George Mallory

George Herbert Leigh-Mallory (18 June 1886 – 8 or 9 June 1924) was an English mountaineer who participated in the first three British Mount Everest expeditions from the early to mid-1920s.

George Mallory | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | George Herbert Leigh Mallory 18 June 1886 |

| Died | 8 or 9 June 1924 (aged 37) |

| Cause of death | Mountaineering accident |

| Body discovered | 1 May 1999 |

| Alma mater | Magdalene College, Cambridge |

| Occupation(s) | Teacher, mountaineer |

| Spouse |

Christiana Ruth Turner

(m. 1914) |

| Children |

|

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1915–1918 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | First World War |

| Olympic medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men's Alpinism | ||

| Representing | ||

| Olympic Games | ||

| 1924 Chamonix | Everest expedition | |

Born in Mobberley, Cheshire, Mallory became a student at Winchester College, where a teacher recruited him for an excursion in the Alps, and he developed a strong natural ability for climbing. After graduating from Magdalene College, Cambridge, he taught at Charterhouse School while honing his climbing skills in the Alps and English Lake District. He served in the British Army during the First World War and fought at the Somme.

After the war, Mallory returned to Charterhouse before resigning to participate in the 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition. In 1922, he took part in a second expedition to make the first ascent of the world's highest mountain, in which his team achieved a world altitude record of 27,300 ft (8,321 m) using supplemental oxygen. Once, when asked by a reporter why he wanted to climb Everest, Mallory purportedly replied, "Because it's there."

During the 1924 expedition, Mallory and his climbing partner, Andrew "Sandy" Irvine, disappeared on the Northeast Ridge of Everest. The last sighting of the pair was approximately 800 vertical feet (some 240 metres) from the summit. Mallory's body was discovered and identified 75 years later, on 1 May 1999, by a research expedition that had set out to search for the climbers' remains. Whether Mallory and Irvine reached the summit before they died remains a subject of debate, various theories, and continuing research.

Early life, education, and teaching career

Childhood

George Herbert Leigh-Mallory was born at Newton Hall, Mobberley, Cheshire, on 18 June 1886,[1][2] the first son and second child of the Reverend Herbert Leigh Mallory (1856–1943),[3] rector of the parish.[4][5] His mother was Annie Beridge Leigh-Mallory (née Jebb; 1863–1945),[3][n 1] the posthumous daughter of the Reverend John Beridge Jebb of Walton, Chesterfield, Derbyshire.[4] Mallory had two sisters, Mary Henrietta (1885–1980)[3] and Annie Victoria (Avie) (1887–1989),[3] and a younger brother, Trafford (1892–1944),[3] the Second World War Royal Air Force commander.[7][8][n 2] Mallory's two sisters, Mary Henrietta and Annie Victoria, were also born at Newton Hall.[5] At the end of 1891, the Mallorys moved from Newton Hall to Hobcroft House, Hobcroft Lane, Mobberley, where Mallory's brother Trafford was born.[5] The family resided there until 1904, when they moved to Birkenhead, Cheshire.[11][5] Mallory exhibited an early audaciousness for climbing.[12] At age seven, his first venture into climbing was the roof of his father's church, St Wilfrid's, in Mobberley.[12] His sister Avie recalls, "He climbed everything that it was at all possible to climb."[12] Included in his climbing escapades were the drainpipes of the Mallory family home, Hobcroft House, and the walls that divided the farmers' fields.[12] In 1914, Mallory's father, Herbert Leigh Mallory, adopted the surname Leigh-Mallory by royal licence.[4]

1896–1905: West Kirby, Glengorse, and Winchester College

In 1896, Mallory was sent to Glengorse boarding school in Eastbourne on the south coast of England after the headmaster of his first preparatory school in West Kirby near Birkenhead, died, resulting in its abrupt closure.[13][14][15][16] During the summer of 1900, Mallory won a mathematics scholarship to Winchester College, Hampshire, where he started as a mathematical scholar in September of that year.[17][15] At Winchester, he was proficient at sports, in addition to his academic excellence.[18] In July 1904, Mallory was a member of the Winchester team who won the Ashburton Shield for rifle shooting at Bisley.[18][19]

Robert Lock Graham Irving was a senior master in Mallory's house at Winchester, an accomplished mountaineer and a member of the Alpine Club.[20][21] In 1904, Irving was searching for new climbing companions after the death in an accident of the partner with whom he had done most of his climbing.[20][21] Irving recruited Mallory and his fellow pupil and friend, Harry Olivier Sumner Gibson (1885–1917),[22][n 3] for a trip to the Alps.[23][20][21][24] In early August 1904, Irving, Mallory, and Gibson travelled to the Alps, for Mallory's first foray into high-altitude mountaineering.[23][20] In his final year at Winchester, Mallory studied history instead of mathematics.[25] After sitting his exams, he was awarded a history scholarship to Magdalene College, Cambridge, known as a sizarship.[25]

1905–1909: Magdalene College, Cambridge

In October 1905, at the start of the Michaelmas term, Mallory entered Magdalene College to study history under A. C. Benson, the newly appointed supervisor in history at the college.[26][27][28][29] Through his companions James Strachey and Geoffrey Keynes, Mallory got to know their elder brothers, Lytton Strachey and John Maynard Keynes, who were members of the Bloomsbury Group.[30][31] Through the Stracheys, he met and befriended their cousin, the painter Duncan Grant,[n 4] also a Bloomsbury member.[36][31] Among these friends, particularly Lytton Strachey, his letters attest to a flirtatious, homoerotic, and "explicitly gay" friendship.[37]

Mallory had to consider a future career.[38] In 1907,[39] he had consulted the deputy headmaster of Winchester, Howard Rendall, about the possibility of becoming a teacher there, but Rendall gave him a stern retort;[38] Arthur Benson suggested Mallory return to Magdalene for a fourth year, where he could improve upon his degree.[40] Mallory returned and settled into quarters at Pythagoras House, a short distance from Magdalene College.[41][40][42]

In February 1909, Geoffrey Winthrop Young invited Mallory to Wales for a climbing trip at Easter.[43] After Mallory's return to Magdalene, Young sent him an application form for membership in the Climbers' Club, and in May 1909, Mallory was elected a member.[43]

In June 1909, Mallory received a letter from the headmaster of Winchester College, Hubert Burge, which communicated the possibility of a teaching position opening at Winchester at Easter 1910, in French, German, and mathematics.[44][45][46] He travelled to Winchester and discussed the outlook, but Burge turned him down, explaining that the teaching post required too high a degree of mathematical knowledge for his academic qualifications.[47][48][46] In July 1909, at the end of the term, Mallory's education at Magdalene was complete.[46]

1909–1910: Interim

.jpg.webp)

In October 1909, the painter Simon Bussy, whose wife Dorothy was the sister of Lytton and James Strachey, invited Mallory to spend the winter months with them at their villa in Roquebrune in the Alpes-Maritimes.[49][50] Mallory, who had recently received a small family legacy, accepted their offer and travelled to France in early November to stay with the Bussys.[51][46] He stayed in Paris for one month to improve his French language and linguistic proficiency by reading, attending the theatre and music hall, attending Sorbonne lectures, and conversing.[52][53][54]

In April 1910, Mallory returned to Cambridge, contemplating his future career prospects.[55][56][54] At the beginning of May, he took a temporary teaching post at the Royal Naval College, Dartmouth, which lasted two weeks.[55][57][54] In July 1910, Mallory received a letter from the headmaster of Charterhouse, Gerald Henry Rendall,[n 5] offering a job teaching Latin, mathematics, history, and French.[60][58][59]

Christiana Ruth Turner

Christiana Ruth Turner (1891–1942)[61][62] was the second daughter of architect Hugh Thackeray Turner (1853–1937)[3][n 6] and Mary Elizabeth Turner (née Powell; 1854–1907),[3][64][65][66] who died after developing pneumonia when Ruth was fifteen.[67] Mallory and the Turner family developed a close friendship and he became a regular visitor to their dwelling at Westbrook.[66] On 29 July 1914, six days before Britain entered the First World War, Mallory and Ruth were married in Godalming,[n 7] with Mallory's father performing the ceremony and Geoffrey Winthrop Young acting as best man.[70][71][72] Mallory and Ruth had two daughters and a son: Frances Clare (1915–2001),[73][3][74] Beridge Ruth, known as "Berry" (1917–1953),[75][76] and John (1920–2011).[3][77][78][79]

First World War

Mallory enlisted and started artillery training at Weymouth Camp in January 1916.[80] Frank Fletcher, headmaster of Charterhouse, had initially challenged Mallory's inquiries about enlisting and had asked the government about policies regarding schoolmasters enlisting.[81][82][83] Mallory received additional training at the School of Siege Artillery at Lydd Camp.[84] He arrived in France on 4 May 1916[85] and fought at the Battle of the Somme in the 40th Siege Battery.[86][87] Later that year, he was granted leave,[88][89] spending ten days at Westbrook House with his wife Ruth and daughter Clare before returning to France on Boxing Day.[90]

He was reassigned as an orderly officer, serving as a colonel's assistant at the 30th Heavy Artillery Group headquarters, three miles behind the front line, for the first weeks of 1917.[91][92][89] At the beginning of February 1917, the command recommended Mallory for a staff lieutenancy; he rejected it and was instead assigned a liaison officer position to a French unit.[91][93] At the end of March 1917, he applied to rejoin the 40th Siege Battery, which had moved to a new location.[93] On 7 April 1917, during the prelude to the Battle of Arras, he was back at the front with the 40th Siege Battery in an exposed observation post, directing artillery fire.[89]

"The trenches were in a filthy state, owing to a more or less futile attack made by our men the night before. I don't object to corpses so long as they are fresh. I soon found that I could reason thus with them ... But this is an accepted fact that men are killed ... your jaw hangs and your flesh changes colour and blood oozes from your wounds. With the wounded it is different. It always distresses me to see them."

