FANCL

E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase FANCL is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the FANCL gene.[5]

| FANCL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | FANCL, FAAP43, PHF9, POG, Fanconi anemia complementation group L, FA complementation group L | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 608111 MGI: 1914280 HomoloGene: 9987 GeneCards: FANCL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Function

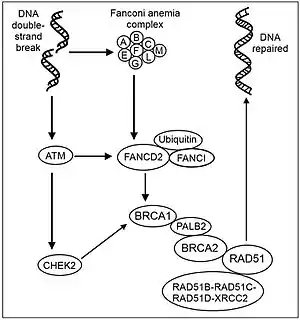

The clinical phenotype of mutational defects in all Fanconi anemia (FA) complementation groups is similar. This phenotype is characterized by progressive bone marrow failure, cancer proneness and typical birth defects.[13] The main cellular phenotype is hypersensitivity to DNA damage, particularly inter-strand DNA crosslinks.[14] The FA proteins interact through a multi-protein pathway. DNA interstrand crosslinks are highly deleterious damages that are repaired by homologous recombination involving coordination of FA proteins and breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1).

The Fanconi Anemia (FA) DNA repair pathway is essential for the recognition and repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICL). A critical step in the pathway is the monoubiquitination of FANCD2 by the RING E3 ligase FANCL. FANCL comprises 3 domains, a RING domain that interacts with E2 conjugating enzymes, a central domain required for substrate interaction, and an N-terminal E2-like fold (ELF) domain that interacts with FANCB.[15] The ELF domain of FANCL is also required to mediate a non-covalent interaction between FANCL and ubiquitin. The ELF domain is required to promote efficient DNA damage-induced FANCD2 monoubiquitination in vertebrate cells, suggesting an important function of FANCB and ubiquitin binding by FANCL in vivo.[16]

A nuclear complex containing FANCL (as well as FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG and FANCM) is essential for the activation of the FANCD2 protein to the mono-ubiquitinated isoform.[6] In normal, non-mutant, cells FANCD2 is mono-ubiquinated in response to DNA damage. Activated FANCD2 protein co-localizes with BRCA1 (breast cancer susceptibility protein) at ionizing radiation-induced foci and in synaptonemal complexes of meiotic chromosomes (see Figure: Recombinational repair of double strand damage).

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000115392 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000004018 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Entrez Gene: FANCL Fanconi anemia, complementation group L".

- D'Andrea AD (2010). "Susceptibility pathways in Fanconi's anemia and breast cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (20): 1909–19. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0809889. PMC 3069698. PMID 20484397.

- Sobeck A, Stone S, Landais I, de Graaf B, Hoatlin ME (2009). "The Fanconi anemia protein FANCM is controlled by FANCD2 and the ATR/ATM pathways". J. Biol. Chem. 284 (38): 25560–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.007690. PMC 2757957. PMID 19633289.

- Castillo P, Bogliolo M, Surralles J (2011). "Coordinated action of the Fanconi anemia and ataxia telangiectasia pathways in response to oxidative damage". DNA Repair (Amst.). 10 (5): 518–25. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.02.007. PMID 21466974.

- Stolz A, Ertych N, Bastians H (2011). "Tumor suppressor CHK2: regulator of DNA damage response and mediator of chromosomal stability". Clin. Cancer Res. 17 (3): 401–5. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1215. PMID 21088254.

- Taniguchi T, Garcia-Higuera I, Andreassen PR, Gregory RC, Grompe M, D'Andrea AD (2002). "S-phase-specific interaction of the Fanconi anemia protein, FANCD2, with BRCA1 and RAD51". Blood. 100 (7): 2414–20. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-01-0278. PMID 12239151.

- Park JY, Zhang F, Andreassen PR (2014). "PALB2: the hub of a network of tumor suppressors involved in DNA damage responses". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1846 (1): 263–75. doi:10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.06.003. PMC 4183126. PMID 24998779.

- Chun J, Buechelmaier ES, Powell SN (2013). "Rad51 paralog complexes BCDX2 and CX3 act at different stages in the BRCA1-BRCA2-dependent homologous recombination pathway". Mol. Cell. Biol. 33 (2): 387–95. doi:10.1128/MCB.00465-12. PMC 3554112. PMID 23149936.

- Walden, Helen; Deans, Andrew J. (2014). "The Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway: structural and functional insights into a complex disorder". Annual Review of Biophysics. 43: 257–278. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-022737. ISSN 1936-1238. PMID 24773018.

