Fortifications of Gibraltar

The Gibraltar peninsula, located at the far southern end of Iberia, has great strategic importance as a result of its position by the Strait of Gibraltar where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean. It has repeatedly been contested between European and North African powers and has endured fourteen sieges since it was first settled in the 11th century. The peninsula's occupants – Moors, Spanish, and British – have built successive layers of fortifications and defences including walls, bastions, casemates, gun batteries, magazines, tunnels and galleries. At their peak in 1865, the fortifications housed around 681 guns mounted in 110 batteries and positions, guarding all land and sea approaches to Gibraltar.[1] The fortifications continued to be in military use until as late as the 1970s and by the time tunnelling ceased in the late 1960s, over 34 miles (55 km) of galleries had been dug in an area of only 2.6 square miles (6.7 km2).

| History of Gibraltar |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

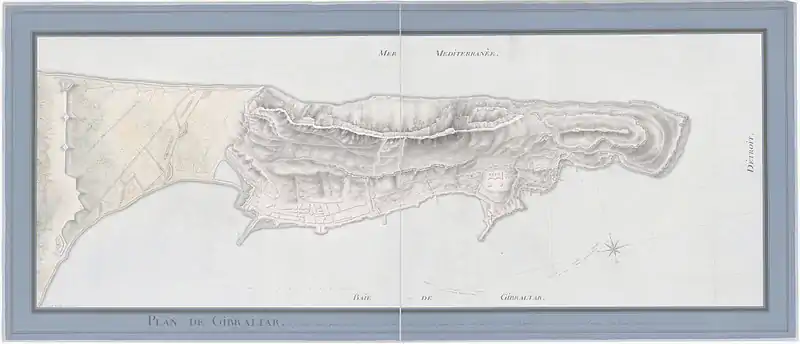

Gibraltar's fortifications are clustered in three main areas. The densest fortifications are in the area where historically Gibraltar was under the most threat – at the north end of the peninsula, the North Front, facing the isthmus with Spain. Another group of fortifications guards the town and the harbour, referred to as the West Side. The southern end of the town is guarded by the South Land Front. Few fortifications exist on the east side, as the sheer cliff of the Rock of Gibraltar is a virtually impassable obstacle. Further fortifications occupy the plateaus of Windmill Hill and Europa Point at the southern end of the peninsula. Lookout posts and batteries on the summits of the Rock provide a 360° view across the Strait and far into Spain. Although Gibraltar is now largely demilitarised, many of the fortifications are still intact and some, such as the Great Siege Tunnels and the Charles V Wall – where many of Gibraltar's population of Barbary macaques live – have become tourist attractions.

Topography

The nature and position of Gibraltar's defences have been dictated by the territory's topography. It is a long, narrow peninsula measuring 5.1 kilometres (3.2 miles) by 1.6 kilometres (1 mile) wide at maximum, with a land area of about six square kilometres (2.3 square miles). The only land access to the peninsula is via a sandy isthmus, only three metres (9.8 feet) above sea level, most of which is now occupied by the Spanish town of La Línea de la Concepción. The peninsula is dominated by the limestone massif of the Rock of Gibraltar, which presents a sheer cliff over 400 metres (1,300 feet) high at its north end, facing the isthmus. The Rock extends southwards for 2.5 kilometres (1.6 miles) with several peaks before it descends to two southern plateaus at heights of between 90–130 metres (300–430 feet) and 30–40 metres (98–131 feet) above sea level. The southern tip of Gibraltar is surrounded by steep cliffs. The Rock itself is asymmetric, with a moderate slope on the west side and a very steep (and in places near-vertical) slope on the east side. The original core of the town of Gibraltar occupies the lower north-west side of the Rock, adjoining the Bay of Gibraltar, though it has grown considerably to the point that the built-up area now stretches all the way to Europa Point on the southern tip of the peninsula. A great deal of 20th century land reclamation on the west side has also widened the coastal area, which was formerly quite narrow. A couple of small settlements, originally fishing villages, occupy the east side.[2]

These features have made Gibraltar a naturally strong defensive position. The isthmus lacks any natural cover, exposing any approaching enemy to opposing fire. The heights of the Rock form a natural barrier to movement and rocky ledges provide natural platforms for gun batteries. The sheer cliffs on the north and east sides of the Rock block access from those directions and the sea cliffs around the southern end of the peninsula make landings there difficult, especially if opposed.[3] A single road connects Gibraltar with Spain, and within the territory most roads are narrow and often steep due to the restricted land area.[4] Over the centuries, Gibraltar's successive occupants have built an increasingly complex set of fortifications around, on top of and incorporating the territory's natural features.[3]

Writing in 1610, the Spanish historian Fernando del Portillo commented that Gibraltar was "a stronghold from its very topography which with a little art could be made impregnable," and so it has proved.[5] The Irish writer George Newenham Wright observed in 1840 that "the surface of the Rock is wholly occupied by defensive works; where it was possible, and often where it appeared almost impracticable, batteries and fortifications have been formed. From Europa Point, which pushes into the sea on the south side, to the highest point of the Rock, there is not a single point that has not been put into a defensible condition . . . Proceeding towards Europa Point, at the entrance of the town, fortifications, magazines, barracks, and batteries are placed wherever the nature of the surface would permit."[6]

