Financial risk management

Financial risk management is the practice of protecting economic value in a firm by managing exposure to financial risk - principally operational risk, credit risk and market risk, with more specific variants as listed aside. As for risk management more generally, financial risk management requires identifying the sources of risk, measuring these, and crafting plans to address them. [1] [2] See Finance § Risk management for an overview.

| Categories of |

| Financial risk |

|---|

| Credit risk |

| Market risk |

| Liquidity risk |

| Investment risk |

| Business risk |

| Profit risk |

| Non-financial risk |

Financial risk management as a "science" can be said to have been born [3] with modern portfolio theory, particularly as initiated by Professor Harry Markowitz in 1952 with his article, "Portfolio Selection";[4] see Mathematical finance § Risk and portfolio management: the P world.

The discipline can be qualitative and quantitative; as a specialization of risk management, however, financial risk management focuses more on when and how to hedge,[5] often using financial instruments to manage costly exposures to risk.[6]

- In the banking sector worldwide, the Basel Accords are generally adopted by internationally active banks for tracking, reporting and exposing operational, credit and market risks.[7][8]

- Within non-financial corporates,[9][10] the scope is broadened to overlap enterprise risk management, and financial risk management then addresses risks to the firm's overall strategic objectives.

- In investment management[11] risk is managed through diversification and related optimization; while further specific techniques are then applied to the portfolio or to individual stocks as appropriate.

In all cases, the last "line of defence" against risk is capital, "as it ensures that a firm can continue as a going concern even if substantial and unexpected losses are incurred".[12]

Economic perspective

Neoclassical finance theory - i.e., financial economics - prescribes that a firm should take on a project if it increases shareholder value. [13] Finance theory also shows that firm managers cannot create value for shareholders or investors by taking on projects that shareholders could do for themselves at the same cost; see Theory of the firm and Fisher separation theorem.

There is therefore a fundamental debate relating to "Risk Management" and shareholder value. [5] [14] [15] The discussion essentially weighs the value of risk management in a market versus the cost of bankruptcy in that market: per the Modigliani and Miller framework, hedging is irrelevant since diversified shareholders are assumed to not care about firm-specific risks, whereas, on the other hand hedging is seen to create value in that it reduces the probability of financial distress.

When applied to financial risk management, this implies that firm managers should not hedge risks that investors can hedge for themselves at the same cost. [5] This notion is captured in the so-called "hedging irrelevance proposition": [16] "In a perfect market, the firm cannot create value by hedging a risk when the price of bearing that risk within the firm is the same as the price of bearing it outside of the firm."

In practice, however, financial markets are not likely to be perfect markets. [17] [18] [19] [20] This suggests that firm managers likely have many opportunities to create value for shareholders using financial risk management, wherein they have to determine which risks are cheaper for the firm to manage than the shareholders. Here, market risks that result in unique risks for the firm are commonly the best candidates for financial risk management. [21]

Application

As outlined, businesses are exposed, in the main, to market, credit and operational risk. A broad distinction [12] exists though, between financial institutions and non-financial firms - and correspondingly, the application of risk management will differ. Respectively:[12] For Banks and Fund Managers, "credit and market risks are taken intentionally with the objective of earning returns, while operational risks are a byproduct to be controlled". For non-financial firms, the priorities are reversed, as "the focus is on the risks associated with the business" - ie the production and marketing of the services and products in which expertise is held - and their impact on revenue, costs and cash flow, "while market and credit risks are usually of secondary importance as they are a byproduct of the main business agenda". (See related discussion re valuing financial services firms as compared to other firms.) In all cases, as above, risk capital is the last "line of defence".

Banking

| Specific banking frameworks |

|---|

| Market risk |

| Credit risk |

|

| Counterparty credit risk |

| Operational risk |

Banks and other wholesale institutions face various financial risks in conducting their business, and how well these risks are managed and understood is a key driver behind profitability, as well as of the quantum of capital they are required to hold.[22] Financial risk management in banking has thus grown markedly in importance since the Financial crisis of 2007–2008. [23] (This has given rise [23] to dedicated degrees and professional certifications.)

