Caligula

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (/kəˈlɪɡjʊlə/), was Roman emperor from AD 37 until his assassination in AD 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Agrippina the Elder, Augustus' granddaughter. Caligula was born into the first ruling family of the Roman Empire, conventionally known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

| Caligula | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

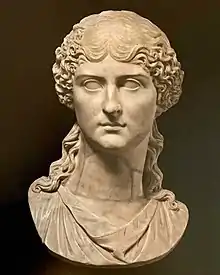

.jpg.webp) Marble bust, 37—41 CE | |||||

| Roman emperor | |||||

| Reign | 16 March 37 – 24 January 41 | ||||

| Predecessor | Tiberius | ||||

| Successor | Claudius | ||||

| Born | Gaius Julius Caesar 31 August AD 12 Antium, Italy | ||||

| Died | 24 January AD 41 (aged 28) Palatine Hill, Rome, Italy | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouses | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Julio-Claudian | ||||

| Father | Germanicus | ||||

| Mother | Agrippina | ||||

Although Gaius was named after Gaius Julius Caesar, he acquired the nickname "Caligula" ('little boot'), the diminutive form of caliga, a military boot, from his father's soldiers during their campaign in Germania. When Germanicus died at Antioch in 19, Agrippina returned with her six children to Rome, where she became entangled in a bitter feud with the emperor Tiberius (Germanicus' biological uncle and adoptive father). The conflict eventually led to the destruction of her family, with Caligula as the sole male survivor. In 26, Tiberius withdrew from public life to the island of Capri, and in 31, Caligula joined him there. Following the former's death in 37, Caligula succeeded him as emperor. There are few surviving sources about the reign of Caligula, though he is described as a noble and moderate emperor during the first six months of his rule. After this, the sources focus upon his cruelty, sadism, extravagance, and sexual perversion, presenting him as an insane tyrant.

While the reliability of these sources is questionable, it is known that during his brief reign, Caligula worked to increase the unconstrained personal power of the emperor, as opposed to countervailing powers within the principate. He directed much of his attention to ambitious construction projects and luxurious dwellings for himself, and he initiated the construction of two aqueducts in Rome: the Aqua Claudia and the Anio Novus. During his reign, the empire annexed the client kingdom of Mauretania as a province. In early 41, Caligula was assassinated as a result of a conspiracy by officers of the Praetorian Guard, senators, and courtiers. However, the conspirators' attempt to use the opportunity to restore the Roman Republic was thwarted. On the day of the assassination of Caligula, the Praetorians declared Caligula's uncle, Claudius, the next emperor. Caligula's death marked the official end of the Julii Caesares in the male line, though the Julio-Claudian dynasty continued to rule until the demise of his nephew, Nero.

Early life

Right: Marble portrait of Germanicus, Caligula's father

Caligula was born in Antium on 31 August AD 12, the third of six surviving children born to Germanicus and his wife and second cousin, Agrippina the Elder. Germanicus was a grandson of Mark Antony, and Agrippina was the daughter of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder, making her the granddaughter of Augustus.[2] The future emperor Claudius was Caligula's paternal uncle.[3] Caligula had two older brothers, Nero and Drusus, and three younger sisters, Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla and Julia Livilla.[2][4] At the age of two or three, he accompanied his father, Germanicus, on campaigns in the north of Germania.[5] He wore a miniature soldier's outfit, including army boots (caligae) and armour.[5] The soldiers thus nicknamed him Caligula ("little boot"). He reportedly grew to dislike the nickname.[6]

Germanicus died at Antioch, Syria, in AD 19, aged only 33. Suetonius claims that Germanicus was poisoned by an agent of Tiberius, who viewed Germanicus as a political rival.[7] After the death of his father, Caligula lived with his mother, Agrippina, until her relations with Tiberius deteriorated.[8] Tiberius would not allow Agrippina to remarry for fear her husband would be a rival.[9] Agrippina and Caligula's brother, Nero, were banished in the year 29 on charges of treason.[10][11] The adolescent Caligula was sent to live with his great-grandmother (Tiberius' mother), Livia. After her death, he was sent to live with his grandmother Antonia Minor.[8] In the year 30, his brother Drusus was imprisoned on charges of treason, and his brother Nero died in exile from either starvation or suicide.[11][12] Suetonius writes that after the banishment of his mother and brothers, Caligula and his sisters were nothing more than prisoners of Tiberius under the close watch of soldiers.[13] In the year 31, Caligula was remanded to the personal care of Tiberius at Villa Jovis on Capri, where he lived for six years.[8] To the surprise of many, Caligula was spared by Tiberius.[14] Roman historians describe Caligula as an excellent natural actor who recognized the danger he was in, and hid his resentment towards Tiberius. An observer said of Caligula, "Never was there a better servant or a worse master!"[8][15]

Caligula claimed to have planned to kill Tiberius with a dagger to avenge his mother and brother, however, having brought the weapon into Tiberius' bedroom he did not kill the Emperor but threw the dagger down on the floor. Supposedly Tiberius knew of this plot but did nothing about it.[16] Suetonius claims that Caligula was by this time already cruel and vicious; he writes that when Tiberius brought Caligula to the island of Capri, his purpose was to allow Caligula to live in order that he "prove the ruin of himself and of all men, and that he was rearing a viper for the Roman people and a Phaethon for the world."[17] In 33, Tiberius gave Caligula an honorary quaestorship, a position he held until his rise to emperor.[18] Meanwhile, both Caligula's mother and his brother Drusus died in prison.[19] Caligula was briefly married to Junia Claudilla in the year 33, though she died in childbirth the following year.[16] Caligula spent time befriending the Praetorian prefect, Naevius Sutorius Macro, an important ally.[16] Macro spoke well of Caligula to Tiberius, attempting to quell any ill will or suspicion the Emperor felt towards Caligula.[20] In the year 35, Caligula was named joint heir to Tiberius' estate along with Tiberius Gemellus.[21]

Emperor

Early reign

Tiberius died on 16 March AD 37, a day before the Liberalia festival. Rumors circulated that Caligula, possibly assisted by Macro, smothered Tiberius with a pillow,[22] recorded both by Suetonius and Tacitus.[16][23] However, Philo, who wrote during Tiberius' reign, and Josephus, who began his service to the Romans under Nero, both record Tiberius as having died a natural death.[24][25] Caligula assumed the leadership of the domus Caesaris and this was ratified by the senate, which acclaimed him imperator two days later on 18 March.[26] Ten days later, Tiberius' will, naming two heirs, was nullified with the standard justification that he had been insane.[22][27]