History

Moorish period

Gibraltar's fortifications have evolved in a number of stages. Its first permanent inhabitants, the Moors of North Africa, are said to have established a fort on Djebel Tarik (the Mount of Tarik, a name that was eventually corrupted into Gibraltar) "to be on guard and watch events on the other side of the Straits" as early as 1068.[7] Gibraltar was fortified for the first time in 1160 by the Almohad Sultan Abd al-Mu'min in response to the coastal threat posed by the Christian kings of Aragon and Castile. The Rock of Gibraltar was renamed Jebel al-Fath (the Mount of Victory), though this name did not persist,[8] and a fortified town named Medinat al-Fath (the City of Victory) was laid out on the upper slopes of the Rock.[9] It is unclear how much of Medinat al-Fath was actually built, as the surviving archaeological remains of Moorish Gibraltar are scanty.[10] A portion of wall some 500 metres (1,600 ft) long still survives to the south of the main part of the city of Gibraltar, of similar design to defensive walls in Morocco. It may have protected a settlement on the upper part of the Rock, around where the modern Queen's Road is, but firm archaeological evidence is lacking.[11]

The city fell to the Castilians in 1309 after the first siege of Gibraltar and its fortifications were repaired and improved by King Ferdinand IV of Castile, who ordered the construction of a keep above the town.[12] The Castilians maintained control of Gibraltar until 1333, resisting a Moorish siege in 1315, but relinquished it in 1333 after the third siege of Gibraltar. After defeating a Castilian counter-siege which ended after two months, the Marinid sultan Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn Othman ordered a refortification of Gibraltar "with strong walls as a halo surrounds the crescent moon".[13] Many details of the rebuilt city are known due to the work of Abu al-Hasan's biographer, Ibn Marzuq, whose Musnad (written around 1370–71) describes the reconstruction of Gibraltar. The city was expanded, and a new defensive wall was built to cover the western and southern flanks, with towers and connecting passages added to strengthen them. The existing fortifications were also strengthened and repaired. The weak points that the Castilians had exploited were improved.[9]

- Inner and outer keep

- Qasbah

- Villa Vieja

- Port (Barcina)

- Tower of Homage

- Flanking Wall

- Gate of Granada

- Gatehouse

- Tower

- Giralda Tower (North Bastion)

- Landport

- Sea Gate (Grand Casemates Gates)

- Barcina Gate

- Galley House

The refortified city occupied the north-eastern part of the present-day city, reaching from the area of Grand Casemates Square up to Upper Castle Road. It was divided into three main quarters which functioned as a series of baileys through which troops could fall back in stages. The Tower of Homage (now usually called the Moorish Castle, though more properly that name refers to the entire fortified area of the Moorish city) was located at the highest point, serving as a final redoubt. The Tower was a formidable square keep situated within a kasbah and had the largest footprint of all the towers to be built in Moorish Al-Andalus (320 square metres (3,400 sq ft)).[14] It was a much-strengthened rebuilding of an earlier tower and still bears scars on its eastern wall from projectiles shot by the Castilians during the siege of 1333.[13] The kasbah could only be accessed via a single gate, which still survives; an inscription visible up to the 18th century recorded that it had been dedicated to Yusuf I, Sultan of Granada.[15]

Below the kasbah was an area later called the Villa Vieja (Old Town) by the Spanish, accessed via the Bab el-Granada (Granada Gate), and below that was a port area called La Barcina by the Spanish, which may have taken its name from the Galley House (Arabic: Dar el-Sinaha) built there by the Moors.[16] It had three separate access gates: the Land Gate (now the Landport Gate), the Sea Gate (now the Grand Casemates Gates) and a southern gate, the Barcina Gate.[14] The core of the city was surrounded by substantial defensive walls with tall towers topped by merlons.[17] Other than the Tower of Homage, two such towers still survive; one square based which was fitted with a clock in Victorian times (now the Stanley Clock Tower)[18] and another constructed en bec (beaked, a design intended to resist mining).[19] The walls were at first built using tapia, a lime-based mortar made with the local sand and faced with decorative brickwork to simulate masonry. The builders later changed their construction methods to utilise stone interlaced with brick, a rather stronger structure. The southern flank of the walls has survived relatively intact, and vestiges of the other walls are most likely still to be found underlying the modern defensive walls constructed by the British.[15] To the south of the fortified city was an urban area known as the Turba al Hamra, literally the "red sands", named after the predominant colouration of the soil in that area.[14] Ibn Battuta visited the city in 1353–54 and wrote:

I walked round the mountain and saw the marvellous works executed on it by our master, the late Sultan of Morocco, and the armament with which he equipped it, together with the additions made thereto by our master Abu Inan, may God strengthen him ... [He] strengthened the wall of the extremity of the mount, which is the most formidable and useful of its walls.[20]

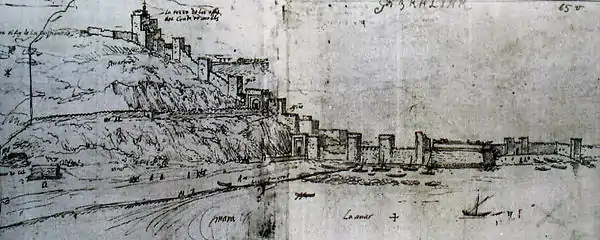

Spanish period

Castile regained control of Gibraltar in the Eighth Siege of 1462.[21] The Moorish threat receded following the completion of the Reconquista and the fortifications were allowed to fall into decay, with very few cannon mounted on the batteries.[22] In 1535, the Spanish naval commander Álvaro de Bazán the Elder warned King Charles I that Gibraltar's defences were seriously inadequate and recommended that the Line Wall Curtain be extended all the way to Europa Point on the southern tip of Gibraltar and that the town's southern wall should be strengthened. However, his advice was ignored.[23] The soldier and writer Pedro Barrantes Maldonaldo noted that by 1540 Gibraltar's north-west bastion (presumably referring to North Bastion) had only four guns, while the castle's few guns were all dismounted (and therefore unusable), and there were no gunners. The garrison's equipment was antiquated and their numbers were few. The town's walls were still essentially medieval and could not have resisted mid-16th century artillery. The fall of Constantinople 90 years earlier showed just how vulnerable such walls could be in the face of a heavy artillery bombardment.[24]

