Pope Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (Latin: Benedictus XV; Italian: Benedetto XV), born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa[lower-alpha 2] (Italian: [ˈdʒaːkomo ˈpaːolo dʒoˈvanni batˈtista della ˈkjɛːza]; 21 November 1854 – 22 January 1922), was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His pontificate was largely overshadowed by World War I and its political, social, and humanitarian consequences in Europe.

Benedict XV | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |||||||||||||||||||

.jpg.webp) Portrait by Nicola Perscheid, 1915 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Church | Catholic Church | ||||||||||||||||||

| Papacy began | 3 September 1914 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Papacy ended | 22 January 1922 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Pius X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Pius XI | ||||||||||||||||||

| Orders | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ordination | 21 December 1878 by Raffaele Monaco La Valletta[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Consecration | 22 December 1907 by Pope Pius X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Created cardinal | 25 May 1914 by Pope Pius X | ||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa 21 November 1854 Pegli, Genoa, Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 22 January 1922 (aged 67) Apostolic Palace, Rome, Kingdom of Italy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Previous post(s) |

| ||||||||||||||||||

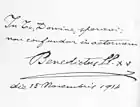

| Motto | In Te Domine Speravi, Non Confundar In Aeternum (Latin for 'In thee, o Lord, have I trusted: let me not be confounded for evermore')[lower-alpha 1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||

| Coat of arms |  | ||||||||||||||||||

Ordination history | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Between 1846 and 1903, the Catholic Church had experienced two of its longest pontificates in history up to that point. Together Pius IX and Leo XIII ruled for a total of 57 years. In 1914, the College of Cardinals chose della Chiesa at the relatively young age of 59 at the outbreak of World War I, which he labeled "the suicide of civilized Europe". The war and its consequences were the main focus of Benedict XV. He immediately declared the neutrality of the Holy See and attempted from that perspective to mediate peace in 1916 and 1917. Both sides rejected his initiatives. German Protestants rejected any "Papal Peace" as insulting. The French politician Georges Clemenceau regarded the Vatican initiative as being anti-French.[3] Having failed with diplomatic initiatives, Benedict XV focused on humanitarian efforts to lessen the impacts of the war, such as attending prisoners of war, the exchange of wounded soldiers and food deliveries to needy populations in Europe. After the war, he repaired the difficult relations with France, which re-established relations with the Vatican in 1921. During his pontificate, relations with Italy improved as well, as Benedict XV now permitted Catholic politicians led by Don Luigi Sturzo to participate in national Italian politics.

In 1917, Benedict XV promulgated the Code of Canon Law, which was released on 27 May, the creation of which he had prepared with Eugenio Pacelli (the future Pope Pius XII) and Pietro Gasparri during the pontificate of Pope Pius X. The new Code of Canon Law is considered to have stimulated religious life and activities throughout the Church.[4] He named Gasparri to be his Cardinal Secretary of State and personally consecrated Nuncio Pacelli on 13 May 1917 as Archbishop. World War I caused great damage to Catholic missions throughout the world. Benedict XV revitalized these activities, asking in Maximum illud for Catholics throughout the world to participate. For that, he has been referred to as the "Pope of Missions". His last concern was the emerging persecution of the Catholic Church in Soviet Russia and the famine there after the revolution. Benedict XV was devoted to the Blessed Virgin Mary and authorized the Feast of Mary, Mediatrix of all Graces.[5]

After seven years in office, Pope Benedict XV died on 22 January 1922 after battling pneumonia since the start of that month. He was buried in the grottos of Saint Peter's Basilica. With his diplomatic skills and his openness towards modern society, "he gained respect for himself and the papacy."[4]

Early life

Giacomo della Chiesa was born prematurely at Pegli, a suburb of Genoa, Italy, the third son and sixth child of Marchese Giuseppe della Chiesa (1821–1892) and his wife Marchesa Giovanna Migliorati (1827–1904).[6] Genealogy findings report that his father's side produced Pope Callixtus II and also claimed descent from Berengar II of Italy and that his maternal family produced Pope Innocent VII.[7] He is also a descendant of Blessed Antonio della Chiesa. His brother, Giovanni Antonio Della Chiesa, married the niece of Cardinal Angelo Jacobini.[8] Due to his premature birth, Giacomo was left with a limp and completed much of his early education at home.[9]

His wish to become a priest was rejected early on by his father, who insisted on a legal career for his son. At age 21 he acquired a doctorate in Law on 2 August 1875. He had attended the University of Genoa, which after the unification of Italy was largely dominated by anti-Catholic and anti-clerical politics. With his doctorate in Law and at legal age, he again asked his father for permission to study for the priesthood, which was now reluctantly granted. He insisted, however, that his son conduct his theological studies in Rome, not in Genoa, so that he would not end up as a village priest or provincial monsignore.[10]

Della Chiesa entered the Collegio Capranica and was there in Rome when, in 1878, Pope Pius IX died and was followed by Pope Leo XIII. The new pope received the students of the Capranica in private audience only a few days after his coronation. Shortly thereafter, della Chiesa was ordained a priest by Cardinal Raffaele Monaco La Valletta on 21 December 1878 at the Lateran basilica.[1]

From 1878 until 1883 he studied at the Pontificia Accademia dei Nobili Ecclesiastici in Rome. It was there, on every Thursday, that students were required to defend a research paper, to which cardinals and high members of the Roman Curia were invited. Mariano Rampolla, then Secretary for Oriental Affairs of the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, took note of him and furthered his entry in the diplomatic service of the Vatican in 1882, where he was employed by Rampolla as a secretary and in January 1883 accompanied nuncio Rampolla to Madrid.[1] When Rampolla subsequently was appointed Cardinal Secretary of State, della Chiesa followed him. During these years, della Chiesa helped negotiate the resolution of a dispute between Germany and Spain over the Caroline Islands as well as organising relief during a cholera epidemic.

His ambitious mother, Marchesa della Chiesa, is said to have been discontented with the career of her son, cornering Rampolla with the words, that, in her opinion, Giacomo was not properly recognised in the Vatican. Rampolla allegedly replied, "Signora, your son will take only a few steps, but they will be gigantic ones."[11]

Just after Leo XIII's death in 1903, Rampolla tried to make della Chiesa the secretary of the conclave, but the Sacred College elected Rafael Merry del Val, a conservative young prelate, the first sign that Rampolla would not be the next Pope. When Cardinal Rampolla had to leave his post with the election of his opponent Pope Pius X, and was succeeded by Merry del Val, della Chiesa was retained in his post.