The major focus here is on credit and market risk, and especially through regulatory capital, includes operational risk. Credit risk is inherent in the business of banking, but additionally, these institutions are exposed to counterparty credit risk. Both are to some extent offset by margining and collateral; and the management is of the net-position. Large banks are also exposed to Macroeconomic systematic risk - risks related to the aggregate economy the bank is operating in[24] (see Too big to fail).

The discipline [25][26] [7][8] is, as outlined, simultaneously concerned with (i) managing, and as necessary hedging, the various positions held by the institution — both trading positions and long term exposures; and (ii) calculating and monitoring the resultant economic capital, as well as the regulatory capital under Basel III - with the latter as a floor. The calculations here are mathematically sophisticated, and within the domain of quantitative finance.

Broadly, calculations [26][25] are built for (i) on the "Greeks", the sensitivity of the price of a derivative to a change in its underlying parameters, as well as on the various other measures of exposure to market factors, such as DV01 for the sensitivity of a bond or swap to interest rates; and for (ii) on value at risk, or "VaR", an estimate of how much the investment or area in question might lose with a given probability in a set time period, with the bank holding economic “risk capital” correspondingly.

The regulatory capital quantum is calculated via specified formulae: risk weighting the exposures per highly standardized asset-categorizations, applying the aside frameworks, and the resultant capital - at least 12.9% of these Risk-weighted assets - must then be held in specific "tiers" and is measured correspondingly. In certain cases, banks are allowed to use their own estimated risk parameters here; these "internal ratings-based models" typically result in less required capital, but at the same time are subject to strict minimum conditions and disclosure requirements.

The financial crisis exposed holes in the mechanisms used for hedging; see Fundamental Review of the Trading Book § Background, Tail risk § Role of the global financial crisis (2007-2008), Value at risk § Criticism, and Basel III § Criticism. As such, the methodologies employed have had to evolve:

- A core technique continues to be Value at Risk — applying the traditional parametric and "Historical" approaches — but now supplemented [26] with the more sophisticated Conditional value at risk / expected shortfall, Tail value at risk, and Extreme value theory (and PFE and EE for regulatory). For the underlying mathematics, these may utilize mixture models, PCA, volatility clustering, copulas, and other techniques.[27]

- For the daily direct analysis of the positions at the desk level, as a standard, measurement of the Greeks now inheres the volatility surface — through local- or stochastic volatility models — while re interest rates, discounting and analytics are under a "multi-curve framework". Derivative pricing now embeds counterparty and other considerations [28] through the CVA and XVA "valuation adjustments".

- Additional to these,[26] are various forms of stress test[29] and scenario analytics, and related economic capital optimization. These tests are typically linked to the macroeconomics, and provide an indicator of how sensitive the bank is to changes in economic conditions, and of its ability to respond to market events. And here, more generally, providing estimates for scenarios beyond the VaR thresholds, thus “preparing for anything that might happen,” rather than worrying about precise likelihoods.[30]

- Model risk is addressed [31] through regular validation of the models used by the bank's various divisions; for VaR models, backtesting.

- Under what is sometimes called "Basel IV", several regulatory capital standards have been modified, in particular via FRTB and SA-CCR; other modifications are being phased in from 2023.

Re implementation, Investment banks, particularly, employ dedicated "Risk Groups", i.e. Middle office teams monitoring the firm's risk exposure to, and the profitability and structure of, its various businesses, products, asset classes, desks, and / or geographies.[32] By increasing order of aggregation: (i) Financial institutions will typically [25] set limit values for each of the Greeks, or other measures, that their traders must not exceed, and traders will then hedge, offset, or reduce periodically if not daily - see the techniques listed below. (ii) Desks, or areas, will similarly be limited as to their VaR quantum (total or incremental, and under various calculation regimes), corresponding to their allocated economic capital; a loss which exceeds the VaR threshold is termed a "VaR breach". Allocated regulatory capital is similarly monitored. (iii) Each area's (or desk's) concentration risk will be checked [33][32][34] against thresholds set for various types of risk, and / or re a single counterparty, sector or geography. (iv) Leverage will be monitored - at very least re regulatory requirements - as leveraged positions could lose large amounts for a relatively small move in the price of the underlying. (v) Periodically,[35] these all are estimated under a given stress scenario, and risk capital - together with these limits - [36] is correspondingly revisited.

