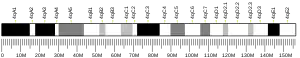

ISG15

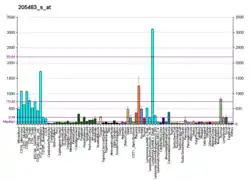

Interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) is a 17 kDA secreted protein that in humans is encoded by the ISG15 gene.[5][6] ISG15 is induced by type I interferon (IFN) and serves many functions, acting both as an extracellular cytokine and an intracellular protein modifier. The precise functions are diverse and vary among species but include potentiation of Interferon gamma (IFN-II) production in lymphocytes, ubiquitin-like conjugation to newly-synthesized proteins and negative regulation of the IFN-I response.[7]

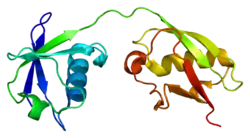

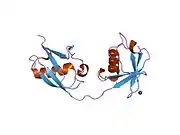

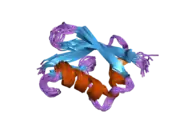

Structure

The ISG15 gene consists of two exons and encodes for a 17 kDa polypeptide. The immature polypeptide is cleaved at its carboxy terminus, generating a mature 15 kDa product that terminates with a LRLRGG motif, as found in ubiquitin. The tertiary structure of ISG15 also resembles ubiquitin, despite only ~30% sequence identity. Specifically, this structure consists of two ubiquitin-like domains connected by a polypeptide ‘hinge.’ Of note, ISG15 shows substantial sequence variation among species, with homology as low as 30% between orthologs.[8]

Function

After induction by type I interferon, ISG15 can be found in three forms, each with unique functions:

Extracellular cytokine

ISG15 is secreted from the cell and can be detected in supernatant or blood plasma.[9][10] ISG15 binds the LFA-1 integrin receptor on NK- and T-cells to potentiate their production of IFN-II,[11][12] which is essential for mycobacterial immunity.

Intracellular conjugate: ISGylation

In a ubiquitin-like fashion, ISG15 is covalently linked by its C-terminal LRLRGG motif to lysine residues on newly synthesized proteins. This process, termed ISGylation, is catalyzed by a series of conjugating enzymes. The activating E1 enzyme (UBE1L) charges ISG15 by forming a high-energy thiolester intermediate and transfers it to the UbcH8 E2 enzyme. UbcH8 has been identified as the major E2 for ISGylation, although it also functions in ubiquitination. The E2 protein subsequently transfers the ISG15 to specific E3 ligases (Herc5[13]) and relevant intracellular substrates. Only one deconjugating protease with specificity to ISG15 has been identified to date: USP18 (a member of the USP family) cleaves ISG15-peptide fusions and also removes ISG15 (deISGylation) from native conjugates.[14] The effects of ISGylation are incompletely understood and involve both activation and inhibition of antiviral immunity.

Free intracellular molecule

Unconjugated ISG15 negatively regulates IFN-I signaling by preventing the SKP2-mediated proteasomal degradation of USP18, a direct inhibitor of the IFN-I receptor.[15] Absence of ISG15 leads to persistent IFN-I signaling in human, but not mouse, systems.[16]

Clinical significance

ISG15-deficiency is a very rare genetic disorder caused by mutations of the ISG15 gene. It is inherited with an autosomal recessive pattern and is classified as a primary immunodeficiency or inborn error of immunity. Patients present in childhood with infectious, neurologic or dermatologic features. Basal ganglia calcification is observed in all patients reported to date and represents the underlying autoinflammatory disease of excessive IFN-I activity, known as type I interferonopathy.[15] The basal ganglia calcifications may cause epileptic seizures but often are asymptomatic. The IFN-I inflammation may also manifest early in life as ulcerative skin lesions in the armpit, groin and neck regions.[17] Finally, ISG15-deficiency leads to mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease,[12] although with incomplete penetrance. These infections present as fistulizing lymphadenopathies and respiratory symptoms following BCG vaccination.

