Garamond

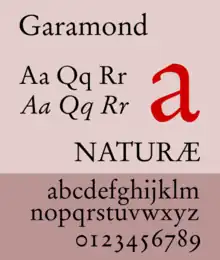

Garamond is a group of many serif typefaces, named for sixteenth-century Parisian engraver Claude Garamond, generally spelled as Garamont in his lifetime. Garamond-style typefaces are popular and particularly often used for book printing and body text.

| |

| Category | Serif |

|---|---|

| Classification | Old-style |

| Designer(s) | Claude Garamond Also: Robert Granjon Jean Jannon |

| Shown here | Adobe Garamond Pro (regular style based on Garamond's work; italic on the work of Robert Granjon) |

Garamond's types followed the model of an influential typeface cut for Venetian printer Aldus Manutius by his punchcutter Francesco Griffo in 1495, and are in what is now called the old-style of serif letter design, letters with a relatively organic structure resembling handwriting with a pen, but with a slightly more structured, upright design.

Following an eclipse in popularity in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, many modern revival faces in the Garamond style have been developed. It is common to pair these with italics based on those created by his contemporary Robert Granjon, who was well known for his proficiency in this genre.[1] However, although Garamond himself remains considered a major figure in French printing of the sixteenth century, historical research has increasingly placed him in context as one artisan punchcutter among many active at a time of rapid production of new typefaces in sixteenth-century France, and research has only slowly developed into which fonts were cut by him and which by contemporaries; Robert Bringhurst commented that "it was a widespread custom for many years to attribute almost any good sixteenth-century French font" to Garamond.[2][3][4] As a result, while "Garamond" is a common term in the printing industry, the terms "French Renaissance antiqua" and "Garalde" have been used in academic writing to refer generally to fonts on the Aldus-French Renaissance model by Garamond and others.[5][6]

In particular, many 'Garamond' revivals of the early twentieth century are actually based on the work of a later punchcutter, Jean Jannon, whose noticeably different work was for some years misattributed to Garamond. The most common digital font named Garamond is Monotype Garamond. Developed in the early 1920s and bundled with Microsoft Office, it is a revival of Jannon's work.

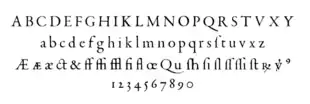

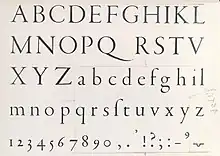

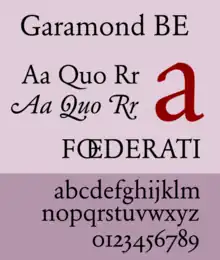

Characteristics

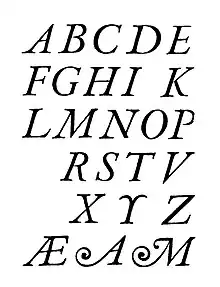

Some distinctive characteristics in Garamond's letterforms are an 'e' with a small eye and the bowl of the 'a' which has a sharp turn at top left.[8] Other general features are limited but clear stroke contrast and capital letters on the model of Roman square capitals. The 'M' is slightly splayed with outward-facing serifs at the top (sometimes only on the left) and the leg of the 'R' extends outwards from the letter. The x-height (height of lower-case letters) is low, especially at larger sizes, making the capitals large relative to the lower case, while the top serifs on the ascenders of letters like 'd' have a downward slope and ride above the cap height.[8] The axis of letters like the ‘o’ is diagonal and the bottom right of the italic 'h' bends inwards.[9] Garamond types have quite expansive ascenders and descenders; printers at the time did not use leading.[10][11][12]

Besides general characteristics, writers on type have generally praised the even quality of Garamond's type: John A. Lane describes his work as "elegant and executed with consummate skill...to a higher standard than commercial interest demanded";[13] H. D. L. Vervliet wrote that in his later Gros-Canon and Parangonne types (meaning sizes of around 40pt and 18pt respectively) he had achieved "a culmination of Renaissance design. The elegant line and subdued emphasis show the classic search for silent and transparent form".[14][lower-alpha 1]

Modern Garamond revivals also often add a matching bold and 'lining' numbers at the height of capital letters, neither of which were used during the Renaissance;[15] Arabic numerals in Garamond's time were engraved as what are now called text figures, styled with variable height like lower-case letters.[16]

History

Garamond’s life and his roman type

Garamond worked as an engraver of punches, the masters used to stamp matrices, the moulds used to cast metal type.[lower-alpha 2] Garamond cut types in the 'roman', or upright style, in italic, and Greek.[lower-alpha 3] In the period of Garamond's early life roman type had been displacing the blackletter or Gothic type which was used in some (although not all) early French printing.[20][21][22] Though his name was generally written as 'Garamont' in his lifetime, the spelling 'Garamond' became the most commonly used form after his death.[23][24] H. D. L. Vervliet, the leading contemporary expert on French Renaissance printing, uses Garamont consistently.[24]

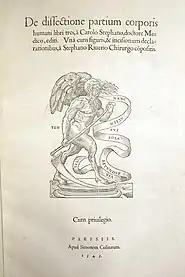

The roman designs of Garamond which are his most imitated were based on a font cut around 1495 for the Venetian printer Aldus Manutius by engraver Francesco Griffo.[25][26] This was first used in the book De Aetna, a short work by poet and cleric Pietro Bembo which was Manutius' first printing in the Latin alphabet.[27] Historian Beatrice Warde has assessed De Aetna as something of a pilot project, a small book printed to a higher standard than Manutius' norm.[28][29] Among other details, this font popularised the idea that in printing the cross-stroke of the 'e' should be level instead of slanting upwards to the right like handwriting, something imitated in almost all type designs since.[24][25] French typefounders of the 16th century assiduously examined Manutius's work (and, it is thought, De Aetna in particular)[27] as a source of inspiration: Garamond's roman, italic and greek typefaces were all influenced by types used by Manutius.[30]

An event which was to particularly define the course of the rest of Garamond's career came starting on 6 September 1530, when the printer Robert Estienne began to introduce a set of three[lower-alpha 4] roman types adapting the single roman type used in De Aetna to a range of sizes.[31][32] These typefaces, with their "light colour and precise cut"[33] were extremely influential and other Parisian printers immediately introduced copies.[34] The largest size "Gros-canon" (42.5pt)[lower-alpha 5] particularly became a "phenomenon"[36] in Paris: never before had a roman type been cut in so large a size.[37] The designs copied Manutius's type even to the extent of copying the 'M' shown in De Aetna which, whether intentionally or due to a casting defect, had no serif pointing out of the letter at top right.[38][39][40] This form was to appear in many fonts of the period, including Garamond's earlier ones, although by the end of his career he had switched to mostly using an M on the Roman capital model with a serif at top right.[41]

The period from 1520 to around 1560, encompassing Garamond's career, was an extremely busy period for typeface creation.[42] Many fonts were cut, some such as Robert Estienne's for a single printer's exclusive use, others sold or traded between them (increasingly over time).[43] The many active engravers included Garamond himself, Granjon, Guillaume Le Bé, particularly respected for his Hebrew fonts,[44][45] Pierre Haultin, Antoine Augereau (who may have been Garamond's master),[46] Estienne's stepfather Simon de Colines and others.[47] This period saw the creation of a pool of high-quality punches and matrices, many of which would remain used for the next two centuries.[48]

Little is known about Garamond's life or work before 1540, although he wrote in a preface of having cut punches for type since childhood.[46][49] He worked for a variety of employers on commission, creating punches and selling matrices to publishers and the government.[50] Garamond's typefaces were popular abroad, and replaced Griffo's original roman type at the Aldine Press in Venice.[30][51] He also worked as a publisher and bookseller.[49][52][53] By 1549, a document from theologian Jean de Gagny specified that the goldsmith Charles Chiffin, who had cut an italic for his private printing press, should receive payment at the rate of "the best punchcutter in this city after master Claude Garamont", clearly showing that he was considered the pre-eminent punchcutter in Paris at this time.[38]

Vervliet concludes that Garamond created thirty-four typefaces for which an attribution can be confidently made (17 roman, 7 italic, 8 Greek, 2 Hebrew) and another three for which the attribution is problematic (one each of roman, Greek and Hebrew).[54] If Garamond distributed specimens of his typefaces, as later punchcutters and typefounders did, none is known to survive, although one unsigned specimen in the Plantin-Moretus Museum collection, presenting a synopsis of his late Parangon type, may have been made around the time of his death or soon after.[lower-alpha 6]

While some records such as Christophe Plantin's exist of what exact types were cut by Garamond himself, many details of his career remain uncertain: early estimates placed Garamond's date of birth around 1480, but modern opinion proposes much later estimates.[24] A document called the Le Bé Memorandum (based on the memories of Guillaume Le Bé, but collated by one of his sons around 1643) suggests that Garamond finished his apprenticeship around 1510.[56][57] This is considered unlikely by modern historians since his mother was still alive when he died in 1561 and little is known of him before around 1540.[24][49][58]

