Francis Reynolds-Moreton, 3rd Baron Ducie

Francis Reynolds-Moreton, 3rd Baron Ducie (28 March 1739 – 20 August 1808)[1] was a British Royal Navy officer, peer and politician who participated in numerous engagements during the American War of Independence. He is largely noted for his role conflict at the Battle of Red Bank in 1777 during the Philadelphia campaign, involving the dual siege of Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer. During this operation he was commander of the advance fleet on board HMS Augusta in an attempt to clear the way along the Delaware to Philadelphia. His ship ran aground while being pursued by Commodore Hazelwood's fleet when the vessel mysteriously caught fire shortly thereafter and exploded before all of the crew could abandon ship.[2][3][4] Reynolds also commanded HMS Jupiter and HMS Monarch in several operations and saw service against the French in the North Sea, European Atlantic coast and the Caribbean theaters.[5]

The Lord Ducie | |

|---|---|

Portrait by George Romney | |

| Born | Francis Reynolds 28 March 1739 |

| Died | 20 August 1808 (aged 69) |

Early life

Little is known about the childhood and education of Francis Reynolds. The Ducie family was descended from a family in Normandy.[6] Francis was the son of Francis Reynold and Elizabeth Moreton. He was born at Strangeways, Manchester,[5] and baptized 25 June 1739, at Manchester Cathedral.[5] He assumed the title of Esquire in 1757. He married twice. Firstly in 1774 to Mary Purvis of Shepton Mallet, by whom he had two sons: his heir Thomas, and Augustus John, who became a Lieutenant colonel in the 1st Foot Guards. After Mary's death, he remarried in 1791 to Sarah Child, widow of the London banker Robert Child.[7][8] His brother, Thomas Reynolds, was the second Baron Ducie of Tortworth. Francis Reynolds assumed the last name of Moreton in 1786.[1][7]

Military service

After becoming a midshipman Reynolds passed the Lieutenant's Examination on 27 April 1758, assumed the rank of Lieutenant on 28 April 1758, at the age of 19 and achieved the rank of Commander on 21 November 1760.[9] His first known service was in April 1752. Serving in the Seven Years' War Reynolds took command of HMS Weazel; Provost Marshal of Barbadoes, 16 March 1761 – 1808; Post Captain, 12 April 1762; M.P., Lancaster, 1784–1785.[9][1]

Reynolds was appointed captain of HMS Ludlow Castle, bearing 44 guns, on 12 April 1762, commanding to 25 May 1762,which was undergoing repairs at Deptford where he joined the small frigate HMS Garland, bearing 24 guns, on 24 May. At the end of that month she sailed for Plymouth, and was assigned to duty off the coast of France and later in a voyage to Africa prior to being paid off at Chatham in February 1763.[5]

American Revolutionary War

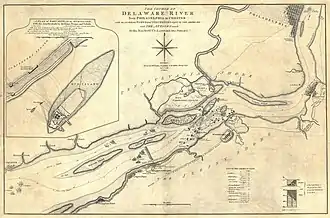

Reynolds was the commander aboard HMS Augusta, a ship of the line bearing 64 guns, which was part of the advance British fleet[lower-alpha 1] in the effort to reach Philadelphia during the American Revolutionary War. John Hazelwood, Commodore of the Pennsylvania Navy and Continental Navy, planned for the defence of the Delaware River approach to Philadelphia during the Siege of Fort Mifflin, which lasted approximately three weeks.[11]

On 12 October 1777, General Howe[lower-alpha 2] issued orders to capture the two newly constructed American forts, Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer, which were preventing a British naval attempt to resupply British troops occupying Philadelphia by way of the Delaware River. The British shore batteries established on the Pennsylvania side of the river opened fire on Fort Mifflin, while Colonel Carl von Donop, in command of some 2000 Hessian mercenary soldiers landed on the New Jersey shore and attacked Fort Mercer. At this time the British fleets were advancing up river to lend support to von Donop by bombarding both Forts Mercer and Mifflin. As von Donop's men assaulted Fort Mercer, Reynolds' advanced Delaware River squadron proceeded up river via the eastern or main channel with the intention of bombarding Fort Mifflin. At the same time Reynolds' fleet were to engage the American galleys harboring off Red Bank in order to draw them away from supporting the Hessian attack on Fort Mercer, however, there was no way for Reynolds' fleet and von Donop's land forces to communicate and coordinate their efforts, which proved ineffectual.[12][13][lower-alpha 3]