A key practice, [37] overlapping and assimilating these, is to assess the Risk-adjusted return on capital, RAROC, of each area (or product). Here,[38] the (ex-post) economic return is divided by allocated-capital; and this result is then compared [38][22] to the target-return for the area — usually, at least the equity holders' expected returns on the bank stock [38] — and identified under-performance can then be addressed. (See similar below re. DuPont analysis.) The numerator here is calculated as achieved trading-return, less a risk- and term-appropriate funding charge determined under the bank's funds transfer pricing (FTP) framework; direct costs are sometimes also subtracted. The denominator is the area's allocated capital, as above, increasing as a function of position risk. [39] [40] [37]

Other teams, overlapping the above Groups, are then also involved in risk management. In their Front office, Banks employ specialized XVA-desks tasked with centrally monitoring and managing their CVA and XVA exposure, typically with oversight from the appropriate Group.[28] Middle office maintains the following functions also: Product Control is primarily responsible for insuring traders mark their books to fair value (a key protection against rogue traders) and for "explaining" the daily P&L. Credit Risk monitors the bank's debt-clients on an ongoing basis, re both exposure and performance. Corporate Treasury is (co)responsible for maintaining the FTP framework, and for monitoring overall funding, capital structure, and liquidity risk (reviewing i.a. Liquidity at risk, Earnings at risk, and Cash flow at risk).

Performing the above tasks — while simultaneously ensuring that computations are consistent over the various areas, products, teams, and measures — requires that banks maintain a significant investment in sophisticated infrastructure, finance / risk software (the quantitative models, typically built in-house), and dedicated staff. Risk software often deployed is from FIS, Kamakura / SAS, Murex, and Numerix.

Corporate finance

In corporate finance and financial management, [41] [10] financial risk management, as above, is concerned more generally with business risk - risks to the business’ value, within the context of its business strategy and capital structure. [42] The scope here - ie in non-financial firms [12] - is thus broadened [9] [43] [44] (re banking) to overlap enterprise risk management, and financial risk management then addresses risks to the firm's overall strategic objectives, incorporating various (all) financial aspects [45] of the exposures and opportunities arising from business decisions, and their link to the firm’s appetite for risk, as well as their impact on share price. In many organizations, risk executives are therefore involved in strategy formulation: "the choice of which risks to undertake through the allocation of its scarce resources is the key tool available to management." [46]

Re the standard framework,[45] then, the discipline largely focuses on operations, i.e. business risk, as outlined. Here, the management is ongoing [10] — see following description — and is coupled with the use of insurance, [47] managing the net-exposure as above: credit risk is usually addressed via provisioning and credit insurance; likewise, where this treatment is deemed appropriate, specifically identified operational risks are also insured.[44] Market risk, in this context,[12] is concerned mainly with changes in commodity prices, interest rates, and foreign exchange rates, and any adverse impact due to these on cash flow and profitability, and hence share price.

Correspondingly, the practice here covers two perspectives; these are shared with corporate finance more generally:

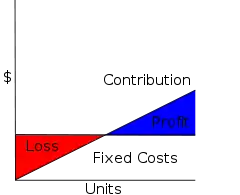

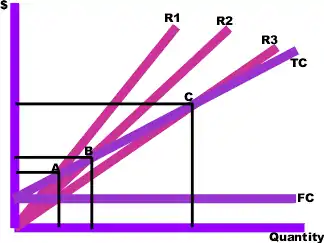

- Both risk management and corporate finance share the goal of enhancing, or at least preserving, firm value.[41] Here,[9][45] businesses devote much time and effort to (short term) liquidity-, cash flow- and performance monitoring, and Risk Management then also overlaps cash- and treasury management, especially as impacted by capital and funding as above. More specifically re business-operations, management emphasizes their break even dynamics, contribution margin and operating leverage, and the corresponding monitoring and management of revenue, of costs, and of other budget elements. The DuPont analysis entails a "decomposition" of the firm's return on equity, ROE, allowing management to identify and address specific areas of concern,[48] preempting any underperformance vs shareholders' required return.[49] In larger firms, specialist Risk Analysts complement this work with model-based analytics more broadly;[50][51] in some cases, employing sophisticated stochastic models,[51][52] in, for example, financing activity prediction problems, and for risk analysis ahead of a major investment.