Bologna

Archbishop

Della Chiesa's association with Rampolla, the architect of Pope Leo XIII's (1878–1903) foreign policy, made his position in the Secretariat of State under the new pontificate somewhat uncomfortable. Italian papers announced that on 15 April 1907 the papal nuncio Aristide Rinaldini in Madrid would be replaced by della Chiesa, who had worked there before. Pius X, chuckling over the journalist's knowledge, commented, "Unfortunately, the paper forgot to mention whom I nominated as the next Archbishop of Bologna."[12] The Vatican had supposedly "gone so far as to make out the papers naming him the papal nuncio, but [della Chiesa] refused to accept them".[13] On 18 December 1907, in the presence of his family, the diplomatic corps, numerous bishops and cardinals, and his friend Rampolla, he received the episcopal consecration from Pope Pius X himself. The Pope donated his own episcopal ring and crosier to the new bishop and spent much time with the della Chiesa family on the following day.[14] On 23 February 1908, della Chiesa took possession of his new diocese, which included 700,000 persons, 750 priests, as well as 19 male and 78 female religious institutes. In the episcopal seminary, some 25 teachers educated 120 students preparing for the priesthood.[15]

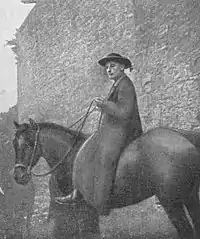

As bishop, he visited all parishes, making a special effort to see the smaller ones in the mountains which could only be accessed on horse-back. He always saw preaching as the main obligation of a bishop. He usually gave two or more sermons a day during his visitations. His emphasis was on cleanliness inside all churches and chapels and on saving money wherever possible, for he said, "Let us save to give to the poor."[16] A meeting of all priests in a synod had to be postponed at the wish of the Vatican considering ongoing changes in Canon Law. Numerous churches were built or restored. He personally originated a major reform of the educational orientation of the seminary, adding more science courses and classic education to the curriculum.[17] He organized pilgrimages to Marian shrines in Loreto and Lourdes at the 50th anniversary of the apparition.[18] The unexpected death of his friend, supporter and mentor Rampolla on 16 December 1913[19] was a major blow to della Chiesa, who was one of the beneficiaries of his will.[18]

Cardinal

It was a custom that the Archbishop of Bologna would be made a cardinal in one of the coming consistories. In Bologna this was surely expected of della Chiesa as well, since, in previous years, either cardinals were named as archbishops, or archbishops as cardinals soon thereafter.[20] Pius X did not follow this tradition and left della Chiesa waiting for almost seven years. When a delegation from Bologna visited him to ask for della Chiesa's promotion to the College of Cardinals, he jokingly replied by making fun of his own family name, Sarto (meaning "tailor"), for he said, "Sorry, but a Sarto has not been found yet to make the cardinal's robe."[20] Some suspected that Pius X or persons close to him did not want to have two Rampollas in the College of Cardinals.

Cardinal Rampolla died on 16 December 1913. On 25 May 1914, della Chiesa was created a cardinal, becoming Cardinal-Priest of the titulus Santi Quattro Coronati, which before him was occupied by Pietro Respighi. When the new cardinal tried to return to Bologna after the consistory in Rome, an unrelated socialist, anti-monarchic and anti-Catholic uprising began to take place in Central Italy. This was accompanied by a general strike, the looting and destruction of churches, telephone connections and railway buildings, and a proclamation of a secular republic. In Bologna itself, citizens and the Catholic Church opposed such developments successfully. The Socialists overwhelmingly won the following regional elections with great majorities.[21]

As World War I approached, the question was hotly discussed in Italy as to which side to be on. Officially, Italy was still in an alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. However, in the Tirol, an integral part of Austria which was mostly German-speaking, the southern part, the province of Trento, was exclusively Italian-speaking. The clergy of Bologna was not totally free from nationalistic fervor either. Therefore, in his capacity as Archbishop, on the outbreak of World War I, della Chiesa made a speech on the Church's position and duties, emphasizing the need for neutrality, promoting peace and the easing of suffering.[22]

Pontificate

| Papal styles of Pope Benedict XV | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | None |

Election to the Papacy

Following the death of Pius X, the resulting conclave opened at the end of August 1914. The war would clearly be the dominant issue of the new pontificate, so the cardinals' priority was to choose a man with great diplomatic experience. Thus on 3 September 1914, della Chiesa, despite having been a cardinal only three months, was elected pope, taking the name of Benedict XV. He chose the name in honour of Pope Benedict XIV, who was also archbishop from Bologna.[23] Upon being elected pope, he was also formally the Grand Master of the Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, prefect of the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office and prefect of the Sacred Consistorial Congregation. There was, however, a Cardinal-Secretary to run these bodies on a day-to-day basis.

Due to the enduring Roman Question, after the announcement of his election to the papacy by the Cardinal Protodeacon, Benedict XV, following in the footsteps of his two most recent predecessors, did not appear on the balcony of St. Peter's basilica overlooking St. Peter's Square to grant the urbi et orbi blessing. Benedict XV was crowned in the Sistine Chapel on 6 September 1914, and, also as a form of protest due to the Roman Question, there was no ceremony for the formal possession of the Archbasilica of Saint John Lateran.

In the 1914 conclave, the cardinals were divided into two factions: the "reactionaries" and the "conservatives". The decade-long campaign waged against Modernism cast a cloud over the conclave, and also ensured on the part of the deceased pontiff that there were fewer moderate and progressive cardinals in the Sacred College. However, the cardinals feared that one of the sides in World War I might potentially influence the conclave to elect a pope that would prove amenable to their side and their positions. While the cardinals expressed relief in the abolition of the veto in 1904, there was still a palpable fear that there would be subtle attempts to exert control over the cardinals, hence, deep suspicion in many cardinals of their European colleagues. During the conclave, Cardinal Domenico Serafini and his faction had enough votes to ensure that Della Chiesa was not elected, particularly since the eighth ballot had Della Chiesa with a majority, though below the two-thirds needed for election.[24]

While Serafini was considered "papabile" due to his position at the Holy Office, and his alignment with the policies of Pius X, other cardinals such as Andrea Carlo Ferrari and Désiré-Joseph Mercier believed that the new pope needed to focus not on Modernism and doctrinal debates, but rather, a softer focus after the somewhat harsh reign of Pius X. To that end, those cardinals turned towards electing the liberal Archbishop of Pisa Pietro Maffi. Della Chiesa, on the other hand, was wedged between Maffi and Serafini as representing the best and worst of both factions, hence his contention in the balloting. While Della Chiesa seemed to secure support from some conservative cardinals, Maffi lagged considerably and hence Serafini was positioned as Della Chiesa's main rival. Since Maffi had lagged in the balloting, his supporters decided to counter Serafini and threw their support for Della Chiesa, securing his election by only one vote in what was a protracted conclave.[24][25]

Upon his election, Benedict XV was unable to locate a suitable cassock to wear since the three that were available to him did not appropriately fit his frail form. From a diary that recorded the events of the conclave, "the papal habit that was chosen was the small one, but lacking in some part, and being a little long, it was adapted with clothespin pins, and raised and covered with a gold tassel sash".[25]

Peace efforts

Benedict XV's pontificate was dominated by World War I, which he termed, along with its turbulent aftermath, "the suicide of Europe."[26] Benedict's first encyclical extended a heartfelt plea for an end to hostilities. His early call for a general Christmas truce in 1914 was ignored, although informal truces were organized. Late in the war, in May–October 1917, the apparitions of Our Lady of Fatima occurred in Fatima, Portugal, apparitions that would be declared "worthy of belief" in 1930 during the papacy of his successor, Pius XI.

