Gauliga

A Gauliga (German pronunciation: [ˈɡaʊˌliːɡa]) was the highest level of play in German football from 1933 to 1945. The leagues were introduced in 1933, after the Nazi takeover of power by the National Socialist League of the Reich for Physical Exercise.

| |

| Founded | 1933 |

|---|---|

| Folded | 1945 |

| Replaced by | Oberliga |

| Country | |

| Level on pyramid | Level 1 |

| Domestic cup(s) | Tschammerpokal |

| Last champions | Dresdner SC (1943–44) |

Name

The German word Gauliga is composed of Gau, approximately meaning county or region, and Liga, or league. The plural is Gauligen. While the name Gauliga is not in use in German football any more, mainly because it is attached to the Nazi past, some sports in Germany still have Gauligen, like gymnastics and faustball.

Overview

The Gauligen were formed in 1933 to replace the previously existing Bezirksligas in Weimar Germany. The Nazis initially introduced 16 regional Gauligen, some of them subdivided into groups. The introduction of the Gauligen was part of the Gleichschaltung process, whereby the Nazis completely revamped the domestic administration. The Gauligen were largely formed along the new Gaue, designed to replace the old German states, like Prussia and Bavaria, and therefore gain better control over the country.

This step came as a disappointment to many more forward thinking football officials, like the Germany national team managers Otto Nerz and Sepp Herberger,[1] who had hoped for a Reichsliga, a unified highest competition for all of Germany, like the ones already in place in countries like Italy (Serie A) and England (The Football League). Shortly before the Nazis came to power, the DFB started to seriously consider the establishment of such a national league. In a special session on 28 and 29 May 1933, a decision was to be made on the establishment of the Reichsliga as a professional league. Four weeks before that date, the session was cancelled, professionalism and Nazi ideology did not agree with each other.[2] With the disappointing performance of the German team at the 1938 FIFA World Cup, the debate about a Reichsliga was reopened. In August 1939, a meeting was to be held to decide on the creation of a league system of six Gauligen as a transition stage to the Reichsliga, but the outbreak of the Second World War shortly after ended this debate, too.[2] In reality, this step was not taken until 1963, when the Bundesliga was formed, for similar reason, after the disappointing performance at the 1962 FIFA World Cup.[3] It did, however, reduce the number of clubs in top leagues in the country considerably, from roughly 600 to 170.[4]

Beginning in 1935, with the re-admittance of the Saarland into Germany, the country and the leagues began to expand. With the aggressive expansion politics, and later, through the Second World War, Germany grew considerably in size. New or regained territories were incorporated into Nazi Germany. In those regions incorporated into Germany, new Gauligen were formed.[5]

With the outbreak of the Second World War, football continued but competitions were reduced in size as many players were drafted to the German Wehrmacht. Most Gauligen split into subgroups to reduce travel, which became increasingly more difficult as the war went on.

Many clubs had to merge or form Kriegsgemeinschaften (war associations) due to lack of players. The competition became increasingly flawed as the list of available players to a club fluctuated on a weekly basis, depending on who was where at a time.

The last season, 1944–45, was never completed, as large parts of Germany were already under allied occupation and the German unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945 ended all sports competitions, the last official match having been played on 23 April.

Finances

Unlike most leagues today, where income is generated from sponsors and TV in addition to ticket sales, the Gauliga teams relied on ticket sales as the exclusive source of income. But while in today's leagues the hosting teams keep the cash from the ticket sales, this was handled differently in the Gauligen. In the regular season, in cup matches or other competitive matches, the money was shared between the German Football Association, who received 5% of the income, the hosting club and the visiting club. In particular, the hosting club received 10% for using their ground and 5% for administrative costs. The remaining 75% of the matchday income were shared between the two clubs. These relations changed for the play-offs for the German championship. Here the matches were usually played on neutral ground, therefore 15% of the income were allotted for renting the ground as well as administrative and travel costs for the teams. The remaining income was divided equally between the clubs and the DFB. For the semi-final and final matches, yet another distribution key was applied. In the semi-final, teams received 20% of the net income (that is, after rent, administrative and travel costs had been deducted) and in the final their share was reduced to 15%.[6]