Hazelwood's fleet immediately engaged Reynolds' fleet, forcing him to withdraw down river. With the river tidewater now receding, Reynolds' ship, along with HMS Merlin grounded and stuck fast in a sand bar during an effort to go around the obstacles placed in the river, leaving the Augusta tilted at its starboard side. While being engaged by Hazelwood's fleet Reynolds had the crew remove stores of supplies in an effort to lighten its load and free the vessel, but the attempt was futile as more time was needed[15] as a fire broke out below deck and quickly spread, forcing Reynolds and his crew to abandon ship. Shortly thereafter, just past noon, before all of the crew could escape, the fire reached the powder magazine and the Augusta exploded, killing some of the crew members.[16][17][lower-alpha 4] The Augusta blew up with such great force it was heard 30 miles (48 km) away in Trappe, Pennsylvania.[18][3][lower-alpha 5] Before leaving the scene, Reynolds had the Merlin set fire to prevent its capture by the Americans. The loss of the Augusta was unexpected and unsettling to the British commanders. After destroying the Merlin Reynolds retreated to the New Jersey shore to a road just south of Billingsport.[19]

Accounts of the explosion vary between the belligerents and among the commanding officer and crew. During their testimony at the inquiry Reynolds or none of the crew could say what actually caused the fire. No one could recall anything that would cause such a fire to break out on the decks or below. Only Midshipman Reid speculated that the fire originated from the cannon wads. Admiral Howe seemed to accept this explanation as very likely when he entered in his diary, "…by some Accident, no other way connected with the circumstances of the action but as it was probably caused by the Wads from her guns, the ship took fire abaft…"[12][20] Naval historian James Fennimore Cooper, in his History of the Navy of the United States, maintains that the Augusta had her stores of supplies lightened before embarking on her mission and that the fire originated in some pressed hay which had been packed into the hull to render the vessel more resistant to shot. American accounts generally maintain that it was the American fire rafts that caused the fire.[18][20][21][22]

- Aftermath

Record of any preparation for coordination of the land attack with naval support between Reynolds and von Donop are inconclusive. There was no possible way for the two distant commanders to communicate with each other during the siege. From the beginning it seemed that Reynolds had no way of knowing at what time von Donop would commence his assault. As nightfall approached it would have been reasonable for Reynolds to assume that von Donop's attack might not begin until the next morning.[18]

At his court-martial a month later, on 26 November, presided over by Captain George Ourry aboard HMS Somerset off Billingsport, Captain Reynolds testified, "…I thought it my duty to comply with Admiral Richard Howe's instructions in giving every Assistance to the Hessians: I immediately hoisted the Topsails and sent an Officer to each of the other ships acquainting the Captains that my intention was to go as near the upper Cheveaux de frize as possible, in order to draw the fire of the Galleys from the Hessians, and I desired they would do the same, which they complied with…" Reynolds was acquitted of all charges attributable to the loss of Augusta. Shortly thereafter Reynolds returned to England aboard the transport Dutton,[lower-alpha 6] entrusted with dispatches from Vice-Admiral Lord Howe.[5] Given the delayed activity of the ships' progress trying to bypass the river obstacles by Billingsport, the order to proceed up river, when it finally came, while anticipated, still caught the squadron somewhat unprepared.[12]

Other service

Reynolds' next command was over HMS Jupiter, bearing 50 guns, to which he was appointed in July 1778, shortly after her keel laying and completion. Jupiter departed from Portsmouth on 28 August to sail for Elsinore with the Saint Petersburg convoy. On 20 October, cruising off Cape Finisterre, sailing with the frigate HMS Medea, commanded by Captain James Montagu, Reynolds took to chase after the French Triton, a ship of the line bearing 64 guns, commanded by the Comte de Ligondés, initially thinking that she was an East Indiaman before ascertaining her real identity. After a five-hour afternoon chase a ferocious battle commenced in stormy weather at about 6 p.m. Within thirty minutes the Medea, engaging the Triton on her lee quarter while the Jupiter attacked from her windward side, was forced out of the action. Thereafter the difficulty of fighting in the darkness near the shore prevented Reynolds from concluding what he assumed would be a likely victory. During the two-hour engagement the Triton suffered casualties of thirteen men killed and thirty wounded, including her commander who had been obliged to leave the deck, while the Jupiter's casualties included three men killed and eleven wounded. The Triton put into A Coruña to make repairs while the two British vessels made for Lisbon to attend to their own repairs.[5][9]

