Hans Holbein the Younger

Hans Holbein the Younger (UK: /ˈhɒlbaɪn/ HOL-byne,[2] US: /ˈhoʊlbaɪn, ˈhɔːl-/ HOHL-byne, HAWL-;[3][4][5] German: Hans Holbein der Jüngere; c. 1497[6] – between 7 October and 29 November 1543) was a German-Swiss painter and printmaker who worked in a Northern Renaissance style, and is considered one of the greatest portraitists of the 16th century.[7] He also produced religious art, satire, and Reformation propaganda, and he made a significant contribution to the history of book design. He is called "the Younger" to distinguish him from his father Hans Holbein the Elder, an accomplished painter of the Late Gothic school.

Hans Holbein the Younger | |

|---|---|

| Hans Holbein der Jüngere | |

Self-portrait (c. 1542/43) | |

| Born | c. 1497 |

| Died | October or November 1543 (aged 45–46) |

| Nationality | German,[1] Swiss |

| Known for | Portraits |

| Notable work | The Ambassadors |

| Movement | Northern Renaissance |

| Spouse | Elsbeth Binzenstock |

| Children | Philipp Holbein, Katharina Holbein |

| Parent |

|

| Family | Ambrosius Holbein (brother) |

| Patron(s) | Anne Boleyn, Thomas More |

Holbein was born in Augsburg but worked mainly in Basel as a young artist. At first, he painted murals and religious works, and designed stained glass windows and illustrations for books from the printer Johann Froben. He also painted an occasional portrait, making his international mark with portraits of humanist Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam. When the Reformation reached Basel, Holbein worked for reformist clients while continuing to serve traditional religious patrons. His Late Gothic style was enriched by artistic trends in Italy, France, and the Netherlands, as well as by Renaissance humanism. The result was a combined aesthetic uniquely his own.

Holbein travelled to England in 1526 in search of work with a recommendation from Erasmus. He was welcomed into the humanist circle of Thomas More, where he quickly built a high reputation. He returned to Basel for four years, then resumed his career in England in 1532 under the patronage of Anne Boleyn and Thomas Cromwell. By 1535, he was King's Painter to Henry VIII of England. In this role, he produced portraits and festive decorations, as well as designs for jewellery, plate, and other precious objects. His portraits of the royal family and nobles are a record of the court in the years when Henry was asserting his supremacy over the Church of England.

Holbein's art was prized from early in his career. French poet and reformer Nicholas Bourbon (the elder) dubbed him "the Apelles of our time", a typical accolade at the time.[8] Holbein has also been described as a great "one-off" in art history since he founded no school.[9] Some of his work was lost after his death, but much was collected and he was recognized among the great portrait masters by the 19th century. Recent exhibitions have also highlighted his versatility. He created designs ranging from intricate jewellery to monumental frescoes.

Holbein's art has sometimes been called realist, since he drew and painted with a rare precision. His portraits were renowned in their time for their likeness, and it is through his eyes that many famous figures of his day are pictured today, such as Erasmus and More. He was never content with outward appearance, however; he embedded layers of symbolism, allusion, and paradox in his art, to the lasting fascination of scholars. In the view of art historian Ellis Waterhouse, his portraiture "remains unsurpassed for sureness and economy of statement, penetration into character, and a combined richness and purity of style."[10]

Biography

Early career

_St-Johanns-Vorstadt_22_in_Basel.jpg.webp)

Holbein was born in the free imperial city of Augsburg during the winter of 1497–98.[11] He was a son of the painter and draughtsman Hans Holbein the Elder, whose trade he and his older brother, Ambrosius, followed. Holbein the Elder ran a large and busy workshop in Augsburg, sometimes assisted by his brother Sigmund, also a painter.[12]

By 1515, Hans and Ambrosius had moved as journeymen painters to the city of Basel, a centre of learning and the printing trade.[13] There they were apprenticed to Hans Herbster, Basel's leading painter.[14] The brothers found work in Basel as designers of woodcuts and metalcuts for printers.[15] In 1515, the preacher and theologian Oswald Myconius invited them to add pen drawings to the margin of a copy of The Praise of Folly by the humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam.[16] The sketches provide early evidence of Holbein's wit and humanistic leaning. His other early works, including the double portrait of Basel's mayor Jakob Meyer zum Hasen and his wife Dorothea, follow his father's style.[17] With Meyer zum Hasen, Holbein maintained a close working relationship until the latter was sacked in 1521.[18]

The young Holbein, alongside his brother and his father, is pictured in the left-hand panel of Holbein the Elder's 1504 altar piece triptych the Basilica of St. Paul, which is displayed at the Staatsgalerie in Augsburg.[19]

In 1517, father and son began a project in Lucerne (Luzern), painting internal and external murals for the merchant Jakob von Hertenstein.[20] While in Lucerne, Holbein also designed cartoons for stained glass.[21] The city's records show that on 10 December 1517, he was fined five livres for fighting in the street with a goldsmith called Caspar, who was fined the same amount.[22] That winter, Holbein probably visited northern Italy, though no record of the trip survives. Many scholars believe he studied the work of Italian masters of fresco, such as Andrea Mantegna, before returning to Lucerne.[23] He filled two series of panels at Hertenstein's house with copies of works by Andrea Mantegna, including The Triumphs of Caesar.[24]

In 1519, Holbein moved back to Basel. His brother fades from the record at about this time, and it is usually presumed that he died.[25] Holbein re-established himself rapidly in the city, running a busy workshop. He joined the painters' guild and took out Basel citizenship.[26] He married Elsbeth Binsenstock-Schmid 1519,[27] a widow a few years older than he was, who had an infant son, Franz, and was running her late husband's tanning business. She bore Holbein a son of his own, Philipp, in their first year of marriage[28] a girl called Katharina in 1526 and two more children, Jacob and Küngold in later years.[27]

Holbein was prolific during this period in Basel, which coincided with the arrival of Lutheranism in the city.[29] He undertook a number of major projects, such as external murals for The House of the Dance and internal murals for the Council Chamber of the Town Hall. The former are known from preparatory drawings.[30] The Council Chamber murals survive in a few poorly preserved fragments.[31] Holbein also produced a series of religious paintings and designed cartoons for stained glass windows.[32]

In a period of a revolution in book design, he illustrated for the publisher Johann Froben. His woodcut designs included those for the Dance of Death,[33] cut by the formschneider Hans Lützelburger[34] the Icones (illustrations of the Old Testament),[35] and the title page of Martin Luther's bible.[36] Additionally he designed twelve alphabets, of those a Greek and Latin for Froben.[34] The letters were ornamented with depictions of Greek and Roman gods, heads of Caesars, poets and philosophers.[37] Through the woodcut medium, Holbein refined his grasp of expressive and spatial effects.[38]

Holbein also painted the occasional portrait in Basel, among them the double portrait of Jakob and Dorothea Meyer, and, in 1519, that of the young academic Bonifacius Amerbach. According to art historian Paul Ganz, the portrait of Amerbach marks an advance in his style, notably in the use of unbroken colours.[39] For Meyer, he painted an altarpiece of the Madonna which included portraits of the donor, his wife, and his daughter.[40] In 1523, Holbein painted his first portraits of the great Renaissance scholar Erasmus, who required likenesses to send to his friends and admirers throughout Europe.[41] These paintings made Holbein an international artist. Holbein visited France in 1524, probably to seek work at the court of Francis I.[42] When Holbein decided to seek employment in England in 1526, Erasmus recommended him to his friend the statesman and scholar Thomas More.[43] "The arts are freezing in this part of the world," he wrote, "and he is on the way to England to pick up some angels".[44]

England, 1526–1528

Holbein broke his journey towards Antwerp, where he delivered a recommendation from Erasmus to Pieter Gillis.[45] In Antwerp, he also bought some oak panels and may have met the painter Quentin Matsys.[46] Gillis then seemed to have sent Holbein to the Court of England,[45] where Sir Thomas More welcomed him to and found him a series of commissions. "Your painter, my dearest Erasmus," he wrote, "is a wonderful artist".[47][45] Holbein painted the famous Portrait of Sir Thomas More and another of More with his family. The group portrait, original in conception, is known only from a preparatory sketch and copies by other hands.[48] According to art historian Andreas Beyer, it "offered a prelude of a genre that would only truly gain acceptance in Dutch painting of the seventeenth century".[49] Seven fine-related studies of More family members also survive.[50]