- Firm exposure to long term market (and business) risk is a direct result of previous capital investment decisions. Where applicable here [12][45][41] — usually in large corporates and under guidance from [53] their investment bankers — risk analysts will manage and hedge [47] their exposures using traded financial instruments to create commodity-,[54][55] interest rate-[56][57] and foreign exchange hedges [58][59] (see further below). Because company specific, "over-the-counter" (OTC) contracts tend to be costly to create and monitor — i.e. using financial engineering and / or structured products — ”standard” derivatives that trade on well-established exchanges are often preferred. [14][45] These comprise options, futures, forwards, and swaps; the "second generation" exotic derivatives usually trade OTC. Complementary to this hedging, periodically, Treasury may also adjust the capital structure, reducing financial leverage - i.e. debt-funding - so as to accommodate increased business risk (they may also suspend dividends [60]).

Multinational corporations are faced with additional challenges, particularly as relates to foreign exchange risk, and the scope of financial risk management modifies significantly in the international realm.[58] Here, dependent on time horizon and risk sub-type — transactions exposure[61] (essentially that discussed above), accounting exposure,[62] and economic exposure [63] — so the corporate will manage its risk differently. Note that the forex risk-management discussed here and above, is additional to the per transaction "forward cover" that importers and exporters purchase from their bank (alongside other trade finance mechanisms).

It is common for large corporations to have dedicated risk management teams — typically within FP&A or corporate treasury — reporting to the CRO; often these overlap the internal audit function (see Three lines of defence). For small firms, it is impractical to have a formal risk management function, but these typically apply the above practices, at least the first set, informally, as part of the financial management function; see discussion under Financial analyst. Correspondingly, the discipline relies on a range of software,[64] from spreadsheets (invariably as a starting point, and frequently in total [65]) through commercial EPM and BI tools, often BusinessObjects (SAP), OBI EE (Oracle), Cognos (IBM), and Power BI (Microsoft).

Hedging-related transactions will attract their own accounting treatment, and corporates (and banks) may then require changes to systems, processes and documentation; [66] [67] see Hedge accounting, Mark-to-market accounting, Hedge relationship (finance), Cash flow hedge, IFRS 7, IFRS 9, FASB 133, IAS 39, FAS 130.

Investment management

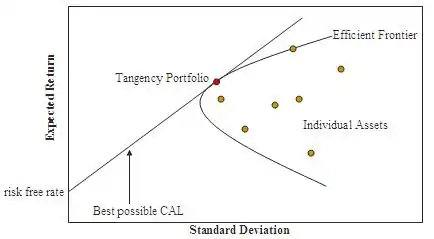

Fund managers, classically,[68] define the risk of a portfolio as its variance[11] (or standard deviation), and through diversification the portfolio is optimized so as to achieve the lowest risk for a given targeted return, or equivalently the highest return for a given level of risk; these risk-efficient portfolios form the "Efficient frontier" (see Markowitz model). The logic here is that returns from different assets are highly unlikely to be perfectly correlated, and in fact the correlation may sometimes be negative. In this way, market risk particularly, and other financial risks such as inflation risk (see below) can at least partially be moderated by forms of diversification.

A key issue in diversification, however, is that the (assumed) relationships are (implicitly) forward looking. As observed in the late-2000s recession historic relationships can break down, resulting in losses to market participants believing that diversification would provide sufficient protection (in that market, including funds that had been explicitly set up to avoid being affected in this way[69]). A related issue is that diversification has costs: as correlations are not constant it may be necessary to regularly rebalance the portfolio, incurring transaction costs, negatively impacting investment performance;[70] and as the fund manager diversifies, so this problem compounds (and a large fund may also exert market impact). See Modern portfolio theory § Criticisms.