— George Mallory, in a letter to his wife, Ruth. 15 August 1916.[94][95]

In September 1917 Mallory was sent, under new orders, to Avington Park Camp near Winchester, and he was transferred from the Siege Battery to a Heavy Battery. Mallory then trained at the camp with the Royal Artillery's new generation of 60-pounder heavy guns.[96][97][98]

In October 1917, Mallory was promoted lieutenant and commenced a training course for newly promoted officers at Avington Park Camp.[99][97][100]

On 23 September 1918, after completing a final training course at Newcastle, Mallory was reassigned to the 515th Siege Battery, stationed between Arras and the French coast.[101][102] On the evening of 11 November 1918, at the officers' club in Cambrai, Mallory celebrated peace with his brother Trafford.[101][103][n 8] Due to the British requirement to demobilise more than a million men after the armistice and the dearth of ships that could transport them across the English Channel, Mallory did not return to England until the second week of January 1919.[105][106][n 9]

Post–war

Return to Charterhouse School & resignation

Following his return from France, Mallory and his family re-established themselves in their previous residence, The Holt in Godalming, Surrey.[108][106] At the end of January 1919, Mallory resumed his teaching position at Charterhouse, where he taught English and history.[109][110]

Mallory felt dissatisfied as a schoolmaster, devoting more attention to mountaineering issues, the direction of international politics, and the fundamental objectives of education, and pondering how he could find more time for writing.[111][112]

Resignation from Charterhouse and the lure of Everest

In January 1921, representatives of the Royal Geographical Society and the Alpine Club jointly established the Mount Everest Committee to organise and finance an expedition to Mount Everest.[113][114] The committee consisted of four RGS members and four Alpine Club members; from the RGS were Sir Francis Younghusband, Arthur Robert Hinks, Edward Lygon Somers-Cocks, and Colonel Evan Maclean Jack; from the Alpine Club were Professor John Norman Collie, John Percy Farrar, Charles Francis Meade, and John Edward Caldwell Eaton.[115][116] The committee's primary objective in 1921 was a thorough reconnaissance of the mountain and its approaches to determine the most viable route to the summit, and in 1922 to return for a second expedition, using this route for an all-out attempt to reach the summit.[117] On 23 January 1921, Mallory received written correspondence from John Percy Farrar, secretary of the Alpine Club, its former president and the nascent Mount Everest Committee member.[118] In the letter, Farrar asked Mallory if he would be interested in participating in an expedition to Everest: "It appears an attempt on Everest will occur this summer. The party would depart in early April and return in October. Any ambitions?"[118]

Although grateful for the invitation, Mallory initially felt reluctant to accept it, knowing that his participation would mean a lengthy separation from his wife and young children, and he also expressed scepticism regarding the viability of the expedition.[119][120] Geoffrey Winthrop Young visited him at the Holt, Godalming when he learned of his hesitance and swiftly persuaded him and Ruth not to disregard the opportunity, saying that it would be an incredible adventure and earn him reputable renown for prospects in future professions as an educator or writer.[121][119] Young's arguments convinced Ruth, and she concurred that Mallory should join the expedition; realising it was "the opportunity of a lifetime," Mallory ultimately decided to participate.[120] On 9 February 1921, in Mayfair, London, Mallory met with Sir Francis Younghusband, chairman of the Mount Everest Committee; John Percy Farrar, a committee member; and Harold Raeburn, the assigned mountaineering leader of the 1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition.[122][120] At the meeting, Younghusband formally invited Mallory to join the expedition and was surprised to observe that he accepted without any evident emotion and exhibited no indication that he was brimming with enthusiasm.[123][120] In February 1921, Mallory officially tendered his resignation from his mastership at Charterhouse, changing his previous intended decision of resigning at the end of the summer term.[120]

On 8 April 1921, Mallory departed from the Port of Tilbury in Essex, England, on board SS Sardinia, and brought the final shipment of expedition supplies.[124][125] It was a solitary voyage, as the other expedition members had theretofore departed or were already in India.[126]

Climbing in Europe

In England

Mallory's first rock climbing experience in England transpired during a nine-day excursion to the Lake District in September 1908 with Geoffrey Keynes, Harry Olivier Sumner Gibson, and Harold Edward Lionel Porter (1886–1973),[127] where they took lodgings at Wasdale Head.[128][129] Mallory and Keynes climbed together predominantly, while Gibson and Porter joined them on some climbs.[130] Their initial climb was Kern Knotts Crack on Great Gable.[131] The following day they climbed Napes Needle, the famous rock pinnacle on Great Gable, at 55.77 ft (17 m), graded Very Difficult.[128][132] Also on Great Gable, they climbed Eagle's Nest Ridge Direct, graded Mild Very Severe.[128][132]

They accomplished a successful ascent of North Climb on Pillar Rock,[130] graded Hard Difficult.[133][134]

On 21 September 1908, they claimed two new routes on the Ennerdale face of Great Gable:[130] Mallory's Left-Hand Route, at 98.43 ft (30 m), graded Very Difficult, and Mallory's Right-Hand Route, at 121.4 ft (37 m), graded Mild Very Severe.[128][135][136] In August 1913,[137] Mallory and Geoffrey Winthrop Young achieved a new route, Pinnacle Traverse, at 196.9 ft (60 m), graded Difficult, on the crag, Carn Lés Boel, in Cornwall, England.[138][139] On 7 September 1913, Mallory and Alan Goodfellow, a Charterhouse student, created Mallory's Variation, a new route on Abbey Buttress, Great Gable, where Mallory finished the route by ascending a twenty-foot slab on tenuous grips, rather than exiting to the right.[140][141] On 8 September 1913, with Mallory leading Goodfellow, the pair established another new route, this time on the West Face of Low Man, Pillar Rock, at 213.3 ft (65 m), and graded Hard Very Severe, which they named North-West by West and now known as Mallory's Route.[140][142] Compared to Mallory's Route, Conrad Anker rated the Second Step on Mount Everest at 5.10, using the Yosemite Decimal System.[143]

In Scotland

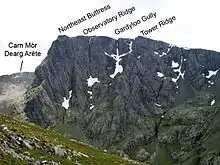

On 6 April 1906, Mallory, Irving, and Leach reached the summit of Ben Nevis,[n 10] climbing in snow via Observatory Gully and Tower Gully on the mountain's northeast face.[146] The following day, 7 April 1906, the trio ascended Stob Bàn, following the corniced main arête to the summit.[147] On 9 April 1906, they climbed to the summit of Càrn Mòr Dearg, which preceded a second successful ascent of Ben Nevis on the same day via North Trident Buttress.[148] On 10 April 1906, they successfully climbed a feature on Ben Nevis—that they termed East Zmutt Ridge after the Zmutt Ridge on the Matterhorn—that was most presumably Ledge Route on Number Five Gully Buttress, rated Grade II and first ascended in 1895.[149] On 12 April 1906, Mallory, Irving, and Leach undertook the last climb of their trip, attaining a successful ascent of Ben Nevis in snow and ice via North-East Buttress, now rated Grade IV.[150] Their achievement was the second recorded winter ascent of this route, the first by Willie Naismith, Alexander Kennedy, William Wickham King, Frances Conradi Squance, and Walter Brunskill on 3 April 1896.[149][151] On 28 July 1918, Mallory, David Randall Pye, and Leslie Garnet Shadbolt (1883–1973),[152] climbing together, made a new route on the North Face of Sgùrr a' Mhadaidh on the Isle of Skye, Scotland.[153][154] On 31 July 1918, the triad established another new route with Mallory leading on the Western Buttress of the crag, Sron na Ciche, located in the Cuillin mountains on the Isle of Skye, Scotland; this route is now known as Mallory's Slab and Groove, and graded Very Difficult.[155][156][157] On 1 August 1918, Mallory and Ruth left the Isle of Skye, while Pye and Shadbolt remained, creating a new route on 5 August 1918 on Sron na Ciche, named Crack of Doom, and graded Hard Severe.[158][159][160]

