Georgian nationalism

Georgian nationalism is a form of nationalism which argues for promotion of Georgian national identity and a nation state based on it.

The beginning of Georgian nationalism can be traced to the middle of the 19th century, when Georgia was part of the Russian Empire. Georgian nationalism evolved from its culture-focused roots in the Imperial Russian and Soviet periods, into a radically ethnocentric form in the late 1980s and early post-Soviet period, before taking on a more inclusive and civic form in the mid-2000s. However, vestiges of ethnic nationalism remain among many Georgians.[1]

Emergence

While the notion of Georgian exceptionalism can be traced back to the middle ages (as demonstrated by the writings of John Zosimus), modern Georgian nationalism emerged in the middle of the 19th century as a reaction to the Russian annexation of fragmented Georgian polities, which terminated their precarious independence, but brought to the Georgians unity under a single authority, relative peace and stability. The first to inspire national revival were aristocratic poets, whose romanticist writings were imbued with patriotic laments. After a series of ill-fated attempts at revolt, especially, after the failed coup plot of 1832, the Georgian elites reconciled with the Russian rule, while their calls for national awakening were rechanneled through cultural efforts. In the 1860s, the new generation of Georgian intellectuals, educated at Russian universities and exposed to European ideas, promoted national culture against assimilation by the Imperial center. Led by the literati such as Ilia Chavchavadze, their program attained more nationalistic colors as the nobility declined and capitalism progressed, further stimulated by the rule of the Russian bureaucracy and economic and demographic dominance of the Armenian middle class in the capital city of Tbilisi. Chavchavadze prominently founded "Land Bank" of Tbilisi, with the aim of protecting Georgian land from being sold off by poor Georgian nobles to rich Armenian bourgeoisie. He also created slogan "Language, Homeland, Religion", which served as a motto of Georgian nationalism. Chavchavadze and his associates called for the unity of all Georgians and put national interests above class and provincial divisions. Their vision did not envisage an outright revolt for independence, but demanded autonomy within the reformed Russian Empire, with greater cultural freedom, promotion of the Georgian language, and support for Georgian educational institutions and the national church, whose independence had been suppressed by the Russian government.[2]

Despite their advocacy of ethnic culture and demographic grievances over Russian and Armenian dominance in Georgia's urban centers, a program of the early Georgian nationalists was inclusive and preferred non-confrontational approach to inter-ethnic issues. Some of them, such as Niko Nikoladze, envisaged the creation of a free, decentralized, and self-governing federation of the Caucasian peoples based on the principle of ethnically proportional representation.[3]

The idea of Caucasian federation within the reformed Russian state was also voiced by the ideologues of Georgian social democracy, who came to dominate Georgian political landscape by the closing years of the 19th century. Initially, the Georgian Social Democrats were opposed to nationalism and viewed it as a rival ideology, but they remained proponents of self-determination.[4] In the words of the historian Stephen F. Jones, "it was socialism in Georgian colors with priority given to the defense of national culture."[5] The Georgian social-democrats were very active in all-Russian socialist movement and after its split in 1905 sided with the Menshevik faction adhering to relatively liberal ideas of their Western European colleagues.[6]

First Georgian republic

.svg.png.webp)

The Bolshevik revolution of 1917 was perceived by the Georgian Mensheviks, led by Noe Zhordania, as a breach of links between Russia and Europe.[6] When they declared Georgia an independent democratic republic on 26 May 1918, they viewed the move as a tragic inevitability against the background of unfolding geopolitical realities.[6]

As the new state faced a series of domestic and international challenges, the internationalist Social-Democratic leadership became more focused on narrower national problems.[7][8] With this reorientation to a form of nationalism, the Georgian republic became a "nationalist/socialist hybrid."[5] The government's efforts to make education and administration more Georgian drew protests from ethnic minorities, further exacerbated by economic hardship and exploited for their political ends by the Bolsheviks who promoted the export of revolution. The government's response to dissent, including among the ethnic minorities, such as the Abkhaz and Ossetians, was frequently violent and excessive. The decision to resort to military solutions was driven by security concerns rather than readiness to settle ethnic scores.[9] Overall, the Georgian Mensheviks did not turn to authoritarianism and terror.[10] However, the events of that time played an important role in reinforcing stereotypes on all involved sides in the latter-day ethnic conflicts in Georgia.[11][12] In the First Republic there were several nationalist parties, the most influential of which was the National Democratic Party.[13]

