Ethnic groups in Cambodia

The largest of the ethnic groups in Cambodia are the Khmer, who comprise approximately 90% of the total population and primarily inhabit the lowland Mekong subregion and the central plains. The Khmer historically have lived near the lower Mekong River in a contiguous arc that runs from the southern Khorat Plateau where modern-day Thailand, Laos and Cambodia meet in the northeast, stretching southwest through the lands surrounding Tonle Sap lake to the Cardamom Mountains, then continues back southeast to the mouth of the Mekong River in southeastern Vietnam.

Ethnic groups in Cambodia other than the politically and socially dominant Khmer are classified as either "indigenous ethnic minorities" or "non-indigenous ethnic minorities". The indigenous ethnic minorities, more commonly collectively referred to as the Khmer Loeu ("upland Khmer"), constitute the majority in the remote mountainous provinces of Ratanakiri, Mondulkiri and Stung Treng and are present in substantial numbers in Kratie Province.

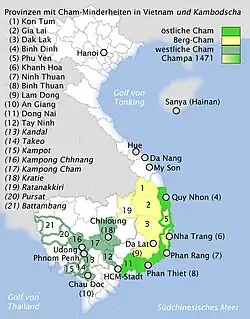

Approximately 17-21 separate ethnic groups, most of whom speak Austroasiatic languages related to Khmer, are included in the Khmer Loeu designation, including the Kuy and Tampuan people. These peoples are considered to be the aboriginal inhabitants of the land by the Cambodian authorities. Two of these highland groups, the Rade and the Jarai, are Chamic peoples who speak Austronesian languages descended from ancient Cham. These indigenous ethnic minorities haven't integrated into Khmer culture and follow their traditional animist beliefs.

The non-indigenous ethnic minorities include immigrants and their descendants who live among the Khmer and have adopted, at least nominally, Khmer culture and language. The three groups most often included are the Chinese Cambodians, Vietnamese and Cham peoples. The Chinese have immigrated to Cambodia from different regions of China throughout Cambodia's history, integrating into Cambodian society and today Chinese Cambodians or Cambodians of mixed Sino-Khmer ancestry dominate the business community, politics and the media. The Cham are descendants of refugees from the various wars of the historical kingdom of Champa. The Cham live amongst the Khmer in the central plains but in contrast to the Khmer who are Theravada Buddhists, the vast majority of Cham follow Islam.[1]

There are also small numbers of other minority groups. Tai peoples in Cambodia include the Lao along the Mekong at the northeast border, Thai (urban and rural), and the culturally Burmese Kola, who have visibly influenced the culture of Pailin Province. Even smaller numbers of recent Hmong immigrants reside along the Lao border and various Burmese peoples have immigrated to the capital, Phnom Penh.

Ethnic Khmer

The Khmers are one of the oldest ethnic groups in the area, having filtered into Southeast Asia around the same time as the Mon. Most archaeologists and linguists, and other specialists like Sinologists and crop experts, believe they arrived no later than 2000 BCE (over four thousand years ago) bringing with them the practice of agriculture and in particular the cultivation of rice. They were the builders of the later Khmer Empire which dominated Southeast Asia for six centuries beginning in 802 CE, and now form the mainstream of political, cultural, and economic Cambodia.

The Khmers developed the first alphabet still in use in Southeast Asia which in turn gave birth to the later Thai and Lao scripts. The Khmers are considered by most archaeologists and ethnologists to be indigenous to the contiguous regions of Isan, southernmost Laos, Cambodia and Southern Vietnam. That is to say the Khmer have historically been a lowland people who lived close to one of the tributaries of the Mekong.

The Khmers see themselves as being one ethnicity connected through language, history and culture, but divided into three main subgroups based on national origin. The Khmer of Cambodia speak a dialect of the Khmer language. The Northern Khmer (Khmer Surin) are ethnic indigenous Khmers whose lands once belonged to the Khmer Empire but have since become part of Thailand. The Northern Khmer also speak the Isan language fluently.

Maintaining close relations with the Khmer of Cambodia, some now reside in Cambodia as a result of marriage. Similarly, the Khmer Krom are indigenous Khmers living in the regions of the former Khmer Empire that are now part of Vietnam. Fluent in both their particular dialect of Khmer and in Vietnamese, many have fled to Cambodia as a result of persecution and forced assimilation by Vietnam.