In Wales

On 14 September 1907, Mallory accomplished his first two climbs in Wales: North Gully on Tryfan, first ascended by Roderick Williams and his brother Tom in 1888;[161] and North Buttress, also on Tryfan, first climbed by Owen Glynne Jones, George Dixon Abraham, and Ashley Perry Abraham at Easter 1899.[162][163][164] On 18 September 1907,[162] Mallory, Keynes, and Wilson climbed Terminal Arête, graded Moderate, on Lliwedd's East Buttress, first ascended in 1903,[165] and purportedly inadvertently dislodged a large rock as they were finishing their climb.[166][167] Much to their consternation, the rock narrowly missed James Merriman Archer Thomson and his partner E.S. Reynolds as they climbed below on a new route, which they aptly named Avalanche Route.[168][169]

On Craig yr Ysfa, the triad climbed two routes: Great Gully, at 731.6 ft (223 m), graded Very Difficult and first climbed by James Merriman Archer Thomson, R.I. Simey, and W.G. Clay on 22 April 1900;[170][171] and Amphitheatre Buttress, at 961.3 ft (293 m), graded Very Difficult, with the first ascent completed by George Dixon Abraham, Ashley Perry Abraham, Darwin Leighton, and James William Puttrell in 1905.[162][172] Mallory returned to Snowdonia in August 1908, accompanied by his younger brother, Trafford.[173]

During the same month on this trip, Mallory, climbing solo, established the first ascent of The Slab Climb on East Buttress of Lliwedd,[174] now known as Mallory's Slab, at 220.0 ft (67.056 m), and graded Very Difficult.[173][175] The ascent of The Slab Climb, allegedly occurred due to Mallory scaling it to retrieve his pipe, which he had left behind, on a ledge known as Bowling Green.[176]

In April 1909, Mallory and Geoffrey Winthrop Young journeyed to Pen-y-Pass for a climbing trip, a week before the main party of climbers, who stayed at the Gorphwysfa Hotel, where Mallory and Young joined them after camping for a week in a corrugated-iron outbuilding, which they called the shanty.[177] On the cliffs of Craig yr Ysfa, Mallory and Young established three new ascents and climbed The Slab Climb (Mallory's Slab) on East Buttress of Lliwedd, which Young described as "The hardest rocks I have done."[177]

In early September 1911, Mallory and his sister Mary travelled to Wales, joined by Harold Edward Lionel Porter, Mallory's climbing partner, for a week-long excursion, and stayed at the Snowdon Ranger Inn, situated on the shore of Llyn Cwellyn.[178][179] During this trip, Mallory and Porter pioneered several new routes that elevated Mallory to the pinnacle of modern British climbing.[180] On Y Garn, with Porter leading Mallory on the climb's crux, they ascended a new route, now known as Mallory's Ridge, at 393.7 ft (120 m), now graded Hard Very Severe.[180][181] This route defeated James Merriman Archer Thomson in 1910, who abandoned his attempt on the most challenging pitch, a sixty-foot segment of vertical rock.[180]

Alps

Mallory embarked on several expeditions in the Alps. His first climb was in 1904. However, there, Mallory and climbing companion Harry Gibson suffered from altitude sickness.[182][183]

In January 1905, Robert Lock Graham Irving established the Winchester Ice Club.[25] With Irving as the club's president, Mallory, Harry Olivier Sumner Gibson, Harry Edmund Guise Tyndale (1888–1948),[184] and Guy Henry Bullock became members.[185] In August 1905, the Ice Club travelled to the Alps.[25]

Mallory would not return to the Alps for another four years, where they climbed Unterbächhorn via the Enkel Ridge, and reached the summit.[186] Their objective was to ascend the formidable, unclimbed Southeast Ridge of Nesthorn.[187]

At the beginning of August 1911, Mallory returned to the Alps with Robert Lock Graham Irving and Harry Edmund Guise Tyndale.[188] Within the Graian Alps, they ascended Gran Paradiso on 8 August.[189][190][191] Later, on 9 August, they reached the summit of Herbétet by way of a first ascent of its Western Ridge.[190][192]

In August 1912, Mallory undertook his sixth expedition to the Alps, along with mountaineering partners Harold Edward Lionel Porter and Hugh Rose Pope (1889–1912).[193][n 11] On 8 August 1912, Mallory, Porter, and Pope ascended to the summit of Pointe des Genevois.[197]

On 2 August 1919, Mallory and Porter set out from Montanvert and proceeded up the Mer de Glace to the Glacier de Trélaporte, from where they ascended a new route to the summit of Aiguille des Grands Charmoz.[198][199]

Climbing in Asia

1921 British Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition

Mallory participated in the first historical expedition to Mount Everest in 1921, which was coordinated and subsidised by the Mount Everest Committee and had the express objective of undertaking a detailed reconnaissance of the mountain and its approaches to discover the most accessible route to its summit.[114] From the Survey of India, expedition surveyors Henry Morshead and Oliver Wheeler, with the assistance of Indian surveyors Lalbir Singh Thapa, Gujjar Singh, and Turubaz Khan, produced the first accurate maps of the Mount Everest region.[203][204][205] On a 1⁄4 -inch scale, the expedition surveyed 12,000 square miles (31,080 km2) of new territory, and they also revised an existing 1⁄4 -inch scale, 4,000 square miles (10,360 km2) map of Sikkim.[206][207] Using photo-topographical surveying instruments, Major Wheeler single-handedly completed a methodical and detailed photographic survey of the environs of Mount Everest, covering an area of 600 square miles (1,554 km2) on a 1-inch scale.[208][207] From the Geological Survey of India, expedition geologist Alexander Heron conducted a geological reconnaissance by mapping an area of 8,000 square miles (20,720 km2) on a 1⁄4 -inch scale.[209][210] The area's natural history was explored in considerable detail by expedition naturalist and medical officer Sandy Wollaston, with mammals, birds, and plants collected, including new specimens.[211][207] On 18 August 1921, at 3:00 a.m., after an arduous two-month-long reconnaissance of Everest's northern and eastern approaches, Mallory, Guy Bullock, Henry Morshead, and a porter named Nyima left their high camp at approximately 20,000 ft (6,096 m).[212][213] From the western head of the Kharta Glacier, they ascended to the col of Lhakpa La, at 22,470 ft (6,849 m), which they reached at 1:15 p.m.[213][214] From the col of Lhakpa La, 1,200 ft (366 m) directly below them, was the head of the East Rongbuk Glacier, across which rises a 1,000 ft (305 m) wall of snow and ice leading to Everest's North Col, at 23,031 ft (7,020 m), from where mountaineers can attain the summit via the North Col-North Ridge-Northeast Ridge route.[213][215] Their preliminary reconnaissance was complete; they discovered the gateway to the mountain.[213][216] On 23 September 1921, at 11:30 a.m., Mallory, Bullock, Wheeler, and ten porters left their camp on Lhakpa La, descended into the East Rongbuk Glacier, and pitched camp at approximately 4:00 p.m., at an elevation of 22,000 ft (6,706 m),[217] 1 mile (1.6 km) from the beginning of the ascent to the North Col.[218][219][220] On 24 September 1921, at 7:00 a.m., the three expedition members and three porters, Ang Pasang, Lagay, and Gorang, departed from their camp, traversed 1 mile (1.6 km) across the East Rongbuk Glacier to the foot of the 1,000 ft (305 m) precipitous wall of snow and ice, which they arduously ascended, and reached the North Col at 11:30 a.m.[218][219][221] On the col and above, gale force winds blew from the northwest, which made further advance impossible, and they descended to their camp on the East Rongbuk Glacier, where they spent the night.[222] Wheeler suffered from the first stages of frostbite in each of his lower extremities below the knee, and Bullock was exhausted.[223][224] The next day, 25 September 1921, the severe winds had not abated; the porters were at the limits of their physical reserves, and Mallory made a definitive decision by ending the reconnaissance and expedition.[225][226][227]

1922 British Mount Everest expedition

First summit attempt, Mallory, Somervell, Norton, and Morshead

In 1922, Mallory returned to the Himalayas as a member of the 1922 British Mount Everest expedition led by Brigadier-General Charles Bruce.[233] The expedition's primary objective was to attain the summit of Mount Everest and become the first mountaineers to accomplish this.[234] On 20 May 1922, at 7:30 a.m., Mallory, Howard Somervell, Edward Norton, Henry Morshead, and four porters began their day at Camp IV, situated on the North Col at an elevation of 23,000 ft (7,010 m).[235][236] At 8:00 a.m., after getting roped up, the eight men commenced their ascent from the North Col without supplemental oxygen.[237][238] They aimed to climb the North Ridge and establish Camp V at an altitude of 26,000 ft (7,925 m), from where they planned an attempt to reach the summit.[239][240] At 11:30 a.m., they attained an elevation of 25,000 ft (7,620 m), a gain of 2,000 ft (610 m) from the North Col, in 3+1⁄2 hours, a vertical climbing rate of 571 ft (174 m) per hour, including stops.[241] Mallory estimated that from their present position, it would necessitate an approximate three hours to ascend 1,000 ft (305 m) and pitch Camp V there, which left little time for the porters to return to Camp IV on the North Col before nightfall and was uncertain of finding a well-sheltered area from the strong winds on the lee-side of the North Ridge above them.[242][243] Therefore, they abandoned their initial plan and erected Camp V at their current altitude of 25,000 ft (7,620 m).[242][243] The four porters departed for the North Col camp at 3:00 p.m., and Mallory, Somervell, Norton, and Morshead spent the night at Camp V.[244][245]

