György Dózsa

György Dózsa (or György Székely;[note 1] 1470 – 20 July 1514) was a Székely man-at-arms (and by some accounts, a nobleman) from Transylvania, Kingdom of Hungary who led a peasants' revolt against the kingdom's landed nobility. He was eventually caught, tortured, and executed along with his followers, and remembered as both a martyr and a dangerous criminal. During the reign of king Vladislaus II of Hungary (1490–1516), royal power declined in favour of the magnates, who used their power to curtail the peasants' freedom.[1]

Military career

George Dózsa was born in Dálnok (today Dalnic) around 1470. During the wars against the Ottoman Empire, he was a soldier of fortune. He spent his childhood in Dálnok with his younger brother Gergely (Gregory) Dózsa, and after the death of his father, the family moved to Makfalva. The young Dózsa was always attracted to the military career, and wanted to follow in his father's footsteps, so he later joined the army.[2]

Dózsa served in several fortresses and became known as an excellent fencer and duelist during his military service. He took part as a cavalry captain in the 1513 campaign against the Ottomans led by János Szapolyai, Voivode of Transylvania. After the campaign he remained on guard at Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade). But Dózsa's desire for glory was growing, and his fellow soldiers tried in vain to dissuade him from challenging the feared Ottoman champion Ali of Epeiro to a duel. Ali was the leader (Bey) of the Ottoman Spahi cavalry from castle of Szendrő (now Smederevo Serbia), who had already caused the death of many Hungarian valiants during his duels.[3] Ali immediately accepted the challenge, the duel was held on the field between Nándorfehérvár and Szendrő on 28 February 1514. After a desperate long but fierce struggle, Dózsa slowly managed to overcome his opponent, he cut off one of Ali's arm, and finally beheaded the Ottoman champion. With this victory, Dózsa won a nation-wide reputation and fame. For this brave deed, György Dózsa was knighted by King Valdislaus.[4][5]

From peasant crusade to rebellion

In 1514, the Hungarian chancellor, Cardinal and Archbishop Tamás Bakócz, returned from the Holy See with a papal bull issued by Leo X authorising a crusade against the Ottomans.[6] The archbishop appointed Dózsa to organize and direct the movement on 24 April 1514. On 30 April, after a solemn service, the Cardinal presented Dózsa with the symbol of the new crusade: a white flag with the red cross, blessed by the Pope.

The recruitment was probably accelerated when, at about the time of Dózsa's supposed appointment, Bakócz entrusted the recruitment to the obscurantist branch of the Franciscan order. The 'stricter' branch of the Franciscan order, which had split in the 15th century, was one of the best-established in Hungary in the 1510s, with nearly seventy monasteries and 1,700 friars throughout the country. So in the last week of April, the Franciscan friars went into action, mobilising tens of thousands of men in a few weeks. In the first week of May, 15,000 men were already in arms under Pest, and in several camps throughout the country, a further 25,000 to 30,000 peasants were waiting for the start of the operations against the Turks.[7]

Within a few weeks, Dózsa had gathered an army of some 40,000 so-called hajdú, consisting for the most part of peasants, wandering students, friars, and parish priests - some of the lowest-ranking groups of medieval society. They assembled in their counties, and by the time he had provided them with some military training, they began to air the grievances of their status. No measures had been taken to supply these voluntary crusaders with food or clothing. As harvest-time approached, the landlords commanded them to return to reap the fields, and, on their refusing to do so, proceeded to maltreat their wives and families and set their armed retainers upon the local peasantry.[8]

The volunteers became increasingly angry at the failure of the nobility to provide military leadership (the original and primary function of the nobility and the justification for its higher status in the society.)[9] The rebellious, anti-landlord sentiment of these "Crusaders" became apparent during their march across the Great Hungarian Plain, and Bakócz cancelled the campaign.[10] At that time, Bakócz stopped recruiting on the news of the clashes between peasants and nobles in Mezőtúr, and later on he stopped the whole campaign. However, György Dózsa, his brother Gergely Dózsa and several Franciscan friars, headed by the priest Lőrinc, disobeyed the order to stop the recruitment. From then on, the crusaders labelled the nobles and the king himself as pro-Ottoman traitors. After that, the peasant armies regarded the defeat of the nobility and the king as a prerequisite for victory in their crusade against the Ottoman Empire.[11]