Soviet Georgia

After the sovietization of Georgia in 1921, followed by suppression of an armed rebellion against the new regime in 1924, many leading nationalist intellectuals went in exile in Europe. In the Soviet Union, Georgian nationalism went underground or was rechanneled into cultural pursuits, becoming focused on the issues of language, promotion of education, protection of old monuments, literature, film, and sports. Any open manifestation of local nationalism was repressed by the Soviet state, but it did provide cultural frameworks and, as part of its policy of korenizatsiya, helped institutionalize the Georgians as a "titular nationality" in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.[14][15] Works of writers such as Mukhran Machavariani, Murman Lebanidze and others, were imbued with strongly nationalist themes. By maintaining the focus of Georgian nationalism on cultural issues, the Soviet regime was able to prevent it from becoming a political movement until the 1980s perestroika period.[15]

The late 1970s saw a re-emergence of Georgian nationalism that clashed with Soviet power. Plans to revise the status of Georgian as the official language of Soviet Georgia were drawn up in the Kremlin in early 1978, but after stiff and unprecedented public resistance the Soviet central government abandoned the plans. At the same time, it also abandoned similar revision plans for the official languages in the Armenian and Azerbaijani SSRs.

Georgian nationalism was eventually more tolerated during the waning years of the USSR due to Mikhail Gorbachev's Glasnost policy. The Soviet government attempted to counter the Georgian independence movement with promises of greater decentralisation from Moscow.

In 1980s, Georgian nationalism became a mass movement focused on independence. Many nationalist movements have arisen during this time. Most of them were focused on contemporary issues, such as demographic decline of ethnic Georgians, growing anti-Georgian and separatist sentiments among ethnic minorities and Soviet affirmative action policies, which were believed to be discriminatory towards Georgians and unjustly beneficial to the ethnic minorities. According to the 1979 Soviet Census, ethnic Georgians made up 68.8% of population in Soviet Georgia. Ethnic Georgians were outnumbered and weakly represented in peripheral districts: Kvemo Kartli, and Samtskhe–Javakheti in the south, in the South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast, and in the Abkhazian ASSR (where Georgians were a plurality), which was a cause of concern. Anti-Georgian riots in Abkhazia and South Ossetia intensified fears that with separation from the Soviet Union, Georgia's ethnic minorities would seek to dismember Georgian territory. The so-called Lykhny Assembly was held on March 18, 1989, when several thousand Abkhaz demanded secession from Georgia. In response, the anti-Soviet nationalist groups organized a series of unsanctioned meetings across Georgia, claiming that the Soviet government was using Abkhaz separatism in order to oppose the Georgia's pro-independence movement. The demonstration in Tbilisi was suppressed by the Soviet Army, which finally diminished Georgians' trust towards the Soviet system and paved the path to the independence.

Demographic situation was a particular cause of concern with immigration of non-Georgian ethnicities being thought to be encouraged by Soviet authorities. In parallel, ethnic Georgian population experienced demographic decline, while non-Georgian population was booming and often harboured anti-Georgian sentiment. This caused fears that such trends would lead to non-Georgian ethnicities outnumbering ethnic Georgians in their own country and that Georgian ethnicity would eventually become extinct. Immigration of non-Georgians was believed to be encouraged by the Soviet government with a goal of artificially bumping up ethnically non-Georgian population and using it to create ethnic conflicts and obstruct Georgia's path towards independence. In 1989, a letter of Georgian writer Revaz Mishveladze was published in Young Communist newspaper, which discussed demographic issues. It read:

Georgia is on the verge of a real disaster – extinction…. We have to increase the proportion of the Georgians at all costs (today it is 65%). Georgia can tolerate no more than 5% of guests

Zviad Gamsakhurdia and other Georgian nationalists saw Georgian nation as a historically forged community with ancient rights over its homeland. In the rhetoric of Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Georgians, as a native population on Georgian soil, have intrinsic rights to be regarded as titular and dominant nation, while non-Georgians are "guests" who should not overstay their welcome. In a speech in the Georgian region of Kakheti, Gamsakhurdia said:

Kakheti has always been a very demographically pure region, where the Georgian element has always predominated and always wielded power. Now things have taken shape there in such a way that we are wondering how to save Kakheti. Tatardom is rearing its head there and measuring its strength against Kakheti, there are Leks in one place, Armenians in another, Ossetians in a third place, and they are on the point of swallowing up Kakheti. This was done to us by these communists, these traitors. They sold our beloved, holy land for money. Kakheti, the homeland of our heroes, this homeland of saints was sold, sold to foreign seeds, and today we are facing a catastrophe.

