FUNCINPEC

The National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful and Cooperative Cambodia,[lower-alpha 1] commonly referred to as FUNCINPEC,[lower-alpha 2] is a royalist political party in Cambodia. Founded in 1981 by Norodom Sihanouk, it began as a resistance movement against the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) government. In 1982, it formed a resistance pact with the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK), together with the Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF) and the Khmer Rouge. It became a political party in 1992.

National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful and Cooperative Cambodia រណសិរ្សបង្រួបបង្រួមជាតិដើម្បីកម្ពុជាឯករាជ្យ អព្យាក្រិត សន្តិភាព និងសហប្រតិបត្តិការ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | FUNCINPEC |

| President | Norodom Chakravuth |

| Vice President | Norodom Rattana Devi[1] |

| Secretary-General | Pich Sochetha |

| Founder | Norodom Sihanouk |

| Founded | 21 March 1981 |

| Preceded by | Sangkum |

| Headquarters | National Road 6A, Phum Kdey Chas, Sangkat Chroy Changvar, Khan Chroy Changvar, Phnom Penh, Cambodia |

| Membership (2019) | 500,000[2] |

| Ideology | Royalism (Norodom) Conservatism Classical liberalism |

| Political position | Centre-right |

| International affiliation | Centrist Democrat International |

| Colors | Yellow |

| Anthem | "ជយោ! គណបក្សហ៊្វុនស៊ិនប៉ិច" ("Victory! FUNCINPEC Party") |

| Senate | 2 / 62 |

| National Assembly | 5 / 125 |

| Commune chiefs | 0 / 1,652 |

| Commune councillors | 19 / 11,622 |

| Local government[3] | 33 / 4,114 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| funcinpecparty.info (archived) | |

FUNCINPEC was one of the signatories of the 1991 Paris Peace Accords, which paved the way for the formation of the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC). The party participated in the 1993 general elections organised by UNTAC. It won the elections, and formed a coalition government with the Cambodian People's Party (CPP), with which it jointly headed. Norodom Ranariddh, Sihanouk's son who had succeeded him as the party president, became First Prime Minister while Hun Sen, who was from the CPP, became Second Prime Minister.

In July 1997, violent clashes occurred between factional forces separately allied to FUNCINPEC and the CPP, leading to Ranariddh's ouster from his position as First Prime Minister. Ranariddh subsequently returned from exile in March 1998 and led the party to the 1998 general elections, which was won by CPP with FUNCINPEC as the first runner-up. Subsequently, FUNCINPEC joined CPP again, this time as a junior partner in a coalition government. Ranariddh was appointed as the President of the National Assembly, a post which he held until 2006 when he was ousted from FUNCINPEC by the party's former secretary-general Nhek Bun Chhay. At the same time, FUNCINPEC continued to see its share of voters and seats in the national assembly drop over the general elections of 2003, 2008 and 2013, with the party failing to win a single seat in the National Assembly at the 2013 general elections. In January 2015, Ranariddh returned to FUNCINPEC, and was re-appointed as the party's president. The current acting president is Norodom Ranariddh's son, Prince Norodom Chakravuth.[4]

Name

FUNCINPEC is a French acronym for Front uni national pour un Cambodge indépendant, neutre, pacifique, et coopératif, which translates as "National United Front for an Independent, Neutral, Peaceful, and Cooperative Cambodia" in English.[5] However, the party is commonly known by its acronym, used in the form of a word.[6]

History

Formative years

On 21 March 1981, Sihanouk founded FUNCINPEC, a royalist resistance movement, from Pyongyang, North Korea.[7][8] Over the next few months, Sihanouk forged closer ties with the Chinese government as he saw the need of gathering resistance armies sympathetic to FUNCINPEC,[9] such as MOULINAKA (Movement for the National Liberation of Kampuchea).[7] He had resisted earlier attempts between 1979 till 1981 by the Chinese government for him to forge political alliances with the Khmer Rouge, whom he had accused of killing his own family members during the Cambodian genocide.[10] However, he reconsidered his position over allying with the Khmer Rouge, with whom they shared a common goal of ousting the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) government, which was under Vietnam's influence. In September 1981, Sihanouk met with Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF) leader Son Sann and Khmer Rouge leader Khieu Samphan to establish the framework for a coalition government-in-exile.[9] Subsequently, on 22 June 1982, the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK) was formed, and Sihanouk was made its President.[11]

In September 1982, Armee Nationale Sihanoukiste (ANS) was formed by the merger of several pro-FUNCINPEC resistance armies, including MOULINAKA.[12] However, ties between FUNCINPEC with the KPNLF and Khmer Rouge remained tenuous. On the one hand, Son Sann publicly criticised Sihanouk on several occasions, while on the other hand, the Khmer Rouge army periodically attacked the ANS, prompting Sihanouk in threatening to quit as CGDK's president on at least two occasions in June 1983[13] and July 1985.[14] In December 1987, Sihanouk met with the Prime Minister of the PRK government, Hun Sen in France.[15] The following year in July 1988, the first informal meeting was held in Jakarta, Indonesia between the four warring Cambodian factions consisting of FUNCINPEC, Khmer Rouge, KPNLF and the PRK government. The meetings were held with a view to end the Cambodian–Vietnamese War, and two additional meetings were later held which became known as the Jakarta Informal Meetings (JIM).[16]

In August 1989, Sihanouk stepped down as the President of FUNCINPEC and was succeeded by Nhiek Tioulong. At the same time, Ranariddh was made the Secretary-General of the party.[17] In September 1990, the four warring Cambodian factions reached an agreement to form the Supreme National Council (SNC), an organisation designed to oversee Cambodia's sovereign affairs in the United Nations on an interim basis. The SNC consisted of twelve members from the four warring Cambodian factions, with two seats going to FUNCINPEC. Sihanouk negotiated to become the 13th member of the SNC, a proposal which Hun Sen initially rejected,[18] but later acceded after Sihanouk relinquished his FUNCINPEC party membership in July 1991. Sihanouk was elected as the chairman of the SNC,[19] and the SNC seats under FUNCINPEC's quota were filled up by Ranariddh and Sam Rainsy.[20] When the Paris Peace Accords were signed in October 1991, Ranariddh represented the party as its signatory.[21]