One particular question about Garamond's early career is whether he cut the typefaces used by Estienne from 1530. Because of Garamond's known connection with Estienne in his later career, it has been assumed that he cut them,[27] but this was not mentioned in contemporary sources: Vervliet suggests that these 'Estienne typefaces' were not cut by Garamond and that his career began somewhat later.[59][60][61][62] Vervliet suggests that the creator of this set of typefaces, sometimes called the 'Estienne Master', may have been a 'Master Constantin', recorded in the Le Bé Memorandum as a master type engraver of the period before Garamond but about whom nothing is otherwise known and to whom no obvious other body of work can be ascribed.[63][lower-alpha 7] If so, his disappearance from history (perhaps due to an early death, since all his presumed work appeared in just four years from 1530 to 1533) and the execution of Augereau on a charge of heresy in 1534 may have allowed Garamond's reputation to develop in the following decade.[61]

Regardless of these questions about his early career, Garamond's late career is well-recorded, with most of his later roman types (in Lane's view, his best work)[67] preserved in complete sets of matrices at the Museum Plantin-Moretus, which has allowed example sets of characters to be cast, with further documentation and attributions from later inventories and specimen sheets.[68] Of the Garamond types preserved, all include small capitals apart from the gros-canon,[7][68] and the parangonne uniquely includes terminal swash forms for a e m n r t (two forms) and z.[lower-alpha 8]

Italics

Garamond cut more roman types than italics, which at the time were conceived separately to roman types rather than designed alongside them as complementary matches.[74]

Italics had again been introduced by Manutius in 1500; the first was cut by Griffo. This first italic used upright capitals, copying a popular style of calligraphy.[75] The modern italic style of sloped capitals first appeared in 1527 and only slowly became popular.[76] Accordingly, many of Garamond's italics were quite small and had upright capitals. Some of his italics did have sloped capitals, although Vervliet did not feel he integrated them effectively into the typeface design, "sloped capitals were (and stayed) a weakness in his designs."[77]

Garamond's italics were apparently not as used as widely as Granjon's and Haultin's, which spread widely across Europe. For example, on the 1592 Berner specimen, most of the romans were by Garamond but at least all but one, and probably all,[78] of the italics are Granjon's.[79] Similarly in the 1643 Imprimerie royale specimen, most of the italics are Granjon's.[80] (Some books published by Garamond in 1545 use a very common italic of the period, not cut by him.[81])

Greek

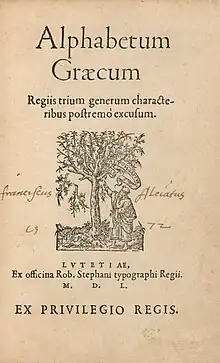

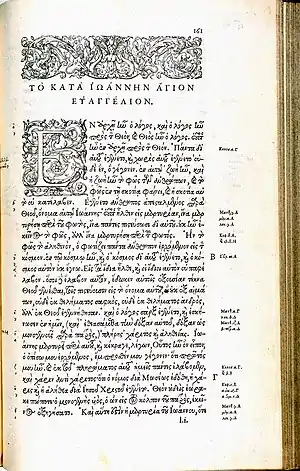

Garamond cut type for the Greek alphabet from the beginning of his recorded career: on 2 November 1540 he contracted to cut a series of Greek faces for the French government, to be used in printing by Robert Estienne.[83][84] The resulting typeface, known as the Grecs du roi, are very different from his Latin designs: again influenced by Greek typefaces used by Manutius (they were cut in three sizes, the same ones Manutius used),[85] they were based on the elegant handwriting of Cretan scribe Angelo Vergecio, who used many ligatures and traditional contractions in his writing, and include a extraordinarily large number of alternate characters to faithfully replicate it.[86][87][88][89] Arthur Tilley called the books printed from them "among the most finished specimens of typography that exist".[90]

The Grecs du roi punches and matrices remain the property of the French government.[91] They were extremely influential and directly copied by many engravers for other printers, becoming the basis of Greek typeface design for the next two centuries.[92]

Although the Grecs du roi style was popular in Greek printing for the next two centuries, it is problematic for modern setting of body text, due to changing tastes in Greek printing: they are slanted, but modern Greek printing often uses upright type, and because Garamond's types were designed assuming that ligatures would be manually selected and inserted wherever needed; later metal types on the same model used fewer ligatures.[93][94][lower-alpha 10] Digital 'Garamond' releases such as Adobe's with Roman and Greek character sets often re-interpret the Greek, for instance with upright characters.[96] A commercial digitisation from Anagrafi Fonts, KS GrequeX, uses the OpenType format to include over 1100 abbreviations and ligatures, more than Garamond cut.[97]

According to Lane the most influential Grecs du roi copies were those of Granjon and Haultin, but others may have been cut by Jean Arnould and Nicolas de Villiers, amongst others.[98] Another was made by Arthur Nicholls in London.[99]

After Garamond's death

Garamond died in 1561 and his punches and matrices were sold off by his widow. Purchasers included the Le Bé type foundry in Paris run by the family of Guillaume Le Bé and Christophe Plantin, who was in Paris at the time; the Frankfurt foundry often referred to by historians as Egenolff-Berner also came to acquire materials of Garamond's.[102][103][104][105] Le Bé's son is known to have written to Plantin's successor Moretus offering to trade matrices so they could both have complementary type in a range of sizes.[106][38][107][lower-alpha 11] Konrad Berner showcased various types of Garamond's and other French engravers in a 1592 specimen, which named the types' engravers and would later be a source for historians.[1][109][lower-alpha 12]

Plantin's collection of original Garamond punches and matrices survives at the Plantin-Moretus Museum in Antwerp, together with many other typefaces collected by Plantin from other typefounders of the period.[111] The collection has been used extensively for research, for example by historians Harry Carter and Vervliet.[112] Plantin also commissioned punchcutter Robert Granjon to create alternate characters for three Garamond fonts with shortened ascenders and descenders to allow tighter linespacing.[113]

Garamond's name was used outside France as a name for 10pt type, often in Dutch as 'Garmond'.[114]

Robert Granjon

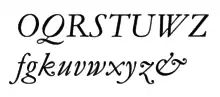

Many modern revival fonts based on French renaissance printing are influenced by the work of Robert Granjon (c. 1513-90), particularly in italic. An engraver with a long and wide-ranging career, Granjon's work seems to have ranged much more widely than Garamond's focus on roman and Greek type, cutting type in italic, civilité (a cursive blackletter), and for the Vatican type in exotic alphabets including Arabic, Armenian and Hebrew. His career also took in stops in the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany and finally for the last twelve years of his life Rome, where he ended his career in the service of the Vatican.

Vervliet comments that Granjon "laid the foundation for our image of the way an Italic should look."[115] Although he was not quite the first designer to use the idea of italics having capitals sloped to complement the roman, he "solved successfully the problem of a balanced inclination of the capitals, a feature much ahead of the designs with a more irregular slope of his Viennese and Mainz predecessors...and even compared to...Garamont. A proper optical harmony of the angle of slope is characteristic for all Granjon’s Italics; it allowed the compositor to use whole lines of capitals without causing too much giddiness."[116][117] Granjon also cut many swash capitals, which Vervliet describes as "deliciously daring" and have often been copied, for instance in Robert Slimbach's revivals for Adobe (discussed below).[116][118]

Other French engravers of the sixteenth century

Besides Garamond, Granjon and the "Estienne master", other engravers were active in the French renaissance style.

