Guðrøðr Óláfsson

Guðrøðr Óláfsson (died 10 November 1187) was a twelfth-century ruler of the kingdoms of Dublin and the Isles.[note 1] Guðrøðr was a son of Óláfr Guðrøðarson and Affraic, daughter of Fergus, Lord of Galloway. Throughout his career, Guðrøðr battled rival claimants to the throne, permanently losing about half of his realm to a rival dynasty in the process. Although dethroned for nearly a decade, Guðrøðr clawed his way back to regain control of a partitioned kingdom, and proceeded to project power into Ireland. Although originally opposed to the English invasion of Ireland, Guðrøðr adeptly recognised the English ascendancy in the Irish Sea region and aligned himself with the English. All later kings of the Crovan dynasty descended from Guðrøðr.

| Guðrøðr Óláfsson | |

|---|---|

| King of Dublin and the Isles | |

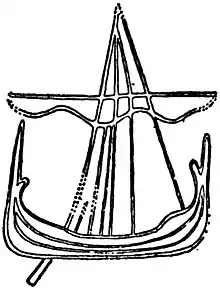

.jpg.webp) Guðrøðr's name as it appears on folio 46v of British Library Royal 13 B VIII (Expugnatio Hibernica): "Gottredum"[1] | |

| Reign | 1150s–1160 |

| Died | 10 November 1187 St Patrick's Isle |

| Burial | 1188 |

| Spouse | Findguala Nic Lochlainn |

| Issue |

|

| House | Crovan dynasty |

| Father | Óláfr Guðrøðarson |

| Mother | Affraic ingen Fergusa |

In the last year of his father's reign, Guðrøðr was absent at the court of Ingi Haraldsson, King of Norway, forging closer ties with the Kingdom of Norway. When Óláfr was assassinated by rival members of the Crovan dynasty in 1153, Guðrøðr returned to the Isles, overthrew his usurping cousins, and seized the throne for himself. Guðrøðr evidently pursued a more aggressive policy than his father, and the following year appears to have lent military assistance to Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, King of Cenél nEógain in the latter's bid for the high-kingship of Ireland. Not long afterwards, Guðrøðr faced a dynastic challenge from his brother-in-law, Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, Lord of Argyll, whose son, as a grandson of Óláfr, possessed a claim to the throne. Late in 1156, Guðrøðr and Somairle fought an inconclusive sea-battle and partitioned the kingdom of the Isles between them. Two years later Somairle struck again and forced Guðrøðr from the Isles altogether.

Guðrøðr appears to have spent his exile in the kingdoms of England and Scotland before journeying to Norway. In about 1161, Guðrøðr distinguished himself in the ongoing Norwegian civil wars at the final downfall of Ingi. Guðrøðr made his return to the Isles in 1164, in the aftermath of Somairle's defeat and death at the hands of the Scots. Although he regained the kingship itself, the territories ceded to Somairle in 1156 were retained by the latter's descendants. At some point in his career, Guðrøðr briefly held the kingship of Dublin. Although he was initially successful in fending off Muirchertach, the Dubliners eventually settled with the latter, and Guðrøðr returned to the Isles. This episode may have bearing on Guðrøðr's marriage to Findguala ingen Néill, Muirchertach's granddaughter. In 1170, Dublin fell to an Anglo-Irish alliance. The following year the ousted King of Dublin attempted to retake the town, and Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht attempted to dislodge the English from Dublin. In both cases, Guðrøðr appears to have provided military assistance against the English. In succeeding years, however, Guðrøðr aligned himself with one of the most powerful English conquerors, John de Courcy. Guðrøðr's assistance to John, who had married Guðrøðr's daughter, Affrica, may have played a critical role in John's successful conquest of the Kingdom of Ulaid. Guðrøðr died in 1187 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Rǫgnvaldr. Although Guðrøðr may have attempted to avert any succession disputes between his descendants, Rǫgnvaldr and his younger brother, Óláfr svarti, eventually fought each other over the throne, and the resulting conflict carried on into later generations.

Background

.png.webp)

Guðrøðr was a son of Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles[29] and his wife Affraic ingen Fergusa.[30] The men were members of the Crovan dynasty, a Norse-Gaelic kindred descended from Guðrøðr Crovan, King of Dublin and the Isles.[31] Following Guðrøðr Crovan's death in 1095, there is a period of uncertainty in the history of the Kingdom of the Isles. Although the latter's eldest son, Lǫgmaðr, appears to have succeeded to the kingship, he was soon forced to contend with factions supporting his younger brothers: Haraldr, and Óláfr. Although he successfully dealt with Haraldr, foreign powers from Ireland intruded into the Isles, and Magnús Óláfsson, King of Norway seized control of the kingdom. At some point, Óláfr was entrusted to the protection of Henry I, King of England, and spent his youth in England before his eventual restoration as King of the Isles in the second decade of the twelfth century.

The thirteenth- to fourteenth-century Chronicle of Mann reveals that Guðrøðr's mother, Affraic, was a daughter of Fergus, Lord of Galloway.[32] Several contemporary sources concerning Fergus' descendants suggest that he was married to an illegitimate daughter of Henry I, and that this woman was the mother of at least some of his offspring, including Affraic herself.[33][note 2] Although the union between Guðrøðr's parents is not dated in contemporary sources,[36] it appears to have been arranged in the 1130s or 1140s. The marital alliance forged between Óláfr and Fergus gave the Crovan dynasty valuable familial-connections with the English Crown, one of the most powerful monarchies in western Europe.[37] As for Fergus, the union bound Galloway more tightly to a neighbouring kingdom from which an invasion had been launched during the overlordsship of Magnús.[38] The alliance with Óláfr also ensured Fergus the protection of one of Britain's most formidable fleets, and further gave him a valuable ally outside the orbit of the Scottish Crown.[39]

Another alliance involving Óláfr was that with Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, Lord of Argyll. Perhaps at about 1140, during a period when the latter was allied with David I, King of Scotland, Somairle married Ragnhildr, Óláfr's daughter. There is reason to suspect that the alliance was an after effect of the Scottish Crown's advancing overlordship.[41] The marriage itself had severe repercussions on the later history of the Isles, as it gave the Meic Somairle—the descendants of Somairle and Ragnhildr—a claim to the kingship through Ragnhildr's royal descent.[42] In the words of the chronicle, the union was "the cause of the collapse of the entire Kingdom of the Isles".[43]

Early career

Although the Chronicle of Mann portrays Óláfr's reign as one of tranquillity,[49] a more accurate evaluation of his reign may be that he adeptly managed to navigate an uncertain political climate.[50] By the mid-part of the twelfth century, however, the ageing king's realm may well have begun to buckle under the strain,[51] as perhaps evidenced by the depredations wrought on the Scottish mainland by Óláfr's leading ecclesiast, Wimund, Bishop of the Isles.[52] Confirmation of Óláfr's concern over the royal succession may well be preserved by the Chronicle of Mann,[53] which states that Guðrøðr journeyed to the court of Ingi Haraldsson, King of Norway in 1152, where Guðrøðr rendered homage to the Norwegian king, and seemingly secured recognition of the royal inheritance of the Isles.[54] According to Robert's Chronica, the kings of the Isles owed the kings of Norway a tribute of ten gold marks upon the accession of a new Norwegian king. This statement could indicate that Guðrøðr rendered Ingi such a payment upon his visit to the Norwegian court in 1152.[55]

The following year marked a watershed in the history for the Kingdom of the Isles. For not only did David die late in May,[56] but Óláfr himself was assassinated about a month later, on 29 June, whilst Guðrøðr was still absent in Norway.[57] According to the chronicle, Óláfr had been confronted by three Dublin-based nephews—the Haraldssonar—the sons of his exiled brother, Haraldr. After hearing the demands of these men—that half of the kingdom should be handed over to them—a formal council was convened in which one of the Haraldssonar slew Óláfr himself. In the resulting aftermath, the chronicle relates that the Haraldssonar partitioned the island amongst themselves.[58] Whether the men attained any form of authority in the rest of the Isles is unknown.[59][note 3] Once in control, the chronicle reveals that the men fortified themselves against forces loyal to Guðrøðr, the kingdom's legitimate heir, by launching a preemptive strike against his maternal grandfather, Fergus. Although the invasion of Galloway was repulsed with heavy casualties, once the Haraldssonar returned to Mann the chronicle records that they slaughtered and expelled all resident Gallovidians that they could find.[62] This ruthless reaction evidently reveals an attempt to uproot local factions adhering to Guðrøðr and his mother.[63] Within months of his father's assassination, Guðrøðr executed his vengeance. According to the chronicle, he journeyed from Norway to Orkney, strengthened by Norwegian military support, and was unanimously acclaimed as king by the leading Islesmen. He is then stated to have continued on to Mann where he overcame his three kin-slaying cousins, putting one to death whilst blinding the other two, and successfully secured the kingship for himself.[64] Whether Guðrøðr succeeded to the throne in 1153[65] or 1154 is uncertain.[66] The chronicle itself states that he overcame the Haraldssonar in the autumn following their coup.[64]

Guðrøðr's reliance upon Norwegian assistance, instead of support from his maternal-grandfather, could suggest that the attack upon Galloway was more successful than the compiler of the chronicle cared to admit.[63] Additionally, the account of incessant inter-dynastic strife amongst the ruling family of Galloway, as recorded by the twelfth-century Vita Ailredi, suggests that Fergus may have struggled to maintain control of his lordship by the mid 1150s, and may also explain his failure to come to Guðrøðr's aid following Óláfr's death.[67] Óláfr and Guðrøðr's turn to Ingi occurred at about the same time that Norwegian encroachment superseded roughly thirty years of Scottish influence in Orkney and Caithness,[68] and could be evidence of a perceived wane in Scottish royal authority in the first years of the 1150s. In November 1153, following the death of David, Somairle seized the initiative and rose in revolt against the recently inaugurated Malcolm IV, King of Scotland. The dynastic-challenges faced by Malcolm, and the ebb of Scottish influence in the Isles, may partly account for Guðrøðr's success in consolidating control of the kingdom, and may be perceptible in the seemingly more aggressive policy he pursued as king in comparison to his father.[69]