1993 elections

Ranariddh was elected as FUNCINPEC's president in February 1992.[22] Subsequently, in August 1992, FUNCINPEC formally registered itself as a political party under the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) administration, and started opening party offices across Cambodia the following month.[23] However, party offices and officials faced harassment and attacks from State of Cambodia (SOC) secret police and military intelligence officials.[24] Between November 1992 and January 1993, 18 FUNCINPEC officials were killed and another 22 officials wounded, prompting Ranariddh to call on UNTAC to intervene and end the violence. UNTAC responded by setting up a special prosecutor's office to investigate cases of political violence,[25] but faced resistance from the SOC police in arresting and prosecuting offenders.[26] Most of the violent attacks occurred in the Kampong Cham and Battambang provinces,[27] whereby the governor in the latter province, Ung Sami was found to have been directly involved in the attacks.[28] When UNTAC allowed election campaigns to start in April 1993, FUNCINPEC held few election rallies due to intimidations from SOC police.[29] They campaigned through low-key methods, such as using pick-up trucks to travel around the country and broadcast political messages as well as sending party workers to visit villages in the countryside.[30]

FUNCINPEC had 400,000 members[31] by the time UNTAC allowed political parties to start election campaigns on 7 April 1993.[32] They campaigned on the party's historical relations with Sihanouk[33] as well as Ranariddh's blood ties to his father. Party supporters wore yellow T-shirts depicting Sihanouk,[34] and made rallying calls that "a vote for FUNCINPEC was a vote for Sihanouk".[35] Sihanouk remained popular with the majority of the Cambodian electorate,[33] and the Cambodian People's Party (CPP), the successor party to the PRK and SOC governments, was aware of such voter sentiments. In their editorials, the CPP emphasised their efforts to bring about Sihanouk's return to the country in 1991, as well as policy parallels between the CPP and the Sangkum, the political organisation which Sihanouk had led in the 1950s and 1960s.[36]

Voting was carried out between 23 and 28 May 1993[37] and FUNCINPEC secured 45.47% of all valid votes cast, which entitled them to take up 58 out of 120 seats in the constituent assembly[38] FUNCINPEC obtained the most seats in Kampong Cham, Kandal and Phnom Penh.[39] The CPP came in second place and secured 38.23% of valid votes,[38] and were unhappy with the outcome of the elections. On 3 June 1993, CPP leaders Chea Sim and Hun Sen met with Sihanouk to propose that he should lead a new interim government, and also demanding power-sharing for the CPP with FUNCINPEC on a fifty-fifty basis. Sihanouk agreed to the CPP's proposal and announced the formation of an interim government that evening.[40] Ranariddh and other FUNCINPEC leaders were not consulted over Sihanouk's proposal, and the announcement caught them by surprise. Ranariddh sent a fax to his father to disapprove of the CPP's proposal,[41] and the United States expressed a similar stance. Sihanouk publicly rescinded his earlier announcement of the interim government's formation the following day.[42]

On 10 June 1993, Chakrapong led a secession movement and threatened to form a breakaway state consisting of seven eastern Cambodian provinces. Chakrapong had by then joined the CPP was supported by the interior minister, General Sin Song[43] and Hun Sen's older brother, Hun Neng. The secession movement pressured Ranariddh to accede to CPP's request for power-sharing, and Hun Sen subsequently persuaded his brother to drop the secession movement.[44] Four days later, the first constituent assembly meeting was held which saw an interim government being formed, with Hun Sen and Ranariddh serving as co-Prime Ministers[45] in a dual Prime Ministership arrangement.[46] There were a total of thirty-three cabinet posts available, while the CPP got sixteen, FUNCINPEC got thirteen and the other coalition partners got the four remaining posts available.[47] When Sihanouk was re-instated as the King of Cambodia on 24 September 1993, he formalised the power-sharing arrangement by appointing Ranariddh as the First Prime Minister and Hun Sen as the Second Prime Minister in the new government.[48]

FUNCINPEC under Ranariddh's co-premiership

The new government shrunk the number of cabinet portfolios to twenty-three, which were equally divided between FUNCINPEC and CPP, each getting eleven ministries under their charge while the BLDP was allocated one cabinet post.[49] The CPP gave away half of all provincial governor posts available to FUNCINPEC, but kept most of the local government posts consisting of district and commune chiefs as well as civil service positions to its party appointees.[50] Ranariddh developed a good working relationship with Hun Sen,[48] which was maintained until March 1996.[51] The UN secretary-general's representative to Cambodia, Benny Widyono noted that while both of them appeared together in public functions, Hun Sen held more political sway as compared to Ranariddh in the government.[52] In October 1994, Ranariddh and Hun Sen sacked Sam Rainsy as FUNCINPEC's finance minister after he repeatedly leaked confidential documents and corruption in a public manner.[53] Rainsy's sacking upset Norodom Sirivudh, the secretary-general for FUNCINPEC and Minister of Foreign Affairs to resign from his ministerial post at the same time.[54] Rainsy continued to criticise the government in his capacity as a Member of Parliament (MP), and Ranariddh introduced a motion to expel Rainsy from the National Assembly and FUNCINPEC.[55]

In October 1995, Sirivudh talked about his desire to assassinate Hun Sen during an interview with So Naro, who was the secretary-general of the Khmer Journalists Association.[56] A few days later Ung Phan, a FUNCINPEC minister who had close ties with Hun Sen,[57] called Sirivudh and accused him of getting involved in receiving kickbacks for printing Cambodian passports. Sirivudh angrily denied the accusations and threatened to kill Hun Sen over the phone. The phone conversation was recorded, and Ung Phan passed the recorded phone conversation to CPP co-minister of the interior Sar Kheng. Hun Sen learnt of the conversation and became enraged at Sirivudh's comments,[56] and pressured Ranariddh and other FUNCINPEC ministers to strip his parliamentary immunity so that he could be arrested. Sirivudh was arrested and briefly placed in detention, but subsequently exiled to France when Sihanouk intervened in the case.[58]

The following January, FUNCINPEC held a closed-door seminar at Sihanoukville, attended by selected party members close to Ranariddh. The attendees expressed concern of CPP's attempts to dominate over FUNCINPEC, and a resolution was adopted to build up the military strength of pro-FUNCINPEC forces within the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF).[59] At the same time, party members had become increasingly resentful at Ranariddh for not getting party posts despite campaigning for the party in the 1993 elections.[60] When the party congress was held on 22 March 1996, Ranariddh criticized the CPP, complaining over a range of issues that ranged from delays in allocating local government posts to FUNCINPEC officials, to the lack of executive authority of FUNCINPEC cabinet ministers vis-a-vis their CPP counterparts. Ranariddh threatened to dissolve the National Assembly and hold elections, should FUNCINPEC's concerns be ignored.[61] Subsequently, the CPP issue an official statement to protest Ranariddh's criticisms.[62]

