Field coil

A field coil is an electromagnet used to generate a magnetic field in an electro-magnetic machine, typically a rotating electrical machine such as a motor or generator. It consists of a coil of wire through which a current flows.

In a rotating machine, the field coils are wound on an iron magnetic core which guides the magnetic field lines. The magnetic core is in two parts; a stator which is stationary, and a rotor, which rotates within it. The magnetic field lines pass in a continuous loop or magnetic circuit from the stator through the rotor and back through the stator again. The field coils may be on the stator or on the rotor.

The magnetic path is characterized by poles, locations at equal angles around the rotor at which the magnetic field lines pass from stator to rotor or vice versa. The stator (and rotor) are classified by the number of poles they have. Most arrangements use one field coil per pole. Some older or simpler arrangements use a single field coil with a pole at each end.

Although field coils are most commonly found in rotating machines, they are also used, although not always with the same terminology, in many other electromagnetic machines. These include simple electromagnets through to complex lab instruments such as mass spectrometers and NMR machines. Field coils were once widely used in loudspeakers before the general availability of lightweight permanent magnets.

Fixed and rotating fields

Most[note 1] DC field coils generate a constant, static field. Most three-phase AC field coils are used to generate a rotating field as part of an electric motor. Single-phase AC motors may follow either of these patterns: small motors are usually universal motors, like the brushed DC motor with a commutator, but run from AC. Larger AC motors are generally induction motors, whether these are three-phase or single-phase.

Stators and rotors

Many[note 1] rotary electrical machines require current to be conveyed to (or extracted from) a moving rotor, usually by means of sliding contacts: a commutator or slip rings. These contacts are often the most complex and least reliable part of such a machine, and may also limit the maximum current the machine can handle. For this reason, when machines must use two sets of windings, the windings carrying the least current are usually placed on the rotor and those with the highest current on the stator.

The field coils can be mounted on either the rotor or the stator, depending on whichever method is the most cost-effective for the device design.

In a brushed DC motor the field is static but the armature current must be commutated, so as to continually rotate. This is done by supplying the armature windings on the rotor through a commutator, a combination of rotating slip ring and switches. AC induction motors also use field coils on the stator, the current on the rotor being supplied by induction in a squirrel cage.

For generators, the field current is smaller than the output current.[note 2] Accordingly, the field is mounted on the rotor and supplied through slip rings. The output current is taken from the stator, avoiding the need for high-current sliprings. In DC generators, which are now generally obsolete in favour of AC generators with rectifiers, the need for commutation meant that brushgear and commutators could still be required. For the high-current, low-voltage generators used in electroplating, this could require particularly large and complex brushgear.

Bipolar and multipolar fields

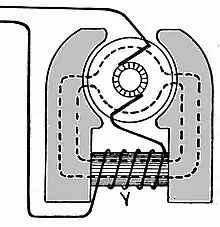

Salient field bipolar generator |

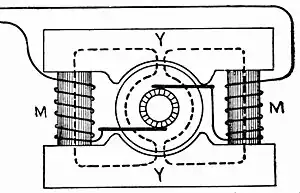

Consequent field bipolar generator |

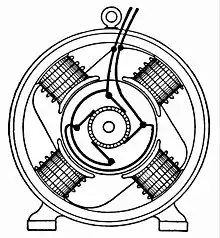

Consequent field, four-pole, shunt-wound DC generator |

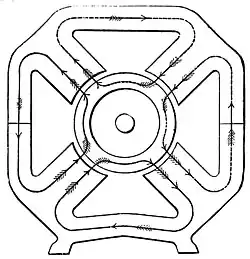

Field lines of a four-pole stator passing through a Gramme ring or drum rotor. |

In the early years of generator development, the stator field went through an evolutionary improvement from a single bipolar field to a later multipole design.

Bipolar generators were universal prior to 1890 but in the years following it was replaced by the multipolar field magnets. Bipolar generators were then only made in very small sizes.[1]

The stepping stone between these two major types was the consequent-pole bipolar generator, with two field coils arranged in a ring around the stator.

This change was needed because higher voltages transmit power more efficiently over small wires. To increase the output voltage, a DC generator must be spun faster, but beyond a certain speed this is impractical for very large power transmission generators.

By increasing the number of pole faces surrounding the Gramme ring, the ring can be made to cut across more magnetic lines of force in one revolution than a basic two-pole generator. Consequently, a four-pole generator could output twice the voltage of a two-pole generator, a six-pole generator could output three times the voltage of a two-pole, and so forth. This allows output voltage to increase without also increasing the rotational rate.

In a multipolar generator, the armature and field magnets are surrounded by a circular frame or "ring yoke" to which the field magnets are attached. This has the advantages of strength, simplicity, symmetrical appearance, and minimum magnetic leakage, since the pole pieces have the least possible surface and the path of the magnetic flux is shorter than in a two-pole design.[1]

Winding materials

Coils are typically wound with enamelled copper wire, sometimes termed magnet wire. The winding material must have a low resistance, to reduce the power consumed by the field coil, but more importantly to reduce the waste heat produced by resistive heating. Excess heat in the windings is a common cause of failure. Owing to the increasing cost of copper, aluminium windings are increasingly used.

An even better material than copper, except for its high cost, would be silver as this has even lower resistivity. Silver has been used in rare cases. During World War II the Manhattan project to build the first atomic bomb used electromagnetic devices known as calutrons to enrich uranium. Thousands of tons of silver were borrowed from the U.S. Treasury reserves to build highly efficient low-resistance field coils for their magnets.[2][3]

See also

References

- Field coils are found in a vast array of electrical machines and so any attempt to categorise them in a readable manner is likely to exclude some obscure examples.

- Strictly it is the output power that is greater than the field power, although in practice this usually implies that the current is greater too.

- Hawkins Electrical Guide, Volume 1, Copyright 1917, Theo. Audel & Co., Chapter 14, Classes of Dynamo, page 182

- "The Silver Lining of the Calutrons". ORNL Review. Oak Ridge National Lab. 2002. Archived from the original on 2008-12-06.

- Smith, D. Ray (2006). "Miller, key to obtaining 14,700 tons of silver Manhattan Project". Oak Ridger. Archived from the original on 2007-12-17.