Contested kingship

Midway through the twelfth-century, Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn, King of Cenél nEógain pressed forth to claim to the high-kingship of Ireland, an office then held by the elderly Toirrdelbach Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht.[79] In 1154, the forces of Toirrdelbach and Muirchertach met in a major conflict fought off the Inishowen coast, in what was perhaps one of the greatest naval battles of the twelfth century.[80] According to the seventeenth-century Annals of the Four Masters, Muirchertach's maritime forces were mercenaries drawn from Galloway, Arran, Kintyre, Mann, and "the territories of Scotland".[81] This record appears to be evidence that Guðrøðr, Fergus, and perhaps Somairle, provided ships to Muirchertach's cause.[82][note 5] Although Toirrdelbach's forces obtained a narrow victory, his northern maritime power seems to have been virtually nullified by the severity of the contest,[84] and Muirchertach soon after marched on Dublin,[85] gained overlordship over the Dubliners, and effectively secured himself the high-kingship of Ireland for himself.[86]

.jpg.webp)

The defeat of forces drawn from the Isles, and Muirchertach's subsequent spread of power into Dublin, may have had severe repercussions concerning Guðrøðr's career.[88] In 1155 or 1156, the Chronicle of Mann reveals that Somairle conducted a coup against Guðrøðr, specifying that Þorfinnr Óttarsson, one of the leading men of the Isles, produced Somairle's son, Dubgall, as a replacement to Guðrøðr's rule.[89] Somairle's stratagem does not appear to have received unanimous support, however, as the chronicle specifies that the leading Islesmen were made to render pledges and surrender hostages unto him, and that one such chieftain alerted Guðrøðr of Somairle's treachery.[90]

Late in 1156, on the night of 5/6 January, Somairle and Guðrøðr finally clashed in a bloody but inconclusive sea-battle. According to the chronicle, Somairle's fleet numbered eighty ships, and when the fighting concluded, the feuding brothers-in-law divided the Kingdom of the Isles between themselves.[92][note 6] Although the precise partitioning is unrecorded and uncertain, the allotment of lands seemingly held by Somairle's descendants in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries could be evidence that he and his son gained the southernmost islands of the Hebrides, whilst Guðrøðr retained the northernmost.[95] Two years later the chronicle reveals that Somairle, with a fleet of fifty-three ships, attacked Mann and drove Guðrøðr from the kingship into exile.[96] According to the thirteenth-century Orkneyinga saga, the contemporary Orcadian warlord Sveinn Ásleifarson had connections in the Isles, and overcame Somairle in battle at some point in the twelfth century. Although this source's account of Sveinn and Somairle is clearly somewhat garbled, it could be evidence that Sveinn aided Guðrøðr in his struggle against Somairle.[97] With Guðrøðr gone, it appears that either Dubgall or Somairle became King of the Isles.[98] Although the young Dubgall may well have been the nominal monarch, the chronicle makes it clear that it was Somairle who possessed the real power.[99] Certainly, Irish sources regarded Somairle as king by the end of his career.[98] The reason why the Islesmen specifically sought Dubgall as their ruler instead of Somairle is unknown. Evidently, Somairle was somehow an unacceptable candidate,[100] and it is possible that Ragnhildr's royal ancestry lent credibility to Dubgall that Somairle lacked himself.[101]

Exile from the Isles

Contemporaneous sources reveal that, upon his expulsion, Guðrøðr attempted to garner royal support in England and Scotland. For example, the English Pipe rolls record that, in 1158, the sheriffs of Worcester and Gloucester received allowances for payments made to Guðrøðr for arms and equipment.[103] Guðrøðr may have arrived in England by way of Wales. The English Crown's recent use of naval forces off the Gwynedd coast, as well as Guðrøðr's own familial links with the king himself, may account for the Guðrøðr's attempts to secure English assistance.[104] In any case, Guðrøðr was unable to gain Henry II's help, and the latter proceeded to busy himself in Normandy.[105] Guðrøðr next appears on record in Scotland, the following year, when he witnessed a charter of Malcolm to Kelso Abbey.[106] The fact that the Scottish Crown had faced opposition from Somairle in 1153 could suggest that Malcolm was sympathetic to Guðrøðr's plight.[107] Although the latter was certainly honourably treated by the Scots, as revealed by his prominent place amongst the charter's other witnesses, he was evidently unable to secure military support against Somairle.[108]

It is uncertain why Guðrøðr did not turn to his grandfather, Fergus, for aid. One possibility is that the defeat of the Gallovidian fleet in 1154 severely weakened the latter's position in Galloway. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that Galloway endured a bitter power struggle later that decade.[108][note 7] According to the twelfth- to thirteenth-century Chronicle of Holyrood, Malcolm overcame certain "confederate enemies" in Galloway in 1160.[111] Although the exact identities of these opponents are unknown, it is possible that this source documents a Scottish victory over an alliance between Somairle and Fergus.[112] Before the end of the year, Fergus retired to Holyrood Abbey,[113] and Somairle came into the king's peace.[114] Although the concordat between the Scottish Crown and Somairle may have taken place after the Malcolm's subjugation of Somairle and Fergus, an alternate possibility is that the agreement was concluded in the context of Somairle having aided the Scots in their overthrow of Fergus.[115] Somairle's deal with Scottish Crown may also have been undertaken not only in an effort to ensure that his own authority in the Isles was recognised by Malcolm, but to limit any chance of Guðrøðr receiving future royal support from the Scots.[116]

.jpg.webp)

Having failed to secure substantial support in England and Scotland, Guðrøðr appears to have turned to Ingi, his nominal Norwegian overlord.[118] In late 1160 or early 1161, Guðrøðr distinguished himself in the ongoing civil war in the Norwegian realm, as evidenced by Hákonar saga herðibreiðs within the thirteenth-century saga-compilation Heimskringla.[119] The fact that the Icelandic annals allege that Guðrøðr assumed the kingship of the Isles in 1160 could be evidence that, whilst in Norway, Ingi formally recognised Guðrøðr as king in a public ceremony.[120] There is reason to suspect that Guðrøðr's support of Ingi may have been undertaken in the context of fulfilling military obligations as a vassal.[121] Be that as it may, Hákonar saga herðibreiðs reveals that Guðrøðr played an important part in Ingi's final downfall in battle at Oslo in 1161.[119] Up until 1155, Ingi had shared the kingship with his brothers Sigurðr and Eysteinn. With both of these brothers dead by 1157, Ingi was forced to contend with Hákon Sigurðarson, who had been elected to the kingship within the year.[122] In regard to Guðrøðr himself, the saga relates that during this final battle against Hákon, Guðrøðr, at the head of one thousand, five hundred men, went over to Hákon's side. Guðrøðr's decision to abandon his embattled overlord tipped the scales in favour of Hákon, and directly contributed to Ingi's defeat and death.[119] The young Magnús Erlingsson was elected king after Ingi's death, and following the fall of Hákon,[123] was crowned king in 1163/1164.[124] It is likely that Guðrøðr was present at Magnús Erlingsson's coronation,[121] and possible that Guðrøðr rendered homage to him as well.[125]

Return to the Isles

Somairle was slain in an unsuccessful invasion of mainland Scotland in 1164.[131] The declaration in the fifteenth- to sixteenth-century Annals of Ulster, of Somairle's forces being drawn from Argyll, Kintyre, Dublin, and the Isles, reveals the climax of Somairle's authority and further confirms his usurpation of power from Guðrøðr.[132] Despite the record preserved by the Icelandic annals—that Guðrøðr regained the kingship of the Isles in 1160—it appears that Guðrøðr made his actual return to the region after Somairle's fall.[133] Although it is possible that Dubgall was able to secure power following his father's demise,[134] it is evident from the Chronicle of Mann that the kingship was seized by Guðrøðr's brother, Rǫgnvaldr, before the end of the year.[135] Almost immediately afterwards, Guðrøðr is said by the same source to have arrived on Mann, ruthlessly overpowered his brother, having him mutilated and blinded.[136] Guðrøðr thereafter regained the kingship,[137] and the realm was divided between the Crovan dynasty and the Meic Somairle,[138] in a partitioning that stemmed from Somairle's strike against Guðrøðr in 1156.[139][note 8]

In an entry dated 1172, the chronicle states that Mann was invaded by a certain Ragnall mac Echmarcacha, a man who slaughtered a force of Manx coast-watchers before being slain himself in a later engagement on the island. Although the chronicle claims that Ragnall was of "royal stock",[149] his identity is otherwise uncertain. One possibility is that this man's final adventure was somehow related to the dramatic fall of Norse-Gaelic Dublin in the preceding years.[150] He could have possessed a connection with the former rulers of the town, as a distant relative of Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin and the Isles.[151] Alternately, Ragnall's name could indicate that he was a member of the Meic Torcaill, a family that possessed royal power in Dublin as late as the English conquest, and evidently possessed some lands afterwards.[152][note 10]

Another possibility is that Ragnall's attack was somehow related to events in northern Ireland, where the Meic Lochlainn lost hold of the Cenél nEógan kingship to Áed Méith Ua Néill. In fact, it is possible that the invader himself was a member of the Uí Catháin, a branch of the Uí Néill who were opponents of John de Courcy, Guðrøðr's English ally and son-in-law.[155] Although the chronicle specifically dates Ragnall's invasion to 1172, the chronological placement of the passage positions it between events dating to 1176 and 1183.[156] This could indicate that the incursion took place in the immediate aftermath of John's conquest of Ulaid in 1177. Therefore, it is conceivable that Ragnall embarked upon his invasion whilst Guðrøðr was absent from Mann assisting John in Ireland.[152]