Addressing these issues, more sophisticated approaches have been developed in recent times, both to defining risk, and to the optimization itself. (Respective examples: (tail) risk parity, focuses on allocation of risk, rather than allocation of capital; the Black–Litterman model modifies the "Markowitz optimization", to incorporate the views of the portfolio manager. [71]) Relatedly, modern financial risk modeling employs a variety of techniques — including value at risk, historical simulation, stress tests, and extreme value theory — to analyze the portfolio and to forecast the likely losses incurred for a variety of risks and scenarios. In parallel, [72] managers - active and passive - also seek to understand any tracking error, i.e. underperformance vs a "benchmark", and here often use attribution analysis preemptively so as to diagnose the source early, and to take corrective action (see also Fixed-income attribution); they similarly use style analysis to address style drift. Fund Managers typically rely on sophisticated software here (as do banks, above); widely used platforms are provided by BlackRock, Eikon, Finastra, Murex, Numerix, MPI and Morningstar.

Additional to these (improved) diversification and optimization measures, and given these analytics, Fund Managers will apply specific risk hedging techniques as appropriate;[68] [11] these may relate to the portfolio as a whole or to individual holdings.

- Fund managers may engage in portfolio insurance, a hedging strategy developed to limit the losses an investor might face from a declining index of stocks without having to sell the stocks themselves. This strategy involves selling Stock market index futures during periods of price declines. The proceeds from the sale of the futures help to offset paper losses of the owned portfolio. Alternatively, and more commonly,[73] they will buy a put on a Stock market index option so as to hedge. In both cases the logic is that the (diversified) portfolio is likely highly correlated with the stock index it is part of; thus if stock prices decline, the larger index will likewise decline, and the derivative holder will profit.[74] (Inflation, which affects all securities, [75] can to some extent be hedged using inflation-linked bonds;[76] diversification here is achieved by including tangible assets and commodities in the portfolio.[77])

- Fund managers, or traders, may also wish to hedge a specific stock's price. Here, they may likewise [74] buy a single-stock put, or sell a single-stock future. Alternative strategies may rely on assumed relationships between related stocks, employing, for example, a "Long/short" strategy.

- Bond portfolios, when e.g. a component of an Asset-allocation fund or other diversified portfolio, are typically managed similar to equity above: the Fund Manager will hedge her bond allocation with bond index futures or options.[78][79][74] In other contexts, the concern may be the net-obligation or net-cashflow. Here the fund manager employs Interest rate immunization or cashflow matching. Immunization is a strategy that ensures that a change in interest rates will not affect the value of a fixed-income portfolio (an increase in rates results in a decreased instrument value). It is often used to ensure that the value of a pension fund's assets (or an asset manager's fund) increase or decrease in an exactly opposite fashion to their liabilities, thus leaving the value of the pension fund's surplus (or firm's equity) unchanged, regardless of changes in the interest rate. Cashflow matching is similarly a process of hedging in which a company or other entity matches its cash outflows - i.e., financial obligations - with its cash inflows over a given time horizon.

- For individual bonds and other fixed income securities, specific credit and interest rate risks can be hedged using interest rate- and credit derivatives. Sensitivities re interest rates are measured using duration and convexity for bonds, and DV01 and key rate durations generally, and an offsetting derivative-position is purchased. For credit risk, analysts use models such as Jarrow–Turnbull and KMV to estimate the probability of default, hedging where appropriate. (At a portfolio level — often for credit-VaR — they may also use a transition matrix of Bond credit ratings [80] to estimate the probability and impact of a "credit migration",[81][82] aggregating the bond-by-bond result.) Interest rate- and credit risk together, may be hedged via a Total return swap. See Fixed income analysis

- For derivative portfolios, and positions, the Greeks are a vital risk management tool: as above, these measure sensitivity to a small change in a given underlying price, rate, or parameter, and the portfolio is then rebalanced accordingly[74] by including additional derivatives with offsetting characteristics, or by purchasing or selling specified units of the underlying security.

See also

- Articles

- Asset and liability management

- Corporate governance

- Enterprise risk management

- Finance § Risk management

- Risk management § Finance

- Lists

Bibliography

- Allen, Steve L. (2012). Financial Risk Management: A Practitioner's Guide to Managing Market and Credit Risk (2 ed.). John Wiley. ISBN 978-1118175453.

- Baker, H. Kent; Filbeck, Greg (2015). Investment Risk Management. Oxford Academic. ISBN 978-0199331963.

