Florida in the American Civil War

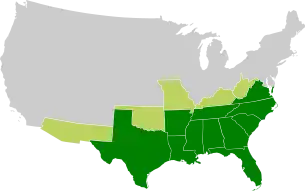

Florida participated in the American Civil War as a member of the Confederate States of America. It had been admitted to the United States as a slave state in 1845. In January 1861, Florida became the third Southern state to secede from the Union after the November 1860 presidential election victory of Abraham Lincoln. It was one of the initial seven slave states which formed the Confederacy on February 8, 1861, in advance of the American Civil War.

| Florida | |

|---|---|

.png.webp) Map of the Confederate States | |

| Capital | Tallahassee |

| Largest city | Pensacola |

| Admitted to the Confederacy | April 22, 1861 (7th) |

| Population |

|

| Forces supplied | |

| Major garrisons/armories | Fort Pickens |

| Governor | Madison Perry (1861) John Milton (1861–1865) Abraham Allison (1865) |

| Senators | Augustus Maxwell James Baker |

| Representatives | List |

| Restored to the Union | June 25, 1868 |

| History of Florida |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Confederate States in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

|

| Dual governments |

| Territory |

|

Allied tribes in Indian Territory |

Florida had by far the smallest population of the Confederate states with about 140,000 residents, nearly half of them enslaved people. As such, Florida sent around 15,000 troops to the Confederate army, the vast majority of which were deployed elsewhere during the war. The state's chief importance was as a source of cattle and other food supplies for the Confederacy, and as an entry and exit location for blockade-runners who used its many bays and small inlets to evade the Union Navy.

At the outbreak of war, the Confederate government seized many United States facilities in the state, though the Union retained control of Key West, Fort Jefferson, and Fort Pickens for the duration of the conflict. The Confederate strategy was to defend the vital farms in the interior of Florida at the expense of coastal areas. As the war progressed and southern resources dwindled, forts and towns along the coast were increasingly left undefended, allowing Union forces to occupy them with little or no resistance. Fighting in Florida was largely limited to small skirmishes with the exception of the Battle of Olustee, fought near Lake City in February 1864, when a Confederate army of over 5,000 repelled a Union attempt to disrupt Florida's food-producing region. Wartime conditions made it easier for enslaved people to escape, and many became useful informants to Union commanders. Deserters from both sides took refuge in the Florida wilderness, often attacking Confederate units and looting farms.

The war ended in April 1865. By the following month, United States control of Florida had been re-established, slavery had been abolished, and Florida's Confederate governor John Milton had committed suicide by gunshot. Florida was formally readmitted to the United States in 1868.

Background

Florida had been a Spanish territory for 300 years before being transferred to the United States in 1821. The population at the time was quite small, with most residents concentrated in the towns of St. Augustine on the Atlantic coast and Pensacola on the western end of the panhandle. The interior of the Florida Territory was home to the Seminoles and Black Seminoles along with scattered pioneers. Steamboat navigation was well established on the Apalachicola River and St. Johns River and railroads were planned, but transportation through the interior remained very difficult and growth was slow. A series of wars to forcibly remove the Seminoles from their lands raged off and on from the 1830s until the 1850s, further slowing development.

By 1840, the English-speaking population of Florida outnumbered those of Spanish colonial descent. The overall population had reached 54,477 people, with African slaves making up almost one-half.[n 1]

Florida was admitted to the union as the 27th state on March 3, 1845, when it had a population of 66,500, including about 30,000 people held in slavery.[4] By 1861, Florida's population had increased to about 140,000, of which about 63,000 were enslaved persons.[5] Their forced labor accounted for 85 percent of the state's cotton production, with most large slave-holding plantations concentrated in middle Florida, a swath of fertile farmland stretching across the northern panhandle approximately centered on the state capital at Tallahassee.

1860 U.S. presidential election

Southern Democrats walked out of the 1860 Democratic National Convention, and later nominated U.S. Vice President John C. Breckinridge to run for their party. While Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 U.S. presidential election, Breckinridge won in Florida.[6] Within days of the election, a large gathering of Marion County pioneers was held in Ocala to demand secession. Its motions were brought to the attention of the Florida House of Representatives by Rep. Daniel A. Vogt.[7]

Secession and confederation

Although the Compromise of 1850 was unpopular in Florida, the secession movement in 1851 and 1852 did not gain much traction.[8] A series of events in subsequent years exacerbated divisions.[8] By January 1860, talk of conflict had progressed to the point that Senators Stephen Mallory and David Levy Yulee jointly requested from the War Department a statement of munitions and equipment in Florida forts.

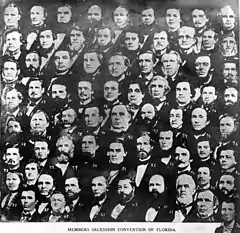

Following the election of Lincoln, a special secession convention formally known as the "Convention of the People of Florida" was called by Governor Madison S. Perry to discuss secession from the Union.[9][8][10] Delegates were selected in a statewide election, and met in Tallahassee on January 3, 1861.[11][9] Virginia planter and firebrand Edmund Ruffin came to the convention to advocate for secession.[12] Fifty-one of the 69 convention members held slaves in 1860.[8] Just seven of the delegates were born in Florida.[13]

Florida gave its reasons for leaving the Union in its Declaration of Causes for Seceding. "Each complaint related to slavery: the North's disregard for the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act; John Brown’s 1859 failed slave uprising; and William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator and Frederick Douglass’ The North Star tried to 'excite insurrection and servile war.'" The final reason was Lincoln's election.[14]