Pierre Haultin particularly created many types which were very popular and distributed very widely around Europe: as a Protestant, he spent much of his career outside Paris working in Geneva, Lyons and La Rochelle and his nephew Jérôme established a career importing and casting his types in London, where his types were extremely common.[119] In Carter's view Haultin "has been greatly underrated".[105] Another engraver whose types were very popular in London was François Guyot, who moved from Paris to Antwerp and then London.[120][121][122]

Jean Jannon

In 1621, sixty years after Garamond's death, the French printer Jean Jannon released a specimen of typefaces in the Garamond/Granjon style.[8][123] Jannon wrote in his specimen that:

Seeing that for some time many persons have had to do with the art [of printing] who have greatly lowered it ... the desire came upon me to try if I might imitate, after some fashion, some one among those who honourably busied themselves with the art, [men whose deaths] I hear regretted every day [Jannon mentions some eminent printers of the previous century] ... and inasmuch as I could not accomplish this design for lack of types which I needed ... [some typefounders] would not, and others could not furnish me with what I lacked [so] I resolved, about six years ago, to turn my hand in good earnest to the making of punches, matrices and moulds for all sorts of characters, for the accommodation both of the public and of myself.[38]

Jannon was a Protestant in mostly Catholic France. After apparently working with the Estienne family in Paris he set up an independent career as printer in Sedan in what is now north-eastern France, becoming printer for the Protestant Academy. By his report he took up punchcutting seriously in his thirties, although according to Williamson he would have cut decorative material and engravings at least before this.[23][73] Sedan the time enjoyed an unstable independence as a principality at a time when the French government had conceded through the Edict of Nantes to allowing a complicated system of restricted liberties for Protestants.[124]

The French Royal Printing Office (Imprimerie Royale) appears to have bought matrices from him in 1641 in three large sizes, roman and italic at roughly 18, 24 and 36 point sizes. (The contract is actually made for one 'Nicholas Jannon', which historians have concluded to be a mistake.[125]) Despite the purchase, it is not clear that the office ever much used Jannon's type: historian James Mosley has reported being unable to find books printed by the Imprimerie that use more than two sizes of italic.[lower-alpha 13][24][126] His type would later be misattributed to Garamond.[127] Despite this, it is known that authorities in 1644 raided an office in Caen where he had been commissioned to do printing.[128] Warde initially assumed that this was the source of the Jannon materials in the Imprimerie Nationale before the government's purchase order came to light.[23][38][127][129] Jannon's types and their descendants are recognizable by the scooped-out triangular serifs on the top left of such characters as 'm', 'n' and 'r', which curve to a steeper slant in Jannon's design compared to Garamond's. The italics are also very different from Garamond's own or Granjon's, being much more ornate and with considerable variation in angle of the capitals.[38][130] Opinions of Jannon's engraving quality have varied; Warde found them "so technically brilliant as to be decadent" and "of slight value as a book face" (the surviving Jannon sizes were intended as display faces, cut at 18pt or larger) and Vervliet described them as "famous not so much for the quality of the design but as for the long-term confusion it created", although many reproductions of his work were successful in printing in the twentieth century.[131] Jannon cut far more types than those surviving in the Imprimerie collection: before the misattribution to Garamond, he was particularly respected for his engraving of an extremely small size of type, known for his workplace as sédanoise, which was popular.[73][132][133]

By the nineteenth century, Jannon's matrices had come to be known as the Caractères de l'Université (Characters of the University).[23][126][134] It has sometimes been claimed that this term was an official name designated for the Jannon type by Cardinal Richelieu,[135] while Warde in 1926 more plausibly suggested it might be a garbled recollection of Jannon's work with the Sedan Academy, which operated much like a university despite not using the name. Carter in the 1970s followed this conclusion.[125] Mosley, however, concludes that no report of the term (or much use of Jannon's matrices at all) exists before the nineteenth century, and it may originate from a generic term of the eighteenth century simply meaning older or more conservative typeface designs, perhaps those preferred in academic publishing.[134]

The fate of Garamond's work

.jpg.webp)

The old-style typefaces of Garamond and his contemporaries continued to be regularly used and kept in the stock of European typefounders until the end of the eighteenth century[lower-alpha 14] and appear in the major French type foundry specimen books of the eighteenth century, of Delacolonge,[138][139] Lamesle,[18] and Gando.[140] In Delacolonge's book, many fonts were shown "mutilated" or as "bastard" fonts: with replacement characters, specifically cut-down descenders to allow tighter linespacing.[141] According to James Mosley French renaissance romans remained popular for slightly longer than italics, due to a taste for new italics, wider and with flat incoming serifs, introduced by the Romain du roi type and popularised by Simon-Pierre Fournier (see below): "it is common enough, in the second half of the eighteenth century, to find books set in a Garamond roman or a near copy mated with one of Fournier's italics".[142]

.jpg.webp)

A trademark associated with the Garalde style in modern times is the four-terminal 'W', although sixteenth-century French typefaces generally do not include the character as it is not normal in French. Many French renaissance typefaces used abroad had the character added later, along with the 'J' and 'U': these were often very visibly added by lesser craftsmen, producing an obvious mismatch.[143][144][lower-alpha 16] Granjon added a 'W' and 'w', both with three upper terminals, to Garamond's Breviare roman in 1565 for Plantin.[146]

The foundry of Guillaume Le Bé I which held many of Garamond's punches and matrices passed to Guillaume Le Bé II, and came to be managed by Jean-Claude Fournier, whose son Jean-Pierre in 1730 purchased it.[147] (His younger brother, Simon-Pierre Fournier, rapidly left the family business and became a major exponent of modern ideas in printing, including standardised point sizes and crisp types influenced by contemporary calligraphy.[148])

In 1756, Jean-Pierre Fournier wrote of his collection of vintage equipment that "I am the owner of the foundry of Garamond, the Le Bé family and Granjon. I shall be happy to display my punches and matrices to all those who are lovers of true beauty ... these are the types that made the reputations of the Estiennes, Plantin and the Elzevirs," and referred to an inventory that he said was in his possession that had been drawn up after Garamond's death in 1561.[149][150] (The comment was made in a journal during a public dispute with a printer of more modern tastes who preferred to remain anonymous and may have been his younger brother.[23][151]) The 1561 inventory does not survive, although some later inventories do; by this point Fournier's foundry may have become rather inactive.[152]

Old-style serif typefaces by Garamond and his contemporaries finally fell out of use altogether with the arrival of what is now called the Didone, or modern-face, style of printing in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, promoted by the Didot family in France and others.[23][153][154] This favoured a much more geometric, constructed style of letter which could show off the increasingly refined paper and printing technologies of the period.[155] Lane suggests Fournier's type foundry may have finally disposed of its materials around 1805;[156] in contrast, the collections of the Plantin-Moretus Museum survive almost intact. Mosley comments:[134]

The upheavals of the Revolution coincided with the major shift in the style of printing types that is associated with the family of Didot, and the stock of old materials abruptly lost its value, except as scrap. Punches rust, and the copper of matrices is recyclable. All traces of the early types that had been in the hands of the trade typefounders like Le Bé, Sanlecque and Lamesle in Paris vanished completely. No relics of them were saved anywhere, except in commercial centres that had become relative backwaters, like Antwerp, where the Plantin-Moretus printing office piously preserved the collection of its founder ... the term caractères de l'Université became attached by default to the set of apparently early matrices that had survived, its provenance forgotten, in the mixed stock of materials of the national printing-office.

Garamond's reputation remained respected, even by members of the Didot family whose type designs came to dominate French printing.[24]

Revival era

A revival of interest in 'old-style' serif typefaces took place in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. This saw a revival of the Imprimerie royale typefaces (the office was now called the Imprimerie nationale following the end of the French monarchy), which, unlike Garamond's own work, had survived in Paris. The attribution came to be considered certain by the Imprimerie's director Arthur Christian, who commissioned the cutting of additional sizes in a matching style.[24]

Early revivals were often based directly on the Imprimerie nationale types, one of the first by Peignot and then by American Type Founders (ATF).[157][158] These revivals could be made using pantograph machine engraving systems, which gave a cleaner result than historic typefaces whose master punches had been hand-carved, and allowed rapid development of a family in a large range of sizes.[159][160] In addition, the new hot metal typesetting technology of the period created increasing availability and demand for new fonts. Among hot metal typesetting companies, Monotype's branches in Britain and the United States brought out separate versions, and the American branch of Linotype licensed that of ATF.[38][161]

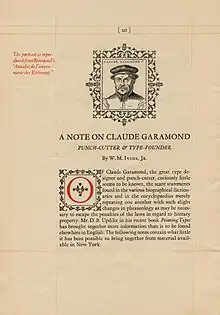

A number of historians began in the early twentieth century to question if the Imprimerie nationale Latin-alphabet type was really the work of Garamond, as the Grecs du Roi undoubtedly were. Doubt was raised by French historian Jean Paillard, but he died during the First World War soon after publishing his conclusions in 1914 and his work remained little-read.[23][24][162][163] ATF's historian Henry Lewis Bullen secretly doubted that the 'Garamond' his company was reviving was really Garamond's work, noting that he had never seen it in a sixteenth-century book. He discussed his concerns with ATF junior librarian Beatrice Warde, who would later move to Europe and become a prominent writer on printing advising the British branch of Monotype.[129][135][164]

In a 1926 paper published on the British typography journal The Fleuron, Beatrice Warde revealed her discovery that the Imprimerie nationale type had been created by Jean Jannon, something she had discovered by examining printing credited to him in London and Paris and through reading the work of Paillard, and perhaps with advice from French bibliographer Marius Audin.[23][38][164][165] (Warde's article was originally published pseudonymously as the work of 'Paul Beaujon', a persona Warde later said she imagined to have a "long grey beard, four grandchildren, a great interest in antique furniture and a rather vague address in Montparesse." Typifying her sense of humour, she reported her conclusions to Morison, a convert to Catholicism, with a telegram beginning "JANNON SPECIMEN SIMPLY GORGEOUS SHOWS ALL SIZES HIS TYPES WERE APPROPRIATED BY RAPACIOUS PAPIST GOVERNMENT ..."[166] She also noted in later life that some of her readers were surprised to see an article supposedly by a Frenchman quoting The Hunting of the Snark.[167])

By the time Warde's article was published some revivals had been released that were more authentic revivals of Garamond's work, based on period books and printing specimens. The German company Stempel brought out a crisp revival of the original Garamond typefaces in the 1920s, inspired by a rediscovered specimen from the Egenolff-Berner foundry in Frankfurt, as did Linotype in Britain.[168][lower-alpha 17]

Timeline

.jpg.webp)

The Renaissance

- 1470 – first book printed in France, by a Swiss/German team at the Sorbonne, Paris.[173] Early books printed in France generally use type of a blackletter design or roman type with blackletter characteristics.