Aftermath

While some areas took until 1947, to restart football competitions, in the south of Germany, a highest league was formed soon after the Nazi collapse. The new Oberligen took the place of the Gauligen from 1945, when six new leagues were gradually formed in what was left of Germany:

- Oberliga Süd, formed in 1945

- Oberliga Südwest, formed in 1945

- Oberliga Berlin, formed in 1945

- Oberliga Nord, formed in 1947

- Oberliga West, formed in 1947

- DDR-Oberliga, formed in 1949, disbanded in 1991 after German reunification

Influence of the Nazis in football

With the rise of the Nazis to power, the German Football Association came fully under the party's influence. All sport, including football, was controlled by the Reichssportführer (Reich Sports Leader) Hans von Tschammer und Osten. In 1935, the newly established German cup, the Tschammerpokal, now the DFB-Pokal, was named after him. The Nazis prohibited all workers sports clubs (Arbeiter Sportvereine) and, increasingly so, all Jewish sport associations. Jewish clubs were immediately removed from all national football competitions in 1933 and had to play their own tournaments. From 1938, all Jewish sport clubs were forbidden outright.[7]

Additionally, clubs with strong connections to Jews were punished and fell into disfavor, like Bayern Munich, who had a Jewish coach (Richard Dombi) and chairman (Kurt Landauer).[8] After the annexation of Austria in 1938, FK Austria Wien, another club with strong Jewish ties, suffered from persecution and many of the club's leaders, like its chairman Emanuel Schwarz, had to escape to survive the Nazi regime.[9] Apart from those two clubs, the VfR Mannheim, VfB Mühlburg, 1. FC Kaiserslautern, Stuttgarter Kickers, Eintracht Frankfurt and FSV Frankfurt had all benefited in their pre-1933 success from a strong Jewish membership in the clubs and found themselves initially unpopular with the Nazis. Even though Jews were soon removed from all these clubs, some retained a more open-minded attitude than others and continued to be out of favour with the Nazis. The players of Bayern Munich for example were heavily criticised for greeting their former chairman Landauer at a friendly at Servette Geneva in Switzerland.[10]

The Nazis were, however, interested in furthering sport, especially football, as success in the sport served their propaganda efforts. Hans von Tschammer und Osten specifically ordered that players from former workers' sports movements be integrated in the Nazi-approved clubs, as the Nazis could not afford to lose the country's best players. Upon his orders, teams were not selected by political criteria, but by performance criteria.

Despite this, the number of active players and clubs declined in regions like the Ruhr area, where the workers' movement was traditionally strong.[11]

The fact that some famous players, like FC Schalke 04's Tibulski, Kalwitzki, Fritz Szepan, and Ernst Kuzorra, had less-than-German-sounding names and were mostly descendants of Polish immigrants, was ignored by the Nazis. On the contrary, players like Szepan successfully represented Nazi Germany in the 1934 and 1938 World Cups.[12] Jewish players like the two former internationals Gottfried Fuchs and Julius Hirsch were not as welcome. Fuchs, who had scored an incredible 10 goals versus Russia in 1912, migrated to Canada, while Hirsch was murdered in Auschwitz.[10]

In occupied territories

The Nazis' position to football and its clubs in the occupied territories varied greatly. Local clubs in Eastern Europe, such as Polish and Czech clubs, were not permitted to compete in the Gauligen. The situation was different in Western Europe, where clubs from Alsace, Lorraine, and Luxembourg took part in the Gauliga system under Germanised names.

Clubs with a Czech majority, while part of the German Reich, played out their own national, Bohemia/Moravia championship in this time, parallel to the German Gauliga Böhmen und Mähren, but were racially segregated.[13]

German championship

The winners of the various Gauligen qualified for the finals of the German championship, held at the end of season.

From 1934 to 1938, the system was straight forward, as the 16 Gauliga champions were allocated in four groups of four teams. After a home-and-away round, the winners of the four groups played a semi-final on neutral ground. The two winners of the semi-finals went to the final to determine the German champion.

In the years 1939, 1940, and 1941, the number of groups was extended to compensate for the additional Gauligen created.