The movement was thus diverted from its original object, and the peasants and their leaders began a war of vengeance against the landlords.[8]

Social Goals

Based on the research of professor Sándor Márki, Dózsa and his co-elected senior fellows wanted to change the church and the political system fundamentally. They aimed to have a single elected bishop for the entire country and to make all priests equal in rank. They also wanted to abolish the nobility and distribute the lands of the nobility and the Catholic Church equally among the peasants. They decided that there should be only two orders: the city burgeroise (merchants and craftsmen) and the peasants, and they also wanted to abolish the kingdom as a form of government. Dózsa himself only wanted to be the warlord and representative of the people: subordinating himself in everything to the decisions of the people.[12][13]

The formerly peasant origin Franciscan friars became the ideologues of the uprising.[14] With their help, Dózsa effectively threatened to excommunicate the religiously minded peasant-soldiers in his army if they betrayed their "holy crusader movement" and their "just" social goals.[15]

Dózsa's most notable elected co-leaders

- Gregory Dózsa (Gergely Dózsa), younger brother of György Dózsa,

- Laurence Mészáros (Lőrinc Mészáros), a Franciscan friar and parish priest of Cegléd, who in his proclamation, the Pope, II. In the name of King Vladislaus and the legate, he promised the forgiveness of all sins and otherworldly punishment to those who go to the crusade, help it and take care of its sick, but he threatened church curses to those who do not do this.[16]

- "Priest Barabbas" (Barabás),

- Ambrose Ványa (Ambrus Ványa) from turkeve, a Franciscan theologist who graduated from the university, he edited Dozsa's fiery proclamations to the people,[17][18]

- Thomas Kecskés (Tamás Kecskés) from Aszaló,[19]

- Francis Bagos (Ferenc Bagos),

- Anthony Nagy (Antal Nagy), the leader of the Kalocsa crusaders, nobleman from Sárköz,[20]

- Benedict Pogány (Benedek Pogány),

- Ambrose Száleresi (Ambrus Száleresi), a well-to-do citizen of Pest.[21][22]

Growing rebellion

I, George Dózsa, the mighty champion valiant, head and captain of the blessed people of the Crusaders, only King of Hungary - but not subject of the Lords - individually and collectively send you our greetings! To all the cities, market towns, and villages of Hungary, especially in the counties of Pest and Outer Szolnok. Know ye that the treacherous lying nobility have risen up violently against us and against all the crusading armies preparing for holy war, to persecute and exterminate us. Therefore, under the penalty of banishment and eternal damnation, not to mention the death penalty and the loss of all your goods, we strictly enjoin and order you, that immediately after receiving this letter, without delay or excuse, you hasten here to the city of Cegléd, so that you, the blessed simple people, strengthened in the covenant sanctified by you, nobles must be limited, restrained, and destroyed. If not, you will not escape the punishment of the nobles intended for you. What’s more, we ordinary commoners suspend and hang nobles on their own gates, hang on skewers, destroy their property, tear down their houses, and kill their wives and children in the midst of the greatest possible torture.

— Dózsa's speech at Cegléd

The rebellion became more dangerous when the towns joined on the side of the peasants. In Buda and elsewhere, the cavalry sent against them were unhorsed as they passed through the gates.[8]

The army was not exclusively composed of peasants of Hungarian nationality. A part of the army, about 40%, was made up of Slovaks and Rusyns from Upper Hungary, Romanians from Transylvania, Serbs from the South, and there may have been Germans, but the latter were very few in number. After the news spread about Dózsa's first victories, peasant riots took place in most places in the country, in which peasants of other nationalities, such as Slovaks, Germans, Croats, Slovenes or Serbs, also took part.