The war and its consequences were Benedict's main focus during the early years of his pontificate. He declared the neutrality of the Holy See and attempted from that perspective to mediate peace in 1916 and 1917. Both sides rejected his initiatives.

The national antagonisms between the warring parties were accentuated by religious differences before the war, with France, Italy and Belgium being largely Catholic. Vatican relations with Great Britain were good, while neither Prussia nor Imperial Germany had any official relations with the Vatican. In Protestant circles of Germany, the notion was popular that the Catholic Pope was neutral on paper only, strongly favoring the allies instead.[27] Benedict was said to have prompted Austria-Hungary to go to war in order to weaken the German war machine. Also, allegedly, the Papal Nuncio in Paris explained in a meeting of the Institut Catholique, "to fight against France is to fight against God",[27] and the Pope was said to have exclaimed that he was sorry not to be a Frenchman.[27] The Belgian Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier, known as a brave patriot during German occupation but also famous for his anti-German propaganda, was said to have been favored by Benedict XV for his enmity to the German cause. After the war, Benedict also allegedly praised the Treaty of Versailles, which humiliated the Germans.[27]

These allegations were rejected by the Vatican's Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Gasparri, who wrote on 4 March 1916 that the Holy See is completely impartial and does not favor the allied side. This was even more important, so Gasparri noted, after the diplomatic representatives of Germany and Austria-Hungary to the Vatican were expelled from Rome by Italian authorities.[28] However, considering all this, German Protestants rejected any "Papal Peace", calling it insulting. French politician Georges Clemenceau, a fierce anti-clerical, claimed to regard the Vatican initiative as anti-French. Benedict made many unsuccessful attempts to negotiate peace, but these pleas for a negotiated peace made him unpopular, even in Catholic countries like Italy, among many supporters of the war who were determined to accept nothing less than total victory.[29]

On 1 August 1917, Benedict issued a seven-point peace plan stating that:

- "the moral force of right… be substituted for the material force of arms,"

- there must be "simultaneous and reciprocal diminution of armaments,"

- a mechanism for "international arbitration must be established,"

- "true liberty and common rights over the sea" should exist,

- there should be a "renunciation of war indemnities,"

- occupied territories should be evacuated, and

- there should be "an examination… of rival claims."

Great Britain reacted favorably though popular opinion was mixed.[30] United States President Woodrow Wilson rejected the plan. Bulgaria and Austria-Hungary were also favorable, but Germany replied ambiguously.[31][32] Benedict also called for outlawing conscription,[33] a call he repeated in 1921.[34]

Some of the proposals eventually were included in Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points call for peace in January 1918.[29][35]

In Europe, each side saw him as biased in favor of the other and was unwilling to accept the terms he proposed. Still, although unsuccessful, his diplomatic efforts during the war are credited with an increase of papal prestige and served as a model in the 20th century for the peace efforts of Pius XII before and during World War II, the policies of Paul VI during the Vietnam War, and the position of John Paul II before and during the Iraq War.[29]

In addition to his efforts in the field of international diplomacy Pope Benedict also tried to bring about peace through Christian faith, as he published a special prayer in 1915 to be spoken by Catholics throughout the world.[36] There is a statue in Saint Peter's Basilica of the Pontiff absorbed in prayer, kneeling on a tomb which commemorates a fallen soldier of the war, which he described as a "useless massacre".

Humanitarian efforts

Almost from the beginning of the war, November 1914, Benedict negotiated with the warring parties about an exchange of wounded and other prisoners of war who were unable to continue fighting. Tens of thousands of such prisoners were exchanged through his intervention.[28] On 15 January 1915, he proposed an exchange of civilians from the occupied zones, which resulted in 20,000 persons being sent to unoccupied Southern France in one month.[28] In 1916, Benedict managed to hammer out an agreement between both sides by which 29,000 prisoners with lung disease from the gas attacks could be sent into Switzerland.[37] In May 1918, he also negotiated an agreement whereby prisoners on both sides with at least 18 months of captivity and four children at home would also be sent to neutral Switzerland.[28]

He succeeded in 1915 in reaching an agreement by which the warring parties promised not to let prisoners of war (POWs) work on Sundays and holidays. Several individuals on both sides were spared the death penalty after his intervention. Hostages were exchanged and corpses repatriated.[28] The Pope founded the Opera dei Prigionieri to assist in distributing information on prisoners. By the end of the war, some 600,000 items of correspondence were processed by the Vatican. Almost a third of it concerned missing persons. Some 40,000 people had asked for help in the repatriation of sick POWs and 50,000 letters were sent from families to their loved ones who were POWs.[38]

Both during and after the war, Benedict was primarily concerned about the fate of the children, on whose behalf he issued an encyclical. In 1916 he appealed to the people and clergy of the United States to help him feed the starving children in German-occupied Belgium. His aid to children was not limited to Belgium but extended to children in Lithuania, Poland, Lebanon, Montenegro, Syria and Russia.[39] Benedict was particularly appalled at the new military invention of aerial warfare and protested several times against it to no avail.[40]

In May and June 1915, the Ottoman Empire waged a genocide against the Armenian Christian minorities in Anatolia. The Vatican attempted to get Germany and Austria-Hungary involved in protesting to its Turkish ally. The Pope himself sent a personal letter to the Sultan, who was also Caliph of Islam. It had no success "as over a million Armenians died, either killed outright by the Turks or from maltreatment or starvation".[40]

After the war

At the time, the anti-Vatican resentment, combined with Italian diplomatic moves to isolate the Vatican in light of the unresolved Roman Question,[41] contributed to the exclusion of the Vatican from the Paris Peace conference of 1919 (although it was also part of a historical pattern of political and diplomatic marginalization of the papacy after the loss of the Papal States). Despite this, he wrote an encyclical pleading for international reconciliation, Pacem, Dei Munus Pulcherrimum.[42]

After the war, Benedict focused the Vatican's activities on overcoming famine and misery in Europe and establishing contacts and relations with the many new states which were created because of the demise of Imperial Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany. Large food shipments, and information about and contacts with POWs, were to be the first steps for a better understanding of the papacy in Europe.[3]

Regarding the Versailles Peace Conference, the Vatican believed that the economic conditions imposed on Germany were too harsh and threatened the European economic stability as a whole. Cardinal Gasparri believed that the peace conditions and the humiliation of the Germans would likely result in another war as soon as Germany would be militarily in a position to start one.[43] The Vatican also rejected the dissolution of Austria-Hungary, seeing in this step an inevitable and eventual strengthening of Germany.[44] The Vatican also had great reservations about the creation of small successor states which, in the view of Gasparri, were not viable economically and therefore condemned to economic misery.[45] Benedict rejected the League of Nations as a secular organization that was not built on Christian values.[46] On the other hand, he also condemned European nationalism that was rampant in the 1920s and asked for "European Unification" in his 1920 encyclical Pacem Dei Munus Pulcherrimum, "peace, a beautiful gift of God".[46] Similarly, Benedict XV extolled the virtues of peace, denouncing the fragility of a peace that is not wholly oriented towards reconciliation. Prophetically, the Pope wrote that "if almost everywhere the war somehow ended and some peace pacts were signed, the germs of ancient grudges still remain. No peace has value if hatred and enmities are not put down together by means of a reconciliation based on mutual charity".[25]

The pope was also disturbed by the communist revolution in Russia. He reacted with horror to the strongly anti-religious policies adopted by Vladimir Lenin's government along with the bloodshed and widespread famine which occurred during the subsequent Russian Civil War. He undertook the greatest efforts trying to help the victims of the Russian famine with millions in relief.[46] Following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, concerns were raised in the Vatican about the safety and future of the Catholics in the Holy Land.

