F57 (classification)

F57 is a disability sport classification for disability athletics for people who compete in field events from a seated position. This class is for people with limb deficiencies not covered by other classes. It includes people who are members of the ISOD A1 and A9 classes. Events open to people in this class include the shot put, discus and javelin.

Definition

International Paralympic Committee defined this classification on their website in July 2016, " Athletes who meet one or more of the MDC for impaired muscle power, limb deficiency, impaired passive range of movement and leg length difference, who do not fit any of the previously described profiles, fall into this class."[1] The Spectator Guide for the Rio Paralympics defines the class as, "wheelchair athletes (effects of polio, spinal cord injuries and amputations)"[2] People competing in the seated position in this class have mobility limitations that cannot exceed 70 points.[3]

Disability groups

Both people with amputations and spinal cord injuries compete in this class.

Amputees

People who are amputees compete in this class, including ISOD A1 and A9.[4][5] In general, track athletes with amputations in should be considerate of the surface they are running on, and avoid asphalt and cinder tracks.[5] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training, amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[5]

Lower limb amputees

ISOD A1 classified athletes participate in T54, F56, F57 and F58.[4][5][6] The nature of a person's amputations in this class can effect their physiology and sports performance.[5][7][8] Lower limb amputations effect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[8] People in this class use around 120% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation.[8]

A study was done comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was no significant difference in performance in times between women in A1, A2 and A3 in the discus, women in A1 and A2 in the javelin, women in A1 and A2 in the 100 meter race, men in A1, A2 and A3 in the discus, men in A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, A6, A7, A8 and A9 in the javelin, men in A1, A2 and A3 in the shot put, men in A1 and A2 in the 100 meter race, and men in A1, A2, A3 and A4 in the 400 meter race.[9] Double below the knee amputees also have a competitive advantage when compared to double above the knee amputees.[10] From the 2004 Summer Paralympics to the 2012 Summer Paralympics, there was no significant changes in performance times put up by male sprinters in 100 meter, 200 meter and 400 meter events.[10]

Upper and lower limb amputees

Members of the ISOD A9 class compete in T42, T43, T44, F42, F43, F44, F56, F57, and F58.[4][5] The nature of an A9 athletes's amputations can effect their physiology and sports performance.[5][8] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training, amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[5] Lower limb amputations effect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[8] Because they are missing a limb, amputees are more prone to overuse injuries in their remaining limbs. Common problems with intact upper limbs for people in this class include rotator cuffs tearing, shoulder impingement, epicondylitis and peripheral nerve entrapment.[8]

Les Autres

People who are Les Autres compete in this class. This includes LAF3 classified athletes.[4][11] In general, Les Autres classes cover sportspeople with locomotor disabilities regardless of their diagnosis.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

LAF3

In athletics, LAF3 competitors compete in F54, F55, F56, F57 and F58 events. These are wheelchair athletics classes.[4][18][19] Athletes in this class have normal functioning in their throwing arm. While throwing, they can generally maintain good balance.[18] Competitors in this class may also compete in T44. This is a standing class for people with weakness in one leg muscle or who have joint restrictions.[4] At the 1984 Summer Paralympics, LAF1, LAF2 and LAF3 track athletes had the 60 meters and 400 meter distances on the program.[4] There was a large range of sportspeople with different disabilities in this class at the 1984 Summer Paralympics.[4]

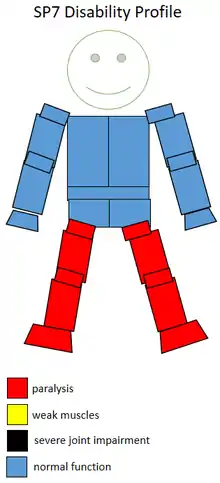

LAF3 is an Les Autres sports classification.[4][20] Sportspeople in this class use wheelchairs on a regular basis as a result of reduced muscle function. They have normal trunk functionality, balance and use of their upper limbs.[20] Medically, this class includes people with hemiparesis, and hip and knee stiffness with deformation in one arm. It means they have limited function in at least two limbs. In terms of functional classification, this means the sportsperson uses a wheelchair, has good sitting balance and has good arm function.[21] For the 1984 Summer Paralympics, LAF3 was defined by the Games organizers as, "Wheelchair bound with normal arm function and good sitting balance."[22]