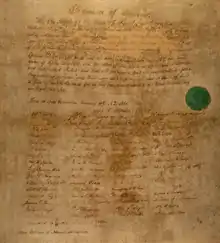

On January 5, McQueen McIntosh introduced a series of resolutions defining the purpose of the convention and the constitutionality of secession.[15] John C. McGehee, who was involved in drafting Florida's original constitution and became a judge, was elected the convention president.[16][17] Leonidas W. Spratt of South Carolina gave an impassioned speech[18] for secession.[19] Edward Bullock of Alabama also spoke to conventioneers.[8] William S. Harris was the convention's secretary. On January 7, the vote was overwhelmingly in favor of immediate secession, delegates voting sixty-two to seven to withdraw Florida from the Union.[20]

The group with the most sway that opposed secession in Florida was the Constitutional Union Party, which had several supporting newspapers including Tallahassee's Florida Sentinel. The party held its convention in June 1860 and had nominated the editor of the Sentinel, Benjamin F. Allen, for Congress. Despite being against secession, the party was composed mostly of slave-owning planters and conservative democrats.[21]

Individuals who opposed secession included Conservative plantation owner and former Seminole War military commander Richard Keith Call, who advocated for restraint and judiciousness.[22] His daughter Ellen Call Long wrote that upon being told of the vote outcome by its supporters, Call raised his cane above his head and told the delegates who came to his house, "And what have you done? You have opened the gates of hell, from which shall flow the curses of the damned, which shall sink you to perdition."[22] In response, Call, and others against secession, were called names like "submissionists" and "Union Shriekers." Pro-unionists in Florida not only faced public ridicule, some could be attacked and even killed. One example was the case of William Hollingsworth who was shot at and seriously wounded by a group of secessionists who called themselves regulators.[21]

A formal Ordinance of Secession was introduced for debate on January 8. The primary topic of debate was whether Florida should immediately secede or wait until other southern states such as Alabama officially chose to secede.[23] Outspoken supporters of secession at the conference included Governor Perry and Governor-elect John Milton. Jackson Morton and George Taliaferro Ward attempted to have the ordinance amended so that Florida would not secede before Georgia and Alabama, but their proposal was voted down. When Ward signed the Ordinance he stated "When I die, I want it inscribed upon my tombstone that I was the last man to give up the ship."[24]

On January 10, 1861, the delegates formally adopted the Ordinance of Secession, which declared that the "nation of Florida" had withdrawn from the "American union."[9] Florida was the third state to secede, following South Carolina and Mississippi. By the following month, six states had seceded;[25] These six had the largest population of enslaved people among the Southern states.

Secession was declared and a public ceremony held on the east steps of the Florida capitol the following day; an Ordinance of Secession was signed by 69 people.[9] The public in Tallahassee celebrated the announcement of secession with fireworks and a large parade.[26] The secession ordinance of Florida simply declared its severing of ties with the federal Union, without stating any causes.[9] According to historian William C. Davis, "protection of slavery" was "the explicit reason" for Florida's secession, as well as for the creation of the Confederacy itself.[27] Supporters of secession included the St. Augustine Examiner.[28] The governors of Georgia and Mississippi sent telegrams affirming support for immediate secession.[12]

During the secession convention, president John McGehee stated: "At the South and with our people, of course, slavery is the element of all value, and a destruction of that destroys all that is property. This party, now soon to take possession of the powers of government, is sectional, irresponsible to us, and, driven on by an infuriated, fanatical madness that defies all opposition, must inevitably destroy every vestige of right growing out of property in slaves.”[29]

The delegates adopted a new state constitution and within a month the state joined other southern states to form the Confederate States of America.[20] Florida's Senator Mallory was selected to be Secretary of the Navy in the first Confederate cabinet under president Jefferson Davis. The convention had further meetings in 1861 and into 1862. There was a Unionist minority in the state, an element that grew as the war progressed.

In a message to the state legislature on November 27,1860, Governor Perry requested $100,000 in funding for the state military as well as a new militia law. The legislature approved the funding but did not enact any new militia laws. Perry took the funds to buy arms in South Carolina.[30]

Florida sent a three-man delegation to the 1861-62 Provisional Confederate Congress, which first met in Montgomery, Alabama, and then in the new capital of Richmond, Virginia. The delegation consisted of Jackson Morton, James Byeram Owens, and James Patton Anderson, who resigned April 8, 1861, and was replaced by G. T. Ward. Ward served from May 1861 until February 1862, when he resigned and was replaced by John Pease Sanderson.

In June 1861, the Confederate government split Florida up into military districts led by Confederate commanders who were given the power to requisition soldiers from the governor, more specifically from the state's militia. By March 1862, the state convention had abolished the state militia in an effort to create a more unified Confederate military organization.[31]

Civil War

Economy

Governor John Milton stressed throughout the war the importance of Florida as a supplier of goods, rather than personnel. Florida was a substantial provider of food (particularly beef cattle) for the Confederate Army. However, many Florida planters continued to grow cotton and other cash crops despite pleas from Confederate officials and Governor Milton to grow food crops instead.[32] Another vital resource that Florida provided was salt. The state's long coastline made it ideal for salt production. Numerous saltworks were established on both coasts but most were located on the Gulf from Tampa Bay up through the Panhandle. Recognizing the importance of Florida salt, in 1862 the U.S. Navy began raiding operations against saltworks in the state.[33]

Florida's food supply became even more crucial for the Confederacy following the Fall of Vicksburg. This pivotal event effectively divided the Confederacy at the Mississippi River, making it impractical for the eastern armies to receive essential supplies from the western regions. As a result, Florida's role as a provider of food became even more significant in sustaining the Confederate forces in the eastern theater of the war.[34]

Blockade

As Florida was an important supply route for the Confederate army, Union forces operated a blockade around the entire state. The 8,436-mile coastline and 11,000 miles of rivers, streams, and waterways proved a haven for blockade runners and a daunting task for patrols by Federal warships.