From 1942, the competition was played in a single-game knock-out format due to the worsening situation in the war.

While FC Schalke 04 was by far the most successful club in this era, however in 1941 the title went to Austria with Rapid Wien. Also, a Luxembourgian club, Stade Dudelange (renamed FV Stadt Düdelingen), managed to reach the first round of the championship and cup in 1942.

German championship finals under the Gauliga system

| Year | Champion | Runner-Up | Result | Date | Venue | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1944 | Dresdner SC | LSV Hamburg | 4–0 | 18 June 1944 | Berlin | 70,000 |

| 1943 | Dresdner SC | FV Saarbrücken | 3–0 | 27 June 1943 | Berlin | 80,000 |

| 1942 | FC Schalke 04 | First Vienna FC | 2–0 | 5 July 1942 | Berlin | 90,000 |

| 1941 | Rapid Wien | FC Schalke 04 | 4–3 | 22 June 1941 | Berlin | 95,000 |

| 1940 | FC Schalke 04 | Dresdner SC | 1–0 | 21 July 1940 | Berlin | 95,000 |

| 1939 | FC Schalke 04 | Admira Wien | 9–0 | 18 June 1939 | Berlin | 100,000 |

| 1938 | Hannover 96 | FC Schalke 04 | 3–3 aet 4–3 aet | 26 June 1938 3 July 1938 | Berlin Berlin | 100,000 100,000 |

| 1937 | FC Schalke 04 | 1. FC Nürnberg | 2–0 | 20 June 1937 | Berlin | 100,000 |

| 1936 | 1. FC Nürnberg | Fortuna Düsseldorf | 2–1 aet | 21 June 1936 | Berlin | 45,000 |

| 1935 | FC Schalke 04 | VfB Stuttgart | 6–4 | 23 June 1935 | Cologne | 74,000 |

| 1934 | FC Schalke 04 | 1. FC Nürnberg | 2–1 | 24 June 1934 | Berlin | 45,000 |

German cup finals under the Gauliga system

The German Cup competition was first played out in 1935 and ceased in 1943, only restarting again in 1953. During Nazi Germany, it was called The von Tschammer und Osten Pokal.

| Year | Winner | Finalist | Result | Date | Venue | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1943 | First Vienna FC | LSV Hamburg | 3–2 aet | 31 October 1943 | Stuttgart | 45,000 |

| 1942 | TSV 1860 Munich | FC Schalke 04 | 2–0 | 15 October 1942 | Berlin | 80,000 |

| 1941 | Dresdner SC | FC Schalke 04 | 2–1 | 2 October 1941 | Berlin | 65,000 |

| 1940 | Dresdner SC | 1. FC Nürnberg | 2–1 aet | 1 December 1940 | Berlin | 60,000 |

| 1939 | 1. FC Nürnberg | SV Waldhof Mannheim | 2–0 | 8 April 1940 | Berlin | 60,000 |

| 1938 | Rapid Wien | FSV Frankfurt | 3–1 | 8 January 1939 | Berlin | 38,000 |

| 1937 | FC Schalke 04 | Fortuna Düsseldorf | 2–1 | 9 January 1938 | Köln | 72,000 |

| 1936 | VfB Leipzig | FC Schalke 04 | 2–1 | 3 January 1937 | Berlin | 70,000 |

| 1935 | 1. FC Nürnberg | FC Schalke 04 | 2–0 | 8 December 1935 | Düsseldorf | 55,000 |

List of Gauligen

Original Gauligen in 1933

- Gauliga Baden: covering the state of Baden, split into a varying number groups after 1939

- Gauliga Bayern: covering the state of Bavaria without the Palatinate region, split into a northern and southern division from 1942, split into five separate groups in 1944

- Gauliga Berlin-Brandenburg: covering what is now the federal states of Berlin and Brandenburg, both part of Prussia until 1945, in the 1939–40 season in two groups

- Gauliga Hessen: covering what is now the federal state of Hesse except the Frankfurt (Mainhessen) region, split into a varying number groups after 1939, renamed Gauliga Kurhessen from 1941, covering a somewhat smaller area