Hun Sen developed a belligerent attitude towards Ranariddh and FUNCINPEC, calling Ranariddh a "real dog" at a CPP party meeting in June 1996.[63] Several months later in January 1997, Ranariddh led FUNCINPEC to forge a political alliance, the National United Front (NUF), with the Khmer Nation Party, Buddhist Liberal Democratic Party and the Khmer Neutral Party.[64] The CPP condemned NUF's formation, and proceeded to form a rival political coalition consisting of political parties ideologically aligned to the former Khmer Republic.[65] Tensions between FUNCINPEC and the CPP worsened even further[64] when armed clashes between Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF) troops separately aligned to FUNCINPEC and CPP broke out at Battambang Province on 10 February 1997.[66] On that day, troops under the command of the FUNCINPEC provincial deputy governor, Serey Kosal encountered a convoy of 200 pro-CPP troops who were travelling en route to Samlout. After Serey Kosal's troops disarmed the pro-CPP troops, news of the incident spread to nearby areas and fighting soon broke out between troops from both rival factions, leaving at least 21 troops dead.[67][68]

On 14 April 1997, Ung Phan announced that he and twelve other FUNCINPEC MPs had decided to break away from the party. Hun Sen applauded the move, pledging support for any initiative within the party to oust Ranariddh as its president.[65] Subsequently, FUNCINPEC's steering committee quickly moved to woo back the defecting MPs, successfully getting back eight of them.[69] At the same time, they expelled the five remaining MPs who refused to comply, including Ung Phan.[70] Subsequently, on 1 June 1997, the renegade MPs convened a rival party congress dubbed as "FUNCINPEC II",[71] which was attended by 800 people. At the congress, the attendees voted for Toan Chhay, the governor of Siem Reap province, as its new president. At the same time, the attendees accused Ranariddh of gross incompetence, who in return declared the congress as illegal and accused the CPP of interfering in the party's affairs.[65]

Ranariddh's ouster and 1998 elections

On 5 July 1997, RCAF troops separately aligned to CPP and FUNCINPEC fought in Phnom Penh, leading to the latter's defeat the following day.[72] Ranariddh, who had sought refuge in France just two days before the fighting[73] was labelled as a "criminal" and "traitor" by Hun Sen for attempting to "destabilise Cambodia".[72] Subsequently, on 11 July 1997, Loy Sim Chheang, FUNCINPEC's First Vice President of the National Assembly, proposed for another FUNCINPEC MP to replace Ranariddh as the First Prime Minister. Five days later, FUNCINPEC's foreign minister Ung Huot was nominated to take his place.[74] When a National Assembly session was held on 6 August 1997, Ung Huot's appointment was endorsed by 90 MPs, consisting of CPP MPs and FUNCINPEC MPs who have switched allegiances to Hun Sen. At the same time, 29 FUNCINPEC MPs who remained loyal to Ranariddh, boycotted the session.[75]

Shortly after Ung Huot's appointment, Toan Chhay who had proclaimed himself as the president of the FUNCINPEC at a rival congress in June 1997, jockeyed for control over the party leadership with Nady Tan, another FUNCINPEC leader[76] who remained sympathetic to Ranariddh.[77] In October 1997, FUNCINPEC supporters allied to Nady Tan proposed renaming the party to "Sangkum Thmei", hoping to capitalise on the electorate's popularity with the Sangkum Reastr Niyum, Sihanouk's political party when he was in power.[78] While FUNCINPEC did not adopt a new name, the name "Sangkum Thmei" was adopted by a splinter party, led by Loy Sim Chheang who later left FUNCINPEC by February 1998. At the same time, Ung Huot followed suit, and formed another splinter party known as "Reastr Niyum".[79]

In early March 1998, a military court convicted Ranariddh guilty of smuggling weapons and causing instability to the country, sentencing him to a total of 35 years of imprisonment. After ASEAN and the European Union stepped in to condemn the sentences, Ranariddh was pardoned of all charges, allowing him to return to Cambodia on 30 March 1998 to prepare for the general elections scheduled to be held in July 1998,[80] allowing Ranariddh to spearhead FUNCINPEC's election campaign.[81] When campaigning for started in late June 1998,[82] FUNCINPEC focused on pro-monarchial sentiments, improving living standards[83] and anti-Vietnamese rhetoric.[84] However, the party faced numerous obstacles, including loss of access to television and radio channels which had come under CPP's exclusive control following the 1997 clashes,[80] and the difficulties of its supporters in getting to party rallies.[84] When the results were announced on 5 August 1998, FUNCINPEC secured 31.7% of all valid votes, which translates to 43 seats in the National Assembly, lagging behind the CPP which polled 41.4% of the votes and secured 64 seats.[85]

As the CPP required a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly to form a government, it offered FUNCINPEC and the Sam Rainsy Party (SRP), which had come in third place in the elections, to become joint partners of a coalition government.[85] Both Ranariddh and Rainsy, now the leader of his eponymous party refused, and filed complaints against election irregularities to the National Election Committee (NEC). When the NEC turned down their complaints, they organised public protests between 24 August until 7 September 1998, when riot police stepped in to break them up.[86] Subsequently, Sihanouk meditated two meetings in September and November 1998, leading to a political deal being struck between CPP and FUNCINPEC in the second meeting.[87] The deal provided for another coalition government between CPP and FUNCINPEC, with the latter as a junior coalition partner controlling the tourism, justice, education, health, culture and women's-cum-veteran's affairs portfolios.[88] In exchange for FUNCINPEC's support for Hun Sen to become the sole Prime Minister, Ranariddh was made the President of the National Assembly.[89]

