Feta

Feta (Greek: φέτα, féta) is a Greek brined white cheese made from sheep's milk or from a mixture of sheep and goat's milk. It is soft, with small or no holes, a compact touch, few cuts, and no skin. Crumbly with a slightly grainy texture, it is formed into large blocks and aged in brine. Its flavor is tangy and salty, ranging from mild to sharp. Feta is used as a table cheese, in salads such as Greek salad, and in pastries, notably the phyllo-based Greek dishes spanakopita "spinach pie" and tyropita "cheese pie". It is often served with olive oil or olives, and sprinkled with aromatic herbs such as oregano. It can also be served cooked (often grilled), as part of a sandwich, in omelettes, and many other dishes.

| Feta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Country of origin | Greece |

| Region | Mainland Greece and Lesbos Prefecture |

| Source of milk | Sheep (≥70%) and goat per PDO; similar cheeses may contain cow or buffalo milk |

| Pasteurized | Depends on variety |

| Texture | Depends on variety |

| Aging time | Min. 3 months |

| Certification | PDO, 2002 |

Since 2002, feta has been a protected designation of origin in the European Union. EU legislation and similar legislation in 25 other countries[1] limits the name feta to cheeses produced in the traditional way in mainland Greece and Lesbos Prefecture,[2] which are made from sheep's milk, or from a mixture of sheep's and up to 30% of goat's milk from the same area.[3]

Similar white brined cheeses are made traditionally in the Balkans, around the Black Sea, in West Asia, and more recently elsewhere. Outside the EU, the name feta is often used generically for these cheeses.[4]

Generic term and production outside Greece

For many consumers, the word feta is a generic term for a white, crumbly cheese aged in brine. Production of the cheese first began in the Eastern Mediterranean and around the Black Sea. Over time, production expanded to countries including Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States, often partly or wholly of cow's milk, and they are (or were) sometimes also called feta.[4][5] In the United States, most cheese sold under the name feta is American and made from cows' milk.[6]

Geographical Indication

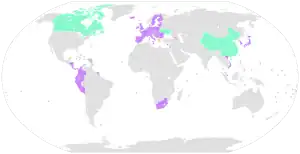

Since 2002, feta has been a Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) product within the European Union. According to the relevant EU legislation (applicable within the EU and Northern Ireland), as well as similar UK legislation only those cheeses produced in a traditional way in particular areas of Greece, which are made from sheep's milk, or from a mixture of sheep's and up to 30% of goat's milk from the same area, can be called feta. Also in several other countries the term feta has since been protected. An overview is shown in the table below.

| Country/Territory | Start of protection | Comments/Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| European Union | 15 October 2002 | PDO, also valid in Northern Ireland |

| Armenia | 26 January 2018 | Also protected as Ֆետա |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 18 February 2016 | |

| Canada | 21 September 2017 | Use of Feta including the terms "kind", "type", "style", "imitation" etc. is allowed, as well as use by producers using the term before 18 October 2013. |

| China | 1 March 2021 | Also protected as 菲达奶酪. Until 1 March 2029 limited use of the term is allowed for similar products. |

| Colombia | ||

| Costa Rica | ||

| El Salvador | ||

| Ecuador | ||

| Georgia | 1 April 2012 | Also protected as ფეტა. |

| Guatemala | ||

| Honduras | ||

| Iceland | 1 May 2018 | |

| Japan | 1 February 2019 | Also protected as フェタ. |

| Kosovo | 1 April 2016 | |

| Liechtenstein | 27 July 2007 | |

| Moldova | 1 April 2013 | |

| Montenegro | 1 January 2008 | |

| Nicaragua | ||

| Panama | ||

| Peru | ||

| Serbia | 1 February 2010 | |

| Singapore | 29 June 2019 | |

| South Africa | 1 November 2016 | |

| South Korea | 14 May 2011 | Also protected as 페따. |

| Switzerland | 1 December 2014 | |

| Ukraine | 31 December 2015 | Also protected as Фета. As of 31 December 2022, limited use of the term is no longer allowed for similar products |

| United Kingdom | 31 December 2020 | Continuation of EU PDO, valid in England, Scotland and Wales |

| Vietnam | 1 August 2020 |

Description

The EU PDO for feta requires a maximum moisture of 56%, a minimum fat content in dry matter of 43%, and a pH that usually ranges from 4.4 to 4.6.[7] Production of the EU PDO feta is traditionally categorized into firm and soft varieties. The firm variety is tangier and considered higher in quality. The soft variety is almost soft enough to be spreadable, mostly used in pies and sold at a cheaper price. Slicing feta produces some amount of trímma, "crumble", which is also used for pies (not being sellable, trímma is usually given away for free upon request).