The next day, 21 May 1922, at 8:00 a.m., the four mountaineers were roped up and commenced their attempt to reach the summit from Camp V.[246] After a few steps, Morshead, who was suffering from frostbite in his fingers and toes, declared that he was unable to continue and stayed behind at Camp V.[242][247] Adverse weather conditions prevented the climbers from beginning their ascent at 6:00 a.m. as planned, leaving them decidedly behind schedule.[248] Other than possible mountaineering difficulties, the fate of their summit bid depended predominantly on time and speed.[249] Mallory's arithmetical computation estimated their vertical ascent rate at an unsatisfactory 400 ft (122 m) per hour, not including stops, from which it was apparent they would be climbing after nightfall, a risk they were unwilling to take, and decided that 2:30 p.m. was their retreat time.[250] At 2:15 p.m., Mallory, Somervell, and Norton halted and lay against rocks on the North Ridge, where they remained for fifteen minutes and nourished their weary bodies with sustenance.[251] Their aneroid barometer read 26,800 ft (8,169 m), a height later rectified and confirmed by a theodolite as 26,985 ft (8,225 m), a new world altitude record.[252] At 2:30 p.m., they began their descent, and at 4:00 p.m., they reached Camp V, where Morshead was waiting to join them for the return to Camp IV on the North Col.[253][254] The four climbers roped up and recommenced their descent to 23,000 ft (7,010 m).[254] As they descended, Morshead, who was third on the rope, slipped, and his impetus dragged Somervell and Norton down a slope leading directly to the East Rongbuk Glacier, several thousand feet below.[253][255] Mallory, who was leading at the time of this incident, immediately reacted by forcing the pick of his ice axe into the snow and hitching the climbing rope around the axe's adze.[255] He stood in a secure position and held the rope in his right hand above the hitch, pressed downward with his left hand on the axe's shaft, and, using his entire weight, leaned towards the incline, securing the pick of his axe in the snow.[255] Commonly, in such circumstances, the belay will not hold when applying this technique, or the climbing rope will snap.[256] Fortunately, the axe and rope held because their bodies' combined weight and momentum did not come upon the rope at once, which saved the lives of Somervell, Norton, and Morshead.[256][257] They regained their positions and reached their tents after nightfall at 11:30 p.m. on the North Col., exhausted, hungry, frostbitten, and dehydrated.[258][259][260]

Second summit attempt, Finch and Bruce

On 27 May 1922, at 6:30 a.m., George Finch, Geoffrey Bruce, and Tejbir Bura departed from Camp VI at 25,500 ft (7,772 m) on the North Ridge, using supplemental oxygen for the expedition's second attempt to reach the summit of Everest.[261] Their plan of assault was to take Bura, who was shouldering two spare oxygen cylinders, as far as the Northeast Shoulder at 27,400 ft (8,352 m), where he would begin his descent, leaving Finch and Bruce to continue their ascent.[262] When they reached 26,000 ft (7,925 m), Bura, at the limits of his endurance, collapsed, unable to continue.[263] He commenced his descent to Camp VI, where, being a solitary figure, he would await the return of his two climbing partners.[264] Finch and Bruce continued their endeavour to reach the summit, loaded up the extra oxygen cylinders that Bura had been shouldering, and dispensed their climbing rope to enable themselves to advance faster.[265] By the time they attained an elevation of 26,500 ft (8,077 m) on the North Ridge, the wind, which had been gradually increasing, had intensified to such a strength that it necessitated a change in their line of ascent, which they hoped would reduce the possibility of the onset of exposure by providing more shelter.[265] Therefore, Finch and Bruce left the North Ridge and continued their climb towards the summit by traversing across the Yellow Band on the North Face of Everest.[265] When they reached 27,000 ft (8,230 m), they changed course and climbed diagonally towards a point on the Northeast Ridge, approximately halfway between the Northeast Shoulder and the summit.[230] Not long after, Bruce, about 20 ft (6 m) below Finch when his oxygen apparatus failed, struggled valiantly upwards as his climbing partner came to his aid, and they soon repaired the equipment.[230] The time was approximately midday, and their aneroid barometer registered an elevation of 27,300 ft (8,321 m), surpassing the previous attempt by 315 ft (96 m), a new world altitude record.[266][267] Weakened by hunger and debilitated by exhaustion, they were not in any physical condition to continue their summit bid.[268] They began their descent, regained the North Ridge just after 2:00 p.m. and reached Camp VI at 2:30 p.m.[269]

Third summit attempt, Mallory, Somervell, Crawford, and the North Col avalanche

At the beginning of June 1922 the expedition arranged a third attempt to reach the summit.[270] The plan was to ascend to their old Camp V at 25,000 ft (7,620 m) without using supplemental oxygen and then, using a cylinder of oxygen each, continue to an elevation of 26,000 ft (7,925 m) where they would establish the new Camp V. From there the team would use the supplemental oxygen for the attempt to reach the summit.[271] On 7 June 1922 at 8:00 a.m., Mallory, Somervell, Colin Crawford, and fourteen porters left Camp III at 21,000 ft (6,401 m) and traversed the head of the East Rongbuk Glacier. The team reached the base of the 1,000 ft (305 m) wall of snow and ice rising to the North Col at 10:00 a.m.[272] and 15 minutes later Somervell, Mallory, Crawford, and one of the porters began the climb.[273] At 1:30 p.m. the group halted about 600 ft (183 m) below Camp IV to allow time for the other porters to join them.[274][275][276] At about 1:50 p.m., soon after the team continued the ascent, an avalanche began on an ice cliff above them and swept over the entire group.[277][274][278] Somervell, Mallory, Crawford, and the porter managed to dig out from beneath the snow[279] and saw a group of four porters approximately 150 ft (46 m) below them[274][280] gesturing down the slope. The avalanche had swept the other nine porters into a crevasse.[274][281] The remaining team members, later joined by expedition members John Noel and Arthur Wakefield, immediately began a search and rescue effort,[282][283] eventually finding eight of the nine porters. Only two had survived.[282] A memorial cairn was constructed at Camp III[284] in honour of the seven porters who perished: Lhakpa, Narbu, Pasang, Pema, Sange, Temba, and Antarge.[285][286] This marked the end of the third summit attempt and the 1922 British Mount Everest expedition.[287]

Mallory's last climb

1924 British Mount Everest expedition

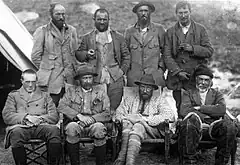

The personnel of the expedition

Mallory participated in the 1924 British Mount Everest expedition, led again, as in 1922, by Brigadier-General Charles Bruce.[288] The other members of the 1924 expedition team were: Edward Norton as second-in-command and mountaineering leader; mountaineers Andrew Irvine, Howard Somervell, Geoffrey Bruce, Bentley Beetham, and John de Vars Hazard; mountaineer and oxygen officer Noel Odell; photographer and cinematographer John Noel; naturalist and medical officer Richard Hingston; and transportation officer Edward Shebbeare.[289][290][288] On 9 April 1924, General Bruce collapsed due to recurrent malaria and had ongoing cardiovascular issues during the trek to Everest Base Camp.[291][292] As a result, Norton took charge of the expedition leadership, appointed Mallory as deputy and mountaineering leader, and General Bruce returned to India.[293][294]

First summit attempt, Mallory and Bruce

On 1 June 1924, at 6:00 a.m., Mallory and Bruce, without supplemental oxygen on the expedition's first summit attempt, and eight porters commenced their ascent from Camp IV on the North Col at 23,000 ft (7,010 m).[295][296] They planned to climb the North Ridge and establish Camp V at approximately 25,500 ft (7,772 m), where they would sleep overnight; the following day, 2 June 1924, they would ascend to about 27,200 ft (8,291 m), where they would pitch Camp VI, sleep there overnight, and from there, on 3 June 1924, attempt to reach the summit, without oxygen.[297][298] The precise elevation for establishing Camps V and VI depended on the porters' physical abilities to carry heavy loads in the rarefied air and weather conditions.[298] As the two climbers and eight porters ascended the North Ridge with an average gradient of 45 degrees, they exposed themselves to a penetrating northwest wind.[299] At approximately 25,000 ft (7,620 m), four of the porters could not ascend any further after reaching the limits of their endurance.[299] Mallory, Bruce, and the four remaining porters progressed to an elevation of 25,200 ft (7,681 m), where they established Camp V.[295][300] Five of the eight porters descended to Camp IV, leaving three to shoulder loads the following day up to the location where the expedition intended to pitch Camp VI.[301] Mallory, Bruce, and the three porters slept at Camp V that night, and on the next day, 2 June 1924, only one porter was able to proceed, and two declared themselves sick and physically unable to carry loads.[301] Without enough porters to assist both climbers, the summit attempt, destined to fail, was abandoned immediately, and the party returned to the North Col, which they reached by midday.[302][301]