Revival of religion

The re-emergence of Georgian nationalism coincided with the revival of the Georgian Orthodox Church, which returned to its conservative roots, proselytizing Georgian orthodoxy as the national creed. The church showed its solidarity with the national movement, and the most of the parties of the national movement ascribed the church a special national role. Georgian nationalists identified ethnicity and religion (orthodox Christianity) as primary markers of the Georgian national identity, a fact which was described by scholars as ethno-religious nationalism. In 1987, the Georgian Orthodox Church canonized Illia Chavchavadze as Saint Ilia the Righteous (წმინდა ილია მართალი, tsminda ilia martali). According to philosopher Giga Zedania, this was a starting point from which the emerging ethno-religious nationalism defined itself as the successor of Georgian nationalism of the nineteenth century. Illia Chavchavadze’s motto "Language, Homeland, Religion" served as a source for legitimizing the Orthodox Christianity as the dominant religion. During a clerical ceremony in 1988, Georgian Patriarch Illia II used the concept of "celestial, heavenly Georgia": an otherworldly Georgia, where Orthodox Christian Georgians could acquire an eternal place in paradise. A prominent Georgian nationalist, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, closely linked Georgian ethnicity with Orthodox Christianity. His speeches were imbued with religious themes. He often used phrases such as "Christ-like sacrifice of Georgian nation", "inevitable revival", "protection of the Holy Virgin", "long live an independent, free, Christian, invincible Georgia" and many other. The legend about Virgin Mary picking Georgia as a place where she would spread the word of Christ after Jesus ascended to heaven served as an inspiring narrative for Georgian exceptionalism and a sense of uniqueness. According to ethno-religious nationalism, Orthodox Christianity is "national faith" and "ancestral religion", which preserved Georgian ethnicity, language and nationhood throughout the history of struggles with Muslim empires. Orthodox Christianity is seen as being wholly bound up with Georgia's national history – historically, Georgia was surrounded by Muslim empires like Ottoman Empire, Safavid Iran, Great Seljuk Empire, Arab Caliphate and others, and only Orthodox Christianity allowed Georgia to avoid being absorbed by these external powers. Thus, Orthodox Christianity historically shaped Georgian identity. Therefore, according to this view, Orthodox Christianity and Georgian nation are inseparable concepts, and to be considered as "True Georgian", one needs to be devoted Orthodox Christian. Orthodox Christianity is seen as "nourishing faith" for the nation, and in the words of one of the priest: "As a human being is the harmony of soul and flesh, similarly faith nourishes the nation and you cannot divide them. It has to be one entity".

Independent Georgia

Georgian nationalism emerged as a powerful force in the independent Georgia. Zviad Gamsakhurdia, a nationalist dissident, became the first democratically elected President of Georgia in the post-Soviet era. Researcher Stephen F. Jones describes Gamsakhurdia's view of the nation as "romantic, premodern, and transcendent". Gamsakhurdia is quoted saying:

Nationalism has been turned into a buzzword by socialists, communists, cosmopolitans, degenerate national nihilists. Nationalism is condemned in the world by those amorphous, untraditional, denationalized conglomerates that have no history, no self-contained culture; who want to turn humanity into a homogeneous mass, driven only by beastly instincts and interest in material values.

Despite nationalist rhetoric, President Zviad Gamsakhurdia signed into law the Citizenship Act of July 1991, which granted citizenship to all residents of the republic and children of stateless people born in Georgia. In mid-1991, he conceded to the Abkhaz on the reform of the electoral law and granted the Abkhaz wide over-representation in the Supreme Soviet (the Abkhaz, who were minority in Abkhazia, were granted majority of seats). This was criticized by the Georgians in Abkhazia, who regarded this change as "apartheid".