High-quality feta should have a creamy texture when sampled, and aromas of ewe's milk, butter, and yoghurt. In the mouth it is tangy, slightly salty, and mildly sour, with a spicy finish that recalls pepper and ginger, as well as a hint of sweetness. According to the specification of the Geographical Indication, the biodiversity of the land coupled with the special breeds of sheep and goats used for milk is what gives feta cheese a specific aroma and flavor.[2]

Production

Traditionally (and legally within the EU and other territories where it is protected), feta is produced using only whole sheep's milk, or a blend of sheep's and goat's milk (with a maximum of 30% goat's milk).[8] The milk may be pasteurized or not, but most producers now use pasteurized milk. If pasteurized milk is used, a starter culture of micro-organisms is added to replace those naturally present in raw milk which are killed in pasteurization. These organisms are required for acidity and flavour development.

When the pasteurized milk has cooled to approximately 35 °C (95 °F),[9][10] rennet is added and the casein is left to coagulate. The compacted curds are then chopped up and placed in a special mould or a cloth bag that allows the whey to drain.[11][12] After several hours, the curd is firm enough to cut up and salt;[9] salinity will eventually reach approximately 3%,[10] when the salted curds are placed (depending on the producer and the area of Greece) in metal vessels or wooden barrels and allowed to infuse for several days.[9][10][12]

After the dry-salting of the cheese is complete, aging or maturation in brine (a 7% salt in water solution) takes several weeks at room temperature and a further minimum of 2 months in a refrigerated high-humidity environment—as before, either in wooden barrels or metal vessels,[10][12] depending on the producer (the more traditional barrel aging is said to impart a unique flavour). The containers are then shipped to supermarkets where the cheese is cut and sold directly from the container; alternatively blocks of standardized weight are packaged in sealed plastic cups with some brine.

Feta dries relatively quickly even when refrigerated; if stored for longer than a week, it should be kept in brine or lightly salted milk.

History

They make a great many cheeses; it is a pity they are so salty. I saw great warehouses full of them, some in which the brine, or salmoria as we would say was two feet deep, and the large cheeses were floating in it. Those in charge told me that the cheeses could not be preserved in any other way, being so rich. They do not know how to make butter. They sell a great quantity to the ships that call there: it was astonishing to see the number of cheeses taken on board our own galley.

Pietro Casola, 15th-century Italian traveller to Crete[13]

Cheese made from sheep and goat milk has been common in the Eastern Mediterranean since ancient times.[14][15] In Bronze Age Canaan, cheese was perhaps among the salted foods shipped by sea in ceramic jars and so rennet-coagulated white cheeses similar to feta may have been shipped in brine, but there is no direct evidence for this.[16] In Greece, the earliest documented reference to cheese production dates back to the 8th century BC and the technology used to make cheese from sheep-goat milk is similar to the technology used by Greek shepherds today to produce feta.[17][18] In the Odyssey, Homer describes how Polyphemus makes cheese and dry-stores it in wicker racks,[19][20] though he says nothing about brining,[21] resulting perhaps, according to Paul S. Kindstedt, in a rinded cheese similar to modern pecorino and caprino rather than feta.[22] On the other hand, E. M. Antifantakis and G. Moatsou state that Polyphemus' cheese was "undoubtedly the ancestor of modern Feta".[23] Origins aside, cheese produced from sheep-goat milk was a common food in ancient Greece and an integral component of later Greek gastronomy.[17][18][23]

The first unambiguous documentation of preserving cheese in brine appears in Cato the Elder's De Agri Cultura (2nd century BCE) though the practice was surely much older.[24] It is also described in the 10th-century Geoponica.[24] Feta cheese, specifically, is recorded by Psellos in the 11th century under the name prósphatos (Greek πρόσφατος 'recent, fresh'), and was produced by Cretans.[25] In the late 15th century, an Italian visitor to Candia, Pietro Casola, describes the marketing of feta, as well as its storage in brine.[13] Feta cheese, along with milk and sheep meat, is the principal source of income for shepherds in northwestern Greece.[26]