- Gauliga Mitte: covering what is now the federal states of Thuringia and Saxony-Anhalt, split into regional groups in 1944

- Gauliga Mittelrhein: covering the Middle Rhine and Rhineland, then part of Prussia, after 1941 split into the Gauligen of Köln-Aachen and Moselland

- Gauliga Niederrhein: covering the Lower Rhine region

- Gauliga Niedersachsen: covering what is now the federal states of Lower Saxony and Bremen, from 1939 in two regional groups, in 1942 split into the Gauligen Weser-Ems and Südhannover-Braunschweig

- Gauliga Nordmark: covering what is now the federal states of Hamburg and Schleswig-Holstein and the western half of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, in the 1939–40 season split into two groups, from 1942 split into the Gauligen Hamburg, Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg

- Gauliga Ostpreußen: covering the region of East Prussia and the Free City of Danzig, playing in two, from 1935 four regional groups, from 1939 in a single division, including occupied Polish territories, Danzig became part of the Gauliga Danzig-Westpreußen in 1940, folded in 1944

- Gauliga Pommern: covering the region of Pomerania, now divided between Poland and Germany, until 1937 operating in an eastern and a western group, divided again in 1940

- Gauliga Sachsen: covering what is now the federal state of Saxony, in the 1939–40 season divided in two groups, in 1944 divided into seven groups

- Gauliga Schlesien: covering the region of Silesia, in the 1939–40 season divided into two groups, from 1941 subdivided into the Gauligen Niederschlesien and Oberschlesien

- Gauliga Südwest/Mainhessen: covering the Palatinate, Saarland and Mainhessen (Frankfurt) regions, from 1939 in two regional groups, in 1941 subdivided in the Gauligen Hessen-Nassau and Westmark

- Gauliga Westfalen: covering the region of Westphalia, divided into three regional groups in 1944

- Gauliga Württemberg: covering the state of Württemberg, in the 1939–40 season divided into two groups, in 1944 divided into three groups

Gauligen formed through subdivision of existing leagues

- Gauliga Südhannover-Braunschweig: formed when the Gauliga Niedersachsen split in 1942, covering the eastern half of its region, the Gauliga Ost-Hannover split from it in 1943, split into regional groups in 1944

- Gauliga Hamburg: formed when the Gauliga Nordmark was split in 1942

- Gauliga Hessen-Nassau: formed when the Gauliga Südwest/Mainhessen was split in 1941, covering the region now part of the federal state of Hesse

- Gauliga Köln-Aachen: formed when the Gauliga Mittelrhein was split in 1941

- Gauliga Mecklenburg: formed when the Gauliga Nordmark was split in 1942

- Gauliga Moselland: formed when the Gauliga Mittelrhein was split in 1941, played in two regional groups and included clubs from Luxembourg

- Gauliga Niederschlesien: formed when the Gauliga Schlesien was split in 1941, covering the north-western half of the region

- Gauliga Oberschlesien: formed when the Gauliga Schlesien was split in 1941, covering the south-eastern half of the region

- Gauliga Osthannover, split from the Gauliga Südhannover-Braunschweig in 1943

- Gauliga Schleswig-Holstein: formed when the Gauliga Nordmark was split in 1942

- Gauliga Weser-Ems: formed when the Gauliga Niedersachsen split in 1942, covering the western half of its region, split into regional groups from 1943

- Gauliga Westmark: formed when the Gauliga Südwest/Mainhessen was split in 1941, covering the region now part of the federal states of Saarland and Rhineland-Pfalz, also included the FC Metz from the Lorraine region

Gauligen formed after German expansion

- Gauliga Böhmen und Mähren: formed in the occupied parts of what is now the Czech Republic, then called the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, in 1943, two regional groups, only including German clubs, Czech clubs played their own championship

- Gauliga Danzig-Westpreußen: formed in occupied Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia in 1940

- Gauliga Elsaß: formed in the occupied French region of Alsace in 1940, first in two groups, from 1941 in a single division

- Gauliga Generalgouvernement: formed in the occupied Polish provinces which became part of the so-called General Government in 1941, in various numbers of groups

- Gauliga Ostmark: formed in the annexed country of Austria in 1938, in 1941 expanded with northern parts of Yugoslavia and renamed Gauliga Donau-Alpenland

- Gauliga Sudetenland: formed in the predominantly German speaking parts (Sudetenland) of Czechoslovakia annexed in 1938, from 1940 also with German clubs from Prague, in various number of groups

- Gauliga Wartheland: formed in the occupied Reichsgau Wartheland in 1941, first in two groups, from 1942 in a single division

Clubs in the Gauligen from annexed territories

Three of the Gauligen contained clubs from regions occupied and annexed by Germany after the start of the Second World War in 1939.

The Gauliga Elsaß was completely made up of French clubs from Alsace, who had to Germanise their names, like RC Strasbourg, which became Rasen SC Straßburg.

In the Gauliga Westmark three clubs from the French Lorraine region played under their German names:

- FV Metz, was FC Metz

- TSG Saargemünd, from Sarreguemines

- TSG Merlenbach, from Merlebach

In the Gauliga Moselland, clubs from Luxembourg took part in the competition, including:

- FV Stadt Düdelingen, formerly Stade Dudelange

- FK Niederkorn, formerly Progrès Niedercorn

- Moselland Luxemburg, formerly Spora Luxembourg

- SV Düdelingen, formerly US Dudelange

- SV Schwarz-Weiß Esch, formerly Jeunesse d'Esch

- Schwarz-Weiß Wasserbillig, formerly Jeunesse Wasserbillig

In the Gauliga Schlesien, later the Gauliga Oberschlesien, a number of clubs from Poland played under their German names:

- TuS Schwientochlowitz, was Śląsk Świętochłowice

- TuS Lipine, was Naprzód Lipiny

- Germania Königshütte, was AKS Chorzów

- 1. FC Kattowitz, retained its name

- Bismarckhütter SV 99, was Ruch Chorzów

- RSG Myslowitz, from Mysłowice

- Sportfreunde Knurow, from Knurów

- Adler Tarnowitz, from Tarnowskie Góry

- Reichsbahn SG Kattowitz, from Katowice

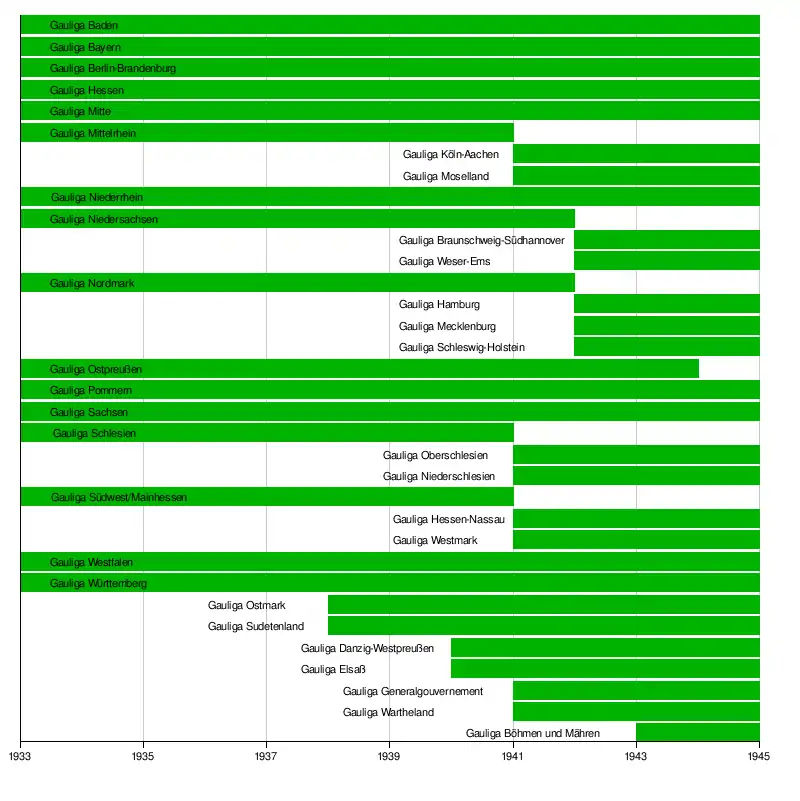

Gauliga timeline

This timeline shows the length of time periods certain Gauligen existed. Note however, that all Gauligen were severely restricted after 1944 and none finished the 1944–45 season. Due to the German military collapse, information on the last season is generally limited, especially in the occupied areas.