Spinal cord injuries

People with spinal cord injuries compete in this class, including F7 sportspeople.[23][24]

F7

F7 is wheelchair sport classification, that corresponds to the neurological level S1 - S2.[23][25] Historically, this class has been called Lower 5.[23][25] In 2002, USA Track & Field defined this class as, "These athletes also have the ability to move side to side, so they can throw across their body. They usually can bend one hip backward to push the thigh into the chair, and can bend one ankle downward to push down with the foot. Neurological level: S1-S2."[26]

People with a lesion at S1 have their hamstring and peroneal muscles effected. Functionally, they can bend their knees and lift their feet. They can walk on their own, though they may require ankle braces or orthopedic shoes. They can generally change in any physical activity.[27] People with lesions at the L4 to S2 who are complete paraplegics may have motor function issues in their gluts and hamstrings. Their quadriceps are likely to be unaffected. They may be absent sensation below the knees and in the groin area.[28]

Disabled Sports USA defined the functional definition of this class in 2003 as, "Have very good sitting balance and movements in the backwards and forwards plane. Usually have very good balance and movements towards one side (side to side movements) due to presence of one functional hip abductor, on the side that movement is towards. Usually can bend one hip backwards; i.e. push the thigh into the chair. Usually can bend one ankle downwards; ie. push the foot onto the foot plate. The side that is strong is important when considering how much it will help functional performance."[23]

Field events open to this class have included shot put, discus and javelin.[23][24] In pentathlon, the events for this class have included Shot, Javelin, 200m, Discus, 1500m.[23] F7 throwers compete from a seated position. The javelin they throw weighs .6 kilograms (1.3 lb).[29] The shot put used by women in this class weighs less than the traditional one at 3 kilograms (6.6 lb).[30]

There are performance differences and similarities between this class and other wheelchair classes. A study of javelin throwers in 2003 found that F7 throwers have angular speeds of the shoulder girdle similar to that of F4 to F9 throwers.[29] A 1999 study of discus throwers found that for F5 to F8 discus throwers, the upper arm tends to be near horizontal at the moment of release of the discus. F5 to F7 discus throwers have greater angular speed of the shoulder girdle during release of the discus than the lower number classes of F2 to F4. F5 and F8 discus throwers have less average angular forearm speed than F2 and F4 throwers. F2 and F4 speed is caused by use of the elbow flexion to compensate for the shoulder flexion advantage of F5 to F8 throwers.[31] A study of was done comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 2 (SP4), 3 (SP4, SP5), 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the discus. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between men in 3, 4, 5 and 6 in the 200 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between women in 3, 4 and 5 in the 60 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 4, 5 and 6 in the discus. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 4, 5 and 6 in the javelin. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 4, 5 and 6 in the shot put. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 4, 5 and 6 in the discus. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between women in 4, 5 and 6 in the 60 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between women in 4, 5 and 6 in the 800 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between women in 4, 5 and 6 in the 1,500 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between women in 4, 5 and 6 in the slalom. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between men in 4, 5 and 6 in the discus. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between men in 4, 5 and 6 in the shot put. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between men in 4, 5 and 6 in the 100 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between men in 4, 5 and 6 in the 800 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between men in 4, 5 and 6 in the 1,500 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between men in 4, 5 and 6 in the slalom. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between women in 5 and 6 in the discus. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between women in 5 and 6 in the 60 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between women in 5 and 6 in the 100 meters. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between men in 5 and 6 in the javelin. It found there was little significant difference in performance in distance between men in 5 and 6 in the shot put. It found there was little significant difference in performance in time between men in 5 and 6 in the 100 meters.[9]

Performance and rules

Athletes in this class used secure frames for throwing events. The frame can be only one of two shapes: A rectangle or square. The sides must be at least 30 centimetres (12 in) long. The seat needs to be lower at the back or level, and it cannot be taller than 75 centimetres (30 in). This height includes any cushioning or padding.[32] Throwers can have footplates on their frames, but the footplate can only be used for stability. It cannot be used to push off from. Rests can be used on the frame but they need to be present only for safety reasons and to aide in athlete stability. They need to be manufactured from rigid materials that do not move. These materials may include steel or aluminum. The backrest can have cushioning but it cannot be thicker than 5 centimetres (2.0 in). It cannot have any movable parts. The frame can also have a holding bar. The holding bar needs to be round or square, and needs to be a single straight piece. Athletes are not required to use a holding bar during their throw, and they can hold on to any part of the frame during their throw.[32] Throwing frames should be inspected prior to the event. This should be done either in the call room or in the competition area.[32] In general, people in this class should be allocated around 2 minutes to set up their chair.[32]