The Confederates attempted to use the close proximity of Florida with Cuba to continue trade with Spain and the rest of Europe in spite of the blockade. The rebel government wished to develop relationships with the Spanish government in the hopes that they would help the Confederate war effort or, at the least, not hamper it. On the other hand, Spain resisted selling arms and ammunition to the Confederacy in order to remain as neutral as possible. The trade that did continue, the majority of which went through Cuba and Florida, included the exportation of cotton and importation of food, cigars, medical supplies and Spanish army surplus shoes.[35]

Union troops occupied major ports such as Apalachicola, Cedar Key, Jacksonville, Key West, and Pensacola early in the war. USS Hatteras had blockade duty in Apalachicola, and, in January 1862, was part of a Union naval force which landed in Cedar Key and burned several ships, a pier, and flatcars.[36]

After the U.S. Navy captured St. Augustine in mid-March of 1862, its harbor was closed to all except Northern ships. Gun boats were also sent on patrols up the St. Johns River all the way to Lake George. This riverine blockade force not only prevented Confederate troop and supply movements, it also became a pick-up point for rebel deserters and pro-Union Floridians.[37]

Slavery

The majority of enslaved people, much like the majority of the white population, resided in North Florida during the war, while Southern Florida, aside from Key West, remained a largely "undeveloped frontier."[38] Confederate authorities used enslaved people as teamsters to transport supplies and as laborers in salt works and fisheries. Many enslaved people working in these coastal industries escaped to the relative safety of Union-controlled enclaves during the war. In particular, many enslaved people fled to Key West because of the relatively large free black population (the 1860 census for Key West lists 2302 white people, 435 enslaved people, and 156 free black people) and the presence of a Union garrison. The Union army utilized slave labor south of the Mason Dixon line. During 1861 and 1862, the Department of War's payroll showed that Fort Zachary Taylor averaged forty-five slave laborers per month.[38] The Confederacy also utilized slave labor and Florida was the first state to pass legislation that authorized the government to impress slaves. Slave owners were compensated $25 a month per slave impressed.[39] Beginning in 1862, Union military activity in East and West Florida encouraged enslaved people in plantation areas to flee their owners in search of freedom. Planter fears of uprisings by enslaved people increased as the war went on.[40]

Some worked on Union ships and, beginning in 1863, more than a thousand enlisted as soldiers in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) or as sailors in the Union Navy.[40] Companies D and I of the 2nd USCT were moved from their station at Key West to Fort Myers on April 20, 1864. These men would go on to help disrupt the Confederate cattle supply and help free enslaved people in the area.[38] In mid-May 1864, a delegation of Miccosukee entered Fort Myers and told Union officers there that they had been lied to and treated poorly by the Confederates. The appearance of black soldiers as part of the garrison there helped further convince the Native Americans to work with Federal troops rather than their Confederate counterparts.[41]

In January 1865, Union General William T. Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15 that set aside a portion of Florida as designated territory for runaway and freed former enslaved people who had accompanied his command during its March to the Sea. These controversial orders were not enforced in Florida, and were later revoked by President Andrew Johnson.

Currency

On February 14, 1861, the state legislature authorized Chapter 1097 of the Laws of Florida, which allowed for the issuing of banknotes. However, due to legal and logistical challenges, the notes did not actually start circulating until September and October 1861. At least two specimens, or proofs, were created by Peter Hawes of New Orleans but it was Hoyer & Ludwig of Richmond, an already established security printer for the Confederacy, who ended up with the contract to produce the notes. However, there is also some documentary evidence that a Florida firm, Dyke and Carlisle, was indirectly involved in producing the notes. From 1861 to 1862, the originally authorized $500,000 was issued. In 1863, an additional $340,000 in 1861-dated notes were issued, supposedly to aid soldiers families.

The notes were issued in, at least, the following denominations: $1, $2, $3, $5, $10, $20 $50, $100.[42]

Deserters

Growing public dissatisfaction with Confederate conscription and impressment policies encouraged desertion by Confederate soldiers. Several Florida counties became havens for Florida deserters, as well as deserters from other Confederate states. Deserter bands attacked Confederate patrols, launched raids on plantations, confiscated slaves, stole cattle, and provided intelligence to Union army units and naval blockaders. Although most deserters formed their own raiding bands or simply tried to remain free from Confederate authorities, other deserters and Unionist Floridians, joined regular Federal units for military service in Florida.[40]

For example, Taylor County was home to William Strickland and his band of deserters and Unionists called "The Royal Rangers." In 1864, a Confederate colonel tasked with hunting down deserters, broke into Strickland's home and found a membership list of 35 men who "bear true allegiance to the United States of America." Despite their names being identified and homes burned to the ground, few members of the Royal Rangers surrendered.[43][44]

Another effective band of deserters operated out of Fort Myers. They harassed the Confederate supply chain, especially cattle. Reinforced with union Supplies and troops, including members of the 2nd United States Colored Infantry Regiment, the garrison at Fort Myers proved enough of a thorn in the Confederacy's side that a force was deployed to take the fort, resulting in a small engagement dubbed the Battle of Fort Myers. The Confederates retreated after failing to take the fort.[45]

Military Situation

Of the state's total population of 140,000, only about 16,000 were white males between the ages of 18-45, or otherwise eligible for military service.[46] Despite this, the state raised some 15,000 troops for the Confederacy, which were organized into twelve regiments of infantry and two of cavalry, as well as several artillery batteries and supporting units. The state's small population, relatively remote location, and meager industry limited its overall strategic importance. Battles in Florida were mostly small skirmishes, as neither army aggressively sought control of the state.[47]

Seminoles

In 1862, the Florida House of Representatives established a Committee on Indian Affairs in an effort to improve relations with the Seminole and prevent them from fighting on the side of the Union. However, little else was done to help the Seminole and the growing number of Federal troops in the state led the tribe to remain officially neutral throughout the conflict. Despite this, some Seminole did sign on to fight for the Confederacy,[48] while others, like Halleck Tustenuggee and Sonuk Mikko (Billy Bowlegs), fought for the Union.[49]

Forts and Other Military Installations

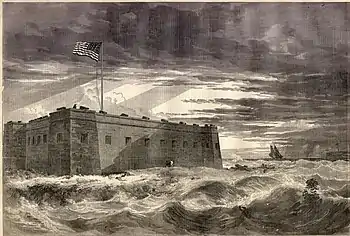

Governor Milton also worked to strengthen the state militia and to improve fortifications and key defensive positions. Confederate forces moved quickly to seize control of many of Florida's U.S. Army forts, succeeding in most cases, with the significant exceptions of Fort Jefferson, Fort Pickens and Fort Zachary Taylor, which stayed firmly in Federal control throughout the war.

