György Faludy

György Faludy (September 22, 1910 – September 1, 2006; Hungarian pronunciation: [ɟørɟ fɒluɟ]), sometimes anglicized as George Faludy, was a Hungarian poet, writer and translator.

György Faludy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | György Bernát József Leimdörfer September 22, 1910 Budapest, Kingdom of Hungary |

| Died | September 1, 2006 (aged 95) Budapest, Hungary |

| Resting place | Kerepesi Cemetery |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | Hungarian |

| Nationality | Hungarian |

| Citizenship | Hungarian, Canadian |

| Education | Fasori Gimnázium University of Vienna (1928–1930) Humboldt University of Berlin (1930–31) |

| Years active | 1937–2006 |

| Notable works | My Happy Days in Hell Translations of Villon's ballads |

| Notable awards | Kossuth Award |

| Spouse | Zsuzsanna Szegő (1953–1963) Katalin Fatime "Fanni" Kovács (2002–2006) |

| Partner | Eric Johnson (1966–2002) |

| Children | Andrew Faludy |

| Relatives | Alexander Faludy (grandson) |

Life

Travels, vicissitudes, and remembrance

Faludy completed his schooling in the Fasori Evangélikus Gimnázium and studied at the Universities of Vienna, Berlin and Graz.[1] During these times he developed radical liberalist views, which he maintained till the very last days of his life.

In 1938, he left Hungary for Paris because of his Jewish ancestry, and then for the U.S. During World War II, he served in the American forces. He arrived back in Hungary in 1946. In April 1947 he was among a group that destroyed a Budapest statue of Ottokár Prohászka, a Hungarian bishop who is respected by many but who is often considered antisemitic.[2] He only admitted his participation forty years later.

In 1949 he was condemned with fictitious accusations and was sent to the labor camp of Recsk for three years. During this time, he lectured other prisoners in literature, history and philosophy. After his release he made his living by translation. In 1956 (after the Revolution) he escaped again to the West. He settled in London, and was the editor of a Hungarian literary journal.

It was during his stay in London that Faludy wrote his memoir, which was soon translated to English, by which he is still best known outside Hungary: My Happy Days in Hell. (It was only published in his native language in 1987, and since then in several further editions.) He moved to Toronto in 1967 and lived there for twenty years. He gave lectures in Canada and the U.S. and was the editor of Hungarian literary journals. In 1976, he received Canadian citizenship and two years later received an honorary doctorate from the University of Toronto, where he regularly taught. His poems were published by The New York Resident in 1980.

In 1988 Faludy returned to Hungary. After the fall of communism, his works, which had previously been distributed only as samizdat during the Communist period, were at last published in Hungary. New collections of poems appeared in the 1990s, as well as several translations. In 1994 he received Hungary's most prestigious award, the Kossuth Prize. In 2000 he published another memoir, After My Days in Hell, about his life after the labour camp.

Renowned for his anecdotes as well as his writing, he was a celebrated wit whose life story attracted the attention of many foreign authors. Besides the many European authors who visited Faludy, there was the Canadian author George Jonas, screenwriter of Munich, as well as the columnist, poet, and playwright Rory Winston.

Relationships

Faludy's first wife was Vali Ács. His second wife, Zsuzsa Szegő, died in 1963. They had a son, Andrew, born in 1955. Faludy's grandson, Alexander Faludy, born in 1983,[3] is an Anglican priest[4] and a critic[5] of the current government in Hungary.

In 1963 Eric Johnson (1937–2004), a US ballet dancer and later a renowned poet in contemporary Latin poetry, read the memoir My Happy Days in Hell, became enchanted with the author, and traveled to Hungary in search of Faludy. He began to learn Hungarian and finally met Faludy three years later in Malta. He became his secretary, translator, co-author and partner for the next 36 years.[6] In 2002 when Faludy married again, Johnson left for Kathmandu, Nepal, and died there in February 2004.

In 1984, while living in Toronto, Faludy married Leonie Kalman (née Erenyi), a long-time family friend from Budapest and Tangier, Morocco, at Toronto City Hall. George and Leonie kept their separate residences and did not consummate their marriage, but Leonie kept the Faludy name until her death in 2011 (in Fleet, Hants, UK), aged 102.

In 2002, Faludy married a 26-year-old poet, Fanny Kovács. Faludy published poems written jointly with his wife. Even though Faludy was extremely open about his bisexuality, it wasn't revealed to the public until the Hungarian state-owned television broadcast an interview with him after his death.

A memorial park in Toronto

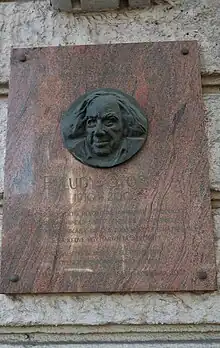

In 2006, a memorial park was built in his honor designed by the landscape architect Scott Torrance, facing his former apartment at 25 St. Mary's Street. It was initiated by the Toronto Legacy Project to commemorate the outstanding cultural figures of the city. A bronze plaque was placed in the park with his portrait, made by the Hungarian-born sculptor Dora de Pedery-Hunt. His poem Michelangelo's Last Prayer, chosen by the poet, was carved on the plaque in English and in Hungarian.[7]

Work

Faludy's translations of the ballads of François Villon, and even more prominent rewritings (as he admitted several times), brought him huge popularity on their initial publication in 1934, and have been since published about forty times. He could have hardly expressed these ideas in any other way in his time. He wrote several volumes of poetry as well, some of which were published in English. His other outstanding success was My Happy Days in Hell (Pokolbéli víg napjaim), a memoir first published in 1962 in English translation, which was translated to French and German as well, but did not appear in the original Hungarian until much later.