The town's inhabitants paid the price for this neglect in September 1540 when Barbary pirates from North Africa carried out a major raid, taking advantage of the weak defenses. Hundreds of Gibraltar's residents were taken as hostages or slaves. The Spanish crown responded to Gibraltar's vulnerability by building the Charles V Wall to control the southern flank of the Rock. The wall's builder, the Italian engineer Giovanni Battista Calvi, also strengthened the Landport Gate. Another Italian engineer, Giovan Giacomo Paleari Fratino, extended the wall onto the Upper Rock at some point probably between 1558–65.[25] A lookout tower, one of several constructed along Spain's southern coast during this period, was built at the eastern end of the isthmus linking Gibraltar with the Spanish mainland. This structure, known as Devil's Tower, was demolished during World War II.[26] The German engineer Daniel Specklin is also thought to have been employed in improving Gibraltar's fortifications between 1550–52. Although there is no direct evidence, the Spanish fortifications at the southern end of the town are virtually identical in design to drawings in Specklin's posthumously published Architectura von Vestungen ("The Architecture of Fortresses") and on this basis it has been suggested that he was the designer of Gibraltar's southern works.[25]

Although the 16th century works improved Gibraltar's defences significantly, they still had major shortcomings. Fernandez del Portillo noted in 1610 that while Gibraltar was "girt by quite a good wall with bastions at corners", there still remained work to be done to complete the fortification plans that had been drawn up in the previous century. He felt that "perhaps what does exist is enough to withstand an assault and more."[5] The biggest weakness was the lack of an effective sea wall to resist naval bombardments, and in 1618 Philip III of Spain authorised works to create a new mole for a deep-water harbour, protected by a newly constructed gun platform and the Torre del Tuerto fort.[27] Philip IV subsequently ordered a major modernisation of Gibraltar's fortifications due to hostile activity in the Strait by the Protestant powers of northern Europe – particularly England and the Dutch Republic. On visiting Gibraltar in 1624, the king found that his carriage could not fit through the Landport Gate. He had to walk into the town instead and expressed his displeasure, to which Gibraltar's military governor is said to have retorted: "Sir, the Gate was not made for the passage of carriages, but for the exclusion of enemies."[28]

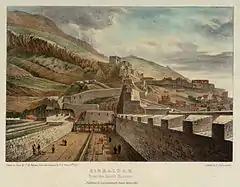

The fortifications had only relatively thin crenelated walls, which were insufficiently strong to counter artillery bombardments. They were lined with many tall towers for archers, but could not be used to mount cannon. Don Luis Bravo de Acuña, the governor of Gibraltar, produced a report for the king recommending a series of changes to the territory's fortifications. A series of new batteries was built along the Line Wall, each named after saints, and a New Mole (later renamed the South Mole) was built to provide additional protection to ships in the harbour.[29] On the north side of Gibraltar, the Muralla de San Bernando (now the Grand Battery) was fully adapted to mount cannon facing the isthmus with the old archery towers being pulled down and replaced by bastions. The Old Mole, stretching into the Bay of Gibraltar, provided further mountings for cannon to sweep the isthmus. A series of defensive works constructed on a glacis above the entrance to the town provided further enfilading fire. A formidable bastion was constructed to protect the south of the town; known as the Baluarte de Nuestra Señora del Rosario ("Bastion of Our Lady of the Rosary"), and now as the South Bastion, it enfiladed the ditch across the Gate of Africa, now the Southport Gates.[30] However, the effectiveness of the new fortifications was undermined by the continued failure of the Spanish crown to provide enough troops to man them.[29]

In August 1704, an Anglo-Dutch invasion force sailed into the Bay of Gibraltar and rapidly overcame the poorly manned garrison. Don Diego de Salinas, the last Spanish governor of Gibraltar, had repeatedly called for the garrison and fortifications to be strengthened, but to no avail. When Admiral George Rooke's fleet carried out the capture of Gibraltar, his 350 guns were opposed by only 80 iron and 32 brass cannon of various calibres in Gibraltar. Most of the Spanish guns were not even manned. De Salinas only had about 150 regular soldiers, very few of whom were gunners, and about 250 armed civilians.[31] Gibraltar fell after only four days of fighting.[32] A Franco-Spanish army laid siege shortly afterwards and was able to inflict substantial damage on the old Spanish fortifications, which crumbled under the constant pounding.[33] However, the Anglo-Dutch garrison was able to repair the worst of the damage and repelled Franco-Spanish attacks while being resupplied and reinforced by sea. After eight months the French and Spanish abandoned the twelfth siege of Gibraltar.[34]

Eighteenth century

The most substantial development of Gibraltar's fortifications took place during the British occupation of the territory from 1704 to the present day. Little was done initially to improve the fortifications, beyond making modest upgrades and repairing the damage caused by the 1704 siege.[35] In 1709, General James Stanhope complained to the Earl of Galway that "the [defence] works in general are in a very bad condition, and the money they have cost I am afraid has been ill laid out", by which he meant that it had been misappropriated.[36] Rather than being spent on the fortifications, the funds had been diverted by corrupt officers to repair their own houses in the town. Other officers were accused of stealing cannons and selling them for profit in Lisbon.[37] Stanhope expressed concern that the prospect of losing Gibraltar was "very practicable" given the poor condition of the defences.[36]