During this first stay in England, Holbein worked largely for a humanist circle with ties to Erasmus. Among his commissions was the portrait of William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury, who owned a Holbein portrait of Erasmus.[51] Holbein also painted the Bavarian astronomer and mathematician Nicholas Kratzer, a tutor of the More family whose notes appear on Holbein's sketch for their group portrait.[52] Although Holbein did not work for the king during this visit, he painted the portraits of courtiers such as Sir Henry Guildford and his wife Lady Mary,[53] and of Anne Lovell, identified in 2003 or 2004[54] as the subject of Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling.[55] In May 1527, "Master Hans" also painted a panorama of the siege of Thérouanne for the visit of French ambassadors. With Kratzer, he devised a ceiling covered in planetary signs, under which the visitors dined.[56] The chronicler Edward Hall described the spectacle as showing "the whole Earth, environed with the sea, like a very map or cart".[57]

Basel, 1528–1532

In August 1528, Holbein bought a house in Basel in St.Johanns-Vorstadt and became the neighbor of Hieronymus Froben.[58] For this house he paid a third in advance.[58] He presumably returned home to preserve his citizenship, since he had been granted only a two-year leave of absence.[59] Enriched by his success in England, Holbein bought a second neighboring house in 1531[60] for which he initially advanced only a seventh of the price and was to pay a yearly rate during the following six years.[58]

During this period in Basel, he painted The Artist's Family, showing Elsbeth with the couple's two eldest children, Philipp and Katherina, evoking images of the Virgin and Child with St John the Baptist.[61] Art historian John Rowlands sees this work as "one of the most moving portraits in art, from an artist, too, who always characterized his sitters with a guarded restraint".[62]

Basel had become a turbulent city in Holbein's absence. Reformers, swayed by the ideas of Zwingli, carried out acts of iconoclasm and banned imagery in churches. In April 1529, the free-thinking Erasmus felt obliged to leave his former haven for Freiburg im Breisgau.[63] The iconoclasts probably destroyed some of Holbein's religious artwork,[64] though the paintings on the organ doors of the Basel Minster were saved.[58][65] Evidence for Holbein's religious views is fragmentary and inconclusive. "The religious side of his paintings had always been ambiguous," suggests art historian John North, "and so it remained".[66] According to a register compiled to ensure that all major citizens subscribed to the new doctrines: "Master Hans Holbein, the painter, says that we must be better informed about the [holy] table before approaching it".[67] In 1530, the authorities called Holbein to account for failing to attend the reformed communion.[68] Shortly afterwards, however, he was listed among those "who have no serious objections and wish to go along with other Christians".[69]

Holbein evidently retained favour under the new order. The reformist council paid him a retaining fee of 50 florins and commissioned him to resume work on the Council Chamber frescoes. They now chose themes from the Old Testament instead of the previous stories from classical history and allegory. Holbein's frescoes of Rehoboam and of the meeting between Saul and Samuel were more simply designed than their predecessors.[70] Holbein worked for traditional clients at the same time. His old patron Jakob Meyer paid him to add figures and details to the family altarpiece he had painted in 1526. Holbein's last commission in this period was the decoration of two clock faces on the city gate in 1531.[62] The reduced levels of patronage in Basel may have prompted his decision to return to England early in 1532.[71]

England, 1532–1540

Holbein returned to England, where the political and religious environment was changing radically.[72] In 1532, Henry VIII was preparing to repudiate Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn, in defiance of the pope.[73] Among those who opposed Henry's actions was Holbein's former host and patron Sir Thomas More, who resigned as Lord Chancellor in May 1532. Around this time, Holbein is supposed to have decorated the mortuary roll of John Islip, abbot of Westminster, one of the last mortuary rolls created.[74] Holbein seems to have distanced himself from More's humanist milieu on this visit, and "he deceived those to whom he was recommended", according to Erasmus.[75] The artist found favour instead within the radical new power circles of the Boleyn family and Thomas Cromwell. Cromwell became the king's secretary in 1534, controlling all aspects of government, including artistic propaganda.[76] More was executed in 1535 along with John Fisher, whose portrait Holbein had also drawn.[77]

Holbein's commissions in the early stages of his second English period included portraits of Lutheran merchants of the Hanseatic League. The merchants lived and plied their trade at the Steelyard, a complex of warehouses, offices, and dwellings on the north bank of the Thames. Holbein rented a house in Maiden Lane nearby, and he portrayed his clients in a range of styles. His portrait of Georg Giese of Gdańsk shows the merchant surrounded by exquisitely painted symbols of his trade. His portrait of Derich Berck of Cologne, on the other hand, is classically simple and possibly influenced by Titian.[78] For the guildhall of the Steelyard, Holbein painted the monumental allegories The Triumph of Wealth and The Triumph of Poverty, both now lost. The merchants also commissioned a street tableau of Mount Parnassus for Anne Boleyn's coronation eve procession of 31 May 1533.[79]

Holbein also portrayed various courtiers, landowners, and visitors during this time, and his most famous painting of the period was The Ambassadors. This life-sized panel portrays Jean de Dinteville, an ambassador of Francis I of France in 1533, and Georges de Selve, Bishop of Lavaur who visited London the same year.[80] The work incorporates symbols and paradoxes, including an anamorphic (distorted) skull. According to scholars, these are enigmatic references to learning, religion, mortality, and illusion in the tradition of the Northern Renaissance.[81] Art historians Oskar Bätschmann and Pascal Griener suggest that in The Ambassadors, "Sciences and arts, objects of luxury and glory, are measured against the grandeur of Death".[82]

No certain portraits survive of Anne Boleyn by Holbein, perhaps because her memory was purged following her execution for treason, incest, and adultery in 1536.[83] It is clear, however, that Holbein worked directly for Anne and her circle.[84] He designed a cup engraved with her device of a falcon standing on roses, as well as jewellery and books connected to her. He also sketched several women attached to her entourage, including her sister-in-law Jane Parker.[85] At the same time, Holbein worked for Thomas Cromwell as he masterminded Henry VIII's reformation. Cromwell commissioned Holbein to produce reformist and royalist images, including anti-clerical woodcuts and the title page to Myles Coverdale's English translation of the Bible. Henry VIII had embarked on a grandiose programme of artistic patronage. His efforts to glorify his new status as Supreme Head of the Church culminated in the building of Nonsuch Palace, which started in 1538.[86]

By 1536, Holbein was employed as the King's Painter on an annual salary of 30 pounds—though he was never the highest-paid artist on the royal payroll.[87] Royal "pictor maker" Lucas Horenbout earned more, and other continental artists also worked for the king.[88] In 1537, Holbein painted his most famous image: Henry VIII standing in a heroic pose with his feet planted apart.[89] The left section has survived of Holbein's cartoon for a life-sized wall painting at Whitehall Palace showing the king in this pose with his father behind him. The mural also depicted Jane Seymour and Elizabeth of York, but it was destroyed by fire in 1698. It is known from engravings and from a 1667 copy by Remigius van Leemput.[90] An earlier half-length portrait shows Henry in a similar pose,[91] but all the full-length portraits of him are copies based on the Whitehall pattern.[92] The figure of Jane Seymour in the mural is related to Holbein's sketch and painting of her.[93]

Jane died in October 1537, shortly after bearing Henry's only legitimate son Edward VI, and Holbein painted a portrait of the infant prince about two years later, clutching a sceptre-like gold rattle.[94] Holbein's final portrait of Henry dates from 1543 and was perhaps completed by others, depicting the king with a group of barber surgeons.[95]

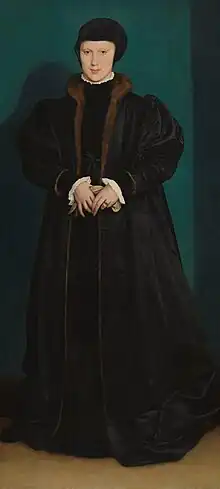

Holbein's portrait style altered after he entered Henry's service. He focused more intensely on the sitter's face and clothing, largely omitting props and three-dimensional settings.[96] He applied this clean, craftsman-like technique to miniature portraits such as that of Jane Small, and to grand portraits such as that of Christina of Denmark. He travelled with Philip Hoby to Brussels in 1538 and sketched Christina for the king, who was appraising the young widow as a prospective bride.[97] John Hutton, the English ambassador in Brussels, reported that another artist's drawing of Christina was "sloberid" (slobbered) compared to Holbein's.[98]

In Wilson's view, Holbein's subsequent oil portrait is "the loveliest painting of a woman that he ever executed, which is to say that it is one of the finest female portraits ever painted".[99] The same year, Holbein and Hoby went to France to paint Louise of Guise and Anna of Lorraine for Henry VIII. Neither portrait of these cousins has survived.[100] Holbein found time to visit Basel, where he was fêted by the authorities and granted a pension.[101] On the way back to England, he apprenticed his son Philipp to Basel-born goldsmith Jacob David in Paris.[102]

.jpg.webp)

Holbein painted Anne of Cleves at Burgau Castle, posing her square-on and in elaborate finery. This was the woman whom Henry married at Düren at the encouragement of Thomas Cromwell in the summer of 1539.[103] English envoy Nicholas Wotton reported that "Hans Holbein hath taken the effigies of my Lady Anne and the lady Amelia [Anne's sister] and hath expressed their images very lively".[104] Henry was disillusioned with Anne in the flesh, however, and he divorced her after a brief, unconsummated marriage. There is a tradition that Holbein's portrait flattered Anne, derived from the testimony of Sir Anthony Browne.

