F2 (classification)

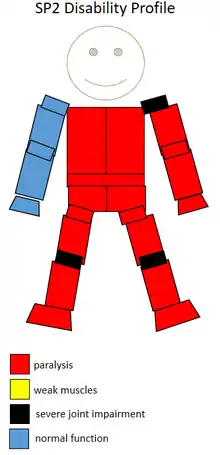

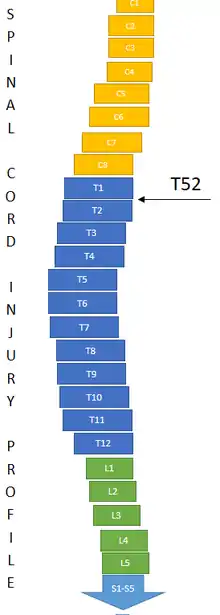

F2, also T2 and SP2, is a wheelchair sport classification that corresponds to the neurological level C7. Historically, it was known as 1B Complete, 1A Incomplete. People in this class are often tetraplegics. Their impairment effects the use of their hands and lower arm, and they can use a wheelchair using their own power.

The process for classification into this class has a medical and functional classification process. This process is often sport specific.

Definition

This is wheelchair sport classification that corresponds to the neurological level C7.[1][2] In the past, this class was known as 1B Complete, 1A Incomplete.[1][2]

In 2002, USA Track & Field defined this class as, " These athletes have limited or no hand function. Power for pushing now comes from elbow extension, wrist extension and active chest muscles. Their head may be forced backwards (by the use of neck muscles), producing slight upper trunk movements even though they do not have use of their trunk muscles. Neurological level: C7-C8."[3] Disabled Sports USA defined the functional definition of this class in 2003 as, "Have difficulty gripping with non-throwing arm. [...] These athletes may have slight function between the digits of the hand."[2]

Recommended sports for people at C7 include archery and table tennis.[4]

Neurological

Disabled Sports USA defined the neurological definition of this class in 2003 as C7.[2] People in this class are often tetraplegics level C7/C8 or higher incomplete lesion.[5]

Anatomical

The location of lesions on different vertebrae tend to be associated with disability levels and functionality issues. C7 is associated with elbow flexors. C8 is associated with finger flexors.[6] Disabled Sports USA defined the anatomical definition of this class in 2003 as, ""Have functional elbow flexors and extensors, wrist dorsi-flexors and palmar flexors. Have good shoulder muscle function. May have some finger flexion and extension but not functional."[2] People with lesions at C7 have stabilization and extension of the elbow and some extension of the wrist.[4]

Functional

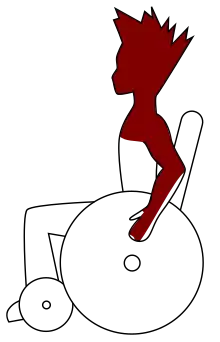

People with a lesion at C7 have an impairment that effects the use of their hands and lower arm.[7] They can use a wheelchair using their own power, and do everyday tasks like eating, dressing, and normal physical maintenance.[4] People in this class have a total respiratory capacity of 79% compared to people without a disability.[8]

People with spinal injuries at T6 or higher are more likely to develop Autonomic dysreflexia (AD). It also sometimes rarely effects people with injuries at T7 and T8. The condition causes over-activity of the autonomic nervous system, and can suddenly onset when people are playing sports. Some of the symptoms include nausea, high blood pressure, a pounding headache, flushed face, profuse sweating, a lower heart rate or a nasal congestion. If left untreated, it can cause a stroke. Players in some sports like wheelchair rugby are encouraged to be particularly on guard for AD symptoms.[9]

Governance

In general, classification for spinal cord injuries and wheelchair sport is overseen by International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation (IWAS),[10][11] having taken over this role following the 2005 merger of ISMWSF and ISOD.[12][13] From the 1950s to the early 2000s, wheelchair sport classification was handled International Stoke Mandeville Games Federation (ISMGF).[12][14][15]