Diplomatic agenda

In the post-war period, Pope Benedict XV was involved in developing the Church administration to deal with the new international system that had emerged. The papacy was faced with the emergence of numerous new states such as Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, Finland, and others. Germany, France, Italy, and Austria were impoverished from the war. In addition, the traditional social and cultural European order was threatened by right-wing nationalism and fascism as well as left-wing socialism and communism, all of which potentially threatened the existence and freedom of the Church. To deal with these and related issues, Benedict engaged in what he knew best, a large scale diplomatic offensive to secure the rights of the faithful in all countries.

Italy

Leo XIII already had agreed to the participation of Catholics in local but not national politics. Relations with Italy improved as well under Benedict XV, who de facto reversed the stiff anti-Italian policy of his predecessors by allowing Catholics to participate in national elections as well. This led to a surgence of the Partito Popolare Italiano under Luigi Sturzo. Anti-Catholic politicians were gradually replaced by persons who were neutral or even sympathetic to the Catholic Church. The King of Italy himself gave signals of his desire for better relations, when, for example, he sent personal condolences to the Pontiff on the death of his brother.[47] The working conditions for Vatican staff greatly improved and feelers were extended on both sides to solve the Roman Question. Benedict XV strongly supported a solution and seemed to have had a fairly pragmatic view of the political and social situation in Italy at this time.

Benedict XV, along with most traditional Catholics of his time, opposed voting rights for women in principle, on the grounds that it would take them out of their "natural sphere".[48] However, he was pragmatic and recognized female suffrage could be a "social necessity in some countries...in order to counter the generally subversive views of the socialists with the supposedly conservative votes of women", believing that women would help support traditional Catholic positions if granted suffrage.[49]

France

Benedict XV also attempted to improve relations with the anti-clerical Republican government of France, and canonized the French national heroine Saint Joan of Arc. In the mission territories of the Third World, he emphasized the necessity of training native priests to quickly replace the European missionaries, and founded the Pontifical Oriental Institute and the Coptic College in the Vatican. Pius XI would entrust the "Orientale" to the Jesuits and make it a part of the Jesuit's Gregorian Consortium in Rome (along with the Gregorian University and the Biblicum).[50] In 1921, France re-established diplomatic relations with the Vatican.[51]

Soviet Union

The end of the war caused the revolutionary development, which Benedict XV had foreseen in his first encyclical. With the Russian Revolution, the Vatican was faced with a new, so far unknown, situation.

Lithuania and Estonia

The relations with Russia changed drastically for a second reason. The Baltic states and Poland gained their independence from Russia after World War I, thus enabling a relatively free Church life in those former Russia-controlled countries. Estonia was the first country to look for Vatican ties. On 11 April 1919, Cardinal Secretary of State Pietro Gasparri informed the Estonian authorities that the Vatican would agree to have diplomatic relations. A concordat was agreed upon in principle a year later in June 1920. It was signed on 30 May 1922. It guaranteed freedom for the Catholic Church, established archdioceses, liberated clergy from military service, allowed the creation of seminaries and Catholic schools, and enshrined church property rights and immunity. The Archbishop swore alliance to Estonia.[52]

Relations with Catholic Lithuania were slightly more complicated because of the Polish occupation of Vilnius, a city and archiepiscopal seat, which Lithuania claimed as its own. Polish forces had occupied Vilnius and committed acts of brutality in its Catholic seminary there. This generated several protests by Lithuania to the Holy See.[53] Relations with the Holy See were defined during the pontificate of Pope Pius XI (1922–1939).

Poland

Before all other heads of state, Pope Benedict XV in October 1918 congratulated the Polish people on their independence.[54] In a public letter to Archbishop Kakowski of Warsaw, he remembered their loyalty and the many efforts of the Holy See to assist them. He expressed his hopes that Poland would again take its place in the family of nations and continue its history as an educated Christian nation.[54] In March 1919, he nominated 10 new bishops and, soon after, Achille Ratti, who was already in Warsaw as his representative, as papal nuncio.[54] He repeatedly cautioned Polish authorities against persecuting Lithuanian and Ruthenian clergy.[55] During the Bolshevik advance against Warsaw, he asked for worldwide public prayers for Poland. Nuncio Ratti was the only foreign diplomat to stay in the Polish capital. On 11 June 1921, he wrote to the Polish episcopate, warning against political misuses of spiritual power, urging again for peaceful coexistence with neighbouring peoples, stating that "love of country has its limits in justice and obligations".[56] He sent nuncio Ratti to Silesia to act against potential political agitations of the Catholic clergy.[55]

Ratti, a scholar, intended to work for Poland and build bridges to the Soviet Union, hoping even to shed his blood for Russia.[57] Pope Benedict XV needed him as a diplomat and not as a martyr and forbade any trip into the USSR even though he was the official papal delegate to Russia.[57] However, he continued his contacts with Russia. This did not generate much sympathy for him within Poland at the time. He was asked to go. While he tried honestly to show himself as a friend of Poland, Warsaw forced his departure after his neutrality in Silesian voting was questioned[58] by Germans and Poles. Nationalistic Germans objected to a Polish nuncio supervising elections, and Poles were upset because he curtailed agitating clergy.[59] On 20 November, when German Cardinal Adolf Bertram announced a papal ban on all political activities of clergymen, calls for Ratti's expulsion climaxed in Warsaw.[59] Two years later, Achille Ratti became Pope Pius XI, shaping Vatican policies towards Poland with Pietro Gasparri and Eugenio Pacelli for the following 36 years (1922–1958).

