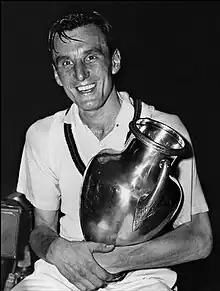

Fred Perry

Frederick John Perry (18 May 1909 – 2 February 1995) was a British tennis and table tennis player and former world No. 1 from England who won 10 Majors including eight Grand Slam tournaments and two Pro Slams single titles, as well as six Major doubles titles. Perry won three consecutive Wimbledon Championships from 1934 to 1936 and was World Amateur number one tennis player during those three years. Prior to Andy Murray in 2013, Perry was the last British player to win the men's Wimbledon championship, in 1936,[4] and the last British player to win a men's singles Grand Slam title, until Andy Murray won the 2012 US Open.

| |

| Full name | Frederick John Perry |

|---|---|

| Country (sports) | |

| Born | 18 May 1909 Portwood, Stockport, England |

| Died | 2 February 1995 (aged 85) Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Height | 6 ft (1.83 m)[1] |

| Turned pro | 1936 (amateur from 1929) |

| Retired | 1959 |

| Plays | Right-handed (one-handed backhand) |

| Int. Tennis HoF | 1975 (member page) |

| Singles | |

| Career record | 695–281 (71.2%)[2] |

| Career titles | 62[2] |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (1934, A. Wallis Myers)[3] |

| Grand Slam singles results | |

| Australian Open | W (1934) |

| French Open | W (1935) |

| Wimbledon | W (1934, 1935, 1936) |

| US Open | W (1933, 1934, 1936) |

| Professional majors | |

| US Pro | W (1938, 1941) |

| Wembley Pro | QF (1951, 1952) |

| Doubles | |

| Grand Slam doubles results | |

| Australian Open | W (1934) |

| French Open | W (1933) |

| Wimbledon | F (1932) |

| Grand Slam mixed doubles results | |

| French Open | W (1932) |

| Wimbledon | W (1935, 1936) |

| US Open | W (1932) |

| Team competitions | |

| Davis Cup | W (1933, 1934, 1935, 1936) |

Perry was the first player to win a "Career Grand Slam", winning all four singles titles, which he completed at the age of 26 at the 1935 French Championships. He remains the only British player ever to achieve this.[5] Perry's first love was table tennis and he was World Champion in 1929. He began playing tennis aged 14 and his tennis career at 21, when in 1930 an LTA committee chose him to join a four-man team to tour the United States.[5]

In 1933, Perry helped lead the Great Britain team to victory over France in the Davis Cup; the team's first success since 1912, followed by wins over the United States in 1934, 1935, and a fourth consecutive title with victory over Australia in 1936.[5] But due to his disillusionment with the class-conscious nature of the Lawn Tennis Club of Great Britain, the working-class Perry turned professional at the end of the 1936 season and moved to the United States where he became a naturalised U.S. citizen in 1939. In 1942, he was drafted into the US Army Air Force during the Second World War.[6]

Despite his unprecedented contribution to British tennis, Perry was not accorded full recognition by tennis authorities until later in life, because between 1927 and 1967 the International Lawn Tennis Federation ignored amateur champions who later turned professional.[4][7] In 1984, a statue of Perry was unveiled at Wimbledon, and in the same year he became the only tennis player listed in a survey of 2,000 Britons to find the "Best of the Best" British sportsmen of the 20th century.[7]

Early life

Perry was born in 1909 in Stockport, where his father, Samuel Perry (1877–1954), was a cotton spinner.[8] For the first decade of his life, he also lived in Bolton, Lancashire, and Wallasey, Cheshire, because his father was involved in local politics. When living in Wallasey he attended Liscard Primary School and, briefly, Wallasey Grammar School. Perry moved to Brentham Garden Suburb in Ealing, west London aged eleven years when his father became the national secretary of the Co-operative Party after World War I.[8] His father became the Labour and Co-operative Party Member of Parliament (MP) for Kettering in 1929.

Perry first began to play tennis on the public courts near his family's housing estate.[8] He was educated at Ealing Grammar School for Boys.

| Fred Perry | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Amateur career

During his amateur playing career Perry trained with Arsenal football club to focus on his fitness.[1]

1927

Perry was an eighteen year old table tennis protege when he began his tennis career. He reached several quarter finals of tennis events in the London area at Herga club in Harrow, Blackheath, Fulham and Ealing. He also reached the semi-finals at New Malden.[9]

1928

Perry reached the semi-finals at the Herga club tournament in Harrow in July.[10] He also reached the semi-finals of the Sidmouth tournament in September.[11]

1929

In 1929, a year when Perry won the World Table tennis championships, he continued his tennis career. He won the New Malden championships in August beating Wilfred Freeman in the final.[12] He also won Queen's Evening Tournament in December in Queen's Club, London, beating Horace Lester in the final.[13]

1930

Perry won the Middlesex championships in May beating Madan Mohan in the final[14] and the same month won the Harrogate championships beating John Olliff in the final.[15] In November, Perry beat Eric Peters in the final of the Argentine championships in Buenos Aires.[16]

1931

In April, Perry beat Ryuki Miki in the final of the Paddington championships in London.[17] In August, Perry won the Eastern grasscourt championships in Rye, New York beating Cliff Sutter in the semis and J. Gilbert Hall in the final.[18] In November, Perry beat Olliff in the final of the Cromer covered court autumn championships.[19]