_(14762345812).jpg.webp)

On January 6, 1861, state troops seized the Federal arsenal located in Chattahoochee.[50] On January 10, 1861, the day Florida declared its secession, Union general Adam J. Slemmer destroyed over 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg) of gunpowder at Fort McRee. He then spiked the guns at Fort Barrancas and moved his force to Fort Pickens. Braxton Bragg commanded the Battle of Pensacola.

On October 9, Confederates, including the 1st Florida Infantry, commanded by convention delegate James Patton Anderson, tried to take the fort at the Battle of Santa Rosa Island.[51] They were unsuccessful, and Harvey Brown planned a counter. On November 22, all Union guns at Fort Pickens and two ships, the Niagara and Richmond, targeted Fort McRee.[52] On January 1, there was an artillery duel in Pensacola. Twenty-eight gunboats commanded by Commodore Samuel Dupont occupied Fort Clinch at Fernandina Beach in March 1862. On March 11, the Union captured St. Augustine and Fort Marion. Before falling into Union hands, many ethnic Minorcans from St. Augustine, as well as other civilians, signed on as volunteers with a militia unit called the St. Augustine Blues. This company would eventually become a part of the 3rd Florida Infantry Regiment.[53]

Eastern Theater

As a result of Florida's limited strategic importance, the 2nd, 5th, and 8th Florida Infantries were sent to serve in the Eastern Theater in Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. They fought at Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville[54] and Gettysburg.

The 2nd Florida Infantry was first commanded by convention delegate G. T. Ward. He participated in the Yorktown siege, and died after being shot at the Battle of Williamsburg, the first battle of the Peninsula Campaign.

Richard K. Call's son-in-law Theodore W. Brevard Jr. was captain of the 2nd's Company D, the "Leon Rifles" at Yorktown and Williamsburg, leaving shortly after. Francis P. Fleming was a private in the 2nd. Convention delegate Thomas M. Palmer was the 2nd's surgeon.[55]

Roger A. Pryor commanded the 2nd during the Seven Days Battles. After Second Manassas, Pryor wrote “The Second, Fifth and Eighth (Florida) Regiments, though never under fire, exhibited the cool and collected courage of veterans."[56]

Delegate Andrew J. Lea was captain of the 5th's Company D. Delegates Thompson Bird Lamar and William T. Gregory served with the 5th at Antietam. Lamar was wounded and Gregory was killed.[57]

Perry's Florida Brigade

After Antietam, the 2nd, 5th, and 8th were grouped together under Brig. Gen. Edward A. Perry. Perry's Florida Brigade served in Anderson’s Division of the First Corps under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet.[58]

At Fredericksburg, the 8th regiment, whose Company C was commanded by David Lang protected the city from General Ambrose Burnside, contesting Federal attempts to lay pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River. An artillery shell fragment struck the chimney of the building that Lang occupied, and a large chunk of masonry struck him in the head, gravely injuring him. He was promoted to commander of the 8th.

After Chancellorsville, Perry was stricken with typhoid fever. Perry wrote "The firm and steadfast courage exhibited, especially by the Fifth and Second Florida Regiments, in the charge at Chancellorsville, attracted my attention."[56]

Lang took command of the Florida Brigade. The Florida Brigade served through the Gettysburg Campaign and twice charged Cemetery Ridge at Gettysburg, including supporting Pickett's Charge. It suffered heavy fire from Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery's line of artillery, and lost about 60% of its 700 plus soldiers when attacked on one flank by the 2nd Vermont Brigade of Brig. Gen. George J. Stannard.

Perry then returned to command of the Florida Brigade, leading it in the Bristoe and Mine Run campaigns.

The Florida Brigade took part in the Overland Campaign. Perry was wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness. The Brigade was then at the Battle of Cold Harbor. The 11th was then reorganized with Brevard as commander.

The Brigade then fought at the Siege of Petersburg. At Weldon Railroad, Brevard learned of the death of his brother, Mays Brevard. The Brigade also fought at the Battle of Ream's Station and the Battle of Globe Tavern. Lamar was shot off his horse by a Yankee sniper at Petersburg on August 30.[59]

Brevard was captured at the Battle of Sailor's Creek by General George Custer's cavalry.[60]

Western Theater

In early 1862, the Confederate government pulled General Bragg's small army from Pensacola following successive Confederate defeats in Tennessee at Fort Donelson and Fort Henry and the fall of New Orleans. It sent them to the Western Theater for the remainder of the war. Florida native Edmund Kirby Smith fought with Bragg.

The 1st and 3rd Florida Infantry Regiments joined Bragg in Tennessee. Convention delegate W. G. M. Davis raised the 1st Florida Cavalry and joined General Joseph E. Johnston in Tennessee. In December 1863, the 4th Florida Infantry was consolidated with the 1st Cavalry. Convention delegate Daniel D. McLean was a 2nd lieutenant in the 4th's Company H, and died in service. The 7th Florida Infantry also fought with the Army of Tennessee.