Israel

As part of the preliminary diplomatic negotiations leading to the Balfour Declaration, Pope Benedict gave his support to a Jewish homeland in Palestine to Zionist diplomat Nahum Sokolow on 4 May 1917, describing the return of the Jews to Palestine as "providential; God has willed it."[60]

United States

Cardinal James Gibbons helped secure a meeting between the pope and President Woodrow Wilson which took place on 4 January 1919. The cardinal had sent a letter to the President imploring him to visit the pope after learning that Wilson was to go to Europe. Not long after, Wilson confirmed the visit and went to meet the pope accompanied by the Pontifical North American College rector Charles O'Hearn. Benedict XV took Wilson by the hand and led him into the study for their meeting, with the pope later presenting Wilson with a gift: a mosaic of Saint Peter. The interpreter had to be present for the meeting, since the pope was speaking in French, and Wilson only spoke English. The presidential party was presented to the pope, and after presenting his personal physician Admiral Grayson (telling the pope that he "is the man who keeps me well"), the pope said: "Apparently, he has done a splendid job", before offering words to Grayson. The pope blessed the entourage, despite Wilson's slight confusion, after the pope assured Wilson his blessing did not discriminate those of other faiths, since Wilson was a Presbyterian.[61]

However, friction remained between the two during their private audience. Benedict XV wanted to be involved in the discussions at Versailles, but Wilson disagreed with this.

Ireland

Following the declaration of the Irish Republic in 1919, Benedict XV was visited by Seán T. O'Kelly in May 1920, who explained Irish politics and presented a memorandum, hoping for support from the "Sovereign Pontiff".[62]

In 1921, a peace agreement was formalized between the British Empire and the Irish Republic that saw to the end of the Irish War of Independence. Negotiations were conducted in London, however, there was a rise in tension during the negotiations over separate telegrams sent to Benedict XV by both King George V and Éamon de Valera. The telegram sent by de Valera took issue with the language that George V used in his message to the pope and responded to simply clarify the nature between both parties and the reasons that there had been tension between the two.[63] In his letter to George V, the Pope praised the ongoing efforts for peace, saying that "We rejoice at the resumption of the Anglo-Irish negotiations" and that the negotiations would "end the age-long dissention" between both sides.[64] Benedict XV further declared himself "overjoyed with the agreement happily reached in regard to Ireland".[65]

A source of contention, despite firm denials by the Holy See in 1933, is the allegation that Benedict XV, in a private interview with Count George Noble Plunkett in mid-April 1916, imparted an Apostolic Blessing to the Irish Republic just two weeks before the Easter Rising. The fact that the Pope is purported to have done so was widely accepted by Republicans, though categorically denied later by L'Osservatore Romano in 1933. Additionally, it was alleged that Plunkett pledged the Irish Republic to fidelity to the Holy See, with the Pope formally imparting his blessing on the endeavors of the Irish Republic, prompting the Archbishop of Armagh Michael Logue to send a telegram to the Pope on 30 April 1916 asking for a clarification as to what occurred during the meeting. When L'Osservatore Romano refuted these claims in 1933, the paper said that "the news was entirely unfounded" and that the actions of Benedict XV were "in open contradiction to the well-known gentleness of the late Pontiff and to his most lively desire for peace and the prevention of any further effusion of blood". Plunkett himself affirmed the truth of the allegations, saying "The fact is that the that the Papal Blessing given the men of 1916 by Pope Benedict has only one witness remaining – myself. Those who profess to refute me have not evidence to support them".[66]

Church affairs

Theology

In internal Church affairs, Benedict XV reiterated Pius X's condemnation of Modernist scholars and the errors in modern philosophical systems in Ad beatissimi Apostolorum. He declined to readmit to communion scholars who had been excommunicated during the previous pontificate. However, he calmed what he saw as the excesses of the anti-Modernist campaign within the Church. On 25 July 1920, he wrote the motu proprio Bonum sane on Saint Joseph and against naturalism and socialism.

Canon law reform

In 1917 Benedict XV promulgated the Church's first comprehensive Code of Canon Law, the preparation of which had been commissioned by Pope Pius X, and which is thus known as the Pio-Benedictine Code. This Code, which entered into force in 1918, was the first consolidation of the Church's Canon Law into a modern Code made up of simple articles. Previously, Canon Law was dispersed in a variety of sources and partial compilations. The new codification of canon law is credited with reviving religious life and providing judicial clarity throughout the Church.[4]

In addition, continuing the concerns of Leo XIII, he furthered Eastern Catholic culture, theology and liturgy by founding an Oriental Institute for them in Rome[4] and creating the Sacred Congregation for the Oriental Church in 1917. In 1919, he founded the Pontifical Ethiopian College within the Vatican walls with St. Stephen's Church, behind St. Peter's Basilica, as the College's designated church.[67]

Catholic missions

On 30 November 1919, Benedict XV appealed to all Catholics worldwide to sacrifice for Catholic missions, stating at the same time in Maximum illud that these missions should foster local culture and not import European cultures.[4] The damages of such cultural imports[68] were particularly grave in Africa and Asia, where many missionaries were deported and incarcerated if they happened to originate from a hostile nation.

Mariology

Pope Benedict personally addressed in numerous letters the pilgrims at Marian sanctuaries. He named Mary the Patron of Bavaria, and permitted, in Mexico, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception of Guadaloupe. He authorised the Feast of Mary Mediator of all Graces.[5] He condemned the misuse of Marian statues and pictures, dressed in priestly robes, which he outlawed 4 April 1916.[69]

On 10 May 1916, Pope Benedict declared the image and Marian title of Our Lady of Charity of El Cobre as Patroness of Cuba at the written request of the soldier veterans of the Cuban War of Independence.

During World War I, Benedict placed the world under the protection of the Blessed Virgin Mary and added the invocation Mary Queen of Peace to the Litany of Loreto. He promoted Marian veneration throughout the world by elevating 20 well-known Marian shrines such as Ettal Abbey in Bavaria into minor basilicas. He also promoted Marian devotions in May.[70] The dogmatic constitution on the Church issued by the Second Vatican Council quotes the Marian theology of Benedict XV.[71]

Pope Benedict issued the motu proprio Bonum sane on 25 July 1920, encouraging devotion to Saint Joseph "since through St. Joseph we go directly to Mary, and through Mary to the source of every holiness, Jesus Christ, who consecrated the domestic virtues with his obedience to St. Joseph and Mary."[72]

He issued an encyclical on Ephraim the Syrian depicting Ephraim as a model of Marian devotion, as well as the Apostolic Letter Inter Soldalica of 22 March 1918.[73]

- "As the blessed Virgin Mary does not seem to participate in the public life of Jesus Christ, and then, suddenly appears at the stations of his cross, she is not there without divine intention. She suffers with her suffering and dying son, almost as if she would have died herself. For the salvation of mankind, she gave up her rights as the mother of her son and sacrificed him for the reconciliation of divine justice, as far as she was permitted to do. Therefore, one can say, she redeemed with Christ the human race."[73]

Writings

During his seven-year pontificate, Benedict XV wrote a total of twelve encyclicals. In addition to the encyclicals mentioned, he issued In hac tanta on St. Boniface (14 May 1919), Paterno iam diu on the Children of Central Europe (24 November 1919), Spiritus Paraclitus on St. Jerome (September 1920), Principi Apostolorum Petro on St. Ephram the Syrian (5 October 1920), Annus iam plenus also on Children in Central Europe (1 December 1920), Sacra propediem on the Third Order of St. Francis (6 January 1921), In praeclara summorum on Dante (30 April 1921), and Fausto appetente die on St. Dominic (29 June 1921).