1932

In January, Perry won the Coupe de Noel in Paris beating Marcel Bernard and Jean Borotra.[20] The following week, Perry beat Bernard in the final of the Flanders club event in Roubaix.[21] In February, Perry beat Pat Hughes in the final of the Kingston championships in Jamaica.[22] Then Perry beat Harry Lee in the final of the Bermuda championships.[23] Soon after returning to the UK in March, Perry beat Lee in the final of the Tally-Ho! Open Tennis Championships in Birmingham.[24] In April, Perry came from two sets down to beat George Lyttleton Rogers in the final of the British hardcourt championships in Bournemouth.[25] In May, Perry beat William Powell in the final of Harrogate championships.[26] In July, Perry won the Herga Club tournament beating Takeo Kuwabara in the final.[27] In September at the Pacific Southwest championships, Perry was 5–2 down in the final set and saved three match points before winning an epic quarter final 12–10 in the final set against Keith Gledhill.[28] He went on to beat Satoh to take the title.[29] Perry won the Pacific coast championships in October beating Bunny Austin in the final.[30]

1933

In May, Perry won the British hard court championships in Bournemouth over Adrian Quist,[31] Lee[32] and Austin[33] in the final three rounds. Perry denied Crawford the calendar Grand Slam and won his first Grand Slam title at the U.S. Championships. Crawford had a bad knee and "the Australian had to play a limping game at times on any quick starts or hard gets. In spite of this the tennis Fred Perry played deserved the title. He had the heart and used his head. His forcing strokes kept Crawford worried all afternoon. At any rate, leading two sets to one, Crawford had nothing left for the last two sets" according to The Hartford Courant.[34] In September, Perry won the Pacific Southwest championships beating Satoh in four sets in the final.[35] In November, whilst touring Australia, Perry played in the Victorian championships in Melbourne and beat Harry Hopman and Jack Crawford to take the title.[36]

1934

Perry beat Crawford in the final of the Australian championships in January and the British hardcourt championships in Bournemouth in May.[37] Perry won his first Wimbledon title beating defending champion Crawford in the final. Perry's success attracted the adoration of the crowds at Wimbledon particularly as he contrasted sharply with the privileged background of most patrons and players associated with the All England Club at the time. The upper echelons of the British tennis establishment greeted his success more coolly, regarding him as an "upstart". After winning his maiden Wimbledon title, Perry recalled overhearing a Wimbledon committee member remark that "the best man didn't win." His All-England Club member's tie, awarded to all winners of the Championships, was left for him on a chair in his dressing room.[38] Perry faced Wilmer Allison in the final of the U.S. Championships and when Perry led 5–2 in the fifth set "the crowd sighed in unison and looked toward the exits, but the Texan still wasn't through. He ripped to the net after his service balls to win one at love, and then he broke through Perry in the ninth. Allison held his own service in the 10th game and the count was five-all". However, Perry took the set and match 8–6.[39] Perry beat Stoefen in the final of the Pacific Southwest championships in September.[40] Perry beat Don Budge in five sets in the final of the Pacific Coast championships in October. Perry won "without going to the net more than a half dozen times in 50 games and when it was all over Budge had scored more points than his adversary, made fewer errors and many more placements".[41] Perry was ranked World No. 1 amateur by A. Wallis Myers,[42] Pierre Gillou,[43] Bernard Brown,[44] John R. Tunis,[45] Bill Tilden,[46] Ned Potter,[47] G.H. McElhone[48] (The Sydney Morning Herald), Harry Hopman,[49] R.O. Cummings (The Courier Mail),[50] and J. Brookes Fenno, Jr.[51] (The Literary Digest)

1935

Perry beat Abel Kay in the final of the New Zealand championships in January.[52] Perry beat Austin in five sets in the final of the British hardcourt championships in May.[53] Perry won the French championships in June to become the first man to win all four Grand Slam singles titles. In the final he beat Gottfried von Cramm in four sets. "The two hours final was conducted in perfect composure. It was essentially a sporting match, exhibiting beautiful tennis but lacking drama, because, after the second set. it was obvious that von Cramm could not pierce Perry's armour" according to a newspaper article.[54] Perry beat Hermann Artens in the final of the Belgian championships in Brussels in June.[55] Perry retained his Wimbledon title beating von Cramm in the final. "The German didn't like Perry's speed today. Nor did he care for the Englishman's eternal hustle which forced him to hurry his shots. Perry stayed close to the baseline save in the second set, for he saw that he could triumph without going to the net, thus exposing his wings to the German's favorite shot a razor-like drive down the sidelines."[56] Perry was ranked World No. 1 amateur by A. Wallis Myers,[57] S. Wallis Merrihew,[58] Pierre Gillou,[59] Harry Hopman,[60] Ned Potter,[61] G. H. McElhone,[62] The Times and[63] "Forehand" (Ashburton Guardian).[64][65]

