Fetus

A fetus or foetus (/ˈfiːtəs/; PL: fetuses, feti, foetuses, or foeti) is the unborn offspring that develops from an animal embryo.[1] Following embryonic development the fetal stage of development takes place. In human prenatal development, fetal development begins from the ninth week after fertilization (or eleventh week gestational age) and continues until birth. Prenatal development is a continuum, with no clear defining feature distinguishing an embryo from a fetus. However, a fetus is characterized by the presence of all the major body organs, though they will not yet be fully developed and functional and some not yet situated in their final anatomical location.

| Part of a series on |

| Human growth and development |

|---|

|

| Stages |

| Biological milestones |

| Development and psychology |

Etymology

The word fetus (plural fetuses or feti) is related to the Latin fētus ("offspring", "bringing forth", "hatching of young")[2][3][4] and the Greek "φυτώ" to plant. The word "fetus" was used by Ovid in Metamorphoses, book 1, line 104.[5]

The predominant British, Irish, and Commonwealth spelling is foetus, which has been in use since at least 1594. The spelling with -oe- arose in Late Latin, in which the distinction between the vowel sounds -oe- and -e- had been lost. This spelling is the most common in most Commonwealth nations, except in the medical literature, where the fetus is used. The more classical spelling fetus is used in Canada and the United States. In addition, fetus is now the standard English spelling throughout the world in medical journals.[6] The spelling faetus was also used historically.[7]

Development in humans

Weeks 9 to 16 (2 to 3.6 months)

In humans, the fetal stage starts nine weeks after fertilization.[8] At the start of the fetal stage, the fetus is typically about 30 millimetres (1+1⁄4 in) in length from crown-rump, and weighs about 8 grams.[8] The head makes up nearly half of the size of the fetus.[9] Breathing-like movements of the fetus are necessary for the stimulation of lung development, rather than for obtaining oxygen.[10] The heart, hands, feet, brain, and other organs are present, but are only at the beginning of development and have minimal operation.[11][12]

At this point in development, uncontrolled movements and twitches occur as muscles, the brain, and pathways begin to develop.[13]

Weeks 17 to 25 (3.6 to 6.6 months)

A woman pregnant for the first time (nulliparous) typically feels fetal movements at about 21 weeks, whereas a woman who has given birth before will typically feel movements by 20 weeks.[14] By the end of the fifth month, the fetus is about 20 cm (8 in) long.

Weeks 26 to 38 (6.6 to 8.6 months)

The amount of body fat rapidly increases. Lungs are not fully mature. Neural connections between the sensory cortex and thalamus develop as early as 24 weeks of gestational age, but the first evidence of their function does not occur until around 30 weeks. Bones are fully developed but are still soft and pliable. Iron, calcium, and phosphorus become more abundant. Fingernails reach the end of the fingertips. The lanugo, or fine hair, begins to disappear until it is gone except on the upper arms and shoulders. Small breast buds are present in both sexes. Head hair becomes coarse and thicker. Birth is imminent and occurs around the 38th week after fertilization. The fetus is considered full-term between weeks 37 and 40 when it is sufficiently developed for life outside the uterus.[15][16] It may be 48 to 53 cm (19 to 21 in) in length when born. Control of movement is limited at birth, and purposeful voluntary movements continue to develop until puberty.[17][18]

Variation in growth

There is much variation in the growth of the human fetus. When the fetal size is less than expected, the condition is known as intrauterine growth restriction also called fetal growth restriction; factors affecting fetal growth can be maternal, placental, or fetal.[19]

Maternal factors include maternal weight, body mass index, nutritional state, emotional stress, toxin exposure (including tobacco, alcohol, heroin, and other drugs which can also harm the fetus in other ways), and uterine blood flow.

Placental factors include size, microstructure (densities and architecture), umbilical blood flow, transporters and binding proteins, nutrient utilization, and nutrient production.

Fetal factors include the fetal genome, nutrient production, and hormone output. Also, female fetuses tend to weigh less than males, at full term.[19]

Fetal growth is often classified as follows: small for gestational age (SGA), appropriate for gestational age (AGA), and large for gestational age (LGA).[20] SGA can result in low birth weight, although premature birth can also result in low birth weight. Low birth weight increases the risk for perinatal mortality (death shortly after birth), asphyxia, hypothermia, polycythemia, hypocalcemia, immune dysfunction, neurologic abnormalities, and other long-term health problems. SGA may be associated with growth delay, or it may instead be associated with absolute stunting of growth.