Engagements in Florida

Skirmish of the Brick Church

The first land engagement in Northeast Florida and first Confederate victory in Florida was the Skirmish of the Brick Church, fought by the 3rd Florida Infantry, commanded by convention delegate Col. William S. Dilworth.[61] Delegate Arthur J.T. Wright was an officer.[62]

After Bragg's troops left for Tennessee, the only Confederate forces remaining in Florida at that time were a variety of independent companies, several infantry battalions, and the 2nd Florida Cavalry, commanded by J. J. Dickison. On May 20, Confederates ambushed a Union landing party in Crooked River.

Tampa

The Union gunboat USS Sagamore sailed up Tampa Bay to bombard Fort Brooke under the command of John William Pearson on June 30, 1861. Representatives from both sides met under a flag of truce on a launch in the bay, where Pearson refused a Union demand that he unconditionally surrender. The Sagamore began bombarding the town that evening and the fort's defenders returned fire, opening the Battle of Tampa. The steamship moved out of range of the fort's guns the next morning and resumed fire for several hours before withdrawing. The engagement was inconclusive, as neither side scored a direct hit and there were no casualties.[63]

St. Johns Bluff

Jacksonville was occupied after the Battle of St. Johns Bluff, a bluff designed to stop the movement of Federal ships up the St. Johns River,[64] was won by John Milton Brannan and about 1,500 infantry.

The flotilla arrived at the mouth of the St. John' s River on October 1, where Cdr. Charles Steedman' s gunboats—Paul Jones, Cimarron, Uncas, Patroon, Hale, and Water Witch—joined them. Brannan landed troops at Mayport Mills. The Bluff held off the Naval squadron until the troops were landed to come up behind it, the Confederates quietly abandoned the work.

In January 1863, there was a skirmish at Township Landing with the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. On March 9, 1863, 80 Confederates were driven off by 120 men of the 7th New Hampshire Volunteers near St. Augustine.

On 28 July 1863, Sagamore and USS Para attacked New Smyrna.

Fort Brooke

The Battle of Fort Brooke in October 1863 was the second and largest skirmish in Tampa during the Civil War.[65] On October 15, two Union Navy ships, USS Tahoma and USS Adela, bombarded Fort Brooke from positions in Tampa Bay out of the range of Confederate artillery. Under the cover of shelling that continued intermittently for three days, a detachment of Union forces landed in secret and marched several miles to where two blockade running ships owned by former Tampa mayor James McKay Sr. were hidden along the Hillsborough River. The Scottish Chief, a steamship, and the sloop Kate Dale were burned at their moorings near present day Lowry Park. Their mission accomplished, Union troops made their way to their landing point but were intercepted near present day Ballast Point Park by a small force consisting of Confederate cavalry from Fort Brooke along with local militia. A brief but sharp skirmish erupted as the raiding party attempted to board their boats and row back to the Tahoma, with the ship supporting the troops in the water by firing shells over their heads at the Confederates on shore. Most of the landing party successfully returned to the ship and both sides suffered about 20 casualties.[63]

Tahoma returned to Tampa Bay and again shelled Fort Brooke on Christmas Day 1863. The defenders prepared for another landing but none was forthcoming, and the ship steamed away at nightfall.

By May 1864, all regular Confederate troops had been withdrawn from Tampa to reinforce beleaguered forces in more active theaters of war. Union forces landed without opposition on May 5 and seized or destroyed all artillery pieces and other supplies left behind at Fort Brooke. They occupied the fort for about six weeks, but as the town of Tampa had been largely abandoned, they left in June, leaving the fort unoccupied for the duration of the war.[63]

The force remaining in Florida were reinforced in 1864 by troops from neighboring Georgia. Andersonville Prison began in February 1864. Convention delegate John C. Pelot was its lead surgeon.

Olustee

Quincy Gillmore selected Brigadier General Truman Seymour for an invasion of Florida, landing in Jacksonville on February 7.[66] Joseph Finegan skirmished with Union forces at Barber's Ford and Lake City on February 10 and 11.[67] The only major engagement in Florida was at Olustee near Lake City.[68] Union forces under Seymour were repulsed by Finegan's Florida and Georgia troops and retreated to their fortifications around Jacksonville. Brevard's Battalion fought with Finegan's Brigade at Olustee.

.jpg.webp)

Seymour's relatively high losses caused Northern lawmakers and citizens to question the necessity of any further Union actions in militarily insignificant Florida. Many of the Federal troops were withdrawn and sent elsewhere. Throughout the balance of 1864 and into the following spring, the 2nd Florida Cavalry repeatedly thwarted Federal raiding parties into the Confederate-held northern and central portions of the state.

The Skirmish at Cedar Creek soon followed.[69] Perry had suffered wounds, and the three regiments of Perry's Brigade were consolidated into Finegan's Brigade, which included the 9th, 10th and 11th Infantries. Convention delegate Green H. Hunter was captain of the 9th's Company E. There was a skirmish at McGirt's Creek on March 1, 1864.

In March 1864, James McKay wrote the state to say he was unable to secure cattle as his blockade runners had been destroyed during the Battle of Fort Brooke. C. J. Munnerlyn organized the 1st Florida Special Cavalry Battalion or "Cow Cavalry" in April made up of Florida crackers, including John T. Lesley, Francis A. Hendry and W. B. Henderson.[70]

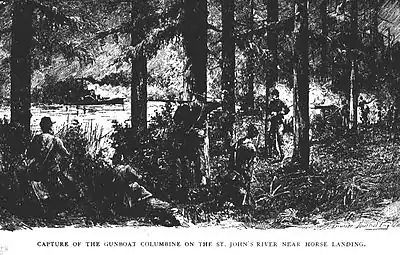

Horse Landing

Convention delegate James O. Devall owned General Sumpter, the first steamboat in Palatka, which was captured by USS Columbine in March 1864.[71] Palatka was occupied, and there were two picket attacks in late March. Union troops utilized Sunny Point, and St. Mark's was used as a barracks.

