scandinavian languages and Romani. Around 90% of Sweden's Romani people speak a form of Romani, meaning that there are approximately 9,500 ćhib speakers. In Sweden, there is no major geographic center for Romani, as there is for Finnish, Sámi, or Meänkieli, but it is considered to be of historical importance by the Swedish government and as such the government is seen as having an obligation to preserve them, a distinction also held by Yiddish.[13] Because of this, the Swedish government has helped develop and publish a significant number of books and educational materials in Romani.[14]

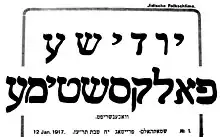

Yiddish

Yiddish is a Germanic language with significant Hebrew and Slavic influence, written with a variant of the Hebrew alphabet (see Yiddish orthography) and, formerly spoken by most Ashkenazic Jews (although most now speak the language of the country in which they live). Although the Jewish population of Sweden was traditionally Sephardic, after the 18th century, Ashkenazic immigration increased bringing with them the Yiddish language (See History of the Jews in Sweden). Like Romani, it is seen by the government as a language of historical importance. The organisation Sällskapet för Jiddisch och Jiddischkultur i Sverige (Society for Yiddish and Yiddish Culture in Sweden) has more than 200 members, many of whom are mother-tongue Yiddish speakers, and arranges regular activities for the speech community and in external advocacy for the Yiddish language.

As of 2009, the Jewish population in Sweden was estimated at around 20,000, about 2,000–6,000 of whom claim to have at least some knowledge of Yiddish. The number of native speakers among these has been estimated by linguist Mikael Parkvall to be 750–1,500. It is believed that virtually all native speakers of Yiddish in Sweden today are adults, and most of them elderly.[15]

Swedish Sign Language

Swedish Sign Language (SSL) is an officially recognized language[6]: 9 and is used by the Deaf community in Sweden. SSL was developed in the early 1800s, possibly with some influence from British Sign Language. It has influenced the development of sign languages in Finland, Portugal, and Eritrea (see Swedish Sign Language family).

Foreign languages

Since the Middle Ages until the end of World War II, Germany was usually the country outside Scandinavia with the closest cultural, commercial and political relations with Sweden. Thus, study of the German language had always been promoted by the Swedish state as the primary foreign language. Many of Sweden's administrative and social institutions, including the education system, were organised along the German and Prussian model, as many Swedish pioneering intellectuals of the 17th century were educated in German universities. This changed after the end of the Second World War, when it was no longer acceptable to emphasise a closer link with defeated Germany.

A majority of Swedes, especially those born after World War II, are able to understand and speak English thanks to trade links, the popularity of overseas travel, a strong American influence, especially in regards to arts and culture, and the tradition of subtitling rather than dubbing foreign television shows and films. English, whether in American, Commonwealth (Australian, Canadian, and Kiwi) or British dialects, has been a compulsory subject for secondary school students studying natural sciences as early as 1849 and has been a compulsory subject for all Swedish students since 1952, when it replaced German.[18]

Depending on local school authorities, English is currently a compulsory subject from third until ninth grade, and all students continue to study English in secondary school for at least another year. Most students also learn one and sometimes two additional languages; the most popular being German, French and Spanish. From the autumn semester 2014, Mandarin Chinese is proposed as a fourth additional language.[19] Some Danish and Norwegian are also taught as part of Swedish language learning to emphasize differences and similarities between the languages.

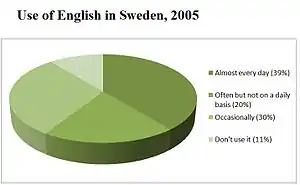

English

There is currently an ongoing debate among linguists whether English should be considered a foreign language, second language or transcultural language in Sweden (and other Scandinavian countries)[20] due to its widespread use in education[21] and society in general.[22][23] This has also triggered opposition: in 2002 the Swedish government proposed an action plan to strengthen the status of Swedish[24][25] and in 2009 Swedish was announced the official language of the country for the first time in its history. Since 2011, Swedes have consistently been ranked among the best non-native English speakers in the world by EF Education First's English Proficiency Index, placing first on the Index in 2012, 2013, 2015 and 2018.[26][27]

Immigrant languages

Like many developed European countries from the late 1940s to the 1970s, Sweden has received tens of thousands of guest workers from countries in Southern Europe and the Middle East. Second- and third-generation Swedes of Southern European or Middle Eastern descent have adopted Swedish as their main tongue or in addition to their immigrant languages, such as Arabic, Bulgarian, Greek, Italian, Bosnian/Serbian/Croatian, and Turkish.