1936

Perry beat Max Ellmer in the final of two Cannes championship titles (the Beau site event in March and the Cannes handicap tournament in April).[66] Perry beat Ladislav Hecht in the final of the Czech championships in Prague in April.[67] Perry beat Austin in straight sets in the final of the British hardcourt championships in Bournemouth in May to win his fifth consecutive British hardcourt title.[68] His Wimbledon final triumph was a 6–1, 6–1, 6–0 victory over the German Baron Gottfried von Cramm which lasted less than 45 minutes. It became the quickest final in the 20th century and the second shortest of all time. Perry had learned from the Wimbledon masseur that von Cramm had suffered a groin strain which limited his ability to move wide on the forehand.[69] Perry faced Budge in the final of the U.S. Championships. At 5-4 and 8–7 in the fifth set, Budge came within two points of victory at Deuce on Perry's serve. "Verging on victory, the pressure weighed heavily on the slightly built, elongated American, while Perry, an experienced campaigner, remained cool", according to Chicago Tribune. Perry won the fifth set 10-8 and with it his eighth and last Grand Slam singles title.[70]

In the Davis Cup, Perry led the Great Britain team to four consecutive victories from 1933 to 1936, with wins over France in 1933, the United States in 1934 and 1935, and Australia in 1936. Perry competed in a total of 20 Davis Cup matches, winning 34 of his 38 rubbers in singles, and 11 out of 14 in doubles.[5]

Perry was ranked World No. 1 amateur by A. Wallis Myers,[71] Pierre Gillou,[72] Ned Potter,[73] The Times,[74] Harry Hopman,[75] "Austral" (R.M. Kidston),[76] G.H. McElhone,[77] Mervyn Weston[74] (The Australasian) and Bill Tilden.[78]

Professional career

1937

After three years as the world No. 1 tennis amateur player, Perry turned professional in late 1936. This led to his being virtually ostracised by the British tennis establishment.[8] He made his professional debut on 6 January 1937 at the Madison Square Garden against the best professional player, Ellsworth Vines, winning in four sets.[79][80] For the next two years he played lengthy tours against Vines. In 1937, they played 61 matches in the United States on their big tour, with Vines winning 32 and Perry 29.[81] They then sailed to Britain, where they played a brief tour in UK and Ireland. Perry won the King George VI Coronation Cup over Vines.[82] Perry won six matches out of nine in UK and Ireland, so Vines and Perry finished the year tied at 35 victories each. Ray Bowers ranked Perry and Vines joint no. 1 pros for 1937.[83]

1938

The following year, 1938, the big tour was even longer, and this time Vines beat Perry 49 matches to 35, while a short tour of the Caribbean and Central and South America ended at four victories a piece. Perry won the U.S. Pro at Chicago beating Bruce Barnes in the final.[84]

1939

Don Budge won the Grand Slam in 1938 as an amateur and then turned professional and played a series of matches against both Vines and Perry in 1939, beating Vines 22 times to 17, and beating Perry by 28 victories to 8.[85][86][87] In October, Perry lost in the final of U.S. Pro to Vines in four sets.[88] Then Perry won a four-man round robin at Long Beach (he, Gorchakoff and Stoefen finished level on 2 wins each). He also won a four-man round robin in San Diego in November (where he and Stoefen finished on two wins each).[89] In December he won four man round robins at Phoenix[90] and Pasadena.[91]

1940

Perry won the Finnish relief event in New York in March, beating Vines and Budge.[92] Perry won West Coast Pro round robin in Los Angeles[93] in April. This was the last time Perry and Vines played each other before Vines embarked full time on a golf career. Perry won their final match. Perry lost in the final of the U.S. Pro in Chicago to Budge.[94]

1941

In April Perry won tournaments at Pinehurst (over Dick Skeen) and White Sulphur Springs (over Skeen).[94] Perry beat Skeen again in the final of the U.S. Pro at Chicago in June and also in June, Perry won a four-man round robin at Forest Hills over Budge, Skeen and Tilden and won an event at Rye (beating Skeen in the final).[94] In August Perry won a four-man round robin at St. Louis.[95] Perry was ranked World No. 1 pro by Ray Bowers.[96]

1942-1945

After breaking his elbow in a match against Bobby Riggs on the opening night of the Round robin World Series, Perry had to miss several matches of the tour. Perry finished fourth in the standings.[97] Soon after the pro circuit petered out in mid-1942, Perry was involved in World War 2, where he served in the U.S. Air force,[98] having already gained American citizenship in 1939.

1946

In 1946, Perry won events at Tucson in January (beating Bobby Riggs in the final), Omaha in February (beating Wayne Sabin in the final), Palm Springs in April (over Carl Earn) and El Paso in May (over Frank Kovacs).[99] Perry also played a series of matches against Tilden.[100]

1947

In June, Perry lost in the quarter-finals of the U.S. Pro to Van Horn. In August Perry won the White Mountains Pro at Jefferson beating Sabin in the final.[101]

1948

Perry won the Slazenger Pro at Scarborough in July. In the final he won in four sets against Yvon Petra,[102] who had won the Wimbledon men's singles two years earlier. "Perry, noted one observer, had lost none of his zest, sting—or shrewdness. Perry assessed Petra's game while losing the first set of the final and won the next three for the loss of seven games. 'I knew a little bit more about the game than he did', said Perry afterwards."[103]

1949

Perry turned 40 in May. By now, Perry was playing on the pro circuit sporadically. Defending his title at Scarborough in July, Perry lost in the quarter-finals to Dinny Pails in five sets.[104]

