Zayn al-Din Qaraja

Zayn al-Dīn Qarāja Beg (Turkish: Zeyneddin Karaca Bey; c. 1279[lower-alpha 1] – 11 December 1353) was a Turkoman chieftain who founded the Dulkadirid principality in southern Anatolia and northern Syria, ruling from 1337 to 1353. Before his ascendance, Qarāja competed with Ṭaraqlu, another local Turkoman warlord, over the administration of the northern frontier of the Mamluks. After gaining recognition from the Mamluk Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad, he became the head of a client state on their Anatolian extremity. During his rule, Qarāja grew more ambitious and clashed with various Mamluk governors who were against his expanding influence. Qarāja took advantage of the political turmoil within the Mamluks and declared independence in 1348. However, this led to his imprisonment and subsequent execution in 1353.

| Qarāja Beg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beg of Dulkadir | |||||

| Reign | 1337–1353 | ||||

| Coronation | 1337 | ||||

| Predecessor | Position established | ||||

| Successor | Ghars al-Dīn Khalīl | ||||

| Born | c. 1279[lower-alpha 1] | ||||

| Died | 11 December 1353 Cairo, Mamluk Sultanate | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Dulkadir | ||||

| Father | Dulkadir | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Early life and background

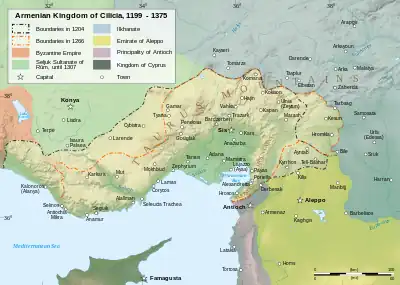

During the thirteenth century, the region around Marash in southern Anatolia was ruled by the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. The region came under the dominion of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt in 1298. Qarāja was one of the Turkoman lords, or begs, dwelling there who were granted the right to administer part of the region by the Mamluks. Qarāja founded the Dulkadirid principality around the same time the Eretnids emerged in central and eastern Anatolia, which was a breakaway state from the Ilkhanids led by the Turco-Mongol officer Eretna.[4]

Qarāja likely belonged to the Bayat tribe.[5] He became the leader of the Bozok tribal confederation in northern Syria after his father died in 1310 or 1311.[5] The first mention of him in sources is thought to be from 1317, when the Mamluk Sultan Al-Nasir Muhammad granted a Turkoman lord residing in Birga[lower-alpha 2] the title emir.[6]

Rise to power

Another local ruler, Ṭaraqlu Khalīl bin Tarafī, had earlier captured Elbistan from the Eretnids. In order to expand his authority over the region by pledging allegiance to the Mamluks, Ṭaraqlu sent a gift of 100 horses to the emir of Aleppo, Altunbogha, and visited the sultan in Cairo. As a response to this threat to his political presence, Qarāja sent his son Khalīl to lead an offensive against Ṭaraqlu.[7] Elbistan was captured by the Dulkadirids in 1335[8] or 1337.[9] Ṭaraqlu's ally, Altunbogha, threatened Qarāja and demanded that he come to Aleppo. Instead, Qarāja allied himself with Tankiz, the governor of Damascus and rival of Altunbogha. Meanwhile, Qarāja faced another threat; Tashgun, another local emir backed by Altunbogha, started raiding and harassing the Dulkadirids, though Tashgun was eventually caught with the intervention of Tankiz.[10]

The Sultan finally summoned the governors, Ṭaraqlu, and Qarāja. Tankiz defended Qarāja and recommended to the sultan that Qarāja would be better able to maintain Mamluk authority over the region, insisting that Ṭaraqlu possessed no more than a thousand horsemen.[4] Al-Nasir Muhammad thus recognized Qarāja as the Emir of the Turkomans[9] and the na'ib of the lands stretching from Marash to Elbistan in 1337.[11][12] The next year, Qarāja also captured Harpoot, Darende, Gemerek, and Gürün from the Eretnids.[13][8]

Downfall and execution

Qarāja's ambition to become an independent ruler manifested after al-Nasir Muhammad's death in 1341 and the consequent unrest in Egypt. He tried to gain Eretna's trust in order to organize a joint campaign to take over Aleppo. Emir Tashtimur of Aleppo requested assistance from Egypt, but this proved to be futile as Cairo was facing internal power struggles. The prominent Mamluk emir Qawsun overthrew Al-Mansur Abu Bakr and installed Abu Bakr's seven-year-old brother Al-Ashraf Kujuk on the Mamluk throne. This led to Tashtimur's rebellion, who now found his situation reversed as he was pursued by the Mamluks and escaped to Eretna in the north with the protection of Qarāja. When An-Nasir Ahmad briefly came to power amidst the political vacuum and invited Tashtimur, who supported him, to Cairo for a new appointment, Qarāja escorted him there. But Tashtimur was instead jailed and executed for unknown reasons, while Qarāja swiftly returned north.[14]

Qarāja's relations with the Mamluks further deteriorated in 1343, when the Dulkadir Turkomans robbed a caravan containing Eretna's gifts to the Mamluk emir Yalbugha, though Qarāja was able to get a pardon from the sultan.[13] He led several incursions into the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, looting the region and occupying Androun and Kapan in 1345.[15][16] In 1348, gaining confidence from his victories,[16] he declared independence as Malik al-Qāhir.[17] Qarāja further joined emir Baybugha's revolt against the Mamluk state[18] and defeated Yalbugha.[17] In response, Mamluk governors of Syria and rival Turkoman tribal leaders joined forces, supposedly raising 10 to 25 thousand troops. They ransacked Elbistan as well as the nearby villages, while Qarāja fled to Mount Düldül. Two of his sons, including his successor Ghars al-Dīn Khalīl Beg, tried to fend off the Mamluk forces but were defeated and captured.[2]