Caligula is described as the first emperor who was admired by everyone in "all the world, from the rising to the setting sun."[28] Caligula was loved by many for being the beloved son of the popular Germanicus[29] and because he was not Tiberius.[30] Suetonius said that over 160,000 animals were sacrificed during three months of public rejoicing to usher in the new reign.[31] Philo mentions widespread sacrifice, but no estimation on the degree. He describes the first seven months of Caligula's reign as completely blissful.[32]

Caligula's first acts were said to be generous in spirit, though many were political in nature.[27] Overriding Tiberius' will, which left a legacy of 500 sesterces to each praetorian, he instead doubled it;[33] further bonuses were granted to the city troops and the army outside Italy.[27] Coinage indicates that donations to the praetorians may have been repeated through Caligula's reign. A further distribution of 75 sesterces per citizen in Rome was given from 1 June to 19 July; Caligula wasted no time putting on lavish games, immediately requesting from the senate exemption from sumptuary laws limiting the number of gladiators. He also restored the right to elect praetors to the comitia, which meant in practice that aediles had incentives to spend money to put on lavish spectacles to win popularity. Building projects on the Palatine hill and elsewhere were also announced, which would have been the largest of these expenditures.[33]

Caligula also took action to win the support of the aristocracy. He made a public show of burning Tiberius' secret papers, falsely claiming that he had not read them. On coinage, he advertised that he had restored the rule of law; to that end, he lifted a backlog on court cases in Rome by adding more jurors and lifting the need for imperial confirmation of sentences.[34] Refusing the title pater patriae on the grounds of his youth, he also recalled those who had been sent into exile.[33][35] Stressing his descent from Augustus, he went in person to retrieve the remains of his mother and brothers for interment in the Mausoleum of Augustus.[36][37] His sisters and other family members, including Claudius – who had not been a member of the imperial household during Tiberius' reign – were granted political and priestly honours. Work on a temple to Livia, vowed but never constructed, also began.[38]

Those whom Tiberius alone had supported lost out. Gemellus was required to kill himself on charges of having taken an antidote, "ie implicitly accusing Caligula of wanting to poison him". Tiberius' political associate Marcus Junius Silanus, a support of Gemellus, was executed; Caligula's friend Macro also was killed. These purges suggest "the new emperor had learnt a great deal from Tiberius" and "that attempts to divide his reign into a 'good' beginning followed by unremitting atrocities... are misplaced".[36] This division into good and bad phases has variously been attributed to the death of Antonia in summer 37, illness in autumn that year, or the death of Caligula's beloved sister Drusilla on 10 June AD 38.[39]

During his illness in AD 37 and after Gemellus' death, Caligula named his brother-in-law, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus as heir, marrying him to his sister Drusilla. Ancient sources allege that he and Lepidus were homosexual lovers. After Drusilla's death in June AD 38, she was deified in September the same year.[40]

Public reform and financial crisis

In the year 38, Caligula focused his attention on political and public reform. He published the accounts of public funds, which had not been made public during the reign of Tiberius. He aided those who lost property in fires, abolished certain taxes, and gave out prizes to the public at gymnastic events. He allowed new members into the equestrian and senatorial orders.[41] Perhaps most significantly, he restored the practice of elections.[42] Cassius Dio said that this act "though delighting the rabble, grieved the sensible, who stopped to reflect, that if the offices should fall once more into the hands of the many... many disasters would result".[41] During the same year, though, Caligula was criticized for executing people without full trials and for forcing the Praetorian prefect, Macro, to commit suicide.[43]

According to Cassius Dio, a financial crisis emerged in 39.[43] Suetonius places the beginning of this crisis in 38.[44] Caligula's political payments for support, generosity and extravagance had exhausted the state's treasury. Ancient historians state that Caligula began falsely accusing, fining and even killing individuals for the purpose of seizing their estates.[45] Historians describe a number of Caligula's other desperate measures. To gain funds, Caligula asked the public to lend the state money.[46] He levied taxes on lawsuits, weddings and prostitution.[16] Caligula began auctioning the lives of the gladiators at shows.[45][47] Wills that left items to Tiberius were reinterpreted to leave the items instead to Caligula. Centurions who had acquired property by plunder were forced to turn over spoils to the state. The current and past highway commissioners were accused of incompetence and embezzlement and forced to repay money.[48]

According to Suetonius, in the first year of Caligula's reign he squandered 2.7 billion sesterces that Tiberius had amassed.[44] His nephew Nero both envied and admired the fact that Caligula had run through the vast wealth Tiberius had left him in so short a time.[49] However, some historians have shown scepticism towards the large number of sesterces quoted by Suetonius and Dio. According to Wilkinson, Caligula's use of precious metals to mint coins throughout his principate indicates that the treasury most likely never fell into bankruptcy. He does point out, however, that it is difficult to ascertain whether the purported 'squandered wealth' was from the treasury alone due to the blurring of "the division between the private wealth of the emperor and his income as head of state."[50] Furthermore, Alston points out that Caligula's successor, Claudius, was able to donate 15,000 sesterces to each member of the Praetorian Guard in 41,[23] suggesting the Roman treasury was solvent.[51] A brief famine of unknown extent occurred, perhaps caused by this financial crisis, but Suetonius claims it resulted from Caligula's seizure of public carriages;[45] according to Seneca, grain imports were disrupted because Caligula re-purposed grain boats for a pontoon bridge.[52]

Construction and senatorial feud

Despite financial difficulties, Caligula embarked on a number of construction projects during his reign. Some were for the public good, though others were for himself. Josephus describes Caligula's improvements to the harbours at Rhegium and Sicily, allowing increased grain imports from Egypt, as his greatest contributions.[54] These improvements may have been in response to the famine.[55] Caligula completed the temple of Augustus and the theatre of Pompey and began an amphitheatre beside the Saepta.[56] He also expanded the imperial palace.[57] Later, he began the construction of aqueducts Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus, which Pliny the Elder considered to be engineering marvels.[56][58][59] Caligula then built a large racetrack known as the circus of Gaius and Nero and had an Egyptian obelisk (now known as the "Vatican Obelisk") transported by sea and erected in the middle of Rome.[60] Construction of the aqueaduct Porta Maggiore started under his rule.