Second summit attempt, Somervell and Norton

On 2 June 1924, at 6:30 a.m., Somervell and Norton began their summit attempt from Camp IV, without supplemental oxygen, along with the assistance of six porters carrying loads.[303] During their ascent on the North Ridge, they encountered Mallory, Bruce, and their porters descending from Camp V after their summit bid, which proved unavailing.[304] Because Camp V, part of which the previous party had intended to use for their higher Camp VI, had been left where it was, in its entirety, with tents and sleeping bags, Somervell and Norton sent a pair of their porters down, who descended with Mallory, Bruce, and their porters, as they no longer required their services or the loads that they were shouldering.[305] At approximately 1:00 p.m., Somervell, Norton, and their four porters reached Camp V at 25,200 ft (7,681 m), which the preceding party had pitched on the sheltered eastern side of the North Ridge.[305] The two mountaineers and their four porters spent the night at Camp V.[306] On the following morning of 3 June 1924, one of their porters, Lobsang Tashi, suffering from altitude sickness, could not continue and descended alone to Camp IV on the North Col.[307] At 9:00 a.m., Somervell, Norton, and their three remaining porters, Narbu Yishé, Llakpa Chédé, and Semchumbi, departed from Camp V and continued their ascent up the North Ridge.[308] At approximately 1:30 p.m., the valiant Semchumbi, who was lame with a swollen knee, had reached his limits and could not continue.[309] As a result, Norton brought the entire party to a halt at about this time, and he selected a site to pitch Camp VI at their current altitude.[310] At an elevation of 26,700 ft (8,138 m), they established Camp VI in a narrow cleft, which provided some possible shelter from the northwest wind.[310][232] At about 2:30 p.m., the services of the three porters, Narbu Yishé, Llakpa Chédé and Semchumbi, were no longer required, and Norton sent them down to Camp IV on the North Col.[310] Somervell and Norton camped that night at 26,700 ft (8,138 m), the highest elevation at which anyone had ever slept up to that time.[311]

On 4 June 1924, at 6:40 a.m., Somervell and Norton left Camp VI and commenced their assault to reach the summit of Mount Everest, a vertical height of 2,331.7 ft (710.7 m) above.[311] The weather conditions were fine—clear, almost windless, but bitterly cold—a perfect day for a summit attempt.[312] After approximately an hour of ascent up the North Ridge, they reached the lower edge of the Yellow Band, a stratum of sandstone about 1,000 ft (305 m) deep that crosses the entire North Face.[311] From this location, they changed their line of ascent by leaving the North Ridge and traversing diagonally across the Yellow Band, following a line roughly parallel to and approximately 500 ft (152 m) to 600 ft (183 m) lower than the crest of the Northeast Ridge.[313] Towards midday, Somervell and Norton reached a point below and in proximity to the top periphery of the Yellow Band and were a short distance east of the Norton Couloir.[314] At midday, as they neared 28,000 ft (8,534 m), Somervell, who was suffering from an extremely sore throat and a severe cough as a result, felt that, from his perspective, it was impracticable for him to continue.[315][316] To Norton, he expressed that he was only delaying him and encouraged him to continue alone and reach the summit.[317][318] Somervell sat on a ledge while Norton proceeded solo.[318] At 1:00 p.m., suffering from temporary visual impairment due to oxygen deficiency,[n 15] exhausted from his efforts, and knowing that from his present location and the current time, he stood no chance of reaching the summit and returning safely, Norton retreated from a point where he had attained a new world altitude record of 28,126.0 ft (8,572.8 m).[320][n 16] During their descent on the North Ridge, at around 25,000 ft (7,620 m), Somervell experienced intense coughing and dislodged something in his throat, severely obstructing his breathing.[325] He was close to death and saved his own life by forcibly pressing on his chest with both hands, dislodging the obstruction that came into his mouth, and coughing up blood.[325] The obstruction was a slough from the mucous membrane lining of his larynx caused by frostbite.[325] At 9:30 p.m., Somervell and Norton reached Camp IV on the North Col.[326]

Third summit attempt, Mallory and Irvine

On 4 June 1924, at 2:10 p.m., Mallory and Andrew Irvine, using supplemental oxygen for the final half of their ascent, left Camp III at 21,000 ft (6,401 m) and reached Camp IV on the North Col at 23,000 ft (7,010 m) in 3 hours, at 5:10 p.m., including approximately 1⁄2 an hour at a dump choosing and testing oxygen cylinders.[327][328][329] That night at Camp IV, Mallory shared a tent with Norton, who had just returned from his summit attempt with Somervell, and informed Norton that if his summit bid with Somervell had failed, he had planned to make one further attempt with supplemental oxygen.[330] Mallory further elucidated that he went down to Camp III and recruited enough porters with Bruce's assistance for another endeavour.[330] He also chose Irvine as his climbing partner because of the initiative and mechanical expertise he exhibited with the oxygen apparatus.[331] On 6 June 1924, at 8:40 a.m., Mallory and Irvine, who would use supplemental oxygen for part of their ascent, set off in excellent weather from Camp IV on the North Col for Camp V on the North Ridge at 25,200 ft (7,681 m), accompanied by eight porters.[332][333][334] Both mountaineers shouldered modified oxygen apparatus, each man carrying two cylinders apiece, and their eight porters, not using oxygen, took provisions, bedding, and extra oxygen cylinders.[333][335] Mallory and Irvine progressed steadily and attained Camp V in good time, and shortly after 5:00 p.m. that evening, four of their porters arrived back at Camp IV, with a note from the climbing party stating, "There is no wind here, and things look hopeful."[332][333] The two climbers and their four remaining porters spent the night at Camp V.[333] On 7 June 1924, Mallory, Irvine, both using oxygen for part of their climb, and their four porters ascended to Camp VI at 26,700 ft (8,138 m) on the North Ridge.[332][333] That same day, expedition member Noel Odell, in support of Mallory and Irvine and his porter Nema climbed to Camp V from the North Col.[336][334] Soon after they had attained Camp V, Mallory and Irvine's four remaining porters reached Camp V from Camp VI, and they gave Odell a handwritten note from Mallory, which read:[337]

Dear Odell,

"We're awfully sorry to have left things in such a mess—our Unna Cooker rolled down the slope at the last moment. Be sure of getting back to IV to-morrow in time to evacuate by dark, as I hope to. In the tent I must have left a compass—for the Lord's sake rescue it: we are here without. To here on 90 atmospheres for the 2 days—we'll probably go on 2 cylinders—but it's a bloody load for climbing. Perfect weather for the job!"

Odell's porter, Nema, was suffering from altitude sickness, so consequently, that evening of 7 June 1924, he sent him down, along with the other four porters, to Camp IV.[339][334] When the five porters reached Camp IV on the North Col, one of them, known as Lakpa, gave expedition member John Noel a second handwritten note from Mallory, which read:[340]

Dear Noel,

"We'll probably start early tomorrow (8th) in order to have clear weather. It won't be too early to start looking for us either crossing the rock band under the pyramid or going up skyline at 8.0 P.M."

John Noel's filming location was above Camp III, on the ledge of a buttress at 22,000 ft (6,706 m) on the Eastern Ridge of Changtse, which he called "Eagle's Nest Point."[342] From this vantage point, Noel had a clear view across the head of the East Rongbuk Glacier, the ice slope leading to the North Col, the Northeast Ridge, and the North Face of Mount Everest.[342] Lakpa the porter who had given Noel the note informed him that Mallory and Irvine were in good health, had reached Camp VI, and that the weather was fine.[340] The message from Mallory reminded Noel of the locations and the approximate time of where and when to look for him and Irvine during their summit attempt, which they had previously discussed and organised.[343] Mallory erroneously wrote 8:00 p.m. on Noel's note; he meant 8:00 a.m.[344]

The following morning, 8 June 1924, at 8:00 a.m., after spending the night alone at Camp V, Odell, again supporting Mallory and Irvine, commenced his ascent up to Camp VI and, on his way, intended to conduct a geological study.[345] That same morning, Noel perched himself at "Eagle's Nest Point," where he directed the long lens of his motion picture camera towards the summit pyramid of Mount Everest to film Mallory and Irvine.[346] He had two assistant porters, peering through a telescope in turns, who saw nothing; 8:00 a.m. arrived and went by without sighting the two mountaineers, and by 10:00 a.m., cloud and mist had enshrouded their view of the entire summit ridge.[344] As Odell ascended to Camp VI, in a limestone band at approximately 25,500 ft (7,772 m), he discovered the first definite fossils on Mount Everest.[334] When he reached an elevation of about 26,000 ft (7,925 m), Odell climbed a small crag close to 100 ft (30.48 m) in height, and above him, as he reached its top at 12:50 p.m., he witnessed a rapid clearing of the atmosphere and consequently saw the entire summit ridge and final peak of Mount Everest revealed, and he sighted Mallory and Irvine on a prominent rock step on the ridge:[347]

"At 12:50, just after I had emerged in a state of jubilation at finding the first definite fossils on Everest, there was a sudden clearing of the atmosphere, and the entire summit ridge and final peak of Everest were unveiled. My eyes became fixed on one tiny black spot, silhouetted on a small snow crest beneath a rock step in the ridge, and the black spot moved. Another black spot became apparent and moved up the snow to join the other on the crest. The first then approached the crest rock step and shortly emerged at the top. The second did likewise. Then the whole fascinating vision vanished, enveloped in cloud once more. There was but one explanation. It was Mallory and his companion, moving, as I could see even at that great distance, with considerable alacrity ... The place on the ridge mentioned is a prominent rock step at a very short distance from the base of the final pyramid."