- Baranoff, Etti; Brockett, Patrick; Kahane, Yehuda (2009). Risk Management for Enterprises and Individuals. Saylor. ISBN 9780982361801.

- Blunden, Tony; Thirlwell, John (2021). Mastering Risk Management. FT Publishing International. ISBN 978-1292331317.

- Coleman, Thomas (2011). A Practical Guide to Risk Management (PDF). CFA Institute. ISBN 978-1-934667-41-5.

- Crockford, Neil (1986). An Introduction to Risk Management (2 ed.). Woodhead-Faulkner. ISBN 0-85941-332-2.

- Crouhy, Michel; Galai, Dan; Mark, Robert (2013). The Essentials of Risk Management (2 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 9780071818513.

- Christoffersen, Peter (2011). Elements of Financial Risk Management (2 ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-374448-7.

- Damodaran, Aswath (2007). Strategic Risk Taking: A Framework for Risk Management. FT Press. ISBN 978-0137043774.

- Hampton, John (2011). The AMA Handbook of Financial Risk Management. American Management Association. ISBN 978-0814417447.

- Hull, John (2023). Risk Management and Financial Institutions (6 ed.). John Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-93248-2.

- Lam, James (2003). Enterprise Risk Management: From Incentives to Controls. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-43000-1.

- McNeil, Alexander J.; Frey, Rüdiger; Embrechts, Paul (2015), Quantitative Risk Management. Concepts, Techniques and Tools, Princeton Series in Finance (revised ed.), Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691166278, MR 2175089, Zbl 1089.91037

- Roncalli, Thierry (2020). Handbook of Financial Risk Management. Chapman & Hall. ISBN 9781138501874.

- Tapiero, Charles (2004). Risk and Financial Management: Mathematical and Computational Methods. John Wiley & Son. ISBN 0-470-84908-8.

- van Deventer; Donald R.; Kenji Imai; Mark Mesler (2004). Advanced Financial Risk Management: Tools and Techniques for Integrated Credit Risk and Interest Rate Risk Management. John Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-82126-8.

References

- Peter F. Christoffersen (22 November 2011). Elements of Financial Risk Management. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-374448-7.

- Financial Risk Management, Finance Glossary. Gartnergartner.com

- W. Kenton (2021). "Harry Markowitz", investopedia.com

- Markowitz, H.M. (March 1952). "Portfolio Selection". The Journal of Finance. 7 (1): 77–91. doi:10.2307/2975974. JSTOR 2975974.

- See § "Does Corporate Risk Management Create Value?" in Capital Budgeting Applications and Pitfalls. Ch 13 of Ivo Welch (2022). Corporate Finance, 5 Ed. IAW Publishers. ISBN 978-0984004904

- Allan M. Malz (13 September 2011). Financial Risk Management: Models, History, and Institutions. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-02291-7.

- Van Deventer, Nicole L, Donald R., and Kenji Imai. Credit risk models and the Basel Accords. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons (Asia), 2003.

- Drumond, Ines. "Bank capital requirements, business cycle fluctuations and the Basel Accords: a synthesis." Journal of Economic Surveys 23.5 (2009): 798-830.

- John Hampton (2011). The AMA Handbook of Financial Risk Management. American Management Association. ISBN 978-0814417447

- Jayne Thompson (2019). What Is Financial Risk Management?, chron.com

- Will Kenton (2023). What Is Risk Management in Finance, and Why Is It Important?, investopedia.com

- See "Market Risk Management in Non-financial Firms", in Carol Alexander, Elizabeth Sheedy eds. (2015). The Professional Risk Managers’ Handbook 2015 Edition. PRMIA. ISBN 978-0976609704

- See for example, "Corporate Finance: First Principles", in Aswath Damodaran (2014). Applied Corporate Finance. Wiley. ISBN 978-1118808931

- Jonathan Lewellen (2003). Financial Management - Risk Management. MIT OCW

- Why Corporations Hedge; Ch 3.7 in Baranoff et. al.

- KRISHNAMURTI CHANDRASEKHAR; Krishnamurti & Viswanath (eds.) "; Vishwanath S. R. (2010-01-30). Advanced Corporate Finance. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. pp. 178–. ISBN 978-81-203-3611-7.