- 1496 – Aldus Manutius publishes De Aetna, a short text of poetry that serves as his first printing in the Latin alphabet. Its roman type sets a standard that would later be imitated by French printers.[174]

Late Renaissance

- 1510 – Garamond may have been born around this time.

- 1530 – Robert Estienne begins to publish in a new and more elegant style of 'roman' type, influenced by De Aetna with its asymmetrical 'M'.

- 1540 – Garamond first clearly enters the historical record, being advanced money to cut the Grecs du Roi type.

- 1561 – Death of Garamond.

- 1563 – Christophe Plantin buys matrices and other equipment in Paris at auction, some from Garamond's widow, for his partnership in Antwerp. Other equipment is bought by other Parisian and German printers; a specimen sheet identifying his types is issued by a Frankfurt foundry in 1592.

- 1560–70s – The work of Garamond and his contemporaries becomes very influential in the Low Countries and western Germany. A decline sets into the production of new typefaces, probably mostly due to simple saturation of the market with typefaces of acceptable quality, and possibly also due to economic and religious factors causing the emigration of printers and typefounders to other countries.[54]

Early modern period

- 1580 – birth of Jannon

- 1621 – Jannon issues a specimen of his type.

- 1640 – Jannon leaves Sedan for Paris.[175]

- 1641 – foundation of the Imprimerie Royale, which buys matrices from Jannon

- 1644 – Jannon's printing office in Caen is raided by authorities concerned that he may have been publishing banned material. Jannon is not imprisoned, but returns to Sedan.[175]

- 1658 – death of Jannon[38]

Eighteenth century

- 1756 – Parisian printer Jean-Pierre Fournier quotes from the 1561 inventory of Garamond's work and writes about his possession of Garamond's equipment. However, his extensive collections are dispersed after his death in 1783 and ultimately 'traditional' old-style type falls out of use in France around the end of the century.

Early revival era

- Late nineteenth century – revival in interest in 'old-style' typefaces such as the Caslon type (1730s, England) and that of Jenson (1470s, Venice).

- 1912 – revival of the Imprimerie Royale (now Imprimerie nationale, following the revolution) type by the Peignot foundry.[24] A revival by Ollière of "Garamond" type based on photographing sixteenth-century books follows

- 1914 – Jean Paillard writes and Ollière publishes an essay showcasing Ollière's Garamond revival arguing that the Imprimerie nationale type was not created by Garamond but his work attracts little attention.[24][163] He is killed serving in the First World War a few months later.

- 1920 – a copy of the 1592 Berner specimen of typefaces is published in facsimile.[24]

- 1923 – ATF issue a specimen of their Garamond revival, in development for several years prior.[24] ATF's historian Henry Bullen privately tells Beatrice Warde, then a junior librarian, that he suspects that Garamond had nothing to do with the type, since he had never seen it in a contemporary book, but has no better candidate for its creator. Warde subsequently moves to Europe, becoming a freelance writer on printing and adviser to Monotype in London.

- 1925 – Based on the Egelhoff-Berner specimen, Stempel Garamond is released in Germany: later also released by Linotype, it is the first Garamond revival actually based on his work.

- 1923 – Monotype Garamond is published based on the Imprimerie nationale type.

- 1926 – Warde discovers and reveals that the Imprimerie nationale type was created by Jannon, and that all revivals based on it are not directly based on Garamond's work.

Contemporary versions

Stempel Garamond

A 1920s adaptation created by the Stempel Type Foundry and released for hot metal typesetting by Linotype, that has remained popular. Its lower case 'a' has a sharp and somewhat angular look with a crisp hook at the top left, in contrast to a teardrop design that is common in many other serif typefaces. Stempel Garamond has relatively short descenders, allowing it to be particularly tightly linespaced.[38][161][176] An unusual feature is the digit 0, which has reversed contrast, with the thickest points of the number on the top and bottom of the digit to make it more distinguishable from an 'o'.[177][178] The Klingspor Museum credits it to Stempel's head of typeface development Dr. Rudolf Wolf.[179]

Garamond No. 1 and Garamond No. 2 are both based on Stempel Garamond, with various differences.[169][180][181] Another typeface known as Original Garamond is a clone of Stempel Garamond.[182]

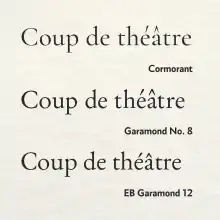

URW++ Garamond No. 8

Garamond No. 8 is a freeware version of Stempel Garamond contributed by URW++ to the Ghostscript project; it was included in GhostScript since Stempel Garamond is included as a system font in some implementations of the PostScript standard.[183] It is distributed under the AFP license, which allows it to be copied freely but not sold.[184] It is understood that its license does not place any restriction on whether the typeface is used in commercial settings (as long as the typeface is not distributed in situations where a fee is involved), nor whether printed contents created with it are sold.[185] Garamond No. 8 hence does not have a fully open-source license, but its license does not restrict usage for personal purposes or commercial printing.

Featuring a bold weight, small capitals, optional text figures and automatic ligature insertion, it is particularly popular in the TeX community and is also included on some Linux distributions.[186] Originally released as a PostScript Type 1, it has been converted into the TrueType format, usable by most current software.[187]

Garamond No. 8 is often packaged as "urw-garamond" in the open source communities,[188][189] but is actually different from another typeface that is simply known as URW Garamond.[190][191]

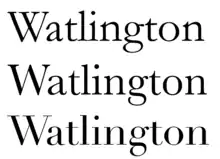

Granjon

Granjon was a 1920s revival designed by George W. Jones for the British branch of Linotype, using a 1582 history textbook as a model and also influenced by Caslon.[38][192][193][194][195] It was the favourite Garalde of many in the twentieth century, including Warde and Walter Tracy.[196]

Jones also created for Linotype Estienne, a delicate revival based on Robert Estienne's fonts of the 1530s discussed above, with very long ascenders and descenders.[197] It was less popular and as of 2017 it has not been officially digitised by Linotype.[198] Williamson suggested that in body text it failed to adapt the style of a large letter effectively down to body text size, giving a design with an extremely small x-height.[199]

Sabon

Sabon is a Garamond revival designed by Jan Tschichold in 1964, jointly released by Linotype, Monotype and Stempel in 1967.[200][201][202] It is named after Jacques Sabon, a Frankfurt-based printer, who introduced the typefaces of Garamond and his contemporaries to German printing.[203] An unusual feature of many releases of Sabon is that the italic, based on Granjon's work, is wider than most normal italics, at the same width as the roman style.[204] This suited Linotype's hot metal typesetting system.[1] Later Sabon versions, such as Jean François Porchez's Sabon Next, have not always maintained this principle.

Tschichold stated that Sabon was designed based on the Egenolff-Berner specimen, although there are different accounts on whether it was drawn using the Saint Augusin (around 13pt) or the Parangon (around 18.5pt) models.[202] Porchez and Christopher Burke later researched into Sabon during the development of Sabon Next. They suggested that aspects of Sabon's design may have been copied from a type by Guillaume Le Bé, a large-size specimen of which he had Tschichold reproduced in a textbook.[202] Sabon Next was based on the version of Sabon that was developed for the Stempel metal handsetting system, along with designs of other Garamond types.[202]

Berthold Garamond

A 1972 revival for phototypesetting issued by H. Berthold and designed by Günter Gerhard Lange.[205][206]

URW Garamond (which is different from URW Garamond No. 8 mentioned above, despite the latter is often packaged as "urw-garamond" in open source software) is a clone of Berthold Garamond.[190][182]

Adobe Garamond

Released in 1989, Adobe Garamond is designed by Robert Slimbach for Adobe Systems following a research visit to the Plantin-Moretus Museum, based on a Roman type by Garamond and an italic type by Robert Granjon.[207][69][208][209][210][211] The font family has 3 weights (Regular, Semibold, and Bold), each with its respective italic, totalling 6 styles.[212] Its quite even, mature design attracted attention on release for its authenticity, in contrast to the much more aggressive ITC Garamond popular at the time.[213][214][215][lower-alpha 18] It is one of the most popular versions of Garamond in books and fine printing.[216] Slimbach decided not to base the design directly on Garamond types in the 9–15pt sizes normally used for book text, but on a larger type called parangonne or vraye parangonne, which he felt was Garamond's "most attractive work".[69][217] It was reviewed by Hugh Williamson for the Printing Historical Society as "well-suited to photocomposition and to offset printing".[211] It also received two detailed reviews in the same issue of Printing History, both a favourable one by Jery Kelly[214] and a more critical one by book designer Mark Argetsinger.[218] Argetsinger felt that while the parangonne type was "a very beautiful design",[219] the choice to base a text type on it produced a type of "relative pallidness" when printed by lithography.[220] He recommended that Adobe add more optical sizes.[221]

Garamond Premier

During the production of Adobe Garamond, its designer Robert Slimbach started planning for a second interpretation of Garamond after visiting the Plantin-Moretus Museum in 1988. He concluded that a digital revival of Garamond's work would not be definitive unless it offered optical sizes, with different fonts designed for different sizes of text.[222] Unable to create such a large range of styles practically with the technology and business requirements of the 1980s, he completed the project in 2005. Adobe states that Garamond Premier was developed based on multiple specimens at the Plantin-Moretus Museum.[223]

Garamond Premier has 4 optical sizes (Regular, Caption, Subhead, and Display) and at least 4 weights (Regular, Medium, Semibold, and Bold, with an additional Light weight for Display), each with its respective italic, totalling 34 styles in the OpenType font format.[224][225][226][227] Garamond Premier and its predecessor Adobe Garamond have the same x-heights, but they have many subtle differences in their designs. At the same weights and x-heights (hence font sizes), Garamond Premier is slightly darker and has tighter spacing than Adobe Garamond. Some other notable differences include (but are not limited to) the designs of the lowercase "t", lowercase "r", and uppercase "Q".

It features glyph coverage for Central European, Cyrillic and Greek characters including polytonics.[227][228][229] Professor Gerry Leonidas, an expert in Greek-language printing, described it in 2005 as "bar none, the most accomplished typeface you can get for complex Greek texts".[230] Adobe executive Thomas Phinney characterized Garamond Premier as a "more directly authentic revival" than their earlier Garamond, which he described as "a more restrained and modernized interpretation".[231]

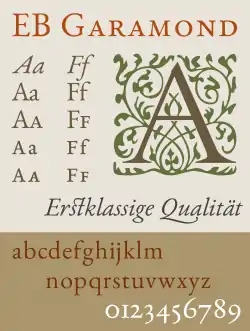

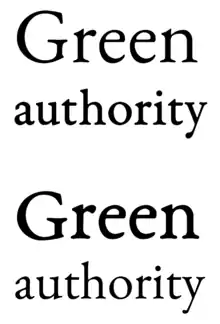

EB Garamond

The EB Garamond («Egenolff-Berner-Garamond»), released by Georg Duffner in 2011 under the Open Font License, is a free software implementation of Garamond.[232] Duffner based the design on the 1592 Berner specimen, with italic and Greek characters based on Robert Granjon's work, as well as the addition of Cyrillic characters and OpenType features such as swash italic capitals and schoolbook alternates.[233] As of 2014, it was intended to include multiple optical sizes, including fonts based on the 8 and 12 point sizes. It has been described as "one of the best open source fonts" by prominent typeface designer Erik Spiekermann.[234] As Georg Duffner was unable to complete the bold weights for personal reasons, the project was continued by Octavio Pardo.[235][lower-alpha 19]

ATF Garamond/Garamond No. 3

American Type Founders created a revival of the Imprimerie Nationale fonts from around 1917, which was designed in-house by its design department led by Morris Fuller Benton under the influence of its historian and advisor Henry Lewis Bullen.[238][239] It received a sumptuous showing, marketed especially towards advertisers, in ATF's 1923 specimen book.[240] Also involved in the design's development was book and advertising designer T.M. Cleland, who created a set of matching borders and ornaments and according to Warde and Garnett also advised on the design and designed the swash characters.[38][193][lower-alpha 20]

While ATF's handset foundry type release was initially popular, the design became particularly known to later users under the name of "Garamond No. 3”, as a hot metal adaptation that was licensed to Linotype's American branch and sold from around 1936. More practical to use than ATF's handset foundry type, the number distinguished it from two versions of Stempel Garamond which Linotype also sold.[169][242] It was the preferred Garalde font of prominent designer Massimo Vignelli.[243]

Several digitisations have been made of both ATF's Garamond and the Linotype adaptation, most notably a 2015 digitisation by van Bronkhorst with optical sizes and the original swash characters.[244][245][246] A loose adaptation with sans-serif companion by Christian Schwartz is the corporate font of Deutsche Bahn.[247]

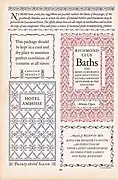

Gallery

Images from American Type Founders' 1923 specimen book.

Monotype Garamond

Monotype's 1922–1923 design, based on Jannon's work in the Imprimerie Nationale, is bundled with Microsoft Office.[248][249] Its italic, faithful to Jannon's, is extremely calligraphic, with a variable angle of slant and flourishes on several lower-case letters.[250] Its commercial release is more extensive than the basic Microsoft release, including additional features such as swash capitals and small capitals, although like many pre-digital fonts these are only included in the regular weight. Popular in the metal type era, its digitisation has been criticised for having too light a colour on the page for body text if printed with many common printing systems, a problem with several Monotype digitisations of the period.[211][251][252][253][254] Monotype's 1933 guide to identifying their typefaces noted the asymmetrical T, the sharp triangular serif at top left of m, n, p and r, and a q unlike the p, with a point at top right rather than a full serif.[255]

Monotype's artistic advisor Stanley Morison wrote in his memoir that the italic was based on Granjon's work, but as Carter's commentary on it notes, this seems generally to be a mistake.[8][125] The swash capitals, however, at least, probably are based on the work of Granjon.[256] A 1959 publicity design promoting it was created by a young Rodney Peppé.[257]

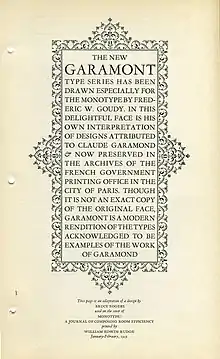

Garamont

A revival by Frederic Goudy for the American branch of Monotype, the name chosen to differ from other revivals.[258][259] An elegant sample created by Bruce Rogers was shown in a spring 1923 issue of Monotype's magazine.[260] It, like Monotype Garamond, features a large range of swash characters, based on Imprimerie Nationale specimen sheets.

Mosley has described it as "a lively type, underappreciated I think."[164] LTC's digitisation deliberately maintained its eccentricity and irregularity true to period printing, avoiding perfect verticals.[261] In 1923, Morison at the British branch of Monotype thought it somewhat florid in comparison to the version of his branch which he considered a personal project, noting in a 1923 letter to American printer Daniel Berkeley Updike that "I entertain very decided opinions about this latest of Mr. Goudy's achievements ... a comparison leaves me with a preference for our version."[262]

Simoncini Garamond

A 1950s version following Jannon by the Simoncini company of Italy, owned by Francesco Simoncini, which sold matrices for Linotype machines.[263] It is particularly popular in Italian printing.

Jannon

František Štorm's 2010 revival with optical sizes is one of the few modern revivals of Jannon's work.[264][265] Štorm also created a matching sans-serif companion design, Jannon Sans.[266]

Related fonts

As one of the most popular typefaces in history, a number of designs have been created that are influenced by Garamond's design but follow different design paths.

ITC Garamond

ITC Garamond was created by Tony Stan in 1975, and follows ITC's house style of unusually high x-height. It was initially intended to serve as a display version but has been used for text, in which its tight spacing and high x-height gives it a somewhat hectoring appearance.[1] As a result, it has proven somewhat controversial among designers; it is generally considered poorly proportioned for body text.[204][267][268] It remains the corporate font of the California State University system in printed text.[269] As seen below, it was also modified into Apple Garamond which served as Apple's corporate font from 1984 until replacement starting in 2002 with Myriad. Publishers using it included O'Reilly Media and French publisher Actes Sud.[204][270][271]

Cormorant

An open-source adaptation of Garamond intended for display sizes, designed by Christian Thalmann and co-released with Google Fonts.[272][273] It features a delicate style suitable for printing at larger sizes, and considerable contrast in stroke weight in its larger sizes. Thalmann added several unusual alternate designs such as an upright italic and unicase styles, as well as exaggerated, highly slanting accents.[274][275]

Sans-serif designs

Several sans-serif typefaces have been published that are based on the proportions of Garamond-style fonts, both as standalone designs or as part of a font superfamily with matching serif and sans-serif fonts.[276] One example is Claude Sans, a humanist sans-serif based on the letterforms of Jannon's type, created by Alan Meeks and published by Letraset and later ITC.[276][277]

In popular culture

- In Umberto Eco's novel Foucault's Pendulum, the protagonists work for a pair of related publishing companies, Garamond and Manuzio, both owned by a Mister Garamond.[278]

- Garamond is the name of a character in the Wii game Super Paper Mario. He appears in the world of Flopside (the mirror-image of Flipside, where the game begins). He is a prolific and highly successful author, unlike his Flipside counterpart, Helvetica.