King of Dublin

For a brief duration of his career, Guðrøðr appears to have possessed the kingship of Dublin. The chronology of his rule is unclear, however, as surviving sources concerning this episode are somewhat contradictory.[157] According to the Chronicle of Mann, the Dubliners invited Guðrøðr to rule over them as king in the third year of his reign in the Isles.[158] If correct, such an arrangement would have almost certainly provoked Muirchertach, the Dubliners' Irish overlord.[159][note 11] In fact, the chronicle reveals that Muirchertach indeed took exception to such overtures, and marched on Dublin with a massive host before forming up at "Cortcelis". Whilst in control of Dublin, Guðrøðr and the defending Dubliners are stated to have repulsed a force of three thousand horsemen under the command of a certain Osiblen. After the latter's fall, Muirchertach and his remaining host retired from the region.[158]

The chronicle's version of events appears to be corroborated by the Annals of Ulster. Unlike the previous source, however, this one dates the episode to 1162. Specifically, Muirchertach's forces are recorded to have devastated the Ostman lands of "Magh Fitharta" before his host of horsemen were repulsed.[161] Despite the difference in their chronologies, both accounts refer to similar military campaigns, and the uncertain place names of "Cortcelis" and "Magh Fitharta" may well refer to nearby locations roughly in the Boyne Valley.[162] Another source documenting the conflict is the Annals of the Four Masters. According this account preserved by this source, after Muirchertach's setback at Dublin and subsequent withdrawal in 1162, he left the forces of Leinster and Mide to campaign against the Dubliners. In time, the source states that a peace was concluded between the Irish and the Dubliners in which the latter rendered a tribute of one hundred forty ounces of gold to Muirchertach.[163] According to the Annals of Ulster, this peace was reached after Diarmait Mac Murchada, King of Leinster plundered Dublin and gained dominance over the inhabitants.[164] The payment reveals that the Dubliners recognised Diarmait's overlord, Muirchertach, as their own overlord, which in turn suggests that the price for peace was Guðrøðr's removal from the kingship.[165]

In the winter of 1176/1177, the chronicle reveals that Guðrøðr was formally married to Muirchertach's granddaughter, Findguala Nic Lochlainn, in a ceremony conducted under the auspices of the visiting papal legate, Vivian, Cardinal priest of St Stephen in Celio Monte.[167][note 12] The precise date when Guðrøðr and Findguala commenced their liaison is unknown,[170] and the two could have been a couple for some time before their formal marriage.[171] It is possible that the union was originally brokered as a compromise on Muirchertach's part, as a means to placate Guðrøðr for withdrawing from Dublin.[172] The demonstrable unreliability of the chronicle's chronology, and the apparent corroboration of events by the Annals of the Four Masters and the Annals of Ulster, suggests that the Guðrøðr's adventure in Dublin date to about 1162.[157] Such a date, however, appears to contradict the fact that Guðrøðr seems to have endured Norwegian exile in 1160/1161, and apparently only returned to the Isles in 1164.[173] If the chronicle's date is indeed correct, Guðrøðr's inability to incorporate Dublin into the Kingdom of the Isles could well have contributed to his loss of status to Somairle.[174]

There may be reason to suspect that Guðrøðr's defeat to Somairle was partly enabled by an alliance between Muirchertach and Somairle.[175] For example, Argyllmen formed part of the mercenary fleet utilised by Muirchertach in 1154,[176] and it is possible that the commander of the fleet, a certain Mac Scelling, was a relation of Somairle himself. If Muirchertach and Somairle were indeed allied at this point in time it may have meant that Guðrøðr faced a united front of opposition.[177] If correct, it could also be possible that Þorfinnr participated in Somairle's insurrection as an agent of Muirchertach.[178] On the other hand, the fact that Somairle and Muirchertach jostled over ecclesiastical affairs in the 1160s suggests that these two were in fact rivals.[179] Furthermore, the fact that Þorfinnr may have been related to a previous King of Dublin could reveal that Þorfinnr himself was opposed to Muirchertach's foreign overlordship.[104] If Guðrøðr's difficulties in Dublin indeed date to a period just before Somairle's coup, the cooperation of men like Þorfinnr could be evidence that Dubgall—on account of his mother's ancestry and his father's power—was advanced as a royal candidate in an effort to counter Muirchertach's overlordship of Dublin.[179][note 13]

Opposed to the English in Ireland

.png.webp)

Later in his reign, Guðrøðr again involved himself in the affairs of Dublin.[185] In 1166, the slaying of Muirchertach meant that two men made bids for the high-kingship of Ireland: Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair, King of Connacht and Diarmait.[186] The latter had possessed the overlordship of Dublin since Muirchertach's actions there in 1162.[187] Within the same year as Muirchertach's fall, however, Diarmait was overcome by Ruaidrí and his allies, and forced him from Ireland altogether. Although Ruaidrí thereupon gained the high-kingship for himself, Diarmait made his return the following year enstrengthened with English mercenaries, and reclaimed the core of his lands.[188] In 1170 even more English troops flocked to Diarmait's cause, including Richard de Clare, Earl of Pembroke, who successfully stormed the Norse-Gaelic enclave of Waterford.[189] Richard soon after married Diarmait's daughter, Aífe, and effectively became heir to kingship of Leinster and the overlordship of Dublin.[190] Later that year, the combined forces of Diarmait and Richard marched on Dublin, and drove out the reigning Ascall mac Ragnaill, King of Dublin.[191]

According to the twelfth-century Expugnatio Hibernica, Ascall and many of the Dubliners managed to escape by fleeing to the "northern islands".[193] On one hand, this term could well refer to Orkney.[194][note 14] On the other hand, it is also possible that the term refers to the Hebrides or Mann.[196] If so, this source would appear to be evidence that the Dubliners had retained close links with the Isles.[197] Whatever the case, within weeks of Diarmait's death early in May 1171, Ascall made his return to Dublin.[198] The account of events recorded by Expugnatio Hibernica and the twelfth- to thirteenth-century La Geste des Engleis en Yrlande indicate that Ascall's forces consisted of heavily armoured Islesmen and Norwegians.[199] The invasion itself was an utter failure, however, and Ascall himself was captured and executed.[200] Amongst the slain appears to have been Sveinn himself.[201]

The successive deaths of Diarmait and Ascall left a power vacuum in Dublin that others sought to fill. Almost immediately after Ascall's fall, for example, Ruaidrí had the English-controlled town besieged.[202] Expugnatio Hibernica records that he and Lorcán Ua Tuathail, Archbishop of Dublin sent for Guðrøðr, and others in the Isles, asking them to blockade Dublin by sea.[203][note 15] Whilst it is possible that Guðrøðr may have been enticed to assist the Irish through the promise of financial compensation, and perhaps the possession of any vessel his fleet captured in the operation, there is reason to suspect that the Islesmen were disquieted by prospect of permanent English authority in the region.[205] Certainly, Expugnatio Hibernica states that "the threat of English domination, inspired by the successes of the English, made the men of the Isles act all the more quickly, and with the wind in the north-west they immediately sailed about thirty ships full of warriors into the harbour of the Liffey".[203] Although the operation was one of the greatest military mobilisations that the Irish mustered in the twelfth century,[205] the blockade was ultimately a failure, and Dublin remained firmly in the hands of the English.[206] Ascall was the last Norse-Gaelic King of Dublin;[207] and before the end of the year, Clare relinquished possession of Dublin to his own liege lord, Henry II, King of England, who converted it into an English royal town.[208]

Aligned with the English in Ireland

According to the Chronicle of Northampton, Guðrøðr attended the coronation of Henry II's teenage son, Henry, in 1170.[209] The participation of monarchs such as Guðrøðr and William I, King of Scotland in the ceremony partly illustrates the imperial aspect of the Plantagenet authority in the British Isles.[210] Guðrøðr's close relations with the English Crown may have revolved around ensuring royal protection from the English invaders of Ireland–especially considering his former control of Dublin.[211] With the defeat of the Dubliners at the hands of English adventurers, and the ongoing entrenchment of the English throughout Ireland itself, the Crovan dynasty found itself surrounded by a threatening, rising new power in the Irish Sea zone.[212] Despite his original opposition to the English in Dublin, Guðrøðr did not take long to realign himself with this new power,[213] as exemplified through the marital alliance between his daughter, Affrica, and one of the most powerful incoming Englishmen, John de Courcy.[214]

In 1177, John led an invasion of Ulaid (an area roughly encompassing what is today County Antrim and County Down). He reached Down (modern day Downpatrick), drove off Ruaidrí Mac Duinn Sléibe, King of Ulaid, consolidated his conquest, and ruled with a certain amount of independence for about a quarter of a century.[215] Although the precise date of the marriage between John and Affrica is unknown,[216] the union itself may well have attributed to his stunning successes in Ireland.[217][note 16] Certainly, decades later in the reign of Guðrøðr's son and successor, Rǫgnvaldr, John received significant military support from the Crovan dynasty,[220] and it is not improbable that Guðrøðr himself supplied similar assistance.[221] In the 1190s, John also received military assistance from Guðrøðr's kinsman Donnchad mac Gilla Brigte, Earl of Carrick. Like Guðrøðr, Donnchad was a grandson of Fergus,[222] and it possible that John's marriage to Affrica accounts for Donnchad's cooperation with him.[223]

.jpg.webp)