Henry said that he was dismayed by her appearance at Rochester, having seen her pictures and heard advertisements of her beauty—so much that his face fell.[105] No one other than Henry ever described Anne as repugnant; French Ambassador Charles de Marillac thought her quite attractive, pleasant, and dignified, though dressed in unflattering, heavy German clothing, as were her attendants.[106][107] Some of the blame for the king's disillusionment fell on Thomas Cromwell, who had been instrumental in arranging the marriage and had passed on some exaggerated claims of Anne's beauty.[108] This was one of the factors that led to Cromwell's downfall.[109]

Last years and death, 1540–1543

Holbein had deftly survived the downfall of his first two great patrons, Thomas More and Anne Boleyn, but Cromwell's sudden arrest and execution on trumped-up charges of heresy and treason in 1540 undoubtedly damaged his career.[110] Though Holbein retained his position as King's Painter, Cromwell's death left a gap no other patron could fill. It was, ironically, Holbein's portrait of Anne of Cleves which largely led to Cromwell's downfall: furious at being saddled with a wife he found entirely unattractive, the King directed all his anger at Cromwell. Granted, Cromwell had exaggerated her beauty,[111] but there is no evidence that Henry blamed Holbein for supposedly flattering Anne's looks.

Apart from routine official duties, Holbein now occupied himself with private commissions, turning again to portraits of Steelyard merchants. He also painted some of his finest miniatures, including those of Henry Brandon and Charles Brandon, sons of Henry VIII's friend Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk and his fourth wife, Catherine Willoughby. Holbein managed to secure commissions among those courtiers who now jockeyed for power, in particular from Anthony Denny, one of the two chief gentlemen of the bedchamber. He became close enough to Denny to borrow money from him.[113] He painted Denny's portrait in 1541 and two years later designed a clock-salt for him. Denny was part of a circle that gained influence in 1542 after the failure of Henry's marriage to Catherine Howard. The king's marriage in July 1543 to the reformist Catherine Parr, whose brother Holbein had painted in 1541, established Denny's party in power.

Holbein may have visited his wife and children in late 1540, when his leave of absence from Basel expired. None of his work dates from this period, and the Basel authorities paid him six months' salary in advance.[114] The state of Holbein's marriage has intrigued scholars, who base their speculations on fragmentary evidence. Apart from one brief visit, Holbein had lived apart from Elsbeth since 1532. His will reveals that he had two infant children in England, of whom nothing is known except that they were in the care of a nurse.[115]

Holbein's unfaithfulness to Elsbeth may not have been new. Some scholars believe that Magdalena Offenburg, the model for the Darmstadt Madonna and for two portraits painted in Basel, was for a time Holbein's mistress.[116] Others dismiss the idea.[117] One of the portraits was of Lais of Corinth, mistress of Apelles, the famous artist of Greek antiquity after whom Holbein was named in humanist circles.[118] Whatever the case, it is likely that Holbein always supported his wife and children.[119] When Elsbeth died in 1549, she was well off and still owned many of Holbein's fine clothes; on the other hand, she had sold his portrait of her before his death.[120]

Hans Holbein died between 7 October and 29 November 1543 at the age of 45.[121] Karel van Mander stated in the early 17th century that he died of the plague. Wilson regards the story with caution since Holbein's friends attended his bedside; and Peter Claussen suggests that he died of an infection.[122] Describing himself as "servant to the king's majesty", Holbein made his will on 7 October at his home in Aldgate. The goldsmith John of Antwerp and a few German neighbours signed as witnesses.[123]

Holbein may have been in a hurry, because the will was not witnessed by a lawyer. On 29 November, John of Antwerp, the subject of several of Holbein's portraits, legally undertook the administration of the artist's last wishes. He presumably settled Holbein's debts, arranged for the care of his two children, and sold and dispersed his effects, including many designs and preliminary drawings that have survived.[124] The site of Holbein's grave is unknown and may never have been marked. The churches of St Katherine Cree or St Andrew Undershaft in London are possible locations, being located near his house.[125]

Art

Influences

The first influence on Holbein was his father, Hans Holbein the Elder, an accomplished religious artist and portraitist[126] who passed on his techniques as a religious artist and his gifts as a portraitist to his son.[127] The young Holbein learned his craft in his father's workshop in Augsburg, a city with a thriving book trade, where woodcut and engraving flourished. Augsburg also acted as one of the chief "ports of entry" into Germany for the ideas of the Italian Renaissance.[128] By the time Holbein began his apprenticeship under Hans Herbster in Basel, he was already steeped in the late Gothic style, with its unsparing realism and emphasis on line, which influenced him throughout his life.[129] In Basel, he was favoured by humanist patrons, whose ideas helped form his vision as a mature artist.[130]

During his Swiss years, when he may have visited Italy, Holbein added an Italian element to his stylistic vocabulary. Scholars note the influence of Leonardo da Vinci's "sfumato" (smoky) technique on his work, for example in his Lais of Corinth.[131] From the Italians, Holbein learned the art of single-point perspective and the use of antique motifs and architectural forms. In this, he may have been influenced by Andrea Mantegna.[132] The decorative detail recedes in his late portraits, though the calculated precision remains. Despite assimilating Italian techniques and Reformation theology, Holbein's art in many ways extended the Gothic tradition.[133]

His portrait style, for example, remained distinct from the more sensuous technique of Titian, and from the Mannerism of William Scrots, Holbein's successor as King's Painter.[134] Holbein's portraiture, particularly his drawings, had more in common with that of Jean Clouet, which he may have seen during his visit to France in 1524.[135] He adopted Clouet's method of drawing with coloured chalks on a plain ground, as well as his care over preliminary portraits for their own sake.[136] During his second stay in England, Holbein learned the technique of limning, as practised by Lucas Horenbout. In his last years, he raised the art of the portrait miniature to its first peak of brilliance.[137]

Religious works

Holbein followed in the footsteps of Augsburg artists like his father and Hans Burgkmair, who largely made their living from religious commissions. Despite calls for reform, the church in the late 15th century was medieval in tradition. It maintained an allegiance to Rome and a faith in pieties such as pilgrimages, veneration of relics, and prayer for dead souls. Holbein's early work reflects this culture. The growing reform movement, led by humanists such as Erasmus and Thomas More, began, however, to change religious attitudes. Basel, where Martin Luther's major works were first published, became the main centre for the transmission of Reformation ideas.[138]

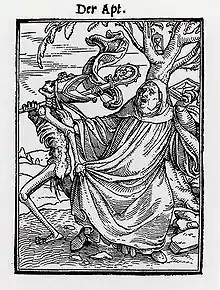

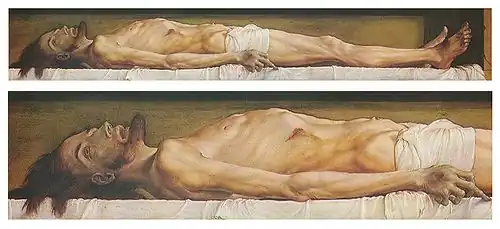

The gradual shift from traditional to reformed religion can be charted in Holbein's work. His Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb of 1522 expresses a humanist view of Christ in tune with the reformist climate in Basel at the time.[139] The Dance of Death (1523–26) refashions the late-medieval allegory of the Danse Macabre as a reformist satire.[140] Holbein's series of woodcuts shows the figure of "Death" in many disguises, confronting individuals from all walks of life. None escape Death's skeleton clutches, even the pious.[141]

In addition to the Dance of Death Holbein completed Icones or Series of the Old Gospel (It contains two works: The images of the stories of the Old Gospel and Portraits or printing boards of the story of the Old Gospel). These works were arranged by Holbein with Melchior & Gaspar Trechsel in about 1526, later printed and edited in Latin by Jean & Francois Frellon with 92 woodcuts. These two works also share the first four figures with the Dance of Death.