The Greek word feta (φέτα) comes from the Italian fetta 'slice', which in turn is derived from the Latin offa 'morsel, piece'.[27][28] The word feta became widespread as a name for the cheese only in the 19th century, probably referring to the cheese being cut to pack it in barrels.[15]

Effect of Certification as a Geographical Indication

Prior to Greece's pursuit of a PDO for its feta, there was long-standing production out of Greece in three member states: Germany, Denmark and France, and in certain countries (e.g. Denmark) feta was perceived as a generic term, while it was perceived as a designation of origin in others (e.g. Greece), with the centre of production and consumption taking place in Greece.[29] Greece first requested the registration of Feta as a designation of origin in the EU in 1994, which was approved in 1996 by commission regulation (EC) No 1107/96[30] The decision was appealed to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) by Denmark, France and Germany, which annulled the decision as the Commission did not evaluate sufficiently whether or not Feta had become a generic term.[31] After that decision, the European Commission reevaluated registering Feta as a PDO, taking into account production in other EU countries and re-registered feta as a PDO in Commission Regulation (EC) No 1829/2002. This decision was appealed again at CJEU by Denmark and Germany. In 2005, the CJEU upheld the Commission Regulation. It indicated that indeed the term was generic in some EU countries and that production also took place outside Greece, but that on the other hand the geographical region in Greece was well defined and that even non-Greek producers often appealed to the status of Feta as a Greek product through the choice of packaging.[29]

Although the island of Cephalonia also traditionally produces feta, the island was left out of the definition of the protected designation of origin. While this does not play a role for consumers in Greece, dairies lose out in sales abroad because they do not produce real “Feta” and have to accept price reductions.[32]

The European Commission gave other nations five years to find a new name for their feta cheese or stop production.[3] Because of the decision by the European Union, Danish dairy company Arla Foods changed the name of its white cheese products to Apetina, which is also the name of an Arla food brand established in 1991.[33] When needed to describe an imitation feta, names such as "salad cheese" and "Greek-style cheese" are used.

The EU included Feta in several Associations Agreements, Free Trade Agreements and agreements on the recognition of Geographical Indications, which led to the expansion of protection of the term Feta. Exporters from the EU to foreign markets outside the territories covered by these agreements, are not subject to the European Commission rules. As such, the non-Greek EU cheese sold abroad is often labeled as feta.

In 2013, an agreement was reached with Canada (CETA) in which Canadian feta manufacturers retained their rights to continue producing feta while new entrants to the market would label the product "feta-style/type cheese".[34][35][36][37] In other markets such as the United States, Australia, New Zealand and elsewhere, full generic usage of the term "feta" continues.

Some cheeses from the EU were renamed. In 2007, the British cheese Yorkshire Feta was renamed to Fine Fettle Yorkshire.[38]

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,103 kJ (264 kcal) |

4 g | |

21 g | |

14 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A | 422 IU |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 70% 0.84 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 19% 0.97 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 32% 0.42 mg |

| Vitamin B12 | 71% 1.7 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 49% 493 mg |

| Sodium | 74% 1116 mg |

| Zinc | 31% 2.9 mg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Like many dairy products, feta has significant amounts of calcium and phosphorus; however, feta is higher in water and thus lower in fat and calories than aged cheeses like Parmigiano-Reggiano or Cheddar.[39] The cheese may contain beneficial probiotics.[40]

Feta, as a sheep dairy product, contains up to 1.9% conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), which is about 0.8% of its fat content.[41]

Feta cheese is very high in salt, at over 400 mg sodium per 100 calories.[42]

Similar cheeses

Similar cheeses can be found in other countries, such as:

- Albania (djathë i bardhë or djathë i Gjirokastrës)

- Armenia (Չանախ chanakh - cheese made in a chan, a type of crock)

- Azerbaijan (ağ pendir, lit. 'white cheese')

- Bosnia (Travnički/Vlašićki sir, lit. "cheese from Vlašić/Travnik")

- Bulgaria (бяло сирене, bjalo sirene, lit. "white cheese")

- Canada (feta style cheese, or simply feta for those companies producing the cheese prior to October 2013)

- Cyprus (χαλίτζια, halitzia)

- Czech Republic (balkánský sýr, lit. "Balkan cheese")

- Egypt (domiati)

- Finland (salaattijuusto, "salad cheese")

- Georgia (ყველი, kveli, lit. "cheese")

- Germany (Schafskäse, "sheep cheese")

- Hungary (juhturo)

- Iran (Lighvan cheese; پنیر لیقوان panīr-e līghvān)

- Israel (gvinat rosh hanikra, lit. "Rosh Hanikra cheese", sometimes falsely called abroad 'Israeli feta'.)