Although the promise of maritime military support could well have motivated John to align himself with Guðrøðr,[225] there may have been a more significant aspect to their alliance.[226] The rulers of Ulaid and those of Mann had a bitter past-history between them, and it is possible that the binding of John to the Crovan dynasty was actually the catalyst of his assault upon the Ulaid. In fact, Guðrøðr formalised his own marriage to Findguala in 1176/1177, and it was by this union that Guðrøðr bound his own dynasty with the Meic Lochlainn, another traditional foe of the Ulaid.[227] Another contributing factor to the alliance between Guðrøðr and John may have been the Meic Lochlainn's loss of the Cenél nEógain kingship to the rival Uí Néill dynast Áed Méith in 1177.[155] The latter certainly clashed with John before the end of the century, and the strife between the Uí Néill and Meic Lochlainn continued on for decades.[228] In any case, the unions meant that John was protected on his right flank by Guðrøðr, through whom John shared a common interest with the Meic Lochlainn, situated on his left flank.[229] John would have almost certainly attempted to use such alignments to his advantage,[227] whilst Guðrøðr may have used John's campaigning against the Ulaid as a means of settling old scores.[230] The marriage alliance between Guðrøðr and John partly exemplifies the effect that the English conquest of Ireland had upon not only Irish politics but that of the Isles as well.[231]

Ecclesiastical activities

.jpg.webp)

There is reason to regard Óláfr, like his Scottish counterpart David, as a reforming monarch.[233] Guðrøðr continued Óláfr's modernising policies, as evidenced by surviving sources documenting the ecclesiastical history of the Isles.[234] For example, Guðrøðr confirmed his father's charter to the abbey of St Mary of Furness, in which the monks of this Cistercian house were granted the right to select the Bishop of the Isles.[235] Guðrøðr granted the English priory of St Bees the lands of "Escheddala" (Dhoon Glen) and "Asmundertoftes" (Ballellin) in exchange for the church of St Óláfr and the lands of "Euastad" (perhaps near Ballure).[236][note 17] In the reigns of Guðrøðr's succeeding sons, the Benedictine priory of St Bees continued to receive royal grants of Manx lands.[238] The Chronicle of Mann reveals that Guðrøðr gave lands at Myroscough to the Cistercian abbey of Rievaulx in England. The chronicle also notes that a monastery was constructed on these lands, and that the lands eventually passed into the possession of the abbey of St Mary of Rushen.[239] Guðrøðr also granted certain commercial rights and protections to the monks of the monastery of Holm Cultram, another Cistercian house in England.[240]

.jpg.webp)

The ecclesiastical jurisdiction within Guðrøðr's kingdom was the Diocese of the Isles. Little is known of its early history, although its origins may well lie with the Uí Ímair imperium.[243][note 19] Ecclesiastical interconnection between the Isles and Dublin seems to have been severed during a period of Irish overlordship of Dublin, at about the beginning of Guðrøðr Crovan's reign in the Isles.[247] Before the midpoint of the twelfth century, Óláfr firmly established the Diocese of the Isles to correspond to the territorial borders of his kingdom,[248] and seems to have initiated the transfer the ecclesiastical obedience of the Isles from the Archdiocese of Canterbury to Archdiocese of York. Such changes may have been orchestrated as a means to further distance his diocese from that of Dublin, where diocesan bishops were consecrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury.[249] In 1152, steps were undertaken by the papacy to elevate the Diocese of Dublin to an archdiocese. Dublin's political and economic ties with the Isles could have meant that the Bishop of the Isles was now in danger of becoming subordinate to the Archbishop of Dublin. For Óláfr, such an event would have threatened to undermine both his ecclesiastical authority and secular power within his own realm.[250] As a result of Óláfr's inability to have an ecclesiast of his own choice formally consecrated as bishop, and his own refusal to accept one favoured by the Archbishop of York, the episcopal see of the Isles appears to have been vacant at the same time of Dublin's ecclesiastical ascendancy. In consequence, without a consecrated bishop of its own, Óláfr's diocese seems to have been in jeopardy of falling under Dublin's increasing authority.[251] Moreover, in 1152, David I attempted to have the dioceses of Orkney and the Isles included within the prospective Scottish Archdiocese of St Andrews.[252]

.png.webp)

It may have been in the context of this ecclesiastical crisis in the Isles that Guðrøðr undertook his journey to Norway in 1152. Guðrøðr's overseas objective, therefore, may have been to secure the patronage of a Scandinavian metropolitan willing to protect the Diocese of the Isles.[254] Certainly, Guðrøðr's stay in Norway coincided with the Scandinavian visit of the papal legate Nicholas Breakspeare, Cardinal-Bishop of Albano,[255] a man who had been tasked to create Norwegian and Swedish ecclesiastical provinces in order to further extend the papacy's authority into the northern European periphery.[256][note 20] Eventually the newly created Norwegian province—the Archdiocese of Niðaróss—encompassed eleven dioceses in and outside mainland Norway. One such overseas diocese was that of the Isles,[262] officially incorporated within the province in November 1154.[263][note 21] Although Óláfr did not live long enough to witness the latter formality, it is evident that the remarkable overseas statecraft undertaken by Óláfr and Guðrøðr secured their kingdom's ecclesiastical and secular independence from nearby Dublin.[265] The establishment of the Norwegian archdiocese bound outlying Norse territories closer to Norwegian royal power.[266] In effect, the political reality of the Diocese of the Isles—its territorial borders and nominal subjection to far-off Norway—appears to have mirrored that of the Kingdom of the Isles.[267]

.jpg.webp)

Despite the ecclesiastical reorientation, the next Bishop of the Isles known from Manx sources was consecrated by Roger de Pont l'Evêque, Archbishop of York. This bishop, an Englishman named Gamaliel, may have been consecrated between October 1154 and early 1155, possibly before news of the diocesesan realignment reached the Isles.[269] Although it is possible that Gamaliel was consecrated without Guðrøðr's approval, the bishop appears to have witnessed at least one of the latter's charters.[270] The fact that Gamaliel was buried in Peterborough could suggest that he was removed from his see at some point.[271]

.jpg.webp)

The next known bishop was Reginald, a Norwegian who witnessed the bitter struggles between Guðrøðr and Somairle, and who seems to have died in about 1170.[272] It is possible that Reginald was consecrated in Norway in 1153/1154, and that the York-backed Gamaliel was compelled to resign the see to him.[273] Reginald is the first Bishop of the Isles to be attested by the Icelandic annals, which could indicate that he was the first such bishop to recognise the authority of Niðaróss.[274] Either Gamaliel or Reginald could have been the unnamed Bishop of the Isles who is stated by Robert's Chronica to have met with William and Henry II at Mont St Michel.[275] Robert's account of the meeting indicates that the kings of the Isles were obligated to render tribute to newly crowned kings of Norway.[276] It is possible that Reginald followed Guðrøðr into exile after the latter's defeat to Somairle.[277] Reginald's successor was Christian, an Argyllman who appears to have been appointed by Somairle or his sons.[278] The fact that Christian did not receive acknowledgement from the Archbishop of Niðaróss could be evidence that Reginald remained in Norway.[279] The apparent antipathy between Guðrøðr and Christian may be evidenced by the fact that it was Silvan, Abbot of Rievaulx—and not Christian—who conducted the marriage ceremony of Guðrøðr and Findguala during Vivian's visit in 1176/1177.[280]

Death and descendants

.jpg.webp)

According to the Chronicle of Mann, Guðrøðr had four children: Affrica, Rǫgnvaldr, Ívarr, and Óláfr svarti.[282] Although the chronicle specifically states that Findguala was Óláfr svarti's mother, and that he had been born before his parents' formalised marriage,[283] the mothers of the other three children are unknown or uncertain.[31] According to the anonymous praise-poem Baile suthach síth Emhna, Rǫgnvaldr's mother was Sadb, an otherwise unknown Irishwoman who may have been a wife or concubine of Guðrøðr.[284][note 22] As for Ívarr, nothing further is recorded of him,[285] although it is possible that his mother was also the product of an uncanonical liaison.[286] During the twelfth century, the Church sought to emphasise the sanctity of marriage, and took steps to combat concubinage.[287] As such, the record of Vivian's part in the marriage ceremony of Guðrøðr and Findguala may be evidence of an attempt by the papal representative to personally reinforce a stricter rule of marriage in the region.[288] In any case, there may be evidence to suggest that Guðrøðr had another son, Ruaidrí, who appears in a royal charter recorded as Rǫgnvaldr's brother ("Rotherico, fratre meo").[289] There is also reason to suspect that Guðrøðr had another daughter,[290] as the Chronicle of Mann describes a thirteenth century Bishop of the Isles, a man named Reginald, to have been of royal birth,[291] and to have been a sister-son of Óláfr svarti.[292]

Many anecdotes about him worthy of being remembered could be told, which for brevity's sake we have omitted.