Viability

Fetal viability refers to a point in fetal development at which the fetus may survive outside the womb. The lower limit of viability is approximately 5+3⁄4 months gestational age and is usually later.[21]

There is no sharp limit of development, age, or weight at which a fetus automatically becomes viable.[22] According to data from 2003 to 2005, survival rates are 20–35% for babies born at 23 weeks of gestation (5+3⁄4 months); 50–70% at 24–25 weeks (6 – 6+1⁄4 months); and >90% at 26–27 weeks (6+1⁄2 – 6+3⁄4 months) and over.[23] It is rare for a baby weighing less than 500 g (1 lb 2 oz) to survive.[22]

When such premature babies are born, the main causes of mortality are that the respiratory system and the central nervous system are not completely differentiated. If given expert postnatal care, some preterm babies weighing less than 500 g (1 lb 2 oz) may survive, and are referred to as extremely low birth weight or immature infants.[22]

Preterm birth is the most common cause of infant mortality, causing almost 30 percent of neonatal deaths.[23] At an occurrence rate of 5% to 18% of all deliveries,[24] it is also more common than postmature birth, which occurs in 3% to 12% of pregnancies.[25]

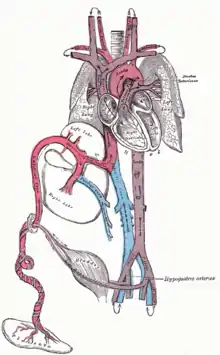

Circulatory system

Before birth

The heart and blood vessels of the circulatory system form relatively early during embryonic development, but continue to grow and develop in complexity in the growing fetus. A functional circulatory system is a biological necessity since mammalian tissues can not grow more than a few cell layers thick without an active blood supply. The prenatal circulation of blood is different from postnatal circulation, mainly because the lungs are not in use. The fetus obtains oxygen and nutrients from the mother through the placenta and the umbilical cord.[26]

Blood from the placenta is carried to the fetus by the umbilical vein. About half of this enters the fetal ductus venosus and is carried to the inferior vena cava, while the other half enters the liver proper from the inferior border of the liver. The branch of the umbilical vein that supplies the right lobe of the liver first joins with the portal vein. The blood then moves to the right atrium of the heart. In the fetus, there is an opening between the right and left atrium (the foramen ovale), and most of the blood flows from the right into the left atrium, thus bypassing pulmonary circulation. The majority of blood flow is into the left ventricle from where it is pumped through the aorta into the body. Some of the blood moves from the aorta through the internal iliac arteries to the umbilical arteries and re-enters the placenta, where carbon dioxide and other waste products from the fetus are taken up and enter the mother's circulation.[26]

Some of the blood from the right atrium does not enter the left atrium, but enters the right ventricle and is pumped into the pulmonary artery. In the fetus, there is a special connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta, called the ductus arteriosus, which directs most of this blood away from the lungs (which are not being used for respiration at this point as the fetus is suspended in amniotic fluid).[26]

Fetus at 4+1⁄4 months

Fetus at 4+1⁄4 months Fetus at 5 months

Fetus at 5 months

Postnatal development

With the first breath after birth, the system changes suddenly. Pulmonary resistance is reduced dramatically, prompting more blood to move into the pulmonary arteries from the right atrium and ventricle of the heart and less to flow through the foramen ovale into the left atrium. The blood from the lungs travels through the pulmonary veins to the left atrium, producing an increase in pressure that pushes the septum primum against the septum secundum, closing the foramen ovale and completing the separation of the newborn's circulatory system into the standard left and right sides. Thereafter, the foramen ovale is known as the fossa ovalis.

The ductus arteriosus normally closes within one or two days of birth, leaving the ligamentum arteriosum, while the umbilical vein and ductus venosus usually closes within two to five days after birth, leaving, respectively, the liver's ligamentum teres and ligamentum venosus.

Immune system

The placenta functions as a maternal-fetal barrier against the transmission of microbes. When this is insufficient, mother-to-child transmission of infectious diseases can occur.