On 20 September 1780, Reynolds assumed command of HMS Monarch, a ship of the line bearing 74 guns and sailed with Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood's reinforcements headed for the West Indies in late October. He was present at the Capture of Saint Eustatius on 3 February 1781, and was chosen by Admiral George Rodney to depart with the Monarch, HMS Panther and HMS Sybil, and pursue the Dutch frigate Mars.[23] On 4 February Reynolds engaged Mars, forcing her to strike her colours and surrender. During the action the senior officer, Rear-Admiral Willem Krull, was killed. On 29 April, serving under Admiral Hood, Reynolds, still in command of Monarch, was present at the Battle of Fort Royal.[5]

As commander of HMS Monarch, part of the fleet under commander Thomas Graves, Reynolds fought at the Battle of the Chesapeake in 1781.[24] On 26 January 1782, Reynolds, commander of HMS Monarch, was present at the Battle of Saint Kitts.[9] On 12 April 1782, still in command of the Monarch, serving under Admiral Sir George Rodney, Reynolds participated at the Battle of the Saintes.[25][26]

On 1 April 1779, Reynolds departed Portsmouth with Jupiter and within a few hours came upon and assisted the British sloop HMS Delight, bearing 14 guns, commanded by Admiral John Leigh Douglas, while he was in the process of capturing the French privateer Jean Bart. Reynolds took custody of the prize and carried her into Plymouth so that the sloop could proceed on her Admiralty orders, and he then left the Devonshire port on 4 April to sail in the Bay of Biscay and observe the activities of the French fleet.[5][27]

Reynolds was commissioned captain of a company in the Gloucestershire Regiment of Volunteers, on 22 August 1803.[1][28]

Later life

On 9 September 1785, Reynolds was elected a Member of Parliament for Lancaster, Lancashire.[12] On 11 September 1785, he succeeded his elder brother as Baron Ducie.[9] Sometime thereafter he became Clerk of the Crown in County Palatine of Lancaster.[1]

Ducie Island, in the Pacific Ocean, was named after him by Captain Edward Edwards of HMS Pandora, who had served under Ducie during his time in command of HMS Augusta.[29]

See also

- Tadeusz Kościuszko, designer and engineer of Fort Mercer

- Fort Billingsport, Revolutionary War era fort on the Delaware River

- List of American Revolutionary War battles

- List of nautical terms

Notes

- Other ships of Reynolds' advance fleet included HMS Roebuck, with forty-four guns, commanded by Captain A. S. Hamond; HMS Liverpool, twenty-eight guns, Captain Henry Bellew; HMS Pearl, thirty-two guns, Captain Thomas Wilkinson; and HMS Merlin, a sloop-of-war, sixteen guns, Commander Samuel Reeve.[10]

- Not to be confused with his older brother Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe

- Later into the assault on Fort Mercer von Donop was mortally wounded while some 400 of his soldiers were killed or wounded; The Americans suffered about 40 casualties.[14]

- The exact number of casualties is not known. The Augusta was the largest British vessel lost in combat by the Royal Navy in either the Revolutionary War or in the War of 1812.[3]

- During this time Thomas Paine was traveling between Germantown and Whitemarsh with General Nathanael Greene's division and could hear the exchange of cannon fire in the battle. In a letter to Benjamin Franklin he exclaimed that he had heard, "A cannonade, by far the most furious I ever heard". Of the explosion he wrote, "...we were stunned with a report as loud as a peal of a hundred cannon at once, and turning round I saw a thick smoke rising like a pillar and spreading from the top like a tree…".[12]