— a less-than-illuminative excerpt from the Chronicle of Mann concerning Guðrøðr.[293]

Guðrøðr died on 10 November 1187 on St Patrick's Isle.[294] The fact that Guðrøðr and his son, Óláfr svarti, are recorded to have died on this islet could indicate that it was a royal residence.[295][note 23] In any case, the following year Guðrøðr was finally laid to rest on Iona,[130] an island upon which the oldest intact building is St Oran's Chapel.[298] Certain Irish influences in this building's architecture indicate that it dates to about the mid twelfth century.[299] The chapel could well have been erected by Óláfr or Guðrøðr.[129][note 24] Certainly, their family's remarkable ecclesiastical activities during this period suggest that patronage of Iona is probable.[300]

Upon Guðrøðr's death the chronicle claims that he left instructions for his younger son, Óláfr svarti, to succeed to the kingship since he had been born "in lawful wedlock".[301] On one hand, this record could be evidence that Guðrøðr continued to advance the institution of kingship in the Isles. For example, this episode appears to be the earliest record of a ruling member of the Crovan dynasty designating a royal successor. If so, such an arrangement may have been borne out of Guðrøðr's own bitter difficulties with rival claimants to the throne.[302] On the other hand, it is uncertain if the chronicle has preserved an accurate account of events,[303] as the Islesmen are stated to have chosen Rǫgnvaldr to rule instead, because unlike Óláfr svarti, who was only a child at the time, Rǫgnvaldr was a hardy young man fully capable to reign as king.[304] One possibility is that Guðrøðr may have intended for Rǫgnvaldr to temporarily rule as a lieutenant of sorts until Óláfr svarti was able to hold sway himself.[305] Although Rǫgnvaldr appears to have later forged an alliance with the Meic Somairle, and may have temporarily reunited the entire Kingdom of the Isles under his own leadership,[306] he was later opposed by Óláfr svarti, and the ensuing violent conflict between Guðrøðr's descendants carried on to further generations.[307]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Guðrøðr Óláfsson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Since the 1990s, academics have accorded Guðrøðr various personal names in English secondary sources: Godfrey,[2] Godhfhraidh,[3] Godred,[4] Goðrøðr,[5] Gofhraidh,[6] Gofraid,[7] Gofraidh,[8] Gothred,[9] Gottred,[10] Guthred,[11] Guðrøð,[12] Guðrǫðr,[13] Guðröðr,[14] Gudrød,[15] Gudrødr,[16] Guðrøðr,[17] and Guthfrith.[18] Likewise, academics have accorded Guðrøðr various patronyms in English secondary sources: Godfrey mac Aulay,[19] Godhfhraidh mac Amhlaoibh,[3] Godred Olafsson,[20] Godred Óláfsson,[21] Gofhraidh mac Amhlaíbh,[6] Gofraid Mac Amlaíb,[22] Gofraid mac Amlaíb,[23] Gofraidh mac Amhlaoibh,[24] Guðrøð Óláfsson,[12] Guðrǫðr Óláfsson,[13] Guðröðr Óláfsson,[25] Guðrøðr Óláfsson,[26] and Guðrøðr Ólafsson.[27] Guðrøðr has also been accorded an epithet: Godred the Black.[28]

- In specific regard to Guðrøðr, for example, the kinship between him and Henry I's maternal grandson, and eventual royal successor, Henry II, King of England, is noted by the twelfth-century Chronica of Robert de Torigni, Abbot of Mont Saint-Michel.[34] Henry II's mother was Matilda, daughter of Henry I.[35] The Chronica notes that Guðrøðr and Henry II were related by blood through Matilda, stating in Latin: "Est enim prædictus rex consanguineus regis Anglorum ex parte Matildis imperatricis matris suæ" ("For the aforesaid king is the cousin of the English king on the side of Matilda the empress, his mother").[34]

- According to the chronicle, Haraldr had been castrated by at some point in the late 1090s. If correct, it would seem that the Haraldssonar were at least in their fifties when they confronted their uncle,[60] a man who must have been at least in his late fifties.[61]

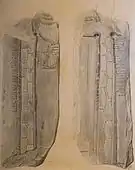

- The inscription of the vessel may date to about the time of the Crovan dynasty, possibly from about the eleventh- to the thirteenth century.[71] The vessel appears to be similar to those that appear on seals borne by members of the dynasty.[73] Members of the dynasty known to have borne seals include: Guðrøðr himself,[74] (Guðrøðr's son) Rǫgnvaldr,[75] and (Óláfr svarti's son) Haraldr.[76] Evidence of Guðrøðr's seal stems from his 1154 charter of confirmation to Furness, which states: "in order that this licence... may be firmly observed in my kingdom, I have strengthened it by the authority of my seal affixed to the present charter".[77] No seal used by a member of the dynasty survives today.[78]

- An alternate possibility is that the annal does not refer to Galloway at all, and that it actually refers to the Gall Gaidheil of Arran, Kintyre, Mann, and the territory of Scotland.[83]

- The chronicle dates the battle to the year 1156. Since the start of a new year in the Julian calendar is 25 March, the year of the battle in the Gregorian calendar is 1157.[93] Whatever the year, the weather conditions must have been particularly good to permit a naval battle at this time of season.[94]

- The next secular witness listed after Guðrøðr is Fergus' son, Uhtred. Whether the latter was there in defiance of his father—or as a representative of him—is unknown. It is possible that discussion regarding Guðrøðr's plight was one of the factors in Uhtred's attestation.[110]

- At one point, after noting this 1156 segmentation, the chronicle laments the "downfall" of the Kingdom of the Isles from the time Somairle's sons "took possession of it".[140] One possibility is that this statement is evidence that members of the Meic Somairle held a share of the kingdom before their father's demise.[141] It could even be evidence that it was not Somairle who had possessed the partition, but his sons.[142]

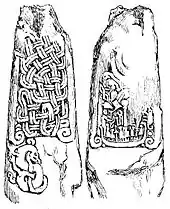

- The stone is carved in a Scandinavian style.[145] It is similar to other Manx[146] and Anglo-Scandinavian sculpted stones.[147] It may date to the tenth- or eleventh century.[148]

- Ascall was a member of the Meic Torcaill.[153] If Ragnall was indeed a member of this family, his name could indicate that he was a son of Echmarcach Mac Torcaill,[152] a man who—along with his brother Aralt—witnessed a charter of Diarmait between 1162 and 1166.[154]

- Following Muirchertach's defeat of Toirrdelbach in 1154, and the former's march on Dublin, the Annals of the Four Masters reports that the Dubliners rendered Muirchertach the kingship and gave him one thousand, two hundred cattle.[160]

- Findguala appears to have been a daughter of Niall Mac Lochlainn, King of Cenél nEógain.[168] The fact that the chronicle describes her as Muirchertach's granddaughter without mentioning her father could indicate that the union was envisioned as a bond with her grandfather and not her father.[169]

- There may be reason to suggest that Þorfinnr was distantly related to the Meic Somairle through Ragnhildr's ancestry. Specifically, it is possible that Ragnhildr's mother was Ingibjǫrg, daughter of Páll Hákonarson, Earl of Orkney. Ingibjǫrg was in turn a maternal granddaughter of Moddan, an eminent Caithnessman who had a son named Óttar. The fact that Moddan had a son so-named could be evidence that Moddan's wife was related to Þorfinnr's family (since Þorfinnr's father was a man named Óttar as well). If all these possibilities are correct, it is conceivable that a familial relationship such as this could have played a part in Þorfinnr's allegiance to Somairle.[180] There may have been another factor contributing to animosity between Þorfinnr and Guðrøðr.[181] For example, it is possible that Þorfinnr was related to Ottar mac meic Ottair, King of Dublin, an Islesmen who had attained the kingship of Dublin in 1142.[182] This act may well have represented a threat to the authority of Guðrøðr's father, and the prospects of Guðrøðr himself.[183] Certainly, the kin-slaying Haraldssonar who slew Óláfr a decade after Ottar's accession were raised in Dublin. Enmity between Þorfinnr and Guðrøðr, therefore, could have been a continuation of hostilities between their respective families.[181]

- Orkney is located in a chain of islands known as the Northern Isles. In Old Norse, these islands were known as Norðreyjar, as opposed to the Isles (the Hebrides and Mann) which were known as Suðreyjar ("Southern Islands").[195]

- According to the Chronicle of Mann, Óláfr svarti was three years old at the time of his parents' marriage in 1176/1177. As such, one possibility is that the liaison between Guðrøðr and Findguala commenced at about the time of siege.[204]

- The marriage is dated to 1180 by the unreliable eighteenth-century Dublin Annals of Inisfallen.[218] Much of the information presented by this source appears to be derived from Expugnatio Hibernica, and it is possible that this is the origin of the marriage-date as well.[219]

- One of the witnesses recorded by this charter is a certain Gilla Críst described as Guðrøðr's "brother and foster-brother". This record appears to indicate that, although the two men were not related by blood, they had been nursed by the same mother.[237]

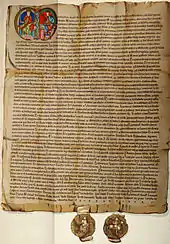

- The pictured piece depicts a seated bishop, holding a crozier with two hands, and wearing a chasuble as an outer garment. The simple horned mitre worn by this particular piece may be evidence that it dates to the mid twelfth century, when horns began to be positioned on the front and back, as opposed to the sides of the headdress.[242]

- The diocese is generally called Sodorensis in mediaeval sources.[244] This Latin term is derived from the Old Norse Suðreyjar,[245] and therefore means "of the Southern Isles", in reference to Mann and the Hebrides as opposed to the Northern Isles.[246]

- Nicholas Breakspeare, an Englishman who became Pope Adrian IV in 1154,[257] was instrumental in the foundation of the new archdiocese.[258] He apparently favoured Ingi as king over the latter's sibling co-rulers, Sigurðr and Eysteinn.[259] Guðrøðr's 1152/1153 stay in Scandinavia appears to have coincided with Eysteinn's absence from the region, when the latter was occupied in predatory campaigns in Orkney, Scotland, and England.[260] Eysteinn may have had Hebridean connections since saga evidence reveals that he first appeared in Norway claiming to be a son of Haraldr gilli, King of Norway and Bjaðǫk, a woman who seems to have borne a Gaelic name. Eysteinn was eventually recognised as Haraldr gilli's son, and it is conceivable that Eysteinn and Bjaðǫk had powerful relatives who backed their claims. In regard to Guðrøðr, it is possible that his cooperation with Ingi was undertaken in the context of avoiding having to deal with Eysteinn and his seemingly Irish or Hebridean kin.[261]

- Today Niðaróss is known as Trondheim.[264] Of the eleven dioceses, five were centred in Norway and six in colonies overseas (two in Iceland, one in Orkney, one in the Faroe Islands, one in Greenland, and one in the Isles).[262]

- The fact the poem also describes Rǫgnvaldr as a descendant of "Lochlann of the ships", Conn, and Cormac,—all apparent members of the Uí Néill—could indicate that Guðrøðr's apparent marriage to Sadb represents an earlier alliance with Muirchertach.[169]

- It is possible that seat of Manx royal power was located at Peel Castle before the seat moved to Castle Rushen in the thirteenth century.[296] The earliest evidence of ecclesiastical structures on the islet date to the tenth- and eleventh centuries.[297]

- Other potential candidates include Somairle and his son, Ragnall.[128]

Citations

- Dimock (1867) p. 265; Royal MS 13 B VIII (n.d.).