All three varieties of Khmer are mutually intelligible. While the Khmer language of Cambodia proper is non-tonal, surrounding languages such as Thai, Vietnamese and Lao are all highly tonal and have thus affected the dialects of Northern Khmer and Khmer Krom.

Vietnamese

Prior to the Cambodian Civil War, the Vietnamese were the most populous ethnic minority in Cambodia, with an estimated 450,000 living in provinces concentrated in the southeast of the country adjacent to the Mekong Delta. Vietnamese Cambodians also lived further upstream along the shores of the Tonlé Sap. During the war, the Vietnamese community in Cambodia was "entirely eradicated".[2] As of the 2013 Cambodian Inter-Censal Population Survey, speakers of Vietnamese accounted for 0.42%, or 61,000, of Cambodia's 14.7 million people.[3]

Most of these came to the country as a result of the post-civil war Vietnamese invasion and occupation of Cambodia, during which time the Vietnamese-installed government of Cambodia (the People's Republic of Kampuchea) relied heavily on Vietnam for the rebuilding of its economy. Following the 1993 withdrawal of Vietnamese troops, the government of modern Cambodia maintained close ties with Vietnam and Vietnamese-backed ventures came to the country looking to capitalize on the new market. In addition to these mostly urban immigrants, some villagers cross the border illegally, fleeing impoverished rural conditions in Vietnam's socialist one-party state hoping for better opportunities in Cambodia.

Although the Vietic languages are also within the Austroasiatic language family like Khmer, there are very few cultural connections between the Vietnamese peoples because the early Khmers were part of Greater India while the Vietnamese are part of the East Asian cultural sphere and adopted Chinese literary culture.[4]

Ethnic tensions between the two can be traced to the Post-Angkor Period (from the 16th to 19th centuries), during which time a nascent Vietnam and Thailand each attempted to vassalize a weakened post-Angkor Cambodia, and effectively dominate all of Indochina. Control over Cambodia during this, its weakest point, fluctuated between Thailand and Vietnam. Vietnam unlike Thailand, wanted Cambodia to adopt Vietnamese governmental practices, dress, and language. The Khmers resented and resisted until they were incorporated into the colonial French Indochina.

During the colonial period, the French brought over Vietnamese middlemen to administer the local Cambodian government, causing further resentment and anti-Vietnamese sentiment that endures to the present.[4]

Due to the long history of the two countries, there is a significant amount of Cambodians of mixed Vietnamese and Khmer ancestry. Most of these Vietnamese-Cambodians no longer speak Vietnamese and have assimilated into Khmer society and identify as Khmer. They have engaged primarily in aquaculture in the Mekong Delta of the southeast.

Chinese

Chinese Cambodians are approximately 1% of the population.[5][6] Most Chinese are descended from 19th–20th century settlers who came in search of trade and commerce opportunities during the time of the French protectorate. Waves of Chinese migration have been recorded as early as the twelfth century during the time of the Khmer Empire. Most are urban dwellers, engaged primarily in commerce.

The Chinese in Cambodia belong to five major linguistic groups, the largest of which is the Teochiu accounting for about 60%, followed by the Cantonese (20%), the Hokkien (7%), and the Hakka and the Hainanese (4% each).

Intermarriage between the Chinese and Khmers has been common, in which case they would often assimilate into mainstream Khmer society, retaining few Chinese customs. Much of the Chinese population dwindled under Pol Pot during the Cambodian Civil War. The Chinese were not specifically targets for extermination, but suffered the same brutal treatment faced by the ethnic Khmers during the period.

