Ouabain

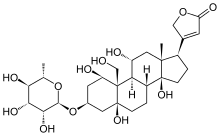

Ouabain /wɑːˈbɑːɪn/[1] or /ˈwɑːbeɪn, ˈwæ-/ (from Somali waabaayo, "arrow poison" through French ouabaïo) also known as g-strophanthin, is a plant derived toxic substance that was traditionally used as an arrow poison in eastern Africa for both hunting and warfare. Ouabain is a cardiac glycoside and in lower doses, can be used medically to treat hypotension and some arrhythmias. It acts by inhibiting the Na/K-ATPase, also known as the sodium–potassium ion pump.[2] However, adaptations to the alpha-subunit of the Na+/K+-ATPase via amino acid substitutions, have been observed in certain species, namely some herbivore- insect species, that have resulted in toxin resistance.[3]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Strodival |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.010.128 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C29H44O12 |

| Molar mass | 584.659 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[4]

Sources

Ouabain can be found in the roots, stems, leaves, and seeds of the Acokanthera schimperi and Strophanthus gratus plants, both of which are native to eastern Africa.[5]

Acokanthera schimperi plant |

.JPG.webp) Strophanthus gratus plant |

Mechanism of action

Ouabain is a cardiac glycoside that acts by inhibiting the Na+/K+-ATPase sodium–potassium ion pump (but it is not selective).[2] Once ouabain binds to this enzyme, the enzyme ceases to function, leading to an increase of intracellular sodium. This increase in intracellular sodium reduces the activity of the sodium–calcium exchanger (NCX), which pumps one calcium ion out of the cell and three sodium ions into the cell down their concentration gradient. Therefore, the decrease in the concentration gradient of sodium into the cell which occurs when the Na/K-ATPase is inhibited reduces the ability of the NCX to function. This in turn elevates intracellular calcium.[6] This results in higher cardiac contractility and an increase in cardiac vagal tone. The change in ionic gradients caused by ouabain can also affect the membrane voltage of the cell and result in cardiac arrhythmias.

Symptoms

An overdose of ouabain can be detected by the presence of the following symptoms: rapid twitching of the neck and chest musculature, respiratory distress, increased and irregular heartbeat, rise in blood pressure, convulsions, wheezing, clicking, and gasping rattling. Death is caused by cardiac arrest.[5]

Toxicology

Ouabain is a highly toxic compound, however, it has a low bioavailability[2] and is absorbed poorly from the alimentary tract as so much of the oral dose is destroyed. Intravenous administration results in greater available concentrations. After intravenous administration, the onset of action occurs within 2–10 minutes in humans with the maximum effect enduring for 1.5 hours.

Ouabain is eliminated by renal excretion, largely unchanged.[2]

Biological effects

Endogenous ouabain

In 1991, a specific high affinity sodium pump inhibitor indistinguishable from ouabain was first discovered in the human circulation [7] and proposed as one of the potential mediators of long term blood pressure and the enhanced salt excretion following salt and volume loading.[8] This agent was an inhibitor of the sodium pump that acted similarly to digitalis. A number of analytical techniques led to the conclusion that this circulating molecule was ouabain and that humans were producing it as an endogenous hormone.[8] A large portion of the scientific community agreed that this inhibitor was endogenous ouabain and that there was strong evidence to indicate that it was synthesized in the adrenal gland.[8] One early speculative interpretation of the analytical data led to the proposal that endogenous ouabain may have been the 11 epimer, i.e., an isomer of plant ouabain.[9] However, this possibility was excluded by various methods including the synthesis of the 11 epimer and the demonstration that it has different chromatographic behavior from ouabain. Critically, the primary observations concerning the identification of ouabain in mammals were repeated and confirmed using a variety of tissue sources on three different continents with advanced analytical methods as summarized elsewhere [10]

Despite widespread analytical confirmation, some questioned whether or not this endogenous substance is ouabain. The arguments were based less upon rigorous analytical data but more on the fact that immunoassays are neither entirely specific nor reliable. Hence, it was suggested that some assays for endogenous ouabain detected other compounds or failed to detect ouabain at all.[11] Additionally, it was suggested [11] that rhamnose, the L-sugar component of ouabain, could not be synthesized within the body despite published data to the contrary.[12] Yet another argument against the existence of endogenous ouabain was the lack of effect of rostafuroxin (a first generation ouabain receptor antagonist) on blood pressure in an unselected population of hypertensive patients.[13]