Maternal IgG antibodies cross the placenta, giving the fetus passive immunity against those diseases for which the mother has antibodies. This transfer of antibodies in humans begins as early as the fifth month (gestational age) and certainly by the sixth month.[27]

Developmental problems

A developing fetus is highly susceptible to anomalies in its growth and metabolism, increasing the risk of birth defects. One area of concern is the lifestyle choices made during pregnancy.[28] Diet is especially important in the early stages of development. Studies show that supplementation of the person's diet with folic acid reduces the risk of spina bifida and other neural tube defects. Another dietary concern is whether breakfast is eaten. Skipping breakfast could lead to extended periods of lower than normal nutrients in the maternal blood, leading to a higher risk of prematurity, or birth defects.

Alcohol consumption may increase the risk of the development of fetal alcohol syndrome, a condition leading to intellectual disability in some infants.[29] Smoking during pregnancy may also lead to miscarriages and low birth weight (2,500 grams (5 pounds 8 ounces). Low birth weight is a concern for medical providers due to the tendency of these infants, described as "premature by weight", to have a higher risk of secondary medical problems.

X-rays are known to have possible adverse effects on the development of the fetus, and the risks need to be weighed against the benefits.[30][31]

Congenital disorders are acquired before birth. Infants with certain congenital heart defects can survive only as long as the ductus remains open: in such cases the closure of the ductus can be delayed by the administration of prostaglandins to permit sufficient time for the surgical correction of the anomalies. Conversely, in cases of patent ductus arteriosus, where the ductus does not properly close, drugs that inhibit prostaglandin synthesis can be used to encourage its closure, so that surgery can be avoided.

Other heart birth defects include ventricular septal defect, pulmonary atresia, and tetralogy of Fallot.

An abdominal pregnancy can result in the death of the fetus and where this is rarely not resolved it can lead to its formation into a lithopedion.

Fetal pain

The existence and implications of fetal pain are debated politically and academically. According to the conclusions of a review published in 2005, "Evidence regarding the capacity for fetal pain is limited but indicates that fetal perception of pain is unlikely before the third trimester."[32][33] However, developmental neurobiologists argue that the establishment of thalamocortical connections (at about 6+1⁄2 months) is an essential event with regard to fetal perception of pain.[34] Nevertheless, the perception of pain involves sensory, emotional and cognitive factors and it is "impossible to know" when pain is experienced, even if it is known when thalamocortical connections are established.[34] Some authors argue that fetal pain is possible from the second half of pregnancy. Evidence suggests that the perception of pain in the fetus occurs well before late gestation.[35][36]

Whether a fetus has the ability to feel pain and suffering is part of the abortion debate.[37][38] In the United States, for example, anti-abortion advocates have proposed legislation that would require providers of abortions to inform pregnant women that their fetuses may feel pain during the procedure and that would require each person to accept or decline anesthesia for the fetus.[39]

Legal and social issues

Abortion of a human pregnancy is legal and/or tolerated in most countries, although with gestational time limits that normally prohibit late-term abortions.[40]

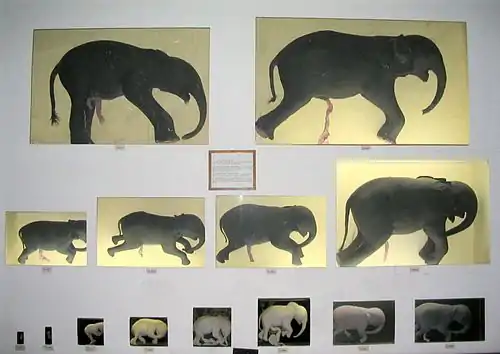

Other animals

A fetus is a stage in the prenatal development of viviparous organisms. This stage lies between embryogenesis and birth.[1] Many vertebrates have fetal stages, ranging from most mammals to many fish. In addition, some invertebrates bear live young, including some species of onychophora[41] and many arthropods.

The fetuses of most mammals are situated similarly to the human fetus within their mothers.[42] However, the anatomy of the area surrounding a fetus is different in litter-bearing animals compared to humans: each fetus of a litter-bearing animal is surrounded by placental tissue and is lodged along one of two long uteri instead of the single uterus found in a human female.