Tai

Tai peoples present in Cambodia include the Thai, Lao, Tai Phuan, Nyaw, Shan, and the Kula (Khmer: កុឡា, Kŏla, also known by the Thai designation, "Kula", and, historically, by the Burmese name, "Tongsoo"). Thai speakers in Cambodia amount to less than .01% of the population.[3] The ethnic Thai population numbered in the tens of thousands before the Cambodian Civil War but in 1975 over five thousand fled across the border into Thailand while another 35 thousand were systematically evacuated from Koh Kong Province and many were killed as spies.[7]

In modern times, Thai people are mainly to be found in the capital, Phnom Penh, primarily as families of either the diplomatic mission or representatives of Thai companies doing business in Cambodia. The northwestern provinces were administratively a part of Thailand for most of the period from the 1431 fall of Angkor until the 20th century French Protectorate. Descendants of the Thais and many people of Khmer-Thai ancestry reside in these provinces, but have mostly assimilated to Khmer culture and language and are indistinguishable from their fellow Khmer villagers.

Lao

Lao people reside in the far northeast of the country, inhabiting villages scattered among the hill tribes and along the Mekong and its tributaries in the mountainous regions near the Lao border. Historically part of Funan and later the heartland of the pre-Angkorian Khmer Chenla Kingdom, the region now encompassed by Stung Treng, Ratanakiri and parts of Preah Vihear, Kratie and Mondulkiri Provinces were all but abandoned by the Khmer during the Middle Period as the Khmer Empire waned and the population moved south to more strategic and defensible positions.[8]

The area fell under the rule of the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang in the 14th century and remained part of successive Lao kingdoms until, in 1904 during the French Indochina period, the region was returned to Cambodian administration. Consequently, notwithstanding the relatively recent immigration of Khmers back to the area, as of 2010, ethnic Lao constituted more than half the population of Stung Treng, a substantial number (up to 10%) in Ratanakiri and smaller communities in Preah Vihear and Mondulkiri.[8]

Lao speakers make up .17% of Cambodia's population,[3] but many Cambodians of Lao ancestry are becoming increasingly Khmerized. Lao born in Cambodia are considered Khmer according to government policy. The Cambodian Lao have little to no political organization or representation, leaving many hesitant to identify as Lao due to fears related to historical persecution.[8]

Kola

Little is known about the precise origins of the Kola people[9] who, prior to the Civil War, constituted a significant minority in Pailin Province, where they have visibly influenced the local culture.[10] They kept very few written records of their own, but they appear to have originated as an amalgamation of Shan and Dai (specifically, Tai Lue and Tai Nua) traders who began migrating south from the eastern Burma-China border in the 1800s.

As they journeyed through Burma and Northern Thailand during this turbulent period, they were joined by individuals from the Mon, Pa'O and various other Burmese groups, primarily from Moulmein. The Kola sojourned in Isan (Northeast Thailand) seeking more favorable trading conditions until the 1856 Bowring Treaty guaranteed their rights as British subjects (having originated in what became British Burma) in Thailand. By the late 1800s, the Kola were settling in the mountains of Chanthaburi Province and neighboring Pailin, which was then still governed by Thailand, working as miners.[11]

The success of the Kola in Pailin encouraged further immigration of Shan directly from Burma who then joined the Kola community. The Kola language, which is a Creole based on Shan and Dai and includes words from Lanna, Burmese and Karen, has influenced the local Khmer dialect in Pailin in both tone and pronunciation. Their Burmese influence can also be seen in the local style of dress, including the umbrellas women carry, as well as the local cuisine and Burmese style pagodas.[11]

The Kola in Pailin were historically active in the lucrative gem trading business and were the most prosperous ethnic group in the region before the war. As the Khmer Rouge, whose official policy was to persecute all non-Khmer ethnic groups, took control of Pailin, the Kola fled across the border into Thailand.[10] Since the breakup and surrender of the Khmer Rouge in the 1990s, many Kola have returned to Pailin, although preferring to keep a lower profile, most no longer outwardly identify as Kola.[11]

Phuan

In the northwest of the country, approximately 5000 Tai Phuan live in their own villages in Mongkol Borey District of Banteay Meanchey Province.[12] The Phuan in Cambodia are the descendants of captives sent to Battambang as laborers by Siam during the reign of Rama III (1824-1851) when Siam ruled most of Laos and Cambodia. As of 2012 they resided in ten villages and still spoke the Phuan language, a language closely related to Lao and Thai. The dialect of the Phuan people in Cambodia most closely resembles the Phuan spoken in Thailand.[13]

