German invasion of Greece

The German invasion of Greece, also known as the Battle of Greece or Operation Marita (German: Unternehmen Marita[13]), was the attacks on Greece by Italy and Germany during World War II. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usually known as the Greco-Italian War, was followed by the German invasion in April 1941. German landings on the island of Crete (May 1941) came after Allied forces had been defeated in mainland Greece. These battles were part of the greater Balkans Campaign of the Axis powers and their associates.

| Battle of Greece | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Balkans Campaign during World War II | |||||||||

Germany's attack on Greece | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Allies: | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Germany:[1][2] 680,000 men 1,200 tanks 700 aircraft 1Italy:[3] 565,000 men 463 aircraft[4] 163 tanks Total: 1,245,000 men |

1Greece:[5] 450,000 men Britain, Australia & New Zealand:[6][7][8][9] 252,612 men 100 tanks 200–300 aircraft Total: 502,612 men | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1Italy:[9] 19,755 dead 63,142 wounded 25,067 missing 3Germany:[10] 7,599 dead 10,752 wounded 385 missing |

1Greece:[9][11] 13,408 dead 42,485 wounded 1,290 missing 270,000 captured British Commonwealth:[6] 903 dead 1,250 wounded 13,958 captured | ||||||||

|

1 Statistics about the strength and casualties of Italy and Greece refer to both the Greco-Italian War and the Battle of Greece (at least 300,000 Greek soldiers fought in Albania).[2] 2 Including Cypriots and Mandatory Palestinians. British, Australian and New Zealand troops were c. 58,000.[6] 3 Statistics about German casualties refer to the Balkans Campaign as a whole and are based on Hitler's statements to the Reichstag on 4 May 1941.[9][10][12] | |||||||||

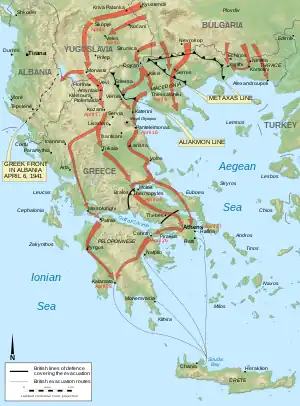

Following the Italian invasion on 28 October 1940, Greece, with British air and material support, repelled the initial Italian attack and a counter-attack in March 1941. When the German invasion, known as Operation Marita, began on 6 April, the bulk of the Greek Army was on the Greek border with Albania, then a vassal of Italy, from which the Italian troops had attacked. German troops invaded from Bulgaria, creating a second front. Greece received a small reinforcement from British, Australian and New Zealand forces in anticipation of the German attack. The Greek army found itself outnumbered in its effort to defend against both Italian and German troops. As a result, the Metaxas defensive line did not receive adequate troop reinforcements and was quickly overrun by the Germans, who then outflanked the Greek forces at the Albanian border, forcing their surrender. British, Australian and New Zealand forces were overwhelmed and forced to retreat, with the ultimate goal of evacuation. For several days, Allied troops played an important part in containing the German advance on the Thermopylae position, allowing ships to be prepared to evacuate the units defending Greece.[14] The German Army reached the capital, Athens, on 27 April and Greece's southern shore on 30 April, capturing 7,000 British, Australian and New Zealand personnel and ending the battle with a decisive victory. The conquest of Greece was completed with the capture of Crete a month later. Following its fall, Greece was occupied by the military forces of Germany, Italy and Bulgaria.[15]

Hitler later blamed the failure of his invasion of the Soviet Union on Mussolini's failed conquest of Greece.[16] Andreas Hillgruber has accused Hitler of trying to deflect blame for his country's defeat from himself to his ally, Italy.[17] It nevertheless had serious consequences for the Axis war effort in the North African theatre. Enno von Rintelen, who was the military attaché in Rome, emphasises, from the German point of view, the strategic mistake of not taking Malta.[18]

History

Greco-Italian War

At the outbreak of World War II, Ioannis Metaxas—the fascist-style dictator of Greece and former general—sought to maintain a position of neutrality. Greece was subject to increasing pressure from Italy, culminating in the Italian submarine Delfino sinking the cruiser Elli on 15 August 1940.[19] Italian leader Benito Mussolini was irritated that Nazi leader Adolf Hitler had not consulted him on his war policy and wished to establish his independence.[b] He hoped to match German military success by taking Greece, which he regarded as an easy opponent.[20][21] On 15 October 1940, Mussolini and his closest advisers finalised their decision.[c] In the early hours of 28 October, Italian Ambassador Emanuele Grazzi presented Metaxas with a three-hour ultimatum, demanding free passage for troops to occupy unspecified "strategic sites" within Greek territory.[22] Metaxas rejected the ultimatum (the refusal is commemorated as Greek national holiday Ohi Day) but even before it expired, Italian troops had invaded Greece through Albania.[d] The principal Italian thrust was directed toward Epirus. Hostilities with the Greek army began at the Battle of Elaia–Kalamas, where they failed to break the defensive line and were forced to halt.[23] Within three weeks, the Greek army launched a counter-offensive, during which it marched into Albanian territory, capturing significant cities such as Korça and Sarandë.[24] Neither a change in Italian command nor the arrival of substantial reinforcements improved the position of the Italian army.[25] On 13 February, General Papagos, the Commander-in-Chief of the Greek army, opened a new offensive, aiming to take Tepelenë and the port of Vlorë with British air support but the Greek divisions encountered stiff resistance, stalling the offensive that practically destroyed the Cretan 5th Division.[26]

After weeks of inconclusive winter warfare, the Italians launched a counter-offensive on the centre of the front on 9 March 1941, which failed, despite the Italians' superior forces. After one week and 12,000 casualties, Mussolini called off the counter-offensive and left Albania twelve days later.[27][28]

Modern analysts believe that the Italian campaign failed because Mussolini and his generals initially allocated insufficient resources to the campaign (an expeditionary force of 55,000 men), failed to reckon with the autumn weather, attacked without the advantage of surprise and without Bulgarian support.[29][30][31] Elementary precautions such as issuing winter clothing had not been taken.[32] Mussolini had not considered the warnings of the Italian Commission of War Production, that Italy would not be able to sustain a full year of continuous warfare until 1949.[33]

During the six-month fight against Italy, the Hellenic army made territorial gains by eliminating Italian salients. Greece did not have a substantial armaments industry and its equipment and ammunition supplies increasingly relied on stocks captured by British forces from defeated Italian armies in North Africa. To man the Albanian battlefront, the Greek command was forced to withdraw forces from Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace, because Greek forces could not protect Greece's entire border. The Greek command decided to support its success in Albania, regardless of the risk of a German attack from the Bulgarian border.[34]

|

|

| Italian invasion and initial Greek counter-offensive 28 October – 18 November 1940 |

Greek counter-offensive and stalemate 14 November 1940 – 23 April 1941 |

Hitler's decision to attack and British aid to Greece

I wanted, above all, to ask you to postpone the operation until a more favourable season, in any case until after the presidential election in America. In any event I wanted to ask you not to undertake this action without previously carrying out a blitzkrieg operation on Crete. For this purpose I intended to make practical suggestions regarding the employment of a parachute and an airborne division.

Letter by Adolf Hitler addressed to Mussolini on 20 November 1940[35]

Britain was obliged to assist Greece by the Declaration of 13 April 1939, which stated that in the event of a threat to Greek or Romanian independence, "His Majesty's Government would feel themselves bound at once to lend the Greek or Romanian Government... all the support in their power."[36] The first British effort was the deployment of Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons commanded by Air Commodore John D'Albiac that arrived in November 1940.[37][6] With Greek government consent, British forces were dispatched to Crete on 31 October to guard Souda Bay, enabling the Greek government to redeploy the 5th Cretan Division to the mainland.[38][39]

Hitler decided to intervene on 4 November 1940, four days after British troops arrived at Crete and Lemnos. Although Greece was neutral until the Italian invasion, the British troops that were sent as defensive aid created the possibility of a frontier to the German southern flank. Hitler's principal fear was that British aircraft based in Greece would bomb the Romanian oil fields, which was one of Germany's most important sources of oil.[40] As Hitler was already seriously considering launching an invasion of the Soviet Union the next year, this increased the importance of Romanian oil as once Germany was at war with the Soviet Union, Romania would be the Reich's only source of oil, at least until the Wehrmacht presumably captured the Soviet oil fields in the Caucasus.[40] As the British were indeed contemplating using the Greek air fields to bomb the Romanian oil fields, Hitler's fears that his entire war machine might be paralyzed for a lack of oil should the Ploești oil fields be destroyed were to a certain extent grounded in reality.[40] However, the American historian Gerhard Weinberg noted: "...the enormous difficulties of air attacks on distant oil fields were not understood by either side at this time; it was assumed on both sides that even small air raids could bring about vast fire and destruction".[40] Furthermore, the massive Italian defeats in the Balkans, the Horn of Africa and North Africa had pushed the Fascist regime in Italy to the brink of collapse by late 1940 with Mussolini becoming extremely unpopular with the Italian people. Hitler was convinced that if he did not rescue Mussolini, Fascist Italy would be knocked out of the war in 1941.[40] Weinberg wrote the continuing Italian defeats "....could easily lead to the complete collapse of the whole system Mussolini had established, and this was recognized at the time; it is not hindsight from 1943".[40] If Italy was knocked out of the war, then the British would be able to use the central Mediterranean again, and the governors of the French colonies in Africa loyal to the Vichy regime might switch their loyalties to the French National Committee headed by Charles de Gaulle.[40] As Hitler had plans to ultimately use the French colonies in Africa as bases for the war against Britain, the potential loss of Vichy control over its African empire was seen as a problem by him.[41]