Development at birth varies considerably among animals, and even among mammals. Altricial species are relatively helpless at birth and require considerable parental care and protection. In contrast, precocial animals are born with open eyes, have hair or down, have large brains, and are immediately mobile and somewhat able to flee from, or defend themselves against, predators. Primates are precocial at birth, with the exception of humans.[43]

The duration of gestation in placental mammals varies from 18 days in jumping mice to 23 months in elephants.[44] Generally speaking, fetuses of larger land mammals require longer gestation periods.[44]

The benefits of a fetal stage means that young are more developed when they are born. Therefore, they may need less parental care and may be better able to fend for themselves. However, carrying fetuses exerts costs on the mother, who must take on extra food to fuel the growth of her offspring, and whose mobility and comfort may be affected (especially toward the end of the fetal stage).

In some instances, the presence of a fetal stage may allow organisms to time the birth of their offspring to a favorable season.[41]

See also

References

- Ghosh, Shampa; Raghunath, Manchala; Sinha, Jitendra Kumar (2017), "Fetus", Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior, Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–5, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_62-1, ISBN 9783319478296

- O.E.D.2nd Ed.2005

- Harper, Douglas. (2001). Online Etymology Dictionary Archived 2013-04-20 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- "Charlton T. Lewis, An Elementary Latin Dictionary, fētus". Archived from the original on 2017-01-04. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- Miller, Frank Justus (1951) [1916]. Ovid Metamorphoses. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Harvard University Press and William Heinemann Ltd. p. 8. ark:/13960/t9n30qx2z.

- New Oxford Dictionary of English.

- American Dictionary of the English Language, Noah Webster, 1828.

- Klossner, N. Jayne, Introductory Maternity Nursing (2005): "The fetal stage is from the beginning of the 9th week after fertilization and continues until birth"

- "Fetal development: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-10-27.

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention Archived 2011-06-07 at the Wayback Machine (2006), page 317. Retrieved 2008-03-12

- The Columbia Encyclopedia Archived 2007-10-12 at the Wayback Machine (Sixth Edition). Retrieved 2007-03-05.

- Greenfield, Marjorie. "Dr. Spock.com Archived 2007-01-22 at the Wayback Machine". Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- Prechtl, Heinz. "Prenatal and Early Postnatal Development of Human Motor Behavior" in Handbook of brain and behaviour in human development, Kalverboer and Gramsbergen eds., pp. 415-418 (2001 Kluwer Academic Publishers): "The first movements to occur are sideward bendings of the head. ... At 9-10 weeks postmestrual age complex and generalized movements occur. These are the so-called general movements (Prechtl et al., 1979) and the startles. Both include the whole body, but the general movements are slower and have a complex sequence of involved body parts, while the startle is a quick, phasic movement of all limbs and trunk and neck."

- Levene, Malcolm et al. Essentials of Neonatal Medicine Archived 2023-04-08 at the Wayback Machine (Blackwell 2000), p. 8. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- "You and your baby at 37 weeks pregnant". NHS.UK. 8 December 2020. Archived from the original on 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- "Giving Birth Before Your Due Date: Do All 40 Weeks Matter?". Parents. Archived from the original on 2022-11-02. Retrieved 2022-11-01.

- Stanley, Fiona et al. "Cerebral Palsies: Epidemiology and Causal Pathways", page 48 (2000 Cambridge University Press): "Motor competence at birth is limited in the human neonate. The voluntary control of movement develops and matures during a prolonged period up to puberty...."

- Becher, Julie-Claire. "Insights into Early Fetal Development". Archived from the original on 2013-06-01., Behind the Medical Headlines (Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow October 2004)

- Holden, Chris and MacDonald, Anita. Nutrition and Child Health Archived 2020-07-31 at the Wayback Machine (Elsevier 2000). Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- Queenan, John. Management of High-Risk Pregnancy Archived 2023-04-24 at the Wayback Machine (Blackwell 1999). Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- Halamek, Louis. "Prenatal Consultation at the Limits of Viability Archived 2009-06-08 at the Wayback Machine", NeoReviews, Vol.4 No.6 (2003): "most neonatologists would agree that survival of infants younger than approximately 22 to 23 weeks' estimated gestational age [i.e. 20 to 21 weeks' estimated fertilization age] is universally dismal and that resuscitative efforts should not be undertaken when a neonate is born at this point in pregnancy."

- Moore, Keith and Persaud, T. The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology, p. 103 (Saunders 2003).

- March of Dimes - Neonatal Death Archived 2014-10-24 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved September 2, 2009.

- World Health Organization (November 2014). "Preterm birth Fact sheet N°363". who.int. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- Buck, Germaine M.; Platt, Robert W. (2011). Reproductive and perinatal epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780199857746. Archived from the original on 2016-08-15.

