Fort Foote

Fort Foote was an American Civil War-era wood and earthwork fort that was part of the wartime defenses of Washington, D.C., which helped defend the Potomac River approach to the city. It operated from 1863 to 1878, when the post was abandoned, and was used briefly during the First and Second World Wars. The remnants of the fort are located in Fort Foote Park, which is maintained by the National Park Service as part of the National Capital Parks-East system. The area's mailing address is Fort Washington, Maryland.

| Fort Foote | |

|---|---|

| Prince George's County, Maryland | |

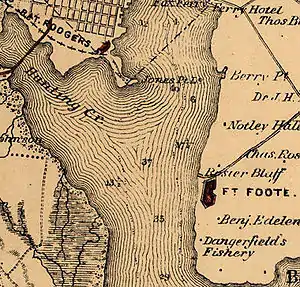

This drawing of Fort Foote shows a view of the fort looking to the east from above the Potomac River. Much of the interior buildings can be distinguished, as can the two sites of the Rodman guns mounted at the fort. | |

Fort Foote  Fort Foote | |

| Coordinates | 38°46′00″N 77°01′40″W |

| Type | Earthwork fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner | National Park Service |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Partially preserved, multiple guns at site |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1863 |

| Built by | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1863–1878 |

| Materials | Earth, timber |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | 9th New York Heavy Artillery, others |

| Fort Foote Park | |

|---|---|

| Location | Prince George's County, Maryland, U.S. |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

Planning

In the opening days of the American Civil War, the defenses of Washington D.C. were primarily concerned with an overland attack on the capital city of the United States. In 1861, the Arlington Line was constructed to help defend the city from attack via the direct, Virginia approach. Additional forts were constructed on the city's northern approaches to defend against any attacks from Maryland. At sea, however, only Fort Washington, a fort originally built to defend the city in the War of 1812 blocked the approach along the Potomac River.[1]

Fort Washington's vulnerability was highlighted in the 1862 clash of the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia, two wholly ironclad ships. Although the Virginia never attacked Union ships again, Washingtonians were concerned that an ironclad similar to the Virginia might be able to slip past the isolated guns of Fort Washington and begin a bombardment of the city. They were also concerned with the potential intervention of European nations on the side of the Confederacy, possibly adding a major naval threat to the city.[2] A commission appointed by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton to examine the defenses of Washington came to the conclusion that although sufficient defensive works had been constructed in order to defend the city from land attack, the city was still vulnerable to attack from the water.

The commission furthers their opinion that the Defense of Washington cannot be considered complete without the defense of the river against an enemy's armed vessels. Foreign intervention would bring against us always in superior naval force on the Potomac, and we are, even now, threatened with Confederate iron-clads fitted in English Ports. ...and by constructing a battery of ten guns and a covering work on the opposite shore of the Potomac, at [or] near Roziers Bluff [the situation can be remedied]. An examination [has] been made, revealing a most favorable and strong position on that side, easily communicated with by water. Surveys are in progress.[3]

Then-colonel John Gross Barnard, the chief military engineer for the defenses of Washington, went to work on the commission's recommendation with haste. Rosiers Bluff, a 100-foot (30 m) high Maryland cliff six miles (10 km) south of the city, and pointed out in the commission's report was found to be an excellent site for the new fort.[2] The layout would largely follow the plans laid out in West Point instructor Dennis Mahan's A Treatise on Field Fortification, which said

As a field fort must rely entirely on its own strength, it should be constructed with such care that the enemy will be forced to abandon an attempt to storm it, and be obliged to resort to the method of regular approaches used in the attack of permanent works. To effect this, all the ground around the fort, within range of the cannon, should offer no shelter to the enemy from its fire; the ditches should be flanked throughout; and the relief be so great as to preclude any attempt at scaling the work.[4]

Construction

Construction began in the winter of 1862–1863, but progressed slowly. Initial difficulties in obtaining labor for the construction were resolved with the arrival of four companies of soldiers in August, 1863.[5] By fall, the fort was pronounced complete, and was certified ready for action. Due to its location along the coast, the use of iron in the fortifications was limited, and most of the fort was constructed of earth and locally cut lumber.

"The revetments of breast-height and slopes, and all the vertical walls of the interior structure, as magazines, bomb-proofs, galleries, &c., were made almost wholly of cedar posts, while the roofing of these structures were mainly of chestnut logs," General Barnard wrote in an 1881 report on the defenses. The portion of the fort that faced the Potomac was over 500 feet (150 m) long with earth walls approximately 20 feet (6 m) thick. A central traverse ran the length of the fort and contained bombproof magazines and storage areas for the eight 200-pounder Parrott rifles and two 15-inch Rodman guns contained in the fort.[6]

The guns themselves came in dribs and drabs, due to delays in casting and the demands of guns needed for combat in Virginia. The first 15-inch Rodman gun arrived in late 1863, and others arrived at various points over the next two years. The fort was not completely armed until April, 1865, just before the final surrender of Confederate forces in Virginia, and was not pronounced complete until June 6, 1865. In that month, Fort Foote boasted two 15-inch Rodman guns, four 200-pounder Parrott rifles, and eight 30-pounder Parrott rifles.[2]

Operation

In 1863, even as the walls of the fort rose above the cliffs of Maryland, the first unit of the fort's garrison arrived in Maryland. The four companies of the 9th New York Heavy Artillery Regiment were immediately pressed into service as laborers on the construction project. They were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William H. Seward Jr., son of the U.S. Secretary of State William Seward. On August 20, 1863, Seward, President Abraham Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and the recently promoted General Barnard visited the new construction.[7] Due to the close proximity of the fort to Washington and the fact that his son was stationed there, Secretary Seward was a frequent visitor to Fort Foote.