Some sports have classification managed by other organizations. In the case of athletics, classification is handled by IPC Athletics.[16] Wheelchair rugby classification has been managed by the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation since 2010.[17] Lawn bowls is handled by International Bowls for the Disabled.[18] Wheelchair fencing is governed by IWAS Wheelchair Fencing (IWF).[19] The International Paralympic Committee manages classification for a number of spinal cord injury and wheelchair sports including alpine skiing, biathlon, cross country skiing, ice sledge hockey, powerlifting, shooting, swimming, and wheelchair dance.[11]

Some sports specifically for people with disabilities, like race running, have two governing bodies that work together to allow different types of disabilities to participate. Race running is governed by both the CPISRA and IWAS, with IWAS handling sportspeople with spinal cord related disabilities.[20]

Classification is also handled at the national level or at the national sport specific level. In the United States, this has been handled by Wheelchair Sports, USA (WSUSA) who managed wheelchair track, field, slalom, and long-distance events.[21] For wheelchair basketball in Canada, classification is handled by Wheelchair Basketball Canada.[22]

History

Early on in this classes history, the class had a different name and was based on medical classification and originally intended for athletics.[23][24][25] During the 1960s and 1970s, classification involved being examined in a supine position on an examination table, where multiple medical classifiers would often stand around the player, poke and prod their muscles with their hands and with pins. The system had no built in privacy safeguards and players being classified were not insured privacy during medical classification nor with their medical records.[26]

During the late 1960s, people oftentimes tried to cheat classification to get in classified more favorably. The group most likely to try to cheat at classification were wheelchair basketball players with complete spinal cord injuries located at the high thoracic transection of the spine.[27] Starting in the 1980s and going into the 1990s, this class began to be more defined around functional classification instead of a medical one.[15][28]

Sports

Athletics

Under the IPC Athletics classification system, this class competes in F52.[1][2] The class differs from T53 because T53 sportspeople have better trunk function and better function in their throwing arm.[29] Field events open to this class have included shot put, discus and javelin.[1][2] In pentathlon events in the United States, the events for this class have included Shot, Javelin, 100m, Discus, 800m.[2] They throw from a seated position, and use a javelin that weighs .6 kilograms (1.3 lb).[30] The shot put used by women in this class weighs less than the traditional one at 2 kilograms (4.4 lb) .[31] In the United States, people in this class are allowed to use strapping on the non-throwing hand as a way to anchor themselves to the chair.[2] Athletes in this class who good trunk control and mobility have an advantage over athletes in the same class who have less functional trunk control and mobility. This functional difference can cause different performance results within the same class, with discus throwers with more control in a class able to throw the discus further.[32]

A 1999 study found for people in the F2, F3 and F4 classes in the discus, elbow flexion and shoulder horizontal abduction are equally important variables in the speed at which they release the discus. For F2, F3 and F4 discus throwers, the discus tends to be below shoulder height and the forearm level is generally above elbow height at the moment of release of the discus. F2 and F4 discus throwers have limited shoulder girdle range of motion. F2, F3 and F4 discus throwers have good sitting balance while throwing. F5, F6 and F7 discus throwers have greater angular speed of the shoulder girdle during release of the discus than the lower number classes of F2, F3 and F4. F2 and F4 discus throwers have greater average angular forearm speed than F5, F6, F7 and F8 throwers. F2 and F4 speed is caused by use of the elbow flexion to compensate for the shoulder flexion advantage of F5, F6, F7 and F8 throwers.[32] A study of javelin throwers in 2003 found that F2 throwers have angular speeds of the shoulder girdle less than that of other classes.[30] A study of was done comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 1A (SP1, SP2) and 1B (SP3) in the club throw. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between men in 1A and 1B in the club throw. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between men in 1A and 1B in the discus. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between men in 1A and 1B in the javelin. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between men in 1A and 1B in the shot put. It found there was little significant difference in performance in times between women in 1A and 1B in the 60 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in times between men in 1A and 1B in the 60 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in times between women in 1A and 1B in the slalom. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 1A, 1B and 1C in the discus. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 1A, 1B and 1C in the club throw.[33]