It appears that the Trechsel brothers initially intended to hire Holbein for illustrating Bibles.[142] In fact, some of Holbein's Icones woodcuts appear in the recently discovered Biblia cum Glossis[143] by Michel De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus). Holbein woodcuts appear in several other works by Servetus: his Spanish translation of The images of the stories of the Old Gospel,[144] printed by Juan Stelsio in Antwerp in 1540 (92 woodcuts), and also of his Spanish versification of the associated work Portraits or printing boards of the story of the Old Gospel, printed by Francois and Jean Frellon in 1542 (same 92 woodcuts plus 2 more), as it was demonstrated in the International Society for the History of Medicine, by the expert researcher in Servetus, González Echeverría, who also proved the existence of the other work of Holbein & De Villeneuve, Biblia cum Glossis or " Lost Bible".[145][146]

Holbein painted many large religious works between 1520 and 1526, including the Oberried Altarpiece, the Solothurn Madonna, and the Passion. Only when Basel's reformers turned to iconoclasm in the later 1520s did his freedom and income as a religious artist suffer.[147]

Holbein continued to produce religious art, but on a much smaller scale. He designed satirical religious woodcuts in England. His small painting for private devotion, Noli Me Tangere,[148] has been taken as an expression of his personal religion. Depicting the moment when the risen Christ tells Mary Magdalene not to touch him, Holbein adheres to the details of the bible story.[149] The 17th-century diarist John Evelyn wrote that he "never saw so much reverence and kind of heavenly astonishment expressed in a picture".[150]

Holbein has been described as "the supreme representative of German Reformation art".[66] The Reformation was a varied movement, however, and his position was often ambiguous. Despite his ties with Erasmus and More, he signed up to the revolution begun by Martin Luther, which called for a return to the Bible and the overthrow of the papacy. In his woodcuts Christ as the Light of the World and The Selling of Indulgences, Holbein illustrated attacks by Luther against Rome.[151] At the same time, he continued to work for Erasmians and known traditionalists. After his return from England to a reformed Basel in 1528, he resumed work both on Jakob Meyer's Madonna and on the murals for the Council Chamber of the Town Hall. The Madonna was an icon of traditional piety, while the Old Testament murals illustrated a reformist agenda.

Holbein returned to England in 1532 as Thomas Cromwell was about to transform religious institutions there. He was soon at work for Cromwell's propaganda machine, creating images in support of the royal supremacy.[152] During the period of the Dissolution of the Monasteries, he produced a series of small woodcuts in which biblical villains were dressed as monks.[153] His reformist painting The Old and the New Law Archived 25 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine identified the Old Testament with the "Old Religion".[154] Scholars have detected subtler religious references in his portraits. In The Ambassadors, for example, details such as the Lutheran hymn book and the crucifix behind the curtain allude to the context of the French mission.[155] Holbein painted few religious images in the later part of his career.[156] He focused on secular designs for decorative objects, and on portraits stripped of inessentials.

Portraits

For Holbein, "everything began with a drawing".[157] A gifted draughtsman, he was heir to a German tradition of line drawing and precise preparatory design. Holbein's chalk and ink portraits demonstrate his mastery of outline. He always made preparatory portraits of his sitters, though many drawings survive for which no painted version is known, suggesting that some were drawn for their own sake.[158] Holbein produced relatively few portraits during his years in Basel. Among these were his 1516 studies of Jakob and Dorothea Meyer, sketched, like many of his father's portrait drawings, in silverpoint and chalk.[159]

Holbein painted most of his portraits during his two periods in England. In the first, between 1526 and 1528, he used the technique of Jean Clouet for his preliminary studies, combining black and coloured chalks on unprimed paper. In the second, from 1532 to his death, he drew on smaller sheets of pink-primed paper, adding pen and brushwork in ink to the chalk.[160] Judging by the three-hour sitting given to him by Christina of Denmark, Holbein could produce such portrait studies quickly.[157] Some scholars believe that he used a mechanical device to help him trace the contours of his subjects' faces.[161] Holbein paid less attention to facial tones in his later drawings, making fewer and more emphatic strokes, but they are never formulaic.[162] His grasp of spatial relationships ensures that each portrait, however sparely drawn, conveys the sitter's presence.[163]

Holbein's painted portraits were closely founded on drawing. Holbein transferred each drawn portrait study to the panel with the aid of geometrical instruments.[164] He then built up the painted surface in tempera and oil, recording the tiniest detail, down to each stitch or fastening of costume. In the view of art historian Paul Ganz, "The deep glaze and the enamel-like lustre of the colouring were achieved by means of the metallic, highly polished crayon groundwork, which admitted of few corrections and, like the preliminary sketch, remained visible through the thin layer of colour".[164]

The result is a brilliant portrait style in which the sitters appear, in Foister's words, as "recognisably individual and even contemporary-seeming" people, dressed in minutely rendered clothing that provides an unsurpassed source for the history of Tudor costume.[165] Holbein's humanist clients valued individuality highly.[166] According to Strong, his portrait subjects underwent "a new experience, one which was a profound visual expression of humanist ideals".[167]

Commentators differ in their response to Holbein's precision and objectivity as a portraitist. What some see as an expression of spiritual depth in his sitters, others have called mournful, aloof, or even vacant. "Perhaps an underlying coolness suffuses their countenances," wrote Holbein's 19th-century biographer Alfred Woltmann, "but behind this outward placidness lies hidden a breadth and depth of inner life".[168] Some critics see the iconic and pared-down style of Holbein's later portraits as a regression. Kenyon Cox, for example, believes that his methods grew more primitive, reducing painting "almost to the condition of medieval illumination".[169] Erna Auerbach relates the "decorative formal flatness" of Holbein's late art to the style of illuminated documents, citing the group portrait of Henry VIII and the Barber Surgeons' Company.[170] Other analysts detect no loss of powers in Holbein's last phase.[171]

Until the later 1530s, Holbein often placed his sitters in a three-dimensional setting. At times, he included classical and biblical references and inscriptions, as well as drapery, architecture, and symbolic props. Such portraits allowed Holbein to demonstrate his virtuosity and powers of allusion and metaphor, as well as to hint at the private world of his subjects. His 1532 portrait of Sir Brian Tuke, for example, alludes to the sitter's poor health, comparing his sufferings to those of Job. The depiction of the Five wounds of Christ and the inscription "INRI" on Tuke's crucifix are, according to scholars Bätschmann and Griener, "intended to protect its owner against ill-health".[172] Holbein portrays the merchant Georg Gisze among elaborate symbols of science and wealth that evoke the sitter's personal iconography. However, some of Holbein's other portraits of Steelyard merchants, for example that of Derich Born, concentrate on the naturalness of the face. They prefigure the simpler style that Holbein favoured in the later part of his career.[173]

Study of Holbein's later portraits has been complicated by the number of copies and derivative works attributed to him. Scholars now seek to distinguish the true Holbeins by the refinement and quality of the work.[174] The hallmark of Holbein's art is a searching and perfectionist approach discernible in his alterations to his portraits. In the words of art historian John Rowlands:

This striving for perfection is very evident in his portrait drawings, where he searches with his brush for just the right line for the sitter's profile. The critical faculty in making this choice and his perception of its potency in communicating decisively the sitter's character is a true measure of Holbein's supreme greatness as a portrait painter. Nobody has ever surpassed the revealing profile and stance in his portraits: through their telling use, Holbein still conveys across the centuries the character and likeness of his sitters with unrivalled mastery.[175]

Miniatures

_-_Mrs_Jane_Small%252C_formerly_Mrs_Pemberton_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

During his last decade, Holbein painted a number of miniatures, which are small portraits worn as a kind of jewel. His miniature technique derived from the medieval art of manuscript illumination. His small panel portrait of Henry VIII shows an interpenetration between his panel and miniature painting.[176] Holbein's large pictures had always contained a miniature-like precision. He now adapted this skill to the smaller form, somehow retaining a monumental effect.[177] The twelve or so certain miniatures by Holbein that survive reveal his mastery of "limning", as the technique was called.[178]

His miniature portrait of Jane Small, with its rich blue background, crisp outlines, and absence of shading, is considered a masterpiece of the genre. According to art historian Graham Reynolds, Holbein "portrays a young woman whose plainness is scarcely relieved by her simple costume of black-and-white materials, and yet there can be no doubt that this is one of the great portraits of the world. With remarkable objectivity Holbein has not added anything of himself or subtracted from his sitter's image; he has seen her as she appeared in a solemn mood in the cold light of his painting-room".[179]

Designs

Throughout his life, Holbein designed both large-scale decorative works such as murals and smaller objects, including plate and jewellery. In many cases, his designs, or copies of them, are the sole evidence for such works. For example, his murals for the Hertenstein House in Lucerne and for the House of the Dance in Basel are known only through his designs. As his career progressed, he added Italian Renaissance motifs to his Gothic vocabulary.

Many of the intricate designs etched into suits of Greenwich armour, including King Henry's own personal tournament harnesses, were based on designs by Holbein. His style continued to influence the unique form of English armour for nearly half a century after his death.