- Deans, Andrew J.; West, Stephen C. (2011-06-24). "DNA interstrand crosslink repair and cancer". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 11 (7): 467–480. doi:10.1038/nrc3088. ISSN 1474-1768. PMC 3560328. PMID 21701511.

- van Twest, Sylvie; Murphy, Vincent J.; Hodson, Charlotte; Tan, Winnie; Swuec, Paolo; O'Rourke, Julienne J.; Heierhorst, Jörg; Crismani, Wayne; Deans, Andrew J. (2017-01-19). "Mechanism of Ubiquitination and Deubiquitination in the Fanconi Anemia Pathway". Molecular Cell. 65 (2): 247–259. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.005. ISSN 1097-4164. PMID 27986371.

- Miles JA, Frost MG, Carroll E, Rowe ML, Howard MJ, Sidhu A, Chaugule VK, Alpi AF, Walden H (2015). "The Fanconi Anemia DNA Repair Pathway Is Regulated by an Interaction between Ubiquitin and the E2-like Fold Domain of FANCL". J. Biol. Chem. 290 (34): 20995–1006. doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.675835. PMC 4543658. PMID 26149689.

Further reading

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–4. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, et al. (1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–56. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- Agoulnik AI, Lu B, Zhu Q, et al. (2003). "A novel gene, Pog, is necessary for primordial germ cell proliferation in the mouse and underlies the germ cell deficient mutation, gcd". Hum. Mol. Genet. 11 (24): 3047–53. doi:10.1093/hmg/11.24.3047. PMID 12417526.

- Strausberg RL, Feingold EA, Grouse LH, et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916899M. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Lu B, Bishop CE (2003). "Mouse GGN1 and GGN3, two germ cell-specific proteins from the single gene Ggn, interact with mouse POG and play a role in spermatogenesis". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (18): 16289–96. doi:10.1074/jbc.M211023200. PMID 12574169.

- Lu B, Bishop CE (2004). "Late onset of spermatogenesis and gain of fertility in POG-deficient mice indicate that POG is not necessary for the proliferation of spermatogonia". Biol. Reprod. 69 (1): 161–8. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.102.014654. PMID 12606378.

- Meetei AR, Sechi S, Wallisch M, et al. (2003). "A Multiprotein Nuclear Complex Connects Fanconi Anemia and Bloom Syndrome". Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (10): 3417–26. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.10.3417-3426.2003. PMC 164758. PMID 12724401.

- Meetei AR, de Winter JP, Medhurst AL, et al. (2003). "A novel ubiquitin ligase is deficient in Fanconi anemia". Nat. Genet. 35 (2): 165–70. doi:10.1038/ng1241. PMID 12973351. S2CID 10149290.

- Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, et al. (2004). "Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs". Nat. Genet. 36 (1): 40–5. doi:10.1038/ng1285. PMID 14702039.

- Gerhard DS, Wagner L, Feingold EA, et al. (2004). "The Status, Quality, and Expansion of the NIH Full-Length cDNA Project: The Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Res. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Meetei AR, Levitus M, Xue Y, et al. (2004). "X-linked inheritance of Fanconi anemia complementation group B". Nat. Genet. 36 (11): 1219–24. doi:10.1038/ng1458. PMID 15502827.

- Hillier LW, Graves TA, Fulton RS, et al. (2005). "Generation and annotation of the DNA sequences of human chromosomes 2 and 4". Nature. 434 (7034): 724–31. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..724H. doi:10.1038/nature03466. PMID 15815621.

- Meetei AR, Medhurst AL, Ling C, et al. (2005). "A Human Orthologue of Archaeal DNA Repair Protein Hef is Defective in Fanconi Anemia Complementation Group M". Nat. Genet. 37 (9): 958–63. doi:10.1038/ng1626. PMC 2704909. PMID 16116422.

- Gurtan AM, Stuckert P, D'Andrea AD (2006). "The WD40 repeats of FANCL are required for Fanconi anemia core complex assembly". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (16): 10896–905. doi:10.1074/jbc.M511411200. PMID 16474167.

- Zhang J, Wang X, Lin CJ, et al. (2007). "Altered expression of FANCL confers mitomycin C sensitivity in Calu-6 lung cancer cells". Cancer Biol. Ther. 5 (12): 1632–6. doi:10.4161/cbt.5.12.3351. PMID 17106252.