Athletes need to throw from a seated position. They cannot throw from an inclined or other position. Doing so could increase the contribution of their legs and benefit their performance. Their legs must be in contact with the seat during the throw. If an athlete throws from a non-seated position, this is counted as a foul.[32] People in this class cannot put tape on their hands.[32]

All straps used to hold the athlete to the frame must be non-elastic. While in the process of throwing, an athlete cannot touch a tie-down for the frame. Because of visibility issues for officials, athletes cannot wear lose clothing and they can ask athletes to tuck in clothing if they feel there is any issue with visibility. In throwing events at the Paralympic Games and World Championships, athletes get three trial throws. After that, the top 8 throwers get an additional three throws. For other events, organizers generally have the option to use that formula to give all throwers six consecutive throws. The total number of warm-up throws is at the discretion of the meet director.[32]

At the Paralympic Games

For the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio, the International Paralympic Committee had a zero classification at the Games policy. This policy was put into place in 2014, with the goal of avoiding last minute changes in classes that would negatively impact athlete training preparations. All competitors needed to be internationally classified with their classification status confirmed prior to the Games, with exceptions to this policy being dealt with on a case-by-case basis.[33] In case there was a need for classification or reclassification at the Games despite best efforts otherwise, athletics classification was scheduled for September 4 and September 5 at Olympic Stadium. For sportspeople with physical or intellectual disabilities going through classification or reclassification in Rio, their in competition observation event is their first appearance in competition at the Games.[33]

Events

Competitors in this class compete in shot put, discus and javelin.[34]

Becoming classified

For this class, classification generally has four phase. The first stage of classification is a health examination. For amputees in this class, this is often done on site at a sports training facility or competition. The second stage is observation in practice, the third stage is observation in competition and the last stage is assigning the sportsperson to a relevant class.[35] Sometimes the health examination may not be done on site because the nature of the amputation could cause not physically visible alterations to the body. This is especially true for lower limb amputees as it relates to how their limbs align with their hips and the impact this has on their spine and how their skull sits on their spine.[36] During the observation phase involving training or practice, all athletes in this class may be asked to demonstrate their skills in athletics, such as running, jumping or throwing. A determination is then made as to what classification an athlete should compete in. Classifications may be Confirmed or Review status. For athletes who do not have access to a full classification panel, Provisional classification is available; this is a temporary Review classification, considered an indication of class only, and generally used only in lower levels of competition.[37]

While some people in this class may be ambulatory, they generally go through the classification process while using a wheelchair. This is because they often compete from a seated position.[38] Failure to do so could result in them being classified as an ambulatory class competitor.[38] For people in this class with amputations, classification is often based on the anatomical nature of the amputation.[7][39] The classification system takes several things into account when putting people into this class. These includes which limbs are effected, how many limbs are effected, and how much of a limb is missing.[40][41]

Competitors

Sportspeople competing in this class include Mexico's Angeles Ortiz Hernandez, Ireland's Orla Barry and Algeria's Nassima Saifi.[42]

References

- "IPC Athletics Classification & Categories". www.paralympic.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- "Athletics Spectator Guide - 2012 Rio Games" (PDF). Rio 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- Starkey, Chad; Johnson, Glen (2006-01-01). Athletic Training and Sports Medicine. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780763705367.

- "CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY". Queensland Sport. Queensland Sport. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- "Classification 101". Blaze Sports. Blaze Sports. June 2012. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- DeLisa, Joel A.; Gans, Bruce M.; Walsh, Nicholas E. (2005-01-01). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781741309.

- Miller, Mark D.; Thompson, Stephen R. (2014-04-04). DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455742219.