In 2016, language-learning service Duolingo shared first-party statistics which showed that most of the people using the service to study Swedish were actually located in Sweden, and that Sweden-based users were taking the Swedish course for English speakers more than any other course available on the service; the staff determined that both of these facts were a result of Sweden's large immigrant population.[28]

See also

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Sweden |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and Folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Sport |

References

- "kielineuvosto, finska, jidisch, romani, teckenspråk, samiska - Institutet för språk och folkminnen". Sofi.se. 3 February 2007. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

"De största invandrarspråken är arabiska, turkiska, persiska, spanska, grekiska och ex-jugoslaviska språk"; "The largest immigrant languages are Arabic, Turkish, Persian, Spanish, Greek and ex-Yugoslav languages". Note that Finnish in deed is one of the most spoken immigrant languages but not classified as such by the Institutet för språk och folkminnen since it has acquired status as an official minority language.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Landes, David (1 July 2009). "Swedish becomes official 'main language". The Local. Stockholm, Sweden. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Stockholm grundas". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-05-03.

- Haugen, Einar; Thomas L., Markey (2012). The Scandinavian Languages: Fifty Years of Linguistic Research (1918 - 1968). Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-087066-4. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Kent, Neil (2019). The Sámi Peoples of the North: A Social and Cultural History. London, England: Hurst. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-78738-172-8. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Språklag" [Language Law]. Article 2009:600, Law of 28 May 2009 (in Swedish). Sveriges Riksdag.

- "Ethnologue report for language code:DLC". Archived from the original on 2007-03-23. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- "Ethnologue report for language code:JMK". Archived from the original on 2007-02-12. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- "Ethnologue report for language code:scy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-03. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- Hult, Francis M. (2004). "Planning for multilingualism and minority language rights in Sweden". Language Policy. 3 (2): 181–201. doi:10.1023/B:LPOL.0000036182.40797.23. S2CID 144303516.

- "Tilastojen kertomaa: RUOTSINSUOMALAISET 2009 - Sisuradio" [Statistics: SWEDISH FINNISH 2009 - Sisuradio]. Sveriges Radio (in Swedish). 28 April 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- The critically endangered languages of Pite and Ume Sámi are also spoken in Sweden by a handful of people.

- "אַ סך-הכּל פֿון דער פּאָליטיק פֿון דער" (PDF). Manskligarattigheter.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Matras, Yaron; Tenser, Anton (2019). The Palgrave Handbook of Romani Language and Linguistics. Stuttgart, Germany: Springer Nature. p. 549. ISBN 978-3-030-28105-2. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Parkvall, Mikael (2009). "Sveriges språk. Vem talar vad och var?" [Sweden's languages. Who speaks what and where?] (PDF). Rapporter från Institutionen för lingvistik vid Stockholms universitet (in Swedish). pp. 68–72.

- "Europeans and their Languages" (PDF). Ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

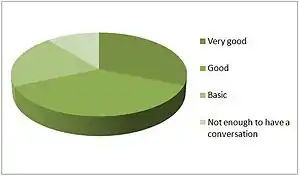

- "Europeans and their Languages" (PDF). Special Eurobarometer 243 / Wave 64.3 - TNS Opinion & Social. European Commission. February 2006. Retrieved May 3, 2011. According to this Eurobarometer survey, 89% of respondents in Sweden indicated that they know English well enough to have a conversation (p. 152). Of these 35% had a very good knowledge of the language, 42% had a good knowledge and 23% had basic English skills (p. 156).

- "English spoken — fast ibland hellre än bra" (in Swedish). Lund University newsletter. July 1999. Archived from the original on 2011-04-30.

- Kinesiska införs som språkval, Lärarnas Tidning, 2012-12-03 (Swedish)

- Sveriges språk, vem talar vad och var Mikael Parkvall, Stockholm University p.100 Men är engelska verkligen ett främmande språk?

- Hult, Francis M. (2017). "More than a lingua franca: Functions of English in a globalised educational language policy". Language, Culture and Curriculum. 30 (3): 265–282. doi:10.1080/07908318.2017.1321008. S2CID 151994775.

- Hult, Francis M. (2012). "English as a Transcultural Language in Swedish Policy and Practice". TESOL Quarterly. 46 (2): 230–257. doi:10.1002/tesq.19.

- Hult, Francis M. (2010). "Swedish television as a mechanism for language planning and policy". Language Problems and Language Planning. 34 (2): 158–181. doi:10.1075/lplp.34.2.04hul.

- Regeringskansliet, Regeringen och (20 September 2017). "Government.se". Regeringskansliet. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Hult, Francis M. (2005). "A Case of Prestige and Status Planning: Swedish and English in Sweden". Current Issues in Language Planning. 6: 73–79. doi:10.1080/14664200508668274. S2CID 145734375.

- "Swedes 'best in the world' at English - again". Thelocal.se. 2013-11-07. Retrieved 2017-08-11.

- "EF EPI 2020 – Sweden". www.ef.edu. EF Education First. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- Pajak, Bozena (May 5, 2016). "Which countries study which languages, and what can we learn from it?". Duolingo Blog. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- "Swedish". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "United States". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Dieter W. Halwachs. "Speakers and Numbers" (PDF). Romani.uni-graz.at. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- "Här är 20 största språken i Sverige". Språktidningen. 28 March 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

External links

- Languages in Sweden

- Språklag (2009:600) [Language Law] text from rkrattsbaser.gov.se