— Noel Odell, support climber and last man to see Mallory and Irvine alive, 8 June 1924. This version of Odell's sighting appeared in the Aberdeen Press and Journal on 5 July 1924.[348]

The location of Odell's initial reported final sighting of Mallory and Irvine—before they disappeared into the clouds and was to become the last time the pair were seen alive—was at the top of the Second Step and determined by expedition member John de Vars Hazard using a theodolite to be at an elevation of 28,227 ft (8,603.5 m).[349][350][n 17] At approximately 2:00 p.m., as Odell reached Camp VI at 26,700 ft (8,138 m), snow began to fall, and the wind strengthened.[353] Inside Mallory and Irvine's tent, he discovered spare clothes, food scraps, sleeping bags, oxygen cylinders, and parts of the oxygen apparatus; outside, he found additional parts of the oxygen apparatus and the duralumin carriers.[353] They left no note specifying when they had commenced their summit attempt or what might have transpired to create a delay.[354] Odell departed from Camp VI, ascended about 200 ft (61 m) in the direction of the summit in sleet and poor visibility of no more than a few yards, and whistled and yodelled in an attempt to direct Mallory and Irvine towards Camp VI in case they happened to be within hearing distance, but it was to no avail.[354] Within one hour, he retreated, and at approximately 4:00 p.m., as he re-attained Camp VI, the weather cleared; the entire North Face became bathed in glorious rays of sunshine, and the upper crags became visually observable, but there was no sign of either Mallory or Irvine.[354] Odell left Mallory's compass, which he had retrieved from Camp V, inside the tent at Camp VI and, at about 4:30 p.m., began his descent to Camp IV on the North Col, which he reached at 6:45 p.m.[355]

On the morning of 9 June 1924, Odell and Hazard thoroughly inspected Camps V and VI using binoculars, with no sign of either mountaineer.[356][357] At 12:15 p.m., Odell and two porters, Nima Tundrup and Mingma, left Camp IV and, at 3:30 p.m., reached Camp V, where they spent the night.[358][359] The following morning, 10 June 1924, he sent his two porters back to Camp IV, as they were indisposed and unable to ascend with him to Camp VI.[360] In a strong, bitter westerly wind, Odell climbed alone to Camp VI, using supplemental oxygen for part of the way, to about 26,000 ft (7,925 m), before disuse.[361] At Camp VI, which he reached soon after 11:00 a.m., it became immediately apparent that Mallory and Irvine had not returned to camp, as everything was as he had left it two days previously.[362][363] Odell discarded his oxygen apparatus and forthwith set off along the presumed route, which both climbers might have taken, to search within the limited time available to him.[363] After trudging on for almost two hours with no sign of either Mallory or Irvine, he ascertained that the likelihood of finding them was remote in the broad expanse of crags and slabs, and a more extensive search towards the final pyramid necessitated a larger party.[363] Odell returned to Camp VI at 26,700 ft (8,138 m), and after taking shelter for a short time from the relentlessly strong wind, he hauled two sleeping bags from the tent up to a precipitous snow-patch, where he positioned the bags in the shape of a T, communicating the signal that there was no trace of either Mallory or Irvine.[364] At 2:10 p.m., Hazard, 3,700 ft (1,128 m) below at Camp IV on the North Col, saw the T-shaped signal and knew what it meant, as he and Odell had previously drawn up a code of signals before Odell had left the North Col on 9 June 1924, for Camp V.[365][366][367] At approximately 2:15 p.m., Hazard placed six blankets in the shape of a cross on the snow surface at the North Col, which relayed a signal of death, to the watchers at Camp III.[365][366][368] Expedition member John Noel was the first to see the signal through his telescope from Camp III, at the head of the East Rongbuk Glacier.[366] After being informed about the situation, expedition leader Edward Norton ordered a response sign for Hazard on the North Col.[369] Richard Hingston positioned three lines of blankets arranged apart on the glacier a short distance beyond Camp III, conveying the message, "Abandon hope and come down."[369] After retrieving Mallory's compass and an oxygen apparatus at Camp VI, Odell descended to Camp IV, which he reached shortly after 5:00 p.m.[370]

On 8 June 1924, the same day that Mallory and Irvine were last seen alive by Odell, Mallory's wife Ruth and their three children were on holiday in Bacton, Norfolk.[365] On 13 and 14 June 1924, Howard Somervell and Bentley Beetham oversaw the carving and building of a memorial cairn at Base Camp in memory of those who perished in the 1921, 1922, and 1924 British Mount Everest expeditions, with the inscription: In Memory Of Three Everest Expeditions; 1921, Kellas; 1922, Lhakpa, Narbu, Pasang, Pema, Sange, Temba, Antarge; 1924, Mallory, Irvine, Shamsher, Manbahadur.[371][285][372] On 15 June 1924, the expedition evacuated Base Camp for the journey home.[373] On 19 June 1924, Arthur Robert Hinks, who was then in London, received a coded telegram that read, "Mallory Irvine Nove Remainder Alcedo," sent from expedition leader Edward Norton. "Nove" expressed the message that Mallory and Irvine had died, and "Alcedo" meant that everyone else was unharmed.[365] That same day, Hinks sent a telegram to Cambridge, where shortly after 7:30 p.m. that evening, a delivery boy arrived with it at the Mallory residence, Herschel House, Herschel Road, Cambridge, to communicate the tragic news and the condolences of the Mount Everest Committee to Mallory's wife, Ruth.[374]

Message from the King and memorial service at St Paul's Cathedral

On 24 June 1924, a message sent from King George V to Sir Francis Younghusband of the Mount Everest Committee appeared in The Times, in which the King requested to convey "an expression of his sincere sympathy" to the families and committee concerning the tragic deaths of the "two gallant explorers," Mallory and Irvine.[375] On 17 October 1924, a solemn memorial service at St Paul's Cathedral, London, was held in honour of the two climbers, at which the presiding, Right Reverend Henry Paget, the Bishop of Chester, from whose diocese both men had come, delivered the sermon.[376] The other clergy present included the Archdeacon of London Ernest Holmes, Canon William Newbolt, and Canon Simpson.[377] The parents of both mountaineers, the widow of the deceased, Mrs Christiana Ruth Leigh-Mallory, their relatives and close friends, members of the 1921, 1922, and 1924 Everest expeditions, members of the Mount Everest Committee, the Alpine Club, the Royal Geographical Society, and several other distinguished explorers and scientists also attended.[377] Additionally present were representatives of the royal family; Sir Sidney Robert Greville represented the King; Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Piers Walter Legh, the Prince of Wales; Lieutenant Colin Buist, the Duke of York; Lieutenant-Colonel Douglas Gordon, the Duke of Connaught; and Major Eric Henry Bonham, Prince Arthur of Connaught.[378][377]

Mallory's will was proven in London on 17 December; he bequeathed his estate of £1706 17s. 6d. (roughly equivalent to £103,517 in 2021[379]) to his wife.[380]

Lost on Everest for 75 years

Discovery of the ice axe, 1933

On 30 May 1933, at 5:40 a.m., during the 1933 British Mount Everest expedition, Percy Wyn-Harris and Lawrence Wager commenced their summit attempt from Camp VI, at 27,495 ft (8,380.4 m), on the Yellow Band, below the Northeast Ridge.[381][382] After approximately one hour of climbing, Wyn-Harris, who was leading, found an ice axe located about 60 ft (18 m) below the crest of the Northeast Ridge and some 751 ft (229 m) east of and below the First Step, at an elevation of 27,723 ft (8,450 m).[383][384] Wyn-Harris and Wager left the ice axe exactly where the former had discovered it, and after retreating from a failed summit attempt where they had reached approximately the same place as Edward Norton in 1924, at 28,126.0 ft (8,572.8 m), Wyn-Harris retrieved the ice axe and presumably left his own in its place.[385][386][n 18] The ice axe, discovered, was positively ascertained to be a possession of either Mallory's or Irvine's, to the exclusion of all others.[388]

During his descent with Edward Norton on 4 June 1924, Howard Somervell dropped his ice axe in the Yellow Band near the Norton Couloir,[n 19] further west from where Wyn-Harris had found the ice axe, and no mountaineers from the Everest expeditions before 1933, other than Mallory and Irvine, were at the location where Wyn-Harris discovered the ice axe.[389][390] Although it is definitive that the ice axe found by Wyn-Harris was, in fact, Mallory's or Irvine's, there was no decisive evidence to prove which mountaineer owned the axe after its discovery.[391] In 1934, Noel Odell inspected the ice axe when it was shown to him by Wyn-Harris and saw three parallel horizontal nick marks on its shaft, which he learned neither Harris nor Wager had seen.[391][390] He thought it might have been a mark used by Irvine on some of his equipment, although not verified by visual inspection of such items returned to Irvine's family, some of whom seemed to remember seeing a similar marking.[391]