His Apostolic Exhortations include Ubi primum (8 September 1914), Allorché fummo chiamati (28 July 1915) and Dès le début (1 August 1917). The Papal bulls of Benedict XV include Incruentum Altaris (10 August 1915), Providentissima Mater (27 May 1917), Sedis huius (14 May 1919), and Divina disponente (16 May 1920). Benedict issued nine Briefs during his pontificate: Divinum praeceptum (December 1915), Romanorum Pontificum (February 1916), Cum Catholicae Ecclesiae (April 1916), Cum Biblia Sacra (August 1916), Cum Centesimus (October 1916), Centesimo Hodie (October 1916), Quod Ioannes (April 1917), In Africam quisnam (June 1920), and Quod nobis in condendo (September 1920).

Ad beatissimi Apostolorum

Ad beatissimi Apostolorum is an encyclical of Benedict XV given at St. Peter's, Rome, on the Feast of All Saints on 1 November 1914, in the first year of his pontificate. This first encyclical coincided with the beginning of World War I, which he labeled "The Suicide of Civilized Europe." Benedict described the combatants as the greatest and wealthiest nations of the earth, stating that "they are well-provided with the most awful weapons modern military science has devised, and they strive to destroy one another with refinements of horror. There is no limit to the measure of ruin and of slaughter; day by day the earth is drenched with newly shed blood and is covered with the bodies of the wounded and of the slain."[74]

In light of the senseless slaughter, the pope pleaded for "peace on earth to men of good will" (Luke 2:14), insisting that there are other ways and means whereby violated rights can be rectified.[75]

The origin of the evil is a neglect of the precepts and practices of Christian wisdom, particularly a lack of love and compassion. Jesus Christ came down from Heaven for the very purpose of restoring among men the Kingdom of Peace, as He stated, "A new commandment I give unto you: That you love one another."[76] This message is repeated in John 15:12, in which Jesus says, "This is my commandment that you love one another."[77] Materialism, nationalism, racism, and class warfare are the characteristics of the age instead, so Benedict XV described:

- "Race hatred has reached its climax; peoples are more divided by jealousies than by frontiers; within one and the same nation, within the same city there rages the burning envy of class against class; and amongst individuals it is self-love which is the supreme law over-ruling everything."[78]

Humani generis redemptionem

The encyclical Humani generis redemptionem, from 15 June 1917, deals with blatant ineffectiveness of Christian preaching. According to Benedict XV, there are more preachers of the Word than ever before, but "in the state of public and private morals as well as the constitutions and laws of nations, there is a general disregard and forgetfulness of the supernatural, a gradual falling away from the strict standard of Christian virtue, and that men are slipping back into the shameful practices of paganism."[79] The Pope squarely put part of the blame on those ministers of the Gospel who do not handle it as they should. It is not the times but the incompetent Christian preachers who are to blame, for no one today can say for sure that the Apostles were living in better times than ours. Perhaps, the encyclical states, that the Apostles found minds more readily devoted to the Gospel, or they may have met others with less opposition to the law of God.[80]

As the encyclical tells, first are the Catholic bishops. The Council of Trent taught that preaching "is the paramount duty of Bishops."[81] The Apostles, whose successors the bishops are, looked upon the Church as something theirs, for it was they who received the grace of the Holy Spirit to begin it. Saint Paul wrote to the Corinthians, "Christ sent us not to baptize, but to preach the Gospel."[82] Council of Trent Bishops are required to select for this priestly office those only who are "fit" for the position, i.e. those who "can exercise the ministry of preaching with profit to souls." Profiting souls does not mean doing such "eloquently or with popular applause, but rather with spiritual fruit."[83] The Pope requested that all the priests who are incapable of preaching or of hearing confession be removed from the position.[84] The encyclical helps to draw out the message that priests must concentrate on the Word on God and the benefitting of souls before their own selves.

Quod iam diu

Quod iam diu was an encyclical given at Rome at St. Peter's on 1 December 1918, in the fifth year of his Pontificate. It requested that, after World War I, all Catholics of the world pray for a lasting peace and for those who are entrusted to make such during peace negotiations.

The pope noted that true peace has not yet arrived, but the Armistice has suspended the slaughter and devastation by land, sea and air.[85] It is the obligation of all Catholics to "invoke Divine assistance for all who take part in the peace conference," as the encyclical states. The Pope concludes that prayer is essential for the delegates who are to meet to define peace, as they are in need of much support.[86]

Maximum illud

Maximum illud is an apostolic letter of Benedict XV issued on 30 November 1919, dealing with the Catholic missions. After reminding bishops of their responsibility to support the missions, he advised missionaries not to regard the mission as their own but to welcome others to the task and to collaborate with those around them. He underlined the necessity of proper preparation for the work in foreign cultures and the need to acquire language skills before doing such work, especially in the Orient. He tells missionaries that: "Especially among the infidels, who are guided more by instinct than by reason, preaching by example is much more profitable than that of words". He requested a continued striving for personal sanctity and praised the selfless work of women religious in the missions.[87] "Mission", however, "is not only for missionaries, but all Catholics must participate through their apostolate of prayer, by supporting vocations, and by helping financially."[88] The letter concludes with the naming of several organizations which organize and supervise mission activities within the Catholic Church.[89][90]

Internal activities

Canonizations and beatifications

Benedict XV canonized three individuals, all in May 1920: Gabriel of Our Lady of Sorrows, Joan of Arc, and Margaret Mary Alacoque. He also beatified a total of forty-six people, including the Uganda Martyrs (1920), Oliver Plunkett (1920) and Louise de Marillac (1920).

Doctor of the Church

He named Ephrem the Syrian as a Doctor of the Church on 5 October 1920.

Consistories

The pope created 32 cardinals in five consistories, elevating men into the cardinalate such as Pietro La Fontaine (1916) and Michael von Faulhaber (1921); he reserved two in pectore but later published one name (Adolf Bertram). The pope's death in 1922 therefore invalidated the second appointment (it has been alleged that the second in pectore cardinal was to be Pavel Huyn).[91] Benedict XV also created his immediate successor Achille Ratti as a cardinal in 1921.

Benedict XV elevated 31 Europeans into the College of Cardinals with Dennis Joseph Dougherty as the single non-European cardinal appointed. In the 1916 consistory, no German or Austro-Hungarian cardinals were able to attend due to the intensity of the war. In that consistory, by naming Adolf Bertram as a cardinal "in pectore", Benedict XV hoped not to provoke any negativity in his selection from the Allies, particularly the Italians. Bertram was not formally invested in the Sacred College until December 1919, after the war had concluded.