- Italy (casu 'e fitta Sardinia)

- Lebanon (gibneh bulgharieh, lit. "Bulgarian cheese")

- North Macedonia (сирење, sirenje)

- Palestine and Jordan (Nabulsi cheese; جبنة نابلسية, and Akkawi; عكاوي)

- Romania (brânză telemea)

- Russia (брынза, brynza)

- Serbia (сир, sir as a common name; сирење, sirenje in South, including Kosovo Serb; and brinza in north and east Serbia within Slovak and Aromanian populations)

- Slovakia (bryndza and Balkánsky syr, lit. "Balkan cheese")

- Spain (Queso de Burgos, lit. "Burgos cheese")

- Sudan (gibna beyda, lit. "white cheese")

- Turkey (beyaz peynir, lit. "white cheese")

- Ukraine (бринза, brynza)

- United Kingdom ("salad cheese")

See also

- List of ancient dishes and foods

- List of cheeses – List of cheeses by place of origin

Citations

- "oriGIn Worldwide GIs Compilation". ORIGIN-GI. Archived from the original on 1 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- "Φέτα / Feta". GI View - European Union. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- Gooch, Ellen (Spring–Summer 2006). "Truth, Lies, and Feta: The Cheese that Launched a (Trade) War". Epikouria: Fine Foods and Drinks of Greece. Triaina Publishing. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009.

- Pappas, Gregory (2015). "Feta Cheese at the Heart of Growing US-EU Trade Tensions". The Pappas Post. Elite CafeMedia Lifestyle.

- "Defining a Name's Origin: The Case of Feta". www.wipo.int. 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "What's in a name? U.S, EU battle over "feta" in trade talks". Reuters. 24 July 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- "Presenting the Feta Cheese P.D.O. – Feta's Description". Fetamania. CheeseNet: Promoting Greek PDO Cheese. 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- European Union (15 October 2002). Feta: Livestock Farming. European Commission – Agriculture and Rural Development: Door. p. 18.

- Harbutt 2006.

- "Feta Production". Fetamania. CheeseNet: Promoting Greek PDO Cheese. 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Barthélemy & Sperat-Czar 2004.

- "Greek Cheese". Odysea. Odysea Limited. 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Dalby 1996, p. 190.

- Dalby 1996, pp. 23, 43.

- Adams 2016, p. 271.

- Kindstedt 2012, pp. 48–50.

- Polychroniadou-Alichanidou 2004, p. 283.

- Bintsis & Alichanidis 2018, p. 180.

- Odyssey 9:219-249

- Hatziminaoglou & Boyazoglou 2004, p. 126: "Homer in his famous ancient Greek book, the Odyssey, describes the use of dairy goats during the Mycenean times (about 1200 B.C.), when the Cyclops Polyphemus in his cave sat down to milk his goats and sheep, then put aside half of the milk to be curdled in wicker baskets with the previous day’s whey".

- Razionale 2016, p. 360.

- Kindstedt 2012, pp. 74–76.

- Antifantakis & Moatsou 2006, p. 43.

- Kindstedt 2012, p. 50.

- Michael Psellos. "Poem on Medicine", 1:209; Dalby 1996, p. 190.

- Öncel, Fatma (2020). "Transhumants and Rural Change in Northern Greece Throughout the Nineteenth Century" (PDF). International Review of Social History (published 2021). 66 (1): 49. doi:10.1017/S0020859020000371. ISSN 0020-8590. S2CID 225563374.

Every summer, from time immemorial, shepherds have brought their flocks to the high pastures of the Pindos Mountains in the northwest corner of Greece. […] Milk, feta cheese, and the meat from the lambs are the shepherds' principal source of income.

- Harper, David (2001–2020). "feta (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Babiniotis 1998.

- "Joined Cases C-465/02 and C-466/02 Feta". CJEU. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- "Commission Regulation (EC) No 1107/96 of 12 June 1996 on the registration of geographical indications and designations of origin under the procedure laid down in Article 17 of Council Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92". European Commission.