Cycling

F2 sportspeople can participate in cycling. Competitors from this class compete in H2 provided they are a tetraplegic C7/C8 with severe athetosis/ataxia/dystonia, or a tetraplegic with impairments corresponding to a complete cervical lesion at C7/C8 or above.[34][35][36][37] This classification can use an AP2 recumbent, which is a competition cycle that is reclined at 30 degrees and has a rigid frame. This classification can also use an AP3 hand cycle which is inclined at 0 degrees and is reclined on a rigid competition frame.[38] Factoring is used in cycling to allow multiple classes and genders to compete against each other. UCI factoring for 2014 with H4 and H5 men as 100% on the factoring. Against this factoring, H3 men are 97.25% and H3 women are 85.30%. When H3 men are set at 100%, H3 women are 87.71%. When H4 and H5 women are set at 100%, H3 women are 97.25%.[39] In track events, SP2 women in H2 have faster lap times than SP1 men in H1. SP3 men in H3 are significantly faster than SP2 women in H2.[40]

Swimming

Swimmers in this class compete in a number of IPC swimming classes. These include S1, S2, S3, SB3 and S4.[3][41] Swimming classification is done based on a total points system, with a variety of functional and medical tests being used as part of a formula to assign a class. Part of this test involves the Adapted Medical Research Council (MRC) scale. For upper trunk extension, C8 complete are given 0 points.[42]

With classified S1, these swimmers have no hand or wrist flexion so are unable to catch water. Because of a lack of trunk control, they are unstable in the water and have hip drag. As they have no leg and back control, their legs are normally drag in the water in a flexed position. They normally swim the backstroke using a double arm technique. They start in the water with assistance for initial propulsion.[3][42] People with spinal cord injuries in S2 tend to be tetraplegics with complete lesions below C6, or tetraplegics with complete lesions below C7 who have additional paralysis in their plexus or in one arm. These S2 swimmers have no hand or wrist flexion so are unable to catch water. Because of a lack of trunk control, they are unstable in the water and have hip drag. As they have no leg mobility, their legs drag. They normally swim the backstroke as they lack head control to breathe effectively for the freestyle. They start in the water, sometimes with assistance for initial propulsion.[3][42] S3 swimmers tend to have 91 to 115 points, and, for people spinal cord injuries, are tetraplegics with complete lesions below C7 or an incomplete tetraplegic below C6. These S3 swimmers have leg drag when swimming as a result of their hips staying below the surface of the water during a race. Their hand usage is such that they cannot use them effectively to catch water. Because of their disability, they normally start in the water. They make turns by pushing off with their arms.[3][42] People in SB3 tend to be incomplete tetraplegics below C7, complete paraplegics around T1 - T5, or complete paraplegics at T1 - T8 with surgical rods put in their spinal column from T4 to T6. These rods impact their lumbar function and their balance.[42] S4 swimmers tend to be tetraplegics with complete lesions below C8 but have good finger extension, or they are incomplete tetraplegics below C7. These S4 swimmers are able to use their hands and wrists to gain propulsion in the water but have some limits because of lack of full finger control. Because they have no to minimal trunk control, they have leg drag. Their starts are most frequently in the water, and they make turns and start by pushing off the wall using their hands.[42]

For swimming with the most severe disabilities at the 1984 Summer Paralympics, floating devices and a swimming coach in the water swimming next to the Paralympic competitor were allowed.[43] A study of was done comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A (SP1, SP2), 1B (SP3), and 1C (SP3, SP4) in the 25m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A (SP1, SP2), 1B (SP3), and 1C (SP3, SP4) in the 25m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 1A (SP1, SP2), 1B (SP3), and 1C (SP3, SP4) in the 25m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 1A (SP1, SP2), 1B (SP3), and 1C (SP3, SP4) in the 25m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 1A (SP1, SP2), 1B (SP3), and 1C (SP3, SP4) in the 25m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 1A (SP1, SP2), and 1B (SP3) in the 25m breaststroke.[33]