- For many years the masthead of British newspaper The Guardian used "The" in italic 'Garamond' and "Guardian" in bold Helvetica.[279][280]

- A condensed variant of ITC Garamond was adopted by Apple in 1984 upon the release of the Macintosh, known as Apple Garamond. This was a proprietary font not publicly available, less condensed than the publicly released ITC Garamond Condensed.[281][282]

- One of the initial goals of the literary journal Timothy McSweeney's Quarterly Concern was to use only a single font: Garamond 3. The editor of the journal, Dave Eggers, has stated that it is his favourite font, "because it looked good in so many permutations—italics, small caps, all caps, tracked out, justified or not."[283][284][285]

- In Robin Sloan's fantasy novel Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore several character names derive from historical figures associated with the Garamond typeface.[286]

- In Neil Gaiman's fantasy novel Stardust (Being A Romance Within The Realms of Faerie), one of the realms of Faerie is called Garamond. It is ruled by the Squire of Garamond, whose "only heir was transformed into a Gruntling Pig-wiggin." The realm occurs in the idiom "something is so loud it can be heard from Garamond to Stormhold" and includes an unnamed island in a lake that is the only known origin of a magical herb called Limbus Grass, which compels those who eat it to answer any question truthfully.[287]

Printer ink claim

It has been claimed that Garamond uses much less ink than Times New Roman at a similar point size, so changing to Garamond could be a cost-saver for large organizations that print large numbers of documents, especially if using inkjet printers.[288][289] Garamond, along with Times New Roman and Century Gothic, has been identified by the GSA as a "toner-efficient" font.[290]

This claim has been criticised as a misinterpretation of how typefaces are actually measured and what printing methods are desirable. Monotype Garamond, the version bundled with Microsoft Office,[249] has a generally smaller design at the same nominal point size compared to Times New Roman and quite spindly strokes, giving it a more elegant but less readable appearance. In order to increase the legibility of Garamond, a common approach in typography is to increase text size such that the height of its lower-case characters (i.e., the absolute x-height of the font) matches that of Times New Roman, which counterbalances cost savings. Thomas Phinney, an expert on digital fonts, noted that the effect of simply swapping Garamond in would be compromised legibility: "any of those changes, swapping to a font that sets smaller at the same nominal point size, or actually reducing the point size, or picking a thinner typeface, will reduce the legibility of the text."[248] Professional type designer Jackson Cavanaugh commented "If we're actually interested in reducing waste, just printing less – using less paper – is obviously more efficient."[291]

Gallery

The Plantin-Moretus Museum, which preserves original Garamond punches and matrices.

The Plantin-Moretus Museum, which preserves original Garamond punches and matrices. Garamond's Augustine Romaine punches at the Plantin-Moretus Museum

Garamond's Augustine Romaine punches at the Plantin-Moretus Museum Augustine Romaine punches, detail view

Augustine Romaine punches, detail view Large punches begun by Garamond but unfinished on his death and completed by Jacob Sabon and van den Keere (mirror image).[292]

Large punches begun by Garamond but unfinished on his death and completed by Jacob Sabon and van den Keere (mirror image).[292] Gros-canon matrices

Gros-canon matrices The asymmetrical 'Bembo M' in a French textbook[40]

The asymmetrical 'Bembo M' in a French textbook[40] Monotype Garamond (based on Jannon) compared to the more geometric transitional serif and Didone type that replaced old-styles during the eighteenth century.

Monotype Garamond (based on Jannon) compared to the more geometric transitional serif and Didone type that replaced old-styles during the eighteenth century..jpg.webp) A title page printed in Paris in 1508 showing the style preceding the 1530s: a font dark in colour, with wide capitals, tilted 'e's, large dots on the 'i' recalling calligraphy and blackletter headings.[293]

A title page printed in Paris in 1508 showing the style preceding the 1530s: a font dark in colour, with wide capitals, tilted 'e's, large dots on the 'i' recalling calligraphy and blackletter headings.[293] A very large-size font (c. 120 pt) in a 1551 book by Jean de Tournes, showing Garalde letterforms magnified to display size with sharpened contrast. Designer unknown.[294]

A very large-size font (c. 120 pt) in a 1551 book by Jean de Tournes, showing Garalde letterforms magnified to display size with sharpened contrast. Designer unknown.[294] Frederic Goudy's Garamont type for the American Monotype company in close-up.

Frederic Goudy's Garamont type for the American Monotype company in close-up. The American Monotype's Garamont specimen, showing the capitals.

The American Monotype's Garamont specimen, showing the capitals. The colophon of Monotype's Garamont sample, showing the italic and ligatures.

The colophon of Monotype's Garamont sample, showing the italic and ligatures. Optical sizes in EB Garamond. Top, correct use: large text more delicate, small text more solid. Below, wrong way round.

Optical sizes in EB Garamond. Top, correct use: large text more delicate, small text more solid. Below, wrong way round. A specimen of František Štorm's revival of Jannon's type with bold and sans-serif derivatives.

A specimen of František Štorm's revival of Jannon's type with bold and sans-serif derivatives.

Plantin painted posthumously by Rubens.

Plantin painted posthumously by Rubens.

Notes

- However, this is a statement from early in Vervliet's career. In his later career Vervliet came to believe that Garamond's types were based on others cut by a punchcutter named "Constantin"-see below.

- This is a slight simplification - technically the mould is an interchangeable part which is clamped around a matrix to cast type. However, the matrix is the mould for the letterform part of a sort.

- A Le Bé foundry inventory also records a very small blackletter cut by Garamond. No printing using it is known, although Harry Carter suggested a type in the Delacolonge specimen book could be it with some altered characters.[19]

- Later five

- Anglo-American point size; 40pt Didot scale[35]

- Lane suggests it was probably made in Antwerp for Plantin by Hendrik van den Keere.[55]

- Regarding Constantin, Carter (who believed that the Estienne romans were by Garamond)[33] suggested very tentatively that he might have had some connection to a known book editor from Lyons with the same surname, and notes that the document previously mentions that the Aldine style was imitated in Lyons and in Paris.[64] A counter-suggestion is that of Kay Amert, who proposed that Estienne's typefaces were variant states of ones used, and probably cut by, his stepfather Simon de Colines,[65][36] but Vervliet rejects this as unlikely: "it seems unlikely that Estienne would have parted from his punches or that Colines would have refurbished them to an inferior level."[66]

- All the terminal forms apart from the 'm' were digitised with Adobe Garamond Pro.[69]

- Hugh Williamson suggested that some uses of this italic included characters not cut by Garamond.[73]

- Gerry Leonidas, a leading expert on Greek typesetting, has commented that Vergecio's handwriting "has all the marks of a script that is unsuitable for conversion to [printing]. That it was the model for the widely-copied grecs du roi was, with hindsight, unfortunate."[95]

- A large number of fragments of specimens of types from the Le Bé foundry survive at the Plantin-Moretus Museum, connected to this trade–extremely usefully for historians, as no complete Le Bé foundry specimen survives.[108]

- The 1592 Berner specimen, now in the Stadt- und Universitätsbibliothek, Frankfurt am Main, was misfiled for some years after the Second World War, and is therefore reported as believed lost in some post-war histories.[110]

- Mosley did caution about the limits of what he could check: "it is not easy to prove a negative".

- In some niche cases, such as a small Greek probably by Haultin, into the nineteenth.[136][137]

- The crudeness of the 'W' compared to other capitals suggests that it might not have been part of the original font.

- According to the showings cast by the Plantin-Moretus Museum of their Garamond faces intended to include no characters added later, none of their Garamond types include a 'J', capital 'U' or 'W' considered part of the original type.[7][145]

- Linotype's British version, Granjon, was an original creation. The American branch's version, Garamond No. 3, was licensed from American Type Founders, while there and in Germany Linotype also licensed and modified that of Stempel. These versions are discussed separately below under these names.[169][170]

- A remastering in the modern OpenType font format was released in 2000 as Adobe Garamond Pro.[69]

- As of 2018, this implementation has 5 weights (Regular, Medium, Semi-Bold, Bold and Extra-Bold), both in regular and italic style. The font files in both common flavours (OTF and TTF) can be downloaded from Pardo's repository[236] and are also available for embedding on Google Fonts, but in an, according to Duffner, ”utterly outdated” version.[237]

- Porter Garnett, in his 1927 showcase and account of running the Carnegie Institute of Technology printing course in the 1920s (which is set in ATF Garamond), provides a contemporary commentary on its genesis: "Garamond (made available to American printers in 1920) was designed by Mr. Morris F. Benton, after the caractères de l'Université attributed to the sixteenth century punch-cutter Claude Garamond (or Garamont). It has remained for Mrs. Beatrice Becker Warde ("Paul Beaujon") to prove [their origin] to Jean Jannon, of Sedan…

The forms of certain letters of the roman font, as first issued by the American Type Founders Company, were, upon the suggestion of Mr. T.M. Cleland, subsequently modified. The E, F and L were made more narrow, the J longer, the U wider, and the lower termination of the & altered. Mr. Cleland also designed a series of swash letters for the italic. The numerals originally issued with the font were of the highly objectionable "ranging" variety, but my solicitations (after two years of…using wrong-font sorts in their stead) finally extracted non-ranging numerals from the founders. I induced them also to make three ligatures Qu, Qu and Qu [with a Caslon-style calligraphic 'Q'], and a k and z [with descending flourishes similar to those on Monotype Garamond], which were used for the first time in "That Endeth Never".[241] - An accessible comparison is Warde, p. 166.[38]

References

- "Just what makes a Garamond a Garamond?". Linotype. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- Johnson, Alfred F. (1936). "Sources Of Roman And Italic Types Used By English Printers In The Sixteenth Century". The Library. Series 4. XVII (1): 70–82. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XVII.1.70.

- Carter, Matthew (1985). "Galliard: A Revival of Types of Robert Granjon". Visible Language. 19 (1): 77–98. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- Amert 2012, p. 21.

- Phil Baines; Andrew Haslam (2005). Type & Typography. Laurence King Publishing. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-1-85669-437-7.

- Mosley, James (1960). "New Approaches to the Classification of Typefaces". The British Printer (Reprinted for the United States House Committee on the Judiciary).

- Vervliet, Hendrik. "Conspectus of French Renaissance Printing Types (online errata)" (PDF). Bibliographical Society of London. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- Dearden, James (1973). Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science: Claude Garamond. New York u.a.: Dekker. pp. 196–199. ISBN 978-0-8247-2109-1. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- Tracy 2003, pp. 58–59.

- Burnhill, Peter (2003). Type spaces: in-house norms in the typography of Aldus Manutius. Hyphen Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-907259-53-4. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

[Quoting a letter from James Mosley]: Leading of text matter for aesthetic reasons is largely an 18th-century (and later) habit...My observations of printing in earlier centuries suggests that the founders generally cast types to fit the body very tightly, and that printers used them without leading.

- Carter, Harry (1937). "Optical scale in type founding". Typography. 4. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Argetsinger 1991–1992, pp. 74–75.

- Lane 2005.

- Vervliet, H. D. L. (1965). "The Garamond Types of Christopher Plantin". Journal of the Printing Historical Society. 1: 14–20.

- Haley, Allan. "Bold type in text". Monotype. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- Lawson, Alexander (27 June 1982). "To the Editor (letter)". New York Times. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 223.

- Lamesle, Claude (1742). Épreuves générales des caracteres qui se trouvent chez Claude Lamesle. Rue Galande, Paris: Claude Lamesle. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Carter 1969, pp. 70, 93.

- "Blackletter typefaces". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "The first Parisian workshops". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- "Italian typefaces". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- Mosley, James. "Garamond or Garamont". Type Foundry blog. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Mosley, James (2006). "Garamond, Griffo and Others: The Price of Celebrity". Bibliologia. 1 (1): 17–41. doi:10.1400/53248. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Amert, Kay (April 2008). "Stanley Morison's Aldine Hypothesis Revisited". Design Issues. 24 (2): 53–71. doi:10.1162/desi.2008.24.2.53. S2CID 57566512.

- Nesbitt 1998, p. 100. "It is generally acknowledged that Garamond did not cut a good italic: he does not seem to have been interested in this type form. The two italics he cut for his own venture into the publishing field were poor imitations of the Aldine letter."

- Barker 2003, p. 194.

- "Aldus Manutius and his innovations". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "The Italics". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- The Aldine Press: Catalogue of the Ahmanson-Murphy Collection of books by or relating to the press in the library of the University of California, Los Angeles incorporating works recorded elsewhere. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. 2001. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-520-22993-8.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 114–118.

- Barker 2003, pp. 196–198.

- Carter 2002, p. 84.

- Barker 2003, pp. 198–202.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 15.

- Amert, Kay (June 2005). "The Phenomenon of the "Gros Canon"". The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. 99 (2): 231–263. doi:10.1086/pbsa.99.2.24295917. S2CID 163211830.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 105–111, 113–121.

- Warde, Beatrice (1926). "The 'Garamond' Types". The Fleuron: 131–179.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 88, 110, 156, 165, 171.

- Olocco & Patanè 2022, p. 59.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 156.

- Vervliet 2010, pp. 32–34.

- Vervliet 2010, pp. 23–25.

- Armstrong 2011, pp. 51–52.

- Lubell, Stephen (15 May 2014). Sixteenth-century Hebrew typography: A typographical and historical analysis based on the Guillaume I Le Bé documents in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (doctoral). University of London (PhD thesis).

- Lane 2005, p. 6.

- Vervliet 2010, p. .

- Vervliet 2008, p. 1.

- "The Career of a Punch-Cutter". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "The spread of Garamond". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Johnson, A. F. (1938). "Some types used by Paolo Manuzio". The Library. Series 4. XIX (2): 167–175. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XIX.2.167.

- "Garamont the bookseller". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Garamont's will". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Vervliet 2010, pp. 23–32, 39–40, etc..

- Lane 2005, pp. 234–235.

- Carter 2002, pp. 83–87.

- Carter, Harry; Morison, Stanley (1967). Sixteenth-century French Typefounders: The Le Bé memorandum. Private printing for A. Jammes.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 167–171.

- "Who invented Garamond?". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "The Roman typefaces". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 164–165.

- Armstrong 2011, pp. 48–49.

- Mosley, J. (23 June 2011). "The Palaeotypography of the French Renaissance: Selected Papers on Sixteenth-Century Typefaces. By HENDRIK D. L. VERVLIET. (Library of the Written Word, 6; The Handpress World, 4.) * French Renaissance Printing Types: A Conspectus. By HENDRIK D. L. VERVLIET". The Library. 12 (2): 175–178. doi:10.1093/library/12.2.175.

- Barker 2003, p. 214.

- Amert 2012.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 178.

- Lane 2005, p. 10.

- Vervliet 2010.

- Adobe Garamond Pro specimen book (PDF). San José: Adobe Systems. 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- Vervliet & Carter 1972, p. 14.

- Vervliet 2010, p. 325.

- Lane 2004, p. 316.

- Williamson, Hugh (1987). "Jean Jannon of Sedan (series of articles)". Bulletin of the Printing Historical Society.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 287–320.

- Kaufmann, Ueli (11 October 2015). "The design and spread of Froben's early Italics". Department of Typography & Graphic Communication. University of Reading. Archived from the original on 2 November 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- Clair, Colin (1969). A Chronology of Printing. New York, Praeger. p. 43.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 319.

- Dreyfus 1963, pp. 4–6.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 346.

- Veyrin-Forrer, Jeanne; Jammes, André, eds. (1958). Les premiers caractères de l'Imprimerie Royale: étude sur un spécimen inconnu.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 288–298, 312.

- Valerie R. Hotchkiss, Charles C. Ryrie (1998). "Formatting the Word of God: An Exhibition at Bridwell Library". Archived from the original on 9 January 2009.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 383.

- Parent, Annie; Veyrin-Forrer, Jeanne (1974). "Claude Garamont: New Documents". The Library. Series 5. XXIX (1): 80–92. doi:10.1093/library/s5-XXIX.1.80.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 386.

- "Garamont's early career: the grecs du roi". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "The Greek Typefaces". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Mosley, James. "Porson's Greek type design". Type Foundry. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- Armstrong 2011, p. 52.

- Tilley, Arthur (1900). "Humanism under Francis I". The English Historical Review. 15 (59): 456–478. doi:10.1093/ehr/xv.lix.456.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 130–131, 133–134.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 388.

- Lane 1996, pp. 117–123.

- Pektas, Nil Ozlem. The First Greek Printing Press in Constantinople (1625‐1628) (PDF) (PhD thesis). Royal Holloway. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- Leonidas, Gerry (2002). "A primer on Greek type design". In Berry, John D. (ed.). Language Culture Type: International Type Design in the Age of Unicode. ATypI. pp. 80–83. ISBN 978-1-932026-01-6.

- Slimbach 2005, p. 20.

- Siskakis, Constantine F. "KS GrequeX". Anagrafi Fonts. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Lane 1996, pp. 109–111.

- Lane, John A. (1991). "Arthur Nicholls and his Greek Type for the King's Printing House". The Library. Series 6. 13 (4): 297–322. doi:10.1093/library/s6-13.4.297.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 220.

- Dreyfus 1963, p. 3.

- "Claude Garamond". linotype.com. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- van Uchelen, Ton Croiset; Dijstelberge, P., eds. (2013). Dutch typography in the sixteenth century the collected works of Paul Valkema Blouw. Leiden: Brill. p. 426. ISBN 978-90-04-25655-2.

- Blouw, Paul Valkema (1 January 1990). "Willem Silvius's remarkable start, 1559-62". Quaerendo. 20 (3): 167–206. doi:10.1163/157006990X00175.

- Carter 2002, pp. 86–87.

- Lane 2005, p. 240.

- Updike 1922, pp. 6–7, "Chapter 15: Types of the Netherlands, 1500–1800".

- Vervliet & Carter 1972, pp. 12–15.

- Specimen Charactervm Sev Typorvm Latinorvm Probatissimorvm. Frankfurt am Main: Univ.-Bibliothek. 1592. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- Carter 2002, p. 19 98.

- Mosley, James. "The materials of typefounding". Type Foundry. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- Carter 2002, pp. 9–10.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 216.

- Reed, Talbot Baines (1887). A History of the Old English Letter-Foundries. London. pp. 38–39.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vervliet 2008, p. 322.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 321–364.

- Johnson, A. F. (1940). "The Italic Types of Robert Granjon". The Library. Series 4. XXI (3–4): 291–308. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XXI.3-4.291.

- Shaw 2017, pp. 48–69.

- Vervliet 2008, pp. 243–286.

- Carter 2002, p. 96.

- Werner, Sarah (22 September 2011). "Guyot's speciman [sic] sheet". The Collation. Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- Gaultney 2021, p. 44.

- Dunlap, David W. (23 December 2011). "Printing for Kingdom, Empire & Republic: Treasures From the Archives of the Imprimerie Nationale (exhibition review)". New York Times. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Maag, Karin (2002). "The Huguenot academies: an uncertain future". In Mentzer, Raymond; Spicer, Andrew (eds.). Society and culture in the Huguenot world : 1559–1685. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 139–156. ISBN 978-0-521-77324-9. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Morison 1973, p. 129.

- Mosley, James. "The types of Jean Jannon at the Imprimerie royale". Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Jannon". French Ministry of Culture.

- Shalev, Zur (2012). "Samuel Bochart's Protestant Geography". Sacred words and worlds: geography, religion, and scholarship, 1550–1700. Leiden: Brill. pp. 141, 164. ISBN 978-90-04-20935-0. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Haley 1992, pp. 125–127.

- Gaultney 2021, p. 63.

- Nesbitt 1998, pp. 126–127.

- Thomas Hartwell Horne (1814). An Introduction to the Study of Bibliography ; to which is Prefixed a Memoir on the Public Libraries of the Ancients. G. Woodfall. p. 81.

- Boulliot, Jean-Baptiste-Joseph (1830). Biographie ardennaise, ou Histoire des Ardennais qui se sont fait remarquer par leurs écrits, leurs actions, leurs vertus ou leurs erreurs. pp. 56–61.

- Mosley, James. "Caractères de l'Université". Type Foundry. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Loxley, Simon (31 March 2006). Type. Bloomsbury. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-0-85773-017-6.

- Vervliet 2008, p. 270.

- Lane 1996, p. 115.

- Carter 1969.

- Delacolonge (1773). Les Caracteres les vignettes de la fonderie du sieur Delacolonge. Lyon. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- Johnson, A. F. (1937). "The Type-Specimen Books of Claude Lamesle and Nicolas Gando". The Library. Series 4. XVIII (2): 201–211. doi:10.1093/library/s4-xviii.2.201.

- Carter 1969, pp. 15–16.

- Mosley 1965, p. 15.

- Lane, John A. (1995). "Arent Corsz Hogenacker (ca. 1579-1636): an account of his typefoundry and a note on his types Part two: the types". Quaerendo. 25 (3): 163. doi:10.1163/157006995X00017.

Most of these sixteenth-century types were originally cut without the letters J, U, and W, which were added in the seventeenth century.

- Nuttall, Derek (1987). "English printers and their typefaces, 1600-1700". In Myers, Robin; Harris, Michael (eds.). Aspects of Printing from 1600. Oxford: Oxford Polytechnic Press. ISBN 0902692364.

[English] type-casters...were thrust into punch-cutting in order to make up deficiencies in founts, especially of letters like the J and U which were required in English printing...several crude versions of these letters which are found intermixed with letters of refined design, strongly suggest that the cutter had received little or no training in the art of punch-cutting.

- Vervliet 2010, pp. 57, 97, 117, 144, 205.

- Lane 2004, p. 199.

- Mosley 1965, p. 3.

- Mosley 1965, pp. 3–4.

- "Garamond's lasting influence". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Fournier, Jean-Pierre (1756). "Lettre de M. Fournier". Mercure de France: 121–122. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Anonymous (1756). "Réponse à une autre Lettre inférée dans le Mercure de Mai dernier". Journal des sçavans: 21–25. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Lane 2005, pp. 239–243.

- Updike 1922, p. , "French Types, 1500–1800".

- "The French Revolution and the Didots". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Phinney, Thomas. "Transitional & Modern Type Families". Graphic Design and Publishing Centre. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- Lane 2004, pp. 241–242.

- "Early 20th century interpretations (I)". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Early 20th century interpretations (II)". French Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Morison, Stanley. "Printing the Times". Eye. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Monotype matrices and moulds in the making" (PDF). Monotype Recorder. 40 (3). 1956.

- "Illuminating Letters Number One: Garamond" (PDF). Monotype Imaging. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Morison 1973, pp. 129–130.

- Paillard, Jean (1914). Claude Garamont, graveur et fondeur de lettres. Paris: Ollière. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Mosley, James (20 September 2007). "Comments on 'Garamond is not Garamond' thread". Typophile. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- Audin, Marius (1933). "Fonderie de Lettres et les Fondeurs Français 1933". Arts et Metiers Graphiques: 45–49. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Haley 1992, p. 126.

- De Bondt, Sara (Autumn 2012). "Beatrice Warde: Manners and type". Eye Magazine. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Stempel Garamond LT". Linotype. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- Shaw, Paul. "The Mystery of Garamond No. 3". Blue Pencil. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- Haley, Allan (1999). "A Flock of Garamonds". Step Inside Design. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016.

- Barker 2003, p. 190.

- Barker 2003, p. 198.

- Andrew Pettegree; Malcolm Walsby (14 October 2011). French Books III & IV: Books published in France before 1601 in Latin and Languages other than French. BRILL. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-90-04-21500-9.

- Boardley, John (18 April 2016). "The First Roman Fonts". i love typography. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Malcolm, Noel (2002). Aspects of Hobbes. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 267–268. ISBN 978-0-19-152998-6. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Claude Garamond (14 September 2000). "Stempel Garamond". Linotype. Retrieved 9 October 2015 – via MyFonts.

- Walters, John (2 September 2013). Fifty Typefaces That Changed the World. Octopus. ISBN 978-1-84091-649-2. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- Bergmann, Christoph; Hardwig, Florian (23 August 2016). "Zero vs. oh: Strategies of glyph differentiation". Isoglosse. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Schriftdesigner Rudolf Wolf". Klingspor Museum. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Garamond No. 1 in use - Fonts In Use". Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- "Garamond No. 2 in use - Fonts In Use". Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- "Fake (faux) versus true Garamond". Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- "Font Substitutions table". Ghostscript. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "GaramondNo8 1.06 LICENSE.txt". Garamond.org. 6 June 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- "legal - Can URW Garamond No8 be used in a printed book? - Graphic Design Stack Exchange". Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- Hartke, Stephen. "A Survey of Free Math Fonts for TeX and LaTeX". The PracTeX Journal. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Hosny, Khaled. "URW Garamond ttf conversions". Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "CTAN: Package urw-garamond". Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- "AUR (en) - urw-garamond". Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- "URW Garamond in use - Fonts In Use". Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- "Garamond Font". Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- Claude Garamond; Robert Granjon; Chauncey Griffith; George Jones (14 September 2000). "Granjon LT". Linotype. Retrieved 3 December 2015 – via MyFonts.

- Lawson, Alexander (June 1967). "Variations of Garamond". Printing Impressions. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- Lawson, Alexander (1990). Anatomy of a Typeface (1st ed.). Boston: Godine. pp. 147–151. ISBN 978-0-87923-333-4.

- McMurtrie, Douglas. The Book - The Story of Printing & Bookmaking. p. 580.

Personally I know of no typeface which rates higher...I once told Mr. Jones that Granjon appeared to me to be fifty per cent Garamond and fifty per cent Caslon. He replied: "Your diagnosis is just about correct." Certainly he drew on sound precedents!

- Tracy 2003, pp. 143–144, etc.