One month after the Presidential visit, on September 17, 1863,[8] the fort was named in honor of Admiral Andrew H. Foote, by Secretary Seward, who attended the naming ceremonies as the guest of honor.[7] As a Flag Officer, Foote was the commander of the Mississippi River Squadron and led the naval assault on Fort Donelson, which controlled access to the Cumberland River. During the course of the battle, Foote was severely wounded. After spending several months recuperating in New York City, Foote was named commander of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. En route to assuming command, he died of complications from his wounds on June 26, 1863. In recognition of his achievements during the war, the fort under construction along the Potomac was named in his honor.[9][10]

Daily life

Daily life at Fort Foote was similar to that experienced by soldiers at other forts in the Washington defenses. A soldier's normal day began with reveille before sunrise and was immediately followed by morning muster, at which the soldiers of the garrison were counted and reported for sick call. Following muster, the day was filled with work on improving the fort's defenses and drill of various types, usually gunnery practice or parade drills. These usually continued, broken by meal and rest breaks, until taps was called at 8:00 or 9:00 p.m. Sunday was a break in the routine as the muster was immediately followed by a weekly inspection and church call. Sunday afternoons were a soldier's free time, and this was usually filled by writing letters home, bathing, or simply catching up on extra sleep.

Although Fort Foote was within sight of the city lights of Washington, it was still considered an isolated post and the ordinary troops on duty were some distance from the nightlife offered by the city. The nearest land route, Piscataway Road, was over a mile away and was used only when the Potomac froze over and ended water traffic. Nearly all communication with Fort Foote was by the river wharf at the bottom of the bluff that was completed in 1864. A mail boat stopped at the fort three times a week, and there were daily boats to Alexandria and Washington, but these were exclusive to officers, visitors, and other VIPs. Ordinary soldiers were rarely granted a furlough to Alexandria, which lay just across the river, or to Washington, six miles (10 km) distant.

Unlike most seacoast fortifications, which housed their garrisons within the walls of the fort, the garrison at Fort Foote lived in wood-frame buildings outside the confines of the fort. Despite this relative luxury, duty at Fort Foote was considered unpleasant and possibly hazardous. A large swamp surrounded Rosier's Bluff, and mosquitoes plagued the post with malaria during the summer. In addition, the lack of easily obtained pure water made typhoid a constant threat. At any given time during the summer, as much as half the garrison would be on the sick list, filling the 10-by-40-foot hospital to its seams.[2]

Special occasions

Due to the relative closeness of Fort Foote to Washington and the enormous size of its guns — the largest defending Washington — every regularly scheduled gunnery was attended by Washington residents, many of whom were prominent citizens. On February 27, 1864, a large crowd of Washingtonians attended the inaugural firing of the fort's 15-inch (381 mm) guns. The enormous smoothbore cannons weighed 25 tons and required forty-five pounds of powder to send a 440-pound round-shot over 5,000 yards (5,000 m). By virtue of their need to potentially face ironclad warships, they were far larger than any guns defending Washington from the land. The festive February scene was again repeated on April 1, 1864, when the 15-inch (381 mm) guns were fired once more.[2]

Secretary Seward and his wife were regular visitors to the fort during the summer of 1864, often coming out to watch the fort's demonstrations and often bringing parties of distinguished visitors. On one scheduled occasion, the Sewards attended a training drill at which the fort's gunners were to use a target anchored in the middle of the Potomac, two miles (3 km) away. Confederate sympathizers, having learned of the scheduled target practice, rowed out from the Virginia shore, cut the target loose, and towed it away. The embarrassed Union gunners were forced to fire on alternative targets while Mrs. Seward conducted an impromptu lunch in one of the fort's bunkers.[7]

On October 22, 1864, the Sewards again returned to the fort, this time with U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, U.S. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Wells, and General Barnard in tow. The visit was intended to commemorate the first firing of the fort's new 200-pounder Parrott rifles. By this time, however, the Civil War was beginning to wind down and Washingtonians were beginning to question the post-war usefulness of the forts that protected Washington. Said Secretary Wells,

It is a strong position and a vast amount of labor has been expended—uselessly expended. In going over the works a melancholy feeling came over me, that there should have been so much waste, for the fort is not wanted, and will never fire a hostile gun. No hostile fleet will ever ascend the Potomac.[7]

Post-War use

With Robert E. Lee's surrender on April 9, 1865, Secretary Wells's words proved to be prophetic. Fort Foote never fired a shot in anger against any opponent, Confederate or otherwise. With the end of the war, the federal government began turning over Washington's forts and the land on which they rested to their pre-war owners. In a few cases, the federal government chose to retain possession. Fort Foote was one of those exceptions. New construction was required to fulfill its role as a federal prison, which it performed between 1868 and 1869.