Another siege was mounted in 1727 but the Spanish failed to retake Gibraltar, as the British were once again able to reinforce and resupply the garrison by sea.[35] Following the siege, the Spanish began the construction in 1730 of the Lines of Contravallation, a fortified structure across the entire width of the isthmus anchored by two major forts on each end.[38] This was intended to block access from Gibraltar to the Spanish mainland, and also to serve as a base for any future sieges. The territory's importance increased following Britain's defeat in the Battle of Minorca in 1756, when a French naval victory led to the surrender of the British garrison there.[39]

The first tranche of serious improvements made by the British after the siege focused on the North Front, where the weight of any future attack was likely to be heaviest. A marshy area in front of the Landport Gate was flooded and turned into what became known as "the Inundation", a pear-shaped body of brackish water blocked with palisades, underwater ditches and other hidden obstacles to prevent passage. This left only two narrow approaches to the town, each guarded by barriers and watched over by cannon loaded with lethal grapeshot. The Devil's Tongue Battery was constructed on the Old Mole to provide enfilading fire across the isthmus. The northern defences around the Grand Battery and the Landport were also strengthened.[35]

Further improvements were made under Lord Tyrawley during his term as governor, but progress was hindered by his confrontational relationship with his senior engineer, William Skinner. Gibraltar's defences were stronger than they had been in the earlier siege but still had many deficiencies.[40] The fortress seemed at first sight to be well-armed, with 339 cannon in 1744, but this number concealed the fact that they consisted of at least eight different calibres, some made of brass and some of iron – which meant greatly differing levels of reliability – and they required many different types of spares and ammunition, adding to the garrison's logistical problems.[41]

Skinner and Tyrawley agreed that the most pressing threat was that of a combined land and sea assault focusing on the weakest part of the defences, the open ground between the South Front of the town and Europa Point at the end of the peninsula. However, they disagreed vehemently over where and how to construct the defences. Tyrawley put a great deal of energy into constructing new earthworks, batteries and a series of retrenched lines between the South Bastion and the New Mole, called the Prince of Wales Lines.[40] It was said of him that he would never let a day pass "without visiting the works once or twice during his stay where there was a possibility of going out."[42] Skinner disagreed with the placement of the new fortifications and criticised the use of compacted earth and sun-baked bricks, which had enabled them to be built at great speed and minimum cost, rather than stone. Skinner perhaps had a point, as most of Tyrawley's works were washed away by rain within only a few years.[43]

More fundamental and lasting changes were made under Colonel William Green, who was posted to Gibraltar as its senior engineer in 1761. A veteran soldier with experience of campaigns in the Netherlands and Canada, he arrived in Gibraltar with a wealth of knowledge of the latest methods of fortification.[44] He was strongly supported by Tyrawley's successor as governor, Lieutenant General Edward Cornwallis, who wrote in 1768:

Gibraltar has its faults, but, with them, as tenable in my opinion as any place in Europe : where it is vulnerable is the sea . . . though it has often been said that Gibraltar is impregnable, which no place is according to my notions, it was always understood "while you commend the sea". The bay is extensive, our garrison small . . ."[45]

Funds were scarce in the 1760s but a number of improvements were made to the North Front defences and the sea wall from South Bastion to Europa Point, which was severely damaged by a great storm in 1766. Green spent several years reviewing the state of the fortifications and developing a plan to improve them. He sent a report to the Board of Ordnance in London in 1762 and another in 1768.[46] The following year he travelled to London to present his conclusions to a commission appointed by William Pitt the Elder.[45] He summed up his three principal aims as being to prevent a possible landing by sea; to improve the quality of the garrison and its provisioning; and to keep the enemy at a distance with artillery.[47]

After a lengthy debate the government approved his plans and Green returned to Gibraltar to implement them. The territory's fortifications were still largely based around the old Spanish and Moorish defences, though these had been strengthened and supplemented over the years.[46] The sea wall was still much as it had been in the Spanish period and still represented a weak point, and a lack of accommodation for the 4,000 officers and men of the garrison was also a major problem. Green set about thoroughly overhauling, redesigning and re-siting the fortifications, building new bastions, redans, storehouses, hospitals, magazines and bomb-proof barracks and casemates.[47] Among his most important improvements was the construction of the King's Bastion, a fortification projecting from the sea wall between the Old and New Moles. It mounted twelve 32-pounder guns and ten 8-inch howitzers on its front, with another ten guns and howitzers on its flanks, allowing heavy fire to be directed out into the bay and enfilading the sea wall in both directions. Its massive structure, with solid stone parapets up to 15 feet (4.6 m) thick, could house 800 men in its casemates.[48]

To carry out the improvements more efficiently and cheaply, Green raised a Soldier Artificer Company – a predecessor of the Royal Engineers – of skilled labourers under military discipline.[45] He also improved the garrison's state of preparation for a fresh siege. The quality of the guns was improved; by 1776 there were 98 pointing north plus two mortars and two howitzers. Another 300 were mounted on the Line Wall and the south front, and there was room for a further 106. The guns were kept constantly loaded with several rounds positioned nearby in reserve, in case of a surprise attack.[49] The Spanish historian López de Ayala remarked on how well prepared the garrison was:

One of the most noteworthy things about this place is that there is no cannon, there is no mortar or howitzer without its known and predetermined target . . . twice a day, at sunrise and sunset, the battery commander himself inspects the guns. He checks whether the wick is alight, the gun loaded, primed, and trained on its allotted target."[49]