The rebellion spread quickly, principally in the central or purely Magyar provinces, where hundreds of manor houses and castles were burnt and thousands of the lower untitled gentry noblemen were killed by impalement, crucifixion, and other methods. Dózsa's camp at Cegléd was the centre of the jacquerie, as all raids in the surrounding area started out from there.[8]

In reaction, the papal bull was revoked, and King Vladislaus issued a proclamation commanding the peasantry to return to their homes under pain of death. By this time, the uprising had attained the dimensions of a revolution; all the vassals of the kingdom were called out against it, and soldiers of fortune were hired in haste from the Republic of Venice, Bohemia, and the Holy Roman Empire. Meanwhile, Dózsa had captured the city and fortress of Csanád (today's Cenad), and signaled his victory by impaling the bishop and the castellan.[8]

Subsequently, at Arad, Lord Treasurer István Telegdy was seized and tortured to death. In general, however, the rebels only executed particularly vicious or greedy noblemen; those who freely submitted were released on parole. Dózsa not only never broke his given word, but frequently assisted the escape of fugitives. He was unable to consistently control his followers, however, and many of them hunted down rivals.[8]

Downfall and execution

In the course of the summer, Dózsa seized the fortresses of Arad, Lippa (today Lipova), and Világos (now Şiria), and provided himself with cannons and trained gunners. One of his bands advanced to within 25 kilometres of the capital. But his ill-armed ploughmen were outmatched by the heavy cavalry of the nobles. Dózsa himself had apparently become demoralized by success: after Csanád, he issued proclamations which can be described as nihilistic.[8]

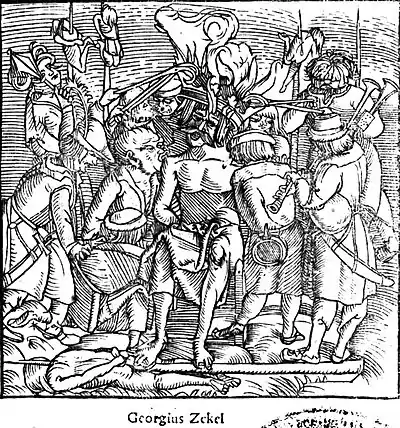

As his suppression had become a political necessity, Dózsa was routed at Temesvár (today Timișoara, Romania) by an army of 20,000[23] led by John Zápolya and István Báthory. He was captured after the battle, and condemned to sit on a smouldering, heated iron throne, and forced to wear a heated iron crown and sceptre (mocking his ambition to be king). While he was suffering, a procession of nine fellow rebels who had been starved beforehand were led to this throne.[8] In the lead was Dózsa's younger brother, Gergely, who was cut in three despite Dózsa asking for Gergely to be spared. Next, executioners removed some pliers from a fire and forced them into Dózsa's skin. After tearing his flesh, the remaining rebels were ordered to bite spots where the hot pliers had been inserted and to swallow the flesh. The three or four who refused were simply cut up, prompting the others to comply. In the end, Dózsa died from the ordeal, while the rebels who obeyed were released and left alone.[24]

The revolt was repressed but some 70,000 peasants were tortured.[25] György's execution, and the brutal suppression of the peasants, greatly aided the 1526 Ottoman invasion as the Hungarians were no longer a politically united people. Another consequence was the creation of new laws, an effort in the Hungarian Diet led by István Werbőczy. The resulting Tripartitum elaborated the old rights of peasants, but also greatly enhanced the status of lesser nobility (gentry), erecting an iron curtain between Hungarians until 1848 when serfdom was abolished.[26]

Legacy

The often biased historiography of the nobility later often claimed that the memory of György Dózsa served as a role model for other great peasant uprisings on the territory of the Hungarian crown, such as the revolt of Jovan of Czerni, which took place barely twelve years after the Dózsa War, and the peasant uprising in Croatia led by Ambroz Gubec in 1572–1573.

Today, on the site of the martyrdom of the hot throne, there is the Virgin Mary Monument, built by architect László Székely and sculptor György Kiss. According to the legend, during György Dózsa's torture, some friars saw in his ear the image of Mary. The first statue was raised in 1865, with the actual monument raised in 1906. Hungarian opera composer Ferenc Erkel wrote an opera, Dózsa György, about him.