At Syracuse, he repaired the city walls and the temples of the gods.[56] He had new roads built and pushed to keep roads in good condition.[48][44] Caligula had planned to rebuild the palace of Polycrates at Samos, to finish the temple of Didymaean Apollo at Ephesus and to found a city high up in the Alps. He also intended to dig a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth in Greece and sent a chief centurion to survey the work.[56] In 39, Caligula performed a spectacular stunt by ordering a temporary floating bridge to be built using ships as pontoons, stretching for over two miles from the resort of Baiae to the neighbouring port of Puteoli.[61] It was said that the bridge was to rival the Persian king Xerxes' pontoon bridge crossing of the Hellespont.[62] Caligula, who could not swim,[11] then proceeded to ride his favourite horse Incitatus across, wearing the breastplate of Alexander the Great.[62] This act was in defiance of a prediction by Tiberius' soothsayer Thrasyllus of Mendes that Caligula had "no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding a horse across the Bay of Baiae".[62]

Caligula had two large ships constructed for himself (which were recovered from the bottom of Lake Nemi around 1930). The ships were among the largest vessels in the ancient world. The smaller ship was designed as a temple dedicated to Diana. The larger ship was essentially an elaborate floating palace with marble floors and plumbing.[63] The ships burned in 1944 after an American attack in the Second World War; almost nothing remains of their hulls, though many archaeological treasures remain intact in the museum at Lake Nemi and in the Museo Nazionale Romano (Palazzo Massimo) at Rome.[64]

In 39, relations between Caligula and the Roman Senate deteriorated.[65][66] The subject of their disagreement is unknown. A number of factors, though, aggravated this feud. The Senate had become accustomed to ruling without an emperor between the departure of Tiberius for Capri in 26 and Caligula's accession. Additionally, Tiberius' treason trials had eliminated a number of pro-Julian senators such as Asinius Gallus.[67] Caligula reviewed Tiberius' records of treason trials and decided, based on their actions during these trials, that numerous senators were not trustworthy. He ordered a new set of investigations and trials.[65][66] He replaced the consul and had several senators put to death. Suetonius reports that other senators were degraded by being forced to wait on him and run beside his chariot.[68] Soon after his break with the Senate, Caligula faced a number of additional conspiracies against him.[69] That autumn, he claimed to have uncovered a conspiracy to replace him with his then-heir Lepidus. Publicising the failure of the sitting consuls to offer prayers on his birthday – 31 August – he gave orders to concentrate military forces in upper Germany. The governor there, Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus was possibly a threat and after Caligula's personal arrival there, was executed. Lepidus, Agrippina, and Livilla, were accused to being part of this conspiracy: Lepidus was executed and the two sisters were exiled after being condemned pro forma of adultery.[70][69]

Western expansion

In 40, Caligula expanded the Roman Empire into Mauretania,[2] a client kingdom of Rome ruled by Ptolemy of Mauretania. Caligula invited Ptolemy to Rome and then suddenly had him executed.[71] Mauretania was annexed by Caligula and subsequently divided into two provinces, Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis, separated by the river Malua.[72] Pliny claims that division was the work of Caligula, but Dio states that in 42 an uprising took place, which was subdued by Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and Gnaeus Hosidius Geta, and the division only took place after this.[73] This confusion might mean that Caligula decided to divide the province, but the division was postponed because of the rebellion. The first known equestrian governor of the two provinces was Marcus Fadius Celer Flavianus, in office in 44.[74]

Details on the Mauretanian events of 39–44 are unclear. Cassius Dio wrote an entire chapter on the annexation of Mauretania by Caligula, but it is now lost.[75] Caligula's move seemingly had a strictly personal political motive – fear and jealousy of his cousin Ptolemy – and thus the expansion may not have been prompted by pressing military or economic needs.[76] However, the rebellion of Tacfarinas had shown how exposed Africa Proconsularis was to its west and how the Mauretanian client kings were unable to provide protection to the province, and it is thus possible that Caligula's expansion was a prudent response to potential future threats.[74]

Caligula brought up abortive attempts to extend Roman rule into Britannia.[2] Two legions had been raised for this purpose (both were likely named Primigeniae in honour of Caligula's newborn daughter). Ancient sources depict Caligula as being too cowardly to have attacked or as mad, but stories of his threatening decimation indicates mutinies. Broadly, "it is impossible to judge why the army never embarked" on the invasion. Beyond mutinies, it may have simply been that British chieftains acceded to Rome's demands, removing any justification for war.[77][75] Alternatively, it could have been merely a training and scouting mission[78] or a short expedition to accept the surrender of the British chieftain Adminius.[79][80] Suetonius reports that Caligula ordered his men to collect seashells as "spoils of the sea"; this may also be a mistranslation to musculi, meaning siege engines.[77][81] The conquest of Britannia was later achieved during the reign of his successor, Claudius.

Claims of divinity

When Tiberius died, hated by his subjects, Caligula dutifuly asked the Senate to approve his deification but was turned down, in line with senatorial and popular opinion. Caligula did not push the issue. He gave Tiberius a magnificent, long drawn out funeral at public expense, and a tearful eulogy.[82] In the first six months of his reign, he made a good impression, refusing costly honours such as statuary of himself, and apparently promising to share power with his senate, as primus inter pares ("first among equals"). His modesty and personal generosity earned him broad approval; but at some time early in his short reign, possibly following a near-mortal illness, this changed.

Philo, Caligula's contemporary, claims that Caligula costumed himself as various heroes and deities, starting with demigods such as Dionysos, Herakles and the Dioscuri, and working up to major deities such as Mercury, Venus and Apollo. Philo describes these alleged impersonations in a context of private pantomime or theatrical performances, as evidence that Caligula wanted to be a god himself.[83][84] Dio claims that Caligula impersonated Jupiter as no more than a means to seduce various women. Philo's list of impersonations does not include Jupiter at all. To Gradel, the same performances prove no more than Caligula's penchant for theatre, fancy-dress and desire to shock; as emperor, Caligula was also pontifex maximus, one of Rome's most powerful and influential state priests. While he seems to have been amused by baiting the elite who held Rome's most important priesthoods, he seems to have taken his own religious duties very seriously, reorganising the Salii (priests of Mars), and pedanticaly insisting that it was nefas (religiously improper) for Jupiter's leading priest, the Flamen Dialis, to swear the imperial oath of loyalty.[lower-alpha 1] Suetonius claims that Caligula found a replacement for the aging priest of Diana's ancient sanctuary at Lake Nemi. Traditionally, the priest must be slain by a runaway slave, who must then replace him; the "slaying" was almost certainly symbolic, not actual.[85] Caligula had two vast and exquisitely appointed ships built at Nemi; one a floating palace, for himself, and the other a "floating temple" for the goddess.[86]