Furthermore, after Italy entered the war in June 1940, the danger of Axis air and naval attacks had largely closed the central Mediterranean to British shipping except for convoys to Malta, in effect closing the Suez canal as the British were forced to supply their forces in Egypt via the long Cape route around Africa.[42] The British had made liberating Italian East Africa a priority to end the possibility of Italian naval and air attacks on British shipping in the Red Sea, which assumed greater importance because of the dangers posed to British shipping in the central Mediterranean.[43] In turn, the decision by Field Marshal Archibald Wavell to deploy significant forces to the Horn of Africa while defending Egypt lessened the number of Commonwealth forces available to go to Greece.[44] Although the performance of the Italian armed forces had been less than impressive, from the German perspective denying the British access to the central Mediterranean by stationing Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine forces in Italy made it crucial to keep Italy in the war.[45] Hitler ordered his Army General Staff to attack Northern Greece from bases in Romania and Bulgaria in support of his master plan to deprive the British of Mediterranean bases.[46][19]

On 12 November, the German Armed Forces High Command issued Directive No. 18, in which they scheduled simultaneous operations against Gibraltar and Greece for the following January. On 17 November 1940, Metaxas proposed a joint offensive in the Balkans to the British government, with Greek strongholds in southern Albania as the operational base. The British were reluctant to discuss Metaxas' proposal, because the troops necessary for implementing the Greek plan would seriously endanger operations in North Africa.[47] In December 1940, German ambitions in the Mediterranean underwent considerable revision when Spain's General Francisco Franco rejected the Gibraltar attack.[48] Consequently, Germany's offensive in southern Europe was restricted to the Greek campaign. The Armed Forces High Command issued Directive No. 20 on 13 December 1940, outlining the Greek campaign under the code designation Operation Marita. The plan was to occupy the northern coast of the Aegean Sea by March 1941 and to seize the entire Greek mainland, if necessary.[46][19][49] To attack Greece would require going through Yugoslavia and/or Bulgaria. The Regent of Yugoslavia for the boy king Peter II, Prince Paul was married to a Greek princess and refused the German request for transit rights to invade Greece.[50] King Boris III of Bulgaria had long-standing territorial disputes with Greece, and was more open to granting transit rights to the Wehrmacht in exchange for a promise to have the parts of Greece that he coveted.[50] In January 1941, Bulgaria granted the transit rights to the Wehrmacht.[50]

During a meeting of British and Greek military and political leaders in Athens on 13 January 1941, General Alexandros Papagos, Commander-in-Chief of the Hellenic Army, asked Britain for nine fully equipped divisions and corresponding air support. The British responded that all they could offer was the immediate dispatch of a token force of less than divisional strength. This offer was rejected by the Greeks, who feared that the arrival of such a contingent would precipitate a German attack without giving them meaningful assistance.[e] British help would be requested if and when German troops crossed the Danube from Romania into Bulgaria.[51][38] The Greek leader, General Metaxas, did not particularly want British forces on the mainland of Greece as he feared it would lead to a German invasion of his country and during the winter of 1940–41 secretly asked Hitler if he was willing to mediate an end to the Italo-Greek war.[52] The British prime minister, Winston Churchill, strongly supported by the chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir John Dill, and the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, had hopes of reviving the Salonika front strategy and opening a second front in the Balkans that would tie down German forces and deprive Germany of the Romanian oil.[53] The Australian prime minister, Robert Menzies, arrived in London on 20 February to discuss the deployment of Australian troops from Egypt to Greece, and reluctantly gave his approval on 25 February.[54] Like many other Australians of his generation, Menzies was haunted by the memory of the Battle of Gallipoli, and was highly suspicious of another of Churchill's plans for victory in the Mediterranean.[54] On 9 March, New Zealand's prime minister, Peter Fraser, likewise gave his approval to redeploy the New Zealand division from Egypt to Greece, despite his fears of another Gallipoli. As he put it in a telegram to Churchill, he "could not contemplate the possibility of abandoning the Greeks to their fate" which "would destroy the moral basis of our cause".[55] The weather in the winter of 1940–41 seriously delayed the build-up of German forces in Romania and it was only in February 1941 that the Wehrmacht's Twelfth Army commanded by Field Marshal Wilhelm List joined by the Luftwaffe's Fliegerkorps VIII crossed the Danube river into Bulgaria. [50] The lack of bridges on the Danube capable of carrying heavy supplies on the Romanian-Bulgarian frontier forced the Wehrmacht engineers to build the necessary bridges in wintertime, imposing major delays.[56] By 9 March 1941, the 5th and 11th Panzer Divisions were concentrated on the Bulgarian–Turkish border to deter Turkey, Greece's Balkan Pact ally from intervening.[50]

The Yugoslav coup came suddenly out of the blue. When the news was brought to me on the morning of the 27th, I thought it was a joke.

Hitler speaking to his Commanders-in-Chief [57]

Under heavy German diplomatic pressure, Prince Paul had Yugoslavia join the Tripartite Pact on 25 March 1941, but with a proviso that Yugoslavia would not grant transit rights to the Wehrmacht to attack Greece.[58] As the Metaxas Line protected the Greek–Bulgarian border, the Wehrmacht generals much preferred the idea of attacking Greece via Yugoslavia instead of Bulgaria.[59] During a hasty meeting of Hitler's staff after the unexpected 27 March Yugoslav coup d'état against the Yugoslav government, orders for the campaign in Yugoslavia were drafted, as well as changes to the plans for Greece. The coup d'état in Belgrade greatly assisted German planning as it allowed the Wehrmacht to plan an invasion of Greece via Yugoslavia.[58] The American historians Allan Millett and Williamson Murray wrote from the Greek perspective, it would have had been better if the Yugoslav coup d'état had not taken place as it would have forced the Wehrmacht to assault the Metaxas Line without the option of outflanking the Metaxas Line by going through Yugoslavia.[58] On 6 April, both Greece and Yugoslavia were to be attacked.[19][60]

British Expeditionary Force

We did not then know that he [Hitler] was already deeply set upon his gigantic invasion of Russia. If we had we should have felt more confidence in the success of our policy. We should have seen that he risked falling between two stools and might easily impair his supreme undertaking for the sake of a Balkan preliminary. This is what actually happened, but we could not know that at the time. Some may think we builded rightly; at least we builded better than we knew at the time. It was our aim to animate and combine Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey. Our duty so far as possible was to aid the Greeks.

Winston Churchill[61]

Little more than a month later, the British reconsidered. Winston Churchill aspired to reestablish a Balkan Front comprising Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey, and instructed Anthony Eden and Sir John Dill to resume negotiations with the Greek government.[61] A meeting attended by Eden and the Greek leadership, including King George II, Prime Minister Alexandros Koryzis—the successor of Metaxas, who had died on 29 January 1941—and Papagos took place in Athens on 22 February, where it was decided to send an expeditionary force of British and other Commonwealth forces.[62] German troops had been massing in Romania and on 1 March, Wehrmacht forces began to move into Bulgaria. At the same time, the Bulgarian Army mobilised and took up positions along the Greek frontier.[61]

On 2 March, Operation Lustre—the transportation of troops and equipment to Greece—began and 26 troopships arrived at the port of Piraeus.[63][64] On 3 April, during a meeting of British, Yugoslav and Greek military representatives, the Yugoslavs promised to block the Struma valley in case of a German attack across their territory.[65] During this meeting, Papagos stressed the importance of a joint Greco-Yugoslavian offensive against the Italians, as soon as the Germans launched their offensive.[f] By 24 April more than 62,000 Empire troops (British, Australians, New Zealanders, Palestine Pioneer Corps and Cypriots), had arrived in Greece, comprising the 6th Australian Division, the New Zealand 2nd Division and the British 1st Armoured Brigade.[66] The three formations later became known as 'W' Force, after their commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson.[g] Air Commodore Sir John D'Albiac commanded British air forces in Greece.[67]