His revolutionary image and Transylvanian background were drawn upon during the Communist regime of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. The Hungarian component of his movement was downplayed, but its strong anti-feudal character was emphasized.[27]

In Budapest, a square, a busy six-lane avenue, and a metro station bear his name, and it is one of the most popular street names in Hungarian villages. A number of streets in several cities of Romania were named Gheorghe Doja. Also, a number of streets in several cities of Serbia were named "Ulica Doža Đerđa". Two Postage stamps were issued in his honor by Hungary on 12 June 1919[28] and on 15 March 1947,[29] the latter in the "social revolutionists" series.

Notes

- appears as "Georgius Zekel" in old texts

References

- Britannica Dózsa Rebellion

- Oláh-Gál Róbert (7 August 2014). "Gondolatok Dózsa György származásáról". Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- Gergely Hidasi (2017). Saber Fencing: sport and martial art. A Szablya Iskolája Egyesület. p. 157. ISBN 9786150010120.

- Domokos Varga (1982). Hungary in Greatness and Decline: The 14th and 15th Centuries History Series Issue 13 of Publication (State University College at Buffalo. Program in East European and Slavic Studies) Volume 13 of State University of New York College at Buffalo's Program. Hungarian Cultural Foundation. p. 138. ISBN 9780914648116.

- Albert-Laszlo Barabasi (2010). Bursts: The Hidden Patterns Behind Everything We Do, from Your E-mail to Bloody Crusades. Penguin. p. 150. ISBN 9781101187166.

- Molnar p. 82

- eisz Ágoston (27 April 2014). "Nemesek nélküli államot akartak Dózsáék". origo.hu. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Bain 1911.

- Norman Housley: Religious Warfare in Europe 1400-1536 (page: 70) Oxford University Press, 2002

- http://www.history.com/topics/hungary/page4%5B%5D

- Márki Sándor: DÓSA GYÖRGY, 1470-1514

- "Márki Sándor Dósa György 1470–1514". Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Keisz Ágoston (27 April 2014). "Nemesek nélküli államot akartak Dózsáék". origo.hu. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- "Dózsa-féle parasztháború, 1514. május–július: a magyar történelem legnagyobb parasztfelkelése". lexikon.katolikus.hu. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Péter Katalin (2001). "The road from the priest's temple to the church of the congregation". Egyháztörténeti Szemle. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Fraknói Vilmos (1889). "Erdődi Bakócz Tamás élete V. fejezet Végső évei". mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Györffy Lajos (1975). "Ki volt Ványai Ambrus?, Jászkunság 1975. mátcius-június" (PDF). Jászkunság. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- "Ványai Ambrus (Túrkevey Ambrus)". new.turkeve.hu. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "Nagy Iván: Magyarország családai – Kecskés család". Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- Papp Attila (8 May 2014). "Főurakat és püspököket húztak karóba". duol.hu. Archived from the original on 28 September 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "Magyar életrajzi lexikon Száleresi Ambrus". Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- "Bánlaky József A magyar nemzet hadtörténelme – Az 1514. évi pórlázadás". Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- Molnar, p. 82

- Barbasi pp. 263–266

- "A brief history of Hungary". Archived from the original on 12 April 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- Molnar p. 83

- (in Romanian) Emanuel Copilaş, "Confiscarea lui Dumnezeu şi mecanismul inevitabilităţii istorice" Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Sfera Politicii 139, September 2009

- colnect.com/en/stamps/stamp/190132-György_Dózsa-Social_Revolutionists-Hungary

- colnect.com/en/stamps/stamp/179860-György_Dózsa_1474-1514-Hungarian_Freedom_Fighters-Hungary

Sources

- Molnar, Miklos (2001). A Concise History of Hungary. Cambridge Concise Histories (Fifth printing 2008 ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66736-4.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). "Dozsa, György". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 462.

- Barabási, Albert-László (2010). Bursts (First ed.). New York, United States: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-525-95160-5.