Green's improvements came just in time to meet the challenge of the Great Siege of Gibraltar between 1779–83. Despite the siege, the defences were continually improved under Green's supervision. More batteries and bastions were constructed on the North Front, all the way up to the summit of the Rock.[50] The first of Gibraltar's many tunnels was also constructed, with the original intention of reaching a rocky outcrop called the Notch on the north face of the Rock, to cover a blind angle on the Mediterranean side. As the tunnel was being constructed, an air vent was excavated using explosives. The tunnellers realised that they could use the shaft as an embrasure for a gun. They turned the tunnel into the first of a series of galleries with embrasures at intervals, overlooking the isthmus, which could be used to bombard the enemy lines with impunity.[51] The tunnelling continued after the siege and by 1790 over 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of tunnels had been excavated, providing bombproof communications routes between the various lines and batteries on the North Front of the Rock. The Notch was also reached and was hollowed out to become a large gallery, called St George's Hall, capable of accommodating five guns.[52]

Further works were carried out to repair, rebuild and improve the defences around the Waterport Front, which incorporated the old Waterport Gate. New casemates, counterguards, tenailles and lunettes were built in the area and the Montagu and Orange Bastions were enlarged. The work was carried out amidst considerable controversy, as there were vigorous disagreements between the governors and senior engineers of the time over how the works should be carried out and indeed whether some of them should be pursued at all.[53]

Nineteenth century

Gibraltar remained at peace for 121 years after the Great Siege – one of the longest periods of peace in its history – but work continued to develop the fortifications, driven to a large extent by the increasingly rapid pace of change in the power and range of artillery. The Grand Casemates, a huge bombproof barracks, was built in 1817.[54] Proposals were put forward in 1826 to rebuild the Line Wall with new bastions, though they were never put into practice. In 1841, General Sir John Thomas Jones of the Royal Engineers conducted a study of Gibraltar's defences which prompted major changes and defined the nature of the fortifications for many years to come.[55]

Jones's recommendations were based on a number of key assumptions about the threats faced in particular sectors of the fortifications. First, the North Front was so strongly defended that it was very unlikely to be vulnerable. Second, the sea defences below the South Bastion could be breached but an invader would still face the barrier of the South Front. Third, the Europa defences might also be breached, but a defender holding the narrow Europa Pass or the heights of Windmill Hill could easily enfilade an invader; as Jones put it, "two hundred men on Windmill Hill and Europa Pass ought to hold as many thousands at bay". Fourth, the main threat was – as Green had recognised 80 years earlier – to the town itself. An enemy breaching the sea wall in the town would bypass the two land fronts and be able to attack them from their highly vulnerable rear.[56]

Jones also recognised that the development of more powerful and accurate artillery made the old system of shoreline batteries extremely vulnerable. He proposed that the shoreline artillery should be pulled back some 300 yards (270 metres) to "retired batteries" situated higher up the hill, equipped with the latest and most powerful guns and firing from barbettes rather than through embrasures. Such positions could not easily be seen from the sea, were out of the effective range of enemy ships and could not be flanked by landward guns. The sea wall would be defended solely by musket fire with the artillery support being provided from the bastions and retired batteries.[57]

Jones's recommendations were immediately accepted and put into practice. A series of new batteries aligned on a roughly north-south axis facing west towards the harbour was constructed, including Jones', Civil Hospital, Raglan's, Gardiner's, Queen Victoria's, Lady Augusta's, Prince of Wales and Cumberland batteries. Further batteries and fortifications were constructed around Rosia Bay near the south of the peninsula and Windmill Hill was strengthened around its entire perimeter, with Retrenched Barracks at its north end blocking access to the higher ground behind. The sea wall in the town was straightened and strengthened with the building of two new curtain walls, Prince Albert's Front and Wellington Front. Defensive breakwaters were constructed in front of both to prevent an armoured enemy ship ramming the walls.[1]

Gibraltar's guns were reorganised and upgraded from 1856. Many of the 24-pounder guns were replaced with 32-pounders and the retired batteries were equipped with 68-pounders. A wide variety of old guns was still in use, including iron-cast 6-, 12- and 18-pounder, which complicated the supply and maintenance of the batteries. At its peak, the fortress had 681 guns in 110 batteries and positions. As the British artist William Henry Bartlett put it in 1851, "Ranges of batteries rising from the sea, tier above tier, extend along its entire sea-front, at the northern extremity of which is the town ; every nook in the crags bristles with artillery".[58] However, only a decade later the rapid introduction of rifled artillery firing explosive shells was already beginning to make the fortifications obsolete. As a result of recommendations by Colonel William Jervois, the coastal batteries were upgraded with armoured casemates made from expensively constructed iron laminates. He also proposed to build a sea fort in the bay, along the lines of Britain's Palmerston Forts, though this was never carried out.[59]

In 1879 the growing threat of ultra-heavy naval artillery led to the installation of two giant RML 17.72 inch guns, dubbed the "100 ton guns" – the biggest, heaviest and among the last muzzle-loading artillery pieces ever made. They were never used in anger and were not particularly reliable, suffering from a rate of fire of only one shot every four minutes.[60] They were soon replaced by more reliable and powerful breech-loading guns and the process of pulling back the guns to retired sites continued until it reached its logical end point of situating the principal batteries on the very peak of the Rock, 1,400 feet (430 metres) above sea level. At this height, weather and communications became serious problems. Gibraltar is prone to a weather formation called the Levanter cloud, which often obscures the top of the Rock. Telegraphic cables were installed criss-crossing the Rock to allow the batteries to communicate with observation posts situated lower down. The observers would plot the movement of enemy targets and transmit the coordinates to the batteries high above.[61]