Nationalist parties were also present in the opposition as well, namely National Democratic Party and National Independence Party. Gia Chanturia included slogan "Georgia for Georgians" in the political program of NDP, a slogan which often featured at the nationalist demonstrations along with other slogans such as "The Soviet Union is the Prison of Nations" and "Long Live a Free, Democratic Georgia".

Tensions between Zviad Gamsakhurdia and his opposition led to 1991–1992 Georgian coup d'état. Under next president, Eduard Shevardnadze, a nationalist discourse weakened on state level. However, a nationalist movement reemerged in public during the last years of Shevardnadze’s rule. It emphasized supreme authority of the Georgian Orthodox Church as a pillar of the national survival. Many prominent nationalist groups and figures emerged during this period. In 1995, Guram Sharadze founded the nationalist Ena, Mamuli, Sartsmunoeba ("Language, Homeland, Religion") movement and his own party Georgia First of All. Sharadze was elected to the Parliament of Georgia and actively supported Basil Mkalavishvili ("Father Basil"), an excommunicated Georgian Orthodox priest who led a vigilate group to defend Orthodox Christianity from recent emergence of so-called "religious sects", such as Jehovah's Witnesses. They also campaigned against the spread of pornography and other material which "corrupts public morals". Basil Mklavashvili and his group favored militant tactics against perceived threats to Georgian nation. Georgian Patriarch Illia II, who did not publicly support vigilante tactics, also expressed concerns about religious sects. In one of his sermons, he said:

The Georgian people have been Christian from the first century and must stay so. Sects and foreign religions should not influence our nation. Georgia was saved by Orthodox Christianity and [Orthodox Christianity] will save it another time. Our people should walk on this way, and the ones betraying Orthodoxy, our church, Svetitskhoveli, will be the traitors of the nation, that is why every man, who would support spreading a sects beliefs and various religions, is declared as an enemy of the Georgian nation.

Basil Mkalavishvili and his group conducted vigilante activity against "the cults which are flooding the country" and "threatening Georgian religion". Since 1999, the group often disrupted meetings of Jehovah's Witnesses and burnt their literature. They also burnt Playboy journals and other "pornographic material". According to Father Basil, he was defending the motherland and the “faith of our fathers”. In 2002, MP Guram Sharadze's party – Georgia First of All – spearheaded, though unsuccessfully, a drive to try to ban the Jehovah's Witness religious denomination from the country, filling a lawsuit in the court to prohibit the organization for "anti-national" and "anti-state propaganda". In 1999, Guram Sharadze organized a campaign against opening first McDonald's restaurant in Tbilisi, saying that it would jeopardize Georgia's national cuisine. He also spearheaded campaigns to ban several Western-funded NGOs, including Liberty Institute, for their liberal-minded work and denounced businessman George Soros.

In January 1999, a heated debate developed in Georgian media over amendments which removed "ethnicity" section in newly issued passports. Many protested against the new law, including MP Guram Sharadze. According to Sharadze, for a small nation like Georgians in a difficult demographic situation, knowledge about ethnic processes is very important. The law deprived Georgians of the possibility of regulating the country’s demographic situation and would turn Georgia into "test-ground for cosmopolitanism". Sharadze accused the parliamentarians who supported the bill of "spiritual and national genocide" of Georgians. He was supported by members of the Democratic Union for Revival, Georgia's Writers Union and other cultural institutions. However, the campaign ultimately failed as the law was not revised by the parliament.

Less mainstream groups in their publications focused on struggle against Jewish and Masonic powers who were seen as seeking to undermine Georgian national identity, its faith and church through encroaching globalization. Small religious magazine Metekhi wrote about global Jewish-Masonic conspiracy that run the world, while Eldar Nadiradze's book Who are the Jehovah’s Witnesses and How Do They Do Battle Against Orthodoxy characterized Jehovah’s Witnesses as part of Masonic plot to undermine nations.

Several left-wing parties and figures also often used left-wing nationalist rhetoric in their speechs and programs. Georgian Labor Party, Socialist Party and Industrialists fiercely criticized the Shevardnadze government for implementing recommendations of International Monetary Fund and allowing cheap goods from Turkey, accusing the Georgian government of following "foreign directives" and acting like a "colonial administration". Shalva Natelashvili of Labor Party also opposed removing "ethnicity" section from passports and called on to revise the law.