In the 1921 consistory, Benedict XV is reported to have said, that "We gave you the red robe of a Cardinal.... very soon, however, one of you will wear the white robe".[92]

Personality and appearance

Pope Benedict XV was a slight man. He wore the smallest of three cassocks that were prepared for the election of a new pope in 1914, and became known as "Il Piccoletto" or "The Little Man". The cassock he wore upon his election had to be quickly stitched up so it could properly fit him. The new pope jokingly said to the tailors: "My dear, had you forgotten me?" He was dignified in bearing and courtly in terms of manners, but his appearance was not that of a pope. He had a sallow complexion, a mat of black hair, and prominent teeth.[93] He himself had referred to his appearance as an "ugly gargoyle upon the buildings of Rome". It was even said that his father looked upon his newborn son with incredulity and turned away in dismay at the sight of the infant della Chiesa, due to the small, bluish pallor and frail appearance of the infant.[61]

He was renowned for his generosity, answering all pleas for help from poor Roman families with large cash gifts from his private revenues. When he was short on money, those who would be admitted to an audience would often be instructed by prelates not to mention their financial woes, as Benedict would inevitably feel guilty that he could not help the needy at the time. He also depleted the Vatican's official revenues with large-scale charitable expenditure during World War I. Upon his death, the Vatican Treasury had been depleted to the equivalent in Italian lire of U.S. $19,000 ($332,200 in 2023).[94]

Benedict XV was a careful innovator by Vatican standards. He was known to carefully consider all novelties before he ordered their implementation, then insisting on them to the fullest. He rejected clinging to the past for the past's sake with the words "Let us live in the present and not in history."[95] His relation to secular Italian powers was reserved yet positive, avoiding conflict and tacitly supporting the Royal Family of Italy. Yet, like Pius IX and Leo XIII, he also protested against interventions of State authorities in internal Church affairs.[95] Pope Benedict was not considered a man of letters. He did not publish educational or devotional books. His encyclicals are pragmatic and down-to-earth, intelligent and at times far-sighted. He remained neutral during the battles of the "Great War," when almost everybody else was claiming "sides." Like that of Pius XII during World War II, his neutrality was questioned by all sides then and even to this day.[96]

Benedict XV personally had a strong devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. He gave his approval to the dioceses of Belgium for a Mass and office under the title of Mary as Mediatrix of All Graces.

Death

Benedict XV celebrated Mass with the nuns at the Domus Sanctae Marthae in early January 1922 and while he waited for his driver out in the rain he fell ill with the flu which turned into pneumonia. The pope gave evidence on 5 January that he was suffering from a cold, but it was later noted on 12 January that he was suffering from a heavy cough and was feverish. On 18 January, the pope was unable to get out of bed.[97] The pope's condition grew grave on 19 January around 11:00pm after his heart grew weak due to the spreading of pneumonia, with the Holy See notifying the Italian government that the pope's condition was grave. Oxygen was administered to the pope after respiration became increasingly difficult, and Cardinal Oreste Giorgi was summoned to the pontiff's bedside to recite prayers for the dying. His condition improved slightly at midnight on 20 January, and he insisted his medical attendants withdraw for the night when it seemed he might recover.

At 2:00 am on 21 January, he was given the Extreme Unction and the pope took some liquid refreshment following an hour's sleep. It was at some stage around this time that he met privately with Cardinal Gasparri for around 20 minutes to communicate his last wishes to the cardinal, while entrusting his last will to him. A bulletin at 4:30 am indicated that the pope's speech was occasionally incoherent while another at 9:55 am indicated that the pope's agony was profound to the point he could not recognize his attendants due to his state of delirium. Another bulletin at 10:05 am said that the pope's pulse was becoming intermittent.[98] At noon, he grew delirious and insisted on rising to resume his work, but an hour later fell into a coma. By 12:30pm, Prince Chigi-Albani visited the pope's room to prepare to take possession of the apartment in the event of the pope's death and to act as a marshal for the next conclave.

False reports from Parisian and London evening papers on 21 January announced the pope's death occurring at 5:00 am that day, warranting corrections by Italian correspondents, prior to an official dispatch at 8:00 am to inform that the pope was alive.[99] Cardinal Bourne's secretary was also forced to announce on 21 January that the pope had not died after a member of the cardinal's staff mistakenly confirmed the pope had died.[100]

The death throes began at 5:20 am on 22 January, with Cardinal Giorgi granting absolution to the dying pope. Cardinal Gasparri arrived at Benedict XV's bedside at 5:30 am since the pope had fallen into a coma yet again (at 5:18 am he said that "the catastrophe is imminent"), with Doctor Cherubini pronouncing the pontiff's death at 6:00 am.[99] After his death, flags were flown at half-staff in memory of him and as a tribute to him. His body then lay in state for the people to see before being moved for burial in the Vatican grottos.

Legacy

Benedict XV made valiant efforts to end World War I. In 2005, Pope Benedict XVI recognized the significance of his long-ago predecessor's commitment to peace by taking the same name upon his own rise to the pontificate. Benedict XV's humane approach to the world in 1914–1918 starkly contrasted with most of the monarchs and leaders of the time, with few notable exceptions. His worth is reflected in the tribute engraved at the foot of the statue that the Turks, a non-Catholic, non-Christian people, erected of him in Istanbul: "The great Pope of the world tragedy,... the benefactor of all people, irrespective of nationality or religion." This monument stands in the courtyard of the St. Esprit Cathedral.

Pope Pius XII showed high regard for Benedict XV, who had consecrated him a bishop on 13 May 1917, the very day of the first reported apparitions of Our Lady of Fatima. While Pius XII considered another Benedict, Benedict XIV, in terms of his sanctity and scholarly contributions to be worthy as Doctor of the Church,[101] he thought that Benedict XV during his short pontificate was truly a man of God, who worked for peace.[102] He helped prisoners of war and many others who needed help in dire times, and was extremely generous to Russia.[103] He praised him as a Marian Pope who promoted the devotion to Our Lady of Lourdes,[104] for his encyclicals Ad beatissimi Apostolorum, Humani generis redemptionem, Quod iam diu, and Spiritus Paraclitus, and for the codification of Canon Law,[105] in which, under della Chiesa and Pietro Gasparri, Pius XII had had, as Eugenio Pacelli, the opportunity to participate.

Pope Benedict XVI showed his own admiration for Benedict XV following his election to the papacy on 19 April 2005. The election of a new Pope is often accompanied by conjecture over his choice of papal name; it is widely believed that a Pope chooses the name of a predecessor whose teachings and legacy he wishes to continue. Cardinal Ratzinger's choice of "Benedict" was seen as a signal that Benedict XV's views on humanitarian diplomacy and his stance against relativism and modernism would be emulated during the reign of the new Pope. During his first General Audience in St. Peter's Square on 27 April 2005, Pope Benedict XVI paid tribute to Benedict XV when explaining his choice:[106]

"Filled with sentiments of awe and thanksgiving, I wish to speak of why I chose the name Benedict. Firstly, I remember Pope Benedict XV, that courageous prophet of peace, who guided the Church through turbulent times of war. In his footsteps I place my ministry in the service of reconciliation and harmony between peoples."

See also

Notes

- Psalm 71:1.

- James Paul John Baptist of the Church.

