Florida State University

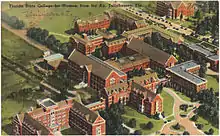

Florida State University (FSU) is a public research university in Tallahassee, Florida, United States. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida. Founded in 1851, it is located on Florida's oldest continuous site of higher education.[2][4]

| |

Former names | Florida Institute (1854–1857) Tallahassee Female Academy (1843–1858) West Florida Seminary (1857–1860; 1865–1901) The Florida Military and Collegiate Institute (1860–1865) The Literary College of the University of Florida (1883–1885) University of Florida (1885-1902) Florida State College (1901–1905) Florida Female College (1905) Florida State College for Women (1905–1947) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Vires, Artes, Mores (Latin) |

Motto in English | "Strength, Skill, Character" |

| Type | Public research university |

| Established | January 24, 1851[note 1] |

Parent institution | State University System of Florida |

| Accreditation | SACS |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $897.6 million (2021)[5] |

| Budget | $2.17 billion (2021) |

| President | Richard D. McCullough |

| Provost | James J. Clark |

Academic staff | 5,966[6] |

Administrative staff | 8,133[7] |

| Students | 45,493 (fall 2021)[8] |

| Undergraduates | 33,486 (fall 2021)[8] |

| Postgraduates | 12,007 (fall 2021)[8] |

| Location | , , United States 30.442°N 84.298°W |

| Campus | Midsize city[9], 487.5 acres (1.973 km2)[10] (Main Campus)

Total, 1,715.5 acres (6.942 km2)[10] |

| Other campuses | |

| Newspaper |

|

| Colors | Garnet and gold[11] |

| Nickname |

|

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I FBS – ACC |

| Mascot |

|

| Website | www |

Florida State University comprises 16 separate colleges and more than 110 centers, facilities, labs, and institutes that offer more than 360 programs of study, including professional school programs.[12] In 2021, the university enrolled 45,493 students from all 50 states and 130 countries.[8] Florida State is home to Florida's only national laboratory, the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, and is the birthplace of the commercially viable anti-cancer drug Taxol. Florida State University also operates the John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida and one of the nation's largest museum/university complexes.[13] The university is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS).

Florida State University is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[14] In 2020, the university had research and development (R&D) expenditures of $350.4 million, ranking it 75th in the nation.[15] The university has an annual budget of over $2.17 billion and an annual economic impact of $14 billion.[16][17]

FSU's intercollegiate sports teams, commonly known by their "Florida State Seminoles" nickname, compete in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I and the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC). In their 113-year history, Florida State's varsity sports teams have won 20 national athletic championships, and Seminole athletes have won 78 individual NCAA national championships.[18]

History

In 1819, the Florida Territory was ceded to the United States by Spain as an element of the Adams–Onís Treaty.[19] The Territory was conventionally split by the Appalachicola or later the Suwannee rivers into East and West areas. Florida State University is traceable to a plan set by the 1823 U.S. Congress to create a higher education system.[20] The 1838 Florida Constitution codified the primary system by providing for land allocated for the schools.[21] In 1845 Florida became the 27th State of the United States, which permitted the resources and intent of the 1823 Congress regarding education in Florida to be implemented.

The Legislature of the State of Florida, in a Legislative Act of January 24, 1851, provided for establishing the two institutions of learning on opposite sides of the Suwannee River. The Legislature declared the purpose of these institutions to be "the instruction of persons, both male, and female, in the art of teaching all the various branches that pertain to a good common school education; and next to instruct in the mechanic arts, in husbandry, in agricultural chemistry, in the fundamental laws, and in what regards the rights and duties of citizens."[22] By 1854 the City of Tallahassee had established a school for boys called the Florida Institute, with the hope that the State could be induced to take it over as one of the seminaries. In 1856, Tallahassee Mayor Francis W. Eppes again offered the institute's land and building to the Legislature. The bill to locate the Seminary in Tallahassee passed both houses and was signed by the Governor on January 1, 1857. On February 7, 1857, the first meeting of the Board of Education of the State Seminary West of the Suwannee River was held, and the institution began offering post-secondary instruction to male students. Francis Eppes served as the Seminary's Board of Education president for eight years.[22] In 1858 the seminary absorbed the Tallahassee Female Academy, established in 1843, and became coeducational.[23]

The West Florida Seminary was located on the former Florida Institute property, a hill where the historic Westcott Building now stands. The location is the oldest continuously used site of higher education in Florida. The area, slightly west of the state Capitol, was formerly and ominously known as Gallows Hill, a place for public executions in early Tallahassee.[24]

Civil War and Reconstruction

In 1860–1861, the legislature started formal military training at the school with a law amending the original 1851 statute.[25] During the Civil War, the seminary became The Florida Military and Collegiate Institute. Enrollment at the school increased to around 250 students, establishing itself as perhaps the largest and most respected educational institution in the state.[25] Cadets from the school defeated Union forces at the Battle of Natural Bridge in 1865, leaving Tallahassee as the only Confederate capital east of the Mississippi River not to fall to Union forces.[26][27] The students were trained by Valentine Mason Johnson, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute, who was a professor of mathematics and the chief administrator of the college.[28] After the fall of the Confederacy, Union military forces occupied campus buildings for approximately four months and the West Florida Seminary reverted to its former academic purpose.[29] In recognition of the cadets and their pivotal role in the battle, the Florida State University Army ROTC cadet corps displays a battle streamer bearing the words "NATURAL BRIDGE 1865" with its flag. The FSU Army ROTC is one of only four collegiate military units in the United States with permission to display such a pennant.[30]

First state university

In 1883, the institution, now long officially known as the West Florida Seminary, was organized by the Board of Education as The Literary College of the University of Florida. (In the terminology of the time, schools were divided into seminaries and literary institutions; the name does not imply a focus on literature.) Under the new university charter, the seminary became the institution's Literary College and was to contain several "schools" or departments in different disciplines.[31] However, in the new university association the seminary's "separate Charter and special organization" were maintained.[32] Florida University also incorporated the Tallahassee College of Medicine and Surgery, and recognized three more colleges to be established at a later date.[31] The Florida Legislature recognized the university under the title " University of Florida" in Spring 1885 but committed no additional financing or support.[22][33] Without legislative support, the university project struggled. The institution never assumed the "university" title,[33] and the association dissolved when the medical college relocated to Jacksonville later that year.[31]

The West Florida Seminary, as it was still generally called, continued to expand and thrive. It shifted its focus towards modern-style post-secondary education, awarding "Licentiates of Instruction," its first diplomas, in 1884,[22] and became Florida's first liberal arts college in 1897.[22] By 1891, the institute had begun to focus on modern post-secondary education; seven Bachelor of Arts degrees were awarded that year.[22]

However, according to Dr. Doak Campbell, Florida State University's first president, "During the first 50 years...its activities were limited to courses of secondary-school grade. Progress was slow. Indeed, it was not until the turn of the [twentieth] century that it could properly qualify as a collegiate institution."[34]

In 1901, it became Florida State College, a four-year institution organized into four departments: the college, the School for Teachers, the School of Music, and the College Academy. Florida State College was empowered to award the degree of Master of Arts, and the first master's degree was offered in 1902. That year, the student body numbered 252 men and women, and degrees were available in classical, literary, and scientific studies. In 1903, the first university library was begun.[22]

Buckman Act

The 1905 Florida Legislature passed the Buckman Act, which reorganized the Florida college system into a school for white males (University of the State of Florida), a school for white females (Florida Female College later changed to Florida State College for Women), and a school for African Americans (State Normal and Industrial College for Colored Students).[35] The Buckman Act was controversial, as it changed the character of a historic coeducational state school into a school for women. An early and major benefactor of the school, James Westcott III (1839–1887), willed substantial monies to the school to support continued operations. In 1911, his estate sued the state educational board contending the estate was not intended to support a single-sex school. The Florida Supreme Court decided the issue in favor of the State of Florida stating the change in character (existing from 1905 to 1947) was within the intent of the Westcott will.[36] By 1933 the Florida State College for Women had grown to be the third largest women's college in the United States and was the first state women's college in the South to be awarded a chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, as well as the first university in Florida so honored.[37][38] Florida State was the largest of the original two state universities in Florida until 1919.[39]

"Florida State University"

Returning soldiers using the G.I. Bill after World War II stressed the state university system to the point that a Tallahassee Branch of the University of Florida (TBUF) was opened on the campus of the Florida State College for Women with the men housed in barracks on nearby Dale Mabry Field.[22] By 1947 the Florida Legislature returned the FSCW to coeducational status and designated it Florida State University.[40] The FSU West Campus land and barracks plus other areas continually used as an airport later became the location of the Tallahassee Community College. The post-war years brought substantial growth and development to the university as many departments and colleges were added, including Business, Journalism (discontinued in 1959), Library Science, Nursing, and Social Welfare.[41] Strozier Library, Tully Gymnasium and the original parts of the Business building were also built at this time.