Continued co-operation with CPP and Ranariddh's sacking

After becoming the President of the National Assembly, Ranariddh supported the creation of the Cambodian Senate,[90] which was formally established in March 1999. The senate had a total of 61 seats, of which 21 seats were allocated to FUNCINPEC, based on proportional representation vis-a-vis the National Assembly.[87] Over the next few years until 2002, FUNCINPEC maintained cordial ties with the CPP,[91] to which Ranariddh described it as an "eternal partner" during FUNCINPEC's party congress in March 2001.[92] Subsequently, in July 2001, Ranariddh welcomed Sirivudh back into the FUNCINPEC and reappointed him as its secretary-general.[91] The following month, FUNCINPEC replaced several cabinet ministers, governors, and deputy governors from its party. As the deputy secretary general of FUNCINPEC, Nhek Bun Chhay saw it, the reshuffles were done to increase the voters' confidence in the party and prepare for the commune council elections and general elections, which were scheduled to take place in 2002 and 2003 respectively.[93]

When the commune elections were held in February 2002, FUNCINPEC performed poorly, winning control over 10 out of a total of 1,621 communes across Cambodia.[94] Subsequently, rifts within the party boiled into the open as Khan Savoeun, a Deputy Commander-in-chief of the RCAF, accused its co-Minister of the Interior, You Hockry of practising nepotism and corruption. At the same time, Hang Dara[91] and Norodom Chakrapong – the latter had returned to FUNCINPEC in March 1999[95] – formed their own splinter parties and took along a large number of FUNCINPEC party members. A year later in July 2003, The general elections were held, and took 20.8% of the votes,[96] which entitled them to 26 seats in the National Assembly.[97] While the CPP won the election, it still lacked the constitutional requirement of having a two-thirds majority on its own in forming a new government without the support of other coalition partners.[96]

Subsequently, in August 2003, Ranariddh and Rainsy joined hands once again, forming a political alliance known as the "Alliance of Democrats". While the AD agreed to the idea of a coalition government between the CPP, FUNCINPEC and Rainsy's SRP, they also called for Hun Sen to step down as Prime Minister,[98] and reforming the NEC, which the AD claimed that it was filled with CPP's appointees.[96] Hun Sen balked at accepting AD's demands, leading to several months of political stalemate. During this time, several party activists from FUNCINPEC and SRP were killed, purportedly by henchmen linked to the CPP. At the same time, several FUNCINPEC officials have obtained loans from CPP-linked businessmen which they had used for financing their own election campaigns. These officials lobbied Ranariddh into accepting the idea of a CPP-FUNCINPEC coalition government so as to secure government positions and repay their loans.[99]

Ranariddh eventually acceded in June 2004, walking out of his political alliance with Rainsy and agreed to the idea of a CPP-FUNCINPEC coalition government with Hun Sen remaining in his position as Prime Minister. At the same time, Hun Sen coaxed Ranariddh into supporting a constitutional amendment known as a "package vote", which required MPs to support legislation and ministerial appointments by an open show of hands. While Ranariddh acquiesced to Hun Sen's demand, the "package vote" amendment was opposed by the SRP, Sihanouk[100] and CPP President Chea Sim. Ranariddh's decision to join hands with the CPP was criticised by many FUNCINPEC leaders such as Mu Sochua, subsequently leading to their resignation from the party.[101] On 2 March 2006, the National Assembly passed a constitutional amendment which required only a simple majority of parliamentarians to support a government, instead of the two-thirds majority that was previously stipulated.[102] After the amendment was passed, Hun Sen abruptly fired Norodom Sirivudh and Nhek Bun Chhay, who were FUNCINPEC's co-minister of interior and co-minister of defense.[103] Ranariddh protested the dismissals, resigning as the President of the National Assembly and left Cambodia for France.[104]

After Ranariddh's departure, FUNCINPEC splintered into two camps – one camp by members loyal to Ranariddh, while another camp consisted of members that were allied to Nhek Bun Chhay, who by now had become the party's secretary-general and closely associated with Hun Sen. Hun Sen started attacking Ranariddh, accusing the latter of eloping[102] with Ouk Phalla, a former Apsara dancer in getting her own friends and family members into government posts.[105] At the same time, party leaders from both rival camps started quarreling publicly, with Serey Kosal, a FUNCINPEC minister seen to be allied to Ranariddh, accusing Nhek Bun Chhay of attempting to topple Ranariddh.[106] When an extraordinary congress was held on 18 October 2006, Ranariddh was dismissed as FUNCINPEC's president, who was in turn replaced by his brother-in-law, Keo Puth Rasmey.[107] Nhek Bun Chhay justified Ranariddh's ouster on the grounds of his deteriorating relations with Hun Sen as well as his practice of spending prolonged periods of time overseas.[108]

Interregnum years

On 9 November 2006, Nhek Bun Chhay filed a lawsuit accusing Ranariddh of pocketing $3.6 million from the sale of its headquarters to the French embassy in 2005.[109] Within days, Ranariddh returned to Cambodia, and announced the formation of the Norodom Ranariddh Party (NRP) which he positioned it as an opposition party vis-a-vis the CPP and FUNCINPEC.[110] In March 2007 Ranariddh, who feared the prospect of imprisonment from the embezzlement suit, left Cambodia. Subsequently, the Phnom Penh Municipal Court ruled in Nhek Bun Chhay's favour, ruling Ranariddh guilty and sentencing the latter to 18 months of imprisonment.[111] In October 2007, FUNCINPEC endorsed Norodom Arunrasmy, the wife of Keo Puth Rasmey, as the party's candidate for the post of Prime Minister in the general elections slated to be held in 2008. At the same time, Nhek Bun Chhay mooted the possibility of getting back Ranariddh into FUNCINPEC, fearing that the party might have lost its popularity following Ranariddh's ouster.[112]

When the general elections were held in July 2008, FUNCINPEC won 2 seats in the National Assembly as most of the party's supporters voted for the CPP, which won the elections and secured 90 seats in the National Assembly. As a result of its losses incurred in the general election,[113] the CPP took over ministerial positions which were formerly held by FUNCINPEC MPs since 2004, although it still allowed Nhek Bun Chhay to remain in his position as Deputy Prime Minister, while 32 senior party members were appointed as secretary-of-state and undersecretary-of-state positions.[114] In the next few months after the elections, the Phnom Penh Post reported that at least 10 percent of its members defected to the CPP, including its former ministers Pou Sothirak[115] and Sun Chhanthol.[116] In February 2009, FUNCINPEC signed an agreement with the NRP to cooperate for the commune council elections that was slated to take place in May 2009.[117] When the elections took place in that month, the FUNCINPEC-NRP alliance only secured less than 0.1% of all votes cast for the provincial, municipal and district-level seats.[118]