Medical uses

Ouabain is no longer approved for use in the USA. In France and Germany, however, intravenous ouabain has a long history in the treatment of heart failure, and some continue to advocate its use intravenously and orally in angina pectoris and myocardial infarction despite its poor and variable absorption. The positive properties of ouabain regarding the prophylaxis and treatment of these two indications are documented by several studies.[14][15]

Animal use of ouabain

The African crested rat (Lophiomys imhausi) has a broad, white-bordered strip of hairs covering an area of glandular skin on the flank. When the animal is threatened or excited, the mane on its back erects and this flank strip parts, exposing the glandular area. The hairs in this flank area are highly specialised; at the tips they are like ordinary hairs, but are otherwise spongy, fibrous, and absorbent. The rat is known to deliberately chew the roots and bark of the Poison-arrow tree (Acokanthera schimperi), which contains ouabain. After the rat has chewed the tree, instead of swallowing the poison it slathers the resulting masticate onto its specialised flank hairs which are adapted to absorb the poisonous mixture. It thereby creates a defense mechanism that can sicken or even kill predators which attempt to bite it.[16][17][18]

Synthesis

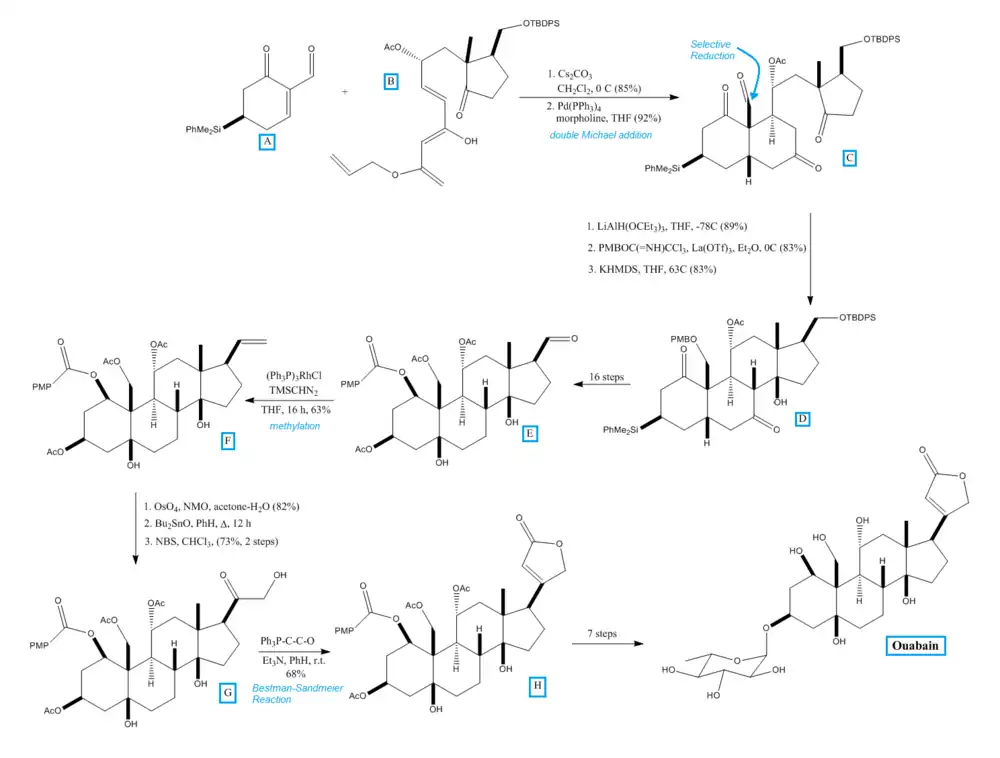

The total synthesis of ouabain was achieved in 2008 by Deslongchamps laboratory in Canada.[19] It was synthesized under the hypothesis that a polyanionic cyclization (double Michael addition followed by aldol condensation) would allow access to a tetracyclic intermediate with the desired functionality.[19] The figure below shows the key steps in the synthesis of ouabain.