- John J. Hampton (1982). Modern Financial Theory: Perfect and Imperfect Markets. Reston Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8359-4553-0.

- Zahirul Hoque (2005). Handbook of Cost and Management Accounting. Spiramus Press Ltd. pp. 201–. ISBN 978-1-904905-01-1.

- Kirt C. Butler (28 August 2012). Multinational Finance: Evaluating Opportunities, Costs, and Risks of Operations. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-118-28276-2.

- Dietmar Franzen (6 December 2012). Design of Master Agreements for OTC Derivatives. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-3-642-56932-6.

- Corporate Finance: Part I. Bookboon. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-87-7681-568-4.

- Fadi Zaher (2022). Using Economic Capital to Determine Risk, investopedia.

- The Rise of the Chief Risk Officer, Institutional Investor (March 2017).

- Bolt, Wilko; Haan, Leo de; Hoeberichts, Marco; Oordt, Maarten van; Swank, Job (September 2012). "Bank Profitability during Recessions" (PDF). Journal of Banking & Finance. 36 (9): 2552–64. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2012.05.011.

- Martin Haugh (2016). "Basic Concepts and Techniques of Risk Management". Columbia University

- Roy E. DeMeo (N.D.) "Quantitative Risk Management: VaR and Others". UNC Charlotte

- See for example III.A.3, in Carol Alexander, ed. (January 2005). The Professional Risk Managers' Handbook. PRMIA Publications. ISBN 978-0976609704

- International Association of Credit Portfolio Managers (2018). "The Evolution of XVA Desk Management"

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2009). "Principles for sound stress testing practices and supervision"

- David Aldous (2016). Review of Financial Risk Management... for Dummies

- Riccardo Rebonato (N.D.). Theory and Practice of Model Risk Management.

- International Association of Credit Portfolio Managers (2022). "Risk mitigation techniques in credit portfolio management"

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (1999). "Risk Concentrations Principles"

- "Principles for the Management of Concentration Risk" (PDF). Malta Financial Services Authority. 2010.

- Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2009). "Range of practices and issues in economic capital frameworks"

- Financial Stability Board (2013). "Principles for An Effective Risk Appetite Framework"

- Michel Crouhy (2006). "Risk Management, Capital Attribution and Performance Measurement"

- J Skoglund (2010). "Funds Transfer Pricing and Risk Adjusted Performance Measurement". SAS Institute.

- Karen Moss (2018). "Funds-transfer-pricing in Banks: what are the main drivers?". Moodys Analytics

- James Chen (2021). Risk-Adjusted Return on Capital (RAROC) Explained & Formula, Investopedia

- Risk Management and the Financial Manager. Ch. 20 in Julie Dahlquist, Rainford Knight, Alan S. Adams (2022). Principles of Finance. OpenStax, Rice University. ISBN 9781951693541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Will Kenton (2022). "Business Risk", Investopedia

- Stanley Myint (2022). Introduction to Corporate Financial Risk Management. PRMIA Thought Leadership Webinar

- "Risk Management and the Firm’s Financial Statement — Opportunities within the ERM" in Esther Baranoff, Patrick Brockett, Yehuda Kahane (2012). Risk Management for Enterprises and Individuals. Saylor Academy

- Margaret Woods and Kevin Dowd (2008). Financial Risk Management for Management Accountants, Chartered Institute of Management Accountants

- Don Chance and Michael Edleson (2021). Introduction to Risk Management. Ch 10 in "Derivatives". CFA Institute Investment Series. ISBN 978-1119850571

- Managing financial risks; summary of Ch. 51 in: Pascal Quiry; Yann Le Fur; Antonio Salvi; Maurizio Dallochio; Pierre Vernimmen (2011). Corporate Finance: Theory and Practice (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-1119975588

- Marshall Hargrave (2022). Dupont Analysis, Investopedia.

- See discussion under § Shareholder Value, ROE, and Cash Flow Analyses in: Jamie Pratt and Michael Peters (2016). Financial Accounting in an Economic Context (10th Edition). Wiley Finance. ISBN 978-1-119-30616-0

- See §39 "Corporate Planning Models", and §294 "Simulation Model" in Joel G. Siegel; Jae K. Shim; Stephen Hartman (1 November 1997). Schaum's quick guide to business formulas: 201 decision-making tools for business, finance, and accounting students. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-058031-2. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- David Shimko (2009). Quantifying Corporate Financial Risk. archived 2010-07-17.