Both FUNCINPEC and NRP held tentative discussions on the possibility of a party merger in June 2009[119] and April 2010,[120] with both parties agreeing to an electoral alliance in June 2010 as a first step towards an eventual merger.[121] In December 2010, Ranariddh publicly for FUNCINPEC and NRP to merge, suggesting that the new party borne out of the merger be named "FUNCINPEC 81", with "81" as a reference point to the year which Sihanouk founded FUNCINPEC in 1981. Sihanouk quickly distanced himself from any association with the party, and posted a website on his website iterating his unequivocal support for Hun Sen and the CPP government. In response, Ranariddh pledged that he would similarly support Hun Sen should the party merger be realised. Nhek Bun Chhay balked at Ranariddh's suggestion, saying that the party merger would cause "difficulties" with the party's continued partnership with the CPP,[122] while the party issued an official statement rejecting Ranariddh's proposal.[123]

In April 2011, Nhek Bun Chhay was elected as the party's president, replacing Keo Puth Rasmey who in turn was appointed the party's chairperson.[124] Thirteen months later, Nhek Bun Chhay and Ranariddh signed an agreement to merge NRP into FUNCINPEC, which provided for Ranariddh to become FUNCINPEC's president with Nhek Bun Chhay as his deputy. The agreement was brokered by Hun Sen, who wanted both parties to reunite.[125] However, the merger agreement fell apart, as Nhek Bun Chhay and Ranariddh accused each other of harbouring thoughts of supporting other opposition parties.[126] Subsequently, in March 2013, Nhek Bun Chhay was succeeded by Norodom Arunrasmy as the party's president, who in turn resumed his former role as the party's secretary-general.[127] When general elections were held in July 2013, FUNCINPEC suffered defeat as it lost its remaining two seats which it held in the National Assembly. In turn, Nhek Bun Chhay relinquished his Deputy Prime Minister position and was made a government adviser,[128] although the CPP-led government appointed 28 FUNCINPEC members as undersecretaries of state.[129]

Ranariddh's return

In early January 2015, Ranariddh expressed his intent to return to FUNCINPEC.[130] At the party congress held on 19 January 2015, Ranariddh was reappointed as FUNCINPEC president, succeeding Arunrasmy who was appointed as its first vice-president, while Nhek Bun Chhay was appointed as second vice-president.[131] However, rifts between Nhek Bun Chhay and Ranariddh quickly surfaced as the both of them sparred with each other over the right to use the party stamp[132] and the appointment of Say Hak as the party's secretary general.[133] Ranariddh eventually gained the upper hand, and Say Hak's appointment was reaffirmed at another party congress held in March 2015. He also managed to convince party delegates present at the congress to adopt a new party logo.[134] At the same time, Ranariddh appointed four more vice-presidents to the party's executive committee, namely You Hockry, Por Bun Sreu, Nuth Sokhom and Nhep Bun Chin.[135]

In July 2015, FUNCINPEC announced the formation of the Cambodian Royalist Youth Movement, a youth organisation aimed at garnering electoral support for the party from younger voters.[136] Meanwhile, tension persisted between Nhek Bun Chhay and Ranariddh, which erupted into a public spat, as Ranariddh threatened to expelled Nhek Bun Chhay who in turn, accused the party president of holding a grudge against him.[137] Subsequently, on 3 February 2016, Nhek Bun Chhay announced that he was quitting the party, and went on to form his new party, the Khmer National United Party (KNUP). The KNUP adopted a logo which was similar to a former logo of FUNCINPEC, featuring the Cambodian Independence Monument.[138] The secretary-general, Say Hak accepted Nhek Bun Chhay's resignation, while at the same time challenged KNUP's use of its new logo[139] as he lodged a successful complaint with the interior ministry.[140]

FUNCINPEC declared on 1 June 2017 that it is open to legalizing same-sex marriage.[141] The party came runners-up to the Cambodian People's Party in the 2018 general election but did not win any seats in a vote described by multiple observers as a "formality".[142]

Military

FUNCINPEC had its own military forces, which was first known as the Armee Nationale Sihanoukiste (ANS) when it was formed on 4 September 1982.[12] The ANS was an amalgamation of several armed resistance movements that have pledged alliances with Sihanouk. They consisted of MOULINAKA, Kleang Moeung, Oddar Tus and Khmer Angkor, giving the ANS a combined strength of 7,000 troops.[143] In Tam, a former Prime Minister of the Khmer Republic, was appointed as the Commander-in-chief of the ANS in its founding year. In the initial years of after its formation, the ANS received weapons and equipment from China, as well as medical supplies and combat training for its troops from Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand.[144] At the same time, the ANS regularly faced attacks from the Khmer Rouge forces until 1987, suffering heavy casualties as a result.[145]

In March 1985, Sihanouk appointed one of his sons, Norodom Chakrapong as the deputy chief-of-staff of ANS.[13] The following January, Sihanouk appointed another son, Norodom Ranariddh as the ANS chief-of-staff. Ranariddh was also made the Commander-in-chief of the ANS, replacing In Tam.[146] When the Paris Peace Accords were signed in 1991, the ANS had a total of 17,500 troops under its command,[147] although it was reduced to 14,000 after the UNTAC attempted a demobilisation exercise that lasted between May and September 1992.[148] In 1993, the ANS was amalgamated into the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF), together with the Cambodian People's Armed Forces (CPAF) and KPNLF armed forces, under UNTAC supervision.[47] However, troops from each of the three former armies retained their factional loyalties to their respective former resistance affiliations.[149] The ex-ANS troops came under the command of General Nhek Bun Chhay,[150] who served as the deputy chief of staff for the RCAF between 1993 and 1997.[151]

In the years between 1993 till 1996, the Cambodian defence ministry attempted to integrate the different factions together, but were unsuccessful.[152] In a dossier written by Nhek Bun Chhay around mid-1997, there were 80,800 pro-FUNCINPEC troops, which were divided into 11 battalions across the country. Nhek also express concern of the inferior troop strength of the pro-FUNCINPEC forces, as they were slightly outnumbered compared to 90,000 pro-CPP troops.[153] In November 1996, armed skirmishes occurred between RCAF troops separately aligned to CPP and FUNCINPEC, after a pro-CPP general, Keo Pong accused a pro-FUNCINPEC general, Serey Kosal of attempting to kill him, who in turn accused Keo Pong of recruiting Khmer Rouge defectors into his ranks. More armed skirmishes broke out until February 1997, leaving 14 pro-CPP and 2 pro-FUNCINPEC troops wounded.[154] Subsequently, Ke Kim Yan, the chief-of-staff of the RCAF stepped in to meditate the conflict, and a directive was issued to prohibit movement of troops without the explicit permission of the government.[155] In late March 1997, the two co-defense ministers, Tea Banh of the CPP and Tea Chamrath of FUNCINPEC, together with Ke Kim Yan and Nhek Bun Chhay formed a bipartisan defence committee was formed to prevent the RCAF from getting embroiled into the political conflict between Ranariddh and Hun Sen.[155]