In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, tumor-associated macrophages secrete ISG15 enhancing the phenotype of cancer stem cells in the tumor.[18]

History

ISG15 was originally identified in the late 1970s as a 15-kDa protein produced in response to type I interferon, a potent class of antiviral cytokines.[19] Given the molecular weight, it was originally termed ‘a 15-kDa protein’, but later renamed interferon-stimulated-gene-15 when the cassette of interferon-stimulated genes were recognized.[20][21] In 1987 it was identified that ISG15 cross-reacts with anti-ubiquitin antibodies, and subsequent experiments uncovered the ubiquitin-like conjugation of ISG15 to other cellular proteins, coined ‘ISGylation’.[22][23] Given its inducibility by IFN-I, studies in the following decades focused on the antiviral activity of ISG15. These studies were carried out predominantly with in vitro systems and mouse models, and ascribed several antiviral functions to ISGylation. During this time, it was also discovered that ISG15 could be detected outside of cells.[9] and in human serum samples.[10] This free form of ISG15 could stimulate IFN-II production in lymphocytes.[11] Finally, ISG15 could also be detected as an un-conjugated intracellular molecule with functions independent of ISGylation.[24]

The discovery of humans deficient in ISG15 elucidated the importance of these functions in human biology. ISG15-deficient patients were first identified by their susceptibly to BCG-strain mycobacteria, owing to the essential function of free ISG15 to potentiate the IFN-gamma / Interleukin-12 axis[12] Surprisingly, despite the IFN-inducible nature of ISG15 and the previously-ascribed antiviral functions in mice, ISG15-deficient patients showed no susceptibility to viral infections.[12] In fact, follow-up studies uncovered enhanced type I IFN signatures, manifesting as basal ganglia calcifications akin to TORCH infection but without an infectious etiology.[15] This persistent, low-level inflammation was later shown to confer enhanced resistance to a wide array of viruses.[16] This phenotype results from a previously-unrecognized function of ISG15 to negatively regulate IFN signaling, which is absent in murine systems. Other higher-order mammals (e.g. pig and dog), however, have achieved this negative regulatory function of ISG15, seemingly by convergent evolution.[25]

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000187608 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000035692 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Blomstrom DC, Fahey D, Kutny R, Korant BD, Knight E (July 1986). "Molecular characterization of the interferon-induced 15-kDa protein. Molecular cloning and nucleotide and amino acid sequence". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 261 (19): 8811–6. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)84453-8. PMID 3087979.

- "Entrez Gene: ISG15 ISG15 ubiquitin-like modifier".

- Subedi P, Huber K, Sterr C, Dietz A, Strasser L, Kaestle F, Hauck SM, Duchrow L, Aldrian C, Monroy Ordonez EB, Luka B, Thomsen AR, Henke M, Gomolka M, Rossler U, Azimzadeh O, Moertl S, Hornhardt S (June 2023). "Towards unravelling biological mechanisms behind radiation-induced oral mucositis via mass spectrometry-based proteomics". Frontiers in Oncology. 13. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1180642. PMC 10298177. PMID 37384298.

- Dzimianski JV, Scholte FE, Bergeron É, Pegan SD (October 2019). "ISG15: It's Complicated". Journal of Molecular Biology. 431 (21): 4203–4216. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2019.03.013. PMC 6746611. PMID 30890331.

- Knight E, Cordova B (April 1991). "IFN-induced 15-kDa protein is released from human lymphocytes and monocytes". Journal of Immunology. 146 (7): 2280–4. PMID 2005397.

- D'Cunha J, Knight E, Haas AL, Truitt RL, Borden EC (January 1996). "Immunoregulatory properties of ISG15, an interferon-induced cytokine". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (1): 211–5. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93..211D. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.1.211. PMC 40208. PMID 8552607.

- Recht M, Borden EC, Knight E (October 1991). "A human 15-kDa IFN-induced protein induces the secretion of IFN-gamma". Journal of Immunology. 147 (8): 2617–23. PMID 1717569.

- Swaim CD, Scott AF, Canadeo LA, Huibregtse JM (November 2017). "Extracellular ISG15 Signals Cytokine Secretion through the LFA-1 Integrin Receptor". Molecular Cell. 68 (3): 581–590.e5. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.003. PMC 5690536. PMID 29100055.

- Woods MW, Kelly JN, Hattlmann CJ, Tong JG, Xu LS, Coleman MD, et al. (November 2011). "Human HERC5 restricts an early stage of HIV-1 assembly by a mechanism correlating with the ISGylation of Gag". Retrovirology. 8: 95. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-8-95. PMC 3228677. PMID 22093708.

