Eretna

ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Eretna (died February or March 1352)[lower-alpha 2] was the first sultan of the Eretnids, reigning between 1343–1352 in central and eastern Anatolia. Initially an officer in the service of Chupan and his son Tīmūrtāsh, he migrated to Anatolia following the latter's appointment as the Ilkhanid governor of the region. He took part in his master Tīmūrtāsh's campaigns to subdue the Turkoman chiefs of the western periphery of the peninsula. This was cut short by Tīmūrtāsh's downfall, after which Eretna went into hiding. Upon the dissolution of the Ilkhanate, he aligned himself with the Jalayirid leader Hasan Buzurg, who eventually left Anatolia for Eretna to govern when he returned east to clash with the rival Chobanids and other Mongol lords. Eretna later sought recognition by the Mamluk Egypt to consolidate his power, although he played a delicate game of alternating his allegiance between the Mamluks and the Mongols. In 1343, he declared independence as the sultan of his domains. His reign was largely described to be prosperous with his efforts to maintain order in his realm such that he was known as Köse Peyghamber (lit. 'the beardless prophet').

| Eretna | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sultan | |||||

Silver coin minted in the name of Eretna in 1351 in Erzincan. It includes an inscription in the Uyghur script that reads sultan adil.[1] | |||||

| Sultan of the Eretnids | |||||

| Reign | 1343–1352[lower-alpha 1] | ||||

| Successor | Giyath al-Dīn Muhammad | ||||

| Viceroy of Anatolia | |||||

| Tenure | 1336–1343[lower-alpha 1] | ||||

| Predecessor | Hasan Buzurg | ||||

| Successor | Declared independence | ||||

| Died | February or March 1352 Kayseri, Eretnids | ||||

| Burial | Köşkmedrese, Kayseri | ||||

| Consort |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Eretnid | ||||

| Father | Taiju Bakhshi | ||||

| Mother | Tükälti | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Early life and background

The Ilkhanate emerged in West Asia under Hulagu Khan as part of the division of the Mongol Empire. After half a century, the seventh Ilkhān Ghazan's death marked the height of the state, and while his brother Öljaitü was capable of maintaining the empire, his conversion to Shiism sped up the impending fall and civil war in the region.[2] Eretna's life coincided with this political turmoil, which would eventually make him an heir to the Ilkhanid dominion.[3]

.jpg.webp)

Of Uyghur stock,[4] Eretna was born to Taiju Bakhshi, a trusted follower of the second Ilkhanid ruler Abaqa Khan, and his wife Tükälti.[5] His name Eretna is popularly explained to have originated from the Sanskrit word ratna (रत्न) meaning 'jewel'.[6] This name was common among the Uyghurs following the spread of Buddhism,[3] and Eretna may have come from Buddhist parentage.[7]

The growing influence of Chupan, a Mongol general, who Eretna was likely serving at the time,[3] prompted various commanders such as Qurumushi and Irinjin to conspire a revolt.[8] Eretna's elder brothers Emir Taramtaz and Suniktaz also joined this revolt, possibly because Chupan refused to grant them important positions due to his Sunni belief that conflicted with Eretna's brothers' Shiite sect.[8] In May–June 1319, the revolt was crushed near Zanjan River.[9] The same year, Taramtaz was executed by Abū Saʿīd along with his brother Suniktaz for joining the rebellion of Qurumushi and Irinjin in 1319.[10] Eretna migrated to Anatolia following his brothers' deaths[11] and his new master (and Chupan's son) Tīmūrtāsh's appointment as the Ilkhanid governor of the region by Ilkhān Abū Saʿīd[3] and Chupan.[12]

Rise to power

Similar to other emirs, Eretna's master Tīmūrtāsh eventually rebelled against the Ilkhanate in 1323,[12] during which Eretna went into hiding.[3] However, the Ilkhān's weak authority and Tīmūrtāsh's father Chupan's influence over the state led to the pardoning of Tīmūrtāsh and the restoration of his position as the governor of Anatolia. He later led an extensive series of campaigns against the Turkoman emirates in Anatolia.[12] Tīmūrtāsh sent Eretna to seize control of Karahisar in August 1327.[13] Eretna further manipulated the Konya-based Mevlevi dervish Ulu Arif Chelebi's son Chelebi ʿAbid as a divine intermediary to subdue and gather the Turkoman commanders of the peripheral regions under the rule of the self-proclaimed messiah, Tīmūrtāsh.[14] Upon the news of his brother Demasq Kaja's death on 24 August 1327, Tīmūrtāsh retreated to Kayseri,[13] and following his father's death, he fled to Mamluk Egypt in December while also planning to come into terms with Abū Saʿīd.[15] He was later killed on the orders of the Mamluk sultan.[12] Fearing punishment during Tīmūrtāsh's absence, Eretna took refuge in the court of Badr al-Dīn Beg of Karaman.[11] Tīmūrtāsh was replaced by Emir Muhammad from the Oirat tribe, who was the uncle of Abū Saʿīd.[16]

Eretna was later involved in a plot against the Ilkhān in 1334 but received a pardon and returned to Anatolia from the Ilkhanid court in Iran.[15] With Abū Saʿīd's death in 1335, the Ilkhanid period practically came to an end, leaving its place to continuous wars between several warlords from princely houses, namely the Chobanids and Jalayirids.[2] Back west, Eretna came under the suzerainty of the Jalayirid viceroy of Anatolia, Hasan Buzurg[3] but had already established his supremacy in the region to a considerable degree.[15]

Hasan Buzurg left Eretna as his deputy in Anatolia when he departed east to oppose the Oirat chieftain Ali Padishah's attempt to occupy the throne. Eretna was officially appointed as the governor of Anatolia by Hasan Buzurg following his victory against Ali Padishah.[13] However, Hassan Kuchak rose in the Ilkhanid domains quickly in 1338.[17] Hassan Kuchak was the son of Tīmūrtāsh and had effectively become the pretender of his father's legacy. He defeated the Jalayirids near Aladağ and pillaged Erzincan.[18]

Due to constant upheavals in the east, Eretna started seeking the protection of a new and stronger regional power. An old rival to the Mongol Empire and its successors, the Mamluks had long aspired to secure their political presence up north. The arrival of Eretna's embassy in Cairo was a godsend in that regard so that he was confirmed as a "Mamluk governor of Anatolia." On the contrary, Eretna did very little to uphold Mamluk sovereignty, minting coins on behalf of the new Chobanid puppet Suleiman Khan in 1339. Thus, the Mamluks started viewing the rising Turkoman leader Zayn al-Dīn Qarāja of Dulkadir more favorably. Eretna had already lost Elbistan to Qarāja in 1337–8 as well as Darende the next year. Having been robbed of the wealth he had stored in the latter city, Eretna confronted the Mamluk sultan, who brought up his failure to declare Mamluk sovereignty. In return, Eretna finally minted coins for the Mamluks in 1339–40. Still, Eretna was able to gain control of Sivas and Konya from the Karamanids.[19]

Eretna's attempt to be on good terms with the Chobanids was hindered by Hasan Kuchak's capture of Erzurum and siege of Avnik. He still insisted on his obedience to Suleiman Khan, although by 1341, he had gained enough power to be able to issue his coins.[20] 1341 is regarded by some scholars as the year he first declared his independence as it was when he first used the title sultan in his coins. Though, he sent his ambassadors to the new Mamluk sultan to secure his status as a na'ib. This elicited a new expedition by Hasan Kuchak in Eretna's lands.[21][22]