However, even the defence committee was formed, the Cambodian media reported of continued and unusual troop movements[156] positioning themselves in Phnom Penh, and minor skirmishes between troops from both sides occurred sporadically until June 1997.[157] On 4 July 1997, Nhek Bun Chhay signed a military pact with the Khmer Rouge at Anlong Veng,[158] prompting pro-CPP troops to strike their pro-FUNCINPEC counterparts the following day.[72] Violent clashes erupted between pro-CPP and pro-FUNCINPEC forces at FUNCINPEC headquarters, Pochentong Airport and Ranariddh's residence in Phnom Penh.[159] The pro-FUNCINPEC forces, led by Nhek Bun Chhay initially gained an advantage as they were able to control up to half of the city,[160] but were soon overwhelmed and defeated the following day after pro-CPP forces sent in additional troops.[161] Over the next three days, pro-CPP troops arrested and several at least 33 pro-FUNCINPEC senior military officers.[162] Among those who were executed included Ly Seng Hong, deputy chief-of-staff of RCAF; Ho Sok, secretary of state of the Interior Ministry and Chao Sambath, deputy chief of the espionage and military intelligence department of RCAF.[163]

In subsequent days after the clashes, pro-CPP troops continued their military offensives against pro-FUNCINPEC troops in the northwestern parts of Cambodia, which controlled the towns of Sisophon, Banteay Meanchey and Poipet. The pro-FUNCINPEC troops, who were outmatched against their pro-CPP counterparts,[153] retreated to O Smach in Oddar Meanchey Province, where they held out against pro-CPP troops which continued military offensives against them. At O Smach, pro-FUNCINPEC forces met the Khmer Rouge forces led by Khieu Samphan, who proclaimed Nhek Bun Chhay as the chief-of-staff of the resistance forces.[158] Fighting continued between pro-CPP and pro-FUNCINPEC troops until February 1998, when both sides agreed to a ceasefire brokered by the Japanese government.[164] After general elections were held in July 1998, Nhek Bun Chhay called for the 20,000 pro-FUNCINPEC forces to be reintegrated into the RCAF. Subsequently, Nhek Bun Chhay left O Smach, returned to Phnom Penh[165] and was appointed as a senator.[166] Khan Savoeun, a former subordinate of Nhek Bun Chhay, was subsequently appointed as one of the four deputy commander-in-chief of the RCAF in February 1999.[167]

List of party presidents

List of officeholders

| No. | Image | Name (birth-death) |

Term of office |

|---|---|---|---|

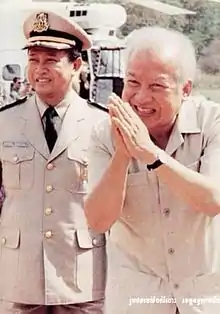

| 1 | .jpg.webp) |

Norodom Sihanouk (1922–2012) |

1981–1989 |

| 2 |  |

Nhiek Tioulong (1908–1996) |

1989–1992 |

| 3 |  |

Norodom Ranariddh (1944–2021) |

1992–2006 |

| 4 |  |

Keo Puth Rasmey (1952–) |

2006–2011 |

| 5 |  |

Nhek Bun Chhay (1956–) |

2011–2013 |

| 6 | .jpg.webp) |

Norodom Arunrasmy (1955–) |

2013–2015 |

| (3) | .jpg.webp) |

Norodom Ranariddh (1944–2021) |

2015–2021[lower-alpha 3] |

| Vacant Norodom Ranariddh died in office in 2021 so his son Norodom Chakravuth who the vice president was appointed as the acting president of FUNCINPEC. | 2021 | ||

| – | Norodom Chakravuth (1970–) |

2021 | |

| 7 | 2021–present | ||

Recent electoral history

General election

| Election | Leader | Votes | Seats | Position | Government | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ± | # | ± | ||||

| 1993[168] | Norodom Ranariddh | 1,824,188 | 45.5 | New | 58 / 120 |

New | FUNCINPEC–CPP–BLDP | |

| 1998[169] | 1,554,405 | 31.7 | 43 / 122 |

CPP–FUNCINPEC | ||||

| 2003[170] | 1,072,313 | 20.7 | 26 / 123 |

CPP–FUNCINPEC | ||||

| 2008[171] | Keo Puth Rasmey | 303,764 | 5.0 | 2 / 123 |

CPP–FUNCINPEC | |||

| 2013[172] | Norodom Arunrasmy | 242,413 | 3.7 | 0 / 123 |

Extra-parliamentary | |||

| 2018[173] | Norodom Ranariddh | 374,510 | 5.9 | 0 / 125 |

Extra-parliamentary | |||

| 2023[174] | Norodom Chakravuth | 716,443 | 9.2 | 5 / 125 |

CPP | |||

Communal elections

| Election | Leader | Votes | Chiefs | Councillors | Position | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | ± | # | ± | # | ± | |||

| 2002[175] | Norodom Ranariddh | 955,200 | 22.0 | New | 10 / 1,621 |

New | 2,194 / 11,261 |

New | |

| 2007[176] | Keo Puth Rasmey | 277,545 | 5.4 | 2 / 1,621 |

274 / 11,353 |

||||

| 2012[177] | Nhek Bun Chhay | 222,663 | 3.8 | 1 / 1,633 |

151 / 11,459 |

||||

| 2017[178] | Norodom Ranariddh | 132,319 | 1.9 | 0 / 1,646 |

28 / 11,572 |

||||

| 2022 | Norodom Chakravuth | 91,798 | 1.3 | 0 / 1,652 |

19 / 11,622 |

||||

See also

- Category:FUNCINPEC politicians

References

- "Funcinpec president appoints princess as vice-president". Khmer Times. 13 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "លោកណុប សុធារិទ្ធិ ៖ សមាជិកហ្វ៊ុនស៊ិនប៉ិចភាគច្រើនមិនព្រមរួបរួម" (in Khmer). The Phnom Penh Post. 24 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- Khorn, Savi (11 June 2019). "Ministry: Councillors to be appointed by next Monday". The Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- "Ranariddh appoints his son leader of Funcinpec amid medical treatment".