1950-1959

Perry won the Slazenger Pro at Scarborough in August 1950, beating Salem Khaled in the final.[105] In August 1951, aged 42, Perry won his final title at Scarborough beating Francesco Romanoni.[106] Perry won a tournament at Hagen in September 1953 beating fellow veteran Hans Nusslein in the final.[107] He continued playing until he was 50 in 1959, when he lost in the first round of the U.S. Pro at Cleveland.[108]

Table tennis career

"Perry took advantage of his athletic build and extraordinary physical capacity: he was highly mobile and fast, had a sound defence and placed his balls very well. Thanks to his very strong wrist he could hit a very hard forehand drive".[109] Perry reached the quarter-finals of the men's singles in the 1928 Stockholm World championships, where he lost to Laszlo Bellak.[109] He was runner-up in the men's doubles with Charlie Bull. In 1929 Perry lost to Bull in the Czechoslovak Open and lost to Anton Malacek in the English Open.[109] At the Budapest World championships men's singles event, Perry beat Miklós Szabados 3 games to 1 to win the title.[110] He beat Szabados again in an exhibition in Paris. His final table tennis appearance was in 1932, in a team match in London against Hungary.[109]

Broadcasting career

Fred Perry had a long career as a tennis broadcaster. He worked as a summariser and reporter for BBC Radio from 1959[111] to 1994[112] and for many years was a familiar voice during BBC radio's coverage of Wimbledon. He also commentated on TV on the BBC from 1951 to 1952 and ITV's coverage of Wimbledon from 1956 to 1968, after which ITV stopped broadcasting the championships. ITV "employed me as a would-be counter-attraction to my old friend Dan Maskell on BBC Television. We were simply not able to compete and I wasn't unhappy when ITV gave it up as a bad job. The BBC had two channels to ITV's one, and were not inhibited by commercial breaks every fifteen minutes and the imposition of a strict time limit on the coverage, as ITV was", explained Perry in his autobiography.[113] In later years, Perry was sometimes interviewed by BBC Television during their Wimbledon coverage. In 1979 Perry spoke to Des Lynam at Wimbledon about his life in an episode of the TV series "Maestro". The programme was shown again as a tribute after his death.

Personal life

Perry was one of the leading bachelors of the 1930s and his off-court romances were reported in the world press. Perry had a romantic relationship with actress Marlene Dietrich and in 1934 he announced his engagement to British actress Mary Lawson, but the relationship fell apart after Perry moved to the US. In 1935 he married American film star Helen Vinson, but their marriage ended in divorce in 1940. In 1941 he was briefly married to model Sandra Breaux. Then, in 1945, he married Lorraine Walsh, but that marriage also ended quickly. Perry's final marriage to Barbara Riese (the sister of actress Patricia Roc) in 1952 lasted over forty years, until his death. They had two children, Penny and David. David led his father's clothing line prior to a buyout.

In July 1937, an England vs America pro-celebrity tennis doubles match was organized, featuring Perry and Charlie Chaplin playing against Groucho Marx and Ellsworth Vines, to open the new clubhouse at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club.[114]

Perry had an older sister, Edith; they were both born in Stockport, Cheshire. Edith greatly supported her younger brother throughout his sporting achievements. Perry had a half sister, Sylvia.[115]

Death

Perry died at Epworth Hospital in Melbourne, Australia, after breaking his ribs following a fall in a hotel bathroom.[116]

Sporting legacy

Perry is considered by some to have been one of the greatest players ever to have played the game. In his 1979 autobiography Jack Kramer, the long-time tennis promoter and great player himself, called Perry one of the six greatest players of all time.[117] In 1975, Don Budge ranked his top five players of all time and rated Perry number three behind Vines and Kramer.[118]

Kings of the Court, a video-tape documentary made in 1997 in conjunction with the International Tennis Hall of Fame, named Perry one of the ten greatest players of all time. But this documentary only considered those players who played before the Open era of tennis that began in 1968, with the exception of Rod Laver, who spanned both eras, so that all of the more recent great players are missing.

In 100 Greatest of All Time, a 2012 television series broadcast by the Tennis Channel, Perry was ranked the 15th-greatest male player, just behind Boris Becker at 14th, and just ahead of Stefan Edberg at 16th. Perry's great rivals Vines (37th) and Crawford (32nd) were ranked well below him.[119]

Kramer, however, had several caveats about Perry. He says that Bill Tilden once called Perry "the world's worst good player". Kramer says that Perry was "extremely fast; he had a hard body with sharp reflexes, and he could hit a forehand with a snap, slamming it on the rise—and even on the fastest grass. That shot was nearly as good as Segura's two-handed forehand." His only real weakness, says Kramer, "was his backhand. Perry hit underslice off that wing about 90% of the time, and eventually at the very top levels—against Vines and Budge—that was what did him in. Whenever an opponent would make an especially good shot, Perry would cry out 'Very clevah.' I never played Fred competitively, but I heard enough from other guys that 'Very clevah' drove a lot of opponents crazy."