Prelude

Topography

To enter Northern Greece, the German army had to cross the Rhodope Mountains, which offered few river valleys or mountain passes capable of accommodating the movement of large military units. Two invasion courses were located west of Kyustendil; another was along the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border, via the Struma river valley to the south. Greek border fortifications had been adapted for the terrain and a formidable defence system covered the few available roads. The Struma and Nestos rivers cut across the mountain range along the Greek-Bulgarian frontier and both of their valleys were protected by strong fortifications, as part of the larger Metaxas Line. This system of concrete pillboxes and field fortifications, constructed along the Bulgarian border in the late 1930s, was built on principles similar to those of the Maginot Line. Its strength resided mainly in the inaccessibility of the intermediate terrain leading up to the defence positions.[68][69]

Strategy

Greece's mountainous terrain favored a defensive strategy, while the high ranges of the Rhodope, Epirus, Pindus and Olympus mountains offered many defensive opportunities. Air power was required to protect defending ground forces from entrapment in the many defiles. Although an invading force from Albania could be stopped by a relatively small number of troops positioned in the high Pindus mountains, the northeastern part of the country was difficult to defend against an attack from the north.[71]

Following a March conference in Athens, the British believed that they would combine with Greek forces to occupy the Haliacmon Line—a short front facing north-eastwards along the Vermio Mountains and the lower Haliacmon river. Papagos awaited clarification from the Yugoslav government and later proposed to hold the Metaxas Line—by then a symbol of national security to the Greek populace—and not withdraw divisions from Albania.[72][73][5] He argued that to do so would be seen as a concession to the Italians. The strategically important port of Thessaloniki lay practically undefended and transportation of British troops to the city remained dangerous.[72] Papagos proposed to take advantage of the area's terrain and prepare fortifications, while also protecting Thessaloniki.[74]

General Dill described Papagos' attitude as "unaccommodating and defeatist" and argued that his plan ignored the fact that Greek troops and artillery were capable of only token resistance.[75] The British believed that the Greek rivalry with Bulgaria—the Metaxas Line was designed specifically for war with Bulgaria—as well as their traditionally good terms with the Yugoslavs—left their north-western border largely undefended.[68] Despite their awareness that the line was likely to collapse in the event of a German thrust from the Struma and Axios rivers, the British eventually acceded to the Greek command. On 4 March, Dill accepted the plans for the Metaxas line and on 7 March agreement was ratified by the British Cabinet.[75][76] The overall command was to be retained by Papagos and the Greek and British commands agreed to fight a delaying action in the north-east.[71] The British did not move their troops, because General Wilson regarded them as too weak to protect such a broad front. Instead, he took a position some 65 kilometres (40 miles) west of the Axios, across the Haliacmon Line.[77][5] The two main objectives in establishing this position were to maintain contact with the Hellenic army in Albania and to deny German access to Central Greece. This had the advantage of requiring a smaller force than other options, while allowing more preparation time, but it meant abandoning nearly the whole of Northern Greece, which was unacceptable to the Greeks for political and psychological reasons. The line's left flank was susceptible to flanking from Germans operating through the Monastir Gap in Yugoslavia.[78] The rapid disintegration of the Yugoslav Army and a German thrust into the rear of the Vermion position was not expected.[71]

The German strategy was based on using so-called "blitzkrieg" methods that had proved successful during the invasions of Western Europe. Their effectiveness was confirmed during the invasion of Yugoslavia. The German command again coupled ground troops and armour with air support and rapidly drove into the territory. Once Thessaloniki was captured, Athens and the port of Piraeus became principal targets. Piraeus, was virtually destroyed by bombing on the night of the 6/7 April.[79] The loss of Piraeus and the Isthmus of Corinth would fatally compromise withdrawal and evacuation of British and Greek forces.[71]

Defence and attack forces

The Fifth Yugoslav Army took responsibility for the south-eastern border between Kriva Palanka and the Greek border. The Yugoslav troops were not fully mobilised and lacked adequate equipment and weapons. Following the entry of German forces into Bulgaria, the majority of Greek troops were evacuated from Western Thrace. By this time, Greek forces defending the Bulgarian border totalled roughly 70,000 men (sometimes labelled the "Greek Second Army" in English and German sources, although no such formation existed). The remainder of the Greek forces—14 divisions (often erroneously referred to as the "Greek First Army" by foreign sources)—was committed in Albania.[80]

On 28 March, the Greek Central Macedonia Army Section—comprising the 12th and 20th Infantry Divisions—were put under the command of General Wilson, who established his headquarters to the north-west of Larissa. The New Zealand division took position north of Mount Olympus, while the Australian division blocked the Haliacmon valley up to the Vermion range. The RAF continued to operate from airfields in Central and Southern Greece, but few planes could be diverted to the theatre. The British forces were near to fully motorised, but their equipment was more suited to desert warfare than to Greece's steep mountain roads. They were short of tanks and anti-aircraft guns and the lines of communication across the Mediterranean were vulnerable, because each convoy had to pass close to Axis-held islands in the Aegean; despite the British Royal Navy's domination of the Aegean Sea. These logistical problems were aggravated by the limited availability of shipping and Greek port capacity.[81]

The German Twelfth Army—under the command of Field Marshal Wilhelm List—was charged with the execution of Operation Marita. His army was composed of six units:

- First Panzer Group, under the command of General Ewald von Kleist.

- XL Panzer Corps, under Lieutenant General Georg Stumme.

- XVIII Mountain Corps, under Lieutenant General Franz Böhme.

- XXX Infantry Corps, under Lieutenant General Otto Hartmann.

- L Infantry Corps, under Lieutenant General Georg Lindemann.

- 16th Panzer Division, deployed behind the Turkish-Bulgarian border to support the Bulgarian forces in case of a Turkish attack.[82]

German plan of attack and assembly

The German plan of attack was influenced by their army's experiences during the Battle of France. Their strategy was to create a diversion through the campaign in Albania, thus stripping the Hellenic Army of manpower for the defence of their Yugoslavian and Bulgarian borders. By driving armoured wedges through the weakest links of the defence chain, penetrating Allied territory would not require substantial armour behind an infantry advance. Once Southern Yugoslavia was overrun by German armour, the Metaxas Line could be outflanked by highly mobile forces thrusting southward from Yugoslavia. Thus, possession of Monastir and the Axios valley leading to Thessaloniki became essential for such an outflanking maneuver.[83]

The Yugoslav coup d'état led to a sudden change in the plan of attack and confronted the Twelfth Army with a number of difficult problems. According to the 28 March Directive No. 25, the Twelfth Army was to create a mobile task force to attack via Niš toward Belgrade. With only nine days left before their final deployment, every hour became valuable and each fresh assembly of troops took time to mobilise. By the evening of 5 April, the forces intended to enter southern Yugoslavia and Greece had been assembled.[84]

German invasion

Thrust across southern Yugoslavia and the drive to Thessaloniki

At dawn on 6 April, the German armies invaded Greece, while the Luftwaffe began an intensive bombardment of Belgrade. The XL Panzer Corps began their assault at 05:30. They pushed across the Bulgarian frontier into Yugoslavia at two separate points. By the evening of 8 April, the 73rd Infantry Division captured Prilep, severing an important rail line between Belgrade and Thessaloniki and isolating Yugoslavia from its allies. On the evening of 9 April, Stumme deployed his forces north of Monastir, in preparation for attack toward Florina. This position threatened to encircle the Greeks in Albania and W Force in the area of Florina, Edessa and Katerini.[85] While weak security detachments covered his rear against a surprise attack from central Yugoslavia, elements of the 9th Panzer Division drove westward to link up with the Italians at the Albanian border.[86]

The 2nd Panzer Division (XVIII Mountain Corps) entered Yugoslavia from the east on the morning of 6 April and advanced westward through the Strumica Valley. It encountered little resistance, but was delayed by road clearance demolitions, mines and mud. Nevertheless, the division was able to reach the day's objective, the town of Strumica. On 7 April, a Yugoslav counter-attack against the division's northern flank was repelled, and the following day, the division forced its way across the mountains and overran the thinly manned defensive line of the Greek 19th Mechanised Division south of Doiran Lake.[87] Despite many delays along the mountain roads, an armoured advance guard dispatched toward Thessaloniki succeeded in entering the city by the morning of 9 April.[88] Thessaloniki was taken after a long battle with three Greek divisions under the command of General Bakopoulos, and was followed by the surrender of the Greek Eastern Macedonia Army Section, taking effect at 13:00 on 10 April.[89][90] In the three days it took the Germans to reach Thessaloniki and breach the Metaxas Line, some 60,000 Greek soldiers were taken prisoner.[11]