Nyo

Approximately 10,000 Lao Nyo, also known as Yor, also live in Banteay Meanchey Province. Although they refer to themselves as "Nyo" (pronounced /ɲɑː/), they speak a dialect of the Lao language and are distinct from the Nyaw people of Northern Isan and Laos.[14] Their villages are concentrated in Ou Chrov District near the border with Thailand. They are so numerous in the province that many ethnic Khmer are able to speak some Nyo. The presence of the Nyo and the peculiarities of their language in western Cambodia is considered anomalous and has not yet been explained by scholars.[12]

Cham

The Cham are descendants of a sea-faring Austronesian people from the islands of Southeast Asia who, 2000 years ago, began settling along the central coast of present-day Vietnam and, by 200 AD, had begun building the various polities that would become the kingdom of Champa,[15] which at its zenith from the eighth to tenth centuries controlled most of what is today the south of Vietnam and exerted influence as far north as present-day Laos.

Primarily a coastal, maritime kingdom, Champa was a contemporary and rival of the Khmer Empire of Angkor. During the ninth through 15th centuries, the relationship between Champa and the Khmer ranged from that of allies to enemies. During friendly periods there was close contact and trade between the two Indianized kingdoms and intermarriage between the respective royal families. During wartime, many Chams were brought into Khmer lands as captives and slaves. Champa was conquered by Dai Viet (Vietnam) in the late 15th century and much of its territory was annexed while thousands of Cham were enslaved or executed.[16]

This resulted in mass migrations of Chams. The Cham king fled to Cambodia with thousands of his people while others escaped by boat to Hainan (Utsuls) and Aceh (Acehnese people). These migrations continued for the next 400 years as the Vietnamese slowly chipped away at the remains of Champa until the last vestige of the kingdom was annexed by Vietnam in the late 19th century.

The Cham in Cambodia number approximately a quarter of a million and often maintain separate villages although in many areas they live alongside ethnic Khmers. Cham have historically been concentrated in the southeast of the country where they've lent their name to Kampong Cham Province which, prior to a provincial restructuring in 2013, extended to the Vietnamese border and was the second most populated province in Cambodia.

Primarily fishermen or farmers, the Cham are believed by many Khmer to be especially adept at certain spiritual practices and will sometimes be sought out for healing or tattooing. Cham people in Cambodia maintain a distinctive dress and speak the Western Cham language which, due to centuries of divergence, is no longer mutually intelligible with the Eastern Cham language spoken by Cham in neighboring Vietnam. Cambodian Cham was historically written in the Indic-based Cham alphabet, but it is no longer in use, having been replaced by an Arabic-based script.

While the Cham in Vietnam still follow traditional Shivaite Hinduism, most (an estimated 90%) Cham in Cambodia are ostensibly followers of Sunni Islam. Interaction between those who are Muslim and those who are Hindu is often taboo. Intermarriage between Khmers and Chams has taken place for hundreds of years. Some have assimilated into mainstream Khmer society and practice Buddhism. The Cham were one of the ethnic groups marked as targets of persecution under the Khmer Rouge rule of Cambodia. Their very existence was declared to be illegal.[17] Cham villages were destroyed and the people were either forced to assimilate or summarily executed. Estimates of Chams killed from 1975 to 1979 range as high as 90,000, including 92 of the country's 113 imams.[2][18]

Since the end of the war and the ouster of the Khmer Rouge, Hun Sen's government has made overtures to the Cham people and now many Cham serve in government or other official positions. However, in spite of the moderate Malay form of Islam traditionally practiced by the Cham, the Cham community has recently turned to the Middle East for funding to build mosques and religious schools, which has brought imams from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait teaching fundamentalist interpretations including Da'Wah Tabligh and Wahhabism.[18] These newly introduced forms of Islam have also influenced Cham dress; Many Cham are forgoing their traditional formal attire in favor of more Middle Eastern or South Asian dress.

Khmer Loeu

The indigenous ethnic groups of the mountains are known collectively as Montagnards or Khmer Loeu, a term meaning "Highland Khmer". They are descended from neolithic migrations of Mon–Khmer speakers via southern China and Austronesian speakers from insular Southeast Asia. Being isolated in the highlands, the various Khmer Loeu groups were not Indianized like their Khmer cousins and consequently are culturally distant from modern Khmers and often from each other, observing many pre-Indian-contact customs and beliefs. Most are matrileneal, tracing ancestry through maternal rather than paternal bloodlines. They grow rice and live in tribal villages.