The first mine casualty of the war was Maple Leaf at Jacksonville on April 1, 1864.[72] General Hunter was sunk on April 16, close to where Maple Leaf was sunk.[73]

On May 19, there was a skirmish with the 17th Connecticut in Welaka, and a skirmish in Saunders. On May 21, spy Lola Sanchez got wind of a Union raid, and the Columbine was captured by Dickison's forces at the "Battle of Horse Landing".

New York's 14th cavalry lost in a skirmish at Cow Ford Creek on April 2. The 7th United States Colored Infantry fought in a skirmish at Camp Finnegan on May 25, and on the same day there was a skirmish at Jackson's Bridge near Pensacola.

Camp Milton was captured on June 2, and Baldwin raided on July 23. The Union would raid Florida's cattle. A skirmish at Trout Creek occurred on July 15. On July 24, William Birney was attacked by G. W. Scott and the 2nd Florida Cavalry at the South Fork of Black Creek.[74]

Gainesville

Confederates occupied Gainesville after the Battle of Gainesville.[75] On August 15, 1864, Col. Andrew L. Harris of the 75th Ohio Mounted infantry left Baldwin with 173 officers and men from the Seventy-Fifth Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The Union troops on the way destroyed a picket post on the New River. At Starke, the Union troops were joined by the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry and some Florida Unionists.[76] On August 17, 1864, Dickison was told that members of the Union Army had arrived at Starke and that they had burned Confederate train cars. Dickison proceeded to Gainesville, and attacked the Union troops from the rear.

Marianna

On September 27, 1864, General Alexander Asboth led a raid in Marianna, the home of Governor Milton and an important supply depot, and the Battle of Marianna ensued, with the Union stunned at first but achieving a victory.[77] Convention delegate Adam McNealy served in the Marianna Home Guard. Asboth was wounded, as was dentist Thaddeus Hentz, not far from his mother's grave, the famed novelist Caroline Lee Hentz, who wrote The Planter's Northern Bride, a pro-slavery rebuttal to Harriet Beecher Stowe's popular anti-slavery book, Uncle Tom's Cabin. The next day, Asboth's forces again ran into a battle in Vernon.

On October 18 at Pierce's Point south of Milton, Union troops were attacked by Confederates. In December 1864, there were skirmishes in Mitchell's Creek and Pine Barren Ford with the 82nd Colored Infantry.[78]

Braddock's Farm

Near Crescent City, there was the Battle of Braddock's Farm. Dickison caught the troops of the 17th Connecticut Infantry when they had just finished a raid, and when they charged, he shot their commander Albert Wilcoxson off his horse. When Dickison asked Wilcoxson why he charged, he responded, "Don't blame yourself, you are only doing your duty as a soldier. I alone am to blame."[79]

In Cedar Key, there was the Battle of Station Four.[80] The Battle of Fort Myers is known as the "southernmost land battle of the Civil War."[81] Confederate Maj. William Footman led 275 men of the "Cow Cavalry" to the fort under a flag of truce to demand surrender. The fort's commander, Capt. James Doyle, refused, and the battle began.

Natural Bridge

In March 1865 Battle of Natural Bridge, a small band of Confederate troops and volunteers, mostly composed of teenagers from the nearby Florida Military and Collegiate Institute that would later become Florida State University, and the elderly, protected by breastworks, prevented a detachment of United States Colored Troops from crossing the Natural Bridge on the St. Marks River.[82]

Surrender and immediate aftermath

On April 1, 1865 Governor Milton committed suicide rather than submit to Union occupation.[83] In a final statement to the state legislature, he said Yankees "have developed a character so odious that death would be preferable to reunion with them." He was replaced by convention delegate Abraham K. Allison.

Lang was again leading the Florida Brigade with Lee's army when it formally surrendered at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Johnston surrendered at Bennett Place on April 26, ending the war for the 89,270 soldiers in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

In early May 1865, Edward M. McCook's Union division was assigned to re-establish Federal control and authority in Florida. On May 13, G.W. Scott surrendered the last active Confederate troops in the state to McCook.

On May 20, General McCook read Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation during a ceremony in Tallahassee, officially ending slavery in Florida. That same day, his jubilant troopers raised the U.S. flag over the state capitol building. Tallahassee was the penultimate Confederate state capital to rejoin the Union. Austin, Texas, rejoined the next month.

Yulee was imprisoned for helping Jefferson Davis escape, and Lesley hid Judah Benjamin in a swamp before he fled to the Gamble Mansion.

Following the end of the Civil War, Florida was part of the Third Military District.[84]

Lewis Thornton Powell, a member of the Booth Conspiracy from Live Oak, was hanged in Washington and later buried in Geneva, Florida.[85]

Restoration to Union

After meeting the requirements of Reconstruction, including ratifying amendments to the US Constitution to abolish slavery and grant citizenship to former slaves, Florida's representatives were readmitted to Congress. The state was fully restored to the United States on June 25, 1868. Convention delegate E.C. Love was a leader in restoring the Democratic Party in Florida.[n 2]

Although the military forces in Florida were to leave on July 4, 1868 (following the restoration to the Union), Governor Reed requested the continuation of Union forces.[87] Almost nine years later, as part of the Compromise of 1877, in which Southern Democrats would acknowledge Republican Rutherford B. Hayes as president, Republicans agreed to meet certain demands. One such demand that affected Florida was the removal of all US military forces from the former Confederate states.[88] At the time, US troops remained in only Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, but the Compromise completed their withdrawal from the region.

Notes

- The Muscogee (Creeks) and other Indians were classified below the free people of color and above slaves.[3]

- His house still stands.[86]

References

- Civil War and Reconstruction - Florida Department of State. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- Robison, Jim (January 30, 2005). "Black Soldiers Played Proud Roles In Civil War Combat". Orlando Sentinel.