Greek-Yugoslav counteroffensive

In early April 1941, Greek, Yugoslav and British commanders met to set in motion a counteroffensive, that planned to completely destroy the Italian army in Albania in time to counter the German invasion and allow the bulk of the Greek army to take up new positions and protect the border with Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.[91][92] On 7 April, the Yugoslav 3rd Army in the form of five infantry divisions (13th "Hercegovacka", 15th "Zetska", 25th "Vardarska", 31st "Kosovska" and 12th "Jadranska" Divisions, with the "Jadranska" acting as the reserve), after a false start due to the planting of a bogus order,[93] launched a counteroffensive in northern Albania, advancing from Debar, Prisren and Podgorica towards Elbasan. On 8 April, the Yugoslav vanguard, the "Komski" Cavalry Regiment crossed the treacherous Accursed Mountains and captured the village of Koljegcava in the Valbonë River Valley, and the 31st "Kosovska" Division, supported by Savoia-Marchetti S.79K bombers from the 7th Bomber Regiment of the Royal Yugoslav Air Force (VVKJ), broke through the Italian positions in the Drin River Valley. The "Vardarska" Division, due to the fall of Skopje was forced to halt its operations in Albania. In the meantime, the Western Macedonia Army Section under General Tsolakoglou, comprising the 9th and 13th Greek Divisions, advanced in support of the Royal Yugoslav Army, capturing some 250 Italians on 8 April. The Greeks were tasked with advancing towards Durrës.[94] On 9 April, the Zetska Division advanced towards Shkodër and the Yugoslav cavalry regiment reached the Drin River, but the Kosovska Division had to halt its advance due to the appearance of German units near Prizren. The Yugoslav-Greek offensive was supported by S.79K bombers from the 66th and 81st Bomber Groups of the VVKJ, that attacked airfields and camps around Shkodër, as well as the port of Durrës, and Italian troop concentrations and bridges on the Drin and Buene rivers and Durrës, Tirana and Zara.[95]

Between 11 and 13 April 1941, with German and Italian troops advancing on its rear areas, the Zetska Division was forced to retreat back to the Pronisat River by the Italian 131st Armored Division "Centauro", where it remained until the end of the campaign on 16 April. The Italian armoured division along with the 18th Infantry Division "Messina" then advanced upon the Yugoslav fleet base of Kotor in Montenegro, also occupying Cettinje and Podgorica. The Yugoslavs lost 30,000 men captured in the Italian counterattacks.[96]

Metaxas Line

The Metaxas Line was defended by the Eastern Macedonia Army Section, led by Lieutenant General Konstantinos Bakopoulos) and comprising the 7th, 14th and 18th Infantry divisions. The line ran for about 170 km (110 mi) along the river Nestos to the east and then further east, following the Bulgarian border as far as Mount Beles near the Yugoslav border. The fortifications were designed to garrison over 200,000 troops but there were only about 70,000 and the infantry garrison was thinly spread.[97] Some 950 men under the command of Major Georgios Douratsos of the 14th Division defended Fort Roupel.[91]

The Germans had to break the Metaxas line, in order to capture Thessaloniki, Greece's second-largest city and a strategically important port. The attack started on 6 April with one infantry unit and two divisions of the XVIII Mountain Corps. Due to strong resistance, the first day of the attack yielded little progress in breaking the line.[98][99] A German report at the end of the first day described how the German 5th Mountain Division "was repulsed in the Rupel Pass despite strongest air support and sustained considerable casualties".[100] Two German battalions managed to get within 600 ft (180 m) of Fort Rupel on 6 April, but were practically destroyed. Of the 24 forts that made up the Metaxas Line, only two had fallen and only after they had been destroyed.[98] In the following days, the Germans pummelled the forts with artillery and dive bombers and reinforced the 125th Infantry Regiment. Finally, a 7,000 ft (2,100 m) high snow-covered mountainous passage considered inaccessible by the Greeks was crossed by the 6th Mountain Division, which reached the rail line to Thessaloniki on the evening of 7 April.[101]

The 5th Mountain Division, together with the reinforced 125th Infantry Regiment, crossed the Struma river under great hardship, attacking along both banks and clearing bunkers until they reached their objective on 7 April. Heavy casualties caused them to temporarily withdraw. The 72nd Infantry Division advanced from Nevrokop across the mountains. Its advance was delayed by a shortage of pack animals, medium artillery and mountain equipment. Only on the evening of 9 April did it reach the area north-east of Serres.[99] Most fortresses—like Fort Roupel, Echinos, Arpalouki, Paliouriones, Perithori, Karadag, Lisse and Istibey—held until the Germans occupied Thessaloniki on 9 April,[102] at which point they surrendered under General Bakopoulos' orders. Nevertheless, minor isolated fortresses continued to fight for a few days more and were not taken until heavy artillery was used against them. This gave time for some retreating troops to evacuate by sea.[103][104] Although eventually broken, the defenders of the Metaxas Line succeeded in delaying the German advance.[105]

Capitulation of the Greek army in Macedonia

The XXX Infantry Corps on the left wing reached its designated objective on the evening of 8 April, when the 164th Infantry Division captured Xanthi. The 50th Infantry Division advanced far beyond Komotini towards the Nestos river. Both divisions arrived the next day. On 9 April, the Greek forces defending the Metaxas Line capitulated unconditionally following the collapse of Greek resistance east of the Axios river. In a 9 April estimate of the situation, Field Marshal List commented that as a result of the swift advance of the mobile units, his 12th Army was now in a favourable position to access central Greece by breaking the Greek build-up behind the Axios river. On the basis of this estimate, List requested the transfer of the 5th Panzer Division from First Panzer Group to the XL Panzer Corps. He reasoned that its presence would give additional punch to the German thrust through the Monastir Gap. For the continuation of the campaign, he formed an eastern group under the command of XVIII Mountain Corps and a western group led by XL Panzer Corps.[106]

Breakthrough to Kozani

By the morning of 10 April, the XL Panzer Corps had finished its preparations for the continuation of the offensive and advanced in the direction of Kozani. The 5th Panzer Division, advancing from Skopje encountered a Greek division tasked with defending Monastir Gap, rapidly defeating the defenders.[107] First contact with Allied troops was made north of Vevi at 11:00 on 10 April. German SS troops seized Vevi on 11 April, but were stopped at the Klidi Pass just south of town. During the next day, the SS regiment reconnoitered the Allied positions and at dusk launched a frontal attack against the pass. Following heavy fighting, the Germans broke through the defence.[108] By the morning of 14 April, the spearheads of the 9th Panzer Division reached Kozani.[109]

Olympus and Servia passes

Wilson faced the prospect of being pinned by Germans operating from Thessaloniki, while being flanked by the German XL Panzer Corps descending through the Monastir Gap. On 13 April, he withdrew all British forces to the Haliacmon river and then to the narrow pass at Thermopylae.[110] On 14 April, the 9th Panzer Division established a bridgehead across the Haliacmon river, but an attempt to advance beyond this point was stopped by intense Allied fire. This defence had three main components: the Platamon tunnel area between Olympus and the sea, the Olympus pass itself and the Servia pass to the south-east. By channelling the attack through these three defiles, the new line offered far greater defensive strength. The defences of the Olympus and Servia passes consisted of the 4th New Zealand Brigade, 5th New Zealand Brigade and the 16th Australian Brigade. For the next three days, the advance of the 9th Panzer Division was stalled in front of these resolutely held positions.[111][112]

A ruined castle dominated the ridge across which the coastal pass led to Platamon. During the night of 15 April, a German motorcycle battalion supported by a tank battalion attacked the ridge, but the Germans were repulsed by the New Zealand 21st Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Neil Macky, which suffered heavy losses in the process. Later that day, a German armoured regiment arrived and struck the coastal and inland flanks of the battalion, but the New Zealanders held. After being reinforced during the night of the 15th–16th, the Germans assembled a tank battalion, an infantry battalion and a motorcycle battalion. The infantry attacked the New Zealanders' left company at dawn, while the tanks attacked along the coast several hours later.[113] The New Zealanders soon found themselves enveloped on both sides, after the failure of the Western Macedonia Army to defend the Albanian town of Korça that fell unopposed to the Italian 9th Army on 15 April, forcing the British to abandon the Mount Olympus position and resulting in the capture of 20,000 Greek troops.[114]

The New Zealand battalion withdrew, crossing the Pineios river; by dusk, they had reached the western exit of the Pineios Gorge, suffering only light casualties.[113] Macky was informed that it was "essential to deny the gorge to the enemy until 19 April even if it meant extinction".[115] He sank a crossing barge at the western end of the gorge once all his men were across and set up defences. The 21st Battalion was reinforced by the Australian 2/2nd Battalion and later by the 2/3rd. This force became known as "Allen force" after Brigadier "Tubby" Allen. The 2/5th and 2/11th battalions moved to the Elatia area south-west of the gorge and were ordered to hold the western exit possibly for three or four days.[116]