- Coira (2012); Stephenson (2008); Barrow (2006); Boardman (2006); Brown (2004); Bartlett (1999); McDonald (1997); McDonald (1995).

- Coira (2012).

- McDonald (2019); Crawford, BE (2014); Sigurðsson; Bolton (2014); Wadden (2014); Downham (2013); Kostick (2013); MacDonald (2013); Flanagan (2010); Jamroziak (2008); Martin (2008); Abrams (2007); McDonald (2007a); Davey, PJ (2006a); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Hudson (2005); McNamee (2005); Pollock (2005); Duffy (2004a); Duffy (2004b); Duffy (2004d); Sellar (2004); Woolf (2003); Beuermann (2002); Davey, P (2002); Freke (2002); Jennings, AP (2001); Oram (2000); Watt (2000); Thornton (1996); Watt (1994); Oram (1993); McDonald; McLean (1992); Freke (1990); Oram (1988); Power (1986); Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.).

- Rubin (2014).

- McLeod (2002).

- Ní Mhaonaigh (2018); Veach (2014); McDonald (2007a); Woolf (2005); Woolf (2004); Duffy (2004b); Woolf (2001); Duffy (1999); Thornton (1996); Duffy (1995); Duffy (1993); Duffy (1992); Duffy (1991).

- Duffy (2007); McDonald (2007a).

- McDonald (2007a); Purcell (2003–2004).

- Flanagan (1977).

- Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.).

- Williams, DGE (1997).

- Sigurðsson; Bolton (2014).

- Beuermann (2014); Williams, G (2007).

- Ekrem; Mortensen; Fisher (2006).

- Duffy (2005a).

- Veach (2018); Caldwell (2016); McDonald (2016); Rubin (2014); Veach (2014); Downham (2013); MacDonald (2013); Oram (2013); McDonald (2012); Oram (2011); Beuermann (2010); Beuermann (2009); Beuermann (2008); McDonald (2008); Duffy (2007); McDonald (2007a); McDonald (2007b); Woolf (2007); Duffy (2006); Macniven (2006); Power (2005); Salvucci (2005); Duffy (2004b); Thornton (1996); Gade (1994).

- Duffy (2004b); Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.).

- Boardman (2006).

- McDonald (2019); Crawford, BE (2014); Sigurðsson; Bolton (2014); Abrams (2007); Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005); Hudson (2005); McNamee (2005); Woolf (2003); Beuermann (2002); Jennings, AP (2001); Oram (2000).

- Oram (2000).

- Duffy (1995).

- Ní Mhaonaigh (2018); Veach (2014); Woolf (2005); Duffy (1993); Duffy (1992).

- Duffy (2007); Ó Mainnín (1999).

- Beuermann (2014).

- Caldwell (2016); McDonald (2016); Rubin (2014); Veach (2014); Downham (2013); Oram (2013); McDonald (2012); Beuermann (2010); McDonald (2008); Duffy (2007); McDonald (2007a); McDonald (2007b); Woolf (2007); Duffy (2004b); Gade (1994); Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.).

- Oram (2011); Macniven (2006).

- Kostick (2013).

- McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; Oram (2011) pp. xv tab. 4, xvi tab. 5; McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; Williams, G (2007) p. 141 ill. 14; Power (2005) p. 34 tab.; Brown (2004) p. 77 tab. 4.1; Sellar (2000) p. 192 tab. i; McDonald (1997) p. 259 tab.; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 200 tab. ii; Anderson (1922) p. 467 n. 2 tab.

- McDonald (2019) p. ix tab. 1; Oram (2011) pp. xv tab. 4, xvi tab. 5; McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1; Williams, G (2007) p. 141 ill. 14; Sellar (2000) p. 192 tab. i.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 27 tab. 1.

- McDonald (2016) p. 342; Wadden (2014) pp. 31–32; McDonald (2012) p. 157; McDonald (2007b) pp. 66, 75, 154; Anderson (1922) p. 137; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 60–61.

- Oram (1988) pp. 71–72, 79.

- Oram (2000) p. 60; Oram (1993) p. 116; Oram (1988) pp. 72, 79; Anderson (1908) p. 245; Lawrie (1910) p. 115 § 6; Howlett (1889) pp. 228–229.

- Oram (2011) p. xiii tab. 2.

- Oram (1988) p. 79.

- Oram (1993) p. 116; Oram (1988) p. 79.

- Oram (1993) p. 116; Oram (1988) p. 80.

- Oram (1988) p. 80.

- Munch; Goss (1874) p. 62; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- Oram (2011) pp. 86–89.

- Beuermann (2012) p. 5; Beuermann (2010) p. 102; Williams, G (2007) p. 145; Woolf (2005); Brown (2004) p. 70; Rixson (2001) p. 85.

- McDonald (2019) pp. viii, 59, 62–63, 93; Wadden (2014) p. 32; McDonald (2007b) pp. 67, 116; McDonald (1997) p. 60; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson (1922) p. 137; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 60–61.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 156 fig. 1b, 163 fig. 8e.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) p. 198.

- McDonald (2012) pp. 168–169, 182 n. 175; Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 165, 197.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 155, 168–173.

- McDonald (2012) p. 182 n. 175; Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) p. 178.

- Beuermann (2014) p. 85; Oram (2011) p. 113; Oram (2000) p. 73; Anderson (1922) p. 137; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 60–61.

- Oram (2000) p. 73.

- Oram (2011) p. 113; Oram (2000) p. 73.

- Beuermann (2014) p. 93 n. 43; Oram (2011) p. 113.

- Oram (2011) p. 113; Beuermann (2002) pp. 421–422; Oram (2000) p. 73.

- Rubin (2014) ch. 4 ¶ 18; Downham (2013) p. 172; McDonald (2012) p. 162; Oram (2011) p. 113; Beuermann (2010) pp. 106–107; Ekrem; Mortensen; Fisher (2006) p. 165; Hudson (2005) p. 198; Power (2005) p. 22; Beuermann (2002) p. 419, 419 n. 2; Jennings, AP (2001); Oram (2000) p. 73; Anderson (1922) p. 225; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 62–63.

- Crawford, BE (2014) pp. 70–72; Hudson (2005) p. 198; Johnsen (1969) p. 20; Anderson (1908) p. 245; Lawrie (1910) p. 115 § 6; Howlett (1889) pp. 228–229.

- Oram (2011) p. 108.

- Oram (2011) p. 113; McDonald (2007b) p. 67; Duffy (2004b).

- McDonald (2019) pp. 65, 74; Beuermann (2014) p. 85; Downham (2013) p. 171, 171 n. 84; Duffy (2006) p. 65; Sellar (2000) p. 191; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 259; Duffy (1993) pp. 41–42, 42 n. 59; Duffy (1991) p. 60; Oram (1988) pp. 80–81; Anderson (1922) p. 225; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 62–65.

- McDonald (2019) p. 74; McDonald (2007b) p. 92.

- Beuermann (2002) p. 423.

- Beuermann (2002) p. 423 n. 26.

- Clancy (2008) p. 36; Davey, P (2002) p. 95; Duffy (1993) p. 42; Oram (1988) p. 81; Anderson (1922) pp. 225–226; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 64–65.

- Oram (1988) p. 81.

- McDonald (2019) p. 65; Crawford, BE (2014) p. 74; Downham (2013) p. 171; McDonald (2012) p. 162; Oram (2011) p. 113; Abrams (2007) p. 182; McDonald (2007a) p. 66; McDonald (2007b) pp. 67, 85; Duffy (2006) p. 65; Oram (2000) pp. 69–70; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 259; Gade (1994) p. 199; Duffy (1993) p. 42; Oram (1988) p. 81; Anderson (1922) p. 226; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 64–67.

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 27 tab. 1, 58, 67, 85.

- McDonald (2007a) p. 51; Duffy (2007) p. 3; Thornton (1996) p. 95; Duffy (1993) p. 42; Duffy (1992) p. 126.

- Oram (1988) pp. 81, 85–86; Powicke (1978) pp. 45–46.

- Oram (2011) pp. 81–82, 113.

- Oram (2011) p. 113.

- McDonald (2007a) p. 59; McDonald (2007b) pp. 128–129 pl. 1; Rixson (1982) pp. 114–115 pl. 1; Cubbon (1952) p. 70 fig. 24; Kermode (1915–1916) p. 57 fig. 9.

- McDonald (2012) p. 151; McDonald (2007a) pp. 58–59; McDonald (2007b) pp. 54–55, 128–129 pl. 1; Wilson, DM (1973) p. 15.

- McDonald (2016) p. 337; McDonald (2012) p. 151; McDonald (2007b) pp. 120, 128–129 pl. 1.

- McDonald (2007a) pp. 58–60; McDonald (2007b) pp. 54–55; Wilson, DM (1973) p. 15, 15 n. 43.

- McDonald (2016) p. 343; McDonald (2007b) p. 204.

- McDonald (2016) pp. 341, 343–344; McDonald (2007b) pp. 56, 79, 204–205, 216, 221; McDonald (1995) p. 131; Rixson (1982) p. 127.

- McDonald (2016) pp. 341, 343; McDonald (2007a) pp. 59–60; McDonald (2007b) pp. 55–56, 128–129 pl. 2, 162, 204–205; McDonald (1995) p. 131; Rixson (1982) pp. 127–128, 146.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 204; Brownbill (1919) pp. 710–711 § 4; Oliver (1861) pp. 13–14; Document 1/14/1 (n.d.).