- Dysart, Jane (1982). "Another Road To Disappearance: Assimiliation of Creek Indians In Pensacola, Florida, During The Nineteenth Century". Florida Historical Quarterly. 61 (1): 37–48. JSTOR 30146156.

- Dodd, Dorothy (1945). "Florida in 1845". Florida Historical Quarterly. 24 (1): 3–27. JSTOR 30138575.

- "Eighth Census of the United States 1860 - Florida" (PDF). Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- Hindley, Meredith (November–December 2010). "The Man Who Came in Second". Humanities. 31 (6). Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- "Publications of the Florida Historical Society". Florida Historical Society. December 28, 2018. p. 104 – via Google Books.

- Wooster, Ralph (1957). "The Florida Secession Convention". Florida Historical Quarterly. 36 (4): 373–385. JSTOR 30139845.

- Ordinance of Secession. Florida Convention Of The People. 1861. LCCN 2021667639.

- Journal of the Proceedings of the Convention of the People of Florida. Tallahassee, Office of the Floridian and Journal, printed by Dyke & Carlisle. 1861. pp. 3–5. LCCN 16025843.

- Weitz, Seth A.; Sheppard, Jonathan C. (2018). A Forgotten Front: Florida During the Civil War Era. University of Alabama Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-8173-1982-3.

- Wynne, Nick; Knetsch, Joe (2014). On this Day in Florida Civil War History. Arcadia Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-62585-611-1.

- Florida, State Library and Archives of. "Civil War". Florida Memory. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- "Florida Secession". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- McConville, Michael (2012). The Politics Of Slavery And Secession In Antebellum Florida, 1845-1861 (Thesis).

- "Freedom First". February 2, 2006. Archived from the original on February 2, 2006.

- admin (February 18, 2016). "History of John C. McGehee".

- Underwood, Rodman L. (2005). Stephen Russell Mallory: A Biography of the Confederate Navy Secretary and United States Senator. McFarland. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-7864-2299-9.

- Spratt, Leonidas W. (October 5, 1903). "Deaths of the Day". Los Angeles Herald.

- "Florida Secedes from the Union". Museum of Florida History. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Reiger, John (1967). "Secession of Florida from the Union - A Minority Decision?". Florida Historical Quarterly. 46 (4): 358–368. JSTOR 30147281.

- Josh. "Richard Keith Call Collection Now Online at Florida Memory". Archived from the original on April 25, 2014.

- Barnhardt, Luther Wesley (1922). The Secession Conventions of the Cotton South. University of Wisconsin--Madison. p. 51.

- Florida, State Library and Archives of. "Presentation of Confederate Battleflag to Family of Colonel George T. Ward, 1862". Florida Memory. Archived from the original on December 22, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- "Today in History - January 10". Library of Congress.

- Waters, Zack C. (2013). A small but spartan band : the Florida brigade in Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. Tuscaloosa, AL.: University Alabama Press. p. 7. ISBN 9780817357740.

- Davis, William C. (2002). "Men but Not Brothers". Look Away!: A History of the Confederate States of America. Simon and Schuster. pp. 130–162. ISBN 978-0-7432-2771-1.

- Redd, Robert (2014). St. Augustine and the Civil War. Arcadia Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-62584-657-0.

- "Travel Back in Time to 1860" (PDF). Forum. Vol. 34, no. 1. Florida Humanities Council. Spring 2010. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 1, 2019.

- Bittle, George C. (October 1972). "Florida Prepares for War, 1860-1861". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 51 (2): 144. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- Revels, Tracy J. (2016). Florida's Civil War: Terrible Sacrifices. Mercer University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-88146-589-1.

- Reiger, John F. (January 1970). "Deprivation, Disaffection, and Desertion in Confederate Florida". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 48 (3): 279. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- Florida Memory. "Needs More Salt". www.floridamemory.com. State Library and Archives of Florida. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- Brown Jr., Canter (April 1992). "Tampa's James McKay and the Frustration of Confederate Cattle-Supply Operations in South Florida". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 70 (4): 411. Retrieved February 17, 2023.

- Cortada, James (1980). "Florida's Relations with Cuba During the Civil War". Florida Historical Quarterly. 59 (1): 42–52.

- "Civil War Raids & Skirmishes in 1862". www.mycivilwar.com.

- Buker, George E. (1986). Fretwell, Jacqueline K. (ed.). Civil War Times in St. Augustine. St. Augustine Historical Society. pp. 5–9. ISBN 0912451238.

- Solomon, Irvin (1998). "Race And Civil War In South Florida". Florida Historical Quarterly. 77 (3): 320–341. JSTOR 30147583.

- Nelson, Bernard H. (October 1946). "Confederate Slave Impressment Legislation, 1861-1865". The Journal of Negro History. 31 (4): 394. doi:10.2307/2715214. JSTOR 2715214. S2CID 149502188. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- Murphree, R. Boyd. "Florida and the Civil War: A Short History". Florida Memory.

- Taylor, Robert (1990). "Unforgotten Threat: Florida Seminoles in the Civil War". Florida Historical Quarterly. 69 (3): 300–314. JSTOR 30147523.

- Shull, Hugh (December 2006). A Guide Book of Southern States Currency. Atlanta, GA: Whitman Publishing LLC. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9780794822330.

- Beals, Carleton (1965). War Within a War; the Confederacy Against Itself (1st ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Chilton Books. pp. 69–70.

- Cash, W.T. (1948). "Taylor County History and Civil War Deserters". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 27 (1): 49–52. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- Solomon, Irvin D. (October 1993). "Southern Extremities: The Significance of Fort Myers in the Civil War". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 72 (2): 129–152.

- Revels 2016, p. 2.

- Coles, David J.; Ferry, Richard J.; Baldwin, Robert (January–February 1993). ""The Smallest Tadpole": Florida in the Civil War". Military Images. 14 (4): 6. JSTOR 44032489. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- Taylor, R. A. (1991). ""Unforgotten Threat: Florida Seminoles in the Civil War"". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 69 (3): 300–314. JSTOR 30147523.