On 16 April, Wilson met Papagos at Lamia and informed him of his decision to withdraw to Thermopylae. Lieutenant-General Thomas Blamey divided responsibility between generals Mackay and Freyberg during the leapfrogging move to Thermopylae. Mackay's force was assigned the flanks of the New Zealand Division as far south as an east–west line through Larissa and to oversee the withdrawal through Domokos to Thermopylae of the Savige and Zarkos Forces and finally of Lee Force; Brigadier Harold Charrington's 1st Armoured Brigade was to cover the withdrawal of Savige Force to Larissa and thereafter the withdrawal of the 6th Division under whose command it would come; overseeing the withdrawal of Allen Force which was to move along the same route as the New Zealand Division. The British, Australian and New Zealand forces remained under attack throughout the withdrawal.[117]

On the morning of 18 April, the Battle of Tempe Gorge, the struggle for the Pineios Gorge, was over when German armoured infantry crossed the river on floats and 6th Mountain Division troops worked their way around the New Zealand battalion, which was subsequently dispersed. On 19 April, the first XVIII Mountain Corps troops entered Larissa and took possession of the airfield, where the British had left their supply dump intact. The seizure of ten truckloads of rations and fuel enabled the spearhead units to continue without ceasing. The port of Volos, at which the British had re-embarked numerous units during the prior few days, fell on 21 April; there, the Germans captured large quantities of valuable diesel and crude oil.[118]

Withdrawal and surrender of the Greek Epirus Army

It is impossible for me to understand why the Greek Western Army does not make sure of its retreat into Greece. The Chief of the Imperial Staff states that these points have been put vainly time after time.

Winston Churchill[119]

As the invading Germans advanced deep into Greek territory, the Epirus Army Section of the Greek army operating in Albania was reluctant to retreat. By the middle of March, especially after the Tepelene offensive, the Greek army had suffered, according to British estimates, 5,000 casualties, and it was fast approaching the end of its logistical tether.[120]

General Wilson described this unwillingness to retreat as "the fetishistic doctrine that not a yard of ground should be yielded to the Italians."[121] Churchill also criticized the Greek Army commanders for ignoring British advice to abandon Albania and avoid encirclement. Lieutenant-General Georg Stumme's XL Corps captured the Florina-Vevi Pass on 11 April, but unseasonal snowy weather then halted his advance. On 12 April, he resumed the advance, but spent the whole day fighting Brigadier Charrington's 1st Armoured Brigade at Proastion.[122] It was not until 13 April that the first Greek elements began to withdraw toward the Pindus mountains. The Allies' retreat to Thermopylae uncovered a route across the Pindus mountains by which the Germans might flank the Hellenic army in a rearguard action. An elite SS formation—the Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler brigade—was assigned the mission of cutting off the Greek Epirus Army's line of retreat from Albania by driving westward to the Metsovon pass and from there to Ioannina.[123] On 13 April, attack aircraft from 21, 23 and 33 Squadrons from the Hellenic Air Force (RHAF), attacked Italian positions in Albania.[124] That same day, heavy fighting took place at Kleisoura pass, where the Greek 20th Division covering the Greek withdrawal, fought in a determined manner, delaying Stumme's advance practically a whole day.[122] The withdrawal extended across the entire Albanian front, with the Italians in hesitant pursuit.[111] On 15 April, Regia Aeronautica fighters attacked the (RHAF) base at Paramythia, 50 kilometres (30 mi) south of Greece's border with Albania, destroying or putting out of action 17 VVKJ aircraft that had recently arrived from Yugoslavia.[125]

General Papagos rushed Greek units to the Metsovon pass where the Germans were expected to attack. On 14 April a pitched battle between several Greek units and the LSSAH brigade—which had by then reached Grevena—erupted.[111] The Greek 13th and Cavalry Divisions lacked the equipment necessary to fight against an armoured unit, and on 15 April were finally encircled and overwhelmed.[122] On 18 April, General Wilson in a meeting with Papagos, informed him that the British and Commonwealth forces at Thermopylai would carry on fighting till the first week of May, providing that Greek forces from Albania could redeploy and cover the left flank.[126] On 21 April, the Germans advanced further and captured Ioannina, the final supply route of the Greek Epirus Army.[127] Allied newspapers dubbed the Hellenic army's fate a modern-day Greek tragedy. Historian and former war-correspondent Christopher Buckley – when describing the fate of the Hellenic army – stated that "one experience[d] a genuine Aristotelian catharsis, an awe-inspiring sense of the futility of all human effort and all human courage."[128]

On 20 April, the commander of Greek forces in Albania—Lieutenant General Georgios Tsolakoglou—accepted the hopelessness of the situation and offered to surrender his army, which then consisted of fourteen divisions.[111] Papagos condemned Tsolakoglou's decision to capitulate, although lieutenant general Ioannis Pitsikas and major general Georgios Bakos had warned him a week earlier that morale in the Epirus Army was wearing thin, and combat stress and exhaustion had resulted in officers taking the decision to put deserters before firing squads.[129] Historian John Keegan writes that Tsolakoglou "was so determined... to deny the Italians the satisfaction of a victory they had not earned that... he opened [a] quite unauthorised parley with the commander of the German SS division opposite him, Sepp Dietrich, to arrange a surrender to the Germans alone."[130] On strict orders from Hitler, negotiations were kept secret from the Italians and the surrender was accepted.[111] Outraged by this decision, Mussolini ordered counter-attacks against the Greek forces, which were repulsed, but at some cost to the defenders.[131] The Luftwaffe intervened in the renewed fighting, and Ioannina was practically destroyed by Stukas.[132] It took a personal representation from Mussolini to Hitler to organize Italian participation in the armistice that was concluded on 23 April.[130] Greek soldiers were not rounded up as prisoners of war and were allowed instead to go home after the demobilisation of their units, while their officers were permitted to retain their side arms.[133][134]

Thermopylae position

As early as 16 April, the German command realised that the British were evacuating troops on ships at Volos and Piraeus. The campaign then took on the character of a pursuit. For the Germans, it was now primarily a question of maintaining contact with the retreating British forces and foiling their evacuation plans. German infantry divisions were withdrawn due to their limited mobility. The 2nd and 5th Panzer Divisions, the 1st SS Motorised Infantry Regiment and both mountain divisions launched a pursuit of the Allied forces.[135]

To allow an evacuation of the main body of British forces, Wilson ordered the rearguard to make a last stand at the historic Thermopylae pass, the gateway to Athens. General Freyberg's 2nd New Zealand Division was given the task of defending the coastal pass, while Mackay's 6th Australian Division was to hold the village of Brallos. After the battle Mackay was quoted as saying "I did not dream of evacuation; I thought that we'd hang on for about a fortnight and be beaten by weight of numbers."[136] When the order to retreat was received on the morning of 23 April, it was decided that the two positions were to be held by one brigade each. These brigades, the 19th Australian and 6th New Zealand were to hold the passes as long as possible, allowing the other units to withdraw. The Germans attacked at 11:30 on 24 April, met fierce resistance, lost 15 tanks and sustained considerable casualties.[137][138] The Allies held out the entire day; with the delaying action accomplished, they retreated in the direction of the evacuation beaches and set up another rearguard at Thebes.[137] The Panzer units launching a pursuit along the road leading across the pass made slow progress because of the steep gradient and difficult hairpin bends.[139]

German drive on Athens

After abandoning the Thermopylae area, the British rearguard withdrew to an improvised switch position south of Thebes, where they erected a last obstacle in front of Athens. The motorcycle battalion of the 2nd Panzer Division, which had crossed to the island of Euboea to seize the port of Chalcis and had subsequently returned to the mainland, was given the mission of outflanking the British rearguard. The motorcycle troops encountered only slight resistance and on the morning of 27 April 1941, the first Germans entered Athens, followed by armoured cars, tanks and infantry. They captured intact large quantities of petroleum, oil and lubricants ("POL"), several thousand tons of ammunition, ten trucks loaded with sugar and ten truckloads of other rations in addition to various other equipment, weapons and medical supplies.[141] The people of Athens had been expecting the Germans for several days and confined themselves to their homes with their windows shut. The previous night, Athens Radio had made the following announcement:

The quarrel over the troops' victorious entry into Athens was a chapter to itself: Hitler wanted to do without a special parade, to avoid injuring Greek national pride. Mussolini, alas, insisted on a glorious entry into the city for his Italian troops. The Führer yielded to the Italian demand and together the German and Italian troops marched into Athens. This miserable spectacle, laid on by our gallant ally, must have produced some hollow laughter from the Greeks.