The conversion of Gibraltar's armament to breech-loading guns led to a further reappraisal of the fortress's defensive needs in 1888. A report by Generals William Howley Goodenough and Sir Lothian Nicholson, the governor at the time, recommended reducing and standardising the guns to make them easier to maintain and supply. Six-inch (150 mm) quick-firing guns and machine guns were introduced in the coastal positions and 9.2-inch guns were installed in the retired batteries. The smaller guns would be sufficient to protect against fast-moving enemy vessels, such as torpedo boats, while the larger guns could cover the entire Strait as far as the North African shore and could fire right over the Rock to counter-bombard land-based artillery. Fourteen 9.2-inch guns were eventually installed, along with another fourteen 6-inch guns, to provide Gibraltar's primary artillery defences.[62] Another four 4-inch and ten 12-pounder guns were installed in various strategic positions, mostly along the coastline, to provide inshore defence.[63]

Twentieth century

By the start of the 20th century it was clear that Gibraltar could be bombarded with relative impunity from the Spanish mainland. Proposals were put forward to build a new harbour on the east side of the Rock, where ships would be less vulnerable to direct artillery fire from the mainland, but were abandoned due to the vast expense and only marginal gains in security.[64] A new round of tunnelling was carried out to provide more bombproof accommodation for the garrison, along with deep shelters and casemates capable of accommodating 2,000 men. Ultimately it was decided in 1906 that Gibraltar faced no credible threat from land and that the defences would be organised to deal with a threat from the sea.[65]

In the event, the biggest threat Gibraltar faced in the 20th century came from the air. The only action seen by Gibraltar's coastal defences during the First World War occurred in August 1917 when the 6-inch gun at Devil's Gap Battery engaged and sank a German U-boat travelling on the surface. The Second World War presented a much greater challenge to Gibraltar's defences as a result of the development of long-range bomber aircraft.[66] Numerous anti-aircraft positions were established across Gibraltar, many of them built on top of existing fortifications and equipped with 40 mm and 3.7-inch anti-aircraft guns.[67] By March 1941 there were twenty-eight 3.7-inch guns and twenty-two (and eventually forty-eight) Bofors guns, plus two pom-pom guns. Numerous searchlights were installed – by 1942 there were twenty-four located around Gibraltar – and rocket projectors, an early though rather ineffectual form of anti-aircraft missiles, were also brought in.[68] Bunkers and pillboxes were built to guard against amphibious landings, especially on the eastern side of the Rock,[67] and anti-tank guns, ditches and obstacles were installed facing the isthmus to guard against a land attack.[69]

The possibility of an attack from the land was not a theoretical concern, as Adolf Hitler sought Spanish support to carry out Operation Felix, an invasion of Gibraltar that would have enabled the Germans to close the entrance to the Mediterranean to the great disadvantage of the Allies. It was projected that Gibraltar would fall within only three days.[70] In the event, Hitler failed to reach an agreement with the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco.[71] Gibraltar's defences were tested several times by air raids carried out by Italy and Vichy France, which only caused limited damage and light casualties,[68] and by Italian submarine and sabotage attacks which damaged or sank a number of ships in the bay.[72]

Despite the pinprick nature of the Axis attacks, a huge amount of work was done during the war to develop Gibraltar's fortifications further. A new network of tunnels was dug under the Rock to accommodate a vastly increased garrison. The tunnels became what amounted to an underground city, secure from bombardment and capable of sheltering 16,000 men. They included a hospital, storerooms, workshops, ammunition magazines, a bakery, food stores capable of holding enough rations to feed the entire garrison for sixteen months, a power station, a water distillation plant and a telephone exchange.[73] Much of the spoil was used to build a runway across the isthmus and extending into the bay, with an eventual length of 1,800 yards (1,600 metres) and a width of 150 yards (140 metres).[74] The Royal Air Force base on Gibraltar supported Allied air operations in the Battle of the Atlantic, the Mediterranean and North Africa. During Operation Torch in 1942, over 600 Allied aircraft were crammed onto Gibraltar's single runway.[75]

Following the Second World War, changes in Britain's military commitments and the strategic environment eventually made Gibraltar's role as a fortress superfluous. The Royal Navy's historic role in the Mediterranean was effectively taken over by the United States Sixth Fleet and Britain's strategic interests shifted to the Atlantic.[73] Some further work took place between 1958–68 when Gibraltar was used as a NATO monitoring station to observe naval traffic through the Strait.[76] Linking tunnels were dug to connect the existing tunnels, new storage chambers and reservoirs were built and access routes to permit easier movement between areas of the peninsula were constructed. The tunnelling work came to an end in April 1968, marking the end of the British Army's 200 years of tunnel-building.[77] The 9.2 inch guns mounted on the Upper Ridge of the Rock remained in service until 7 April 1976 when the guns of Lord Airey's, O'Hara's and Spur Batteries were all fired for the last time.[78] In October 1985, a single battery of Exocet anti-ship missiles was installed on the Rock;[79] they were a specially adapted version of the MM38 ship borne missile known as "Excalibur" and were directed by a Type 1006 radar. The system had reportedly been withdrawn by 1997.[80] During the 1980s and 1990s, the British Ministry of Defence closed Gibraltar's naval dockyard and greatly reduced the military presence in the territory, leaving the locally raised Royal Gibraltar Regiment as the main military force in Gibraltar.[76]

Gibraltar's fortifications today

Landport Front defences as seen from the North Bastion in 1828

Landport Front defences as seen from the North Bastion in 1828 The same view in 2013, looking towards the Moorish Castle