- van Eijsden-Besseling, M. D. F. (1985). "The (Non)sense of the Present-Day Classification System of Sports for the Disabled, Regarding Paralysed and Amputee Athletes". Paraplegia. International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 23. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- Hassani, Hossein; Ghodsi, Mansi; Shadi, Mehran; Noroozi, Siamak; Dyer, Bryce (2015-06-16). "An Overview of the Running Performance of Athletes with Lower-Limb Amputation at the Paralympic Games 2004–2012". Sports. 3 (2): 103–115. doi:10.3390/sports3020103.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- Tweedy, S. M. (2003). The ICF and Classification in Disability Athletics. In R. Madden, S. Bricknell, C. Sykes and L. York (Ed.), ICF Australian User Guide, Version 1.0, Disability Series (pp. 82-88)Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- Albrecht, Gary L. (2005-10-07). Encyclopedia of Disability. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781452265209.

- "Paralympic classifications explained". ABC News Sport. 2012-08-31. Retrieved 2016-07-31.

- Sportbond, Nederlandse Invaliden (1985-01-01). Proceedings of the Workshop on Disabled and Sports. Nederlandse Invaliden Sportbond.

- Narvani, A. A.; Thomas, P.; Lynn, B. (2006-09-27). Key Topics in Sports Medicine. Routledge. ISBN 9781134220618.

- Hunter, Nick (2012-02-09). The Paralympics. Hachette Children's Group. ISBN 9780750270458.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- International Paralympic Committee (June 2009). "IPC Athletics Classification Project for Physical Impairments: Final Report - Stage 1" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Governing Committee Reports.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- MD, Michael A. Alexander; MD, Dennis J. Matthews (2009-09-18). Pediatric Rehabilitation: Principles & Practices, Fourth Edition. Demos Medical Publishing. ISBN 9781935281658.

- Broekhoff, Jan (1986-06-01). The 1984 Olympic Scientific Congress proceedings: Eugene, Ore., 19-26 July 1984 : (also: OSC proceedings). Human Kinetics Publishers. ISBN 9780873220064.

- National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- Winnick, Joseph P. (2011-01-01). Adapted Physical Education and Sport. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736089180.

- Goosey-Tolfrey, Vicky (2010-01-01). Wheelchair Sport: A Complete Guide for Athletes, Coaches, and Teachers. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736086769.

- Chow, John W.; Kuenster, Ann F.; Lim, Young-tae (2003-06-01). "Kinematic Analysis of Javelin Throw Performed by Wheelchair Athletes of Different Functional Classes". Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2 (2): 36–46. ISSN 1303-2968. PMC 3938047. PMID 24616609.

- Sydney East PSSA (2016). "Para-Athlete (AWD) entry form – NSW PSSA Track & Field". New South Wales Department of Sports. New South Wales Department of Sports. Archived from the original on 2016-09-28.

- Chow, J. W., & Mindock, L. A. (1999). Discus throwing performances and medical classification of wheelchair athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise,31(9), 1272-1279. doi:10.1097/00005768-199909000-00007

- "PARALYMPIC TRACK & FIELD: Officials Training" (PDF). USOC. United States Olympic Committee. December 11, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- "Rio 2016 Classification Guide" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. March 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- Winnick, Joseph P. (2011-01-01). Adapted Physical Education and Sport. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736089180.

- Tweedy, Sean M.; Beckman, Emma M.; Connick, Mark J. (August 2014). "Paralympic Classification: Conceptual Basis, Current Methods, and Research Update". Paralympic Sports Medicine and Science. 6 (85). Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- Gilbert, Keith; Schantz, Otto J.; Schantz, Otto (2008-01-01). The Paralympic Games: Empowerment Or Side Show?. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. ISBN 9781841262659.

- "CLASSIFICATION Information for Athletes" (PDF). Sydney Australia: Australian Paralympic Committee. 2 July 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Cashman, Richmard; Darcy, Simon (2008-01-01). Benchmark Games. Benchmark Games. ISBN 9781876718053.

- Pasquina, Paul F.; Cooper, Rory A. (2009-01-01). Care of the Combat Amputee. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160840777.

- Tweedy, Sean M. (2002). "Taxonomic Theory and the ICF: Foundations for a Unified Disability Athletics Classification" (PDF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 19 (2): 220–237. doi:10.1123/apaq.19.2.220. PMID 28195770. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 17, 2016. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- International Sports Organization for the Disabled. (1993). Handbook. Newmarket, ON: Author. Available Federacion Espanola de Deportes de Minusvalidos Fisicos, c/- Ferraz, 16 Bajo, 28008 Madrid, Spain.

- "IPC World Rankings - Athletics". www.paralympic.org. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

.svg.png.webp)