- Widyono (2008), p. xii

- Michael Hayes (24 March 2006). "The rise and demise of Funcinpec". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 235

- David M. Ayres (2000). Anatomy of a Crisis: Education, Development, and the State in Cambodia, 1953–1998. University of Hawaii Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-8248-2238-5.

- Jeldres (2005), p. 236

- Jeldres (2005), pp. 218–9

- Jeldres (2005), p. 238

- Mehta (2001), p. 69

- Mehta (2001), p. 73

- Mehta (2001), p. 74

- Widyono (2008), p. 33

- Widyono (2008), p. 34

- Mehta (2001), p. 82

- Findlay (1995), p. 8

- Findlay (1995), p. 9

- Findlay (1995), p. 58

- Secretariat of the United Nations (1991), p. 300

- Widyono (2008), p. 154

- Widyono (2008), p. 116

- Hughes (1996), p. 33

- Hughes (1996), p. 50

- Heder & Ledgerwood (1995), pp. 125, 127

- Heder & Ledgerwood (1995), p. 120

- Hughes (1996), p. 51

- Heder & Ledgerwood (1995), p. 198

- Heder & Ledgerwood (1995), p. 199

- Mehta (2001), p. 93

- Mehta (2001), p. 91

- Heder & Ledgerwood (1995), p. 63

- Mehta (2001), p. 92

- Widyono (2008), p. 118

- Heder & Ledgerwood (1995), p. 193

- Findlay (1995), p. 82

- Findlay (1995), p. 84

- Mehta (2001), p. 123

- Widyono (2008), p. 124

- Mehta (2001), p. 99

- Widyono (2008), p. 125

- Widyono (2008), p. 128

- Mehta (2001), p. 102

- Widyono (2008), p. 129

- Mehta (2001), p. 104

- Widyono (2008), p. 130

- Widyono (2008), p. 131

- Widyono (2008), p. 144

- Widyono (2008), p. 145

- Widyono (2008), p. 165

- Widyono (2008), p. 166

- Widyono (2008), pp. 178–9

- Mehta (2001), p. 142

- Widyono (2008), p. 180

- Widyono (2008), p. 183

- Widyono (2008), p. 188

- Widyono (2008), pp. 184–5

- Widyono (2008), p. 214

- Widyono (2008), p. 216

- Widyono (2008), p. 215

- Widyono (2008), p. 217

- Jason Barber (26 July 1996). "Hun Sen takes hard line at party summit". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Peou (2000), p. 295

- Widyono (2008), p. 240

- Widyono (2008), p. 237

- Tricia Fitzgerald; Sok Pov (21 February 1997). "Factional fighting jolts the northwest". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Brad Adams (28 July 1996). "Cambodia: July 1997: Shock and Aftermath". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- Peou (2000), p. 343

- Peou (2000), p. 344

- Summers (2003), p. 235

- Peou (2000), p. 298

- Mehta (2001), p. 110

- Peou (2000), p. 345

- Widyono (2008), p. 260

- Nick Lenaghan (29 August 1997). "Funcinpec chiefs eye up top positions". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Peou (2000), p. 370

- Claudi Arizzi; Huw Watkin (24 October 1997). "Funcinpec members moot new 'Sangkum'". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Jason Barber (13 February 1998). "The aim of the game". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Summers (2003), p. 237

- Mehta (2001), p. 128

- Peou (2000), p. 316

- Peou (2000), p. 317

- Samreth Sopha; Elizabeth Moorthy (17 July 1998). "Funcinpec relies on royalty, anti-VN rhetoric". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- Peou (2000), p. 318

- Peou (2000), p. 319

- Summers (2003), p. 238

- Mehta (2001), p. 131

- Widyono (2008), p. 268

- Beth Moorthy; Samreth Sopha (19 February 1999). "Prince eager to push for Senate creation". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Summers (2003), p. 239

- Mehta (2001), p. 179

- Thet Sambath; Matt Reed (11 September 2001). "Funcinpec Reshuffle Part of Sirivudh's Strategy". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Van Roeun (9 March 2002). "Commune Election Figures Made Final By NEC". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Mehta (2001), p. 161

- Strangio (2014), p. 99

- Yun Samean (1 September 2003). "CPP Wins 73 Seats in Official Election Returns". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Yun Samean; Porter Barron (18 August 2003). "Prince Repeats Call for a 3-Party Coalition". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Strangio (2014), p. 100

- Strangio (2014), p. 101

- Strangio (2014), p. 102

- Strangio (2014), p. 113

- Widoyono (2008), p. 277

- Widoyono (2008), p. 278

- Yun Samean (3 May 2006). "Over 40 F'pec Officials Removed From Posts". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Vong Sokheng (16 June 2006). "Split widens as Funcinpec hierarchs trade verbal blows". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Vong Sokheng (20 October 2006). "Funcinpec dismisses Ranariddh". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Yun Samean; James Welsh (19 October 2006). "Prince Ousted As President Of Funcinpec". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- Yun Samean (10 November 2006). "Suit Filed on Sale of F'pec Headquarters". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2015.