Mallory's widow Ruth informed Odell that, "as far as she was aware"—which may indicate she was not entirely sure—Mallory never marked his equipment with triple marks or any other type of mark and assumed it most probable the axe belonged to Irvine.[391] To Odell, Wyn Harris suggested that a porter may have cut the triple mark on the axe of the shaft to identify his masters' property during the 1924 expedition, though such was not the practice of many, if any, of the 1924 porters.[391] Wyn Harris assured Odell that his porter Pugla cut the X mark, seen lower down on the shaft of the axe found in 1933, during the return journey from the 1933 expedition.[391] A number of the 1933 British Mount Everest expedition members considered it likely that the ice axe belonged to Mallory because it had Swiss manufacturers, Willisch of Täsch, stamped upon it, and Mallory had journeyed to the Alps a short time before the 1924 expedition, when he may have acquired it.[391] They were unaware that this manufacturer had supplied all members of the 1924 expedition with light axes and that Mallory or Irvine might have used them during their fatal summit attempt.[391] In 1962, a brother of Andrew Irvine found a military swagger stick, which is presumed to have belonged to Irvine, and upon it are three horizontal identification nick marks resembling those on the ice axe discovered by Wyn-Harris in 1933; therefore, the axe is possibly Irvine's, but it is inconclusive.[390][392]

In July 1977, Walt Unsworth, author of Everest: The Ultimate Book of the Ultimate Mountain, examined the ice axe discovered in 1933 and observed four sets of marks on its shaft.[393] On the axe's shaft, in addition to the three parallel horizontal nick marks seen by Odell and the cross mark cut by Pugla, he saw a single horizontal nick mark above the three observed by Odell and another three nick marks, though fainter in appearance, on the other side of the shaft opposite the cross mark.[393]

Frank Smythe's sighting, 1936

In 1937, Frank Smythe wrote a letter to Edward Norton in reply to Norton's approbation of Smythe's book Camp Six, an account of the 1933 British Mount Everest expedition.[394] Among other things mentioned in his letter was the discovery by Wyn-Harris of the ice axe in 1933 found below the crest of the Northeast Ridge, where Smythe felt certain it marked the scene of an accident to Mallory and Irvine in 1924.[395][396] Also in the letter, Smythe disclosed to Norton that during the 1936 British Mount Everest expedition, he scanned the North Face of Everest with a high-powered telescope from Base Camp and spotted an object, which he presumed was the body of either Mallory or Irvine and that it was not to be written about because he feared press sensationalism:[397][396]

"Since my search for the two Oxford fellows, I feel convinced that it marks the scene of an accident to Mallory and Irvine. There is something else ... it's not to be written about, as the press would make an unpleasant sensation. I was scanning the face from the Base camp through a high-power telescope last year[1936] when I saw something queer in a gully below the scree shelf ... it was a long way away and very small ... but I've a six/six eyesight, and I do not believe it was a rock ... when searching for the Oxford men on Mont Blanc, we looked down onto a boulder-strewn glacier and saw something which wasn't a rock either—it proved to be two bodies. The object was at precisely the point where Mallory and Irvine would have fallen had they rolled on over the scree slopes below the yellow band. I think it is highly probable that we shall find further evidence next year."

— Frank Smyth, in a letter to Edward Norton, 4 September 1937.[398][394]

Smythe's sighting was unknown to the public until his son Tony revealed the information in his book, My Father, Frank: Unresting Spirit of Everest, released in 2013; the author discovered a copy of the letter that his father had written to Norton in the back of a diary.[399]

Tom Holzel, Mount Everest historian

Everest historian, German-American Thomas Martin Holzel, the co-author with Audrey Salkeld of The Mystery of Mallory and Irvine, first became interested in the Mallory and Irvine mountaineering enigma after reading a brief reference about the subject in a 1970 edition of The New Yorker.[400] Holzel devised a theory regarding the Mallory and Irvine mystery, initially published in the 1971 September edition of Mountain magazine.[401] His theory was that the two mountaineers split up soon after Noel Odell had sighted them ascending the Second Step at 12:50 p.m., and when successfully climbed, each had only 1+1⁄2 hours of supplemental oxygen remaining, not sufficient for both men to reach the summit in two or three hours from that location.[402] Holzel argued that given this dilemma, Mallory took Irvine's oxygen equipment, belayed him down the Second Step, from where he descended towards Camp VI at 26,700 ft (8,138 m), and with the additional oxygen, Mallory recommenced the attempt to reach the summit alone.[403] He further surmised that as the exhausted Irvine descended after parting with Mallory shortly after 1:00 p.m., the "rather severe blizzard" described by Noel Odell,[404] which lasted from approximately 2:00 p.m. until 4:00 p.m.,[405] covered the mountain with snow, turned his descent into a deadly endeavour, and caused him to slip and fall to his death.[403][406] Holzel added that Mallory presumably reached the summit in the late afternoon, and during his descent, darkness prevented him from descending the Second Step; left with no alternative, he bivouacked and froze to death overnight.[406] He also theorised that where the ice axe was found—presumably the scene of an accident—by Percy Wyn-Harris in 1933, a body tumbling down the North Face from the area of its discovery would come to a halt on a snow terrace below at approximately 26,903 ft (8,200 m).[403]

On 14 February 1980, Holzel received a letter dated 7 February 1980 from Hiroyuki Suzuki, foreign secretary of the Japanese Alpine Club.[407] Suzuki's letter was in reply to Holzel, who had written to the Japanese inquiring about their 1979 Sino-Japanese Mount Everest reconnaissance expedition and requesting that they look out for Irvine's body—which Holzel had prognosticated might be discovered on a snow terrace at about 26,903 ft (8,200 m)—and the camera he may have carried.[408] The letter from Suzuki contained grievous news and unexpected information.[409] He expressed that on 12 October 1979, at 2:12 p.m., as their reconnoitring party attempted to reach the North Col, an avalanche occurred at an elevation of 22,474 ft (6,850 m) that swept three Chinese, Wang Hongbao, Nima Thaxi, and Lou Lan, into a crevasse, resulting in their deaths.[409][410][411] In the latter part of the letter, Suzuki told Holzel that on 11 October 1979—the day before the avalanche caused his death—Hongbao informed their expedition climbing leader, Japanese Ryoten Hasegawa, that during the 1975 Chinese Mount Everest expedition, he had seen "two deads."[409][412] One of them he had seen close to a side moraine in the East Rongbuk Glacier below the 1975 expedition Camp III, and the other was on the Northeast Ridge route at an altitude of 26,575 ft (8,100 m).[409][412][413] Suzuki further expressed in the letter that Hongbao was a non-English speaker but repeated the word "English, English" to Hasegawa.[409][412] Suzuki added that the first was possibly Maurice Wilson, questioned who the second he saw at 26,575 ft (8,100 m) was, and informed Holzel that Hongbao touched the latter's torn clothes, some of which the wind had blown away, and he buried the corpse by placing snow on it.[409][412][n 20]

The 1986 Mount Everest North Face Research Expedition

On 25 August 1986, the Mount Everest North Face Research Expedition (MENFREE), which Holzel instigated, congregated at Mount Everest's North Base Camp in Tibet.[417] The expedition aimed to resolve the enigma surrounding Mallory and Irvine's disappearance on 8 June 1924.[417] Their primary objective was to ascend to the 27,000 ft (8,230 m) snow terrace, where they intended to locate the remains of the "English dead" Wang Hongbao had sighted during the 1975 Chinese Mount Everest expedition.[418] They assumed that if found, the cameras both mountaineers may have carried would resolve the 62-year-old mystery of whether or not they attained the summit before they died.[418] Their secondary objective was to search the area immediately above the Second Step, where they hoped to discover Mallory and Irvine's empty oxygen cylinders, proving that they had reached that elevation and thus possibly gained the summit.[418] The expedition leader was Andrew Harvard, and the other members were Tom Holzel, Audrey Salkeld, David Breashears, Ken Bailey, Mary Kay Brewster, David Cheeseman, Catherine Cullinane, Sue Giller, Alistair Macdonald, Al Read, Steve Shea, David Swanson, Roger Vernon, Mike Weis, Jed Williamson, Mike Yager, and a team of fifteen Sherpas led by Nawang Yonden.[419] They successfully established Camp V on the North Ridge at an elevation of 25,500 ft (7,772 m) but were hampered by snowstorms and avalanches, which prevented them from reaching 27,500 ft (8,382 m), where they had planned to establish Camp VI, from which they intended to search for the bodies of Mallory and Irvine.[420][421][422] Despite the adverse weather and snow conditions, they discovered two oxygen cylinders from the 1922 British Mount Everest expedition.[421] On 17 October 1986, nine days before the expedition retreated from Mount Everest, one of their team, Sherpa Dawa Nuru, perished in an avalanche below the North Col.[423][422]

