Greeks in Turkey

The Greeks in Turkey (Turkish: Rumlar) constitute a small population of Greek and Greek-speaking Eastern Orthodox Christians who mostly live in Istanbul, as well as on the two islands of the western entrance to the Dardanelles: Imbros and Tenedos (Turkish: Gökçeada and Bozcaada). Greeks are one of the four ethnic minorities officially recognized in Turkey by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, together with Jews, Armenians,[6][7][8] and Bulgarians.[9][10][11]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,000–5,000 (0.006% of population)[1][2][3] (not incl. Muslim Greeks[4][5] or Greek Muslims) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Istanbul, Izmir, Çanakkale (Gökçeada and Bozcaada) | |

| Languages | |

| Greek (first language of the majority), Turkish (first language of the minority or second language) | |

| Religion | |

| Greek Orthodoxy | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Greek Muslims, Pontic Greeks, Antiochian Greeks |

| Part of a series on |

| Greeks |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

(Ancient Byzantine Ottoman) |

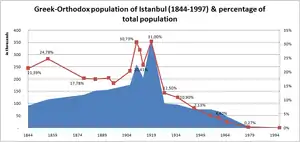

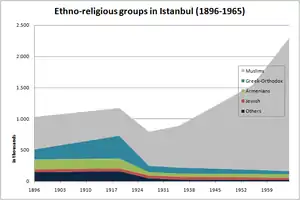

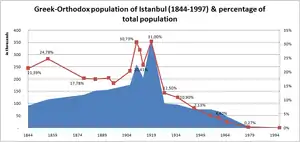

They are the remnants of the estimated 200,000 Greeks who were permitted under the provisions of the Convention Concerning the Exchange of Greek and Turkish Populations to remain in Turkey following the 1923 population exchange,[12] which involved the forcible resettlement of approximately 1.5 million Greeks from Anatolia and East Thrace and of half a million Turks from all of Greece except for Western Thrace. After years of persecution (e.g. the Varlık Vergisi and the Istanbul Pogrom), emigration of ethnic Greeks from the Istanbul region greatly accelerated, reducing the Greek minority population from 119,822 before the attack[13] to about 7,000 by 1978.[14] The 2008 figures released by the Turkish Foreign Ministry places the current number of Turkish citizens of Greek descent at the 3,000–4,000 mark.[2] However, according to the Human Rights Watch the Greek population in Turkey is estimated at 2,500 in 2006. The Greek population in Turkey is collapsing as the community is now far too small to sustain itself demographically, due to emigration, much higher death rates than birth rates and continuing discrimination.[15]

Since 1924, the status of the Greek minority in Turkey has been ambiguous. Beginning in the 1930s, the government instituted repressive policies forcing many Greeks to emigrate. Examples are the labour battalions drafted among non-Muslims during World War II, as well as the Fortune Tax (Varlık Vergisi) levied mostly on non-Muslims during the same period. These resulted in financial ruination and death for many Greeks. The exodus was given greater impetus with the Istanbul Pogrom of September 1955 which led to thousands of Greeks fleeing the city, eventually reducing the Greek population to about 7,000 by 1978 and to about 2,500 by 2006. According to the United Nations, this figure was much smaller in 2012 and reached 2,000.

A minority of Muslim Pontic Greek speakers, using a dialect called "Romeyka" or "Ophitic", still live in the area around Of.[16][17][18]

Name

The Greeks of Turkey are referred to in Turkish as Rumlar, meaning "Romans". This derives from the self-designation Ῥωμαῖος (Rhomaîos, pronounced ro-ME-os) or Ρωμιός (Rhomiós, pronounced ro-mee-OS or rom-YOS) used by Byzantine Greeks, who were the continuation of the Roman Empire in the east.

The ethnonym Yunanlar is exclusively used by Turks to refer to Greeks from Greece and not for the population of Turkey.

In Greek, Greeks from Asia Minor are referred to as Greek: Μικρασιάτες or Greek: Ανατολίτες (Mikrasiátes or Anatolítes, lit. "Asia Minor-ites" and "Anatolians"), while Greeks from Pontos (Pontic Greeks) are known as Greek: Πόντιοι (Póntioi).

Greeks from Istanbul are known as Greek: Κωνσταντινουπολίτες (Konstantinoupolítes, lit. "Constantinopolites"), most often shortened to Greek: Πολίτες (Polítes, pronounced po-LEE-tes). Those who arrived during the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey are also referred to as Greek: Πρόσφυγες (Prósfyges, i. e. "Refugees").