The same view in 2013, looking towards the Moorish Castle

Many of Gibraltar's fortifications were already redundant well before the British garrison was withdrawn from the territory in the 1990s, and the rapid military rundown in the 1980s and the 1990s left the civilian authorities with a large amount of surplus military property. Many of the best-preserved fortifications are in the Upper Rock Nature Reserve, a conservation area that covers about 40% of the area of Gibraltar. A few of the Upper Rock batteries have been preserved intact; all four of the 5.25-inch guns at Princess Anne's Battery are still in place, making it the only place in the world where a complete 5.25-inch battery can still be seen.[81] The 9.2 inch guns at Breakneck, Lord Airey's and O'Hara's Batteries are still in situ and can now be visited. Elsewhere, most of the ordnance has been removed. Two surviving 6-inch guns remain at Devil's Gap Battery, one of which is the gun that engaged a German U-boat in August 1917.[82] At Napier of Magdala Battery one of the two 100-ton RML 17.72 inch guns is still in situ and has been restored, along with a 3.7 inch quick-firing anti-aircraft gun. The site is now run by the Gibraltar Tourist Board in conjunction with the Nature Reserve.[83]

Some of the 18th and 20th century tunnels can also be visited. The Upper Galleries (now known as the Great Siege Tunnels) on the North Face of the Rock of Gibraltar are a popular tourist attraction within the Nature Reserve. A number of tableaux have been installed to recreate the appearance of the original 18th century gun batteries housed within the tunnels.[84] They include a number of Victorian 64-pounder cannon on original Gibraltar gun carriages.[85] The Middle Galleries, where World War II tunnelling joins the original 18th century tunnels, are open under the name of the "World War II Tunnels".[86] The Lower Galleries are not open to visitors, as they are in a poor condition due to vandalism and neglect, but still contain many relics of their former military usage.[87]

The Tower of Homage, part of Gibraltar's Moorish Castle

The Tower of Homage, part of Gibraltar's Moorish Castle The Southport Gates, bearing Charles V's arms

The Southport Gates, bearing Charles V's arms

Many of the fortifications at sea level have survived, though not always in their original condition. A substantial number have been built over. The Inundation was drained after World War II and is now the site of the Laguna Estate, named after the Inundation's lagoon. The glacis was likewise used as the foundations of the Glacis Estate.[85] The flat ground of the retired batteries made them prime building spots during Gibraltar's post-war building boom, thus many of them have disappeared under recent developments. The city walls have almost entirely survived and are progressively being cleared of modern structures to restore them to something more like their original appearance. However, they are no longer at the water's edge due to extensive land reclamation.[88] Various parts of the fortifications have been converted to civilian use. After being used for some years as a hostel for Moroccan migrant workers, the Grand Casemates Barracks have been renovated and converted into restaurants and shops.[85] An electricity generating station was built inside the King's Bastion in the 1960s but has since been demolished and the bastion has been converted into a leisure centre.[88]

The North Front defences, still following the course laid out by the Moors in the 11th century, are still substantially intact. A significant portion of the original Spanish and Moorish walls can still be seen, rising in a saw-tooth (en crémaillère) fashion from the Grand Battery.[82] Although gaps have been cut in the walls to allow vehicle traffic to enter the city centre, pedestrians can still walk over the wooden drawbridge over the North Front ditch to pass through the Landport Gate into the city.[88] The Moorish Tower of Homage continues to stand above the Grand Battery on the lower slopes of the Rock. It is now open to the public as part of the Upper Rock Nature Reserve.[89]

The walls of the South Front are also substantially intact. The Southport Gates still bear the arms of Charles V, with columns on either side representing the Pillars of Hercules entwined with scrolls reading "plus ultra", the national motto of Spain. Flanking the base of the royal arms are the arms of Gibraltar and of one of the Spanish governors.[90] The ditch that once adjoined the gates has largely been filled in, though a portion of it was reused to create the Trafalgar Cemetery adjoining the Southport Gates. Further south, the upper section of Charles V Wall is intact and can be walked on; the lowest point of this section, Prince Ferdinand's Battery, is now the site of the Apes' Den, where many of Gibraltar's colony of Barbary macaques live.[83] Many of the clifftop defences and gun emplacements in the far south of the peninsula are still visible, though some have been built on and others have been turned into viewing platforms.[82]

Conserving the fortifications

Abandoned and vandalised, the Bombproof Barracks on the Prince's Lines

Abandoned and vandalised, the Bombproof Barracks on the Prince's Lines.JPG.webp) The rusting remains of a World War II searchlight on the Northern Defences

The rusting remains of a World War II searchlight on the Northern Defences

The preservation of Gibraltar's fortifications, and of its architectural heritage in general, has been a problematic issue. The peninsula is extremely short of land; in the early 1980s, nearly half the available land was in military usage, comprising the naval dockyard, the whole of the southern part of Gibraltar, the upper part of the Rock and a significant amount of property within the city walls, in addition to the runway and military facilities on the isthmus. Until recently, Gibraltar had no public sea front of its own due to military land usage.[91] As the military presence has been run down, MOD property has been handed over to the Government of Gibraltar but the latter has lacked the resources to look after all of the buildings and land that have been transferred. This has led to the abandonment and severe physical deterioration of significant parts of Gibraltar's military heritage.[92]