Perry, however, recalled his days on the professional tour differently. He maintained that "there was never any easing up in his tour matches with Ellsworth Vines and Bill Tilden since there was the title of World Pro Champion at stake." He said "I must have played Vines in something like 350 matches, yet there was never any fixing as most people thought. There were always people willing to believe that our pro matches weren't strictly on the level, that they were just exhibitions. But as far as we were concerned, we always gave everything we had."[120]

Another comment from Kramer is that Perry unwittingly "screwed up men's tennis in England, although this wasn't his fault. The way he could hit a forehand—snap it off like a ping-pong shot—Perry was a physical freak. Nobody else could be taught to hit a shot that way. But the kids over there copied Perry's style, and it ruined them. Even after Perry faded out of the picture, the coaches there must have kept using him as a model."

Clothing label

In the late 1940s, Perry was approached by Tibby Wegner, an Austrian footballer who had invented an anti-perspirant device worn around the wrist. Perry made a few changes to create the first sweatband.

Wegner's next idea was to produce a sports shirt, which was to be made from white knitted cotton pique with short sleeves and a buttoned placket like René Lacoste's shirts. Launched at Wimbledon in 1952, the Fred Perry tennis shirt was an immediate success.[8] Initially it was only available in two colours—white and black.[121] The brand's logo is a laurel wreath. It was based on the original symbol for Wimbledon.[8] The logo, which appears on the left breast of Fred Perry garments, is stitched into the fabric of the shirt.[122]

The white tennis shirt was supplemented in the late 1950s with coloured versions for table tennis, in which white shirts are not allowed. These became popular in the 1960s as a symbol of mod culture. The brand had been associated with skinheads and the National Front in the 1970s.[123] During the mid-1990s, its popularity in the United Kingdom was revived due to its association with the band Blur.[124][125] In France, the brand is popular with both the far right and far left.[126]

The brand was initially run by the Perry family, namely his son David, until it was bought by Japanese company Hit Union in 1995. However, the Perry family continued to work closely with the brand.[127][128]

The brand was the clothing sponsor of British tennis player Andy Murray from the start of his career until 2009.[129]

From September 2019,[130] Perry stopped selling its black and yellow polo shirts across North America after they became the "unofficial uniform" of the far-right organisation Proud Boys,[123][131][132] and called on Proud Boys members to stop wearing its clothing.[133][134]

Honours and memorials

United Kingdom

A bronze statue of Fred Perry was erected at the All England Lawn Tennis Club in Wimbledon, London, in 1984 to mark the 50th anniversary of his first singles championship. It is located at the Church Road gate. After Perry's accidental death in 1995, he was cremated and his ashes buried in an urn near the statue.

Perry's home town of Stockport has numerous memorials to the former tennis champion. For instance there is a blue plaque commemorating the house where he was born. In September 2002, a designated walking route called the Fred Perry Way was opened through the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport. The 14-mile (23 km) route from Woodford in the south to Reddish in the north, combines rural footpaths, quiet lanes and river valleys with urban landscapes and parklands. Features along the route include Houldsworth Mill and Square, the start of the River Mersey at the confluence of the River Tame and River Goyt, Stockport Town Centre, Vernon and Woodbank Parks and the Happy Valley. The route also passes through Woodbank Park, where Perry played some exhibition tennis matches.

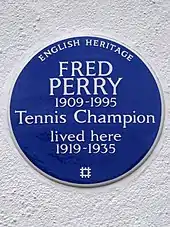

In 2009, Perry was selected by the Royal Mail for their "Eminent Britons" commemorative postage stamp issue.[135] In November 2010, Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex and John Perry, Fred Perry's grandson, opened Fred Perry House in Stockport. The building, which is the borough's new civic headquarters, will be used by various local government agencies.[136] In June 2012, an English Heritage blue plaque was unveiled on the house at 223 Pitshanger Lane, Ealing, London, where Perry lived between 1919 and 1935.

World

Perry was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1975.

Perry received a Doctor of Laws degree, honoris causa, from Washington and Lee University on 4 June 1987.[137] He had coached the W&L tennis team in 1941 and again in 1947.[138]

In the United States, two drives in El Paso, Texas, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and a street in Springfield, Tennessee, are named after Fred Perry.

World Table Tennis Championships

- Gold 1; Silver 1; Bronze 4

- 1928 Stockholm: Silver Doubles; Bronze Mixed Doubles; Bronze Team

- 1929 Budapest: Gold Singles; Bronze Doubles; Bronze Team

Major finals

Singles: 10 (8 titles, 2 runners-up)

| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Opponent | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1933 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 6–3, 11–13, 4–6, 6–0, 6–1 | |

| Win | 1934 | Australian Championships | Grass | 6–3, 7–5, 6–1 | |

| Win | 1934 | Wimbledon Championships | Grass | 6–3, 6–0, 7–5 | |

| Win | 1934 | U.S. Championships (2) | Grass | 6–4, 6–3, 3–6, 1–6, 8–6 | |

| Loss | 1935 | Australian Championships | Grass | 6–2, 4–6, 4–6, 4–6 | |

| Win | 1935 | French Championships | Clay | 6–3, 3–6, 6–1, 6–3 | |

| Win | 1935 | Wimbledon Championships (2) | Grass | 6–2, 6–4, 6–4 | |

| Loss | 1936 | French Championships | Clay | 0–6, 6–2, 2–6, 6–2, 0–6 | |

| Win | 1936 | Wimbledon Championships (3) | Grass | 6–1, 6–1, 6–0 | |

| Win | 1936 | U.S. Championships (3) | Grass | 2–6, 6–2, 8–6, 1–6, 10–8 |

Doubles: 4 (2 titles, 2 runners-up)

| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Partner | Opponents | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss | 1932 | Wimbledon Championships | Grass | 6–0, 4–6, 3–6, 7–5, 7–5 | ||

| Win | 1933 | French Championships | Clay | 6–2, 6–4, 2–6, 7–5 | ||

| Win | 1934 | Australian Championships | Grass | 6–8, 6–3, 6–4, 3–6, 6–3 | ||

| Loss | 1935 | Australian Championships | Grass | 6–4, 8–6, 6–2 |

Mixed doubles: 5 (4 titles, 1 runner-up)

| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Partner | Opponents | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1932 | French Championships | Clay | 6–4, 6–2 | ||

| Win | 1932 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 6–3, 7–5 | ||

| Loss | 1933 | French Championships | Clay | 2–6, 3–6 | ||

| Win | 1935 | Wimbledon Championships | Grass | 7–5, 4–6, 6–2 | ||

| Win | 1936 | Wimbledon Championships | Grass | 7–9, 7–5, 6–4 |

4 finals (2 titles, 2 runners-up)

| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Opponent | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1938 | US Pro | Indoor | 6–3, 6–2, 6–4 | |

| Loss | 1939 | US Pro | Hard | 6–8, 8–6, 1–6, 18–20 | |

| Loss | 1940 | US Pro | Clay | 3–6, 7–5, 4–6, 3–6 | |

| Win | 1941 | US Pro | Clay | 6–4, 6–8, 6–2, 6–3 |

Performance timeline

Fred Perry joined professional tennis in 1937 and was unable to compete in the Grand Slams tournaments.

| W | F | SF | QF | #R | RR | Q# | DNQ | A | NH |

| Tournament | Amateur career | Professional career | SR | W–L | Win % | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| '29 | '30 | '31 | '32 | '33 | '34 | '35 | '36 | '37 | '38 | '39 | '40 | '41 | '42 | '43 | '44 | '45 | '46 | '47 | '48 | '49 | '50 | '51 | '52 | '53 | '54 | '55 | '56 | '57 | '58 | '59 | ||||

| Grand Slam tournaments: | 8 / 23 | 101–15 | 87.07 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australian | A | A | A | A | A | W | F | A | A | A | A | A | Not held | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 1 / 2 | 9–1 | 90.00 | ||||

| French | A | A | 4R | QF | QF | QF | W | F | A | A | A | Not held | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 1 / 6 | 22–5 | 81.48 | ||||

| Wimbledon | 3R | 4R | SF | QF | 2R | W | W | W | A | A | A | Not held | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 3 / 8 | 36–5 | 87.80 | |||||

| U.S. | A | 4R | SF | 4R | W | W | SF | W | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 3 / 7 | 34–4 | 89.47 |

| Pro Slam tournaments: | 2 / 11 | 19–9 | 67.86 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Pro | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | W | F | F | W | A | A | NH | A | QF | QF | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | QF | A | A | 1R | 1R | 2 / 9 | 17–7 | 70.83 |

| French Pro | NH | A | A | A | NH | A | A | A | A | A | A | Not held | A | NH | A | A | 0 / 0 | 0–0 | N/A | |||||||||||||||

| Wembley Pro | Not held | A | A | NH | A | NH | A | Not held | A | A | QF | QF | A | NH | A | A | A | A | 0 / 2 | 2–2 | 50.00 | |||||||||||||

| Total: | 10 / 34 | 120–24 | 83.33 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Peter Jackson (3 July 2009). "Who was Fred Perry?". BBC. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Fred Perry: Career match record". thetennisbase.com. Tennis Base. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "Myers Seeds Fred Perry No. One; But Three Yanks Place", The Lewiston Daily Sun, 13 September 1934.

- "Fred Perry, Wimbledon's true champion, dies at 85". The Independent. 3 February 1995. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "Fred Perry – Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- "Who was Fred Perry?". BBC. 3 July 2009. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- Fred Perry: the icon and the outcast BBC History Magazine. Retrieved 27 June 2011

- Peter Jackson (3 July 2009). "Who was Fred Perry?". BBC News. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- Daily Mirror, 27 August 1927, p.19

- Daily News (London), 20 July 1928, p.15

- Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 8 September 1928, p.2

- Sunday Mirror, 1 September 1929, p.27

- Daily News (London), 2 December 1929, p.13

- Sunday Mirror, 1 June 1930, p.27

- Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 12 May 1930, p.15

- Daily Herald, 17 November 1930, p.15

- Illustrated Sporting and dramatic news, 11 April 1931, p.11

- "Evening Sun". 17 August 1931 – via Newspapers.com.

- Middlesex County Times, 14 November 1931, p.15

- Sheffield Independent, 4 January 1932, p.11

- Leeds Mercury, 12 January 1932, p.9

- Hull Daily Mail, 13 February 1932, p.8

- "The Argus". 4 March 1932 – via Trove.

- Daily Mirror, 31 March 1932, p.23

- Reynolds's newspaper, 1 May 1932, p.22

- Leeds Mercury, 9 May 1932, p.11

- Reynolds's Newspaper, 17 July 1932, p.22

- "Pasadena Post". 23 September 1932 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The State". 25 September 1932 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Gazette". 3 October 1932 – via Newspapers.com.

