Leon County, Florida

Leon County (Spanish: Condado de León) is a county in the Panhandle of the U.S. state of Florida. It was named after the Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León. As of the 2020 census, the population was 292,198.[1][2]

Leon County | |

|---|---|

.JPG.webp) Leon County Courthouse | |

Flag  Seal | |

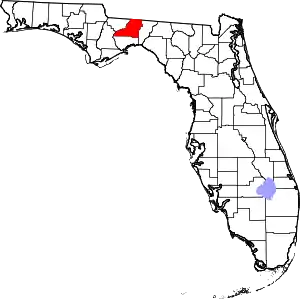

Location within the U.S. state of Florida | |

Florida's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 30°28′N 84°17′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | December 29, 1824 |

| Named for | Juan Ponce de León |

| Seat | Tallahassee |

| Largest city | Tallahassee |

| Area | |

| • Total | 702 sq mi (1,820 km2) |

| • Land | 667 sq mi (1,730 km2) |

| • Water | 35 sq mi (90 km2) 5.0% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 292,198 |

| • Density | 420/sq mi (160/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 2nd |

| Website | www |

The county seat is Tallahassee,[3] which is also the state capital and home to many politicians, lobbyists, jurists, and attorneys.

Leon County is included in the Tallahassee metropolitan area. Tallahassee is home to two of Florida's major public universities, Florida State University and Florida A&M University, as well as Tallahassee Community College. Together these institutions have a combined enrollment of more than 70,000 students annually, creating both economic and social effects.

History

Originally part of Escambia and later Gadsden County, Leon County was created in 1824.[4] It was named after Juan Ponce de León, the Spanish explorer who was the first European to reach Florida.[5]

The United States finally acquired this territory in the 19th century. In the 1830s, it attempted to conduct Indian Removal of the Seminole and Creek peoples, who had migrated south to escape European-American encroachment in Georgia and Alabama. After many Seminole were forcibly removed from the area or moved south to the Everglades during the Seminole Wars, planters developed cotton plantations based on enslaved labor.

By the 1850s and 1860s, Leon County had become part of the Deep South's "cotton kingdom". It ranked fifth of all Florida and Georgia counties in cotton production from the 20 major plantations. Uniquely among Confederate capitals east of the Mississippi River, in the American Civil War Tallahassee was never captured by Union forces. No Union soldiers set foot in Leon County until the Reconstruction Era.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has an area of 702 square miles (1,820 km2), of which 667 square miles (1,730 km2) are land and 35 square miles (91 km2) (5.0%) are water.[6] Unlike much of Florida, most of Leon County has rolling hills, as part of Florida's Red Hills Region. The highest point is 280 feet (85 m), in the northern part of the county.

Geology

Leon County encompasses basement rock composed of basalts of the Triassic and Jurassic from ~251 to 145 million years ago interlayered with Mesozoic sedimentary rocks. The layers above the basement are carbonate rock created from dying foraminifera, bryozoa, mollusks, and corals from as early as the Paleocene, a period of ~66—55.8 Ma.[7]

During the Eocene (~55.8—33.9 Ma) and Oligocene (~33.9—23 Ma), the Appalachian Mountains began to uplift and the erosion rate increased enough to fill the Gulf Trough with quartz sands, silts, and clays via rivers and streams. The first sedimentation layer in Leon County is the Oligocene Suwannee Limestone in the southeastern part of the county as stated by the United States Geological Survey and Florida Geological Survey.[8]

The Early Miocene (~23.03—15.7 Ma) sedimentation in Leon County is Hawthorn Group, Torreya Formation and St. Marks Formation and is found in the northern two-thirds of the county.

The Pliocene (~5.332—2.588 Ma) is represented by the Miccosukee Formation scattered within the Torreya Formation.

Sediments were laid down from the Pleistocene epoch (~2.588 million—12 000 years ago) through the Holocene epoch (~12,000—present) and are designated Beach ridge and trail and undifferentiated sediments.

Terraces and shorelines

During the Pleistocene, what would be Leon County emerged and submerged with each glacial and interglacial period. Interglacials created the county's topography.

Also See Leon County Pleistocene coastal terraces

Also see: Florida Platform and Lithostratigraphy

Geologic formations

- Red Hills Region (North)

- Cody Scarp (central)

- Woodville Karst Plain (South)

Paleontology

Three sites in Leon County have yielded fossil remnants of the Miocene epoch.

National protected area

- Apalachicola National Forest (part)

Bodies of water

- Lake Miccosukee

- Black Creek

- Lake Bradford

- Lake Ella

- Lake Hall

- Lake Iamonia

- Lake Jackson

- Lake Lafayette

- Lake Talquin

- Ochlockonee River

- Lake Munson

Adjacent counties

- Grady County, Georgia - north

- Thomas County, Georgia - northeast

- Jefferson County - east

- Wakulla County - south

- Gadsden County - west

- Liberty County - west

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1830 | 6,494 | — | |

| 1840 | 10,713 | 65.0% | |

| 1850 | 11,442 | 6.8% | |

| 1860 | 12,343 | 7.9% | |

| 1870 | 15,236 | 23.4% | |

| 1880 | 19,662 | 29.0% | |

| 1890 | 17,752 | −9.7% | |

| 1900 | 19,887 | 12.0% | |

| 1910 | 19,427 | −2.3% | |

| 1920 | 18,059 | −7.0% | |

| 1930 | 23,476 | 30.0% | |

| 1940 | 31,646 | 34.8% | |

| 1950 | 51,590 | 63.0% | |

| 1960 | 74,225 | 43.9% | |

| 1970 | 103,047 | 38.8% | |

| 1980 | 148,655 | 44.3% | |

| 1990 | 192,493 | 29.5% | |

| 2000 | 239,452 | 24.4% | |

| 2010 | 275,487 | 15.0% | |

| 2020 | 292,198 | 6.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[9] 1790-1960[10] 1900-1990[11] 1990-2000[12] 2010-2019[1] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Pop 2010 | Pop 2020 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 163,483 | 157,458 | 59.34% | 53.89% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 82,386 | 87,503 | 29.91% | 29.95% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 681 | 631 | 0.25% | 0.22% |

| Asian (NH) | 7,950 | 10,465 | 2.89% | 3.58% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 121 | 155 | 0.04% | 0.05% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 511 | 1,261 | 0.19% | 0.43% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 4,994 | 11,811 | 1.81% | 4.04% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 15,361 | 22,914 | 5.58% | 7.84% |

| Total | 275,487 | 292,198 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 292,198 people, 116,530 households, and 61,961 families residing in the county.

Race

As of the census[17] of 2010, there were 275,487 people, and 108,592 households residing in the county. The population density was 413.2 inhabitants per square mile (159.5/km2). There were 123,423 housing units at an average density of 185 per square mile (71/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 63.0% White, 30.3% Black or African American, 0.3% Native American, 2.9% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, and 2.2% from two or more races. 5.6% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

Age

There were 108,592 households, out of which 24.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.9% were married couples living together, 13.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.8% were non-families. 31.0% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.92.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 20.0% under the age of 18, 26.3% from 18 to 24, 22.7% from 25 to 44, 22.4% from 45 to 64, and 8.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.57 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.03 males.

Education

At 70.2%, Leon County enjoys the highest level of post-secondary education in the state of Florida, followed by Alachua County with a total of 67.8%.

| Level of Education | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | Leon Co. | Florida | U.S. | |

|

| ||||

| Some college or associate degree | 28.5% | 28.8% | 27.4% | |

| Bachelor's Degree | 24.0% | 14.3% | 15.5% | |

| Master's or Ph.D. | 17.7% | 8.1% | 8.9% | |

| Total | 70.2% | 51.2% | 51.8% | |

Source of above:[18]

Income

The median income for a household in the county was $37,517, and the median income for a family was $52,962. Males had a median income of $35,235 versus $28,110 for females. The per capita income for the county was $21,024. About 9.40% of families and 18.20% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.20% of those under age 18 and 8.20% of those age 65 or over.

Accolades

- 2007 National Association of County Park and Recreation Officials' Environmental and Conservation Award for exceptional effort to reclaim, restore, preserve, acquire or develop unique and natural areas. Leon County has 1,300 acres (5.3 km2) of open space, forest and woodlands between the Miccosukee Canopy Road Greenway and J.R. Alford Greenway.

Law, government, and politics

Politics

Leon County is governed by an elected seven-member board of county commissioners.

Following Reconstruction, white Democrats regained power in Leon County and voters have historically voted for Democratic candidates at the national level. Tallahassee is one of the few cities in the South known for progressive activism.

The county has voted Democratic in 24 of the past 29 presidential elections since 1904. (Until the late 1960s, blacks were essentially disenfranchised in Florida and other Southern states.) Since the civil rights era, Tallahassee has elected black mayors and black state representatives.[19] Its political affiliations likely draw from the high number of students, staff, and faculty associated with Florida State University, Florida A&M University, and Tallahassee Community College in Tallahassee, as well as the concentration of government employees.

Leon County has had the highest voter turnout of any Florida county. In the 2008 general election, it had a record-setting voter turnout of 85%, including early voting and voting by mail.[20]

As of October 6, 2020, there were 116,294 Democrats, 57,791 Republicans, and 43,369 voters with other affiliations in Leon County.[21]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 57,453 | 35.14% | 103,517 | 63.32% | 2,506 | 1.53% |

| 2016 | 53,821 | 34.98% | 92,068 | 59.83% | 7,992 | 5.19% |

| 2012 | 55,805 | 37.54% | 90,881 | 61.13% | 1,985 | 1.34% |

| 2008 | 55,705 | 37.40% | 91,747 | 61.60% | 1,483 | 1.00% |

| 2004 | 51,615 | 37.85% | 83,873 | 61.50% | 891 | 0.65% |

| 2000 | 39,073 | 37.88% | 61,444 | 59.57% | 2,637 | 2.56% |

| 1996 | 33,930 | 36.99% | 50,072 | 54.59% | 7,715 | 8.41% |

| 1992 | 31,983 | 32.87% | 47,791 | 49.12% | 17,520 | 18.01% |

| 1988 | 36,055 | 51.39% | 33,472 | 47.71% | 631 | 0.90% |

| 1984 | 36,325 | 55.00% | 29,683 | 44.94% | 38 | 0.06% |

| 1980 | 24,919 | 43.47% | 28,450 | 49.63% | 3,957 | 6.90% |

| 1976 | 23,739 | 44.42% | 28,729 | 53.76% | 975 | 1.82% |

| 1972 | 27,479 | 63.72% | 15,555 | 36.07% | 92 | 0.21% |

| 1968 | 9,288 | 28.49% | 10,440 | 32.02% | 12,878 | 39.50% |

| 1964 | 15,181 | 58.15% | 10,927 | 41.85% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 9,079 | 46.53% | 10,433 | 53.47% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 6,828 | 49.30% | 7,022 | 50.70% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 5,604 | 41.19% | 8,000 | 58.81% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 1,149 | 18.65% | 3,607 | 58.55% | 1,405 | 22.80% |

| 1944 | 835 | 15.64% | 4,505 | 84.36% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 583 | 9.65% | 5,459 | 90.35% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 277 | 6.84% | 3,770 | 93.16% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1932 | 252 | 7.87% | 2,950 | 92.13% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1928 | 630 | 24.72% | 1,888 | 74.07% | 31 | 1.22% |

| 1924 | 92 | 8.29% | 947 | 85.32% | 71 | 6.40% |

| 1920 | 452 | 22.97% | 1,412 | 71.75% | 104 | 5.28% |

| 1916 | 191 | 16.32% | 875 | 74.79% | 104 | 8.89% |

| 1912 | 56 | 8.41% | 546 | 81.98% | 64 | 9.61% |

| 1908 | 143 | 14.93% | 698 | 72.86% | 117 | 12.21% |

| 1904 | 84 | 11.37% | 649 | 87.82% | 6 | 0.81% |

| 1900 | 162 | 13.95% | 932 | 80.28% | 67 | 5.77% |

| 1896 | 247 | 15.52% | 1,298 | 81.53% | 47 | 2.95% |

| 1892 | 0 | 0.00% | 634 | 100.00% | 0 | 0.00% |

County representation

| Leon County Government | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Position | Name | Party | |

|

| |||

| Commissioner, At-Large | Nicholas J. Maddox | Democratic | |

| Commissioner, At-Large | Carolyn D. Cummings | Democratic | |

| Commissioner, Dist. 1 | William C. Proctor | Democratic | |

| Commissioner, Dist. 2 | Christian Caban | Democratic | |

| Commissioner, Dist. 3 | W. Richard Minor | Democratic | |

| Commissioner, Dist. 4 | G. Brian Welch | Democratic | |

| Commissioner, Dist. 5 | David O'Keefe | Democratic | |

| Supervisor of Elections | Mark Earley | NPA | |

| Tax Collector | Doris Maloy | Democratic | |

| Property Appraiser | Akin Akinyemi | Democratic | |

| Court Clerk | Gwendolyn M. Marshall | Democratic | |

| Sheriff | Walt McNeil | Democratic | |

| School Superintendent | James P. "Rocky" Hanna | Democratic | |

State representation

Allison Tant (D), District 9, represents Leon County's northern half, including most of Tallahassee. Jason Shoaf (R), District 7, represents the county's southern portion. He won office in a special election.[23] Gallop Franklin (D), District 8, represents a west-central portion of the county.

State senator

All of Leon County is represented by Corey Simon (R), District 3, in the Florida Senate.

U.S. Congressional representation

Leon County is located in the 2nd congressional district after the 2020 census redistricting process was completed. It is currently represented by Neal Dunn (R).

Consolidation

Leon County voters have gone to the polls four times to vote on consolidation of the Tallahassee and Leon County governments into one jurisdiction.[24] This proposal would combine police and other city services with the already shared (consolidated) Tallahassee Fire Department, Tallahassee/Leon County Planning Department, and Leon County Emergency Medical Services. Tallahassee's city limits would (at current size) increase from 98.2 square miles (254 km2) to 702 square miles (1,820 km2). Roughly 36 percent of Leon County's 250,000 residents live outside the Tallahassee city limits.

| Leon County Voting On Consolidation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | FOR | AGAINST | |||||

|

| |||||||

| 1971 | 10,381 (41.32%) | 14,740 (58.68%) | |||||

| 1973 | 11,056 (46.23%) | 12,859 (53.77%) | |||||

| 1976 | 20,336 (45.01%) | 24,855 (54.99%) | |||||

| 1992 | 37,062 (39.8%) | 56,070 (60.2%) | |||||

Proponents of consolidation have claimed that the new jurisdiction would attract business by its very size. Merging of governments would cut government waste, duplication of services, etc. Professor Richard Feiock of Florida State University found in a 2007 study that he could not conclude that consolidation would benefit the local economy.[25]

Public services

Leon County Sheriff

The Leon County Sheriff's Office provides police patrol and detective service for the unincorporated part of the county. The sheriff's office also provides court protection and operates the county jail. Fire and emergency medical services are provided by the Tallahassee Fire Department and Leon County Emergency Medical Services.

Tallahassee Police Department

Tallahassee is the only incorporated municipality in Leon County. The Tallahassee Police Department provides its policing. Established in 1826, TPD is the country's third-longest-accredited law enforcement agency.[26]

Education

Higher education

Florida State University

Florida State University (commonly called Florida State or FSU) is an American public space-grant and sea-grant research university. It has a 1,391.54-acre (5.631-km2) campus in Tallahassee. In 2017, it had nearly 42,000 students. It is a senior member of the State University System of Florida. Founded in 1851, it is on Florida's oldest continuous site of higher education.[27][28]

The university is classified as a Research University with Very High Research by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.[29] It comprises 16 separate colleges and more than 110 centers, facilities, labs and institutes that offer more than 360 programs of study, including professional school programs.[30] In 2022-23 the university had an operating budget of $2.36 billion[31] set by the Florida State University Board of Trustees. Florida State is home to Florida's only National Laboratory, the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory, and is the birthplace of the commercially viable anti-cancer drug Taxol. FSU also operates the John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, the State Art Museum of Florida and one of the nation's largest museum/university complexes.[32]

FSU is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS). It is home to nationally ranked programs in many academic areas, including law, business, engineering, medicine, social policy, film, music, theater, dance, visual art, political science, psychology, social work, and the sciences.[33] FSU leads Florida in four of eight areas of external funding for the STEM disciplines.[34]

For 2019, U.S. News & World Report ranked Florida State the country's 26th-best public university.[35]

Florida Governor Rick Scott and the state legislature designated FSU one of two "preeminent" state universities in the spring of 2013 among the 12 universities of the State University System of Florida.[36][37][38]

FSU's intercollegiate sports teams, commonly called the Seminoles, compete in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I and the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC). The athletics programs are favorites of passionate students, fans and alumni across the country, especially when led by the Marching Chiefs of the Florida State University College of Music. In their 113-year history, the Seminoles have won 20 national athletic championships and Seminole athletes have won 78 individual NCAA national championships.[39]

Florida A&M University

Founded on October 3, 1887, Florida A&M University (FAMU) is a public, historically black university that is part of the State University System of Florida and is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. FAMU's main campus comprises 156 buildings spread over 422 acres (1.7 km2) on top of Tallahassee's highest geographic hill. In 2016 it had more than 9,600 students. FAMU also has several satellite campuses. Its College of Law is at its Orlando site, and its pharmacy program has sites in Miami, Jacksonville and Tampa. FAMU offers 54 bachelor's degrees and 29 master's degrees. It has 12 schools and colleges and one institute.

FAMU has 11 doctoral programs, including ten Ph.D. programs: chemical engineering, civil engineering, electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, industrial engineering, biomedical engineering, physics, pharmaceutical sciences, educational leadership, and environmental sciences. Top undergraduate programs are architecture, journalism, computer information sciences, and psychology. FAMU's top graduate programs include pharmaceutical sciences, public health, physical therapy, engineering, physics, master's of applied social sciences (especially history and public administration), business, and sociology.

Tallahassee Community College

The Florida Legislature founded Tallahassee Community College in 1966.[41] TCC is a member of the Florida College System. It is accredited by the Florida Department of Education and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. Its primary site is a 270-acre (1.092 km2) campus in Tallahassee.

TCC offers Bachelor's of Science, Associate of Arts, Associate of Science, and Associate of Applied Sciences degrees. In 2013, it was 1st in the nation in graduating students with A.A. degrees.[42] TCC is also the nation's #1 transfer school to Florida State University. As of 2015, TCC had 38,017 students.[43]

In partnership with Florida State University, TCC offers the TCC2FSU program. This program provides guaranteed admission to FSU for TCC Associate in Arts degree graduates.[44]

List of other colleges

Primary and secondary education

The Leon County School District administers and operates Leon County's public schools.[45] LCS is operated by a superintendent, 5 board members, and 1 student representative. There are 25 elementary schools, 10 middle schools, seven high schools, eight special/alternative schools, and two charter schools.

List of middle schools

- Cobb Middle School

- Deerlake Middle School

- Fairview Middle School

- Fort Braden School K - 8

- Governor's Charter Academy (Charter K–8)

- Griffin Middle School

- Holy Comforter Episcopal School (Private PK3–8)

- Maclay School (Private PK3–12)

- Montford Middle School

- Nims Middle School

- Raa Middle School

- Success Academy of Tallahassee

- Swift Creek Middle School

- Stars Middle School (Charter)

- School of Arts and Sciences (Charter K–8)

- Tallahassee School of Math and Science (Charter K–8)

- Trinity Catholic School (Private PK3–8)

- Cornerstone Learning Community (Private PK3–8)

List of high schools

- Amos P. Godby High School

- Atlantis Academy

- Community Christian School

- Florida A&M University Developmental Research School

- Florida State University High School

- James S. Rickards High School

- John Paul II Catholic High School

- Lawton Chiles High School

- Leon High School

- Lincoln High School

- Lively Technical Center

- Maclay School

- North Florida Christian High School

- SAIL High School

- Woodland Hall Academy

Libraries

Leon County operates the Leroy Collins Leon County Public Library, with 7 branches serving the county:[46]

- Leroy Collins Main Library

- Northeast Branch Library

- Eastside Branch Library

- Dr. B.L. Perry, Jr. Branch Library

- Lake Jackson Branch Library

- Woodville Branch Library

- Jane G. Sauls Fort Braden Branch Library

The Leon County Public Library was renamed in 1993 to honor LeRoy Collins, the 33rd governor of Florida.[47]

History of library services

The Carnegie Library of Tallahassee provided library services to the black community before desegregation. It was the first and only public library in Tallahassee until 1955. Philanthropist Andrew Carnegie offered Tallahassee money to build a public library in 1906. According to Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, the library was built on the FAMU campus because the city refused the donation because it would have to serve the black citizens. "The facility boasted modern amenities such as electricity, indoor plumbing and water supplied by the city. In later years, the Library served as an art gallery, religious center, and in 1976, became the founding home of the Black Archives Research Center and Museum. By functioning both as a repository for archival records and a museum for historical regalia, the center continues to render academic support to educational institutions, civic, political, religious and Museum. By functioning both as a repository for archival records and a museum for historical regalia, the center continues to render academic support to educational institutions, civic, political, religious and social groups, as well as, public and private businesses throughout Florida and the nation."[48] The building was designed by noted architect William Augustus Edwards and was built in 1908. On November 17, 1978, it was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

The Carnegie Library of Tallahassee, which served only the black community, became the only free public library in the city until 1955. According to the Leon County Public Library's website, the American Association of University Women formed the Friends of the Library organization in 1954. The formation of the Friends of the Library was in direct response to the fact that "Tallahassee was the only state capital in the United States not offering free public library service."[49] A year later, the library was established by legislative action and developed by citizens and civic groups. The first Leon County free public library opened on March 21, 1956. The first building to house the library was The Columns, one of the oldest remaining antebellum homes in the Leon County area, at Park Avenue and Adams Street (now the home of the James Madison Institute).

In order to expand library services, the Junior League of Tallahassee donated a bookmobile to the library. The vehicle was later donated to the Leon County Sheriff's Office to be used as a paddywagon for its Road Prison. In 1962, the library moved to the old Elks Club building at 127 North Monroe Street. Public transit in the city of Tallahassee had been desegregated by 1958, but the public library system was only integrated several years later.

In the early 1970s, Jefferson and Wakulla Counties joined the Leon County Public Library System, forming the Leon, Jefferson, and Wakulla County Public Library System. According to the library's website, "Leon County provided administrative and other services to the two smaller counties, while each supported the direct costs of their library services and their share of Leon's administrative costs."[49] In 1975 the system started a branch library in Bond, a predominantly black community on the city's south side. Wakulla County left the library cooperative in 1975 to start its own library system and in 1978 the main library moved to Tallahassee's Northwood Mall. Jefferson County left the library cooperative in 1980 and the library reverted to the Leon County Public Library. In 1989, "ground breaking was held on March 4 for a new $8.5 million main library facility with 88,000 feet of space. The site was next door to the library's original home, The Columns, which had been moved in 1971 to 100 N. Duval."[49] The new library had its grand opening in 1991 and was renamed in 1993 in honor of former Governor LeRoy Collins.

Points of interest

- Alfred B. Maclay Gardens State Park

- Apalachicola National Forest

- Birdsong Nature Center

- Bradley's Country Store Complex

- Florida State Capitol

- Florida Supreme Court

- Florida State Archives

- Florida Vietnam War Memorial

- Lake Jackson Mounds Archaeological State Park

- Leon County Fairgrounds

- Leon County's five canopy roads

- LeRoy Collins Leon County Public Library

- Mission San Luis de Apalachee

- Museum of Florida History

- Old Fort Park

- Tall Timbers Research Station

- Tallahassee Antique Car Museum

- Tallahassee Museum

- Tallahassee-St. Marks Historic Railroad Trail State Park

Transportation

Major highways

Communities

City

Census-designated places

Other unincorporated communities

- Baum

- Belair

- Black Creek

- Bloxham

- Centerville

- Chaires Crossroads

- Felkel

- Gardner

- Iamonia

- Ivan

- Lafayette

- Lutterloh

- Meridian

- Ochlockonee

- Rose

- Wadesboro

Defunct entity

- Bond-South City, a former census-designated place enumerated by the United States Census Bureau in 1950 and 1960.

Notable people

- Wally Amos – founder of the "Famous Amos" chocolate chip cookie brand; actor

- Tony Hale – actor, played Byron "Buster" Bluth on Arrested Development

- Isaac Jenkins (1846-1911), politician who served in the Florida House of Representatives in the 1880s

- Jerrie Mock – aviator and first woman to fly around the world solo

- T-Pain (born Faheem Najm) – hip hop and R&B singer

- Ernest I. Thomas – raiser of the original flag at Iwo Jima

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 30, 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Leon County, Florida". www.census.gov. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Publications of the Florida Historical Society. Florida Historical Society. 1908. p. 32.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 185.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Geology of Florida, University of Florida". Archived from the original on December 28, 2009.

- "South Florida Information Access (SOFIA) -- USGS Greater Everglades Ecosystems Science". archive.usgs.gov. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 14, 2014.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- Bureau, US Census. "Census.gov". Census.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- "Leon County, FL - county education levels - ePodunk". www.epodunk.com. Archived from the original on June 9, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- Eisenberg, Daniel (1986). "In Tallahassee" (PDF). Journal of Hispanic Philology. Vol. 10, no. 2. pp. 97–101. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2014.

- "Home - Leon County Supervisor of Elections". www.leonvotes.org. Archived from the original on August 10, 2014. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- "Home - Leon County Supervisor of Elections". www.leonvotes.gov. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- "Republican Jason Shoaf wins House District 7 special election". Florida Politics. June 19, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- "Consolidation of City (Tallahassee) & County (Leon) Government" (PDF). Leon County Supervisor of Elections. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- "City County Consolidation Efforts: Selective Incentives and Institutional Choice" (PDF). www.fsu.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2007.

- TPD web site

- Meginniss, Benjamin A.; Winthrop, Francis B.; Ames, Henrietta O.; Belcher, Burton E.; Paret, Blanche; Holliday, Roderick M.; Crawford, William B.; Belcher, Irving J. (1902). "The Argo of the Florida State College". The Franklin Printing & Publishing Co., Atlanta. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- Klein, Barry (July 29, 2000). "FSU's age change: history or one-upmanship?". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- "Florida State University". Classifications. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Colleges, Schools, Departments, Institutes, and Administrative Units". FSU Departments. Florida State University. April 26, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- Farnum-Patronis, Amy. "FSU Board of Trustees approves $2.36 billion operating budget for 2022-2023". News.fsu.edu. Florida State University. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- "The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art". FSU Departments. The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art. April 26, 2013. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Florida State University – College Highlights and Selected National Rankings". Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- "FSU Highlights". fsu.edu.

- "Florida State University - US News Best Colleges". Profile, Rankings and Data. March 10, 2016. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- Call, James (June 10, 2013). "UF, FSU get special designation, more money". The Florida Current. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- "CS/CS/SB 1076: K-20 Education". Flsenate.gov. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- "Our Opinion: FSU benefits from pre-eminent status". The Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- Joanos, Jim (June 2012). "FSU Athletics Timeline". Retrieved April 26, 2013.

- "Lee Hall Auditorium : Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University 2017". Famu.edu. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "Admissions - Tallahassee Community College". www.tcc.fl.edu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2019.

- "Associate Degree & Certificate Producers, 2013". Ccweek.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Library - Tallahassee Community College". Tcc.fl.edu. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Leon County, FL" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 31, 2022. - Text list

- "Leroy Collins Leon County Public Library". Leon County. Retrieved January 9, 2020.

- "Governor Thomas LeRoy Collins". LeRoy Collins Leon County Public Library. Retrieved October 27, 2014.

- "Carrie Meek - James N. Eaton, Sr. Southeastern Regional Black Archives Research Center and Museum" (PDF). Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies. 10 (2): 263–272. 2017.

- Leon County. (2002-2016). Library History. Retrieved April 9, 2018, from Leon County Florida Government: http://cms.leoncountyfl.gov/Library/LibraryInformation/Library-History

- "Tallahassee's airport goes international". Tallahassee Democrat. Retrieved July 8, 2015.