During the Mount Everest North Face Research Expedition, their liaison officer, Zhiyi Song, also a 1975 Chinese Mount Everest expedition member, on which Wang Hongbao had presumably seen "two deads," informed Holzel that he heard about Hongbao's story and declared, "None of it is true. Wang never reported finding an English mountaineer."[424] Holzel asked Song if it was conceivable that Hongbao had discovered an English body and suggested that perhaps he did not officially report it and only informed his friends.[424] Song knowledgeably replied, "If that is so," he knew who Hongbao's mountaineering partners were in 1975 and that Holzel could meet them on the return journey to Peking, China.[424] In Lhasa, Tibet, after the cessation of the Mount Everest North Face Research Expedition, Song introduced Holzel to Chen Tianliang, Hongboa's 1975 group climbing leader.[425] During the interview with Holzel, Tianliang denied that Hongbao had discovered an English body at 26,575 ft (8,100 m) in 1975 and asserted that he would know because he was with Hongbao the entire time they were at high altitudes on Everest.[425] Tianliang was positive that if Hongbao had come across mortal remains, it must have only been those of a missing Chinese mountaineer whom Tianliang was assigned to search for and who was located a few days later by expedition members.[425] As the interview continued, Tianliang agreed with Holzel that Hongbao could not have found the remains of the missing Chinese climber because he would have identified and reported his find immediately.[425] As their conversation neared its conclusion, Holzel asked Tianliang if there were anything he would like to add, and Tianliang declared that during a rest period at Camp VI,[n 21] he received a radio call instructing him to ascend to Camp VII to search for the missing climber.[425] Tianliang and a Tibetan porter left Camp VI and ascended to Camp VII to search, leaving two remaining climbers at Camp VI, Wang Hongbao and Zhang Junyan.[425] Holzel asked Tianliang did he think it possible that Hongbao might have found an English body's mortal remains after he and his porter departed for Camp VII, and Tianliang conceded that it was conceivable and added that Zhang Junyan now resided in Peking.[425] Zhiyi Song, the research expeditions' liaison officer, arranged a meeting for Holzel in Peking with Zhang Junyan.[427] At the interview, through his interpreter, Holzel questioned Junyan about what had occurred at Camp VI after Tianliang and his porter left to search for the missing Chinese climber.[428] Junyan stated that he remained in his sleeping bag, and Hongbao exited the tent to go for a walk; he was gone for approximately twenty minutes, and later, as they descended, Hongbao informed him that during his walk, he had discovered the remains of a foreign mountaineer and that Hongbao had also mentioned this to a few additional climbers.[428][n 22]

The 1999 Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition

The 1999 Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition was funded jointly by WGBH/Boston's Nova series and the BBC.[431] The Seattle-based Internet site MountainZone, sponsored by Lincoln LS, also provided daily expedition dispatches on their website.[432][433] The expeditions' other sponsors were Mountain Hardwear, Outdoor Research, Lowe Alpine, Eureka!, Starbucks, PowerBar, Vasque Footwear, Slumberjack, and Glazer's Camera.[434][435] The expedition personnel were Eric Simonson, mountaineer and expedition leader; mountaineer and high-altitude cameraman Dave Hahn; and mountaineer and assistant film producer Graham Hoyland.[434][436] Mountaineers Conrad Anker, Jake Norton, Tap Richards, and Andy Politz.[434][436] Mountaineering historian, researcher, and support climber Jochen Hemmleb; mountaineering historian, researcher, and expedition organiser Larry Johnson; and expedition doctor Lee Meyers.[437][436] High-altitude cameraman Thom Pollard; film producers Liesl Clark and Peter Firstbrook; film sound technician Jyoti Lal Rana;[434][436] photographer Ned Johnston; and a team of twelve Sherpas led by Sirdar Dawa Nuru.[436][438] The expedition's objective was to search for evidence of the 1924 British Mount Everest expedition and to obtain information about the high point attained by Mallory and Irvine, which may have either supported or refuted whether or not they reached the summit.[436][439]

After he had re-examined the historical record of Mount Everest North Face expeditions, Jochen Hemmleb recognised that the only seemingly factual information about Mallory and Irvine—other than artefacts such as the ice axe, found in 1933—was that during the 1975 Chinese Mount Everest expedition, Wang Hongbao had discovered a body that he had intransigently expressed as "English, English!" during what he asserted was a brief twenty-minute walk from Camp VI.[440] The initial challenge was to identify the location of the 1975 Chinese Camp VI and use it as the centre point of a circular search zone with a twenty-minute walk or more, if necessary, radius.[441][442] From a photograph of the 1975 Camp VI, published in the book Another Ascent of the World's Highest Peak—Qomolangma, Hemmleb predictably determined that the Camp was on an ill-defined rib of rock that bisects the snow terrace on the North Face.[441] On 1 May 1999, at approximately 10:00 a.m., Anker, Hahn, Norton, Politz, and Richards reached 26,900 ft (8,199 m), where they were to establish Camp VI.[443] From there, the five mountaineers set out at 10:30 a.m. for the "ill-defined rib" identified in Hemmleb's search guidelines and traversed west over the North Face's precipitously angled terrain.[444][442] Anker searched on intuition and descended to the lower margin of the snow terrace, where it drops away approximately 6,562 ft (2,000 m) to the head of the central Rongbuk Glacier and soon after zig-zagging back up the slope in the direction of Camp VI, he looked to the west and saw a "patch of white," which he proceeded towards, and ascertained that it was an old body; it was 11:45 a.m., and 26,760 ft (8,156 m) was the elevation where the corpse lay.[445][446][447] The body was partially frozen into the scree and well preserved due to the cold, dry air and constant freezing temperatures; it was lying prone, fully extended, with both arms somewhat outstretched and the head pointed uphill.[448][449][450] The right leg had broken, and the left leg was crossed over it, possibly for protection, suggesting the mountaineer was still consciously aware after coming to rest.[451][452] The rear of the body was predominantly exposed, as the clothing had been partially destroyed by the elements and blown away by the wind.[451][453] The exposed skin was bleached white, and although the corpse was frozen, purportedly, some elasticity remained in the frozen tissue; the hands and forearms appeared dark.[451][454] Despite the body being notably intact, Everest's alpine choughs had damaged the right leg, the buttocks, and the abdominal cavity by pecking at them and consuming most of the internal organs.[455][456] Tied to the corpse's waist were the remnants of a braided cotton climbing rope, some tangled around the body, from which its broken, frayed end trailed.[455][457] On the right foot was an intact green leather hobnailed boot; only the tongue of the left boot remained, jammed between the left foot's bare toes and the heel of the right boot.[452][458]

The prevalent assumption was that Irvine had fallen in 1924 from where, in 1933, Percy Wyn-Harris had discovered the ice axe, presumably Irvine's; therefore, Anker, Hahn, Norton, and Richards expected the body to be his, but Politz said, "This is not him."[459][n 23] When they found the remains, before they touched them and determined who it was, they documented photographically and cinematographically both the body and the discovery site.[461][456] Richards, an archaeologist by training, and Norton carefully separated the remaining layers of tattered garments, protected somewhat from the elements that still covered part of the body: multiple layers of cotton, silk underwear, a flannel shirt, woollen pullover and pants, and an outer garment that resembled canvas.[462] Close to the nape of the neck, Norton turned over part of the shirt collar and found affixed to it a clothing label with red print, reading, "W.F. Paine, 72 High Street, Godalming," and below it a second label, again with red print, reading, "G. Mallory."[463] They discovered another label with "G. Leigh. Ma," written in black, and a third label.[463] The expedition members realised, to their surprise, that they had not found Irvine as expected but had discovered the remains of Mallory.[464][449] Because the corpse had frozen into the surrounding scree, the mountaineers used their ice axes and pocketknives to excavate the site to find crucial artefacts and, most importantly, Somervell's Vest Pocket Kodak camera that he "allegedly" had lent to Mallory for his summit attempt with Irvine.[465][466] Presumably, if they had discovered the camera, it might have solved the mystery of whether or not the summit of Mount Everest was reached for the first time in 1924, twenty-nine years before the first confirmed successful ascent of the world's highest peak by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay on 29 May 1953.[467][468] Experts from Eastman Kodak Company have said that it might be possible to develop images from the camera's film using sophisticated techniques and have drawn up specific professional guidelines for an expedition that might discover the camera.[467][469][470]

The injuries on Mallory's body were severe; above the hobnail boot on his right foot, both the tibia and fibula of his right leg—which lay at a grotesque angle—were broken.[455][457] His right scapula was somewhat deformed, and his right elbow was fractured or dislocated.[457] Along his right side were multiple still-noticeable cuts, bruises, and abrasions; on his torso, his ribs had fractured, and black and blue bruises were visible on his chest's skin.[455][452] The broken climbing rope, which had been looped around his waist and secured with a bowline knot, had severely crushed his ribs and burned his skin; the indentation marks caused by the rope tugging on his skin were still observable around his torso; undoubtedly, he had fallen.[455][471] The rope-jerk injuries around Mallory's torso indicate that he and Irvine were roped to each other when the accident occurred; the exact circumstances surrounding their deaths are unknown.[471][457]