- McDonald (2016) p. 344.

- Duffy (2007) p. 2; O'Byrne (2005a); O'Byrne (2005c); Pollock (2005) p. 14; Duffy (2004c).

- Wadden (2014) pp. 29–31; Oram (2011) pp. 113, 120; McDonald (2008) p. 134; Duffy (2007) p. 2; McDonald (2007a) p. 71; O'Byrne (2005a); O'Byrne (2005b); O'Byrne (2005c); Duffy (2004c); Griffin (2002) pp. 41–42; Oram (2000) p. 73; Duffy (1993) pp. 42–43; Duffy (1992) pp. 124–125.

- Wadden (2014) pp. 18, 29–30, 30 n. 78; Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 1154.11; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 1154.11; Oram (2011) pp. 113, 120; Clancy (2008) p. 34; McDonald (2008) p. 134; Butter (2007) p. 141, 141 n. 121; Duffy (2007) p. 2; McDonald (2007a) p. 71; Pollock (2005) p. 14; Oram (2000) p. 73; Simms (2000) p. 12; Duffy (1992) pp. 124–125.

- Wadden (2014) pp. 30–31; Oram (2011) pp. 113, 120; McDonald (2008) p. 134; Duffy (2007) p. 2; McDonald (2007a) p. 71; McDonald (2007b) p. 118.

- Clancy (2008) p. 34.

- Griffin (2002) p. 42.

- Wadden (2014) p. 34; O'Byrne (2005a); Duffy (2004c); Griffin (2002) p. 42.

- French (2015) p. 23; Duffy (2004c).

- Stevenson (1841) p. 4; Cotton MS Domitian A VII (n.d.).

- Oram (2011) pp. 113–114, 120.

- McDonald (2019) p. 47; Wadden (2014) p. 32; Downham (2013) p. 172; Woolf (2013) pp. 3–4; Oram (2011) p. 120; Williams, G (2007) pp. 143, 145–146; Woolf (2007) p. 80; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 243–244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Rixson (2001) p. 85; Oram (2000) pp. 74, 76; McDonald (1997) pp. 52, 54–58; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 259–260, 260 n. 114; Duffy (1993) pp. 40–41; McDonald; McLean (1992) pp. 8–9, 12; Scott (1988) p. 40; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 231; Lawrie (1910) p. 20 § 13; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- McDonald (1997) p. 58; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 231; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- Jónsson (1916) p. 222 ch. 11; AM 47 Fol (n.d.).

- McDonald (2019) pp. 32, 74; Caldwell (2016) p. 354; McDonald (2012) pp. 153, 161; Oram (2011) p. 120; McDonald (2007a) pp. 57, 64; McDonald (2007b) p. 92; Barrow (2006) pp. 143–144; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Oram (2000) p. 76; McDonald (1997) pp. 52, 56; Duffy (1993) p. 43; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Scott (1988) p. 40; Rixson (1982) pp. 86–87; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) pp. 231–232; Lawrie (1910) p. 20 § 13; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- Oram (2000) p. 85 n. 127.

- McDonald (1997) p. 56 n. 48.

- McDonald (1997) p. 56.

- McDonald (2012) pp. 153, 161; Oram (2011) p. 121; McDonald (2007a) pp. 57, 64; McDonald (2007b) pp. 92, 113, 121 n. 86; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 244; Woolf (2004) p. 104; Oram (2000) p. 76; McDonald (1997) p. 56; Duffy (1993) p. 43; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 9; Rixson (1982) pp. 86–87, 151; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196; Anderson (1922) p. 239; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- McDonald (2012) pp. 159–161.

- McDonald (1997) p. 57.

- Oram (2011) p. 121.

- McDonald (1997) p. 57; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196.

- Oram (2000) p. 76; McDonald (1997) p. 57.

- Liber S. Marie de Calchou (1846) pp. III–VII; Diplomatarium Norvegicum (n.d.) vol. 19 § 38; Document 1/5/24 (n.d.).

- McDonald (2016) p. 341; Oram (2011) p. 12; Stephenson (2008) p. 12; McDonald (2007b) p. 113; Oram (2000) p. 76; Johnsen (1969) p. 22; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5; Anderson (1922) p. 246 n. 4; Bain (1881) p. 9 §§ 56, 60; Hunter (1844) pp. 155, 168; Diplomatarium Norvegicum (n.d.) vol. 19 § 35.

- Oram (2000) p. 76.

- Oram (2011) p. 121; Oram (2000) pp. 76–77.

- Taylor (2016) p. 250; Oram (2011) p. 121; Beuermann (2008); McDonald (2007a) p. 57; McDonald (2007b) p. 113; Power (2005) p. 24; Oram (2000) p. 77; Barrow (1995) pp. 11–12; McDonald; McLean (1992) p. 12 n. 5; Johnsen (1969) p. 22; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5; Liber S. Marie de Calchou (1846) pp. III–VII; Diplomatarium Norvegicum (n.d.) vol. 19 § 38; Document 1/5/24 (n.d.).

- Beuermann (2009); Beuermann (2008); McDonald (2007b) p. 113.

- Oram (2011) pp. 121–122.

- Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 60–61; Cotton MS Julius A VII (n.d.).

- Oram (2000) pp. 79–80.

- Oram (2011) pp. 118–122; Oram (2000) p. 80; Anderson; Anderson (1938) pp. 136–137, 136 n. 1, 189; Anderson (1922) p. 245.

- Oram (2011) pp. 118–122.

- Oram (2011) pp. 118–119; Oram (2000) p. 80.

- MacInnes (2019) p. 135; MacDonald (2013) p. 30 n. 51; Woolf (2013) p. 5; Oram (2011) pp. 118–119; Beuermann (2008); McDonald (2007b) p. 113; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; Oram (2000) p. 81; Barrow (1994).

- Woolf (2013) p. 5.

- Woolf (2013) pp. 5–6; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245.

- Storm (1899) p. 629.

- Oram (2011) p. 121; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) pp. 244–245; Oram (2000) p. 77; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 111.

- Finlay; Faulkes (2015) pp. 228–229 ch. 17; McDonald (2012) p. 162; Hollander (2011) p. 784 ch. 17; Beuermann (2010) p. 112, 112 n. 43; McDonald (2007b) p. 113; Forte; Oram; Pedersen (2005) p. 245; Power (2005) p. 24; Salvucci (2005) p. 182; Beuermann (2002) pp. 420–421 n. 8; Oram (2000) p. 77; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5; Anderson (1922) pp. 248–249; Jónsson (1911) pp. 609–610 ch. 17; Storm (1899) pp. 629–630 ch. 17; Unger (1868) pp. 772–773 ch. 17; Laing (1844) pp. 293–294 ch. 17.

- Storm (1977) pp. 116 § iv, 322 § viii, 475 § x; Johnsen (1969) p. 22; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5; Anderson (1922) p. 246; Vigfusson (1878) p. 360; Flateyjarbok (1868) p. 516.

- Beuermann (2010) p. 112.

- Antonsson; Crumplin; Conti (2007) p. 202.

- Ghosh (2011) p. 206.

- Ghosh (2011) p. 206; Beuermann (2010) p. 112.

- Beuermann (2002) p. 421 n. 10.

- McDonald (2012) p. 156; Power (2005) p. 28; McDonald (1997) p. 246; Ritchie (1997) p. 101.

- McDonald (2012) p. 156; Power (2005) p. 28; McDonald (1997) p. 246; Ritchie (1997) pp. 100–101; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) pp. 245 § 12, 249–250 § 12.

- McDonald (2012) p. 156; Bridgland (2004) p. 89; McDonald (1997) pp. 62, 246; Ritchie (1997) pp. 100–101; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 250 § 12.

- McDonald (2012) p. 156; Power (2013) p. 66; Power (2005) p. 28.

- McDonald (2016) p. 343; Beuermann (2014) p. 91; Power (2013) p. 66; McDonald (2012) pp. 153, 155; McDonald (2007b) p. 70, 201; Power (2005) p. 28; Duffy (2004b).

- Jennings, A (2017) p. 121; Oram (2011) p. 128; McDonald (2007a) p. 57; McDonald (2007b) pp. 54, 67–68, 85, 111–113; Sellar (2004); Sellar (2000) p. 189; Duffy (1999) p. 356; McDonald (1997) pp. 61–62; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150; Duffy (1993) p. 31; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197.

- The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1164.4; Oram (2011) p. 128; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1164.4; Oram (2000) p. 76; Duffy (1999) p. 356; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson (1922) pp. 253–254.

- Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 196 n. 5.

- Oram (2011) p. 128.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 46, 48; Oram (2011) pp. 128–129; McDonald (2007b) pp. 67–68, 85; Anderson (1922) pp. 258–259; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 74–75.

- Oram (2011) pp. 128–129; McDonald (2007a) p. 57; McDonald (2007b) pp. 67–68, 85; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150; Anderson (1922) pp. 258–259; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 74–75.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 85; Duffy (2004b).

- Sellar (2004); McDonald (1997) pp. 70–71; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150.

- McDonald (1997) pp. 70–71; Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 150, 260.

- McDonald (2019) pp. viii, 32; Coira (2012) pp. 57–58 n. 18; McDonald (1997) p. 60; Duffy (1993) p. 43; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197; Anderson (1922) p. 232; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 68–69.

- McDonald (1997) p. 60; Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197.

- Duncan; Brown (1956–1957) p. 197.

- Mac Lean (1985a) pp. 439–440; Mac Lean (1985b) pls. 88a–88b; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 212 § 95 figs. a–b; Reports of District Secretaries (1903) p. 305 fig.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 70; Mac Lean (1985a) p. 440; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) pp. 212–213 § 95; Kermode (1915–1916) p. 61; Reports of District Secretaries (1903) p. 306.