- Vong Sokheng (17 November 2006). "Ranariddh: 'Now, I am the opposition party". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Strangio (2014), p. 114

- Vong Sokheng (18 October 2007). "RF'PEC wants Ranariddh back in the fold". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Strangio (2014), p. 115

- Cheang Sokha (14 August 2008). "Funcinpec to lose govt posts in poll aftermath". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Vong Sokheng; Neth Pheaktra (14 August 2008). "Flood of Funcinpec defectors continue". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Vong Sokheng (2 February 2009). "Funcinpec defections continue unabated, as six more jump ship". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Meas Sokchea (3 February 2009). "Royalists unite for elections". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Post Staff (19 May 2009). "CPP win 75pc of council vote: NEC". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Meas Sokchea (9 June 2009). "Two royalist parties to remain independent, for the time being". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Tep Nimol (6 April 2010). "Royalist parties to merge this month: official". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Meas Sokchea (8 June 2010). "Royalists form new alliance". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Meas Sokchea; Vong Sokheng (13 December 2010). "Prince floats coalition deal". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Meas Sokchea (2 January 2011). "Funcinpec still opposed to royalist merger". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Meas Sokchea (4 April 2011). "Funcinpec taps Bun Chhay". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Vong Sokheng; Bridget Di Certo (25 May 2012). "Funcinpec, NRP set to merge". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Meas Sokchea (19 June 2012). "Royalist merger shaken again". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Fu Peng (23 March 2013). "Daughter of late King Sihanouk officially leads royalist party to contest in July's polls". Xinhua. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- May Titthara (16 October 2013). "CPP keeps Funcinpec close, despite no seats". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Meas Sokchea (5 November 2013). "Funcinpec enters fray". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Chhay Channyda; Pech Sotheary (2 January 2015). "Going back to his roots". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- Mech Dara; Alex Willemyns (20 January 2015). "Ranariddh Named Funcinpec President—Again". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 4 August 2015. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- HUL REAKSMEY AND ALEX WILLEMYNS (23 February 2015). "Funcinpec Factions War Over Who Can Issue Official Letters". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- MECH DARA (25 February 2015). "Funcinpec Party's Feud Over Secretary-General Post Continues". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Kang Sothear (13 March 2015). "Prince Ranariddh Wins Funcinpec Power Struggle". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 13 August 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Meas Sokchea (13 March 2015). "Funcinpec goes for the gold". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- Hul Reaksmey (27 July 2015). "Royalist Party Forms 'Youth Movement'". VOA Cambodia. Archived from the original on 15 December 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Ros Chanveasna (31 January 2016). "Back as Funcinpec President, Ranariddh Looks to Oust an Old Enemy". Khmer Times. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- KHUON NARIM (4 February 2016). "Ex-Military Commander Leaves Prince, Launches New Party". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Vong Sokheng (5 February 2016). "Bun Chhay can leave, logo stays: Funcinpec". Phnom Penh Post. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- KHUON NARIM (13 February 2016). "With New Logo, Nhek Bun Chhay Presses Ahead With Party Plans". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- Vichea, Pang (1 June 2017). "Parties open to gay marriage". phnompenhpost.com. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "Hun Sen's CPP wins all parliamentary seats in Cambodia election". Al Jazeera. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Im (2005), p. 89

- Mehta (2001), p. 68

- Mehta (2001), p. 75

- Mehta (2001), p. 184

- Widyono (2008), p. 76

- Widyono (2008), p. 78

- Widyono (2008), p. 147

- Peou (2000), p. 294

- Sané (1998), p. 5

- Peou (2000), p. 347

- Peou (2000), p. 351

- Peou (2000), p. 348

- Peou (2000), p. 349

- Widyono (2008), p. 244

- Widyono (2008), p. 253

- Peou (2000), p. 352

- Widyono (2008), p. 255

- Widyono (2008), p. 257

- Widyono (2008), p. 258

- Peou (2000), p. 304

- Peou (2000), p. 305

- Stew Magnuson; Kimsan Chantara (28 February 1998). "Gov't, Resistance Agree to Cease-fire". The Cambodia Daily. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- Peou (2000), p. 355

- Bou Saroeun; Peter Sainsbury (1 October 1999). "Nhek Bun Chhay mystified by attack on wife and home". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- Michael Hayes; Bou Saroeun (5 February 1999). "CPP in control of RCAF, major reforms promised". Phnom Penh Post. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "Election 1993".

- "Election 1998".

- "Election 2003".

- "Election 2008".

- "Election 2013".

- "Election 2018". Archived from the original on 2018-07-31. Retrieved 2018-07-31.

- "NEC announces preliminary vote count for national election". Khmer Times. 27 July 2023. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- "Report on the Commune Council Elections – 3 February 2002" (PDF). comfrel.org. Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL). March 2002. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Final Assessment and Report on 2007 Commune Council Elections" (PDF). comfrel.org. Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL). 1 April 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Final Assessment and Report on 2012 Commune Council Elections" (PDF). comfrel.org. Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL). October 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Final Assessment and Report on 2017 Commune Council Elections" (PDF). comfrel.org. Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL). October 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Election 2006".

- "Election 2012".

- "Election 2018".

Bibliography

Books

- Hughes, Caroline (1996). UNTAC in Cambodia: The Impact on Human Rights. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9813055235.

- Findlay, Trevor (1995). Cambodia – The Legacy and Lessons of UNTAC–SIPRI Research Report No. 9 (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Solna, Sweden: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198291868. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-08-05.

- Im, François (2005). La question cambodgienne dans les relations internationales de 1979 à 1993. France: Atelier national de reproduction des thèses. ISBN 2284049060.

- Jeldres, Julio A (2005). Volume 1–Shadows Over Angkor: Memoirs of His Majesty King Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia. Phnom Penh Cambodia: Monument Books. ISBN 974926486X.

- Heder, Stepher R.; Ledgerwood, Julie (1995). Propaganda, Politics and Violence in Cambodia: Democratic Transition Under United Nations Peace-Keeping. United States of America: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765631741.

- Mehta, Harish C.; Julie B. (2013). Strongman: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen: The Extraordinary Life of Hun Sen. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. ISBN 978-9814484602.

- Mehta, Harish C. (2001). Warrior Prince: Norodom Ranariddh, Son of King Sihanouk of Cambodia. Singapore: Graham Brash. ISBN 9812180869.

- Peou, Sorpong (2000). Intervention and Change in Cambodia: Towards Democracy?. National University of Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9812300422.

- Strangio, Sebastian (2014). Hun Sen's Cambodia. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300210149.

- Summers, Laura (2003). The Far East and Australasia 2003. New York: Psychology Press. pp. 227–243. ISBN 1857431332.

- Widyono, Benny (2008). Dancing in Shadows: Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge, and the United Nations in Cambodia. Lanham, Maryland, United States of America: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742555532.

Reports

- Sané, Pierre (23 April 1998). "Kingdom of Cambodia – Human rights at stake" (PDF). Amnesty International. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- Secretariat of the United Nations (23 October 1991). "Treaties and international agreements registered or filed and recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations–No. 28613. Multilateral" (PDF). Treaty Series – Treaties and International Agreements Registered or Filed and Recorded with the Secretariat of the United Nations. United Nations. 1663 (28609–28619). Retrieved 8 July 2015.