- Not to be confused with HMS Dutton

Citations

- Doyle, 1886, pp. 640–642

- Leach, 1902, p. 4

- Miller, 2000, p. 46

- Cooper, 1848, pp. 149–151

- Hiscocks, 2018, Essay

- Clarke, Jones & Jones, 1799, p. 3

- Cokayne, 1916, Vol III, pp. 474–475

- Burke, 1832, p.361

- Harrison, 2010, Three Decks, Biographical outline

- McGeorge, 1905, p. 5

- Leach, 1902, p. 2

- Friends of Red Bank Battlefield, 2017, Essay

- McGeorge, 1905, pp. 3–7

- Chartrand, 2016, pp. 27-28

- Dorwart 1998, pp. 40–41

- Wallace, 1884, p. 187

- Sparks, 1853, p. 12

- McGuire, 2007, pp. 174–175

- Dorwart 1998, pp. 40-41

- McGeorge, 1905, p. 9

- Martin, 1993, pp. 136-137

- Cooper, 1848, p. 150

- Mundy, 1830, p. 11

- The London Gazette, 15 April 1801, issue 15354, pp. 401–404

- Fraser, 1904, pp. 76-77

- Cokayne, 1916, p. 475

- "No. 11967". The London Gazette. 3 April 1779. p. 1.

- "No. 15623". The London Gazette. 24 September 1803. p. 1298.

- Heffernan, Thomas Farel (1990). Stove by a Whale: Owen Chase and the Essex. Wesleyan University Press. p. 80. ISBN 0-8195-6244-0.

Bibliography

- Burke, John (1832). A General and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley. p. 361.

- Chartrand, René (2016). Forts of the American Revolution 1775–83. Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4728-1445-6.

- Clarke, James Stanier; Jones, Stephen; John, Jones, eds. (1799). The Naval Chronicle. Vol. III. London: J. Gold.

- Cokayne, George Edward (1916). Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct, Or Dormant. Vol. III. The Saint Catherine Press. pp. 475–476.

Note: This second publication differs from the G. Bell & sons publication of 1890 where the Reynolds account is found in volume three on p. 178, and covered in fewer words.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - Cooper, James Fenimore (1848). History of the Navy of the United States of America. Cooperstown: Published by H. & E. Phinney.

- Dorwart, Jeffery M. (1998). Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia: An Illustrated History. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1644-8.

- Doyle, James William Edmund (1886). The Official Baronage of England: Showing the Succession, Dignities, and Offices of Every Peerage. Vol. I. Longmans, Green.

- Fraser, Edward (1904). Famous Fighters of the Fleet: Glimpses Through the Cannon Smoke in the Days of the Old Navy. Kessinger Publishing.

- Hiscocks, Richard (2018). "Francis Reynolds-Moreton 3rd Lord Ducie". morethannelson. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Leach, Josiah Granville (1902). "Commodore John Hazlewood, Commander of the Pennsylvania Navy in the Revolution". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1902), pp. 1–6 and The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. 26 (1): 1–6. JSTOR 20086007.

- Martin, David G. (1993). Philadelphia Campaign. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-9382-8919-7.

- McGeorge, Wallace (1905). The Battle of Red Bank, resulting in the defeat of the Hessians and the destruction of the British frigate Augusta, Oct. 22 and 23, 1777. Camden, New Jersey, Sinnickson Chew, printers.

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign: Germantown and the Roads to Valley Forge. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4945-9.

- Miller, Nathan (2000). Broadsides. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-7858-2022-2.

- Mundy, Godfrey Basil (1830). The life and correspondence of the late Admiral Lord Rodney. London : J. Murray.

- Sparks, Jared, ed. (1853). Correspondence of the American revolution, being letters of eminent men to George Washington, from the time of his taking command of the army to the end of his presidency, Vol. II. Boston : Little, Brown and company.

Jared Sparks

- Wallace, John William (1884). An Old Philadelphian, Colonel William Bradford: The Patriot Printer of 1776. Sketches of His Life. Sherman & Company, printers. ISBN 9780795007507.

- "The story of the Battle of Red Bank". Friends of Redbank. Friends of Red Bank Battlefield. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- Harrison, Cy, ed. (2010). "Lord Francis Reynolds (3rd Baron Ducie)". Three Decks, Cy Harrison. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- "HMS Monarch". The London Gazette. No. 15354. 15 April 1801. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- "The London Gazette". No. 11967. 3 April 1779.

Further reading

- Black, Jeremy (1999). Warfare in the Eighteenth Century. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35245-6.

- Dull, Jonathan R (2009). The Age of the Ship of the Line: The British & French Navies, 1650–1815. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781473811669.

- Dunnavent, R. Blake (1998). Muddy Waters: A History of the United States Navy in Riverine Warfare and the Emergence of a Tactical Doctrine, 1775 – 1989 (Thesis). Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume I. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0178-5.

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume II. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-4945-9.

- "The Pennsylvania State Navy". USHistory.org. 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2016.