Historically, as the Khmer Empire advanced, they were obliged to seek safety and independence in the highlands or become slaves and laborers for the empire. Zhou Daguan remarked that the Khmers had captured hill tribes and made them laborers referring to them as the Tchouang or slave caste. Tchouang, from the Pear word juang, means people. Presently, they form the majority in the sparsely populated provinces of Ratanakiri, Stung Treng, and Mondulkiri.

Their languages belong to two groups, Mon–Khmer and Austronesian. The Mon–Khmers are Pear, Phnong, Stieng, Kuy, Kreung, and Tampuan. The Austronesians are Rhade and Jarai. Once thought to be a mixed group, the Austronesians have been heavily influenced by the Mon–Khmer tribes.

French Colons and Post-Conflict Arrivals

Prior to the Cambodian Civil War which lasted from between 1970 until the Khmer Rouge victory on April 17, 1975, there were an estimated 30,000 colons, or French citizens living in the country. After the civil war began most left to go back to France or to live in the United States. Cambodia was ruled by the French for nearly a century until independence in 1953 and French language and culture still retains a prestigious position amongst the Khmer elite.

After the Khmer Rouge were defeated by the Vietnamese in 1979, they retreated back towards the Thai border in the west of the country by expelling Vietnamese forces, Vietnam then occupied Cambodia for the next ten years. During this time Cambodia was isolated from the Western world, however visitors from states with ties to the Soviet bloc trickled into the country in (albeit) small numbers.

In post-conflict Cambodia today, many other ethnic groups can be found, particularly in Phnom Penh, in statistically significant numbers. After the United Nations helped restore the monarchy in the early 1990s, the number of Western individuals (termed barang by the Khmer) living in the country swelled into the tens of thousands. And due to the further economic boom of the 21st century (Cambodia's economic growth has averaged over 7% in the decade after 2001), these numbers have only risen.

Expatriate workers from across the globe probably number around 150,000 in the capital of Phnom Penh alone. These diplomats, investors, archaeologists, lawyers, artists, entrepreneurs, and NGO employees include sizeable numbers of Europeans, Americans and Australians, as well as those from neighbouring Southeast Asian states, Koreans, Japanese, Chinese and Russians, along with smaller numbers of Africans.

Ethnic groups

| Ethnic group | Population | % of total* |

|---|---|---|

| Khmer | 13,684,985 | 90% |

| Vietnamese | 800,000 | 5% |

| Chinese | 152,055 | 1% |

| Other | 608,222 | 4% |

- Cham – Descendants of Cham refugees who fled to Cambodia after the fall of Champa. 222,808 (2012 est.)

- Chinese – Descendants of Chinese settlers in Cambodia. 695,852 (2012 est.)

- Khmer

- Khmer Kandal – "Central Khmers" Ethnic Khmers indigenous to Cambodia proper.

- Khmer Krom – "Lowland Khmers" Ethnic Khmers indigenous to Southeastern Cambodia and the adjoining Mekong Delta region of Southern Vietnam. The provinces of South Vietnam all bear ancient Khmer names as they were once part of the Khmer Empire, until the 19th century when the French made Cambodia a protectorate.

- Khmer Surin – "Surin Khmers" Ethnic Khmer indigenous to Northwestern Cambodia and adjacent areas in Surin, Buriram and Sisaket provinces in Northeast Thailand, in the region known as Isan. These provinces were formerly part of the Khmer Empire but were annexed by Thailand in the 18th century.

- Khmer Loeu – "Highland Khmers" Umbrella term used to designate all hill tribes in Cambodia, irrespective of their language family.

- Mon–Khmer speakers

- Kachok

- Krung – There are three distinct dialects of Krung. All are mutually intelligible.

- Krung

- Brao

- Kavet

- Kraol - 2,000 (est.)

- Mel- 3,100 (est.)

- Kuy – A small group of people mostly located in the highlands of Cambodia.

- Phnong or Mnong, ethnic group located on the eastern province of Mondulkiri.