In their synthesis, Zhang et al. from the Deslongchamps laboratory condensed cyclohexenone A with Nazarov substitute B in a double Michael addition to produce tricycle C. At the indicated position, C was reduced to the aldehyde and the alcohol group was protected with p-methoxybenzyl ether (PMB) to form the aldol precursor needed to produce D. After several steps, intermediate E was produced. E contained all the required functionalities and stereochemistry needed to produce ouabain. The structure of E was confirmed by comparison against the degradation product of ouabain. Methylation of E, catalyzed by rhodium, produced F. The dehydroxylation and selective oxidation of the secondary hydroxy group of F produced G. G reacted with triphenyl phosphoranylidene ketene and the ester bonds in G were hydrolyzed to produce ouabagenin, a precursor to ouabain. The glycosylation of ouabagenin with rhamnose produced ouabain.

History

Africa

Poisons derived from Acokanthera plants are known to have been used in Africa as far back as the 3rd century BC when Theophrastus reported a toxic substance that the Ethiopians would smear on their arrows.[5][21] The poisons derived from this genus of plants were used throughout eastern Africa, typically as arrow poisons for hunting and warfare. Acokanthera schimperi, in particular, exhibits a very large amount of ouabain, which the Kenyans, Tanzanians, Rwandans, Ethiopians, and Somalis would use as an arrow poison.[5]

The poison was extracted from the branches and leaves of the plant by boiling them over a fire. Arrows would then be dipped into the concentrated black tar-like juice that formed.[5] Often, certain magical additives were also mixed in with the ouabain extract in order to make the poison work according to the hunter's wishes. In Kenya, the Giriama and Langulu poison makers would add an elephant shrew to the poison mixture in order to facilitate the pursuit of their prey.[5] They had observed that an elephant shrew would always run straight ahead or follow a direct path and thought that these properties would be transferred to the poison. A poisonous arrow made with this shrew was thought to cause the hunted animal to behave like the shrew and run in a straight path. In Rwanda members of the Nyambo tribe, also known poison arrow makers, harvest the Aconkathera plants according to how many dead insects are found under it - more dead insects under a shrub indicating a higher potency of poison.[5]

Although ouabain was used as an arrow poison primarily for hunting, it was also used during battle. One example of this occurred during a battle against the Portuguese, who had stormed Mombasa in 1505. Portuguese records indicated that they had suffered a great deal from the poisoned arrows.[5]

Europe

European imperial expansion and exploration into Africa overlapped with the rise of the European pharmaceutical industry towards the end of the nineteenth century.[22] British troops were the target of arrows poisoned with the extracts of various Strophanthus species.[22] They were familiar with the deadly properties of these plants and brought samples back to Europe. Around this time, interest in the plant grew. It was known that ouabain was a cardiac poison, but there was some speculation about its potential medical uses.[5][22]

In 1882, ouabain was first isolated from the plant by the French chemist Léon-Albert Arnaud as an amorphous substance, which he identified as a glycoside.[5] Ouabain was seen as a possible treatment for certain cardiac conditions.

See also

References

- "ouabain" in the World English Dictionary

- "Ouabain C29H44O12". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Dobler S, Dalla S, Wagschal V, Agrawal AA (August 2012). "Community-wide convergent evolution in insect adaptation to toxic cardenolides by substitutions in the Na,K-ATPase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (32): 13040–13045. doi:10.1073/pnas.1202111109. PMC 3420205. PMID 22826239.

- "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF) (July 1, 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- Neuwinger HD (1996). African ethnobotany : poisons and drugs : chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology. Chapman & Hall. ISBN 3-8261-0077-8. OCLC 34675903.

- Yu SP, Choi DW (June 1997). "Na+–Ca2+ exchange currents in cortical neurons: concomitant forward and reverse operation and effect of glutamate". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 9 (6): 1273–1281. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01482.x. PMID 9215711. S2CID 23146698.

- Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP, Bova S, DuCharme DW, Harris DW, Mandel F, et al. (July 1991). "Identification and characterization of a ouabain-like compound from human plasma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 88 (14): 6259–6263. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.6259H. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.14.6259. PMC 52062. PMID 1648735. Erratum in: Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991 Nov 1; 88(21):9907

- Manunta P, Ferrandi M, Bianchi G, Hamlyn JM (January 2009). "Endogenous ouabain in cardiovascular function and disease". Journal of Hypertension. 27 (1): 9–18. doi:10.1097/hjh.0b013e32831cf2c6. PMID 19050443. S2CID 41618824.

- Hamlyn JM, Laredo J, Shah JR, Lu ZR, Hamilton BP (April 2003). "11-hydroxylation in the biosynthesis of endogenous ouabain: multiple implications". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 986 (1): 685–693. Bibcode:2003NYASA.986..685H. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07283.x. PMID 12763919. S2CID 23738926.

- Hamlyn JM, Blaustein MP (September 2016). "Endogenous Ouabain: Recent Advances and Controversies". Hypertension. 68 (3): 526–532. doi:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.06599. PMC 4982830. PMID 27456525.

- Lewis LK, Yandle TG, Hilton PJ, Jensen BP, Begg EJ, Nicholls MG (October 2014). "Endogenous ouabain is not ouabain". Hypertension. 64 (4): 680–683. doi:10.1161/hypertensionaha.114.03919. PMID 25001271.

- Malawista I, Davidson EA (December 1961). "Isolation and identification of rhamnose from rabbit skin". Nature. 192 (4805): 871–2. doi:10.1038/192871a0. PMID 14468825. S2CID 4285678.

- Staessen JA, Thijs L, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Bacchieri A, Barton J, Espositi ED, et al. (January 2011). "Main results of the ouabain and adducin for Specific Intervention on Sodium in Hypertension Trial (OASIS-HT): a randomized placebo-controlled phase-2 dose-finding study of rostafuroxin". Trials. 12: 13. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-13. PMC 3031200. PMID 21235787.

- Fürstenwerth H (November 2010). "Ouabain - the insulin of the heart". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 64 (12): 1591–1594. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02395.x. PMID 20946265. S2CID 6749622.

- Cowan T, MD, (2016) Human Heart, Cosmic Heart: A Doctor's Quest to Understand, Treat and Prevent Cardiovascular Disease, Chap 9, ISBN 9781603586191

- Welsh J (2011). "Giant rat kills predators with poisonous hair". LiveScience. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- Morelle R (2011). "African crested rat uses poison trick to foil predators". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- "Rat makes its own poison from toxic tree". University of Oxford. 2011. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- Zhang H, Sridhar Reddy M, Phoenix S, Deslongchamps P (2008). "Total synthesis of ouabagenin and ouabain". Angewandte Chemie (International ed. In English). 47 (7): 1272–1275. doi:10.1002/anie.200704959. PMID 18183567.

- Zhang H, Reddy MS, Phoenix S, Deslongchamps P (June 2008). "Synthesis of Ouabain". Synfacts. 6 (6): 0562. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1072606.

- Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Nelson L, Goldfrank LR, Flomenbaum N (2014-12-23). Goldfrank's toxicologic emergencies (Tenth ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-180184-3. OCLC 861895453.

- Osseo-Asare AD (August 2008). "Bioprospecting and Resistance: Transforming Poisoned Arrows into Strophantin Pills in Colonial Gold Coast, 1885-1922". Social History of Medicine. 21 (2): 269–290. doi:10.1093/shm/hkn066.

External links

- Dobler S, Dalla S, Wagschal V, Agrawal AA (August 2012). "Community-wide convergent evolution in insect adaptation to toxic cardenolides by substitutions in the Na,K-ATPase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (32): 13040–13045. doi:10.1073/pnas.1202111109. PMC 3420205. PMID 22826239.

- Hamlyn JM. "Ouabainomics". University of Maryland.

- Rudolf RD (October 1922). "The Use of Circulatory Stimulants in the Care of the Sick". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 12 (10): 697–701. PMC 1706809. PMID 20314209.

- Tanz RD (May 1964). "The Action of Ouabain on Cardiac Muscle Treated with Reserpine and Dichloroisoproterenol". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 144 (2): 205–213. PMID 14183432.