- Mac Lean (1985a) pp. 439–440; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) pp. 212–213 § 95.

- McDonald (2012) p. 155; McDonald (2007b) p. 70; Mac Lean (1985a) p. 439.

- Mac Lean (1985a) pp. 439–440; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 21.

- Mac Lean (1985a) p. 440; Argyll: An Inventory of the Monuments (1982) p. 21.

- McDonald (2019) pp. 46, 48; McDonald (2007b) pp. 85–86, 85 n. 88; Williams, DGE (1997) p. 150; Duffy (1993) p. 61, 61 n. 69; Anderson (1922) p. 305; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 76–79.

- McDonald (2007b) pp. 85–86.

- Williams, DGE (1997) pp. 150, 260–261, 260 n. 121.

- Duffy (1993) p. 61.

- Downham (2013) p. 178 tab.

- Duffy (1993) pp. 45, 61; Duffy (1992) pp. 128–129; Butler (1845) pp. 50–51 § 69.

- Oram (2000) p. 105.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 85 n. 88; Duffy (1993) p. 61, 61 n. 69.

- Duffy (2007) pp. 3–4; Oram (2000) pp. 74–75; Duffy (1993) p. 44; Duffy (1992) pp. 126–128.

- Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) pp. 145–146; Downham (2013) pp. 166, 171–172; McDonald (2008) p. 134; Duffy (2007) p. 3; McDonald (2007a) p. 52; Oram (2000) pp. 74–75; Duffy (1993) pp. 43–45; Duffy (1992) pp. 126–127; Duffy (1991) p. 67; Anderson (1922) p. 230–231; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 66–69.

- Oram (2000) p. 75; Duffy (1992) p. 126.

- Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) §§ 1154.12, 1154.13; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) §§ 1154.12, 1154.13; Duffy (1993) p. 42.

- The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1162.4; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1162.4; Duffy (2007) pp. 3–4; Oram (2000) p. 75; Duffy (1993) p. 44; Duffy (1992) p. 128.

- Duffy (1993) p. 44; Duffy (1992) p. 128.

- Annals of the Four Masters (2013a) § 1162.11; Annals of the Four Masters (2013b) § 1162.11; Duffy (2007) p. 4; Oram (2000) p. 75; Duffy (1993) p. 44; Duffy (1992) p. 128.

- The Annals of Ulster (2012) § 1162.5; The Annals of Ulster (2008) § 1162.5; Duffy (1993) p. 45.

- Duffy (2007) p. 4; Duffy (1993) pp. 44–45; Duffy (1992) p. 128.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) p. 157 fig. 2a, 163 fig. 8d, 187 fig. 14.

- McDonald (2019) p. 64; McDonald (2016) p. 342; Beuermann (2014) p. 93, 93 n. 45; Wadden (2014) pp. 32–33; Downham (2013) p. 172, 172 n. 86; Flanagan (2010) p. 195, 195 n. 123; Duffy (2007) p. 4; McDonald (2007a) p. 52; McDonald (2007b) pp. 68, 71, 171, 185; Oram (2000) p. 109 n. 24; Watt (2000) p. 24; McDonald (1997) pp. 215–216; Duffy (1993) p. 58; Duffy (1992) p. 127 n. 166; Flanagan (1989) p. 103; Power (1986) p. 130; Flanagan (1977) p. 59; Anderson (1922) pp. 296–297; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 76–77; Haddan; Stubbs (1873) p. 247.

- McDonald (2019) p. 60; Flanagan (2010) p. 195; McDonald (2007a) p. 52; McDonald (2007b) p. 71; Martin (2008) p. 135; Pollock (2005) p. 16 n. 76; Flanagan (1989) p. 103; Anderson (1922) p. 297 n. 1.

- Wadden (2014) p. 33.

- Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) p. 146; Duffy (1992) p. 128 n. 166.

- Pollock (2005) p. 16 n. 76.

- Downham (2013) p. 172; Duffy (2007) p. 4.

- Oram (2000) pp. 74–75.

- Oram (2011) pp. 113–114, 120; Oram (2000) pp. 74–76.

- Oram (2000) p. 75; McDonald (1997) pp. 55–56.

- Duffy (2007) pp. 2–3; Pollock (2005) p. 14, 14 n. 69; Oram (2000) p. 75; Duffy (1999) p. 356; Duffy (1993) pp. 31, 42–43.

- Duffy (2007) p. 3; McDonald (1997) pp. 55–56; Duffy (1993) p. 43.

- McDonald (1997) pp. 55–56.

- Oram (2011) p. 128; Oram (2000) p. 76.

- Williams, G (2007).

- Downham (2013) pp. 171–172.

- Downham (2013) pp. 171–172; Oram (2000) pp. 67, 76; Duffy (1993) pp. 40–41; Duffy (1992) pp. 121–122.

- Downham (2013) pp. 171–172; Oram (2000) p. 67.

- French (2015) p. 27; Simms (1998) p. 56.

- McDonald (2008) p. 134; Duffy (2007) p. 6; Duffy (2004b).

- Flanagan (2004b); Flanagan (2004c).

- Duffy (2007) pp. 4–5.

- Crooks (2005a); Flanagan (2004b).

- Flanagan (2004a); Flanagan (2004b); Duffy (1998) pp. 78–79; Duffy (1992) p. 131.

- Flanagan (2004a); Duffy (1998) pp. 78–79.

- Duffy (1998) p. 79; Duffy (1992) pp. 131–132.

- Caldwell; Hall; Wilkinson (2009) pp. 161 fig. 6c, 184 fig. 11, 189 fig. 16.

- Downham (2013) p. 157 n. 1; McDonald (2008) p. 135; Duffy (2007) p. 5; Duffy (2005b) p. 96; Purcell (2003–2004) p. 285; Duffy (1998) p. 79; Duffy (1993) pp. 46, 60; Duffy (1992) p. 132; Wright; Forester; Hoare (1905) pp. 213–215 (§ 17); Dimock (1867) pp. 256–258 (§ 17).

- Downham (2013) p. 157 n. 1.

- McDonald (2012) p. 152.

- Duffy (2005b) p. 96; Duffy (1998) p. 79; Duffy (1992) p. 132, 132 n. 184.

- Duffy (1992) p. 132, 132 n. 184.

- Duffy (2007) p. 5; Duffy (1992) p. 132.

- Song of Dermot and the Earl (2011) pp. 165, 167 (§§ 2257–2272); McDonald (2008) pp. 135–136, 135–136 n. 24; Duffy (2007) p. 5; Song of Dermot and the Earl (2010) pp. 164, 166 (§§ 2257–2272); Duffy (1992) p. 132; Wright; Forester; Hoare (1905) pp. 219–221 (§ 21); Dimock (1867) pp. 263–265 (§ 21).

- Duffy (2007) pp. 5–6; Purcell (2003–2004) p. 287; Duffy (1992) p. 132.

- McDonald (2012) p. 160; Barrett (2004).

- O'Byrne (2005) p. 469; Duffy (1992) p. 132.

- Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) pp. 145–146, 146 n. 80; Wyatt (2018) p. 797; Wyatt (2009) p. 391; McDonald (2008) pp. 134, 136; Duffy (2007) p. 6; McDonald (2007a) pp. 52, 63, 70; Pollock (2005) p. 15; Power (2005) p. 37; Purcell (2003–2004) p. 288, 288 n. 59; Gillingham (2000) p. 94; Duffy (1993) pp. 46–47, 59–60; Duffy (1992) pp. 132–133; Duffy (1991) p. 60; Wright; Forester; Hoare (1905) pp. 221–222 (§ 22); Dimock (1867) pp. 265–266 (§ 22).

- Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) p. 146; Anderson (1922) pp. 296–297; Munch; Goss (1874) pp. 76–77.

- Kostick (2013) ch. 6 ¶ 88.

- Duffy (2007) p. 7; O'Byrne (2005) p. 469; Duffy (1993) p. 47; Duffy (1992) p. 133.

- Downham (2013) p. 157.

- Duffy (2005b) p. 96; Flanagan (2004a); Simms (1998) p. 57.

- Strickland (2016) pp. 86, 357 n. 61.

- Strickland (2016) p. 86.

- Strickland (2016) p. 357 n. 61.

- McDonald (2008) pp. 135–136; McDonald (2007a) p. 52; McDonald (2007b) pp. 124–125; Duffy (1992) p. 133; Duffy (1991) p. 60.

- McDonald (2008) p. 136; McDonald (2007b) p. 125.

- Ní Mhaonaigh (2018) pp. 145–146; Veach (2018) p. 167; McDonald (2008) p. 136; McDonald (2007b) p. 125; Duffy (2005a); Duffy (2004a); Oram (2000) p. 105; Power (1986) p. 130.

- McDonald (2008) pp. 136–137; Crooks (2005b); Duffy (2005a); Duffy (2004a).

- McDonald (2019) p. 60; McDonald (2007b) p. 126; Duffy (1995) p. 25, n. 167; Duffy (1993) p. 58.

- McDonald (2008) pp. 137–138; McDonald (2007b) pp. 126–127; Duffy (1996) p. 7.

- Veach (2014) pp. 56–57; McDonald (2008) p. 136; McDonald (2007b) p. 126; Duffy (2005a); Duffy (2004a); Duffy (1995) p. 25 n. 167; Duffy (1993) p. 58, 58 n. 53; Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.) p. 11 § 2.5.9.

- McDonald (2007b) p. 126; Duffy (1995) p. 25 n. 167.

- McDonald (2008) p. 137; McDonald (2007b) pp. 126–127; Duffy (1995) p. 25; Duffy (1993) p. 58; Macdonald; McQuillan; Young (n.d.) pp. 10–12 §§ 2.5.8–2.5.10.

- McDonald (2008) p. 137; McDonald (2007b) pp. 126–127.