- Western Daily Press, 4 May 1933, p.4

- Nottingham Journal, 5 May 1933, p.11

- Yorkshire Post and intelligencer, 8 May 1933, p.14

- "Hartford Courant". 11 September 1933 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Miami Herald". 24 September 1933 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Western Mail". 30 November 1933 – via Trove.

- The Scotsman, 7 May 1934, p.8

- "Why tennis establishment shunned Fred Perry, Britain's previous Wimbledon men's winner in 1936". The Independent. 7 July 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "The Gazette (Montreal)". 13 September 1934 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Akron Beacon Journal". 25 September 1934 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Oakland Tribune". 8 October 1934 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Von Cramm Badly Treated in World Tennis Ranking". Sporting Globe. No. 1266. Victoria, Australia. 19 September 1934. p. 11 (Edition2). Retrieved 22 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "M. Gillou donne à L'Auto son classement pour 1934" [Mr. Gillou gives his 1934 ranking to L'Auto]. L'Auto (in French). 14 September 1934. pp. 1, 4.

- Brown, Bernard (14 September 1934). "Perry Earned Undisputed Right to 1934 World's No. 1 Tennis Ranking". Brooklyn Times-Union. p. 15.

- Tunis, John R. (4 December 1934). "Critic Ranks Pro Net Stars Over Amateurs". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 18.

- "Tilden's World Rankings". Wairarapa Daily Times. 27 August 1934. p. 5.

- "First 20 Players". The Advertiser (Adelaide). South Australia. 4 January 1935. p. 10. Retrieved 28 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "LAWN TENNIS". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 30, 171. New South Wales, Australia. 14 September 1934. p. 11. Retrieved 4 December 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "HOPMAN'S "FIRST 10"". The Herald (Melbourne). No. 18, 201. Victoria, Australia. 16 September 1935. p. 24. Retrieved 25 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "WORLD'S TENNIS STARS RANKED". The Courier-Mail. No. 327. Queensland, Australia. 14 September 1934. p. 11. Retrieved 28 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "TEN AT THE TOP IN TENNIS". Crookwell Gazette. Vol. LI, no. 8. New South Wales, Australia. 16 January 1935. p. 3. Retrieved 24 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "The Courier-Mail". 31 January 1935 – via Trove.

- The Scotsman, 6 May 1935, p.6

- "The Sydney Morning Herald". 4 June 1935 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Guardian". 11 June 1935 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Californian". 5 July 1935 – via Newspapers.com.

- "CRAWFORD SECOND". Daily Standard. No. 7099. Queensland, Australia. 18 October 1935. p. 5. Retrieved 22 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "25 Years Ago". World Tennis. Vol. 8, no. 5. New York. October 1960. p. 49.

- "Le classement des dix meilleurs joueurs de tennis du monde par M. Pierre Gillou" [The ranking of the world's ten best tennis players by Mr. Pierre Gillou]. L'Auto (in French). 15 September 1935. pp. 1, 5.

- "HOPMAN'S "FIRST 10"". The Herald (Melbourne). No. 18, 201. Victoria, Australia. 16 September 1935. p. 24. Retrieved 22 April 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- "The World's First Ten: How The World's Best Were Rated From 1914 To The Present". World Tennis. Vol. 16, no. 5. New York. October 1968. pp. 32–33.

- "FIRST TEN". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 30, 485. New South Wales, Australia. 17 September 1935. p. 9. Retrieved 28 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "World Tennis Stars: The Ranking List". Poverty Bay Herald. Vol. 62, no. 18819. 24 September 1935. p. 5.

- "A World Ranking List. The Ten Best Men". Ashburton Guardian. Vol. 55, no. 307. 10 October 1935. p. 9.

- "A World Ranking List. The Ten Best Men". Ashburton Guardian. Vol. 56, no. 4. 17 October 1935. p. 7.

- "Brooklyn Times Union". 5 April 1936 – via Newspapers.com.

- "The Advocate (Burnie)". 25 April 1936 – via Trove.

- The Scotsman, 4 May 1936, p.6

- Fred Perry: An autobiography, 1984, p.100-101

- "Chicago Tribune". 13 September 1936 – via Newspapers.com.

- "World Tennis Players". The Age. 24 September 1936. p. 6 – via National Library of Australia.

- "M. Pierre Gillou donne à L'Auto ses classements masculin et féminin" [Mr. Pierre Gillou gives his men's and women's rankings to L'Auto]. L'Auto (in French). 16 September 1936. pp. 1, 3.

- "LAWN TENNIS". The Examiner (Tasmania). Vol. XCV, no. 250. Tasmania, Australia. 1 January 1937. p. 2 (DAILY). Retrieved 28 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "LAWN TENNIS". The Australasian. Vol. CXLI, no. 4, 577. Victoria, Australia. 26 September 1936. p. 31. Retrieved 17 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "World tennis players". The Newcastle Sun. 18 September 1936. p. 7 – via National Library of Australia.

- "RANKING THE WORLD'S BEST TENNIS PLAYERS". The Referee. No. 2576. New South Wales, Australia. 6 August 1936. p. 17. Retrieved 4 December 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- "TWO LISTS". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 30, 797. New South Wales, Australia. 16 September 1936. p. 19. Retrieved 28 November 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- Tilden, William T. (7 January 1937). "Bill Tilden Says: Perry Unquestionably Leading Amateur Tennis Player of Year—Budge And Grant Are the Only Americans Who Belong in First Ten". The Boston Globe. p. 24.

- Magill, Frank N., ed. (1999). Dictionary of World Biography (1. ed.). Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 2979–2982. ISBN 978-1579580483.

- "Perry Wins First Match as Professional". Kalgoorlie Miner. 22 January 1937. p. 8.

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.29

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.184

- Bowers, Ray. "History of the Pro Tennis Wars, Chapter VIII: Perry and Vines, 1937" – via tennisserver.com.

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.185

- "BUDGE WINS, 6–2, 6–2, 6–3; Don Beats Vines in Montreal and Will Arrive Here Today". The New York Times. 7 March 1939. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- "BUDGE TRIUMPHS, 8–6, 6–2; Don Beats Perry for 28th Time at White Plains". The New York Times. 9 May 1939. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- The Bud Collins History of Tennis: An Authoritative Encyclopedia and Record Book. New Chapter Press. 2008. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-942257-41-0.

- "Arizona Republic". 23 October 1939 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Oakland Tribune". 27 November 1939 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Arizona Republic". 11 December 1939 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Los Angeles Times". 18 December 1939 – via Newspapers.com.

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.186

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.24

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.187

- "St. Louis Post-Dispatch". 4 August 1941 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bowers, Ray. "History of the Pro Tennis Wars, Chapter XI: America 1940-1941" – via tennisserver.com.

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.37

- "Fred Perry: The hero from the wrong side of the tramlines". 21 November 2015 – via independent.co.uk.

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.189-190

- "Palm Beach Post". 24 February 1946 – via Newspapers.com.

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.192

- Coventry Evening Telegraph, 31 July 1948, p.16

- The last champion: The life of Fred Perry, Jon Henderson, 2009

- Bradford Observer, 29 July 1949, p.6

- Dundee Courier, 7 August 1950, p.2

- Evening Herald (Dublin), 6 August 1951, p.6

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.200

- The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.212

- ITTF 1926-2001 Table Tennis Legends, Zdenko Uzorinac, ITTF, 2001, p.41

- The Times (London), 22 January 1929, p.6

- "Sports session – BBC Home service – 4 July 1959, BBC Genome". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk.

- "Wimbledon 94 – Radio 5 – 21 June 1994, BBC Genome". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk.

- Fred Perry: An autobiography (1984), p. 191

- "The Marx brothers on film: souped-up comedy". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Doward, Jamie (10 May 2009). "How Britain's prince of tennis wooed Hollywood's top stars". The Observer. London. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- Burton, Mark (3 February 1995). "Fred Perry, Wimbledon's true champion, dies at 85". The Independent. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Writing in 1979, Kramer considered the best ever to have been either Don Budge (for consistent play) or Ellsworth Vines (at the height of his game). The next four best were, chronologically, Bill Tilden, Fred Perry, Bobby Riggs and Pancho Gonzales. After these six came the "second echelon" of Rod Laver, Lew Hoad, Ken Rosewall, Gottfried von Cramm, Ted Schroeder, Jack Crawford, Pancho Segura, Frank Sedgman, Tony Trabert, John Newcombe, Arthur Ashe, Stan Smith, Björn Borg and Jimmy Connors. He felt unable to rank Henri Cochet and René Lacoste accurately but felt they were among the very best.

- "The South Bend Tribune, 10 August 1975". newspapers.com.

- "The List ::Tennis Channel". tennischannel.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- The History of Professional Tennis, Joe McCauley.

- "FRED PERRY - Casual International". Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Fred Perry Logo: Design and History Archived 13 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. FamousLogos.net. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- Woolf, Jake (11 July 2017). "Fred Perry Wants Alt-Right Bros to Stop Wearing Their Polos". GQ Magazine. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Fashion … or fascist? The long tussle over that Fred Perry logo. The Guardian. 4 October 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- The many projects of Damon Albarn. AFP. 19 February 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- "Skinheads, anti-fascists and the Fred Perry connection". France 24. 7 June 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- The Independent, Everyone for tennis: Fred Perry celebrates 60 years as a sportswear icon 13 October 2012

- David Owen, Fred Perry's surprise big hit Financial Times, 14 November 2005

- "Murray ends Fred Perry sponsorship deal". The Independent. 4 November 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- "Proud Boys Statement". fredperry.com. 24 September 2020.

- "Fred Perry stops selling polo shirt after it becomes associated with far-right group". Sky News. 28 September 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Miller-Idriss, Cynthia (29 August 2019). "Why does the far right love Fred Perry? Mainstream fashion is its new camouflage". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- Matthers, Matt (26 September 2020). "Proud Boys Portland rally: Fred Perry tells right-wing group to stop wearing its iconic T-shirts". The Independent. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- "Proud Boys love Fred Perry polo t-shirts. The feeling is not mutual". The Washington Post. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- "The Royal Mail celebrate eminent Britons". The Times. Retrieved 30 September 2022.

- "Official Opening of Fred Perry House". Stockport Council. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- "Washington and Lee honorary degrees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- Ring-tum Phi, Washington and Lee student newspaper, and Calyx, Washington and Lee student yearbook,

Bibliography

- McCauley, Joe (2003). The History of Professional Tennis.