In addition to the prison, the fort was also used as a testing ground for a recoil gun carriage. In 1869, Major W. R. King set up a 15-inch (381 mm) gun and began experimenting. During the first trials of the new setup, he fired 22 rounds from a 15-inch (381 mm) gun with charges ranging from 25 to 100 pounds. Though initially successful, testing was suspended due to the difficulty in obtaining a free lane of fire. With the coming of peace, commercial traffic had returned to the Potomac, and firing 400-pound cannonballs over the heads of steamer captains was frowned upon for safety reasons. In addition, the gun proved to be too powerful for the limited confines of the Potomac. With his testing hampered by local conditions, Major King moved his experiment to Battery Hudson in New York in 1871.[2]

In 1872, plans to strengthen the fort were submitted by the War Department and as a first step, the federal government purchased the fort's land outright from its previous owner in 1873 rather than continuing the wartime lease. Work began on the new improvements, but when the appropriation was abruptly withdrawn, construction halted. With continued post-war military cutbacks, the garrison was removed in 1878 and the fort was abandoned.

Between 1902 and 1917, it was used as a training area for a local engineering school. During this time, the fort's now-obsolete guns were removed, with the exception of the two 15-inch cannons and a Parrott rifle that was sent to a cemetery in Pennsylvania. During the First World War, the fort was used for gas service training, and during the Second World War, the site was used by officer candidates from Fort Washington. After that war, the fort was transferred to the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service for inclusion in the Service's system of DC-area national parks.[2]

Bicentennial Park plans

In the 1960s, a number of different plans were proposed to create a new museum park on the site of Fort Foote. A "National Armed Forces Museum Advisory Board of the Smithsonian Institution" was authorized in 1961 and in 1966, a National Armed Forces Museum was proposed.[11] However, the political climate and the Vietnam War becoming more unpopular worked against these plans, as critics questioned the wisdom of what would be seen as a war museum.[12]

As a result, the advisory board revised the plan to propose Bicentennial Park,[13] a combination museum and park by the Smithsonian Institution and National Park Service.[14] In January 1967, the choice of using Fort Foote was approved by the National Capital Planning Commission. Plans for the park included a recreation of a Revolutionary War encampment. Planners wrote, "emphasis will be placed on the every- day camp life of the patriot man-at-arms, on the long and patient labor, the sacrifice, and the self-reliance demanded in the struggle to bring forth the first modern republic." The park was to include the encampment, a parade ground and a primitive fort made of wood and staffed by period reenactors. There was also to be a Naval Ordnance Park along the riverbank.[12]

However, securing the Fort Foote site became a problem because of local opposition. The National Bicentennial Commission also ensured the park's demise when it said it had “limited relevance and significance.” By 1973, the effort to create a park on the site of Fort Foote had failed.

Modern use

The area that once held the fort is largely forested, though some of the original bastions have been preserved. Two 15-inch (381 mm) guns sit on carriages overlooking the Potomac. Only one was originally used at Fort Foote. The other is from Battery Rodgers, which lay on the opposite side of the river during the Civil War.

References

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, III, Symbol, Sword, and Shield: Defending Washington During the Civil War, Second Edition Revised (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, 1991)

- "Fort Foote Park: History & Culture". National Park Service. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- "Civil War Defenses of Washington: Fort Foote". National Park Service. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- Mahan, Dennis Hart, A Treatise on Field Fortification, Containing Instructions on the Method of Laying Out, Constructing, Defending, and Attacking Intrenchments, With the General Outlines Also of the Arrangement, the Attack, and Defence of Permanent Fortifications, Third Edition, Revised and Enlarged (New York: John Wiley, 1863), 17.

- "Chapter 4: The Civil War Years", in Civil War Defenses of Washington, Historic Research Study, retrieved 2009-04-05

- "Fort Foote", Civil War Defenses of Washington, National Park Service, retrieved April 5, 2009

- "The Marvel of the Big Guns at Fort Foote", in Civil War Defenses of Washington, National Park Service, retrieved 2009-04-05

- General Orders No.313

- Foote, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Naval Historical Center, retrieved 2009-04-05

- Letter, Gen. J.G. Barnard to Col. J.C. Kelton, Sept. 4, 1863, in Civil War Defenses of Washington, Historic Research Study, Appendix C: Naming the Forts, retrieved 2009-04-05

- House, United States Congress (1967). Hearings. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Allison, David K.; Peterson, Hannah (February 18, 2021). Exhibiting America: The Smithsonian's National History Museum, 1881–2018. A Smithsonian Contribution to Knowledge. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press. doi:10.5479/si.13623881.v1. ISBN 978-1-944466-40-4. S2CID 233907237.

- "Proposal for the Bicentennial Park and Armed Forces Museum - Smithsonian Institution Collections Search Center". collections.si.edu. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- Bennett, William (August 25, 2016). "The National Park that Never Was". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

External links

- Fort Foote Park – National Park Service website