Other sports

One of the sports open to people in this class is archery. People in this class compete in ARW1. This class is for people who have all four of their limbs impacted.[44] Rowing is another option. Rowers in this class may be able to grasp the oar with their hand but have little control of their hands.[45] In 1991, the first internationally accepted adaptive rowing classification system was established and put into use. People from this class were initially classified as Q2, for people with lesions at C7-T1.[46] Ten-pin bowling is another sport open to people in this class, where they compete in TPB8. People in this class do not have more than 70 points for functionality, have normal arm pitch for throwing and use a wheelchair.[47]

This class is eligible to participate in electric wheelchair hockey. The sport has one class and is open to anyone with a spinal injury above T1.[48] Another sport open to this class is wheelchair fencing. Generally, people in this class are classified as 1B. They lack flexion in their fingers, and the weapon has to be strapped to their hand. For international IWF sanctioned competitions, classes are combined. 1A and 1B are combined, competing as Category C.[5]

Getting classified

Classification is often sport specific, and has two parts: a medical classification process and a functional classification process.[49][50][51]

Medical classification for wheelchair sport can consist of medical records being sent to medical classifiers at the international sports federation. The sportsperson's physician may be asked to provide extensive medical information including medical diagnosis and any loss of function related to their condition. This includes if the condition is progressive or stable, if it is an acquired or congenital condition. It may include a request for information on any future anticipated medical care. It may also include a request for any medications the person is taking. Documentation that may be required my include x-rays, ASIA scale results, or Modified Ashworth Scale scores.[52]

One of the standard means of assessing functional classification is the bench test, which is used in swimming, lawn bowls and wheelchair fencing.[50][53][54] Using the Adapted Research Council (MRC) measurements, muscle strength is tested using the bench press for a variety of spinal cord related injuries with a muscle being assessed on a scale of 0 to 5. A 0 is for no muscle contraction. A 1 is for a flicker or trace of contraction in a muscle. A 2 is for active movement in a muscle with gravity eliminated. A 3 is for movement against gravity. A 4 is for active movement against gravity with some resistance. A 5 is for normal muscle movement.[50]

Wheelchair fencing classification has 6 test for functionality during classification, along with a bench test. Each test gives 0 to 3 points. A 0 is for no function. A 1 is for minimum movement. A 2 is for fair movement but weak execution. A 3 is for normal execution. The first test is an extension of the dorsal musculature. The second test is for lateral balance of the upper limbs. The third test measures trunk extension of the lumbar muscles. The fourth test measures lateral balance while holding a weapon. The fifth test measures the trunk movement in a position between that recorded in tests one and three, and tests two and four. The sixth test measures the trunk extension involving the lumbar and dorsal muscles while leaning forward at a 45 degree angle. In addition, a bench test is required to be performed.[54]

References

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- Winnick, Joseph P. (2011-01-01). Adapted Physical Education and Sport. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736089180.

- IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Arenberg, Debbie Hoefler, ed. (February 2015). Guide to Adaptive Rowing (PDF). US Rowing.

- Woude, Luc H. V.; Hoekstra, F.; Groot, S. De; Bijker, K. E.; Dekker, R. (2010-01-01). Rehabilitation: Mobility, Exercise, and Sports : 4th International State-of-the-Art Congress. IOS Press. ISBN 9781607500803.

- "International Wheelchair Rugby Federation : Autonomic Dysreflexia". www.iwrf.com. Retrieved 2016-08-02.

- "About IWAS". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- "Other Sports". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2016-07-30.

- KOCCA (2011). "장애인e스포츠 활성화를 위한 스포츠 등급분류 연구" [Activate e-sports for people with disabilities: Sports Classification Study] (PDF). KOCCA (in Korean). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-17.

- Andrews, David L.; Carrington, Ben (2013-06-21). A Companion to Sport. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118325285.

- Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- "ISMWSF History". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- "IWAS Athletics - Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation". IWASF. IWASF. Retrieved 2016-07-29.

- "IWAS transfer governance of Wheelchair Rugby to IWRF". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- "Explanation of classification in para-sports". International Bowls for the Disabled. International Bowls for the Disabled. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- "New Records in CPISRA Race Running". Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. Int'l Wheelchair & Amputee Sports Federation. 2011. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- Canada, Wheelchair Basketball. "Classification". Wheelchair Basketball Canada. Wheelchair Basketball Canada. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- KOCCA (2011). "장애인e스포츠 활성화를 위한 스포츠 등급분류 연구" [Activate e-sports for people with disabilities: Sports Classification Study] (PDF). KOCCA (in Korean). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-17.

- Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- Thiboutot, Armand; Craven, Philip. The 50th Anniversary of Wheelchair Basketball. Waxmann Verlag. ISBN 9783830954415.

- Chapter 4. 4 - Position Statement on background and scientific rationale for classification in Paralympic sport (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. December 2009.

- Chow, John W.; Kuenster, Ann F.; Lim, Young-tae (2003-06-01). "Kinematic Analysis of Javelin Throw Performed by Wheelchair Athletes of Different Functional Classes". Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2 (2): 36–46. ISSN 1303-2968. PMC 3938047. PMID 24616609.

- Sydney East PSSA (2016). "Para-Athlete (AWD) entry form – NSW PSSA Track & Field". New South Wales Department of Sports. New South Wales Department of Sports. Archived from the original on 2016-09-28.

- Chow, J. W.; Mindock, L. A. (1999). "Discus throwing performances and medical classification of wheelchair athletes". Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 31 (9): 1272–1279. doi:10.1097/00005768-199909000-00007. PMID 10487368.

- van Eijsden-Besseling, M. D. F. (1985). "The (Non)sense of the Present-Day Classification System of Sports for the Disabled, Regarding Paralysed and Amputee Athletes". Paraplegia. International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 23. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "UCI Cycling Regulations - Para cycling" (PDF). Union Cycliste International website. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- "Handcycling". Wheelchair Sports NSW. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- Mitchell, Cassie. "About Paracycling". cassie s. mitchell, ph.d. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- Goosey-Tolfrey, Vicky (2010-01-01). Wheelchair Sport: A Complete Guide for Athletes, Coaches, and Teachers. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736086769.

- Vanlandewijck, Yves; Thompson, Walter R; IOC Medical Commission (2011). The paralympic athlete : handbook of sports medicine and science. Handbook of sports medicine and science. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 34. ISBN 9781444334043. OCLC 642278479.

- "Point 10.11.2 - Para-cycling – Regulations changes proposals" (PDF). UCI. UCI. 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- Thierry, Weissland; Leprêtre, Pierre-Marie (2013-01-01). "Are tetraplegic handbikers going to disappear from team relay in para-cycling?". Frontiers in Physiology. 4: 77. doi:10.3389/fphys.2013.00077. PMC 3620554. PMID 23576995.

- Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04.

- Broekhoff, Jan (1986-06-01). The 1984 Olympic Scientific Congress proceedings: Eugene, Ore., 19-26 July 1984 : (also: OSC proceedings). Human Kinetics Publishers. ISBN 9780873220064.

- Gil, Ana Luisa (2013). Management of Paralympics Games: Problems and perspectives. Brno, Czech Republic: Faculty of Sport studies, Department of Social Sciences in Sport And Department of Health Promotion, MASARYK UNIVERSITY.

- Arenberg, Debbie Hoefler, ed. (February 2015). Guide to Adaptive Rowing (PDF). US Rowing.

- Stichting Roeivalidatie (1991). International Symposium Adaptive Rowing Amsterdam June, 26-27 1991. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Stichting Roeivalidatie. p. 21. OCLC 221080358.

- KOCCA (2011). "장애인e스포츠 활성화를 위한 스포츠 등급분류 연구" [Activate e-sports for people with disabilities: Sports Classification Study] (PDF). KOCCA (in Korean). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-17.

- IWAS Committee Electric Wheelchair Hockey (ICEWH) (July 2014). "REPORT CLASSIFICATION PROCESS" (PDF). IWAS Committee Electric Wheelchair Hockey (ICEWH). IWAS. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- "CLASSIFICATION GUIDE" (PDF). Swimming Australia. Swimming Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- "Bench Press Form". International Disabled Bowls. International Disabled Bowls. Retrieved July 29, 2016.

- IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- "Medical Diagnostic Form" (PDF). IWAS. IWAS. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- "CLASSIFICATION GUIDE" (PDF). Swimming Australia. Swimming Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).