You are listening to the voice of Greece. Greeks, stand firm, proud and dignified. You must prove yourselves worthy of your history. The valor and victory of our army has already been recognised. The righteousness of our cause will also be recognised. We did our duty honestly. Friends! Have Greece in your hearts, live inspired with the fire of her latest triumph and the glory of our army. Greece will live again and will be great, because she fought honestly for a just cause and for freedom. Brothers! Have courage and patience. Be stout hearted. We will overcome these hardships. Greeks! With Greece in your minds you must be proud and dignified. We have been an honest nation and brave soldiers.[143]

The Germans drove straight to the Acropolis and raised the Nazi flag. According to the most popular account of the events, the Evzone soldier on guard duty, Konstantinos Koukidis, took down the Greek flag, refusing to hand it to the invaders, wrapped himself in it, and jumped off the Acropolis. Whether the story was true or not, many Greeks believed it and viewed the soldier as a martyr.[137]

Evacuation of Empire forces

General Archibald Wavell, the commander of British Army forces in the Middle East, when in Greece from 11 to 13 April had warned Wilson that he must expect no reinforcements and had authorised Major General Freddie de Guingand to discuss evacuation plans with certain responsible officers. Nevertheless, the British could not at this stage adopt or even mention this course of action; the suggestion had to come from the Greek Government. The following day, Papagos made the first move when he suggested to Wilson that W Force be withdrawn. Wilson informed Middle East Headquarters and on 17 April, Rear-Admiral Baillie-Grohman was sent to Greece to prepare for the evacuation.[145] That day Wilson hastened to Athens where he attended a conference with the King, Papagos, d'Albiac and Rear admiral Charles Edward Turle. In the evening, after telling the King that he felt he had failed him in the task entrusted to him, Prime Minister Koryzis committed suicide.[146] On 21 April, the final decision to evacuate Empire forces to Crete and Egypt was taken and Wavell – in confirmation of verbal instructions – sent his written orders to Wilson.[147][148]

We cannot remain in Greece against wish of Greek Commander-in-Chief and thus expose country to devastation. Wilson or Palairet should obtain endorsement by Greek Government of Papagos' request. Consequent upon this assent, evacuation should proceed, without however prejudicing any withdrawal to Thermopylae position in co-operation with the Greek Army. You will naturally try to save as much material as possible.

Churchill's response to the Greek proposal on 17 April 1941[149]

Little news from Greece, but 13,000 men got away to Crete on Friday night and so there are hopes of a decent percentage of evacuation. It is a terrible anxiety... War Cabinet. Winston says "We will lose only 5,000 in Greece." We will in fact lose at least 15,000. W. is a great man, but he is more addicted to wishful thinking every day.

Robert Menzies, Excerpts from his personal diary, 27 and 28 April 1941[150]

5,200 men, mostly from the 5th New Zealand Brigade, were evacuated on the night of 24 April, from Porto Rafti of East Attica, while the 4th New Zealand Brigade remained to block the narrow road to Athens, dubbed the 24 Hour Pass by the New Zealanders.[151] On 25 April (Anzac Day), the few RAF squadrons left Greece (D'Albiac established his headquarters in Heraklion, Crete) and some 10,200 Australian troops evacuated from Nafplio and Megara.[152][153] 2,000 more men had to wait until 27 April, because Ulster Prince ran aground in shallow waters close to Nafplio. Because of this event, the Germans realised that the evacuation was also taking place from the ports of the eastern Peloponnese.[154]

On 25 April the Germans staged an airborne operation to seize the bridges over the Corinth Canal, with the double aim of cutting off the British line of retreat and securing their own way across the isthmus. The attack met with initial success, until a stray British shell destroyed the bridge.[155] The 1st SS Motorised Infantry Regiment (named LSSAH), assembled at Ioannina, thrust along the western foothills of the Pindus Mountains via Arta to Missolonghi and crossed over to the Peloponnese at Patras in an effort to gain access to the isthmus from the west. Upon their arrival at 17:30 on 27 April, the SS forces learned that the paratroops had already been relieved by Army units advancing from Athens.[141]

The Dutch troop ship Slamat was part of a convoy evacuating about 3,000 British, Australian and New Zealand troops from Nafplio in the Peloponnese. As the convoy headed south in the Argolic Gulf on the morning of 27 April, it was attacked by a Staffel of nine Junkers Ju 87s of Sturzkampfgeschwader 77, damaging Slamat and setting her on fire. The destroyer HMS Diamond rescued about 600 survivors and HMS Wryneck came to her aid, but as the two destroyers headed for Souda Bay in Crete another Ju 87 attack sank them both. The total number of deaths from the three sinkings was almost 1,000. Only 27 crew from Wryneck, 20 crew from Diamond, 11 crew and eight evacuated soldiers from Slamat survived.[156][157]

The erection of a temporary bridge across the Corinth canal permitted 5th Panzer Division units to pursue the Allied forces across the Peloponnese. Driving via Argos to Kalamata, from where most Allied units had already begun to evacuate, they reached the south coast on 29 April, where they were joined by SS troops arriving from Pyrgos.[141] The fighting on the Peloponnese consisted of small-scale engagements with isolated groups of British troops who had been unable to reach the evacuation point. The attack came days too late to cut off the bulk of the British troops in Central Greece, but isolated the Australian 16th and 17th Brigades.[152]

By 30 April the evacuation of about 50,000 soldiers was completed,[a] but was heavily contested by the German Luftwaffe, which sank at least 26 troop-laden ships. The Germans captured around 8,000 Empire (including 2,000 Cypriot and Palestinian) and Yugoslav troops in Kalamata who had not been evacuated, while liberating many Italian prisoners from POW camps.[158][159][160] The Greek Navy and Merchant Marine played an important part in the evacuation of the Allied forces to Crete and suffered heavy losses as a result.[161] Churchill wrote:

At least eighty percent of the British forces were evacuated from eight small southern ports. This was made possible with the help of the Royal and Greek Navies. Twenty-six ships, twenty-one of which were Greek, were destroyed by air bombardment [...] The small but efficient Greek Navy now passed under British control ... Thereafter, the Greek Navy represented with distinction in many of our operations in the Mediterranean[162]

Aftermath

Triple occupation

On 13 April 1941, Hitler issued Directive No. 27, including his occupation policy for Greece.[163] He finalized jurisdiction in the Balkans with Directive No. 31 issued on 9 June.[164] Mainland Greece was divided between Germany, Italy and Bulgaria, with Italy occupying the bulk of the country (see map opposite). German forces occupied the strategically more important areas of Athens, Thessaloniki, Central Macedonia and several Aegean islands, including most of Crete. They also occupied Florina, which was claimed by both Italy and Bulgaria.[165] The Bulgarians occupied territory between the Struma river and a line of demarcation running through Alexandroupoli and Svilengrad west of the Evros River.[166] Italian troops started occupying the Ionian and Aegean islands on 28 April. On 2 June, they occupied the Peloponnese; on 8 June, Thessaly; and on 12 June, most of Attica.[164] The occupation of Greece – during which civilians suffered terrible hardships, many dying from privation and hunger – proved to be a difficult and costly task. Several resistance groups launched guerrilla attacks against the occupying forces and set up espionage networks.[167]

Battle of Crete

On 25 April 1941, King George II and his government left the Greek mainland for Crete, which was attacked by Nazi forces on 20 May 1941.[168] The Germans employed parachute forces in a massive airborne invasion and attacked the three main airfields of the island in Maleme, Rethymno and Heraklion. After seven days of fighting and tough resistance, Allied commanders decided that the cause was hopeless and ordered a withdrawal from Sfakia. During the night of 24 May, George II and his government were evacuated from Crete to Egypt.[62] By 1 June 1941, the evacuation was complete and the island was under German occupation. In light of the heavy casualties suffered by the elite 7th Fliegerdivision, Hitler forbade further large-scale airborne operations. General Kurt Student would dub Crete "the graveyard of the German paratroopers" and a "disastrous victory."[169]

Assessments

The Greek campaign ended with a complete German and Italian victory. The British did not have the military resources to carry out large simultaneous operations in both North Africa and the Balkans. Even if they had been able to block the Axis advance, they would have been unable to exploit the situation by a counter-thrust across the Balkans. The British came very near to holding Crete and perhaps other islands that would have provided air support for naval operations throughout the eastern Mediterranean.

In enumerating the reasons for the complete Axis victory in Greece, the following factors were of greatest significance:

- German superiority in ground forces and equipment;[170][171]

- The bulk of the Greek army was occupied fighting the Italians on the Albanian front.