See also

- NSRL, the Sports Office of Nazi Germany

- List of Gaue of Nazi Germany

In popular culture

Das große Spiel (The big game), a movie about a fictitious German football team, Gloria 03, directed by Robert Stemmle, released in 1942. The scenes at the final were filmed at the 1941 German championship final Rapid Wien versus FC Schalke 04.[14]

References

- „Fußball ist unser Leben“ – Beobachtungen zu einem Jahrhundert deutschen Spitzenfußballs Archived 2007-08-13 at the Wayback Machine (in German) author: Peter März, publisher: Die Bayerische Landeszentrale, accessed: 24 June 2008

- Sport und Kommerzialisierung: Das Beispiel der Fußballbundesliga (in German) Article on the Bundesliga and its predecessesors, accessed: 20 April 2009

- Karl-Heinz Huba. Fussball Weltgeschichte: Bilder, Daten, Fakten von 1846 bis heute. Copress Sport. (in German)

- Soccer in the Third Reich: 1933–1945. The Abseits Guide to Germany. Accessed 14 May 2008.

- DerErsteZug.com. Fußball Archived 2010-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, by Tait Galbraith. Accessed 15 May 2008

- "Meisterschaft, Pokal, Pflichtspiele", Saale-Zeitung (in German), p. 6, 1933-08-07

- Jewish Teams Worldwide at RSSSF.com. Accessed 15 May 2008.

- German Jews and football history European Jewish Press, 4 July 2006, Accessed 15 May 2008

- Fußball unterm Hakenkreuz – »Wer's trotzdem blieb« – die Austria (in German) author: David Forster and Georg Spitaler, published: 10 March 2008, accessed: 24 June 2008

- „Fußball ist unser Leben“ – Beobachtungen zu einem Jahrhundert deutschen Spitzenfußballs – Juden und Fußball Archived 2007-08-13 at the Wayback Machine (in German) author: Peter März, publisher: Die Bayerische Landeszentrale, accessed: 24 June 2008

- Dietrich Schulze-Marmeling. "Fußball unterm Hakenkreuz". ak – Zeitung für linke Debatte und Praxis. Accessed 15 May 2008. (in German)

- Dirk Bitzer, Bernd Wilting. Stürmen für Deutschland: Die Geschichte des deutschen Fußballs von 1933 bis 1954. Campus Verlag, pp. 60–64. Google Books. Accessed 15 May 2008 (in German).

- Bohemia/Moravia and Slovakia 1938–1944. RSSSF.com. Accessed 31 May 2008.

- Goethe Institut – Das große Spiel accessed: 24 June 2008

Further reading

- Matthias Marschik. "Between Manipulation and Resistance: Viennese Football in the Nazi Era". Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 34, No. 2 (April 1999), pp. 215–229

- Sturmer Fur Hitler : Vom Zusammenspiel Zwischen Fussball Und Nationalsozialismus, by Gerhard Fischer, Ulrich Lindner, Dietrich Schulze-Marmeling, Werner Skrentny, published by Die Werkstatt, ISBN 3-89533-241-0

- Fussball unterm Hakenkreuz, Nils Havemann and Klaus Hildebrand, Campus Verlag, ISBN 3-593-37906-6

External links

- All-time table GERMANY 1st level 1933/34 – 1944/45 by Clas Glenning

- „Fußball ist unser Leben“ – Beobachtungen zu einem Jahrhundert deutschen Spitzenfußballs (in German)

- Das große Spiel – The big game at the Internet Movie Database

- The Gauligen Das Deutsche Fussball Archiv (in German)

- Germany – Championships 1902–1945 at RSSSF.com

- Where's My Country? Article on cross-border movements of football clubs, at RSSSF.com

- Germany – League Final Tables