Student activism and racial integration

During the 1960s and 1970s Florida State University became a center for student activism especially in the areas of racial integration, women's rights, and opposition to the Vietnam War. Student protests against censorship in FSU student publications led to the resignation of President John E. Champion in February 1969.[42] In 1972 Margaret Menzel, a professor in the biology department, led a class action lawsuit charging discrimination against women in pay and promotion.[43][44] The case was settled in 1975 with an agreement that the university would establish a task force to investigate bias against women at the university and to revise its anti-nepotism policy so as to not discriminate against the wives of university employees.[45]

The school acquired the nickname "Berkeley of the South"[46] during this period, in reference to similar student activities at the University of California, Berkeley. The school is also said to have originated the 1970s fad of "streaking", said to have been first observed on Landis Green.[47][48]

After many years as a whites-only university, in 1962 Maxwell Courtney became the first African-American undergraduate student admitted to Florida State.[49] In 1968 Calvin Patterson became the first African-American player for the Florida State University football team.[50] Florida State today has the highest graduation rate for African-American students of all universities in Florida.[51]

On March 4, 1969, the FSU chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, an unregistered university student organization, sought to use university facilities for meetings. The FSU administration, under President J. Stanley Marshall, subsequently decided not to allow the SDS the use of university property and obtained a court injunction to bar the group. The result was a protest and mass arrest at bayonet point of some 58 students in an incident later called the Night of the Bayonets.[52] The university Faculty Senate later criticized the administration's response as provoking as an artificial crisis.[53] Another notable event occurred when FSU students massed in protest of student deaths at Kent State University causing classes to be canceled.[54] Approximately 1000 students marched to the ROTC building where they were confronted by police armed with shotguns and carbines. Joining the all-night vigil, Governor Claude Kirk appeared unexpectedly with a wicker chair and spent hours, with little escort or fanfare, on Landis Green discussing politics with protesting students.[54]

The Pride Student Union (PSU), originally LGBSU, was founded in 1969 to represent LGBTQ students.[55][56] In 1980 a gay male named William Wade won the title of Homecoming Princess under the pseudonym "Billy Dahling" causing controversy.[57][58][59] In 2006 the Union Board added sexual orientation to its nondiscrimination policy causing several student organizations to be zero-funded for noncompliance. Christian Legal Society had the student senate reverse the freezing after threatening a lawsuit[60][61] which resulted in the founding of The Coalition for an Equitable Community (CFEC) to advocate for an inclusive nondiscrimination policy.[62][63] In 2008 CFEC filed suit with the FSU Student Supreme Court against the Union Board for failing to uphold the policy though they ruled they lacked jurisdiction after hearing the case.[64] In November 2009 CFEC placed an editorial in the FSView to provide perspective on the issue.[65] In June 2010 the University Board of Trustees passed a resolution protecting students based on sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression.[66]

21st century

In March 2002, FSU students pitched "Tent City" on Landis Green for 114 days to compel the university to join the fledgling Worker's Rights Consortium (WRC).[67] The Worker Rights Consortium (WRC) is an independent watchdog group that monitors labor rights worldwide. At the time, FSU earned $2 million a year from merchandising rights. FSU administration initially refused to meet with the WRC, reportedly for fear of harming its relationship with Nike.[67] At the outset of the protest 12 activists were arrested for setting up their tents outside the "free speech zone." The protest ended in July, when administration met student demands and met with the WRC.[67]

The Florida State University College of Medicine was created in June 2000.[68] It received provisional accreditation by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education on October 17, 2002, and full accreditation on February 3, 2005. The King Life Sciences Building, which sits next to the College of Medicine, was completed in June 2008, bringing all the biological sciences departments under one roof.

Following the creation of performance standards by the Florida Legislature in 2013, Florida Governor Rick Scott and the Florida Board of Governors designated Florida State University and the University of Florida as the two "preeminent universities" among the twelve universities of the State University System of Florida.[69][70] Florida State's new preeminent status called for an increased state commitment of $75 million, which was divided into $15 million increments from 2013 to 2018.[71] Among recent developments to the campus include the new FSU Student Union, opened in the summer of 2022, and dormitory renovation projects.

Campus

Tallahassee

The main campus covers 489 acres (2.0 km2) of land including Heritage Grove and contains over 14,800,000 square feet (1,375,000 m2) of buildings. Florida State University owns more than 1,600 acres (6 km2). The campus is bordered by Stadium Drive to the west, Tennessee Street (U.S. Route 90) to the north, Macomb Street to the east, and Gaines Street to the south. Located at the intersection of College Avenue and S. Copeland Street, the Westcott Building is perhaps the school's most prominent structure. The Westcott location is the oldest site of higher education in Florida[72] and is the home of Ruby Diamond Auditorium which serves as the university's premier performance venue.[73] Dodd Hall, the campus' original library was ranked as tenth on AIA's Florida Chapter list of Florida Architecture: 100 Years. 100 Places.[74]

The historic student housing residence halls include Broward, Bryan, Cawthon, Gilchrist, Jennie Murphree, Landis and Reynolds, and are located on the eastern half of campus. There are three new residence hall complexes, Ragans and Wildwood, located near the athletic quadrant; and DeGraff Hall, located on Tennessee Street. Being a major university campus, the Florida State University campus is also home to Heritage Grove, Florida State's Greek community, located a short walk up the St. Marks Trail.

On and around the Florida State University campus are nine libraries: Robert Manning Strozier Library, Dirac Science Library named after the Nobel Prize-winning physicist and Florida State University professor Paul Dirac, Claude Pepper Library, College of Music Allen Music Library, Innovation Hub, College of Law Research Center, College of Medicine Maguire Medical Library, Department of Religion's M. Lynette Thompson Classics Library,[75] and the FAMU/FSU Engineering Library.[76] Strozier Library is the main library of the campus and is the only library in Florida that is open 24 hours Sunday-Thursday throughout the Fall and Spring semesters.[77]

Right next to the Donald L. Tucker Center, the College of Law is located between Jefferson Street and Pensacola Street. The College of Business sits in the heart of campus near the FSU Student Union and across from the Huge Classroom Building (HCB). The science and research quad is located in the northwest quadrant of campus. The College of Medicine, King Life Science buildings (biology) as well as the Department of Psychology are located on the west end of campus on Call Street and Stadium Drive.

Located off Stadium Drive in the southwest quadrant are Doak Campbell Stadium which encloses Bobby Bowden Field. The arena seats approximately 84,000 spectators, the University Center, Mike Martin Field at Dick Howser Stadium, Coyle Moore Athletic Center as well as other athletic buildings. Doak Campbell Stadium is a unique venue in collegiate athletics. It is contained within the brick facade walls of University Center, the largest continuous brick structure in the world.[78] The vast complex houses the offices of the university, the registrar, the Dedman School of Hospitality, and other offices and classrooms.

Additional to the main campus, the FSU Southwest Campus encompasses another 850 acres (3.4 km2) of land off Orange Drive. The southwest campus currently houses the Florida A&M University – Florida State University College of Engineering, which is housed in a two-building joint facility with Florida A&M University. In addition to the College of Engineering, The Don Veller Seminole Golf Course and Club are located here and the Morcorm Aquatics Center. The FSU Research Foundation buildings as well as the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory are located in Innovation Park and the Alumni Village, family style student housing are located off Levy. Flastacowo Road Leads to the Florida State University Reservation, a student lakeside retreat on Lake Bradford.

Florida State University has seen considerable expansion and construction since T. K. Wetherell came into office in 2003. Numerous renovations as well as new constructions have been completed or are in the process of completion. These projects include student athletic fields, dormitories, new classroom space as well as research space. Currently the campus is undergoing a revival and beautification of the campus' main spaces.

Panama City

Florida State University Panama City is located 100 miles (160 km) from the main campus, beginning in the early 1980s. Since that time the campus has grown to almost 1,500 students supported by 15 bachelor's and 19 graduate degree programs.

FSU Panama City began offering full-time daytime programs in fall 2000. This scheduling, coupled with programs offered in the evenings, serves to accommodate the needs of its diverse student population. Over 30 resident faculty were hired to help staff the programs. The Florida State University Panama City campus offers upper-division undergraduate courses as well as some graduate and specialist degree programs.

Since opening in 1982, over 4,000 students have graduated from FSU Panama City with degrees ranging from elementary education to engineering. All courses are taught by faculty members from the main FSU campus. The satellite institution currently has a ratio of 25 students to each faculty member.[79]

Organization and administration

| College/school founding | |

|---|---|

| College/school | Year founded |

|

| |

| College of Arts & Sciences | 1901 |

| College of Human Sciences | 1901 |

| College of Education | 1901 |

| College of Music | 1901 |

| College of Social Work | 1928 |

| School of Dance | 1930 |

| College of Fine Arts | 1943 |

| College of Communication and Information | 1947 |

| School of Information | 1947 |

| Askew School of Public Administration and Policy | 1947 |

| Dedman School of Hospitality | 1947 |

| College of Business | 1950 |

| College of Nursing | 1950 |

| College of Law | 1966 |

| College of Social Sciences and Public Policy | 1973 |

| School of Theatre | 1973 |

| College of Criminology and Criminal Justice | 1974 |

| College of Engineering | 1983 |

| College of Motion Picture Arts | 1989 |

| College of Medicine | 2000 |

| School of Communication | 2009 |

| School of Communication Science and Disorders | 2009 |

| Jim Moran School of Entrepreneurship | 2017 |

| School of Physician Assistant Practice | 2017 |

As a part of the State University System of Florida, Florida State University falls under the purview of the Florida Board of Governors. However, a 13-member Board of trustees is "vested with the authority to govern and set policy for Florida State University as necessary to provide proper governance and improvement of the University in accordance with law and rules of the Florida Board of Governors".[80]

Jim Clark became the provost of FSU in January 2022, and is responsible for day-to-day operation and administration of the university.[81]

Florida State University is divided into 16 colleges and more than 110 centers, facilities, labs and institutes offering more than 300 degree programs.[82] Florida State University offers Associate, Bachelor, Masters, Specialist, Doctoral, and Professional degree programs. The most popular Colleges by enrollment are Arts and Sciences, Business, Social Sciences, Education, and Human Science.[83]

The Florida State University College of Medicine operates using diversified hospital and community-based clinical education medical training for medical students. Founded on the mission to provide care to medically under served populations, the Florida State University College of Medicine for patient-centered care. The students spend their first two years taking basic science courses on the FSU campus in Tallahassee and are then assigned to one of the regional medical school campuses for their third- and fourth-year clinical training. Rotations can be done at one of the six regional campuses in Daytona Beach, Fort Pierce, Orlando, Pensacola, Sarasota or stay in Tallahassee if they so choose.[84]

Finances

Fitch Ratings affirmed the FSU Issuer Default Rating at "AA+" on February 14, 2022, with a stable outlook.[85] Fitch's Analytical Conclusion as referenced, in part reads: As a comprehensive flagship university, FSU has a statewide and even national draw for students and has considerable fundraising capabilities. The Stable Outlook reflects Fitch's expectation that the university will sustain adjusted cash flow margins, as defined in Fitch's criteria, in line with historical trends, and that balance sheet strength will be maintained and improve over time.

As of 2021 FSU's university-wide total financial endowment was valued at $897.8 million.[86] Florida State University receives, in addition to state funding, financial support from the Florida State University Foundation, which had a financial endowment valued at $669 million as of June 30, 2021[87] The endowment helps provide scholarships to students, support teaching and research, and fund other specific purposes designated by donors.

Seminole Boosters

Seminole Boosters, Inc., is designated as the Direct Support Organization for Florida State University athletics.[88] Contributors account for more than $14 million in annual funds, plus at least $15 million per year in capital gifts. The Seminole Boosters Scholarship Endowment has nearly $66 million under management, and the Boosters are involved with a wide range of enterprises including affinity programs, logos and licensing, game-day parking, concessions, the University Center Club, skybox management, and the construction of athletic facilities.[89]

Student government

The Florida State University Student Government Association is the governing body of students who attend Florida State University, representing the university's nearly 43,000 undergraduate, graduate and professional students. The university's student government currently operates on a yearly $13.79 million budget, one of the largest student government budgets in the United States.[90]

The student government was established in 1935 and consists of executive, judicial, and legislative branches.[91] The student government executive branch is led by the student body president and includes the student body vice President, student body treasurer, six agencies, seven bureaus, and executive secretaries within the Executive Office of the President.

The Student Senate is the legislative branch, and is composed of 80 senators who serve one-year terms. The student body elects the first half during each spring semester and the remaining half during the fall semester. The senators elect a senate president and senate president pro tempore once a year, after the fall election, to lead the Student Senate.[92]

The student government judicial branch has two major components: the Supreme Court of the Student Body (headed by a chief justice) and all elections related officials such as the supervisor of elections and the Elections Commission. The Supreme Court consists of seven second or third-year students at the FSU College of Law nominated by the student body president and confirmed by the Student Senate.[93] Each justice serves a "life-time" term, which extends through the individual justice's graduation and insulates the court from the politics of student government. The chief justice may appoint a marshal and clerk. The election commission is also composed of Florida State University College of Law students and it adjudicates all student government election complaints. The commission has five members, one of whom also serves as the commission chairman.

Academics

Florida State University aspires to become a top twenty-five public research university with at least one-third of its PhD programs ranked in the top 15 nationally.[94] The university owns more than 1,600 acres (6.4 km2) and is the home of the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory among other advanced research facilities. The university continues to develop in its capacity as a leader in Florida graduate research. Other milestones at the university include the first ETA10-G/8 supercomputer,[95] capable of 10.8 GFLOPS in 1989, remarkable for the time in that it exceeded the existing speed record of the Cray-2/8, located at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory by a substantial leap and the development of the anti-cancer drug Taxol.

Florida State University is divided into 16 colleges and schools including the Colleges of Applied Studies, Arts & Sciences, Business, Communication & Information, Criminology & Criminal Justice, Education, Engineering, Fine Arts, Human Sciences, Law, Medicine, Motion Picture Arts, Music, Nursing, Social Sciences & Public Policy, and Social Work, plus the Graduate School, Dedman School of Hospitality, and the Jim Moran School of Entrepreneurship. Florida State offers 104 baccalaureate degree programs, 112 master's degree programs, an advanced master's degree program, 12 specialist degree programs, 70 doctorate degree programs, and 3 professional degree programs.[96] The most popular Colleges by enrollment are Arts and Sciences, Business, Social Sciences, Education, and Human Science.[83]

A number of undergraduate academic programs at Florida State University are termed "Limited Access Programs". Limited Access Programs are programs where student demand exceeds available resources. Admission is thus restricted and sometimes extremely competitive. Examples of limited access programs include The Florida State University Film School, the College of Communication and Information, the College of Nursing, Computer Science, most of the majors in the College of Education, several majors in the College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance and all majors in the College of Business.[97]

Tuition

For the 2018–2019 academic year, tuition costs were:

- Undergraduate

- $215.55 per credit hour for in-state students, and $721.10 per credit hour for out-of-state students.[98] Total tuition/fees :$5,616 for in-state and $18,746 for out of state.[99]

- Graduate

- $479.32 per credit hour for in-state students, and $1,110.72 per credit hour for out-of-state students.[98] Total tuition/fees :$9,580 for in-state and $22,220 for out of state.[99]

- Law School

- $688.11 per credit hour for in-state students, and $1,355.18 per credit hour for out-of-state students.[98] Total tuition/fees :$20,644 for in-state and $40,656 for out of state.[100]

- Medical School

- $479.32 per credit hour for in-state students, and $1,110.72 per credit hour for out-of-state students.[98] Total tuition/fees per term :$8,536.86 (Cohort 1), $12,805.30 (Cohort 2), $8,492.86 (Cohort 3 & 4) for in-state students and $20,053.93 (Cohort 1), $30,080.90 (Cohort 2), $19,987.93 (Cohort 3 & 4) for out-of-state students.[101]

Admissions

| 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 78,088 | 65,256 | 63,691 | 58,936 | 50,314 | 35,334 |

| Admits | 19,552 | 24,184 | 20,668 | 21,202 | 18,504 | 17,381 |

| Enrolls | 6,033 | 7,619 | 6,009 | 7,106 | 6,324 | 6,523 |

| Admit rate | 25.0% | 37.1% | 32.5% | 36.0% | 36.8% | 49.2% |

| Yield rate | 30.9% | 31.5% | 29.1% | 33.5% | 34.2% | 37.5% |

| SAT composite* | 1220–1360 (68%†) | 1200–1330 (65%†) | 1230–1350 (65%†) | 1220–1330 (70%†) | 1200–1350 (65%†) | 1190–1330 (38%†) |

| ACT composite* | 26–31 (32%†) | 26–30 (35%†) | 27–31 (35%†) | 26–30 (30%†) | 26–30 (35%†) | 26–30 (62%†) |

| * middle 50% range † percentage of first-time freshmen who chose to submit | ||||||

The middle 50% of the Fall 2021 freshmen class had a GPA range from 4.1 – 4.5; a SAT total range from 1230 to 1360 and an ACT range from 27 – 31.[103] The acceptance rates for admission in 2020 were 32.4% and 27.9% respectively for 63,691 freshman applicants and less than 20,000 graduate school applicants.[104]

FSU's second-year, full-time freshman retention rate is 95.1%.[105] In 2019, the university achieved a four-year graduation rate of 72%, the highest rate in the State University System of Florida and among the top 10 nationally.[106] The university has over an 83.0% six-year graduation rate compared to the national average six-year graduation rate of 64%.[105][107]

Enrollment

| Academic Year | Undergraduates | Graduate | Total Enrollment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–2018 | 33,008 | 8,354 | 41,362 |

| 2018–2019 | 32,472 | 8,533 | 41,005 |

| 2019–2020 | 33,270 | 9,180 | 42,250 |

| 2020–2021 | 32,543 | 11,026 | 43,569 |

| 2021–2022 | 33,593 | 11,537 | 45,130 |

| 2022–2023 | 32,936 | 11,225 | 44,161 |

Florida State University students, numbering 45,493 in Fall 2021, come from more than 130 countries, and all 50 U.S. states.[8] The ratio of women to men is 57:43, and 22.6 percent are graduate and professional students.[8] Professional degree programs include Law, Medicine, Business Administration, Social Work, and Nursing.

| Race and ethnicity[108] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 59% | ||

| Hispanic | 22% | ||

| Black | 9% | ||

| Other[lower-alpha 1] | 5% | ||

| Asian | 3% | ||

| Foreign national | 1% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[lower-alpha 2] | 26% | ||

| Affluent[lower-alpha 3] | 74% | ||

In 2017, 7.1% of FSU students were international students. Of those, the most popular countries of origin were: China (20%), Panama 10.5%, India (6%), South Korea (5.4%), Colombia (5.1%), and Brazil (3.7%). In total, 2,974 international students enrolled at Florida State University.[109]

Miami-Dade, Broward, Palm Beach, Hillsborough, and Leon County make up the largest Florida counties for in-state students. The Miami metropolitan area accounts for the largest geographic origin of students and makes up 23.41% of the student body. Students from Georgia, Virginia, New York, New Jersey, North Carolina, Texas, Pennsylvania, and Maryland make up the largest states for out-of-state students.[110]

Rankings

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[111] | 67 |

| THE / WSJ[112] | 173 |

| U.S. News & World Report[113] | 55 |

| Washington Monthly[114] | 73 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[115] | 201–300 |

| QS[116] | 448 |

| THE[117] | 251–300 |

| U.S. News & World Report[118] | 190 |

|

USNWR graduate school rankings[119] | |

|---|---|

| Business | 85 |

| Education | 21 |

| Engineering | 92 |

| Law | 47 |

| Medicine: Primary Care | 78 |

| Medicine: Research | 93–123 |

| Nursing: Doctorate | 33 |

|

USNWR departmental rankings[119] | |

|---|---|

| Biological Sciences | 80 |

| Chemistry | 49 |

| Clinical Psychology | 27 |

| Computer Science | 82 |

| Criminology | 5 |

| Earth Sciences | 62 |

| Economics | 65 |

| English | 62 |

| Fine Arts | 42 |

| History | 81 |

| Library and Information Studies | 11 |

| Mathematics | 70 |

| Physics | 53 |

| Political Science | 41 |

| Psychology | 62 |

| Public Affairs | 46 |

| Public Health | 79 |

| Social Work | 42 |

| Sociology | 49 |

| Speech-Language Pathology | 20 |

| Statistics | 30 |

For 2022, U.S. News & World Report ranked Florida State University as the 19th best public university in the United States, and 55th overall among all national universities, public and private.[120]

For 2019, the FSU College of Business was ranked 27th undergraduate program among all public universities and 44th among all national universities.[121]

Florida State is ranked the 16th best doctorate-granting university in the US for the highest amount of African American doctorate recipients by the National Science Foundation.[122]

The FSU College of Medicine has been ranked among the nation's top 10 for Hispanic and Latino American students. In 2014, Hispanic Business ranked the med school eighth, the same as last year. The college was ranked seventh in 2012, seventh in 2009 and ninth in 2007. The magazine annually ranks colleges of business, engineering, law and medicine. Rankings are based on percentage of Hispanic student enrollment; percentage of Hispanic faculty members; percentage of degrees conferred upon Hispanics; and progressive programs aimed at increasing enrollment of Hispanic students.[123]

In 2012, the Princeton Review and USA Today ranked Florida State the fourth "Best Value" public university in the nation. In 2012, Florida State was ranked among universities as having the most financial resources per student.[124] Florida State is ranked the 29th top college in the United States by Payscale and CollegeNet's Social Mobility Index college rankings(2014).[125]

Florida State University is one of the two original state-designated "preeminent" universities in Florida.[126]

Florida State University receives the highest National Science Foundation research and development award in the state.[127]

Honors Program

Florida State University has a nationally recognized honors program.[128] The University Honors Office supports the university's long tradition of academic excellence by offering two programs, the University Honors Program and the Honors in the Major Program, which highlight the institution's strengths in teaching, research, and community service. The Honors Program also offers special scholarships, internships, research, and study abroad opportunities.

Admission into the University Honors Program is by invitation only. The average academic profile of students that were offered honors invitations in 2015 was as follows: 4.2 weighted GPA; 32 ACT composite; 2080 SAT total. For the Honors in the Major Program students, the University Honors Office requires that prospective students have at least sixty semester hours and at least a 3.2 cumulative FSU GPA.[129] The Honors program offers students housing in Landis Hall and Gilchrist Hall. Landis Hall is the traditional home of Honors students since 1955, which is situated on Landis Green at the heart of FSU's main campus. Gilchrist Hall also houses Honors students and is located adjacent to Landis Hall.

Honors scholarships

The Presidential Scholars Program is the premier undergraduate scholarship program at Florida State University. The program provides four years of support and is open to high school seniors who are admitted into Florida State University's Honors Program. The total award package for Presidential Scholars is $31,200, plus an out-of-state tuition waiver. This includes the $9,600 Presidential Scholarship distributed over four years and a $9,600 Admissions Scholarship distributed over four years. It also includes $12,000 for educational enrichment opportunities including international experiences such as Study Abroad and Global Scholars, research and creative projects, service learning projects or public service, internships, and entrepreneurial development. Support and guidance is offered through the Honors Program, Center for Undergraduate Research and Academic Engagement and the Office of National Fellows.[130]

International Programs

Florida State University's International Programs (FSU IP) is ranked 11th in the nation among university study abroad programs. Every year Florida State consistently sends over 2,379 students across the world to study in multiple locations.[131][132] As a student of IP, students are able to take classes that meet their major and/or minor requirements, study with experts in their field, and earn FSU credit.

Florida State has four permanent study centers providing residential and academic facilities in London; Florence, Italy; Valencia, Spain; and Panama City, Panama.[133]

Florida State University is well known for its undergraduate and graduate study abroad options: according to Uni in the USA, "the large numbers of students that study abroad nicely complement the students that study here from abroad."[134]

Career placement

The Florida State University Career Center is located in the Dunlap Success Center. Its mission is to provide comprehensive career services to students, alumni, employers, faculty/staff and other members of the FSU community. These services involve on and off-campus job interviews, career planning, assistance in applying to graduate and professional schools, internships, fellowships, co-op placements, research, and career portfolio resources.[135] The Career Center offers workshops, information sessions, and career fairs. Staff at the FSU Career Center advise students and alumni regarding resumes and portfolios, tactics for job interviews, cover letters, job strategies and other potential leads for finding employment in the corporate, academic, and government sectors.

The ProfessioNole program offers students the chance to reach out to professionals throughout the community, country, and world and learn more about their field's industry demands, career expectations, job outlook, and employment opportunities. Both alumni and friends of the university participate in ProfessioNole, making themselves available for student inquiries.[136] SeminoleLink is The Career Center's registration system linking students and alumni directly with employers. SeminoleLink is part of the NACElink Network, the largest network of career services and recruiting professionals in the world.[137]

Center for Academic Retention & Enhancement

The FSU Center for Academic Retention and Enhancement (CARE) provides preparation, orientation, and academic support programming for first-generation college students who are disadvantaged by economical and educational circumstances. CARE provides academic support services such as a dedicated tutoring and computer lab as well as advising and life coaching. It was created in 2000 after combining various minority academic programs, services, and scholarships into one entity which has enrolled over 5,500 students as of 2017.[138]

As of 2017, CARE had a first-year retention rate of 97 percent and had an 81 percent six-year graduation rate.[139] The average first term college GPA of CARE students throughout the inception of the program is 3.1.

The Summer Bridge Program (SBP) is an alternative admission program for disadvantaged first generation students.[140] The seven-week program helps students transition from high school by providing an early move-in date for easier acclimation, along with group activities managed by peer ambassadors who have already gone through the program.

The Unconquered Scholars Program provides additional support services for students who previously classified and experienced foster care, homelessness, relative care, or ward status.

Florida State University Libraries

The Florida State University Libraries house one of the largest collections of documents in the state of Florida. The Libraries' collections include over 3.75 million volumes, with a website offering access to more than 400 databases, 200,000 e-journals, and over 1.9 million e-books.[141] In total, Florida State has fifteen libraries and millions of books and journals to choose from. Eight libraries are located on the main Tallahassee campus, with the other seven located all over the world.[142] The collection covers virtually all disciplines and includes a wide array of formats – from books and journals to manuscripts, maps, and recorded music. Increasingly collections are digital and are accessible on the Internet via the library web page or the library catalog. The FSU Library System also maintains subscriptions to a vast number of online databases which can be accessed from any student account on or off campus.[143] The current dean of the Library System is Gale Etschmaier, who oversees a $19.9 million annual budget recorded in 2017.[141]

- Libraries

The Robert M. Strozier Library is Florida State's main library. It is located in the historic central area of the campus adjacent to Landis Green and occupies seven floors. Strozier's collections focus on Humanities, Social Sciences, Business, and Education. There has been a library at FSU since the 1880s, and the Main Library has been housed in several buildings. From 1911 to 1924, the Main Library was located in the Main Building, which is now Westcott. Dodd Hall was built as the first dedicated library building for the university, and the Main Library was housed there until the current building was built in 1956. The facility has been renovated several times. When opened, it consisted off three floors; an expansion in 1967 added five floors plus two subground floors to the rear of the original building.[144] In 2008, the lower floor reopened as the graduate- and faculty-focused Scholars Commons. In 2010, the main floor was transformed into an undergraduate-focused Learning Commons. The most recent renovation added smart study rooms, an enlarged computer area, new circulation areas, a tutoring center, and the nation's first double-sided Starbucks.[145] Strozier also houses the Special Collections and Archives division and Heritage Protocol. Strozier Library is open 24-hours on weekdays during the fall and spring semesters. The library closes early on Friday and Saturday nights and maintains decreased hours during the summer semester.[146]

The Paul A. M. Dirac Science Library is the main science library for Florida State University and houses over 500,000 books. Located on FSU's Legacy Walk farther west on campus, Dirac Library is smaller than Strozier at three stories. Dirac offers nearly 800 seats and provides 80 desktop computers (PC and Mac) and 80 laptop computers(PC and Mac) for use by students.[147] Dirac also offers 8 wireless Air Media Displays and 2 innovative MondoPad displays. There are over 35 individual and group study rooms that can be reserved online.[147] The library building is also home to the FSU School of Computational Science and Information Technology.[148] The library also houses a collection of materials principally related to Dirac's times at FSU and Cambridge University.[149] Dirac has been renovated in 2015 with new and improved amenities, technology, and seating.[147]

The Claude Pepper Center on campus is home to a think tank devoted to intercultural dialogue and the Mildred and Claude Pepper Library. It is located in what was originally the Florida State College for Women Library, which served as studios for WFSU-TV prior to construction of its current facility. The library contains a wide collection of documents, books, photographs, and recordings formerly belonging to Claude Pepper which are available to researchers. The center is also home to a collection of former Florida Governor Rubin Askew.[150] The center is headed by FSU alumnus Larry Polivka, PhD.[151] The goal of the Claude Pepper Center is to further the needs of elderly Americans and has worked towards this goal since it opened in 1998.[152]

The Warren D. Allen Music Library occupies 18,000 square feet of space within the Housewright Music Building in the Florida State University College of Music and serves as a repository for over 150,000 scores, sound recordings (17,000 albums and over 17,000 CDs), video recordings, books, periodicals, and microforms. The library was founded in 1911.[153]

The Harold Goldstein Library was a library on the main campus that housed a collection of approximately 82,000 books, videos and CDs relating to library and information science, information technology, and juvenile literature.[154][155] The largest part of the collection consisted of professional and reference materials as well as juvenile and easy books. In 2018, the Goldstein Library was replaced with the Innovation Hub, a technology hub, makerspace, and design-thinking center.[156] When the Goldstein Library closed, its collections were split and moved. The juvenile and library information titles were placed in the main library, Strozier, while the IT materials were moved to Dirac.[157] While Goldstein Library was a valuable library for FSU, its lack of a program-specific collection seems to have created an aimless library; its legacy for some, was a place to take great naps.[158][159]

The Florida State University College of Law Research Center houses the official library of the Florida State University College of Law. Located in B. K. Roberts Hall, the library has holdings consisting of over 500,000 volumes of which contain the basics of US law, English Common Law, and International law. The library also maintains subscriptions to several law-specific databases which can be accessed by students.[160]

In addition to the libraries located on the Tallahassee campus, FSU has five other libraries, museums, and research centers. These include the FSU Panama City, Florida Library and Learning Center, the FSU Panama, Republic of Panama Library, the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the FSU Florence, Italy Study Center, and the FSU London Study Center.[76]

Museums

The Ringling, the State Art Museum of Florida, is located in Sarasota, Florida and is administered by Florida State University[161] The museum was established in 1927. The institution offers twenty-one galleries of European paintings as well as Cypriot antiquities and Asian, American, and contemporary art. The museum's art collection currently consists of more than 10,000 objects that include a wide variety of paintings, sculpture, drawings, prints, photographs, and decorative arts from ancient through contemporary periods and from around the world. The most celebrated items are several Peter Paul Rubens paintings.[162] The Ringling Museum collections constitute the largest university museum complex in the United States.[163] In 2014 the Ringling was selected as the second most popular attraction in Florida by the readers of USAToday Travel.[164]

In all, more than 150,000 square feet (14,000 m2) have been added to the campus, which includes the art museum, circus museum, and Cà d'Zan, the Ringlings' mansion, which has been restored, along with the historic Asolo Theater. New additions to the campus include the Visitor's Pavilion, the Education, Library, and Conservation Complex, the Tibbals Learning Center complete with a miniature circus, and the Searing Wing, a 30,000-square-foot (2,800 m2) gallery for special exhibitions attached to the art museum.[165]

Florida State University also maintains the FSU Museum of Fine Arts (MoFA) on its Tallahassee campus. The MoFA permanent collection consists of over 4000 items in 18 sub-collections ranging from pre-Columbian pottery to contemporary art. The museum has a significant number of works of art on paper, including prints of artists as well known as Rembrandt and Pablo Picasso.[166]

Research

As one of the two primary research universities in Florida, Florida State University has long been associated with basic and advanced scientific research.[167] Today the university engages in many areas of academic inquiry at the undergraduate,[168] graduate[169] and postdoctoral levels.[170]

Florida State University was awarded $350.4 million in annual R&D expenditures, in sponsored research in fiscal year 2020,[15] ranking it 75th in the nation. FSU is one of the top 15 universities nationally receiving physical sciences funding from the National Science Foundation.[171]

Florida State currently has 19 graduate degree programs in interdisciplinary research fields.[172] Interdisciplinary programs merge disciplines into common areas where discoveries may be exploited by more than one method. Interdisciplinary research at FSU covers traditional subjects like chemistry, physics and engineering to social sciences.

National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

The National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL) or "Mag Lab" at Florida State develops and operates high magnetic field facilities that scientists use for research in physics, biology, bioengineering, chemistry, geochemistry, biochemistry, materials science, and engineering. It is the only facility of its kind in the United States and one of only nine in the world. Fourteen world records have been set at the Mag Lab to date.[173] The Magnetic Field Laboratory is a 440,000 sq. ft (40,877 square meter) complex employing 507 faculty, staff, graduate, and postdoctoral students. This facility is the largest and highest powered laboratory of its kind in the world and produces the highest continuous magnetic fields.

MIT Contest of lab award

In 1990 the National Science Foundation awarded Florida State University the right to host the new National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. Rather than improve the existing Francis Bitter Magnet Laboratory controlled by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) together with a consortium of other universities, the NSF elected to move the Lab mainly to Florida State University, with a smaller facility at the University of Florida.[173] The award of the laboratory was contested by MIT in an unprecedented request to the NSF for a review of the award.[174] The NSF denied the appeal, explaining that the superior enthusiasm for and commitment to the project demonstrated by Florida State led to the decision to relocate the lab.[175]

Large Hadron Collider

After decades of planning and construction the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) is a next generation detector for the new proton-proton collider (7 TeV + 7 TeV) called the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) which is now operational in the existing 17 mi (27 km) circular tunnel near Geneva, Switzerland at CERN, the European Laboratory for Particle Physics. Florida State University faculty members collaborated in the design, construction and operation of the LHC, with some components assembled at Florida State and shipped to CERN for installation.[176] Florida State faculty contributed to several areas of the CMS, especially the electromagnetic calorimeter and the hadron calorimeter.[177]

High-Performance Materials Institute

The High-Performance Materials Institute (HPMI) is a multidisciplinary research institute at Florida State University. Currently, HPMI is involved in four primary technology areas: High-Performance Composite and Nanomaterials, Structural Health Monitoring, Multifunctional Nanomaterials Advanced Manufacturing and Process Modeling.

Over the last several years, HPMI has proven a number of technology concepts that have the potential to narrow the gap between research and practical applications of nanotube-based materials. These technologies include magnetic alignment of nanotubes, fabrication of nanotube membranes or buckypapers, production of nanotube composites, modeling of nanotube-epoxy interaction at the molecular level, and characterization of SWNT nanocomposites for mechanical properties, electrical conductivity, thermal management, radiation shielding and EMI attenuation. HPMI personnel also established Florida's first National Science Foundation (NSF) Industry/University Cooperative Research Center (IUCRC).

In 2006, the Florida Board of Governors designated HPMI as a Center of Excellence in Advanced Materials and awarded $4 million to further HPMI's efforts in technology transfer, economic development and work force training. Under its cluster hiring program, FSU has awarded the HPMI team with an additional $4 million to recruit and hire some of the nation's top researchers in Materials. HPMI personnel moved into the new $20 million, 45,000 square foot Materials Research Building, which houses equipment and facilities for materials research, especially designed for research in nanomaterials.[178]

The Center for Advanced Power Systems

Florida State University's Center for Advanced Power Systems (CAPS) has become the first university test site accredited by the U.S. Navy to perform high-powered simulations as the center develops next-generation shipboard power technology.

The Center for Advanced Power Systems is a multidisciplinary research center organized to perform basic and applied research to advance the field of power systems technology. CAPS' emphasis is on application to electric utility, defense, and transportation, as well as, developing an education program to train the next generation of power systems engineers. The research focuses on electric power systems modeling and simulation, power electronics and machines, control systems, thermal management, cyber-security for power systems, high temperature superconductor characterization and electrical insulation research. With support from the U.S. Navy, Office of Naval Research (ONR) and the U.S. Department of Energy, CAPS has established a unique test and demonstration facility with one of the largest real-time digital power systems simulators along with 5 MW AC and DC test beds for hardware in the loop simulation. The center is supported by a research team composed of researchers, scientists, faculty, engineers, and students, recruited from across the globe, with strong representation from both the academic/research community and industry.[179]

In January 2015, Florida State University's Center for Advanced Power Systems has unveiled a new 24,000-volt direct current power test system, the most powerful of its kind available at a university research center throughout the world. The new test facility is the latest piece of the center's PHIL testing program. It has a 24,000-volt direct current with a capacity of 5 megawatts, making it the most powerful PHIL system of its kind at a university research center worldwide. To create the new system, the center put together four individual 6 kilovolt, 1.25 megawatt converters that can be arranged in any combination, in series or parallel connection, to form an extremely flexible test bed for medium voltage direct current (MVDC) system investigations.[180]

CAPS researchers are also collaborating with Virginia Tech on a project for the U.S. Office of Naval Research to evaluate the performance of an electrical impedance measurement unit (IMU) developed by Virginia Tech and to be shipped to CAPS for testing. The purpose of an IMU is to probe a power system for its impedance characteristics to establish criteria for stable operation of the system.

CAPS is a long-term contractor with the U.S. Navy, which is working to develop an all-electric ship. The Navy has also committed funding to study design and performance of fault current limited MVDC systems and other operational aspects of MVDC systems.

Coastal and Marine Laboratory

The FSU Coastal and Marine Laboratory is located about 45 miles (72 km) from the main campus in Tallahassee. It is on the coast of St. Teresa, Florida, between Panacea and Carrabelle, on Apalachee Bay, 8 acres (32,000 m2) of which is right on the water and the remaining 70 acres (280,000 m2) of which is directly across the road. The mission of the FSUCML is to conduct innovative, interdisciplinary research focused on the coastal and marine ecosystems of the northeastern Gulf of Mexico, with a focus on solving the ecological problems faced by the region by providing the scientific underpinnings for informed policy decisions. Research is conducted by faculty in residence and by those from the main campus, as well as by faculty, postdoctoral, graduate, and undergraduate investigators from FSU and other universities throughout the world.[181]

Florida State University established its first marine laboratory, the Oceanographic Institute, in 1949, on 25 acres (100,000 m2) on the harbor side of the peninsula that forms Alligator Harbor, which maintained a substantial research effort throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Other marine stations maintained by Florida State University until 1954 included one at Mayport, on the St. Johns River near Jacksonville, which conducted research related to the menhaden and shrimp fisheries and oceanographic problems of the Gulf Stream and the mouth of the St. John's River, and one on Mullet Key at the mouth of Tampa Bay, which studied red tide.

In the late 1960s, FSU moved the lab to its current location west of Turkey Point, on land donated by Edward Ball, the founder of the St. Joe Paper Company, and changed its name to The Edward Ball Marine Laboratory. In 2006, the lab became known as The Florida State University Coastal and Marine Laboratory (FSUCML), a name that better reflects the expanded programmatic base of its research, education, and outreach missions.[182]

Student life

Traditions

The university's colors are garnet and gold.[183] The colors of garnet and gold represent a merging of the university's past. While the school fielded a football team as early, or earlier than 1899,[184] in 1902, 1903 and 1905 the team won football championships wearing purple and gold uniforms.[22][185] The following year, the college student body selected crimson as the official school color. The administration in 1905 took crimson and combined it with the recognizable purple of the championship football teams to achieve the color garnet. After World War II the garnet and gold colors were first worn by a renewed football team in a 14–6 loss to Stetson University on October 18, 1947. Florida State University's marching band is the Marching Chiefs.

Alma mater

The alma mater for Florida State University was composed by Charlie Carter in 1956.[186]

The most popular songs of Florida State University include:

- Alma Mater – "High O'er Towering Pines"

- Hymn – "Hymn To the Garnet and Gold"

- Fight Song – "FSU Fight Song"

Residential life

Florida State University provides 6,733 undergraduate and graduate students with housing as well as living–Learning Communities (LLC) on the main campus. This number will soon be expanded to 7,283 with new housing projects.[187] Florida State University is a traditional residential university wherein most students live on campus in university residence halls or nearby in privately owned residence halls, apartments and residences.

Student clubs and activities

Florida State University has more than 750 Recognized Student Organizations (RSOs) for students to join.[188] They range from cultural and athletic to philanthropy, including Phi Beta Kappa, AcaBelles, Garnet and Gold Scholar Society, Marching Chiefs, Garnet Girls Competitive Cheerleading, Florida State Golden Girls, FSU Pow Wow, FSU Majorettes, Hillel at FSU, Seminole Flying Club, No Bears Allowed, FSU Student Foundation, InternatioNole, Student Alumni Association, Hispanic/Latino Student Union, Relay For Life, The Big Event at FSU, Por Colombia, Quidditch at FSU, and the Men's Soccer Club. All organizations are funded through the SGA and many put on events throughout the year. Students may create their own RSO if the current interest or concern is not addressed by the previously established entities.[188]

Fitness and intramural sports

The Bobby E. Leach Student Recreation Center is a 120,000 square foot fitness facility located right in the heart of campus. Construction on the center was completed in 1991.[189] The Leach Center has three regulation-size basketball courts on the upper level with the third court being designated for other sports such as volleyball, table tennis, and badminton. It also has five racquetball & squash courts for recreational matches and an indoor track overlooking the pool on the third level of the facility.

The Leach Pool is a 16-lane by 25-yard indoor swimming facility with two 1-meter and two 3-meter diving boards.[190]

Florida State University also has an intramural sports program.[191] Sports clubs include equestrian and water sailing. The clubs compete against other Intercollegiate club teams around the country. Intramural sports include flag football, basketball, recreational soccer, volleyball, sand volleyball, softball, swimming, kickball, mini golf, team bowling, tennis, ultimate frisbee, wiffle ball, dodge ball, battleship, college pick em, innertube water polo, kan jam, spikeball, and wallyball.[192]

A new area of intramural sports fields, named the 104-acre (0.4 km2) RecSports Plex, was opened in September 2007 on Tyson Road, southwest of the stadium.[193][194] This intramural sports complex is the largest in the nation with twelve football/soccer fields, five softball fields, four soccer fields, and basketball and volleyball courts.[193]

Entertainment

A large amount of student life is centered around the FSU Student Union, located on the North side of campus. The Union was originally constructed in 1952 and expanded in 1964.[195] In 2018, renovations of the formerly named Oglesby Union began.[196] The old Union building was demolished that summer and buildings for the renovated Union were completed in the summer of 2022 after a turbulent construction period.[197][198] During construction, the services that were housed in the Union were moved to temporary locations around campus. Crenshaw Lanes is a twelve lane bowling alley located in the FSU Student Union and it includes ten full sized billiard tables. It has been at FSU since 1964. The Crenshaw Lanes were temporarily closed during construction of the renovated Union, but opened along with the new establishment as "Bowling and Billiards".[199]

Club Downunder hosts entertainment acts such as bands and comedians.[200] Past bands that have come through Club Downunder include The White Stripes, Modest Mouse, The National, Girl Talk, Spoon, Soundgarden, She Wants Revenge, Cold War Kids, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and Death Cab for Cutie. All shows that take place at Club Downunder are free for FSU students.[200]

The Askew Student Life Center is home to the Student Life Cinema and various cafes.[201]

Florida State's Reservation is a 73-acre (300,000 m2) lakeside recreational area located off campus.[202] This university retreat on Lake Bradford was founded in 1920 as a retreat for students when FSU was the state college for women between 1905 and 1947. The original name for the retreat was Camp Flastacowo.[203]

Florida State University is one of two collegiate schools in the country that has a circus.[204] The FSU Flying High Circus, founded in 1947, counts as an extracurricular activity under.[205]

A Cappella Groups

Florida State University is home to five student-run a cappella groups: Acaphiliacs (mixed), All-Night Yahtzee (mixed), Vox (mixed), AcaBelles (treble), and Reverb (tenor/bass). All five groups regularly compete in the International Championship of Collegiate A Cappella (ICCA). All-Night Yahtzee is one of only three groups in the world to compete at ICCA finals in New York City five times, and they placed second at the competition in 2008. The AcaBelles competed at ICCA finals in 2009 and 2011, and Reverb placed fourth in their only bid to ICCA finals in 2013.[206] In 2020, The A Cappella Archive ranked All-Night Yahtzee at #4 among all ICCA-competing groups.[207]

Greek life

About 14% of undergraduate men are in a fraternity and 23% of undergraduate women are in a sorority.[208][209] The Office of Greek Life at Florida State University encompasses the Interfraternity Council (IFC), Panhellenic Council (NPC), Multicultural Greek Council (MGC), and the National Pan-Hellenic Council (NPHC). The Order of Omega and Rho Lambda Honor Societies also have chapters at Florida State.

In 2017, university president John E. Thrasher suspended activities at all of the university's 55 fraternities and sororities, days after two unrelated incidents in which a 20-year-old fraternity pledge died following a party at an off-campus house and a 20-year-old fraternity member was arrested on charges of cocaine trafficking. Thrasher said that Greek activities would be permitted to resume after the university developed new policies, saying "The message is not getting through" and calling for a major culture shift.[210][211]

Reserve Officer Training Corps

Florida State University's Reserve Officer Training Corps is the official officer training and commissioning program at Florida State University. Dating back to Civil War days, the ROTC unit at Florida State University is one of four collegiate military units with permission to display a battle streamer, in recognition of the military service of student cadets during the Battle of Natural Bridge in 1865.[212]

The Reserve Officer Training Corps offers commissions for the United States Army and the United States Air Force. The Reserve Officer Training Corps at Florida State is currently located at the Harpe-Johnson Building.[213]

The Reserve Officer Training Corps at Florida State University offers training in the military and aerospace sciences to students who desire to perform military service after they graduate. The Departments of the Army and Air Force each maintain a Reserve Officers Training Corps and each individual department (Department of Military Studies for the Army; Department of Aerospace Studies for the Air Force) has a full staff of active duty military personnel serving as instructor cadre or administrative support staff. Florida State University is also a cross-town affiliate with Florida A&M University's Navy ROTC Battalion, allowing FSU students to pursue training in the naval sciences for subsequent commissioning as officers in the Navy or Marine Corps.[214]

Campus and area transportation

The FSU campus is served by eight bus routes of the Seminole Express Bus Service. The Seminole Express Bus Service provides transportation to, around, and from campus to the surrounding Tallahassee areas for Faculty, Staff, Students and Visitors. All students, faculty and staff can also ride any StarMetro bus throughout the City of Tallahassee for free by swiping a valid FSUCard.[215] FSU also provides other campus services, including Spirit Shuttle (during football games), Nole Cab, S.A.F.E. Connection, and Night Nole nighttime service.[216]

Florida State University is also served by the Tallahassee International Airport, which is located in the Southwest portion of Tallahassee and has daily services to Miami, Fort Lauderdale, Orlando, Tampa, Atlanta, Charlotte, and Dallas–Fort Worth.[217]

Student media

The campus newspaper, the FSView & Florida Flambeau, is 100 years old now and publishes weekly during the summer and semiweekly on Mondays and Thursdays during the school year following the academic calendar. After changing hands three times in 13 years, the FSView was sold to the Tallahassee Democrat in late July 2006, making it part of the Gannett chain.[218]

FSU operates two television stations, WFSU and WFSG,[219] and three radio stations, WFSU-FM, WFSQ-FM and WFSW-FM.[220] FSU operates a fourth radio station, WVFS (V89, "The Voice", or "The Voice of Florida State"), as an on-campus instructional radio station staffed by student and community volunteers.[221] WVFS broadcasts primarily independent music as an alternative to regular radio.

The English Department publishes a literary journal, The Southeast Review, founded in 1979 as Sundog.[222]

Athletics

The school's athletic teams are called the Seminoles, derived from the Seminole people. The name was chosen by students in 1947 and is officially sanctioned by the Seminole Tribe of Florida;[223] the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma has taken no official position regarding the university's use of the name.[224] Florida State's athletes participate in the NCAA's Division I (Bowl Subdivision for football) and in the Atlantic Coast Conference.

For the 2017–2018 school year, the Florida State Athletics Department budgeted $103.2 million for its sports teams and facilities and currently brings in over $121.3 million in revenues.[225][226] Florida State University is known for its competitive athletics in both men's and women's sports competitions. The men's program consists of baseball, basketball, cross country running, football, golf, swimming, tennis, and track & field. The women's program consists of basketball, cross country running, golf, soccer, softball, swimming, tennis, track & field, and volleyball. FSU's Intercollegiate Club sports include bowling, crew, rugby, soccer and lacrosse.[227]

There are two major stadiums and an arena within FSU's main campus: Doak Campbell Stadium for football, Dick Howser Stadium for men's baseball, and the Donald L. Tucker Center for men's and women's basketball. The Mike Long Track is the home of the national champion men's outdoor track and field team.[228] H. Donald Loucks courts at the Speicher Tennis Center is the home of the FSU tennis team. By presidential directive the complex was named in honor of Lieutenant Commander Michael Scott Speicher, a graduate of Florida State University and the first American casualty during Operation Desert Storm.[229][230] The Seminole Soccer Complex is home to women's soccer. It normally holds a capacity of 1,600 people but has seen crowds in excess of 4,500 for certain games. The home record is 4,582 for the 2006 game versus the University of Florida.[231] The FSU women's softball team plays at the Seminole Softball Complex; the field is named for JoAnne Graf, the winningest coach in softball history.[232]

Florida State University has been penalized seven times by the NCAA for major infractions for the period 1968 through 2009.[233] These infractions range from improper recruiting of student-athletes, failure to investigate adequately to academic fraud.

Seminole baseball

Seminole baseball is one of the most successful collegiate baseball programs in the United States having been to 20 College World Series', and having appeared in the national championship final on three occasions (falling to the university of Southern California Trojans in 1970, the university of Arizona Wildcats in 1986, and the university of Miami Hurricanes in 1999).[234] Under the direction of Head Coach No. 11 Mike Martin (FSU 1966), Florida State is the second-winningest program in the history of college baseball.[234] Since 1990, FSU has had more 50 win seasons, headed to more NCAA Tournaments (19 Regional Tournaments in 20 years), and finished in the top 10 more than any team in the United States.[234] Since 2000, FSU is the winningest program in college baseball with more victories and a higher winning percentage in the regular season than any other school.[234]

Seminole football

The Florida State Seminoles football program has played in 49 bowl games, won three consensus national championships, eighteen Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) championships, six ACC division titles, produced 218 All-Americans, 47 National Football League (NFL) first-round draft choices, and three Heisman Trophy winners. The Seminoles have achieved three undefeated seasons and finished ranked in the top five of the AP Poll for 14 straight years from 1987 through 2000. The Florida State Seminoles are one of the 120 NCAA Division I FBS collegiate football teams in America.

The Seminoles' home field is Bobby Bowden Field at Doak Campbell Stadium, which has a capacity of 79,560.[235]

Florida State University fielded its first official varsity football team in the fall of 1902 until 1904, which were then known as "The Eleven".[184][236] The team went (7–6–1) over the 1902–1904 seasons posting a record of (3–1) against their rivals from the Florida Agricultural College in Lake City. In 1904 the Florida State football team became the first ever state champions of Florida after beating both the Florida Agricultural College and Stetson University.[236]

Under head coach Bobby Bowden, the Seminole football team became one of the nation's most competitive college football teams.[237] The Seminoles played in five national championship games between 1993 and 2001 and won the championship in 1993 and 1999. The FSU football team was the most successful team in college football during the 1990s, boasting an 89% winning percentage.[238] Bobby Bowden would retire with the record for most all-time career wins in Division I football.[239] Jimbo Fisher succeeded Bowden as head coach in 2010, winning a national championship in 2013 before departing to join Texas A&M after the 2017 season. The current head coach is Mike Norvell. FSU football has introduced a number of successful players into the NFL, including Deion Sanders, Derrick Brooks, LeRoy Butler, and Jameis Winston.

Seminole track and field

The FSU men's Track & Field team won the Atlantic Coast Conference championship four times running, in addition to winning the NCAA National Championship three consecutive years.[228][240][241][242] In 2006 Head Coach Bob Braman and Associate Head Coach Harlis Meaders helped lead individual champions in the 200 m (Walter Dix), the triple jump (Raqeef Curry), and the shot put (Garrett Johnson). Individual runners-up were Walter Dix in the 100 m, Ricardo Chambers in the 400 m, and Tom Lancashire in the 1500 m. Others scoring points in the National Championship were Michael Ray Garvin in the 200 m (8th), Andrew Lemoncello in the 3000 m steeplechase (4th), Raqeef Curry in the long jump (6th), and Garrett Johnson in the discus (5th).[243] In 2007, FSU won its second straight men's Track & Field NCAA National Championship when Dix became the first person to hold the individual title in the 100 m, 200 m, and 400 m at the same time.[244]

Faculty