- Malakhov MP, Malakhova OA, Kim KI, Ritchie KJ, Zhang DE (March 2002). "UBP43 (USP18) specifically removes ISG15 from conjugated proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (12): 9976–81. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109078200. PMID 11788588.

- Zhang X, Bogunovic D, Payelle-Brogard B, Francois-Newton V, Speer SD, Yuan C, et al. (January 2015). "Human intracellular ISG15 prevents interferon-α/β over-amplification and auto-inflammation". Nature. 517 (7532): 89–93. Bibcode:2015Natur.517...89Z. doi:10.1038/nature13801. PMC 4303590. PMID 25307056.

- Speer SD, Li Z, Buta S, Payelle-Brogard B, Qian L, Vigant F, et al. (May 2016). "ISG15 deficiency and increased viral resistance in humans but not mice". Nature Communications. 7: 11496. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711496S. doi:10.1038/ncomms11496. PMC 4873964. PMID 27193971.

- Martin-Fernandez M, Bravo García-Morato M, Gruber C, Murias Loza S, Malik MN, Alsohime F, et al. (May 2020). "Systemic Type I IFN Inflammation in Human ISG15 Deficiency Leads to Necrotizing Skin Lesions". Cell Reports. 31 (6): 107633. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107633. PMC 7331931. PMID 32402279.

- Sainz B, Martín B, Tatari M, Heeschen C, Guerra S (December 2014). "ISG15 is a critical microenvironmental factor for pancreatic cancer stem cells". Cancer Research. 74 (24): 7309–20. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1354. PMID 25368022.

- Farrell PJ, Broeze RJ, Lengyel P (June 1979). "Accumulation of an mRNA and protein in interferon-treated Ehrlich ascites tumour cells". Nature. 279 (5713): 523–5. Bibcode:1979Natur.279..523F. doi:10.1038/279523a0. PMID 571963. S2CID 4317436.

- Kessler DS, Levy DE, Darnell JE (November 1988). "Two interferon-induced nuclear factors bind a single promoter element in interferon-stimulated genes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 85 (22): 8521–5. Bibcode:1988PNAS...85.8521K. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.22.8521. PMC 282490. PMID 2460869.

- Reich N, Evans B, Levy D, Fahey D, Knight E, Darnell JE (September 1987). "Interferon-induced transcription of a gene encoding a 15-kDa protein depends on an upstream enhancer element". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 84 (18): 6394–8. Bibcode:1987PNAS...84.6394R. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.18.6394. PMC 299082. PMID 3476954.

- Haas AL, Ahrens P, Bright PM, Ankel H (August 1987). "Interferon induces a 15-kilodalton protein exhibiting marked homology to ubiquitin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 262 (23): 11315–23. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)60961-5. PMID 2440890.

- Loeb KR, Haas AL (April 1992). "The interferon-inducible 15-kDa ubiquitin homolog conjugates to intracellular proteins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (11): 7806–13. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)42585-9. PMID 1373138.

- Werneke SW, Schilte C, Rohatgi A, Monte KJ, Michault A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, et al. (October 2011). "ISG15 is critical in the control of Chikungunya virus infection independent of UbE1L mediated conjugation". PLOS Pathogens. 7 (10): e1002322. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002322. PMC 3197620. PMID 22028657.

- Qiu X, Taft J, Bogunovic D (March 2020). "Developing Broad-Spectrum Antivirals Using Porcine and Rhesus Macaque Models". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 221 (6): 890–894. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiz549. PMC 7050986. PMID 31637432.

Further reading

- Dastur A, Beaudenon S, Kelley M, Krug RM, Huibregtse JM (February 2006). "Herc5, an interferon-induced HECT E3 enzyme, is required for conjugation of ISG15 in human cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (7): 4334–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M512830200. PMID 16407192.

- Bektas N, Noetzel E, Veeck J, Press MF, Kristiansen G, Naami A, et al. (2008). "The ubiquitin-like molecule interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15) is a potential prognostic marker in human breast cancer". Breast Cancer Research. 10 (4): R58. doi:10.1186/bcr2117. PMC 2575531. PMID 18627608.