In 1353, Qarāja took refuge in the court of the Eretnid ruler Giyath al-Din Muhammad,[8] but at the request of the Mamluks he was chained and sent to Aleppo on 22 September 1353, for which Muhammad was paid 500 thousand dinars. One of Qarāja's sons agreed with the Bedouin leader Jabbar bin Muhanna to attack Aleppo in order to save his father. This was unsuccessful and further angered Sultan Salih, who demanded Qarāja's transfer to Cairo. Sultan Salih scolded him in person and kept him in the Citadel of Cairo. After being imprisoned for 48 days, he was tortured to death on 11 December 1353. His corpse was left hanging in Bab Zuweila for 3 days.[17]

Although disproven by medieval Arab historians, late Ottoman sources, such as Halil Edhem and Ahmed Arifi Pasha, popularly believed that Qarāja continued to resist the Mamluks until he died of old age at around 100 in 1378 or 1379.[19]

Family

Qarāja had 6 sons: Khalīl, Ibrāhīm, Isā, Sūlī, 'Usmān, and Davud.[4] Ghars al-Dīn Khalīl succeeded Qarāja as the second ruler of the Dulkadirids. Sūlī was the third ruler of the Dulkadirids. Ṣārim al-Dīn Ibrahim became the lord of Harpoot[4][20] and was appointed by the Mamluks as amīr ṭablkhāna (lit. 'amir of the band') of Damascus as a gesture of goodwill to keep his father, Qarāja, as an ally.[4] Qarāja is known to have had a brother and cousin, both of whom were given land by the Mamluk sultan in 1344 or 1345.[21]

See also

- al-Maqrizi, one of the medieval historians who wrote about Zayn al-Dīn

- Ramadanids, neighboring Turkoman principality

Notes

- Based on the erroneous belief by the Ottoman writers Halil Edhem and Ahmed Arifi Pasha that he died 100 years old in 1378–9.

- historically also known as Bile, Birtha, and Birah, and in modern times as Birecik

References

- Bosworth 1996, pp. 238.

- Alıç 2020, pp. 85.

- Kaya 2014, pp. 83.

- Venzke 2017.

- Alıç 2020, pp. 84.

- Yinanç 1988, pp. 9.

- Kaya 2014, pp. 86–88.

- Sinclair 1987, pp. 518.

- Kaya 2014, pp. 88.

- Yinanç 1988, pp. 11–12.

- Oberling 1996, pp. 573–574.

- Har-El 1995, pp. 40.

- Kaya 2014, pp. 87.

- Yinanç 1988, pp. 12–13.

- Toursarkisian 1897, pp. 29–30.

- Merçil 1991, pp. 291.

- Alıç 2020, pp. 85–86.

- Merçil 1991, pp. 313.

- Alıç 2020, pp. 86.

- von Zambaur 1927, pp. 159.

- Venzke 2000, pp. 412.

Bibliography

- Alıç, Samet (2020). "Memlûkler Tarafından Katledilen Dulkadir Emirleri" [The Dulkadir's Emirs Killed by the Mamluks]. The Journal of Selcuk University Social Sciences Institute (in Turkish) (43): 83–94. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1996). New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press.

- Har-El, Shai (1995). Struggle for Domination in the Middle East: The Ottoman-Mamluk War, 1485-91. E.J. Brill. ISBN 9004101802. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Kaya, Abdullah (2014). "Dulkadirli Beyliği'nin Eratnalılar ile Münasebetleri" [Relations between Dulkadirli Beylik and the Eretnids]. Mustafa Kemal University Journal of Graduate School of Social Sciences (in Turkish). 11 (25): 81–97. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- Merçil, Erdoğan (1991). Müslüman-Türk devletleri tarihi [A history of Muslim-Turkish states] (in Turkish). Turkish Historical Society Press.

- Oberling, Pierre (1996). "Ḏu'l-Qadr". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. VII, Fasc. 6. pp. 573–574.

- Sinclair, Thomas Alan (1987). Eastern Turkey An Architectural and Archaeological Survey. Vol. II. Pindar Press.

- Toursarkisian, Garabed (1897). "Histoire de Zeïtoun" [A history of Zeytun (now Süleymanlı)]. Mercure de France (in French): 25–175. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- Venzke, Margaret L. (2000). "The Case of a Dulgadir-Mamluk Iqṭāʿ: A Re-Assessment of the Dulgadir Principality and Its Position within the Ottoman-Mamluk Rivalry". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 43 (3): 399–474. doi:10.1163/156852000511349. JSTOR 3632448. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Venzke, Margaret L. (2017). "Dulkadir". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Stewart, Denis J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. III. E. J. Brill.

- von Zambaur, Eduard Karl Max (1927). Manuel de généalogie et de chronologie pour l'histoire de l'Islam avec 20 tableaux généalogiques hors texte et 5 cartes [Handbook of genealogy and chronology for the history of Islam: with 20 additional genealogical tables and 5 maps] (in French). H. Lafaire. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- Yinanç, Refet (1988). Dulkadir Beyliği (in Turkish). Ankara: Turkish Historical Society Press.