Choosing to stay in Tabriz, Hasan Kuchak dispatched his army to Anatolia under Suleiman Khan's command. This force included experienced commanders such as Bayanjar's son Abdul, Yaqub Shah, and Qoch Hussain. Eretna promptly gathered an army of Mamluk forces, Mongols, and local Turks. The battle took place in the plain of Karanbük (between Sivas and Erzincan) in September–October 1343. Eretna initially faced a defeat. While Suleiman Khan's forces were busy with looting and pursuing the remainder of enemy, Eretna hid near the opposite side of a hill. When Suleiman Khan appeared with a small number of troops, as the rest of the forces were disorganized, Eretna attacked. The Chobanid army disintegrated when Suleiman Khan fled the scene. Eretna's victory was unexpected for most actors in the region.[23] This victory resulted in Eretnid annexation of Erzincan and several cities further east well as the start of Eretna's independent reign.[24] Fortunately for Eretna, Hasan Kuchak was murdered by his own wife, who was afraid of the discovery of her extramarital affairs with Yaqub Shah, imprisoned by Hasan Kuchak for his alleged flaws at the Battle of Karanbük. This news helped Eretna even more as this prevented any retaliation for his earlier victory.[25]

Reign

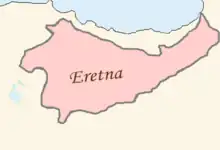

After the battle and Hasan Kuchak's death, Eretna took the title sultan and the name Alāʾ al-Dīn, dispersed coins in his name, and formally declared sovereignty as part of the khutbah. He additionally expanded his borders beyond Erzurum.[26] He faced a reduced number of threats to his rule in this period: Despite the intentions of the new Chobanid ruler Malek Ashraf to wage a war against him, such an expedition never came to be. The political vacuum in Mamluk Egypt, following Al-Nasir Muhammad's death, allowed Eretna to take Darende from them. And the Dulkadirid ruler Qarāja's focus in pillaging the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and tensions with the Mamluk emirs also made an attack from south unlikely.[27] Eretna further took advantage of the Karamanid ruler Ahmed's death in 1350, capturing Konya. Overall, Eretna's realm extended from Konya to Ankara and Erzurum,[28] also incorporating Kayseri, Amasya, Tokat, Çorum, Develi, Karahisar, Zile, Canik, Ürgüp, Niğde, Aksaray, Erzincan, Şebinkarahisar, and Darende when he died. Eretna passed away in February[29] or March 1352 and was buried in the kumbet located in the courtyard of Köşkmedrese in Kayseri.[30]

Eretna was a fluent Arabic-speaker according to Ibn Battuta[31] and was considered a scholar among the scholars of his era. He was famously known as Köse Peyghamber (lit. 'the beardless prophet') by his subjects who looked upon him favorably because his rule preserved order in a region that was politically crumbling apart.[3] He promoted and reinforced the sharia law in his domains and showed an effort to respect and sustain the ulama, sayyids, and sheikhs. An exception to the praise he received was al-Maqrizi's accusation that he allowed the state to later fall apart.[32]

Eretna benefited from the support of the significant population of Mongol tribes in Central Anatolia (referred to as Qarā Tātārs in sources) in asserting his rule. He thus highlighted his succession to the Mongol tradition despite his Uyghur origin.[33] When he stopped referring to an overlord after 1341–2 and issued his own coins, he utilized the Uyghur script, which was also used for Mongolian,[1] to underline the Mongol heritage he sought to represent.[34] Eretna's identification with the Mongol tradition and repudiation of Mamluk sovereignty is in parallel with the overall character of medieval Anatolian rulers, who often experimented with various methods of claiming legitimacy in an atmosphere in which long-standing concepts of legitimacy were ceasing to exist.[31] Still, instead of the Mongols, who were numerous in the region from Kütahya to Sivas, Eretna appointed mamluks and local Turks in administrative positions fearing the rebirth of the Mongol rule.[35] Eretna was still not totally successful in the long run, as his descendants would be evicted from the throne by Kadi Burhan al-Din, who highlighted his maternal Seljuk descent but also depended on the military support of some of the Mongol tribes.[31]