Dio claims that Caligula sometimes referred to himself as a divinity in public meetings, and was sometimes referred to as "Jupiter" in public documents; Caligula's special interest in Jupiter, king of the gods, is confirmed by all surviving sources. Simpson believes that Caligula may have considered Jupiter an equal, perhaps a rival. [87][88][89] In Rome's eastern provinces, cults to rulers as divine and semi-divine saviours and monarchs were long-standing institutions; one of the best known examples is that of Alexander the Great, a divine monarch to at least some of his subjects, and whom Caligula also impersonated.[90] The promotion of mortals to godlike status, based on their superior standing and perceived merits, was also a well established feature of Roman culture; a client could flatter their living patron as "Jupiter on earth", without reprimand.[91] There is no evidence that Caligula intended to supplant Rome's most important deity and protector, Capitoline Jupiter.[92]

A temple to Caligula in the city of Rome is mentioned only by Suetonius and Dio. Augustus had already linked the Temple of Castor and Pollux directly to his imperial residence on the Palatine, and established an official priesthood of lesser magistrates to serve its cults, the seviri Augustales, usually promoted from his own freedmen to serve the genius Augusti (his "family spirit") and Lares (the twinned ancestral spirits of his household).[93]Dio claims that Caligula stationed himself, dressed as Jupiter Latiaris, as an object of worship between the images of Castor and Pollux, the twin Dioscuri, whom he humorously referred to as his doorkeepers.[94][95][96]

According to Cassius Dio, living emperors could be worshipped as divine in the east and dead emperors could be worshipped as divine in Rome.[97] An embassy from Greek states to Rome greeted Caligula as the "new god Augustus". In the Greek city of Cyzicus, a public inscription from the beginning of Caligula's reign gives thanks to him as a "New Sun-god".[98] Egyptian provincial coinage and some state dupondii show Caligula enthroned; the first reigning Roman princeps described as the "New Sun", (Neos Helios) with the radiate crown of the Sun-god, or of Caligula's divine antecedent, the divus Augustus. Caligula's image on other state coinage carries no such "trappings of divinity". [99] In Rome and elsewhere, cult to the genius (generative spirit) of living patrons and benefactors was a religious duty of their clients and inferiors. Compared to the full-blown cults to major deities of state, genius cults were quite modest in scope and religious paraphernalia, a feature of household religion which recognised the head of family's god-like superiority and virtues. Augustus, once deceased, was officially worshipped as a divus - an immortal, but somewhat less than a full-blown deity; Tiberius, his successor, forbade his own personal cult outright in Rome itself, probably in consideration of Julius Caesar's assassination following his hubristic promotion as a living divinity.[97]

Dio claims that two temples were built for Caligula in Rome:[94] but no confirmation has been found for this. Simpson believes it likely that Caligula was voted a temple on the Palatine by the Senate, but funded it himself.[100] Gradel sees Caligula's reported extortion of priesthood fees from an unwilling aristocracy, including his uncle Claudius, as a mark of private cult and personal humiliation among the elite. Throughout his reign, Caligula seems to have remained popular with the masses, in Rome and the empire. There is no sound evidence that he caused the removal, replacement or imposition of Roman or other deities, or even that he threatened to do so, outside the hostile anecdotes of his biographers. He seems to have taken his own genius cult very seriously; but as Gradel observes, no Roman was ever prosecuted for sacrificing to his emperor.[101] Caligula's fatal offense was to willfully "insult or offend everyone who mattered", including the military officers who assassinated him.[102][103] His cult died with him.

Eastern policy

Caligula needed to quell several riots and conspiracies in the eastern territories during his reign. Aiding him in his actions was his good friend, Herod Agrippa, who became governor of the territories of Batanaea and Trachonitis after Caligula became emperor in 37.[104][105] The cause of tensions in the east was complicated, involving the spread of Greek culture, Roman law and the rights of Jews in the empire. Caligula did not trust the prefect of Egypt, Aulus Avilius Flaccus. Flaccus had been loyal to Tiberius, had conspired against Caligula's mother and had connections with Egyptian separatists.[106] In 38, Caligula sent Agrippa to Alexandria unannounced to check on Flaccus.[107] According to Philo, the visit was met with jeers from the Greek population who saw Agrippa as the king of the Jews.[108] As a result, riots broke out in the city.[109] Caligula responded by removing Flaccus from his position and executing him.[110]

In 39, Agrippa accused his uncle Herod Antipas, the tetrarch of Galilee and Perea, of planning a rebellion against Roman rule with the help of Parthia. Herod Antipas confessed and Caligula exiled him. Agrippa was rewarded with his territories.[111] Riots again erupted in Alexandria in 40 between Jews and Greeks. Jews were accused of not honouring the emperor.[112] Disputes occurred in the city of Jamnia; Jews were angered by the erection of a clay altar and destroyed it.[113] In response, Caligula ordered the erection of a statue of himself in the Jewish Temple of Jerusalem,[114] a demand in conflict with Jewish monotheism. In this context, Philo wrote that Caligula "regarded the Jews with most especial suspicion, as if they were the only persons who cherished wishes opposed to his".[115]

The Governor of Syria, Publius Petronius, fearing civil war if the order were carried out, delayed implementing it for nearly a year.[116] Agrippa finally convinced Caligula to reverse the order.[112] However, Caligula issued a second order to have his statue erected in the Temple of Jerusalem. In Rome, another statue of himself, of colossal size, was made of gilt brass for the purpose. However, according to Josephus, when the ship carrying the statue was still underway, news of Caligula's death reached Petronius. Thus, the statue was never installed.[117]

Scandals

Philo and Seneca the Younger, contemporaries of Caligula, describe him as an insane emperor who was self-absorbed and short-tempered, who killed on a whim and indulged in too much spending and sex.[118][119][120] He is accused of sleeping with other men's wives and bragging about it,[121] killing for mere amusement,[118] deliberately wasting money on his bridge, causing starvation,[119] and wanting a statue of himself in the Temple of Jerusalem for his worship.[114] Once, at some games at which he was presiding, he was said to have ordered his guards to throw an entire section of the audience into the arena during the intermission to be eaten by the wild beasts because there were no prisoners to be used and he was bored.[43]