- See for example this problem (from John Hull's Options, Futures, and Other Derivatives), discussing cash position modeled stochastically.

- David Shimko (2009). Dangers of Corporate Derivative Transactions

- Deloitte / MCX (2018). Commodity price risk management

- CPA Australia (2012). A guide to managing commodity risk

- Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (N.D.). Interest rate risk management

- CPA Australia (2008). Understanding and Managing Interest Rate Risk

- Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (N.D.). Foreign currency risk and its management

- CPA Australia (2009). A guide to managing foreign exchange risk

- Claire Boyte-White (2023). 4 Reasons a Company Might Suspend Its Dividend, Investopedia

- "Contrary to conventional wisdom it may be rational to hedge translation exposure.": Raj Aggarwal (1991). "Management of Accounting Exposure to Currency Changes: Role and Evidence of Agency Costs". Managerial Finance, Vol. 17 No. 4, pp. 10-22.

- Aggarwal, Raj, "The Translation Problem in International Accounting: Insights for Financial Management." Management International Review 15 (Nos. 2-3, 1975): 67-79. (Proposed accounting framework for evaluating and developing translation procedures for multinational corporations).

- Aggarwal, Raj; DeMaskey, Andrea L. (April 30, 1997). "Cross-Hedging Currency Risks in Asian Emerging Markets Using Derivatives in Major Currencies". The Journal of Portfolio Management. 23 (3): 88–95. doi:10.3905/jpm.1997.409611. S2CID 153476555.

- See: "Financial Management System (FMS) - Gartner Finance Glossary". Gartner. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- Jeremy Fabbri (2020). Should You Use Spreadsheets for Risk Management?

- Price Waterhouse Coopers (2017). Achieving hedge accounting in practice under IFRS 9

- Conti, Cesare & Mauri, Arnaldo (2008). "Corporate Financial Risk Management: Governance and Disclosure post IFRS 7", Icfai Journal of Financial Risk Management, ISSN 0972-916X, Vol. V, n. 2, pp. 20–27.

- Pamela Drake and Frank Fabozzi (2009). What Is Finance?

- Khandani, Amir E.; Lo, Andrew W. (2007). "What Happened To The Quants In August 2007?∗" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - William F. Sharpe (1991). "The Arithmetic of Active Management" Archived 2013-11-13 at the Wayback Machine. Financial Analysts Journal Vol. 47, No. 1, January/February

- Guangliang He and Robert Litterman (1999). "The Intuition Behind Black-Litterman Model Portfolios". Goldman Sachs Quantitative Resources Group

- Carl Bacon (2019). “Performance Attribution History and Progress”. CFA Institute Research Foundation

- Staff (2020). What is index option trading and how does it work?, Investopedia

- For discussion and examples re calculating the appropriate "optimal hedge ratio", and then executing, see: Roger G . Clarke (1992). "Options and Futures: A Tutorial". CFA Institute Research Foundation

- Troy Segal (2022). "What is inflation and how does inflation affect investments?". Investopedia

- Inflation-Linked Bonds (ILBs), PIMCO.

- Staff (2022-01-31). "Managing Portfolio Risk in A High-Inflation Market". KLO Financial Services. Retrieved 2023-05-12.

- Staff (2020). How to hedge your bond portfolio against falling rates, bloomberg.com

- Jeffrey L. Stouffer (2011). Protecting A Bond Portfolio With Futures Contracts, Financial Advisor Magazine

- Paul Glasserman (2000). Probability Models of Credit Risk

- Mukul Pareek (2021). "Credit Migration Framework"

- Staff (2021). How Credit Rating Risk Affects Corporate Bonds, Investopedia

External links

- CERA - The Chartered Enterprise Risk Analyst Credential - Society of Actuaries (SOA)

- Financial Risk Manager Certification Program - Global Association of Risk Professionals (GARP)

- Professional Risk Manager Certification Program - Professional Risk Managers' International Association (PRMIA)

- Risk Journals Homepage