Holbein's cartoon for part of the dynastic Tudor wall painting at Whitehall reveals how he prepared for a large mural. It was made of 25 pieces of paper, each figure cut out and pasted onto the background.[180] Many of Holbein's designs for glass painting, metalwork, jewellery, and weapons also survive. All demonstrate the precision and fluidity of his draughtsmanship. In the view of art historian Susan Foister, "These qualities so animate his decorative designs, whether individual motifs, such as his favoured serpentine mermen and women, or the larger shapes of cups, frames, and fountains, that they scintillate on paper even before their transformation into precious metal and stone".[163]

Holbein's way of designing objects was to sketch preliminary ideas and then draw successive versions with increasing precision. His final draft was a presentation version. He often used traditional patterns for ornamental details such as foliage and branches. When designing precious objects, Holbein worked closely with craftsmen such as goldsmiths including Cornelis Hayes. His design work, suggests art historian John North, "gave him an unparalleled feel for the textures of materials of all kinds, and it also gave him the habit of relating physical accessories to face and personality in his portraiture".[181] Although little is known of Holbein's workshop, scholars assume that his drawings were partly intended as sources for his assistants.

Legacy and reputation

Holbein's fame owes something to that of his sitters. Several of his portraits have become cultural icons.[182] He created the standard image of Henry VIII.[183] In painting Henry as an iconic hero, however, he also subtly conveyed the tyranny of his character.[184] Holbein's portraits of other historical figures, such as Erasmus, Thomas More, and Thomas Cromwell, have fixed their images for posterity. The same is true for the array of English lords and ladies whose appearance is often known only through his art. For this reason, John North calls Holbein "the cameraman of Tudor history".[185] In Germany, on the other hand, Holbein is regarded as an artist of the Reformation, and in Europe of humanism.[186]

In Basel, Holbein's legacy was secured by his friend Amerbach and by Amerbach's son Basilius, who collected his work. The Amerbach-Kabinett later formed the core of the Holbein collection at the Kunstmuseum Basel.[187] Although Holbein's art was also valued in England, few 16th-century English documents mention him. Archbishop Matthew Parker (1504–75) observed that his portraits were "delineated and expressed to the resemblance of life".[188] At the end of the 16th century, the miniature portraitist Nicholas Hilliard spoke in his treatise Arte of Limning of his debt to Holbein: "Holbein's manner have I ever imitated, and hold it for the best".[189] No account of Holbein's life was written until Karel van Mander's often inaccurate "Schilder-Boeck" (Painter-Book) of 1604.[190]

Holbein's followers produced copies and versions of his work, but he does not seem to have founded a school.[191] Biographer Derek Wilson calls him one of the great "one-offs" of art history.[9] The only artist who appears to have adopted his techniques was John Bettes the Elder, whose Man in a Black Cap (1545) is close in style to Holbein.[192] Scholars differ about Holbein's influence on English art. In Foister's view: "Holbein had no real successors and few imitators in England. The disparity between his subtle, interrogatory portraits of men and women whose gazes follow us, and the stylised portraits of Elizabeth I and her courtiers can seem extreme, the more so as it is difficult to trace a proper stylistic succession to Holbein's work to bridge the middle of the century".[163]

Nevertheless, "modern" painting in England may be said to have begun with Holbein.[193] That later artists were aware of his work is evident in their own, sometimes explicitly. Hans Eworth, for example, painted two full-length copies in the 1560s of Holbein's Henry VIII derived from the Whitehall pattern and included a Holbein in the background of his Mary Neville, Lady Dacre.[194] The influence of Holbein's "monumentality and attention to texture" has been detected in Eworths' work.[195] According to art historian Erna Auerbach: "Holbein's influence on the style of English portraiture was undoubtedly immense. Thanks to his genius, a portrait type was created which both served the requirements of the sitter and raised portraiture in England to a European level. It became the prototype of the English Court portrait of the Renaissance period".[196]

The fashion for Old Masters in England after the 1620s created a demand for Holbein, led by the connoisseur Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel. The Flemish artists Anthony van Dyck and Peter Paul Rubens discovered Holbein through Arundel.[197] Arundel commissioned engravings of his Holbeins from the Czech Wenceslaus Hollar, some of works now lost. From this time, Holbein's art was also prized in the Netherlands, where the picture dealer Michel Le Blon became a Holbein connoisseur.[198] The first catalogue raisonné of Holbein's work was produced by the Frenchman Charles Patin and the Swiss Sebastian Faesch in 1656. They published it with Erasmus's Encomium moriæ (The Praise of Folly) and an inaccurate biography that portrayed Holbein as dissolute.

In the 18th century, Holbein found favour in Europe with those who saw his precise art as an antidote to the Baroque. In England, the connoisseur and antiquarian Horace Walpole (1717–97) praised him as a master of the Gothic.[199] Walpole hung his neo-Gothic house at Strawberry Hill with copies of Holbeins and kept a Holbein room. From around 1780, a re-evaluation of Holbein set in, and he was enshrined among the canonical masters.[200] A new cult of the sacral art masterpiece arose, endorsed by the German Romantics. This view suffered a setback during the famous controversy known as the "Holbein-Streit" (Holbein dispute) in the 1870s. It emerged that the revered Meyer Madonna at Dresden was a copy, and that the little-known version at Darmstadt was the Holbein original.[201] Since then, scholars have gradually removed the attribution to Holbein from many copies and derivative works. The current scholarly view of Holbein's art stresses his versatility, not only as a painter but as a draughtsman, printmaker, and designer.[202] Art historian Erika Michael believes that "the breadth of his artistic legacy has been a significant factor in the sustained reception of his oeuvre".[203]

Gallery

Hans Holbein's witty marginal drawing of Folly (1515), in the first edition, a copy owned by Erasmus himself (Kupferstichkabinett, Basel)

Hans Holbein's witty marginal drawing of Folly (1515), in the first edition, a copy owned by Erasmus himself (Kupferstichkabinett, Basel) The Humiliation of the Emperor Valerian by the Persian King Shapur, c. 1521. Pen and black ink on chalk sketch, grey wash and watercolour, Kunstmuseum Basel

The Humiliation of the Emperor Valerian by the Persian King Shapur, c. 1521. Pen and black ink on chalk sketch, grey wash and watercolour, Kunstmuseum Basel.jpg.webp) Portrait of Bonifacius Amerbach, 1519. Oil and tempera on pine, Kunstmuseum Basel

Portrait of Bonifacius Amerbach, 1519. Oil and tempera on pine, Kunstmuseum Basel The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, and a detail, 1521–22. Oil and tempera on limewood, Kunstmuseum Basel

The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, and a detail, 1521–22. Oil and tempera on limewood, Kunstmuseum Basel Portrait of a Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, c. 1527–28. Oil and tempera on oak, National Gallery, London

Portrait of a Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, c. 1527–28. Oil and tempera on oak, National Gallery, London%253B_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.JPG.webp) Noli me tangere, possibly 1524–26. Oil and tempera on oak, Royal Collection

Noli me tangere, possibly 1524–26. Oil and tempera on oak, Royal Collection Portrait of Jane Seymour, c. 1537. Oil and tempera on oak, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Portrait of Jane Seymour, c. 1537. Oil and tempera on oak, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Portrait of Christina of Denmark, c. 1538. Oil and tempera on oak, National Gallery, London

Portrait of Christina of Denmark, c. 1538. Oil and tempera on oak, National Gallery, London

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Henry Brandon, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, portrait miniature, 1541. Watercolour on vellum, Royal Collection, Windsor Castle

Henry Brandon, 2nd Duke of Suffolk, portrait miniature, 1541. Watercolour on vellum, Royal Collection, Windsor Castle.JPG.webp) Charles Brandon, 3rd Duke of Suffolk, Royal Collection, Windsor Castle

Charles Brandon, 3rd Duke of Suffolk, Royal Collection, Windsor Castle Henry VIII at 49 (1540), Gallerie Nazionali d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome

Henry VIII at 49 (1540), Gallerie Nazionali d'Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, Rome Margaret Roper; c. 1535–36, Bodycolour on vellum mounted on card, 4.5 cm diameter (1.8 in), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Margaret Roper; c. 1535–36, Bodycolour on vellum mounted on card, 4.5 cm diameter (1.8 in), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Notes

- "Hans Holbein the Younger German painter". Encyclopedia Britannica. 22 September 2023.

- "Holbein, Hans". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020.

- "Holbein". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Holbein". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- "Holbein". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- Alastair Armstrong, "Henry VIII: Authority, Nation and Religion 1509–1540"

- Zwingenberger, 9.

- Wilson, 213; Buck, 50, 112. Apelles was a legendary artist of antiquity, whose imitation of nature was thought peerless.

- Wilson, 281.

- Waterhouse, 17.

- Ganz, 1; Wilson, 3. The date is deduced from the age noted by Holbein's father on the portrait of his sons.

- Müller, et al., 6.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 104. Basel had allied itself in 1501 with the Swiss Confederates, a group of cantons that had broken free of imperial rule. Many Basel citizens, however, remained proud of their imperial connections: the Madonna that Holbein painted for Jakob Meyer, for example, wears the imperial crown.

- North, 13–14; Bätschmann and Griener, 11; Claussen, 47. Hans Holbein the Elder and his brother Sigmund also moved away from Augsburg at about this time, but the reasons for the Holbein family's disappointment in the city is not known.

- Sander, 14.

- Zwingenberger, 13; Wilson, 30, 37–42. For example: A Scholar Treads on a Basket of Eggs and Folly Steps Down from the Pulpit.

- Sander, 15. See: Portrait of Jakob Meyer and Portrait of Dorothea Meyer.

- Stein, Wilhelm (1920). Holbein der Jüngere. Berlin: Julius Bard Verlag. p. 29.

- "BBC - Basilica of St Paul by Holbein the Elder - BBC Arts - Paintings featured in Holbein: Eye of the Tudors". BBC.

- See Leaina Before the Judges, a design for a Hertenstein mural.

- Bätschmann and Griener, 11; North, 13. For example: Design for a Stained Glass Window with the Coronation of the Virgin.

- Rowlands, 25; North, 13. On another occasion, Holbein was fined for his involvement in a knife fight.

- Wilson, 53–60; Buck, 20; Bätschmann and Griener, 148; Claussen, 48, 50. Doubt has been cast on the tradition that Holbein visited Italy since artists' biographer Karel van Mander (1548–1606) stated that Holbein never went there. It has been argued by Peter Claussen, for example, that Italian motifs in Holbein's work might have derived from engravings, sculptures, and artworks seen in Augsburg. On the other hand, Bätschmann and Griener quote a document of 1538 in which the Basel authorities gave Holbein permission to sell his work in "France, England, Milan or in the Netherlands" as support for the view that he had travelled to Milan since he is known to have travelled to the other three places named.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 68. Holbein worked from prints, but Bätschmann & Griener argue that Hertenstein, who presumably requested these copies, might have sent the artist to Italy to view the originals himself.

- Müller, et al., 11, 47; Wilson, 69–70. Wilson cautions against too readily accepting that Ambrosius died, since other explanations for his disappearance from the record are possible. However, only Hans Holbein claimed their father's estate when he died in 1524.

- Müller, Christian (2006), pp.194–195

- Die Malerfamilie in Basel (in German). Basel. 1960. p. 210.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wilson, 70.

- North, 17. Lutheran Protestantism was introduced in Basel in 1522. After 1529, the ideas of Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) became widely accepted there, through the preaching of Johannes Oecolampadius (1482–1531).

- For example: Design for façade painting for the House of the Dance

- Rowlands, 53–54; Bätschmann & Griener, 64. See: Samuel Cursing Saul, and The Humiliation of Emperor Valentinian by Shapur, King of Persia (designs for the Council Chamber murals), and Rehoboam, a fragment of the Council Chamber murals.

- For example: Stained Glass Window Designs for the Passion of Christ.

- Dance of Death woodcuts.

- Stein, Wilhelm (1920), p.108

- Six of the Icones woodcuts.

- Strong,3; Wilson, 114–15; Müller, et al, 442–45. Title Sheet of Adam Petri's Reprint of Luther's Translation of the New Testament.

- tein, Wilhelm (1920), pp.108–110

- Bätschmann & Griener, 63.

- Ganz, 9.

- Ganz, 9. He later added the portrait of Meyer's first wife, after he returned from his first visit to London, by which time the demand for devotional art had largely dried up.

- Strong, 3; Rowlands, 56–59. Many copies of Holbein's portraits of Erasmus exist, but it is not always certain whether they were produced by the artist or by his studio.

- Bätschmann and Griener, 11; Müller, et al., 12, 16, 48–49, 66.

- "For a generation or more popular and establishment piety had led to the adornment and embellishment of churches, chapels, and cathedrals. Now there were different religious priorities and the overswelled ranks of the artists' guilds were feeling the pinch." Wilson, 116.

- Letter to Pieter Gillis (Petrus Aegidius), August 1526. Quoted by Wilson, 120. An angel was an English coin.

- Holbein, Zeichnungen vom Hofe Heinrichs VIII. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers. 1988. p. 9. ISBN 0-384-23843-2.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 158.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 160. Letter of 18 December 1526.

- Strong, 4; Wilson, 157–58. Strong suggests, with others, that More sent the sketch, which is now in Basel, to Erasmus as a gift; Wilson casts doubt on this, deducing from remarks by Erasmus that the gift was a finished version of the group portrait, since lost.

- Beyer, 68.

- For example: Portrait Study of John More and Portrait Study of Elizabeth Dauncey. "This group of drawings ranks among the supreme masterpieces of portraiture and surpasses in quality the more schematic and rapidly executed drawings of Holbein's later years." Waterhouse, 18.

- Portrait of William Warham, Archbishop of Canterbury.

- Strong, 4. Portrait of Nicholas Kratzer.

- Portrait of Sir Henry Guildford and Portrait of Mary, Lady Guildford.

- "Who was Holbein's Lady with a squirrel and a starling?""Gothic: art for England, 1400-1547, Victoria & Albert Museum"

- Wilson, 140; Foister, 30; King, 43–49. Anne Lovell's husband was Sir Francis Lovell, an esquire of the body to Henry VIII.

- Strong, 4; Claussen, 50.

- North, 21.

- Stein, Wilhelm (1929). Holbein der Jüngere (in German). Berlin: Julius Bard Verlag. p. 166.

- Strong, 4.

- Holbein, Zeichnungen vom Hofe Heinrichs VIII. p.11

- Bätschmann & Griener, 177.

- Rowlands, 76.

- Wilson, 156–57.

- Buck, 38–41; Bätschmann & Griener, 105–107; North, 25. The only known damage to a Holbein work was to The Last Supper, part of an altarpiece. The outer boards were lost during iconoclastic riots and the surviving section, on which only nine of the apostles can be seen, was later clumsily repaired.

- "Die Orgeln und Organisten im Basler Münster". basler-muensterkonzerte.ch. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- North, 24.

- Doctrinal issues concerning the communion were at the heart of Reformation theological controversy.

- Buck, 134.

- Wilson, 163; North, 23.

- Ganz, 7. See: Rehoboam, a fragment from a Council Chamber mural, and Samuel Cursing Saul, a design for a Council Chamber mural.

- Strong, 4; Buck, 6. According to a letter written by the Basel student Rudolf Gwalther to the Swiss reformer Heinrich Bullinger in 1538, Holbein "considered conditions in that realm to be happy".

- Rowlands, 81. Holbein was in England by September 1532, the date of a letter from the Basel authorities asking him to return.

- North, 26.

- Block Friedman & Mossler Figg, 417.

- Letter to Boniface Amerbach, quoted by Wilson, 178–79; Strong, 4.

- Wilson, 213.

- Wilson, 224–25; Foister, 120.

- Wilson, 184.

- Wilson, 183–86; Starkey, 496. According to historian David Starkey: "If the pageant as executed followed Holbein's surviving preparatory drawing at all faithfully, it was the most sophisticated piece of Renaissance theatrical design that London would see till the spectacular masque settings of Inigo Jones almost a century later".

- Buck, 98; North, 7. North suggests that the identification of the figure on the right as Dinteville's brother, the Bishop of Auxerre, was a mistake in an inventory of 1589; the bulk of scholarship follows M. F. S. Hervey (1900), who first identified the bishop as de Selve. See also Foister et al., 21–29.

- Buck, 103–104; Wilson, 193–97; Roskill, "Introduction", Roskill & Hand, 11–12. For a detailed online analysis of the painting's symbolism and iconography, see Mark Calderwood, "The Holbein Codes". Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 184.

- Parker, 53–54; Wilson, 209–10; Ives, 43. A drawing at Windsor inscribed "Anna Bollein Queen" has been discounted as incorrectly labelled by K. T. Parker and other scholars, citing heraldic sketches on the reverse. Anne's biographer Eric Ives believes that there is "little to reinstate" that drawing or another at the British Museum inscribed "Anne Bullen Regina Angliæ … decollata fuit Londini 19 May 1536", though he speculates that a 17th-century copy by John Hoskins "from an ancient original" may be based on a lost Holbein portrait of Anne. Derek Wilson, however, follows the recent scholarship of Starkey/Rowlands in arguing that the Windsor drawing is of Anne. He doubts that John Cheke was mistaken, who made the attribution in 1542 since Cheke knew many who had seen Anne.

- Rowlands, 88, 91.

- Wilson, 208–209.

- Strong, 5.

- Müller, et al., 13, 52; Buck, 112. The precise date is unknown of Holbein's appointment, but he was referred to in 1536 as the "king's painter" in a letter from French poet Nicholas Bourbon whom Holbein painted in 1535.

- Strong, 6; Rowlands, 96; Bätschmann & Griener, 189.

- Strong, 5. Strong calls it "arguably the most famous royal portrait of all time, encapsulating in this gargantuan image all the pretensions of a man who cast himself as 'the only Supreme Head in earth of the Church of England'."

- Buck, 115.

- Buck, 119; Strong, 6. This is the small portrait now in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid.

- Rowlands, 118, 224–26.

- Buck, 117.

- Buck, 120; Bätschmann & Griener, 189.

- Buck, 128–29; Wilson, 273–74; Rowlands, 118; Foister, 117. A preparatory drawing for this composition also survives, painted in by a later hand.

- Strong, 7; Waterhouse, 19.

- Wilson, 251. The likeness met with Henry's approval, but Christina declined the offer of marriage: "If I had two heads," she said, "I would happily put one at the disposal of the King of England".

- Auerbach, 49; Wilson, 250.

- Wilson, 250.

- Wilson, 251–52.

- Wilson, 252–53.

- Müller, et al., 13; Buck, 126.

- Wilson, 260.

- Starkey, 620.

- Strype, John, Ecclesiastical Memorials, vol 1 part 2, Oxford (1822), 456–457, "altered his outward countenance, to see the Lady so far unlike."

- Norton, Elizabeth (15 October 2009). Anne of Cleves: Henry VIII's Discarded Bride. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445606774.

- Schofield, 236–41; Scarisbrick, 484–85.

- Muhlbach, Luise (14 May 2010). Henry VIII and his Court. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 9781849891172.

- Warnicke, Retha M (13 April 2000). The Marrying of Anne of Cleves: Royal Protocol in Early Modern England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521770378.

- Wilson, 265; Schofield, 260–64. Cromwell's reluctance to arrange a divorce for Henry lay naked behind his fall, though the matter was not mentioned in the bill of attainder.

- Pollard, Alfred W (14 September 2004). Thomas Cranmer and the English Reformation, 1489-1556. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781592448654.

- Foister, 76–77. A clock salt was a complex instrument, including a clock, hourglass, sundial and compass.

- Wilson, 273, 276; North, 31. Holbein asked in his will for "Mr Anthony, the king's servant of Greenwich", to be repaid; scholars have usually presumed this to be Denny.

- Wilson, 267. Also, his uncle, the painter Sigmund Holbein, had died that autumn in Bern, leaving him substantial money and effects.

- Wilson, 245, 269; North, 31.

- North, 26; Wilson, 112–13.

- Claussen, 50. Claussen dismisses the theory as "pure nonsense".

- Wilson, 112–13.

- Müller, et al., 13; Wilson, 253, 268. Franz Schmid, Elsbeth's son by her first husband, travelled to Berne to take possession of Sigmund Holbein's estate in 1540. This implies that Hans Holbein's finances were still shared with his wife. Franz Schmid succeeded to the estate in Berne on 4 January 1541.

- Wilson, 253–54, 268, 278. Philipp and Jakob Holbein later became goldsmiths, the first moving to Augsburg, the second to London, where he died in 1552. The two daughters married merchants in Basel.

- Wilson, 277

- Claussen, 53.

- Wilson, 276.

- Wilson, 278.

- Wilson, 277; Foister, 168; Bätschmann and Griener, 10. From the location of his house, scholars deduce that Holbein was buried in either the church of St Katherine Cree or in that of St Andrew Undershaft.

- Ganz, 5–6.

- Müller, et al., 29–30.

- Wilson, 16; North, 12.

- Strong, 9.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 11.

- Buck, 41–43; Bätschmann and Griener, 135; Ganz, 4; Claussen, 50. Venus and Amor is sometimes considered a workshop portrait. Holbein also painted his own, very different, version of The Last Supper, based on Leonardo's The Last Supper in Milan.

- Strong, 9–10; North, 14; Sander, 17–18. The influence of Andrea del Sarto and Andrea Solari has also been detected in Holbein's work, as well as that of the Venetian Giovanni Bellini.

- Strong, 7, 10.

- Strong, 7, 10.

- Bätschmann and Griener, 134. His two drawings, done in France, of statues of Duc Jean de Berry (1340–1416) and his wife Jeanne de Boulogne (d. 1438) "suggest that Holbein learned the new technique in France".

- Strong, 8–10; Bätschmann and Griener, 134–35; Müller, et al., 30, 317. Bätschmann and Griener are not convinced that Holbein learned this directly from Clouet; they suggest he learned it from a mixture of French and Italian models. And Müller points out that, in any case, the technique was not unknown in Augsburg and Switzerland.

- Strong, 7; North, 30; Rowlands, 88–90. Karel van Mander wrote in the early 17th century that "Lucas" taught Holbein illumination, but John Rowlands downplays Horenbout's influence on Holbein's miniatures, which he believes follow the techniques of Jean Clouet and the French school.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 95.

- Buck, 32–33; Wilson, 88, 111; Ganz, 8; Bätschmann & Griener, 88–90. Holbein knew Grünewald's Lamentation and Burial of Christ at Issenheim, not far from Basel, where his father had worked in 1509 and between 1516 and 1517.

- Wilson, 96–103. The prints were not published until 1538, perhaps because they were thought too subversive at a time of peasants' revolts. The series was left incomplete by the death of the block cutter Hans Lützelburger in 1526, and was eventually published with 41 woodcuts by his heirs without mention of Holbein. The ten further designs were added in later editions.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 56–58, and Landau & Parshall, 216.

- 9 September, Francisco González Echeverría VI International Meeting for the History of Medicine, (S-11: Biographies in History of Medicine (I)), Barcelona. New Discoveries on the biography of Michael de Villeneuve (Michael Servetus) & New discoveries on the work of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus) VI Meeting of the International Society for the History of Medicine Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- 2011 "The love for truth. Life and work of Michael Servetus", (El amor a la verdad. Vida y obra de Miguel Servet.), printed by Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, collaboration with the Government of Navarre, Department of Institutional Relations and Education of the Government of Navarre, 607pp, 64 of them illustrations, p 215-228 & 62nd illustration (XLVII)

- 2000 "Find of new editions of Bibles and of two 'lost' grammatical works of Michael Servetus" and "The doctor Michael Servetus was descendant of jews", González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Abstracts, 37th International Congress on the History of Medicine, 10–15 September 2000, Galveston, Texas, U.S., pp. 22–23.

- 2001 "Portraits or graphical boards of the stories of the Old Gospel. Spanish Summary", González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Government of Navarra, Pamplona 2001. Double edition: facsimile (1543) and critical edition. Prologue by Julio Segura Moneo.

- Michael Servetus Research Archived 21 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine Website with a study on the three works by Servetus with woodcuts by Hans Holbein

- Bätschmann & Griener, 97.

- Wilson, 129; Foister, 127; Strong, 60; Rowlands, 130; Claussen, 49. Scholars are unsure of the exact date of Noli Me Tangere, usually given as between 1524 and 1526, or whether it was painted in England, Basel, or even France. The traditional view that Henry VIII owned the painting is discounted by Strong and Rowlands. Franny Moyle, however, writes, "The evidence that this was painted for [Thomas] More rests in part in the fact that by 1540 it was in Henry VIII's collection, and it is widely presumed that it was seized by the king at the point of More's attainder." The King's Painter, p. 157.

- Wilson, 129–30; Moyle, 158. Wilson contrasts Holbein's treatment with the earlier, freer, interpretation by Titian.

- Quoted by Wilson, 130.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 116; Wilson, 68.

- Strong, 5; Rowlands, 91.

- Foister, 140–41; Strong, 5.

- Rowlands, 92–93.

- North, 94–95; Bätschmann & Griener, 188.

- North, 25.

- Strong, 7.

- Strong, 8; Rowlands, 118–19.

- Buck, 16–17.

- Parker, 24–29; Foister, 103. Many of these studies have been coloured in or outlined in ink by later hands ("made worse by mending"), obstructing the analysis of Holbein's technique.

- Ganz, 11; Foister, 103. Foister, however, is doubtful, owing to "the inconsistency in the sizes of the drawn heads".

- Parker, 28; Rowlands, 118–20.

- Foister, 15.

- Ganz, 5.

- Strong, 5, 8; Foister, 15.

- North, 20.

- Strong, 6.

- Quoted by Michael, 237.

- Quoted by Michael, 239–40.

- Auerbach, 69–71.

- Wilson, 265.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 177–81.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 181.

- Rowlands, 118–20.

- Rowlands, 122.

- Auerbach, 69.

- Reynolds, 6–7.

- Strong, 7; Gaunt, 25.

- Reynolds, 7.

- Foister, 95; Rowlands, 113.

- North, 31.

- Michael, 240.

- North, 29; Waterhouse, 21.

- North, 29; Ackroyd, 191; Brooke, 9.

- North, 33.

- Waterhouse, 16–17.

- Müller, et al., 32–33.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 194.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 195.

- North, 33–34; Bätschmann & Griener, 146, 199–201. Among Van Mander's dubious anecdotes is the story that Holbein angrily threw a nobleman downstairs for pestering him.

- Wilson, 280–81; Gaunt, 27.

- Hearn, 46–47.

- Waterhouse, 13.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 194–95; Brooke, 52–56.

- Brooke, 53.

- Auerbach, 71.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 202. Philip Fruytiers depicted Howard and his family with Holbein's portraits of his ancestors Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, in the background.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 203.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 208.

- Bätschmann & Griener, 208–209; Borchert, 191. Borchert terms this process the "Romantic sacralization of the arts".

- Borchert, 187–88. The copy at Dresden was made by Bartholomäus Sarburgh in about 1637.

- Roskill, "Introduction", in Roskill & Hand, 9.

- Michael, 227.

References

- Ackroyd, Peter. The Life of Thomas More. London: Chatto & Windus, 1998. ISBN 1-85619-711-5.

- Auerbach, Erna. Tudor Artists: A Study of Painters in the Royal Service and of Portraiture on Illuminated Documents from the Accession of Henry VIII to the Death of Elizabeth I. London: Athlone Press, 1954. OCLC 1293216.

- Bätschmann, Oskar, and Griener, Pascal. Hans Holbein. London: Reaktion Books, 1997. ISBN 1-86189-040-0. Revised and expanded edition, London: Reaktion Books, 2014. ISBN 978-1-78023-171-6.

- Beyer, Andreas. "The London Interlude: 1526–1528." In Hans Holbein the Younger: The Basel Years, 1515–1532, Müller, et al., 66–71. Munich: Prestel, 2006. ISBN 3-7913-3580-4.

- Block Friedman, John; Mossler Figg, Kristen. Routledge Revivals: Trade, Travel and Exploration in the Middle Ages (2000): An Encyclopedia., 417. Taylor & Francis, 2017. ISBN 978-1-35166-132-4.

- Borchert, Till-Holger. "Hans Holbein and the Literary Art Criticism of the German Romantics." In Hans Holbein: Paintings, Prints, and Reception, edited by Mark Roskill & John Oliver Hand, 187–209. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2001. ISBN 0-300-09044-7.

- Brooke, Xanthe, and David Crombie. Henry VIII Revealed: Holbein's Portrait and its Legacy. London: Paul Holberton, 2003. ISBN 1-903470-09-9.

- Buck, Stephanie. Hans Holbein, Cologne: Könemann, 1999, ISBN 3-8290-2583-1.

- Calderwood, Mark. "The Holbein Codes: An Analysis of Hans Holbein's The Ambassadors ". Newcastle (Au): University of Newcastle, 2005. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- Claussen, Peter. "Holbein's Career between City and Court." In Hans Holbein the Younger: The Basel Years, 1515–1532, Müller, et al., 46–57. Munich: Prestel, 2006. ISBN 3-7913-3580-4.

- Foister, Susan. Holbein in England. London: Tate: 2006. ISBN 1-85437-645-4.

- Foister, Susan; Ashok Roy; Wyld, Martin. Holbein's Ambassadors: Making & Meaning. London: National Gallery Publications, 1997. ISBN 1-85709-173-6.

- Ganz, Paul. The Paintings of Hans Holbein: First Complete Edition. London: Phaidon, 1956. OCLC 2105129.

- Gaunt, William. Court Painting in England from Tudor to Victorian Times. London: Constable, 1980. ISBN 0-09-461870-4.

- Hearn, Karen. Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England, 1530–1630. London: Tate Publishing, 1995. ISBN 1-85437-157-6.

- Ives, Eric. The Life and Death of Anne Boleyn. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 978-1-4051-3463-7.

- King, David J. "Who was Holbein's lady with a squirrel and a starling?". Apollo 159, 507, May 2004: 165–75. Rpt. on bnet.com. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- Landau, David, and Parshall, Peter. The Renaissance Print: 1470-1550, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-300-05739-3.

- Michael, Erika. "The Legacy of Holbein's Gedankenreichtum." In Hans Holbein: Paintings, Prints, and Reception, edited by Mark Roskill & John Oliver Hand, 227–46. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2001. ISBN 0-300-09044-7.

- Müller, Christian; Stephan Kemperdick; Maryan W. Ainsworth; et al. Hans Holbein the Younger: The Basel Years, 1515–1532. Munich: Prestel, 2006. ISBN 3-7913-3580-4.

- North, John. The Ambassadors' Secret: Holbein and the World of the Renaissance. London: Phoenix, 2004. ISBN 1-84212-661-X.

- Parker, K. T. The Drawings of Hans Holbein at Windsor Castle. Oxford: Phaidon, 1945. OCLC 822974.

- Reynolds, Graham. English Portrait Miniatures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-521-33920-0.

- Roberts, Jane, Holbein and the Court of Henry VIII, National Gallery of Scotland, (1993). ISBN 0-903598-33-7.

- Roskill, Mark; Hand, John Oliver, eds. Hans Holbein: Paintings, Prints, and Reception. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 2001. ISBN 0-300-09044-7.

- Rowlands, John. Holbein: The Paintings of Hans Holbein the Younger. Boston: David R. Godine, 1985. ISBN 0-87923-578-0.

- Sander, Jochen. "The Artistic Development of Hans Holbein the Younger as Panel Painter during his Basel Years." In Hans Holbein the Younger: The Basel Years, 1515–1532, Müller, et al., 14–19. Munich: Prestel, 2006. ISBN 3-7913-3580-4.

- Scarisbrick, J. J. Henry VIII. London: Penguin, 1968. ISBN 0-14-021318-X.

- Schofield, John. The Rise & Fall of Thomas Cromwell: Henry VIII's Most Faithful Servant. Stroud (UK): The History Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7524-4604-2.

- Starkey, David. Six Wives: The Queens of Henry VIII. London: Vintage, 2004. ISBN 0-09-943724-4.

- Strong, Roy. Holbein: The Complete Paintings. London: Granada, 1980. ISBN 0-586-05144-9.

- Waterhouse, Ellis. Painting in Britain, 1530–1790. London: Penguin, 1978. ISBN 0-14-056101-3.

- Wilson, Derek. Hans Holbein: Portrait of an Unknown Man. London: Pimlico, Revised Edition, 2006. ISBN 978-1-84413-918-7.

- Zanchi, Mauro. "Holbein", Art e Dossier, Giunti, Firenze 2013. ISBN 9788809782501

- Zwingenberger, Jeanette. The Shadow of Death in the Work of Hans Holbein the Younger. London: Parkstone Press, 1999. ISBN 1-85995-492-8.

Further reading

- Crowe, Joseph Archer (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). pp. 578–580.

- Hervey, Mary F.S. Holbein's "Ambassadors": The Picture and the Men. An Historical Study. London: George Bell & Sons, 1900.

- Mantel, Hilary, and Salomon, Xavier F. Holbein's Sir Thomas More. New York: The Frick Collection, 2018.

- Moyle, Franny. The King's Painter: The Life and Times of Hans Holbein. London: Apollo (Head of Zeus), 2021; New York: Abrams Press, 2021.

- Nuechterlein, Jeanne. Hans Holbein: The Artist in a Changing World. London: Reaktion Books, 2020.

- O'Neill, J. The Renaissance in the North New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987.

- Reinhardt, Hans. Holbein: The Artist in a Changing World. Translated from the French by Prudence Montagu-Pollock. New York: French and European Publications, Inc., Paris: The Hyperion Press, 1938.

- Holbein and the Court of Henry VIII (no author named). London: The Queens Gallery, Buckingham Palace, 1978–1979 (exhibition catalogue).

External links

- Works by Hans Holbein at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Hans Holbein at Internet Archive

- A list of museums featuring the artist

- 2006 exhibition on Holbein in England at Tate Britain Archived 12 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Hans-Holbein.org 145 works by Hans Holbein the Younger

- Hans Holbein the Younger Gallery at MuseumSyndicate

- Michael Servetus Research Website with a graphical study on the three biblical works by Servetus with woodcuts of Hans Holbein, Icones.

- Fifteenth- to eighteenth-century European paintings: France, Central Europe, the Netherlands, Spain, and Great Britain, a collection catalog fully available online as a PDF, which contains material on Holbein the Younger (cat. no. 11)

- A documentary video about Holbein's finest painting, The Ambassadors.

- 116 artworks by or after Hans Holbein the Younger at the Art UK site

- Holbein: Capturing Character in the Renaissance, exhibition at The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, October 19, 2021–January 9, 2022.

- Holbein: Capturing Character, exhibition at The Morgan Library & Museum, New York City, February 11 through May 15, 2022.