While repeating these earlier stories, the later sources of Suetonius and Cassius Dio provide additional tales of insanity. They accuse Caligula of incest with his sisters, Agrippina the Younger, Drusilla, and Livilla, and say that he prostituted them to other men.[122][69][123] Additionally, they mention affairs with various men including his brother-in-law Marcus Lepidus.[124][125] They say he sent troops on illogical military exercises,[75][126] turned the palace into a brothel,[46] and, most famously, planned or promised to make his horse, Incitatus, a consul,[127][128][47] and appointed a priest to serve him.[94] The validity of these accounts is debatable. In Roman political culture, insanity and sexual perversity were often presented hand-in-hand with poor government.[129]

Assassination and aftermath

Caligula's actions as emperor were described as being especially harsh to the Senate, to the nobility and to the equestrian order.[130] According to Josephus, these actions led to several failed conspiracies against Caligula.[131][132][133] Eventually, officers within the Praetorian Guard led by Cassius Chaerea succeeded in murdering the emperor.[134] The plot is described as having been planned by three men, but many in the Senate, army and equestrian order were said to have been informed of and involved in it.[135] The situation had escalated when, in the year 40, Caligula announced to the Senate that he planned to leave Rome permanently and to move to Alexandria in Egypt, where he hoped to be worshipped as a living god. The prospect of Rome losing its emperor and thus its political power was the final straw for many. Such a move would have left both the Senate and the Praetorian Guard powerless to stop Caligula's repression and debauchery. With this in mind Chaerea persuaded his fellow conspirators, who included Marcus Vinicius and Lucius Annius Vinicianus, to put their plot into action quickly.

According to Josephus, Chaerea had political motivations for the assassination.[136] Suetonius sees the motive in Caligula calling Chaerea derogatory names.[131] Caligula considered Chaerea effeminate because of a weak voice and for not being firm with tax collection.[137][138] Caligula would mock Chaerea with names like "Priapus" and "Venus".[137][131] On 24 January 41,[140] Cassius Chaerea and other guardsmen accosted Caligula as he addressed an acting troupe of young men beneath the palace during a series of games and dramatics being held for the Divine Augustus.[141] Details recorded on the events vary somewhat from source to source, but they agree that Chaerea stabbed Caligula first, followed by a number of conspirators.[137][141][142] Suetonius records that Caligula's death resembled that of Julius Caesar. He states that both the elder Gaius Julius Caesar (Julius Caesar) and the younger Gaius Julius Caesar (Caligula) were stabbed 30 times by conspirators led by a man named Cassius (Cassius Longinus and Cassius Chaerea respectively).[143] By the time Caligula's loyal Germanic guard responded, the Emperor was already dead. The Germanic guard killed several assassins and conspirators, along with some innocent senators and bystanders.[144][141] These wounded conspirators were treated by the physician Arcyon.

The cryptoporticus (underground corridor) beneath the imperial palaces on the Palatine Hill where this event took place was discovered by archaeologists in 2008.[145] The Senate attempted to use Caligula's death as an opportunity to restore the Republic.[146] Chaerea tried to persuade the military to support the Senate. The military, though, remained loyal to the idea of imperial monarchy.[147] Uncomfortable with lingering imperial support, the assassins sought out and killed Caligula's wife, Caesonia, and killed their young daughter, Julia Drusilla, by smashing her head against a wall.[148] They were unable to reach Caligula's uncle, Claudius. A soldier, Gratus, found Claudius hiding behind a palace curtain; he was spirited out of the city by a sympathetic faction of the Praetorian Guard to their nearby camp.[149] Claudius became emperor after procuring the support of the Praetorian Guard. Claudius granted a general amnesty, although he executed a few junior officers involved in the conspiracy, including Chaerea.[150][151][152] According to Suetonius, Caligula's body was placed under turf until it was burned and entombed by his sisters. He was buried within the Mausoleum of Augustus; in 410, during the Sack of Rome, the ashes in the tomb were scattered.

Legacy

Contemporary historiography

The facts and circumstances of Caligula's reign are mostly lost to history. Two major literary sources contemporary with Caligula have survived – the works of Philo and Seneca the Younger. Philo's works, On the Embassy to Gaius and Flaccus, give some details on Caligula's early reign, but mostly focus on events surrounding the Jewish population in Judea and Egypt with whom he sympathizes. Seneca's various works give mostly scattered anecdotes on Caligula's personality. Seneca was almost put to death by Caligula in AD 39 probably due to his associations with conspirators.[153] At one time, there were detailed contemporaneous histories on Caligula, but they are now lost. Additionally, the historians who wrote them are described as biased, either overly critical or praising Caligula.[154] Nonetheless, these lost primary sources, along with the works of Seneca and Philo, were the basis of surviving secondary and tertiary histories on Caligula written by the next generations of historians. A few of the contemporaneous historians are known by name. Fabius Rusticus and Cluvius Rufus both wrote condemning histories on Caligula that are now lost. Fabius Rusticus was a friend of Seneca who was known for historical embellishment and misrepresentation.[155] Cluvius Rufus was a senator involved in the assassination of Caligula.[156]

Caligula's sister, Agrippina the Younger, wrote an autobiography that certainly included a detailed explanation of Caligula's reign, but it too is lost. Agrippina was banished by Caligula for her connection to Marcus Lepidus, who conspired against him.[69] The inheritance of Nero, Agrippina's son and the future emperor, was seized by Caligula. Gaetulicus, a poet, produced a number of flattering writings about Caligula, but they are lost. The bulk of what is known of Caligula comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio. Suetonius wrote his history on Caligula 80 years after his death, while Cassius Dio wrote his history over 180 years after Caligula's death. Cassius Dio's work is invaluable because it alone gives a loose chronology of Caligula's reign. A handful of other sources add a limited perspective on Caligula. Josephus gives a detailed description of Caligula's assassination. Tacitus provides some information on Caligula's life under Tiberius. In a now lost portion of his Annals, Tacitus gave a detailed history of Caligula. Pliny the Elder's Natural History has a few brief references to Caligula. There are few surviving sources on Caligula and none of them paints Caligula in a favourable light. The paucity of sources has resulted in significant gaps in modern knowledge of the reign of Caligula. Little is written on the first two years of Caligula's reign. Additionally, there are only limited details on later significant events, such as the annexation of Mauretania, Caligula's military actions in Britannia, and his feud with the Roman Senate. According to legend, during his military actions in Britannia, Caligula grew addicted to a steady diet of European sea eels, which led to their Latin name being Coluber caligulensis.[157]