- Andersen JB, Hassel BA (December 2006). "The interferon regulated ubiquitin-like protein, ISG15, in tumorigenesis: friend or foe?". Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 17 (6): 411–21. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.10.001. PMID 17097911.

- Clauss IM, Wathelet MG, Szpirer J, Content J, Islam MQ, Levan G, et al. (1990). "Chromosomal localization of two human genes inducible by interferons, double-stranded RNA, and viruses". Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 53 (2–3): 166–8. doi:10.1159/000132920. PMID 1695131.

- Feltham N, Hillman M, Cordova B, Fahey D, Larsen B, Blomstrom D, Knight E (October 1989). "A 15-kD interferon-induced protein and its 17-kD precursor: expression in Escherichia coli, purification, and characterization". Journal of Interferon Research. 9 (5): 493–507. doi:10.1089/jir.1989.9.493. PMID 2477469.

- Knight E, Fahey D, Cordova B, Hillman M, Kutny R, Reich N, Blomstrom D (April 1988). "A 15-kDa interferon-induced protein is derived by COOH-terminal processing of a 17-kDa precursor". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 263 (10): 4520–2. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)68812-X. PMID 3350799.

- Lowe J, McDermott H, Loeb K, Landon M, Haas AL, Mayer RJ (October 1995). "Immunohistochemical localization of ubiquitin cross-reactive protein in human tissues". The Journal of Pathology. 177 (2): 163–9. doi:10.1002/path.1711770210. PMID 7490683. S2CID 10420781.

- Loeb KR, Haas AL (December 1994). "Conjugates of ubiquitin cross-reactive protein distribute in a cytoskeletal pattern". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 14 (12): 8408–19. doi:10.1128/MCB.14.12.8408. PMC 359380. PMID 7526157.

- Narasimhan J, Potter JL, Haas AL (January 1996). "Conjugation of the 15-kDa interferon-induced ubiquitin homolog is distinct from that of ubiquitin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (1): 324–30. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.1.324. PMID 8550581.

- D'Cunha J, Ramanujam S, Wagner RJ, Witt PL, Knight E, Borden EC (November 1996). "In vitro and in vivo secretion of human ISG15, an IFN-induced immunomodulatory cytokine". Journal of Immunology. 157 (9): 4100–8. PMID 8892645.

- Smith JK, Siddiqui AA, Krishnaswamy GA, Dykes R, Berk SL, Magee M, et al. (August 1999). "Oral use of interferon-alpha stimulates ISG-15 transcription and production by human buccal epithelial cells". Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 19 (8): 923–8. doi:10.1089/107999099313460. PMID 10476939.

- Bebington C, Doherty FJ, Fleming SD (October 1999). "Ubiquitin cross-reactive protein gene expression is increased in decidualized endometrial stromal cells at the initiation of pregnancy". Molecular Human Reproduction. 5 (10): 966–72. doi:10.1093/molehr/5.10.966. PMID 10508226.

- Nyman TA, Matikainen S, Sareneva T, Julkunen I, Kalkkinen N (July 2000). "Proteome analysis reveals ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes to be a new family of interferon-alpha-regulated genes". European Journal of Biochemistry. 267 (13): 4011–9. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01433.x. PMID 10866800.

- Yuan W, Krug RM (February 2001). "Influenza B virus NS1 protein inhibits conjugation of the interferon (IFN)-induced ubiquitin-like ISG15 protein". The EMBO Journal. 20 (3): 362–71. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.3.362. PMC 133459. PMID 11157743.

- Meraro D, Gleit-Kielmanowicz M, Hauser H, Levi BZ (June 2002). "IFN-stimulated gene 15 is synergistically activated through interactions between the myelocyte/lymphocyte-specific transcription factors, PU.1, IFN regulatory factor-8/IFN consensus sequence binding protein, and IFN regulatory factor-4: characterization of a new subtype of IFN-stimulated response element". Journal of Immunology. 168 (12): 6224–31. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6224. PMID 12055236.

- Padovan E, Terracciano L, Certa U, Jacobs B, Reschner A, Bolli M, et al. (June 2002). "Interferon stimulated gene 15 constitutively produced by melanoma cells induces e-cadherin expression on human dendritic cells". Cancer Research. 62 (12): 3453–8. PMID 12067988.