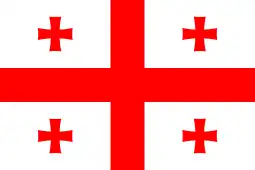

In 2003, Rose Revolution occurred in Georgia, which replaced President Shevardnadze with Mikheil Saakashvili. In his inaugural speech, Saakashvili promoted the idea that Georgia deserved its "rightful place" in the European civilization due to its Christian heritage. The new flag was adopted, which was based on medieval flag of the Kingdom of Georgia and featured five Christian crosses. Despite this, Saakashvili's nationalism differed from the ethno-religious nationalism and has been described as civic nationalism. In his speeches, Saakashvili emphasized civil identity over ethnic and religious identity. In 2004, Saakashvili conducted purges against Basil Mkalavishvili and his supporters, whom Saakashvili described as "extremist forces". Father Basil was arrested by the special forces. Also, unlike ethno-religious nationalists who emphasized the need to defend Georgian nation from the influences of the globalization, Saakashvili promoted the greatest possible engagement with the globalization, opening doors for foreign investments, relaxing visa policy for foreign citizens to attract more tourists and immigrants, and seeking integration with EU and NATO. Thus, Saakashvili’s nationalism has been described as "the strongest globalizing forces Georgia ever knew". Saakashvili's nationalism emphasized Euro-Atlantic integration as a "national idea" of Georgians and, similarily to Gamsakhurdia's nationalism, perceived Russia as a historic enemy that oppressed its cultures and people and punished Georgia for its social, political, and cultural resistance against Russian domination. However, unlike Gamsakhurdia's nationalism, Saakashvili's nationalism embodied liberal elements.

Georgian nationalist parties and organizations

Defunct

- Committee for the Independence of Georgia

- Georgian Socialist-Federalist Revolutionary Party

- National Democrats of Georgia

- Samani (Young Nationalist Fighters for the Prosperity of Georgia)

- Tetri Giorgi

- Gorgasliani

- Round Table—Free Georgia

- Union of Georgian Traditionalists

- National Independence Party of Georgia

- National Democratic Party

- People's Front

- Ilia Chavchavadze Society

- Georgian Legion

- Ivane Machabeli Society

- Ena, Mamuli, Sartsmunoeba ("Language, Homeland, Faith")

Current

- Georgian Power

- Georgian March (2017–present)

- Georgian National Unity (fascist)

Prominent nationalist figures

Sources

- Jones, Stephen (2013). Georgia: A Political History Since Independence. I.B. Tauris. p. 21. ISBN 9781784530853. Retrieved 12 January 2019 – via Google Books.

- Sabanadze 2010, Online.

- Sabanadze 2010, Online.

- Sabanadze 2010, Online.

- Jones 2009, p. 254.

- Sabanadze 2010, Online.

- Sabanadze 2010, Online.

- Suny 1994, p. 207.

- Jones 2009, pp. 254–255.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (27 January 2006). "A tolerant nationalism". St. Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- Jones 1997, p. 508.

- Cornell 2000, p. 135.

- Ketevan Gotsiridze, "An attempt to form Civic nationalism in the Democratic Republic of Georgia of 1918-1921", Tbilisi, 2017, p. 41

- Sabanadze 2010, Online.

- Jones 2009, pp. 255–256.

References

- Chikovani, Nino (July 2012). "The Georgian historical narrative: From pre-Soviet to post-Soviet nationalism". Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict. 5 (2): 107–115. doi:10.1080/17467586.2012.742953. S2CID 143918888.

- Cornell, Svante (2000). Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus. Routledge. ISBN 0700711627.

- Jones, Stephen F. (1997). "Georgia: the Trauma of Statehood". In Bremmer, Ian; Taras, Ray (eds.). New States, New Politics: Building the Post-Soviet Nations. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521577993.

- Jones, Stephen (2009). "Georgia: Nationalism from under the Rubble". In Barrington, Lowell W. (ed.). After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 248–276. ISBN 978-0472025084.

- Jones, Stephen F. (2013). Georgia: a political history since independence. London; New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781845113384.

- Sabanadze, Natalie (2010). Globalization and Nationalism: The Cases of Georgia and the Basque Country. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9789633860069.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation (2nd ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253209153.