- Tampuan – Ethnic group located in the Northeastern province of Ratanakiri.

- Stieng – Often confused with ethnic Degar (Montagnard)

- Samre

- Chong

- Sa'och

- Somray

- Suoy

- Austronesian speakers

- Jarai – Mostly located in Vietnam, the Jarai extend into Cambodia's Ratanakiri Province.

- Rhade – The majority of Rhade, or Ê Đê, are located in Vietnam. They share close cultural ties with the Jarai and other tribes.

- Mon–Khmer speakers

- Tai

- Thai - 43,000 (est.)

- Lao - Living mainly in the Ratanakiri Province.

- Shan

- Kula

- Thai - 43,000 (est.)

- Vietnamese – Live mostly in Phnom Penh where they form a considerable minority and parts of southeastern Cambodia next to the Vietnamese border.

- Hmong–Mien - The Miao and Hmong are hill tribes that live in urban and rural areas.

- Tibeto-Burman

- Burmese - 4,700 (est.)

- Japanese - mainly first generation entrepreneurs and investors in Phnom Penh

- Koreans - mainly first generation entrepreneurs and investors in Phnom Penh

See also

References

- "Cambodia Ethnic Groups". Cambodia-travel.com. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- Kiernan, Ben (2012). "9. The Cambodian Genocide, 1975-1979". In Totten, Samuel; Parsons, William S (eds.). Centuries of Genocide: Essays and Eyewitness Accounts (4th ed.). Routledge. pp. 323–325. ISBN 978-1135245504. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Cambodia Inter-Censal Population Survey 2013 Final Report" (PDF). United Nation Population Fund, United Nation Cooperation Agency. National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Planning, Phnom Penh, Cambodia. November 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- David Chandler (2000). A History of Cambodia. Westview Press.

- "Ethnic groups statistics - countries compared". Nationmaster. Retrieved 2012-09-02.

- "Birth Rate". CIA – The World Factbook. Cia.gov. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Kiernan, Ben (May 2014). The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power, and Genocide in Cambodia Under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79 (Third ed.). New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 300. ISBN 978-0300142990. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- Baird, Ian (May 2010). "Different View of History: Shades of Irredentism along the Laos-Cambodia Border". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 41 (2): 187–213. doi:10.1017/S0022463410000020. S2CID 154683966.

- Koizumi, Junko (September 1990). "Why the Kula Wept: A Report on the Trade Activities of the Kula in Isan at the End of the 19th Century". Southeast Asian Studies. 28 (2).

- Aung, Shin; May, Sandy (12 March 2012). "Expat businessman restores remote pagoda in Cambodia". Myanmar Times. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Lewis, Simon; Phorn, Bopha (9 January 2015). "Cambodia's Kola Trace Myanmar Roots". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Schliesinger, Joachim (8 October 2011). Ethnic Groups of Cambodia, Volume 3: Profile of the Austro-Thai-and Sinitic-Speaking Peoples. White Lotus Co Ltd. p. 10. ISBN 978-9744801791. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Thananan, Trongdee (2015). "Phuan in Banteay Meancheay Province, Cambodia: Resettlement under the Reign of King Rama III of Siam". The Journal of Lao Studies. Center for Lao Studies (Special Issue 2): 144–166. ISSN 2159-2152.

- Thananan, Trongdee (2014). "The Lao-speaking Nyo in Banteay Meanchey Province of Cambodia" (PDF). Research Findings in Southeast Asian Linguistics, A Festschrift in Honor of Professor Pranee Kullavanijaya. Manusya. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Press (Special Issue 20). Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Thurgood, Graham (2004). From Ancient Cham to Modern Dialects: Two Thousand Years of Language Contact and Change (Oceanic Linguistics Special Publication No. 28 ed.). Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0824821319.

- Ben Kiernan (2009). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-300-14425-3. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–314.

- Cain, Geoffrey (9 October 2008). "Cambodia's Muslims as geopolitical pawns". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

Further reading

- Center for Advanced Study (ed): Ethnic Groups in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: Center for Advanced Study, 2009. ISBN 978-99950-977-0-7.

- "Cambodia: State grants three groups ethnic status | Heritage". Indigenousportal.com. 2010-11-27. Retrieved 2012-09-02.