A prime example is that of the Northern Defences, consisting of the King's Lines, Queen's Lines and Prince's Lines overlooking the isthmus and the entrance to Gibraltar. Mostly dating during the Great Siege and shortly after, they have been described as "not merely one of the most, perhaps the most, hauntingly vivid experiences of a visit to Gibraltar . . . [standing] comparison with some of the most famous military sites in the world."[93] As John Harris of the Royal Institute of British Architects has put it, they are "capable of providing one of the great architectural experiences in the western world . . . the atmosphere of the Great Siege is vivid and evocative in the extreme."[94] The Gibraltar Conservation Society proposed a £500,000 scheme in the early 1980s to preserve and reopen the Lines and the surrounding batteries, galleries and bombproof magazines,[93] but the scheme did not go ahead and the Lines have continued to be neglected and vandalised despite being scheduled as an Ancient Monument.[95]

References

- Hughes & Migos, p. 91

- Rose (2001), p. 95

- Fa and Finlayson, pp. 4–5

- Rose (1998), p. 92

- Hills, p. 121

- Wright, p. 25

- Jackson, pp. 31–32

- Hills, p. 13

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 11

- Jackson, pp. 34–35

- Hills, p. 39

- Hills, p. 49

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 9

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 12

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 16

- "The Islamic City and Fortifications". Moorish Castle, Gibraltar

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 14

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 56

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 13

- Hills, p. 86

- Jackson, p. 57

- Jackson, p. 73

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 17

- Hills, p. 106

- Hughes & Migos, p. 31

- Jackson, p. 75

- Hills, p. 124

- Jackson, p. 82

- Jackson, p. 84

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 20

- Jackson, p. 96

- Jackson, p. 99

- Jackson, p. 108-9

- Jackson, p. 110-11

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 25

- Hills, p. 216

- Hughes & Migos, p. 36

- Hughes & Migos, p. 364

- Jackson, p. 144

- Hughes & Migos, p. 40

- Hughes & Migos, p. 38

- Hughes & Migos, p. 42

- Hughes & Migos, p. 41

- Jackson, p. 147

- Hills, p. 308

- Hughes & Migos, p. 43

- Hughes & Migos, p. 48

- Hughes & Migos, p. 280

- Hills, p. 309

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 29

- Hughes & Migos, p. 59

- Hughes & Migos, p. 72–3

- Hughes & Migos, pp. 76–82

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 31

- Hughes & Migos, pp. 88–89

- Hughes & Migos, pp. 89–90

- Hughes & Migos, p. 90

- Bartlett, p. 128

- Hughes & Migos, p. 92–3

- Hughes & Migos, p. 125

- Hughes & Migos, p. 128

- Hughes & Migos, p. 130

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 36

- Jackson, p. 258

- Hughes & Migos, p. 134

- Hughes & Migos, p. 141

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 45

- Hughes & Migos, p. 151

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 46

- Jackson, p. 282

- Jackson, p. 283

- Hughes & Migos, p. 150

- Hughes & Migos, p. 153

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 47

- Rose (2001), p. 107

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 53

- Rose (2001), p. 112

- Hughes & Migos, p. 365

- Exocet Deployed, The Montreal Gazette, October 25, 1985 (p. 15)

- Friedman, Norman (1997), The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapons Systems, 1997–1998, The US Naval Institute, Annapolis, Maryland, ISBN 1-55750-268-4 (p.227)

- "Discover Gibraltar – Princess Anne's Battery". Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 58

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 57

- "Discover Gibraltar – Great Siege Tunnels". Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 54

- "Discover Gibraltar – WW2 Tunnels". Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- "Discover Gibraltar – Star Chamber". Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 55

- Fa and Finlayson, pp. 55–6

- Fa and Finlayson, p. 22

- Binney & Martin, p. 11

- Binney & Martin, p. 13

- Binney & Martin, p. 18

- Harris, p. 7

- Allan, p. 9

Bibliography

- Allan, George (1982). "Safeguards for Gibraltar's Heritage". Save Gibraltar's Heritage. London: Save Britain's Heritage. ISBN 0-905978-13-7.

- Bartlett, William Henry (1851). Gleanings, Pictorial and Antiquarian, on the Overland Route. London: Hall, Virtue & Co. OCLC 27113570.

- Binney, Marcus; Martin, Kit (1982). "Tourism, Conservation and Development". Save Gibraltar's Heritage. London: Save Britain's Heritage. ISBN 0-905978-13-7.

- Fa, Darren; Finlayson, Clive (2006). The Fortifications of Gibraltar. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-016-1.

- Harris, John (1982). "An Architectural Appreciation". Save Gibraltar's Heritage. London: Save Britain's Heritage. ISBN 0-905978-13-7.

- Hills, George (1974). Rock of Contention: A history of Gibraltar. London: Robert Hale & Company. ISBN 0-7091-4352-4.

- Hughes, Quentin; Migos, Athanassios (1995). Strong as the Rock of Gibraltar. Gibraltar: Exchange Publications. OCLC 48491998.

- Jackson, William G. F. (1986). The Rock of the Gibraltarians. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3237-8.

- Rose, Edward P.F. (1998). "Environmental geology of Gibraltar: living with limited resources". In Bennett, Matthew R.; Doyle, Peter (eds.). Issues in environmental geology: a British perspective. London: Geological Society. pp. 95–121. ISBN 978-1-86239-014-0.

- Rose, Edward P.F. (2001). "Military Engineering on the Rock of Gibraltar and its Geoenvironmental Legacy". In Ehlen, Judy; Harmon, Russell S. (eds.). The Environmental Legacy of Military Operations. Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America. ISBN 0-8137-4114-9.

- Wright, George Newenham (1840). The shores and islands of the Mediterranean, drawn by sir G. Temple, bart. London: Fisher, Son & Co.

.svg.png.webp)