- Porter, Kenneth W. (April 1967). "Billy Bowlegs (Holata Micco) in the Civil War (Part II)". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 45 (4): 392. Retrieved August 18, 2023.

- The War of the Rebellion : a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate armies. Washington D.C.: United States War Department. 1880–1901. p. 332. Retrieved August 13, 2022.

- "October 9, 1861". Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- "Pensacola - Early Civil War Union Victory". exploringoffthebeatenpath.com.

- Weitz, Seth A.; Sheppard, Jonathan C., eds. (2018). A Forgotten Front: Florida during the Civil War Era. University Alabama Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0817319823.

- Luvaas, Jay; Nelson, Harold W., eds. (1988). The U.S. Army War College guide to the Battles of Chancellorsville & Fredericksburg (1st ed.). Carlisle, Pa.: South Mountain Press. p. 326. ISBN 0937339024.

- "Palmer Family Graveyard and Palmer-Perkins House in Monticello, FL". Visit Florida.

- "Museum of Southern History_Floridians in Virginia".

- "Antietam: Capt William T. Gregory". antietam.aotw.org.

- Hawk, Robert (1986). Florida's army: militia, state troops, National Guard, 1565-1985. Pineapple Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-910923-34-7. OCLC 14376703.

- "Antietam: LCol Thompson Bird Lamar". antietam.aotw.org.

- Dickinson, J.J. (1899). "Military History of Florida" (PDF). In Evans, Cement Anslem (ed.). Confederate military history; a library of Confederate States history. Vol. 11. Atlanta: Confederate Publishing Co. p. 160.

- "Lost Church, Lost Battlefield, Lost Cemetery, Lost War - Metro Jacksonville". www.metrojacksonville.com.

- Sheppard, Jonathan C. (2012). By the Noble Daring of Her Sons: The Florida Brigade of the Army of Tennessee. University of Alabama Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8173-1707-2.

- Waters, Zack (March 13, 2018). "Tampa's Forgotten Defenders: The Confederate Commanders of Forte Brooke". Sunland Tribune. 17 (1).

- "October 1–3, 1862". Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- "Florida Battle at Fort Brooke American Civil War". www.americancivilwar.com.

- "Battle of Olustee - Events Leading up to the Battle of Olustee". battleofolustee.org.

- Hewitt, Lawrence L.; Bergeron, Arthur W. (2011). Confederate Generals in the Western Theater, Vol. 3: Essays on America's Civil War. Univ. of Tennessee Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-57233-790-9.

- "Battle of Olustee Facts & Summary". American Battlefield Trust. January 13, 2009.

- "The Museum of Southern History". March 3, 2009. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009.

- Taylor, Robert (1986). "Cow Cavalry: Munnerlyn's Battalion in Florida, 1864-1865". Florida Historical Quarterly. 65 (2): 196–214. JSTOR 30146741.

- Gaske, Frederick P. (2011). Florida Civil War Heritage Trail (PDF). Department of State, Division of Historical Resources. ISBN 978-1-889030-22-7.

- Rob, Seaman (April 6, 2014). "Civil War Navy Sesquicentennial: Sinking of the Union transport steamer Maple Leaf".

- "This Day in the American Civil War for April 16". Archived from the original on July 24, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- Gladwin, William J. (June 1992). "Men, Salt, Cattle and Battle: The Civil War in Florida (November 1860-July 1865)" (Document). Naval War College (Newport, RI). DTIC ADA255006.

- "Gainesville, Florida Civil War site photos". www.civilwaralbum.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- "The Battle of Gainesville". exploresouthernhistory.com. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- The Battle of Marianna Archived 2013-11-10 at the Wayback Machine

- "Florida Battles - The Civil War (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

- Dickison, Mary Elizabeth (1890). Dickison and His Men: Reminiscences of the War in Florida. Courier-Journal Job Printing Company. p. 123.

- "Cedar Key, Florida Civil War site photos". www.civilwaralbum.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- "Battle of Fort Myers, FL site photos". www.civilwaralbum.com. Archived from the original on November 22, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- "Battle of Natural Bridge Facts & Summary". American Battlefield Trust. December 19, 2008.

- "Florida Governor John Milton". National Governors Association. Archived from the original on December 9, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- Cox, Merlin (1967). "Military Reconstruction in Florida". Florida Historical Quarterly. 46 (3): 219–233. JSTOR 30147764.

- "Biography and Images of Lewis Powell, Assassination Conspirator". law2.umkc.edu. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- admin (October 20, 2015). "HISTORIC HOMES". dosomethingoriginal.com. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- Leonard, M. C. Bob. "Florida in the Civil War". Florida History Internet Center. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- Woodward, C. Vann (1966). Reunion and Reaction: The Compromise of 1877 and the End of Reconstruction. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. pp. 169–171.

Further reading

- Brown, Canter. Tampa in Civil War & Reconstruction, University of Tampa Press, 2000. ISBN 978-1-879852-68-6.

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Johns, John Edwin. Florida During the Civil War (University of Florida Press, 1963)

- Murphree, R. Boyd. "Florida and the Civil War: A Short History". Florida Memory.

- Nulty, William H. Confederate Florida: The Road to Olustee (University of Alabama Press, 1994)

- Taylor, Paul. Discovering the Civil War in Florida: A Reader and Guide (2nd edition). Sarasota, Fl. Pineapple Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1-56164-529-9

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 70 volumes in 4 series. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1880-1901.

External links

- Cannonball at A History of Central Florida Podcast

- Florida and the Civil War, open access digital collection of materials from the PK Yonge Library of Florida History

- Florida Memory Project - State Archives

- National Park Service map of Civil War sites in Florida Archived February 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Journal of the Secession Convention

.svg.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)