- German air supremacy combined with the inability of the Greeks to provide the RAF with adequate airfields;[170]

- Inadequacy of British expeditionary forces, since the force available was small;[171]

- Poor condition of the Hellenic Army and its shortages of modern equipment;[170]

- Inadequate port, road and railway facilities;[171]

- Absence of a unified command and lack of cooperation between the British, Greek and Yugoslav forces;[170]

- Turkey's strict neutrality;[170] and

- The early collapse of Yugoslav resistance.[170]

Criticism of British actions

After the Allies' defeat, the decision to send British forces into Greece faced fierce criticism in Britain. Field Marshal Alan Brooke, (who became Chief of the Imperial General Staff in December 1941), considered intervention in Greece to be "a definite strategic blunder", as it denied Wavell the necessary reserves to complete the conquest of Italian Libya, or to withstand Rommel's Afrika Korps March offensive. It prolonged the North African campaign, which might have been concluded during 1941.[172]

In 1947, de Guingand asked the British government to recognise its mistaken strategy in Greece.[173] Buckley countered that if Britain had not honoured its 1939 commitment to Greece, it would have severely damaged the ethical basis of its struggle against Nazi Germany.[174] According to Heinz Richter, Churchill tried through the campaign in Greece to influence the political atmosphere in the United States and insisted on this strategy even after the defeat.[175] According to Keegan, "the Greek campaign had been an old-fashioned gentlemen's war, with honor given and accepted by brave adversaries on each side" and the vastly outnumbered Greek and Allied forces, "had, rightly, the sensation of having fought the good fight".[130] It has also been suggested the British strategy was to create a barrier in Greece to protect Turkey, the only (neutral) country standing between the Axis bloc in the Balkans and the oil-rich Middle East.[176][177] Martin van Creveld believes that the British government did everything in their power to scuttle all attempts at a separate peace between the Greeks and the Italians, in order to ensure the Greeks would keep fighting and thus draw Italian divisions away from North Africa.[178]

Freyberg and Blamey also had serious doubts about the feasibility of the operation but failed to express their reservations and apprehensions.[179] The campaign caused a furore in Australia, when it became known that when General Blamey received his first warning of the move to Greece on 18 February 1941, he was worried but had not informed the Australian Government. He had been told by Wavell that Prime Minister Menzies had approved the plan.[180] The proposal had been accepted by a meeting of the War Cabinet in London at which Menzies was present but the Australian Prime Minister had been told by Churchill that both Freyberg and Blamey approved of the expedition.[181] On 5 March, in a letter to Menzies, Blamey said that "the plan is, of course, what I feared: piecemeal dispatch to Europe" and the next day he called the operation "most hazardous". Thinking that he was agreeable, the Australian Government had already committed the Australian Imperial Force to the Greek Campaign.[182]

Impact on Operation Barbarossa

In 1942, members of the British Parliament characterised the campaign in Greece as a "political and sentimental decision". Eden rejected the criticism and argued that the UK's decision was unanimous and asserted that the Battle of Greece delayed Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union.[183] This is an argument that historians used to assert that Greek resistance was a turning point in World War II.[184] According to film-maker and friend of Adolf Hitler Leni Riefenstahl, Hitler said that "if the Italians hadn't attacked Greece and needed our help, the war would have taken a different course. We could have anticipated the Russian cold by weeks and conquered Leningrad and Moscow. There would have been no Stalingrad".[185] Despite his reservations, Field Marshall Brooke seems also to have conceded that the Balkan Campaign delayed the offensive against the Soviet Union.[172]

Bradley and Buell conclude that "although no single segment of the Balkan campaign forced the Germans to delay Barbarossa, obviously the entire campaign did prompt them to wait."[186] On the other hand, Richter calls Eden's arguments a "falsification of history".[187] Basil Liddell Hart and de Guingand point out that the delay of the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union was not among Britain's strategic goals and as a result the possibility of such a delay could not have affected its decisions about Operation Marita. In 1952, the Historical Branch of the UK Cabinet Office concluded that the Balkan Campaign had no influence on the launching of Operation Barbarossa.[188] According to Robert Kirchubel, "the main causes for deferring Barbarossa's start from 15 May to 22 June were incomplete logistical arrangements and an unusually wet winter that kept rivers at full flood until late spring."[189] This does not answer whether in the absence of these problems the campaign could have begun according to the original plan. Keegan writes:

In the aftermath, historians would measure its significance in terms of the delay Marita had or had not imposed on the unleashing of Barbarossa, an exercise ultimately to be judged profitless, since it was the Russian weather, not the contingencies of subsidiary campaigns, which determined Barbarossa's launch date.[130]

Antony Beevor wrote in 2012 about the current thinking of historians with regard to delays caused by German attacks in the Balkans that "most accept that it made little difference" to the eventual outcome of Barbarossa.[190] US Army analyst Richard Hooker Jr., calculates that the 22 June start date of Barbarossa was sufficient for the Germans to advance to Moscow by mid-August, and he says that the victories in the Balkans raised the morale of the German soldier.[191] Historian David Glantz wrote that the German invasion of the Balkans "helped conceal Barbarossa" from the Soviet leadership, and contributed to the German success in achieving strategic surprise and that while the Balkans operations contributed to delays in launching Barbarossa, these acted to discredit Soviet intelligence reports which accurately predicted the initially planned invasion date.[192] Jack P. Greene agrees that "other factors were more important" as regards the delaying of Barbarossa, but he also argues that the Panzer divisions, which had been in service during Operation Marita, "had to undergo refit".[11]

Notes

^ a: Sources do not agree on the exact number of the soldiers the British Empire managed to evacuate. According to British sources, 50,732 soldiers were evacuated.[193][194] But of these, according to G.A. Titterton, 600 men were lost in the troopship (the former Dutch liner) Slamat.[195][194] Adding 500–1,000 stragglers who reached Crete, Titterton estimates that "the numbers that left Greece and reached Crete or Egypt, including British and Greek troops, must have been around 51,000." Gavin Long (part of Australia's official history of World War II) gives a figure around 46,500, while, according to W. G. McClymont (part of New Zealand's official history of World War II), 50,172 soldiers were evacuated.[196][8] McClymont points out that "the differences are understandable if it is remembered that the embarkations took place at night and in great haste and that among those evacuated there were Greeks and refugees."[8]

^ b: On two preceding occasions Hitler had agreed that the Mediterranean and Adriatic were exclusively Italian spheres of interest. Since Yugoslavia and Greece were situated within these spheres, Mussolini felt entitled to adopt whatever policy he saw fit.[197]

^ c: According to the United States Army Center of Military History, "the almost immediate setbacks of the Italians only served to heighten Hitler's displeasure. What enraged the Führer most was that his repeated statements of the need for peace in the Balkans had been ignored by Mussolini."[197]

Nevertheless, Hitler had given Mussolini the green light to attack Greece six months earlier, acknowledging Mussolini's right to do as he saw fit in his acknowledged sphere of influence.[198]

^ d: According to Buckley, Mussolini preferred that the Greeks would not accept the ultimatum but that they would offer some kind of resistance. Buckley writes, "documents later discovered showed that every detail of the attack had been prepared... His prestige needed some indisputable victories to balance the sweep of Napoleonic triumphs of Nazi Germany."[22]

^ e: According to the United States Army Center of Military History, the Greeks informed the Yugoslavs of this decision and they in turn made it known to the German Government.[199] Papagos writes:

- This, incidentally, disposes of the German assertion that they were forced to attack us only in order to expel the British from Greece, for they knew that, if they had not marched into Bulgaria, no British troops would have landed in Greece. Their assertion was merely an excuse on their part to enable them to plead extenuating circumstances in justification of their aggression against a small nation, already entangled in a war against a Great Power. But, irrespective of the presence or absence of British troops in the Balkans, German intervention would have taken place firstly because the Germans had to secure the right flank of the German Army which was to operate against Russia according to the plans already prepared in autumn 1940 and secondly because the possession of the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula commanding the eastern end of the Mediterranean was of great strategic importance for Germany's plan of attacking Great Britain and the line of Imperial communications with the East.[200]

- This, incidentally, disposes of the German assertion that they were forced to attack us only in order to expel the British from Greece, for they knew that, if they had not marched into Bulgaria, no British troops would have landed in Greece. Their assertion was merely an excuse on their part to enable them to plead extenuating circumstances in justification of their aggression against a small nation, already entangled in a war against a Great Power. But, irrespective of the presence or absence of British troops in the Balkans, German intervention would have taken place firstly because the Germans had to secure the right flank of the German Army which was to operate against Russia according to the plans already prepared in autumn 1940 and secondly because the possession of the southern part of the Balkan Peninsula commanding the eastern end of the Mediterranean was of great strategic importance for Germany's plan of attacking Great Britain and the line of Imperial communications with the East.[200]

^ f: During the night of 6 April 1941, while the German invasion had already begun, the Yugoslavs informed the Greeks that they would implement the plan: they would attack the Italian troops in the morning of the next day at 6:00 a.m. At 3:00 a.m. of 7 April, the 13th division of the Greek Epirus Army attacked the Italian troops, occupied two heights and captured 565 Italians (15 officers and 550 soldiers). Nevertheless, the Yugoslav offensive would not take place and on 8 April, the Greek headquarters ordered the pause of the operation.[19][201]

^ g: Alanbrooke (he was not CIGS until November 1941) noted in his diary (11 November) that "are we again going to have Salonica supporters like the last war. Why will politicians never learn the simple principle of concentration of force at the vital point, and the avoidance of dispersal of effort?"