Works published in English

- 1962: My Happy Days in Hell; reissued 1985, ISBN 0-00-217461-8; 2003, ISBN 963-206-584-0

- 1966: City of Splintered Gods; translated by Flora Papastavrou

- 1970: Erasmus of Rotterdam. ISBN 0-413-26990-6; 1971, ISBN 0-8128-1444-4

- 1978: East and West: Selected Poems of George Faludy; edited by John Robert Colombo; with a profile of the poet by Barbara Amiel. Toronto: Hounslow Press ISBN 0-88882-025-9

- 1983: George Faludy: Learn This Poem of Mine by Heart: sixty poems and one speech. ISBN 0-88882-060-7; edited by John Robert Colombo

- 1985: George Faludy: Selected Poems 1933-80. ISBN 0-8203-0814-5, ISBN 0-8203-0809-9; edited by Robin Skelton

- 1987: Corpses, Brats, and Cricket Music: Hullák, kamaszok, tücsökzene: poems. ISBN 0-919758-29-0

- 1988: Notes From the Rainforest. ISBN 0-88882-104-2

- 2006: Two for Faludy. ISBN 1-55246-718-X edited by John Robert Colombo

Works published in Hungarian

N.B. Bp. = Budapest

- Jegyzetek az esőerdőből. Budapest. 1991. Magyar Világ Kiadó, 208 p.

- Test és lélek. A világlíra 1400 gyöngyszeme. Műfordítások. Szerk.: Fóti Edit. Ill.: Kass János. Bp. 1988. Magyar Világ, 760 p.

- 200 szonett. Versek. Bp. 1990. Magyar Világ, 208 p.

- Erotikus versek. A világlíra 50 gyöngyszeme. Szerk.: Fóti Edit. Ill.: Karakas András. Bp. 1990. Magyar Világ, 72 p.

- Dobos az éjszakában. Válogatott versek. Szerk.: Fóti Edit. Bp. 1992. Magyar Világ, 320 p.

- Jegyzetek a kor margójára. Publicisztika. Bp. 1994. Magyar Világ, 206 p.

- 100 könnyű szonett. Bp. 1995. Magyar Világ, [lapszám nélkül].

- Versek. Összegyűjtött versek. Bp. 1995. Magyar Világ, 848 p., 2001. Magyar Világ Kiadó 943 p.

- Vitorlán Kekovába. Versek. Bp. 1998. Magyar Világ, 80 p.

- Pokolbeli víg napjaim. Visszaemlékezés.

- Pokolbeli napjaim után. ISBN 963-9075-09-4.

- A Pokol tornácán. ISBN 963-369-945-2.

- Faludy tárlata: Limerickek. Glória kiadó. 2001.

- A forradalom emlékezete (Faludy Zsuzsával közösen). ISBN 963-370-033-7

- Heirich HeineVálogatott versek Faludy György fordításában és Németország Faludy György átköltésében. Egy kötetben. Alexandra Kiadó. 2006.

See also

Archives

There is a George Faludy fonds at Library and Archives Canada.[8] The archival reference number is R10125.[9]

References

- "The phenomenal György Faludy – Hungarian Presence". Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- "Élet és Irodalom". Archived from the original on February 23, 2007. Retrieved September 6, 2006.

- Fabiny, Bishop Tamás (September 24, 2009). "A Lutheran Anglican: Exclusive Interview with the grandson of György Faludy, Alexander Faludy". Archives of the Hungarian Evangelical Church.

- Faludy, Alexander (September 16, 2018). "Laughter in the Face of Absurdity". Hungarian Spectrum.

- Faludy, Alexander (October 5, 2018). "Hungary's slide to authoritarianism". Church Times.

- https://www.thestar.com/comment/columnists/article/96723 Poet's name lives on in parkette, Judy Stoffman, The Toronto Star, Oct 04, 2006

- "Archived copy". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "George Faludy fonds description at Library and Archives Canada". Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- "Finding Aid of George Faludy fonds" (PDF). Retrieved November 14, 2022.

External links

- György Faludy (1910 -), short biography and two poems from European Cultural Review

- György FALUDI (1910-2006) Archived January 13, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, timeline of life and works at HunLit.hu

- Rory Winston, "At Home with homelessness", October 2, 2006, The New York Resident, 2 October 2006

- Albert Tezla, "Faludy György", Hungarian Authors: A bibliographical Handbook, Belknap Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1970. SBN 674 42650 9

- George Jonas, "The poet and the ballet dancer", The National Post, 8 March 2004

- "Interview with the poet Gyorgy Faludy: Literature will not survive the 21st century", hvg.hu, 6 June 2006

- Sandor Peto, Hungarian poet Gyorgy Faludy dies aged 96, Reuters, 2 September 2006

- Gyorgy Faludy, The Economist, 14 September 2006

- "Hungarian poet and translator Gyorgy Faludy dies at 95," International Herald Tribune, September 2, 2006.

- City of Toronto names public space in honour of Hungarian-Canadian poet George Faludy, October 3, 2006

- George Faludy Memorial Park Archived October 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Jewish.hu: Famous Hungarian Jews: György Faludy

- Picture