- "In Joined Cases C-289/96, C-293/96 and C-299/96 Feta". CJEU. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- item/%CF%84%CF%85%CF%81%CE%BF%CE%BA%CE%BF%CE%BC%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%AC-%CE%BA%CE% B5%CF%86%CE%B1%CE%BB%CE%BF%CE%BD%CE%B9%CE%AC%CF%82/

- "Arla Apetina". Arla. Arla Foods. 2013. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- Emmott, Robin (5 May 2015). "Greece wants changes to EU-Canada trade deal to protect "feta" name". Reuters. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Official Journal of the European Union 2017, p. 141.

- General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union (www.consilium.europa.eu/en/); Greek Delegation (www.mfa.gr/brussels/en/) (30 April 2015). "Protection of the Geographical Indication of Feta Cheese in the Context of the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) — Request from the Greek Delegation" (PDF). Foreign Affairs/Trade Council Session of 2015-05-07 (WTO 100 Note [Annex is Presentation of Greek Request]). Brussels. p. 3. ST 8508 2015 INIT. Retrieved 18 January 2019..

- Christides, Giorgos (13 December 2013). "Feta Cheese Row Sours EU-Canada Trade Deal". BBC. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

But new Canadian brands of 'feta' will have to call their cheese 'feta-style' or 'imitation feta' and cannot evoke Greece on the label, such as using Greek lettering or an image of ancient Greek columns.

- "Feta-ccompli for big cheese name". bbc.co.uk. 30 April 2007.

- Θερμόπουλος, Μιχάλης (12 July 2020). "Φέτα: Τι προσφέρει και τι κινδύνους κρύβει – Διατροφικά στοιχεία". iatropedia.

- Cutcliffe, Tom (15 March 2018). "My big fat Greek functional food - probiotic feta could become a big cheese". Nutrain Ingredients. Retrieved 30 April 2020 – via Food Microbiology.

- Prandini, Sigolo & Piva 2011, pp. 55–61.

- "Cheese, feta Nutrition Facts & Calories". NutritionData: Know What You Eat. Condé Nast. 2018.

General and cited references

- Adams, Alexis Marie (2016). "feta". In Donnelly, Catherine W. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Cheese. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 269–271. ISBN 978-0199330881.

- Antifantakis, E. M.; Moatsou, G. (2006). "2 Feta and Other Balkan Cheeses". In Tamime, Adnan (ed.). Brined Cheeses. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 43–76. ISBN 9781405124607.

- Babiniotis, George D. (1998). Λεξικό της νέας ελληνικής γλώσσας με σχόλια για τη σωστή χρήση των λέξεων Λεξικό της Νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας (in Greek). Athens: Kentro Leksikologias. ISBN 9789608619005.

- Barthélemy, Roland; Sperat-Czar, Arnaud (2004). Cheeses of the World. London: Hachette Illustrated. ISBN 978-1-84-430115-7.

- Bintsis, Thomas; Alichanidis, Efstathios (2018). "Cheeses from Greece". In Papademas, Photis; Bintsis, Thomas (eds.). Global Cheesemaking Technology: Cheese Quality and Characteristics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 180–181. ISBN 9781119046158.

- Dalby, Andrew (1996). Siren Feasts: A History of Food and Gastronomy in Greece. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781134969852.

- Kindstedt, Paul S. (2012). Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and Its Place in Western Civilization. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing. ISBN 978-1603584128.

- Harbutt, Juliet (2006). The World Encyclopedia of Cheese. London: Hermes House. ISBN 9781843099604.

- Hatziminaoglou, Y.; Boyazoglou, J. (2004). "The goat in ancient civilisations: from the Fertile Crescent to the Aegean Sea". Small Ruminant Research. 51 (2): 123–129. doi:10.1016/j.smallrumres.2003.08.006.

- "Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)". Official Journal of the European Union. 2017.

- Polychroniadou-Alichanidou, Anna (2004). "13: Traditional Greek Feta". In Hui, Y.H.; Meunier-Goddik, Lisbeth; Josephsen, Jytte; Nip, Wai-Kit; Stanfield, Peggy S. (eds.). Handbook of Food and Beverage Fermentation Technology. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. pp. 283–299. ISBN 9780824751227.

- Prandini, Aldo; Sigolo, Samantha; Piva, Gianfranco (2011). "A comparative study of fatty acid composition and CLA concentration in commercial cheeses". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 24 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2010.04.004.

- Razionale, Vince (2016). "Homer". In Donnelly, Catherine W. (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Cheese. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0199330881.

Further reading

- Petridou, Evangelia (2001). Milk Ties: A Commodity Chain Approach to Greek Culture (PDF). London: University College London.