References

- "Miranda, Salvador. "Della Chiesa, Giacomo", The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church, Florida International University". Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "CHIESA 1922 GENNAIO". Araldicavaticana.com. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- Franzen 380

- Franzen 382

- AAS 1921, 345

- "Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, aka Pope Benedict XV". www.familysearch.org. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- George L. Williams, Papal Genealogy: The Families and Descendants of the Popes (2004:133)

- Salvador Miranda. "Consistory of March 27, 1882 (IV)". The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- Pollard, John F. (2000). The Unknown Pope: Benedict XV, 1914–1922 and the Pursuit of Peace. p. 2.

- De Waal 14–15

- Pollard 15

- De Waal 68

- "The New Pope", The Wall Street Journal, 4 September 1914, p. 3. (Newspapers.com)

- De Waal 70

- De Waal 82

- De Waal 102

- De Waal 100

- De Waal 121

- 1913

- De Waal 110

- De Waal 117

- De Waal 124

- Note on numbering: Pope Benedict X is now considered an antipope. At the time, however, this status was not recognized, and so the man the Catholic Church officially considers the tenth true Pope Benedict took the official number XI, rather than X. This has advanced the numbering of all subsequent Popes Benedict by one. Popes Benedict XI-XVI are, from an official point of view, the tenth through fifteenth popes by that name. In other words, there is no legitimate Pope Benedict X.

- John Paul Adams (2007). "Sede Vacante 1914". Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- "Benedict XV 100 years after his death: the pacifist pope". Ruetir. 20 January 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Terry Philpot (19 July 2014). "World War I's Pope Benedict XV and the pursuit of peace". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved 18 February 2022.

- Conrad Gröber, Handbuch der Religiösen Gegenwartsfragen, Herder Freiburg, DE 1937, 493

- Gröber 495

- Pollard, 136

- Youssef Taouk, 'The Pope's Peace Note of 1917: the British response', Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 37 (2) (2016) Archived 26 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine, 193–207.

- John R. Smestad Jr., 'Europe 1914–1945: Attempts at Peace' Archived 8 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Loyola University New Orleans The Student Historical Journal 1994–1995 Vol XXVI.

- Five of seven points of Benedict XV's peace plan, Brigham Young university.

- "Pope in New Note to Ban Conscription," New York Times, 23 September 1917, A1.

- "Pope would clinch peace. Urges abolition of conscription as way to disarmament, New York Times, 16 November 1921, from Associated Press report.

- Pope's Name Pays Homage To Benedict XV, Took Inspiration From An Anti-War Pontiff, WCBSTV, 20 April 2005.

- "Prayer for Peace from Pope Benedict". Chicago Tribune. 14 March 1915. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Pollard 114

- Pollard 113

- Pollard 115

- Pollard 116

- Pollard 141 ff

- DEI MUNUS PULCHERRIMUM ENCYCLICAL OF POPE BENEDICT XV ON PEACE AND CHRISTIAN RECONCILIATION TO THE PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHOPS, AND ORDINARIES IN PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE HOLY SEE

- Pollard 144

- Pollard, 145

- Pollard 145

- Pollard 147

- Pollard 163

- Pollard 173

- Pollard 174

- "Storia del P.I.O." Orientale (in Italian). Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Franzen 381,

- Schmidlin III, 305

- Schmidlin III, 306.

- Schmidlin III, 306

- Schmidlin III, 307

- AAS 1921, 566

- Stehle 25

- Stehle 26

- Schmidlin IV, 15

- Kramer, Martin (12 June 2017). "How the Balfour Declaration Became Part of International Law". Mosaic. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Joseph McAuley (4 September 2015). "When presidents and popes meet: Woodrow Wilson and Benedict XV". America Magazine. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- "Documents on Irish Foreign Policy - Volume 1".

- "Peace conference continues despite furore over de Valera telegram to Vatican". Century Ireland. 25 October 1921. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- "Pope Benedict XV prays for the peace settlement". The Scotsman. 20 October 1921. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- "Catholic world in mourning over death of Pope Benedict XV". Century Ireland. 24 January 1922. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- "Did Benedict XV, 'the Pope of peace', bless the Easter Rising?". The Irish Catholic. 3 January 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- See main article, Ethiopian Catholic Church

- World War One

- AAS 1916 146 Baumann in Marienkunde; 673

- Schmidlin 179–339

- C VII, § 50

- Pope Benedict XV, Bonum Sane, § 4, Vatican, 25 July 1920

- AAS, 1918, 181

- Ad beatissimi Apostolorum, 3

- Ad beatissimi Apostolorum, 4

- (John 14:34);

- (John 15:12);

- Ad beatissimi Apostolorum, 7

- Humani generis redemptionem 2

- Humani generis redemptionem 3

- [Sess., xxiv, De. Ref., c.iv]

- [I Cor. i:17]

- Humani generis redemptionem 7

- Humani generis redemptionem 9

- Quod iam diu, 1

- Quod iam diu, 2

- Maximum illud, 30

- Maximum Illud 30–36

- Maximum illud, 37–40

- "Maximum illud (30 novembre 1919) | BENEDETTO XV". w2.vatican.va. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Miranda, Salvador. "Consistory of December 4, 1916 (II)". The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- Aradi, Zsolt (2017). Pius XI: The Pope and the Man. Pickle Partners Publishing. p. . ISBN 9781787205000. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- Kertzer, David I. (2014). The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871616-7.

- Michael Burleigh, Sacred Causes: The Clash of Religion and Politics from the Great War to the War on Terror, HarperCollins, 2007, p.70.

- De Waal 122

- Pollard 86 ff

- "SEDE VACANTE 1922". www.csun.edu. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "POPE BENEDICT DYING". Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912 - 1954). 21 January 1922. p. 1. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "POPE BENEDICT". Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957). 23 January 1922. p. 7. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "The Houston Post. (Houston, Tex.), Vol. 37, No. 293, Ed. 1 Sunday, January 22, 1922". The Portal to Texas History. 22 January 1922. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- Pio XII, Discorsi, Roma 1939–1958, Vol. VIII, 419

- Discorsi, I 300

- Discorsi, II 346

- Discorsi XIX, 877

- Discorsi XIII,133

- Pope Benedict XVI (27 April 2005). "To Reflect on the Name I Have Chosen". Catholic Culture. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

Sources

- Peters, Walter H. The Life of Benedict XV. 1959. Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company.

- Daughters of St. Paul. Popes of the Twentieth Century. 1983. Pauline Books and Media

- Pollard, John F. The Unknown Pope. 1999. London: Geoffrey Chapman

- Cavagnini, Giovanni and Giulia Grossi (eds.), Benedict XV: A Pope in the World of the 'Useless Slaughter' (1914-1918). 2020. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols

External links

- Vatican website: Benedict XV; texts of encyclicals etc.

- Canonization of Joan of Arc: by Benedict XV

- FirstWorldWar.com: Who's Who

- The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church: Giacomo Della Chiesa

- Pathe News archive film of Benedict XV

- Works by Pope Benedict XV at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Newspaper clippings about Pope Benedict XV in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW