Rihand Dam

Rihand Dam also known as Govind Ballabh Pant Sagar, is the second largest dam of India by volume (storage) next only to Indira Sagar of Madhya Pradesh. The reservoir of Rihand Dam is called Govind Ballabh Pant Sagar and is India's largest artificial lake.[4] Rihand Dam is a concrete gravity dam located at Pipri in Sonbhadra District in Uttar Pradesh, India.[5] Its reservoir area is on the border of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. It is located on the Rihand River, a tributary of the Son River. The catchment area of this dam extends over Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh & Chhattisgarh whereas it supplies irrigation water in Bihar located downstream of the river.

| Rihand Dam | |

|---|---|

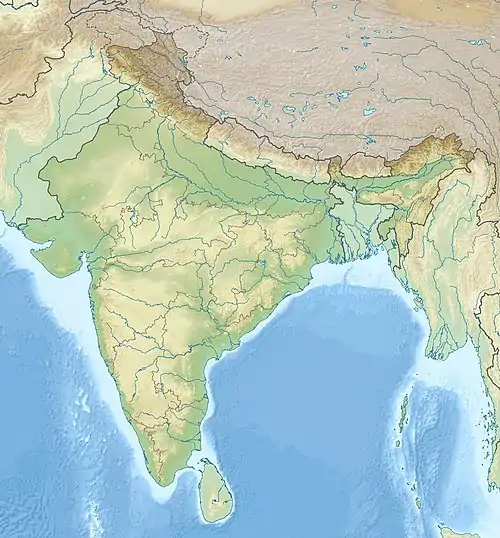

Location of Rihand Dam in Uttar Pradesh  Rihand Dam (India) | |

| Official name | Govind Ballabh Pant Sagar |

| Country | India |

| Location | Sonbhadra, Uttar Pradesh |

| Coordinates | 24°12′9″N 83°0′29″E |

| Construction began | 1953 |

| Opening date | 1962 |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Height | 91.46 m (300 ft) |

| Length | 934.45 m (3,066 ft)[1] |

| Reservoir | |

| Total capacity | 10.6 billion cubic metres |

| Active capacity | 8.9 billion cubic metres (314.34 tmc ft) |

| Inactive capacity | 1.7 billion cubic metres (60 tmc ft) |

| Catchment area | 13,333.26 km2 (5,148 sq mi)[2] |

| Power Station | |

| Turbines | 6 x 50 MW Francis-type |

| Installed capacity | 300 MW[3] |

Specifications

Govind Ballabh Pant Sagar is the largest man made lake in India. Rihand dam is a concrete gravity dam with a length of 934.45 m. The maximum height of the dam is 91.46 m and was constructed during period from 1954–62. The dam consists of 61 independent blocks and ground joints. The powerhouse is situated at the toe of the dam, with installed capacity of 300 MW (6 units of 50 MW each). The Intake Structure is situated between blocks no. 28 and 33. The Dam is in distress condition. It is proposed to carry out the rehabilitation works in the dam and the powerhouse.[6] The F.R.L. of the dam is 268.22 ft (81.75 m) and it impounds 8.6 Million Acre feet of water. The construction of the dam resulted in forced relocation of nearly 100,000 people [7]

Many super thermal power stations are located in the catchment area of the dam. These are Singrauli, Vindyachal, Rihand, Anpara & Sasan super thermal power stations and Renukoot thermal station. The high alkalinity run off water from the ash dumps (some are located in the reservoir area) of these coal-fired power stations ultimately collects in this reservoir enhancing its water alkalinity and pH range. Using high alkalinity water for irrigation converts the agriculture fields in to fallow Alkali soils.

Dams and Development

As the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru was determined to make India economically self-reliant and self-sufficient in its food production.[8] Nehru waged an aggressive dam building campaign, drastically expanding infrastructure left by the British Raj, who "had put down 75,000 miles of irrigation canals to water the subcontinent’s most valuable farmland."[8] Nehru believed dams held the key for growth and the achievement of his economic goals for India. At the opening of the Bhakra Dam in 1963, he referred to the dam as "the temple of a free India, at which I worship."[8] The taming of rivers throughout India marked the dawn of a new, independent and most importantly free India that would finally be able to make use of its resources on its terms, enriching its people in the process. To this day, India continues to build dams throughout to achieve these ambitious economic goals.

Background

Before the dam was built, Renukoot, the town in which it was built, was a primarily agrarian locale. The region lacked basic modern features such as adequate transportation and roads, and electricity, but the prospect of arable land provided a boon for local villages to farm and sustain themselves. Authorities recognized the potential for growth in the region, as Sonbhadra was home to vast natural resources including coal, forests with various types of trees such as sal, bamboo, khair, and salal. Building a dam to harness the power of the Rihand would represent a first step in developing the region and bringing industry to it.[9]

British colonial authorities were interested in building a dam on the Rihand River as early as 1940.[9] The construction of a dam had the potential to improve irrigation in the region, as well, and held the promise of generating hydro-electric power. In 1952, the Independent Indian government sanctioned survey work; construction began in 1954 and was completed in 1962.

Social Impact

The construction of the Rihand Dam has catalyzed the transformation of the Singrauli region from an agrarian society into an industrial one. Greenpeace found “the social and demographic profile of the area has undergone a significant transformation with the massive industrial changes to the landscape.”[10] This influx of industry, primarily energy and manufacturing interests, has allowed the region to grow and power the growing Indian economy. Despite this growth, serious questions over the nature of these development projects remain, as tens of thousands of locals were forced to relocate for the construction of the Rihand Dam, and tens of millions throughout India as a consequence of the construction of dams throughout the country.[11][12][13][14] Critics allege that growth takes priority over human welfare, with safety precautions in work environments severely lacking and little care taken to protect the environment. Despite being built 60 years ago, these impacts are longstanding.

Economic Impact

In terms of achieving economic growth and development for Indian authorities and business interests, the Rihand Dam has been an unmitigated success. The construction of the dam allowed for the Singrauli region to expand rapidly in the ensuing years, with various industries emerging in the region. Local industries produce a wide range of goods, such as commercial vehicles, mining equipment, locomotives, telecommunication cables, and power generation equipment. To facilitate this growth, the Indian government subsequently purchased thousands of acres of land in neighboring villages and throughout the district of Madhya Pradesh to sell to industrialists. These plants required tens of thousands of workers to operate them, creating opportunities for Indians to earn better wages.[9] Singh points out firms did not hire the locals displaced by the dam. Instead, the government and companies chose to hire laborers from other regions within India.

As these other industries arose, coal remained the driving force behind the expansion of the Singrauli economy. With nine billion tons of coal reserves, Singrauli has long been viewed as “India’s energy capital;” its vast coal reserves, discovered in 1840, have long attracted mining companies and state planners sought to harvest this resource to power the industry that eventually came to dominate the area.[10] Coal mining increased precipitously in the decades after the construction of Rihand; By 1980, production totaled around six million tons and at the time Singh wrote his article, was expected to reach 30 million tons by 1995 and eventually eclipse 75 million tons amounting to more than half of India’s entire production of coal in 1983.[9]

Environmental Impact

As the Indian government’s primary concern has been to foster growth, it has often chosen the most expedient route to achieve its goals, at the expense of the environment. The construction of the Rihand Dam was only the beginning of industrialization in the Singrauli region. As state and private entities have continued to develop the region, pollution has increased, threatening the environment and wellbeing of residents, while taking valuable farmland.[10] Pollution from industry has harmed the health of local residents, as well. Fluoride contamination in the dam’s reservoir water pollutes groundwater, consequently affecting drinking water and agriculture. Researchers estimate that more than 60 million people from 17 states deal with the effects of dental, skeletal, or non-skeletal fluorosis, a chronic condition caused by excessive intake of fluorine compounds, marked by mottling of the teeth and, if severe, calcification of the ligaments. While some fluoride contamination may be caused by natural processes, human activities such as coal and mineral mining and the operation of thermal power plants have led to increased pollution.[15] Coupled with increased demands for water, more residents are consequently forced to drink this contaminated water.

Despite the ramifications of this industry, the Indian government has often willfully ignored the consequences. On January 13, 2010, the Ministry of Environment and Forests halted all mining in the region until environmental concerns were addressed. Indian officials from the Central Pollution Control Board and researchers from the Indian Institute of Technology found the area to be “critically polluted,” but mining was allowed to continue in July 2011.[10] This tension between immediate growth and environmental safeguards continues, as Indian authorities continue to push for more money (energy production and economic growth), ignoring the concerns of local governments and the lives of these people.

Forced Relocation

The most significant consequence of the construction of the Rihand Dam has been the internal displacement of local tribes. Development projects throughout India have led to the forced migration of tens of millions with India, creating a phenomenon that Indian environmental activist Parshuram Ray dubs “Development Induced Displacement.” After British colonial rule, the Indian government ambitiously sought to develop their newly independent country. The state facilitated the construction of dams, mega dams, mines, factories, and irrigation projects.[16] Despite governments making promises to these groups, little action has been taken to alleviate their suffering. Researchers estimate the number of displaced persons for dam projects across India to top 50 million and believe official statistics often understate the true level of destruction that these projects bring to mask their true cost.[16] Despite this forced relocation across India being rather commonplace, the government is most likely violating its own constitution, which guarantees its citizens a right to life.[14] But there is little political will to address or contest this, and authorities have no impetus to change their practices.

By 1960, the dam was nearing completion and almost ready to be put into use. 108 villages containing 50,000 people were immediately put at risk, but the government provided no assistance to assist their relocation. Instead, in May–June 1961, 20,000 locals went to protest the lack of government action to protect their welfare. Instead of acknowledging the protestors' concerns, the local Deputy Commissioner instead sent two thousand policemen to force the protestors home and ordered the dam gates to be closed, forcing people from their homes with only 24 hours of notice.[9] The same villagers were then forced to relocate in 1965 when coal mines opened, again in 1980 when the National Thermal Power Corporation broke ground on a thermal power project, and once more in 2009, when the Essar Power MP broke ground on a new plant. Despite being displaced as many as five times, families forced out by the construction of Rihand never found a new permanent home.[13]

Enduring such upheavals caused psychic harm in addition to the precipitous drop in living standards. Parshuram Ray goes into further detail when discussing the traumas caused by displacement:

The long drawn out, dehumanising [sic], disempowering and painful process of displacement has led to widespread traumatic psychological and socio-cultural consequences. It causes dismantling of production systems, desecration of ancestral sacred zones or graves and temples, scattering of kinship groups and family systems, disorganization of informal social networks that provide mutual support, weakening of self-management and social control and disruption of trade and market links etc… Essentially, the very cultural identity of the displaced community and individual is subjected to massive onslaught leading to very severe physiological stress and psychological trauma.[13]

Despite these very real traumas, the national government has failed to alleviate suffering in any meaningful way. Planners are not pressured by governments to plan for these consequences. The disruption in communities that these projects cause also quash potential political unrest or protest, as people can no longer rely on their destroyed networks.

Within these forced displacements, gender and economic issues bring more hardship. Indian law provides no relief to displaced women and women do not enjoy the same economic protections and freedoms that men do. Women are consequently forced to rely on male members of the household, as they are not entitled to any benefits the government offers. For tribes that have only lived off the land, shifting to a market economy is also a massive shock because they have never engaged in such a system.[13]

The constant and forced resettlement, in addition to being cruel and callous, threatens gains from these projects such as the Rihand Dam. The intergenerational traumas wound those forced to leave, but also disrupt stable villages and economies, ultimately dooming millions of future Indians to poverty.

The Push for Sustainable Growth

The construction of the Rihand Dam falls into a larger paradigm, as its construction has arguably propagated more problems than it has benefits. Writing in 2003, reporter Diane Raines Ward found:

A 1995 Indian Environment Ministry report revealed that 87 percent of India’s river-valley projects did not meet required safeguards. Recent reports show that larger dam reservoirs are silting up at rates far higher than assumed when the projects were built, that the life span of major Indian dams is likely to be only two-thirds of their projected life, and that every dam built in India during the last 15 years has violated various environmental regulations — from siltation and soil erosion, to the neglect of health, seismological, forest, wildlife, human, and clean water issues.[8]

As the world's largest democracy and second most populous country, Indian leaders must balance the goals of economic development with democratic ideals and the overall welfare of its people. While economic growth is attractive, it alone cannot increase the welfare of Indian people and growth pursued in this matter will not only not bring about long term growth, but it will kill people in the process and make India uninhabitable. Amartya Sen and Jean Drèze discuss these tensions, acknowledging "issues of economic development in India have to be seen in the larger context of the demands of democracy and social justice."[17] They push back against India's preoccupation with simply increasing its GDP per capita, as such a metric is limited in scope and fails to capture what is being done with that increase in wealth, who is benefitting from it, and whether people's lives are materially improving. They write:

Those who dream about India becoming an economic superpower, even with its huge proportion of undernourished children, lack of systematic health care, extremely deficient school education, and half the homes without toilets (forcing half of all Indians to practise open defecation), have to reconsider not only the reach of their understanding of the mutual relationship between growth and development, but also their appreciation of the demands of social justice, which is integrally linked with the expansion of human freedoms.[17]

Sen and Drèze push for sustainable growth; growth that is environmentally sustainable but socially sustainable so that the gains are not zero sum. Instead, sustainable growth maximizes the number of individuals who benefit, while minimizing the hardship and complications that arise from economic expansion. The construction of the Rihand Dam and the destruction it caused in the lives of hundreds of thousands exemplify the need for such an approach. This is achievable, but requires patience and a commitment to working within this framework. NGOs working with villages and small towns to bring back water collection methods speak to the efficacy of such an approach, showing mega-projects are not the only solution.[8] Local level provisions like these can often solve the problem more effectively, as locals are more privy to their own needs and how their immediate area operates.

By 2019, various Indian companies such as the Shapoorji Pallonji Group and ReNew Power had won the rights to invest ₹7.5 billion ($106 million) to build solar panels with a capacity of 150MW on the Rihand Dam.[18] A project like this shows not only how sustainable policies and projects are possible, but existing infrastructure can be used in new and different ways to yield more benefit.

See also

References

- "India: National Register of Large Dams 2009" (PDF). Central Water Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- UPJVNL. "Uttar Pradesh Jal Vidyut Nigam Limited". Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Rihand Power Station, Pipri, District : Sonebhadra (UP)". UPDESCO. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- "Kathiawar-Gir dry deciduous forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "Rihand Dam". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- "Rehabilitation of Rihand dam". Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- B. Terminski, Development-Induced Displacement: Theoretical Frameworks and Current Challenges, Geneva, 2013

- "The Dammed ~ Water Wants: A History of India's Dams | Wide Angle | PBS". Wide Angle. 18 September 2003. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Singh, Satyajit Kumar (1985). "From the Dam to the Ghettos: The Victims of the Rihand Dam". Economic and Political Weekly. 20 (39): 1643–1644. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4374864.

- "Singrauli: The Coal Curse". Greenpeace India. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Internal displacement in India: causes, protection and dilemmas | Forced Migration Review". www.fmreview.org. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Fernandes, Walter (October 2013). "Internally Displaced Persons and Northeast India". International Studies. 50 (4): 287–305. doi:10.1177/0020881717714900. ISSN 0020-8817. S2CID 158254014.

- Ray, Parshuram (August 2000). "Internal Displacement in India: Causes, Protection and dilemmas". Forced Migration Review. 8.

- Sadual, Manoj Kumar (January 2015). "Tribal Displacement in the Name of Development in India: Legal Intervention and Redressal". International Journal of Management and Social Sciences. 3: 575–590.

- Usham, A. L.; Dubey, C. S.; Shukla, D. P.; Mishra, B. K.; Bhartiya, G. P. (April 2018). "Sources of Fluoride Contamination in Singrauli with Special Reference to Rihand Reservoir and its Surrounding". Journal of the Geological Society of India. 91 (4): 441–448. doi:10.1007/s12594-018-0877-y. ISSN 0016-7622. S2CID 134250100.

- Kumar, Sudesh; Mishra, Anindya J. (2018). "Development-Induced Displacement in India: An Indigenous Perspective". Journal of Management and Public Policy. 10 (1): 25. doi:10.5958/0976-0148.2018.00008.2. ISSN 0976-013X.

- Drèze, Jean (11 August 2013). An uncertain glory : India and its contradictions. Sen, Amartya, 1933-. Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 978-0-691-16079-5. OCLC 846540422.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "UP government clears state's first floating solar power plant on Rihand Dam". The Economic Times. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.