^ h: Although earmarked for Greece, the Polish Independent Carpathian Rifle Brigade and the Australian 7th Division were kept by Wavell in Egypt because of Erwin Rommel's successful thrust into Cyrenaica.[202]

Citations

- Collier 1971, p. 180.

- Helios 1945, Greek Wars.

- Richter 1998, pp. 119, 144.

- History, Hellenic Air Force, archived from the original on 12 December 2008, retrieved 25 March 2008.

- Ziemke.

- Beevor 1994, p. 26.

- Long 1953, pp. 182–183.

- McClymont 1959, p. 486.

- Richter 1998, pp. 595–597.

- Bathe & Glodschey 1942, p. 246.

- Greene 2014, p. 563.

- Hitler, Adolf,

- Smith 1986.

- Johnston 2013, p. 18.

- Dear & Foot 1995, pp. 102–106.

- Kershaw 2007, p. 178.

- Hillgruber 1993, p. 506.

- von Rintelen 1951, pp. 90, 92–93, 98–99.

- "Greece, History of". Helios.

- Buckley 1984, p. 18.

- Goldstein 1992, p. 53.

- Buckley 1984, p. 17.

- "Southern Europe 1940", War in Europe (timeline), World War-2.net.

- Buckley 1984, p. 19.

- Buckley 1984, pp. 18–20.

- Pearson 2006, p. 122.

- Bailey 1979, p. 22.

- More U-boat Aces Hunted down, 1941 Mar 16, On War, archived from the original on 30 September 2007, retrieved 30 September 2006.

- Richter 1998, p. 119.

- van Creveld 1972, p. 41.

- Rodogno 2006, pp. 29–30.

- Neville 2003, p. 165.

- Lee 2000, p. 146.

- Blau 1986, pp. 70–71.

- Blau 1986, p. 5.

- Lawlor 1994, p. 167.

- Barrass 2013.

- Blau 1986, pp. 71–72.

- Vick 1995, p. 22.

- Weinberg 2005, p. 213.

- Schreiber, Stegemann & Vogel 2008, pp. 183–186.

- Weinberg 2005, pp. 211–214.

- Weinberg 2005, p. 211.

- Murray & Millett 2000, pp. 98–108.

- Weinberg 2005, pp. 213–214.

- Blau 1986, pp. 5–7.

- Svolopoulos 1997, pp. 285, 288.

- Keitel 1979, pp. 154–155.

- Svolopoulos 1997, p. 288.

- Murray & Millett 2000, p. 102.

- Beevor 1994, p. 38.

- Weinberg 2005, p. 219.

- Weinberg 2005, pp. 216–219.

- Stockings & Hancock 2013, p. 558.

- Stockings & Hancock 2013, p. 560.

- Weinberg 2005, pp. 215–216.

- McClymont 1959, p. 158.

- Murray & Millett 2000, p. 103.

- Murray & Millett 2000, pp. 102–103.

- McClymont 1959, pp. 158–59.

- Churchill 1991, p. 420.

- Helios 1945, George II.

- Helios 1945, Greece, History of.

- Simpson 2004, pp. 86–87.

- Blau 1986, p. 74.

- Balkan Operations – Order of Battle – W-Force – 5 April 1941, Orders of Battle.

- Thomas 1972, p. 127.

- Bailey 1979, p. 37.

- Blau 1986, p. 75.

- Lawlor 1994, pp. 191–192.

- Blau 1986, p. 77.

- McClymont 1959, pp. 106–107.

- Papagos 1949, p. 115.

- Schreiber, Stegemann & Vogel 2008, pp. 494–496.

- Lawlor 1994, p. 168.

- McClymont 1959, pp. 107–108.

- Svolopoulos 1997, p. 290.

- Buckley 1984, pp. 40–45.

- "Disaster in Piraeus Harbour". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Blau 1986, p. 79.

- Blau 1986, pp. 79–80.

- Blau 1986, p. 81.

- Blau 1986, pp. 82–83.

- Blau 1986, pp. 83–84.

- McClymont 1959, p. 160.

- Blau 1986, p. 86.

- Carr 2013, p. 211.

- Blau 1986, p. 87.

- Playfair et al. 1962, p. 86.

- Shores, Cull & Malizia 2008, p. 237.

- Carr 2013, p. 162.

- Carruthers 2012, p. 10.

- Paoletti 2007, p. 178.

- Stockings & Hancock 2013, pp. 153, 183–184.

- Shores, Cull & Malizia 2008, p. 213.

- Shores, Cull & Malizia 2008, pp. 228–229.

- Buckley 1984, pp. 30–33.

- Buckley 1984, p. 50.

- Blau 1986, p. 88.

- Beevor 1994, p. 33.

- Carr 2013, pp. 206–207.

- Sampatakakis 2008, p. 23.

- Buckley 1984, p. 61.

- Blau 1986, p. 89.

- Sharpe & Westwell 2008, p. 21.

- Blau 1986, pp. 89–91.

- Cawthorne 2003, p. 91.

- Blau 1986, p. 91.

- Detwiler, Burdick & Rohwer 1979, p. 94.

- Hondros 1983, p. 52.

- Blau 1986, p. 94.

- Long 1953, ch. 5.

- Blau 1986, p. 98.

- van Crevald 1973, p. 162.

- Long 1953, p. 96.

- Long 1953, pp. 96–97.

- Long 1953, pp. 98–99.

- Blau 1986, p. 100.

- Churchill 2013, p. 199.

- Stockings & Hancock 2013, pp. 81–82.

- Beevor 1994, p. 39.

- Carr 2013, p. 225.

- Bailey 1979, p. 32.

- Carr 2013, p. 214.

- Shores, Cull & Malizia 2008, p. 248.

- Carr 2013, pp. 225–226.

- Long 1953, p. 95.

- Buckley 1984, p. 113.

- Carr 2013, pp. 218–219, 226.

- Keegan 2005, p. 158.

- Electrie 2008, p. 193.

- Faingold 2010, p. 133.

- Blau 1986, pp. 94–96.

- Hondros 1983, p. 90.

- Blau 1986, p. 103.

- Long 1953, p. 143.

- Bailey 1979, p. 33.

- Clark 2010, pp. 188–189.

- Blau 1986, p. 104.

- Sampatakakis 2008, p. 28.

- Blau 1986, p. 111.

- Keitel 1979, p. 166.

- Fafalios & Hadjipateras 1995, pp. 248–249.

- Long 1953, pp. 104–105.

- McClymont 1959, p. 362.

- Long 1953, p. 112.

- McClymont 1959, p. 366.

- Richter 1998, pp. 566–567, 580–581.

- McClymont 1959, pp. 362–363.

- Menzies 1941.

- Macdougall 2004, p. 194.

- Macdougall 2004, p. 195.

- Richter 1998, pp. 584–585.

- Richter 1998, p. 584.

- Blau 1986, p. 108.

- Gazette 1948, pp. 3052–3053.

- van Lierde, Ed. "Slamat Commemoration". Archived from the original on 6 January 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Blau 1986, p. 112.

- Eggenberger 1985.

- Richter 1998, p. 595.

- Shrader 1999, p. 16.

- Churchill 2013, p. 419.

- Richter 1998, p. 602.

- Richter 1998, p. 615.

- Richter 1998, p. 616.

- Richter 1998, pp. 616–617.

- Carlton 1992, p. 136.

- Helios 1945, Crete, Battle of; George II.

- Beevor 1994, p. 231.

- Blau 1986, pp. 116–118.

- McClymont 1959, pp. 471–472.

- Broad 1958, p. 113.

- Richter 1998, p. 624.

- Buckley 1984, p. 138.

- Richter 1998, p. 633.

- Lawlor 1982, pp. 936, 945.

- Stahel 2012, p. 14.

- van Creveld 1974, p. 91.

- McClymont 1959, pp. 475–476.

- McClymont 1959, p. 476.

- Richter 1998, p. 338.

- McClymont 1959, pp. 115, 476.

- Richter 1998, pp. 638–639.

- Eggenberger 1985, Greece (World War II).

- Riefenstahl 1987, p. 295.