Despite the existence of some texts that described his character and skills, there is a scant number of literary works that were dedicated to his and his descendants' rule. One such text was a short Persian tafsir in al-As'ila wa'l-Ajwiba by Aqsara'i commissioned by the Eretnid emir of Amasya, Sayf al-Din Shadgeldi (died 1381). Another instance was an astrological almanac (taqwīm) created for the last Eretnid ruler ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Ali in 1371–2.[31] There are also no mosques, madrasas, caravanserais, hospitals, or bridges dated back to Eretna's rule.[36]

Family

Eretna's wives included Togha Khatun[lower-alpha 3] and Isfahan Shah Khatun.[30] He was known to have had three sons: Hasan, Muhammad, and Jafar. Sheikh Hasan was the governor of Sivas[30] and died in December 1347[30] or January 1348[29] due to sickness shortly after he was married to an Artuqid princess.[29]

Notes

- The year he declared independence is sometimes interpreted as 1341.

- Also spelled Eretne, Artanā, Ärätnä, or Ärdäni.

- Ibn Battuta wrote about having met her in Kayseri.[30]

References

- Peacock 2019, p. 182.

- Spuler & Ettinghausen 2012.

- Cahen 2012.

- Bosworth 1996, p. 234; Masters & Ágoston 2010, p. 41; Nicolle 2008, p. 48; Cahen 2012; Sümer 1969, p. 22; Peacock 2019, p. 51.

- Sümer 1969, p. 22.

- Bosworth 1996, p. 234; Nicolle 2008, p. 48; Cahen 2012.

- Nicolle 2008, p. 48.

- Sümer 1969, p. 84.

- Sümer 1969, p. 85.

- Sümer 1969, p. 23.

- Sümer 1969, p. 93.

- Peacock 2019, p. 50.

- Melville 2009, p. 91.

- Peacock 2019, p. 92.

- Melville 2009, p. 92.

- Sümer 1969, p. 92.

- Sümer 1969, p. 101.

- Melville 2009, p. 94.

- Melville 2009, p. 94–95.

- Melville 2009, p. 95.

- Sinclair 2019, p. 89.

- Sümer 1969, p. 104.

- Sümer 1969, p. 105.

- Sinclair 1989, p. 286.

- Sümer 1969, p. 104–105.

- Sümer 1969, p. 110.

- Sümer 1969, p. 111.

- Sümer 1969, p. 113.

- Sümer 1969, p. 121.

- Göde 1995.

- Peacock 2019, p. 62.

- Melville 2009, p. 96.

- Peacock 2019, p. 51.

- Peacock 2019, p. 61.

- Sümer 1969, p. 115.

- Sümer 1969, p. 114.

Bibliography

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1996). New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press.

- Cahen, Claude (2012). "Eretna". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. II. E. J. Brill.

- Göde, Kemal (1995). "Eretnaoğulları". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. TDV İslâm Araştırmaları Merkezi. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- Masters, Bruce Alan; Ágoston, Gábor (2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase.

- Melville, Charles (12 March 2009). "Anatolia under the Mongols". In Fleet, Kate (ed.). The Cambridge History of Turkey (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–101. doi:10.1017/chol9780521620932.004. ISBN 978-1-139-05596-3. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- Nicolle, David (2008). The Ottomans: Empire of Faith. Thalamus. ISBN 978-1-902886-11-4.

- Peacock, Andrew Charles Spencer (17 October 2019). Islam, Literature and Society in Mongol Anatolia. Cambridge University Press.

- Sinclair, T. A. (31 December 1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume II. Pindar Press. ISBN 978-0-907132-33-2.

- Sinclair, Thomas (6 December 2019). Eastern Trade and the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages: Pegolotti’s Ayas-Tabriz Itinerary and Its Commercial Context. Taylor & Francis.

- Spuler, Bertold; Ettinghausen, Richard (2012). "Īlk̲h̲āns". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. II. E. J. Brill.

- Sümer, Faruk (1969). "Anadolu'da Moğollar" [Mongols in Anatolia] (PDF). Journal of Seljuk studies (in Turkish). Ankara: Selçuklu Tarih ve Medeniyeti Enstitüsü (published 1970). Retrieved 19 October 2023.