- Whitaker, Kent (2001). Comprehensive Perinatal and Pediatric Respiratory Care. Delmar. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- Page 202 of Pillitteri, Adele (2009). Maternal and Child Health Nursing: Care of the Childbearing and Childrearing Family. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-58255-999-5.

- Dalby, JT (1978). "Environmental effects on prenatal development". Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 3 (3): 105–109. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/3.3.105.

- Streissguth, Ann Pytkowicz (1997). Fetal alcohol syndrome: a guide for families and communities. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Pub. ISBN 978-1-55766-283-5.

- O'Reilly, Deirdre. "Fetal development Archived 2011-10-27 at the Wayback Machine". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia (2007-10-19). Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- De Santis, M; Cesari, E; Nobili, E; Straface, G; Cavaliere, AF; Caruso, A (September 2007). "Radiation effects on development". Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews. 81 (3): 177–82. doi:10.1002/bdrc.20099. PMID 17963274.

- Lee, Susan; Ralston, HJ; Drey, EA; Partridge, JC; Rosen, MA (August 24–31, 2005). "Fetal Pain A Systematic Multidisciplinary Review of the Evidence". Journal of the American Medical Association. 294 (8): 947–54. doi:10.1001/jama.294.8.947. PMID 16118385. Two authors of the study published in JAMA did not report their abortion-related activities, which pro-life groups called a conflict of interest; the editor of JAMA responded that JAMA probably would have mentioned those activities if they had been disclosed, but still would have published the study. See Denise Grady, "Study Authors Didn't Report Abortion Ties" Archived 2009-04-25 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times (2005-08-26).

- "Study: Fetus feels no pain until third trimester" Archived 2019-10-28 at the Wayback Machine NBC News

- Johnson, Martin and Everitt, Barry. Essential reproduction (Blackwell 2000): "The multidimensionality of pain perception, involving sensory, emotional, and cognitive factors may in itself be the basis of conscious, painful experience, but it will remain difficult to attribute this to a fetus at any particular developmental age." Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- Glover V. The fetus may feel pain from 20 weeks. Conscience. 2004-2005 Winter;25(3):35-7

- "Fetal pain?". www.iasp-pain.org. Archived from the original on 2013-07-01.

- White, R. Frank. " [[New research has discovered that unborn babies can feel pain. "The neural pathways are present for pain to be experienced quite early by unborn babies," explains Steven Calvin, M.D., perinatologist, chair of the Program in Human Rights Medicine, University of Minnesota, where he teaches obstetrics." ]http://www.asahq.org/Newsletters/2001/10_01/white.htm Are We Overlooking Fetal Pain and Suffering During Abortion?] Archived 2016-07-19 at the Wayback Machine", American Society of Anesthesiologists Newsletter (October 2001). Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- David, Barry & and Goldberg, Barth. "Recovering Damages for Fetal Pain and Suffering Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine", Illinois Bar Journal (December 2002). Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- Weisman, Jonathan. "House to Consider Abortion Anesthesia Bill Archived 2008-10-28 at the Wayback Machine", Washington Post 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- Anika Rahman, Laura Katzive and Stanley K. Henshaw. "A Global Review of Laws on Induced Abortion, 1985-1997 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine", International Family Planning Perspectives Volume 24, Number 2 (June 1998).

- Campiglia, Sylvia S.; Walker, Muriel H. (1995). "Developing embryo and cyclic changes in the uterus of Peripatus (Macroperipatus) acacioi (Onychophora, Peripatidae)". Journal of Morphology. 224 (2): 179–198. doi:10.1002/jmor.1052240207. PMID 29865325. S2CID 46928727.

- ZFIN, Pharyngula Period (24-48 h) Archived 2007-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. Modified from: Kimmel et al., 1995. Developmental Dynamics 203:253-310. Downloaded 5 March 2007.

- Lewin, Roger. Human Evolution Archived 2023-04-07 at the Wayback Machine, page 78 (Blackwell 2004).

- Sumich, James and Dudley, Gordon. Laboratory and Field Investigations in Marine Life, page 320 (Jones & Bartlett 2008).

External links

- Prenatal Image Gallery Index at the Endowment for Human Development website, featuring numerous motion pictures of human fetal movement.

- In the Womb (National Geographic video).

- Fetal development: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia