Indigenous people of the Everglades region

The indigenous people of the Everglades region arrived in the Florida peninsula of what is now the United States approximately 14,000 to 15,000 years ago, probably following large game. The Paleo-Indians found an arid landscape that supported plants and animals adapted to prairie and xeric scrub conditions. Large animals became extinct in Florida around 11,000 years ago. Climate changes 6,500 years ago brought a wetter landscape. The Paleo-Indians slowly adapted to the new conditions. Archaeologists call the cultures that resulted from the adaptations Archaic peoples. They were better suited for environmental changes than their ancestors, and created many tools with the resources they had. Approximately 5,000 years ago, the climate shifted again to cause the regular flooding from Lake Okeechobee that gave rise to the Everglades ecosystems.

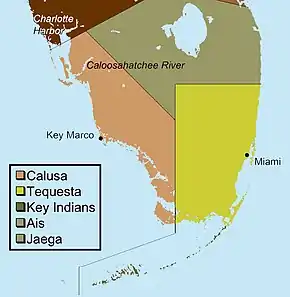

From the Archaic peoples, two major tribes emerged in the area: the Calusa and the Tequesta. The earliest written descriptions of these people come from Spanish explorers, who sought to convert and conquer them. Although they lived in complex societies, little evidence of their existence remains today. The Calusa were more powerful in number and political structure. Their territory was centered on modern-day Ft. Myers, and extended as far north as Tampa, as far east as Lake Okeechobee, and as far south as the Keys. The Tequesta lived on the southeastern coast of the Florida peninsula around what is today Biscayne Bay and the Miami River. Both societies were well adapted to live in the various ecosystems of the Everglades regions. Their people often traveled through the heart of the Everglades, though they rarely lived within it.

After more than 210 years of relations with the Spanish, both indigenous societies lost cohesiveness. Official records indicate that survivors of war and disease were transported to Havana with Spanish colonists in the late 18th century, after Great Britain took over some of the territory. Isolated groups may have been assimilated into the Seminole nation, which formed in northern Florida when a band of Creek consolidated surviving members of pre-Columbian societies in Florida into their own group to become a distinct tribe, in a process of ethnogenesis. They also were joined by free blacks and escaped slaves, who became known as Black Seminole. The Seminole were forced south and into the Everglades by the U.S. military during the Seminole Wars from 1835 to 1842. The U.S. military pursued the Seminole into the region, which resulted in some of the first recorded European-American explorations of much of the area. Federally recognized Seminole tribes continue to live in the Everglades region. Since the late 20th century, they have developed casino gambling on six reservations in the state, which generate revenues for the welfare and education of their tribes.

Prehistoric peoples

| Period | Dates |

|---|---|

| Paleo-Indian | 10,000–7,000 BCE |

| Archaic: Early Middle Late |

7,000–5,000 BCE 5,000–3,000 BCE 3,000–1,500 BCE |

| Transitional | 1,500–500 BCE |

| Glades I | 500 BCE–800 CE |

| Glades II | 800–1200 |

| Glades III | 1200–1566 |

| Historic | 1566–1763 |

Humans first inhabited the peninsula of Florida approximately 14,000 to 15,000 years ago; it looked vastly different at that time and had a different climate.[2][3] The west coast extended about 100 miles (160 km) to the west of its current location.[4] The landscape had large dunes and sweeping winds characteristic of an arid region, and pollen samples show foliage was limited to small stands of oak and scrub bushes. As Earth's glacial ice retreated, winds slowed and vegetation became more prevalent and varied.[5] The Paleo-Indian diets consisted of small plants and available wild game, which included saber-toothed cats, ground sloths, and spectacled bears.[6] The Pleistocene megafauna died out around 11,000 years ago.[7] Around 6,500 years ago, the climate of Florida changed again during the Holocene climatic optimum and became much wetter. Paleo-Indians spent more time in camps and less time traveling between sources of water.[8]

The Paleo-Indians who survived are now known as the Archaic peoples of the Florida peninsula. They lived on after the extinction of most big game and were primarily hunter-gatherers who depended on smaller game and fish. They relied on plants for food more than their ancestors. They were able to adapt to the shifting climate and the resulting changes in animal and plant populations.

Florida experienced a prolonged drought at the onset of the Early Archaic era that lasted until the Middle Archaic period. Although the population decreased overall on the peninsula, their use of tools increased significantly during this time. Artifacts demonstrate that these people used drills, knives, choppers, atlatls, and awls made from stone, antlers, and bone.[9]

During the Late Archaic period, the climate became wetter again and by approximately 3000 BCE, the rise of water tables allowed an increase in population. Cultural development also took place. Florida Indians formed into three similar but distinct cultures: Okeechobee, Caloosahatchee, and Glades, named for the bodies of water where they were centered.[10]

The Glades culture is divided into three periods based on evidence found in middens. In 1947, archaeologist John Goggin described the three periods after examining shell mounds. He excavated one on Matecumbe Key, another at Gordon Pass near modern-day Naples, and a third south of Lake Okeechobee near modern-day Belle Glade. The Glades I culture, lasting from 500 BCE to 800 CE, was apparently focused around Gordon Pass and is considered the least sophisticated due to the lack of artifacts. What has been found—primarily pottery—is gritty and plain.[11] With the advent of a well-established culture in 800 CE, the Glades II period is characterized by more ornate pottery, wide use of tools throughout the South Florida region, and the appearance of religious artifacts at burial sites. By 1200, the Glades III culture exhibited the height of their development. Pottery became ornate enough to be subdivided into types of decoration. More importantly, evidence of an expanding culture is revealed through the development of ceremonial ornaments made from shell, and the construction of large earthworks associated with burial rituals.[11] From the Glades III culture developed two distinct tribes that lived in and near the Everglades in the historic period: the Calusa and the Tequesta.

Calusa

What is known of the inhabitants of Florida after 1566 was recorded by European explorers and settlers. Juan Ponce de León is credited as the first European to have contact with Florida's indigenous people in 1513. Ponce de León met with hostility from tribes that may have been the Ais and the Tequesta before rounding Cape Sable to meet the Calusa, the largest and most powerful tribe in South Florida. Ponce de León found at least one of the Calusa fluent in Spanish.[13] The explorer assumed the Spanish-speaker was from Hispaniola, but anthropologists have suggested that communication and trade between Calusa and native people in Cuba and the Florida Keys was common, or that Ponce de León was not the first Spaniard to make contact with the native people of Florida.[14] During his second visit to South Florida, Ponce de León was killed by the Calusa, and the tribe gained a reputation for violence, causing future explorers to avoid them.[15] In the more than 200 years the Calusa had relations with the Spanish, they were able to resist their attempts to missionize them.

The Calusa were referred to as Carlos by the Spanish, which may have sounded like Calos, a variation of the Muskogean word kalo meaning "black" or "powerful".[16] Much of what is known about the Calusa was provided by Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda. Fontaneda was a 13-year-old boy who was the only survivor of a shipwreck off the coast of Florida in 1545. For seventeen years he lived with the Calusa until explorer Pedro Menéndez de Avilés found him in 1566. Menéndez took Fontaneda to Spain where he wrote about his experiences. Menéndez approached the Calusa with the intention of establishing relations with them to ease the settlement of the future Spanish colony. The chief, or cacique, was called Carlos by the Spanish. Positions of importance in Calusa society were given the adopted names Carlos and Felipe, transliterated from Spanish royal tradition.[17] However, the cacique Carlos described by Fontaneda was the most powerful chief during Spanish colonization. Menéndez married his sister in order to facilitate relations between the Spanish and the Calusa.[18] This arrangement was common in societies in South Florida people. Polygamy was a method of solving disputes or settling agreements between rival towns.[19] Menéndez, however, was already married and expressed discomfort with the union. Unable to avoid the marriage, he took Carlos' sister to Havana where she was educated, and where one account reported that she died years later, the marriage never consummated.[20]

Fontaneda explained in his 1571 memoir that Carlos controlled fifty villages located on Florida's west coast, around Lake Okeechobee (which they called Mayaimi) and on the Florida Keys (which they called Martires). Smaller tribes of Ais and Jaega who lived to the east of Lake Okeechobee, paid regular tributes to Carlos. The Spanish suspected the Calusa of harvesting treasures from shipwrecks and distributing the gold and silver between the Ais and Jaega, with Carlos receiving the majority.[21] The main village of the Calusa, and home of Carlos, bordered Estero Bay at present-day Mound Key where the Caloosahatchee River meets the Gulf of Mexico.[22] Fontaneda described human sacrifice as a common practice: when the child of a cacique died, each resident gave up a child to be sacrificed, and when the cacique died, his servants were sacrificed to join him. Each year a Christian was required to be sacrificed to appease a Calusa idol.[23] The building of shell mounds of varying sizes and shapes was also of spiritual significance to the Calusa. In 1895 Frank Hamilton Cushing excavated a massive shell mound on Key Marco that was composed of several constructed terraces hundreds of yards long. Cushing unearthed over a thousand Calusa artifacts. Among them he found tools made of bone and shell, pottery, human bones, masks, and animal carvings made of wood.[24]

The Calusa, like their predecessors, were hunter-gatherers who existed on small game, fish, turtles, alligators, shellfish, and various plants.[25] Finding little use for the soft limestone of the area, they made most of their tools from bone or teeth, although they also found sharpened reeds effective. Weapons consisted of bows and arrows, atlatls, and spears. Most villages were located at the mouths of rivers or on key islands. They used canoes for transportation, as evidenced by shell mounds in and around the Everglades that border canoe trails. South Florida tribes often canoed through the Everglades, but rarely lived in them.[26] Canoe trips to Cuba were also common.[27]

Calusa villages often had more than 200 inhabitants, and their society was organized in a hierarchy. Apart from the cacique, other strata included priests and warriors. Family bonds promoted the hierarchy, and marriage between siblings was common among the elite. Fontaneda wrote, "These Indians have no gold, no silver, and less clothing. They go naked except for some breech cloths woven of palms, with which the men cover themselves; the women do the like with certain grass that grows on trees. This grass looks like wool, although it is different from it".[28] Only one instance of structures was described: Carlos met Menéndez in a large house with windows and room for over a thousand people.[29]

The Spanish found Carlos uncontrollable, as their priests and the Calusa fought almost constantly. Carlos was killed when a Spanish soldier shot him with a crossbow.[30] Following Carlos' death, leadership of the society passed to the war chief Felipe, who was also killed by the Spanish shortly after.[17] Estimated numbers of Calusa at the beginning of the occupation of the Spanish ranged from 4,000 to 7,000.[31] The society endured a decline of power and population after Carlos; by 1697 their number was estimated to be about 1,000.[27] In the early 18th century, the Calusa came under attack from the Yamasee to the north; many asked to be removed to Cuba, where almost 200 died of illness. Some of these later relocated to Florida,[32] and remnants may have been eventually assimilated into the Seminole culture, which developed during the 18th century.[33]

Tequesta

Second in power and number to the Calusa in South Florida were the Tequesta (also called Tekesta, Tequeste, and Tegesta). They occupied the southeastern portion of the lower peninsula in modern-day Dade, Broward, and the southern half of Palm Beach counties. They may have been controlled by the Calusa, but accounts state that they sometimes refused to comply with the Calusa caciques, which resulted in war.[22] Like the Calusa, they rarely lived within the Everglades, but found the coastal prairies and pine rocklands to the east of the freshwater sloughs habitable. To the north, their territory was bordered by the Ais and Jaega. Like the Calusa, the Tequesta societies centered on the mouths of rivers. Their main village was probably on the Miami River or Little River. A large shell mound on the Little River marks where a village once stood.[34] Though little remains of the Tequesta society, a site of archeological importance called the Miami Circle was discovered in 1998 in downtown Miami. It may be the remains of a Tequesta structure.[35] Its significance has yet to be determined, though archeologists and anthropologists continue to study it.[36]

The Spanish described the Tequesta as greatly feared by their sailors, who suspected the natives of torturing and killing survivors of shipwrecks. Spanish priests wrote that the Tequesta performed child sacrifices to mark the occasion of making peace with a tribe with whom they had been fighting. Like the Calusa, the Tequesta hunted small game, but depended more upon roots and less on shellfish in their diets. They did not practice cultivated agriculture. They were skilled canoeists and hunted in the open ocean for what Fontaneda described as whales, but were probably manatees. They lassoed the manatees and drove a stake through their snouts.[23][34]

The first contact with Spanish explorers occurred in 1513 when Juan Ponce de León stopped at a bay he called Chequescha, or Biscayne Bay. Finding the Tequesta unwelcoming, he left to make contact with the Calusa. Menéndez met the Tequesta in 1565 and maintained a friendly relationship with them, building some houses and setting up a mission. He also took the chief's nephew to Havana to be educated, and the chief's brother to Spain. After Menéndez visited, there are few records of the Tequesta: a reference to them in 1673, and further Spanish contact to convert them.[37] The last reference to the Tequesta during their existence was written in 1743 by a Spanish priest named Father Alaña, who described their ongoing assault by another tribe. The survivors numbered only 30, and the Spanish transported them to Havana. In 1770 a British surveyor described multiple deserted villages in the region where the Tequesta had lived.[38] Archeologist John Goggin suggested that by the time European Americans settled the area in 1820, any remaining Tequesta were assimilated into the Seminole people.[34] Common descriptions of Native Americans in Florida by 1820 identified only the "Seminoles".[39]

Seminole / Miccosukee

Following the demise of the Calusa and Tequesta, Native Americans in southern Florida were referred to as "Spanish Indians" in the 1740s, probably due to their friendlier relations with Spain. Between the Spanish defeat in the Seven Years' War in 1763 and the end of the American War of Independence in 1783, the United Kingdom ruled Florida. The first known use of the term "Seminolie" is from a British Indian agent in a document dated 1771.[40] The beginnings of the tribe are vague, but records show that Creeks invaded the Florida peninsula, conquering and assimilating what was left of pre-Columbian societies into the Creek Confederacy. The mixing of cultures is evident in the language influences present among the Seminoles: various Muskogean languages, notably Hitchiti, and Creek, as well as Timucuan. In the early 19th century, a US Indian agent explained the Seminoles this way: "The word Seminole means runaway or broken off. Hence ... applicable to all the Indians in the Territory of Florida as all of them ran away ... from the Creek ... Nation".[41] Linguistically, the term "Seminole" comes from a corruption of the Spanish word "cimarron," likening their migratory history to wild horses. The traditional Muskogee Creek Language lacks a rhotic phoneme. There was a metathesis of the penultimate and ultimate syllables.

.jpg.webp)

Creeks, who were centered in modern-day Alabama and Georgia, were known to incorporate conquered tribes into their own. Some Africans escaping slavery from South Carolina and Georgia fled to Florida, lured by Spanish promises of freedom should they convert to Catholicism, and found their way into the tribe.[42] Seminoles originally settled in the northern portion of the territory, but the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek forced them to live on a 5-million-acre (20,000 km2) reservation north of Lake Okeechobee. They soon ranged farther south, where they numbered approximately 300 in the Everglades region,[43] including bands of Miccosukees—a similar tribe who spoke a different language—who lived in The Big Cypress.[44] Unlike the Calusa and Tequesta, the Seminole depended more on agriculture and raised domesticated animals. They hunted for what they ate, and traded with European-American settlers. They lived in structures called chickees, open-sided palm-thatched huts, probably adapted from the Calusa.[45]

In 1817, Andrew Jackson invaded Florida to hasten its annexation to the United States in what became the First Seminole War. After Florida became a U.S. territory and settlement increased, conflicts between colonists and Seminoles became more frequent. The Second Seminole War (1835–1842) resulted in almost 4,000 Seminoles in Florida being displaced or killed. The Seminole Wars pushed the Indians farther south and into the Everglades. Those who did not find refuge in the Everglades were relocated to Oklahoma Indian territory under Indian Removal.

The Third Seminole War lasted from 1855 to 1859. Over its course, 20 Seminoles were killed and 240 were removed.[44] By 1913, Seminoles in the Everglades numbered no more than 325.[46] They made their villages in hardwood hammocks, islands of hardwood trees that formed in rivers or pine rockland forests. Seminole diets consisted of hominy and coontie roots, fish, turtles, venison, and small game.[46] Villages were not large, due to the limited size of hammocks, which on average measured between one and 10 acres (40,000 m2). In the center of the village was a cook-house, and the largest structure was reserved for eating. When the Seminoles lived in northern Florida, they wore animal-skin clothing similar to their Creek predecessors. The heat and humidity of the Everglades influenced their adapting a different style of dress. Seminoles replaced their heavier buckskins with clothing of unique calico patchwork designs made of lighter cotton, or silk for more formal occasions.[47]

The Seminole Wars increased the U.S. military presence in the Everglades, which resulted in the exploration and mapping of many regions that had not previously been recorded.[48] The military officers who had done the mapping and charting of the Everglades were approached by Thomas Buckingham Smith in 1848 to consult on the feasibility of draining the region for agricultural use.[49]

Modern times

Between the end of the Third Seminole War and 1930, a few hundred Seminoles continued to live in relative isolation in the Everglades area. Flood control and drainage projects in the area beginning in the early 20th century opened up much land for development and significantly altered the natural environment, inundating some areas while leaving former swamps dry and arable. These projects, along with the completion of the Tamiami Trail which bisected the Everglades in 1930, simultaneously ended old ways of life and introduced new opportunities. A steady stream of white developers and tourists came to the area, and the native people began to work in local farms, ranches, and souvenir stands. They cleared land for the town of Everglades, and were "the best fire fighters [the National Park Service] could recruit" when Everglades National Park caught fire in times of drought.[50]

As metropolitan areas in South Florida began to grow, the Miccosukee branch of the Seminoles became closely associated with the Everglades, simultaneously seeking privacy and serving as a tourist attraction, wrestling alligators, selling crafts, and giving eco-tours of their land. As of 2008, there were six Seminole and Miccosukee reservations throughout Florida; they feature casino gaming that supports the tribe.[51]

See also

Notes and references

- McCally, p.32.

- Tommy Rodriguez (December 6, 2011). Visions of the Everglades: History Ecology Preservation. AuthorHouse. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4685-0748-5.

- Jack E. Davis (February 15, 2009). An Everglades Providence: Marjory Stoneman Douglas and the American Environmental Century. University of Georgia Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-8203-3071-6.

- Gannon, p. 2.

- McCally, p.34.

- Morgan, Gary S. (2002). "Late Rancholabrean Mammals from Southernmost Florida, and the Neotropical Influence in Florida Pleistocene Faunas". In Emry, Robert J. (ed.). Cenozoic Mammals of Land and Sea: Tributes to the Career of Clayton E. Ray. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology. Vol. 93. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 15–38.

- Fiedal, Stuart (2009). "Sudden Deaths: The Chronology of Terminal Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinction". In Haynes, Gary (ed.). American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene. Springer. pp. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8793-6_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-8792-9.

- McCally, p.35.

- McCally, p.36.

- McCally, p.37–39.

- Goggin, John (October 1947). "A Preliminary Definition of Archaeological Areas and Periods in Florida", American Antiquity, 13 (2), p.114–127.

- Griffin, p.163.

- Griffin, p.161.

- Hann, p.4–5.

- Griffin, p.161–162.

- Douglas, p.68.

- Hann, John (October 1992). "Political Leadership Among the Natives of Spanish Florida", The Florida Historical Quarterly, 71 (2), p.188–208.

- Griffin, p.162.

- Griffin, p.316.

- Hann, p.289–290.

- McCally, p.40.

- Griffin, p.164.

- Worth, John (January 1995). "Fontaneda Revisited: Five Descriptions of Sixteenth-Century Florida", The Florida Historical Quarterly, 73 (3), p.339–352.

- Cushing, Frank (December 1896). "Exploration of Ancient Key Dwellers' Remains on the Gulf Coast of Florida", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 35 (153), p.329–448.

- Tebeau, p.38–41.

- McCally, p.39.

- Griffin, p.171.

- Tebeau, p.42.

- Griffin, p.165.

- Douglas, p.171.

- Griffin, p.170.

- Griffin, p.173.

- Milanich, p. 177

- Goggin, John (April 1940). "The Tekesta Indians of Southern Florida", The Florida Historical Quarterly, 18 (4), p.274–285.

- United States Congress Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources (2003). "Miami Circle/Biscayne National Park: report (to accompany S. 111)", United States Congress Senate Report 108-4.

- Merzer, Martin (January 29, 2008). "Access to ancient site may come in near future", The Miami Herald (Florida), State and Regional News.

- Griffin, p.174.

- Tebeau, p.43.

- Tebeau, p.45.

- Griffin, p.176.

- McReynolds, p.12.

- Bateman, Rebecca (Winter, 1990). "Africans and Indians: A Comparative Study of the Black Carib and Black Seminole", Ethnohistory, 37 (1), p.1–24.

- Tebeau, p.50.

- Griffin, p.180.

- Tebeau, p.50–51

- Skinner, Alanson (January–March 1913). "Notes on the Florida Seminole", American Anthropologist, 15 (1), p.63–77.

- Blackard, David (2004). "Seminole Clothing: Colorful Patchwork". Seminole Tribe of Florida. Archived from the original on 2008-03-16. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- Tebeau, p.63–64.

- Tebeau, p.70–71.

- Tebeau, p.55–56.

- "Tourism/Enterprises". Seminole Tribe of Florida. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-02-03. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

Bibliography

- Douglas, Marjory [1947] (2002). The Everglades: River of Grass. R. Bemis Publishing. ISBN 0-912451-44-0

- Gannon, Michael, ed. (1996). The New History of Florida. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1415-8

- Griffin, John (2002). Archeology of the Everglades. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2558-3

- Hann, John (ed.) (1991). Missions to the Calusa. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1966-4

- McCally, David (1999). The Everglades: An Environmental History. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2302-5

- Milanich, Jerald (1998). Florida's Indians from Ancient Times to the Present. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1599-6

- Rodriguez, Tommy (2011). Visions of the Everglades: History Ecology Preservation. Author House. ISBN 978-1468507485

- Tebeau, Charlton (1968). Man in the Everglades: 2000 Years of Human History in the Everglades National Park. University of Miami Press.