Health

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Several contemporary and near-contemporary Roman sources describe Caligula as insane. It is notoriously difficult to distinguish fact from fiction among the many allegations of his aberrant behaviour as emperor. Several modern sources suggest various possible medical explanations, including encephalitis, epilepsy or meningitis, acquired during the illness early in his reign.[158] Philo, Josephus and Seneca see Caligula's "insanity" as a personality trait acquired through self-indulgence and the unlimited exercise of power.[111][159][160] Seneca states that Caligula became arrogant, angry and insulting once he became emperor.[161] According to Josephus, the power Caligula was able to exercise led him to think himself a living God.[111] Philo claims that Caligula became ruthless after nearly dying of an illness in the eighth month of his reign (in 37).[162]

Suetonius said that Caligula had "falling sickness", or epilepsy, when he was young.[163][164] He may have lived in daily fear of seizures.[165] In Romano-Greek medical theory, the most severe epilepsy attacks were associated with the full moon and the moon goddess Selene, with whom Caligula was claimed to converse and to enjoy sexual congress.[166][57][167]

Suetonius described Caligula as the following: "He was very tall and extremely pale, with an unshapely body, but very thin neck and legs. His eyes and temples were hollow, his forehead broad and grim, his hair thin and entirely gone on the top of his head, though his body was hairy... He was sound neither of body nor mind. As a boy he was troubled with the falling sickness, and while in his youth he had some endurance, yet at times because of sudden faintness he was hardly able to walk, to stand up, to collect his thoughts, or to hold up his head".[164] Based on scientific reconstructions of his official painted busts, Caligula had brown hair, brown eyes, and fair skin.[168] Some modern historians think that Caligula had hyperthyroidism.[169] This diagnosis is mainly attributed to Caligula's irritability and his "stare" as described by Pliny the Elder.

Cultural depictions

In film and series

- Welsh actor Emlyn Williams was cast as Caligula in the never-completed 1937 film I, Claudius.[170]

- He was played by Ralph Bates in the 1968 ITV historical drama series, The Caesars.[171]

- American actor Jay Robinson famously portrayed a sinister and scene-stealing Caligula in two epic films of the 1950s, The Robe (1953) and its sequel Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954).[172]

- He was played by John Hurt in the 1976 BBC mini-series I, Claudius.[173]

- A feature-length historical film Caligula was completed in 1979 with Malcolm McDowell in the lead role.

- He was portrayed by David Brandon in the 1982 historical exploitation film Caligula... The Untold Story.[174]

- Caligula is a character in the 2015 NBC series A.D. The Bible Continues and is played by British actor Andrew Gower. His portrayal emphasises Caligula's "debauched and dangerous" persona [175] as well as his sexual appetite, quick temper, and violent nature.

- The third season of the Roman Empire series (released on Netflix in 2019) is named Caligula: The Mad Emperor with South African actor Ido Drent in the leading role.[176]

- In the award-winning BBC show Horrible Histories he is portrayed by Simon Farnaby.

In literature and theatre

- Kajus Cezar Caligula, by Polish author Karol Hubert Rostworowski, is a play premiered in Juliusz Słowacki City Theater, Cracow, 31 March 1917. The title character is presented as a weak and unhappy man who became a victim of circumstances that brought him to power that surpassed him.

- Caligula, by French author Albert Camus, is a play in which Caligula returns after deserting the palace for three days and three nights following the death of his beloved sister, Drusilla. The young emperor then uses his unfettered power to "bring the impossible into the realm of the likely".[177]

- In the 1934 novel I, Claudius by English writer Robert Graves, Caligula is presented as a murderous sociopath who became clinically insane early in his reign. In the novel, at the age of only ten, Caligula drove his father Germanicus to a state of despair and death by secretly terrorizing him. Graves' Caligula commits incest with all three of his sisters and is implied to have murdered Drusilla. The novel was adapted for television in the 1976 BBC mini-series of the same name.

- The life of Incitatus, Caesar's favorite horse, is the subject of Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert's poem Kaligula (in Pan Cogito, 1974), and his political career.[178]

- A deified Caligula is the antagonist of the 2018 The Trials of Apollo novel The Burning Maze by Rick Riordan. He is presented as an insane tyrant who has returned from the dead - along with Commodus and Emperor Nero - to try to take over the modern world. His horse, Incitatus, also appears.

In opera

- A young Caligula appears as one of the characters in Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber's opera Arminio.

- Caligula is the main character in Detlev Glanert's opera Caligula, based on the Albert Camus play.

- Different composers from the Baroque era appear to have composed operatic works about Caligula, but most of these have been lost.

Notes

- Jupiter was the highest divine witness to oaths. The Flamen Dialis was sworn to his service, and was hedged about with an exhaustive range of prohibitions.

References

- Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 489. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- Suetonius, Caligula 7.

- Cassius Dio, Book LIX.6.

- Wood, Susan (1995). "Diva Drusilla Panthea and the Sisters of Caligula". American Journal of Archaeology. 99 (3): 457–482. doi:10.2307/506945. JSTOR 506945. S2CID 191386576.

- Suetonius, Caligula 9.

- Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of the Wise Man XVIII 2–5. See also Malloch (2009), Gaius and the nobiles, Athenaeum.

- Suetonius, Caligula 2.

- Suetonius, Caligula 10.

- Tacitus, IV.52.

- Tacitus, V.3.

- Suetonius, Caligula 54.

- Tacitus, V.10.

- Suetonius, Caligula 64.

- Suetonius, Caligula 62.

- Tacitus, VI.20.

- Suetonius, Caligula 12.

- Suetonius, Caligula 11.

- Cassius Dio, LVII.23.

- Tacitus, VI.23-25.

- Philo, On the Embassy VI.35.

- Suetonius, Caligula 76.

- Wiedemann 1996, p. 221.

- Tacitus, XII.53.

- Philo, On the Embassy IV.25.

- Josephus, XIII.6.9.

- Henzen, Wilhelm, ed. (1874). Acta Fratrum Arvalium. p. 63.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.1.

- Philo, On the Embassy II.10.

- Suetonius, Caligula 13.

- Suetonius, Tiberius 75.

- Suetonius, Caligula 14.

- Philo, On the Embassy II.12–13..

- Wiedemann 1996, p. 222.

- Wiedemann 1996, pp. 222–23.

- Suetonius, Caligula 15.

- Wiedemann 1996, p. 223.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.3.

- Wiedemann 1996, p. 223. Claudius was made Caligula's consular colleague in the new emperor's first consulship.

- Wiedemann 1996, p. 223. "It is useless to date the turning-point to before the death of Antonia (two months after his accession), an illness in the autumn... which is supposed to have affected his brain, or the death of his sister Drusilla".

- Wiedemann 1996, pp. 224–25.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.9–10.

- Suetonius, Caligula 16,2.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.10.

- Suetonius, Caligula 37.

- Suetonius, Caligula 38.

- Suetonius, Caligula 41.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.14.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.15.

- Suetonius, Nero 30.

- Wilkinson 2004, p. 10.

- Alston, Richard (2002). Aspects of Roman history, AD 14–117. London: Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-203-01187-4.

- Seneca the Younger, On the Shortness of Life XVIII.5.

- The Galleys of Lake Nemi. Scientific American Volume 95 Number 02 (July 1906). 14 July 1906. pp. 25–26.

- Josephus, XIX.2.5.

- "7.4: The Julio-Claudian Emperors". Chemistry LibreTexts. 8 August 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- Suetonius, Caligula 21.

- Suetonius, Caligula 22.

- Suetonius, Claudius 20.

- Pliny the Elder, XXXVI,122.

- Pliny the Elder, XVI.76.

- Wardle, David (2007). "Caligula's Bridge of Boats – AD 39 or 40?". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 56 (1): 118–120. JSTOR 25598379.

- Suetonius, Caligula 19.

- Kroos, Kenneth A. (2011). "Central Heating for Caligula's Pleasure Ship". The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology. 81 (2): 291–299. doi:10.1179/175812111X13033852943471. ISSN 1758-1206. S2CID 110624972.

- Carlson, Deborah N. (May 2002). "Caligula's Floating Palaces" (PDF). Archaeology. 55 (3): 26–31. JSTOR 41779576.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.16.

- Suetonius, Caligula 30.

- Tacitus, IV.41.

- Suetonius, Caligula 26.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.22.

- Wiedemann 1996, pp. 226–27.

- Suetonius, Caligula 35.

- Pliny the Elder, V.2.

- Cassius Dio, LX.8.

- Barrett 1989, p. 118.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.25.

- Sigman, Marlene C. (1977). "The Romans and the Indigenous Tribes of Mauritania Tingitana". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 26 (4): 415–439. JSTOR 4435574.

- Wiedemann 1996, p. 228.

- Bicknell, Peter (1968). "The emperor Gaius' military activities in AD 40". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 17 (4): 496–505. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4435047.

- Davies, R (1966). "The 'abortive invasion' of Britain by Gaius". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 15 (1): 124–128. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4434915.

- Malloch, SJV (2001). "Gaius on the Channel coast". Classical Quarterly. 51 (2): 551–556. doi:10.1093/cq/51.2.551. ISSN 1471-6844.

- Suetonius, Caligula 45–47.

- Bennett, 2006. p. 59

- Philo, On the Embassy XI–XV.

- Pollini, 2012, p. 377

- Barrett, 2007, p.145

- Carlson, Deborah N. (May 2002). "Caligula's Floating Palaces" (PDF). Archaeology. 55 (3): 26–31. JSTOR 41779576.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.26,28.

- Pollini, pp. 378-379

- Simpson, C. J. “The Cult of the Emperor Gaius.” Latomus, vol. 40, no. 3, 1981, pp. 495–496. JSTOR, Accessed 18 Sept. 2023.

- Barrett, 2006, p. 146

- Gradel, p.46, citing Plautus

- Simpson, C. J. “The Cult of the Emperor Gaius.” Latomus, vol. 40, no. 3, 1981, p. 503. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41532141. Accessed 18 Sept. 2023.

- Lott, John. B., The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 107-117, 172. ISBN 0-521-82827-9

- Cassius Dio, LIX.28.

- Barrett, 2006, pp.147-148

- Beard, M., Price, S., North, J., Religions of Rome: Volume 1, a History, illustrated, Cambridge University Press, 1998, pp.209-210. ISBN 0-521-31682-0

- Cassius Dio, LI.20.

- Barrett, 2006, p.143

- Pollini, John (2012). From Republic to Empire. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-8061-8816-4.

- Simpson, pp.506-507

- Gradel, Ittai, Emperor Worship and Roman Religion, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 263-268ISBN 0-19-815275-2

- Gradel, Ittai, Emperor Worship and Roman Religion, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 142-158 ISBN 0-19-815275-2

- Cassius Dio, LIX.26–28.

- Josephus, XVIII.6.10.

- Philo, Flaccus V.25.

- Philo, Flaccus III.8, IV.21.

- Philo, Flaccus V.26–28.

- Philo, Flaccus VI.43.

- Philo, Flaccus VII.45.

- Philo, Flaccus XXI.185.

- Josephus, XVIII.7.2.

- Josephus, XVIII.8.1.

- Philo, On the Embassy XXX.201.

- Philo, On the Embassy XXX.203.

- Philo, On the Embassy XVI.115.

- Philo, On the Embassy XXXI.213.

- Josephus, XVIII.8.

- Seneca the Younger, On Anger III.xviii.1.

- Seneca the Younger, On the shortness of life XVIII.5.

- Philo, On the Embassy XXIX.

- Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.1.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.11.

- Suetonius, Caligula 24.

- Suetonius, Caligula 36.

- "Cassius Dio – Book 59". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- Suetonius, Caligula 46–47.

- Woods, David (2014). "Caligula, Incitatus, and the Consulship". The Classical Quarterly. 64 (2): 772–777. doi:10.1017/S0009838814000470. ISSN 0009-8388. S2CID 170216093.

- Suetonius, Caligula 55.

- Younger, John G. (2004). Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. xvi. ISBN 978-0-415-24252-3.

- Josephus, XIX.1.1.

- Suetonius, Caligula 56.

- Tacitus, 16.17.

- Josephus, XIX.1.2.

- Josephus, XIX.1.3.

- Josephus, XIX.1.10, 1.14].

- Josephus, XIX.1.6.

- Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2.

- Josephus, XIX.1.5.

- Wardle, David (1991). "When did Gaius Caligula die?" Acta Classica 34 (1991): 158–165.

- Suetonius 58: "On the ninth day before the Kalends of February... Ruled three years, ten months and eight days"; Cassius Dio LIX.30: "Thus Gaius, after doing in three years, nine months, and twenty-eight days all that has been related, learned by actual experience that he was not a god." (this seems to give 23 January, but Dio is probably using exclusive reckoning, which does give 24).[139]

- Suetonius, Caligula 58.

- Josephus, XIX.1.14.

- Suetonius, Caligula 57–58.

- Josephus, XIX.1.15.

- Owen, Richard (17 October 2008). "Archaeologists unearth place where Emperor Caligula met his end". The Times. The Times, London. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- Josephus, XIX.2.

- Josephus, XIX.4.4.

- Suetonius, Caligula 59.

- Josephus, XIX.2.1.

- Suetonius, Claudius 11.

- Josephus, XIX 268–269.

- Cassius Dio, LX.3,4.

- Cassius Dio, LIX.19.

- Tacitus, I.1.

- Tacitus, Life of Julius Agricola X, Annals XIII.20.

- Josephus, XIX.1.13.

- Aemilius Macer, Theriaca 1.29.

- Sidwell, Barbara (2010). "Gaius Caligula's Mental Illness". Classical World. 103 (2): 183–206. doi:10.1353/clw.0.0165. ISSN 1558-9234. PMID 20213971. S2CID 39205847.

- Philo, On the Embassy XIII.

- Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.1; On Anger I.xx.8.

- Seneca the Younger, On Firmness XVII–XVIII; On Anger I.xx.8.

- Philo, On the Embassy II–IV.

- Benediktson, D. Thomas (1989). "Caligula's Madness: Madness or Interictal Temporal Lobe Epilepsy?". The Classical World. 82 (5): 370–375. doi:10.2307/4350416. JSTOR 4350416.

- Suetonius, Caligula 50.

- Benediktson, D. Thomas (1991). "Caligula's Phobias and Philias: Fear of Seizure?". The Classical Journal. 87 (2): 159–163. ISSN 0009-8353. JSTOR 3297970.

- Benediktson, D. Thomas. "Caligula's Phobias and Philias: Fear of Seizure?" The Classical Journal 87, no. 2 (1991): 159–161 http://www.jstor.org/stable/3297970

- Oswei Temkin (1971), The Falling Sickness (2nd ed.) pp. 3–4, 7, 13, 16, 26, 86, 92–96, 179.

- "The True Colours Of Greek and Roman Statues By Archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann". 24 January 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Katz, Robert S. (1972). "The Illness of Caligula". The Classical World. 65 (7): 223–2258. doi:10.2307/4347670. JSTOR 4347670. PMID 11619647.; refuted in Morgan, M. Gwyn (1973). "Caligula's Illness Again". The Classical World. 66 (6): 327–329. doi:10.2307/4347839. JSTOR 4347839.

- Yablonsky, Linda (26 February 2006). "'Caligula' Gives a Toga Party (but No One's Really Invited)". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- The Caesars at IMDb

- Robinson, Jay (1979). The Comeback. Word Books. ISBN 978-0-912376-45-5

- I, Claudius at IMDb

- Palmerini, Luca M.; Mistretta, Gaetano (1996). "Spaghetti Nightmares". Fantasma Books. p. 111.ISBN 0-9634982-7-4.

- Watch A.D. The Bible Continues Episodes at NBC.com, retrieved 9 May 2020

- Nolan, Emma (26 March 2019). "Roman Empire Caligula The Mad Emperor Netflix release date, cast, trailer, plot". Express.co.uk. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Sheaffer-Jones, Caroline (2012). "A Deconstructive Reading of Albert Camus' Caligula". Australian Journal of French Studies. 49 (1): 31–42. doi:10.3828/AJFS.2012.3. ISSN 0004-9468.

- English translation of "Caligula Speaks" Archived 2016-11-01 at the Wayback Machine, by Zbigniew Herbert, translated by Oriana Ivy

Bibliography

Modern sources

- Barrett, Anthony A. (1989). Caligula: the corruption of power. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5487-1.

- Wiedemann, T.E.J. (1996). "Tiberius to Nero". In Bowman, Alan K; et al. (eds.). The Augustan Empire, 43 BC–AD 69. Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 10 (2nd ed.). pp. 198–255. ISBN 0-521-26430-8.

- Wilkinson, Sam (2004). Caligula. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-24693-9.

Ancient sources

- Philo (1855) [c. 38 AD]. Various works. Translated by Charles Duke Yonge. Loeb Classical Library.

- Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (1932) [1st century]. Essays. Translated by Aubrey Stewart. Loeb Classical Library.

- Gaius Plinius Secundus (1961) [c. 77 AD]. Natural History. Translated by H. Rackham; W.H.S. Jones; D.E. Eichholz. Harvard University Press.

- Josephus (1737) [c. 96 AD]. "Chapters XVIII–XIX". Antiquities of the Jews. Translated by William Whiston. Harvard University Press.

- Publius Cornelius Tacitus (1924) [c. 110 AD]. The Annals. Translated by Frederick W. Shipley. Loeb Classical Library.

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (1914) [c. 121 AD]. "Life of Caligula". The Twelve Caesars. Translated by John Carew Rolfe. Loeb Classical Library.

- Lucius Cassius Dio (1927) [c. 230]. "Book 59". Roman History. Translated by Earnest Cary. Loeb Classical Library.

Further reading

- Balsdon, JPVD; et al. (2012). "Gaius (1), 'Caligula', Roman emperor, 12–41 CE". In Hornblower, Simon; et al. (eds.). The Oxford classical dictionary (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.2772. ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8. OCLC 959667246.

- Barrett, Anthony A.; Yardley, John C. (2023). The Emperor Caligula in the ancient sources. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198854579.

- Winterling, Aloys (2011). Caligula: a biography. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94314-8.

- Balsdon, V. D. (1934). The Emperor Gaius. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hurley, Donna W. (1993). An Historical and Historiographical Commentary on Suetonius' Life of C. Caligula. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

- Sandison, A. T. (1958). "The Madness of the Emperor Caligula". Medical History. 2 (3): 202–209. doi:10.1017/s0025727300023759. PMC 1034394. PMID 13577116.

- Wilcox, Amanda (2008). "Nature's Monster: Caligula as exemplum in Seneca's Dialogues". In Sluiter, Ineke; Rosen, Ralph M. (eds.). Kakos: Badness and Anti-value in Classical Antiquity. Mnemosyne Supplements. Vol. 307. Leiden: Brill.

.jpg.webp)