History

Background

Greeks have been living in what is now Turkey continuously since the middle 2nd millennium BC. Following upheavals in mainland Greece during the Bronze Age Collapse, the Aegean coast of Asia Minor was heavily settled by Ionian and Aeolian Greeks and became known as Ionia and Aeolia. During the era of Greek colonization from the 8th to the 6th century BC, numerous Greek colonies were founded on the coast of Asia Minor, both by mainland Greeks as well as settlers from colonies such as Miletus. The city of Byzantium, which would go on to become Constantinople and Istanbul, was founded by colonists from Megara in the 7th century BC.

Following the conquest of Asia Minor by Alexander the Great, the rest of Asia Minor was opened up to Greek settlement. Upon the death of Alexander, Asia Minor was ruled by a number of Hellenistic kingdoms such as the Attalids of Pergamum. A period of peaceful Hellenization followed, such that the local Anatolian languages had been supplanted by Greek by the 1st century BC. Asia Minor was one of the first places where Christianity spread, so that by the 4th century AD it was overwhelmingly Christian and Greek-speaking. For the next 600 years, Asia Minor and Constantinople, which eventually became the capital of the Byzantine Empire, would be the centers of the Hellenic world, while mainland Greece experienced repeated barbarian invasions and went into decline.

Following the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the Seljuk Turks swept through all of Asia Minor. While the Byzantines would recover western and northern Anatolia in subsequent years, central Asia Minor was settled by Turkic peoples and never again came under Byzantine rule. The Byzantine Empire was unable to stem the Turkic advance, and by 1300 most of Asia Minor was ruled by Anatolian beyliks. Smyrna (Turkish: İzmir) fell in 1330, and Philadelphia (Turkish: Alaşehir), fell in 1398. The last Byzantine Greek kingdom in Anatolia, the Empire of Trebizond, covering the Black Sea coast of north-eastern Turkey to the border with Georgia, fell in 1461.

Ottoman Empire

Constantinople fell in 1453, marking the end of the Byzantine Empire. Beginning with the Seljuk invasion in the 11th century, and continuing through the Ottoman years, Anatolia underwent a process of Turkification, its population gradually changing from predominantly Christian and Greek-speaking to predominantly Muslim and Turkish-speaking.

A class of moneyed ethnically Greek merchants (they commonly claimed noble Byzantine descent) called Phanariotes emerged in the latter half of the 16th century and went on to exercise great influence in the administration in the Ottoman Empire's Balkan domains in the 18th century. They tended to build their houses in the Phanar quarter of Istanbul in order to be close to the court of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, who under the Ottoman millet system was recognized as both the spiritual and secular head (millet-bashi) of all the Orthodox subjects (the Rum Millet, or the "Roman nation") of the Empire, often acting as archontes of the Ecumenical See. For all their cosmopolitanism and often western (sometimes Roman Catholic) education, the Phanariots were aware of their Hellenism; according to Nicholas Mavrocordatos' Philotheou Parerga: "We are a race completely Hellenic".[20]

The first Greek millionaire in the Ottoman era was Michael Kantakouzenos Shaytanoglu, who earned 60.000 ducats a year from his control of the fur trade from Russia;[21] he was eventually executed on the Sultan's order. It was the wealth of the extensive Greek merchant class that provided the material basis for the intellectual revival that was the prominent feature of Greek life in the second half of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. Greek merchants endowed libraries and schools; on the eve of the Greek War of Independence the three most important centres of Greek learning, schools-cum-universities, were situated in Chios, Smyrna and Aivali, all three major centres of Greek commerce.[22]

The outbreak of the Greek War of Independence in March 1821 was met by mass executions, pogrom-style attacks, the destruction of churches, and looting of Greek properties throughout the Empire. The most severe atrocities occurred in Constantinople, in what became known as the Constantinople Massacre of 1821. The Orthodox Patriarch Gregory V was executed on April 22, 1821 on the orders of the Ottoman Sultan, which caused outrage throughout Europe and resulted in increased support for the Greek rebels.[23]

By the late 19th and early 20th century, the Greek element was found predominantly in Constantinople and Smyrna, along the Black Sea coast (the Pontic Greeks) and the Aegean coast, the Gallipoli peninsula and a few cities and numerous villages in the central Anatolian interior (the Cappadocian Greeks). The Greeks of Constantinople constituted the largest Greek urban population in the Eastern Mediterranean.[24]

In the first half of 1914, the Ottoman authorities expelled more than 100,000 Ottoman Greeks to Greece.[25]

World War I and its aftermath

Given their large Greek populations, Constantinople and Asia Minor featured prominently in the Greek irredentist concept of Megali Idea (lit. "Great Idea") during the 19th century and early 20th century. The goal of Megali Idea was the liberation of all Greek-inhabited lands and the eventual establishment of a successor state to the Byzantine Empire with Constantinople as its capital. The Greek population amounted to 1,777,146 (16.42% of population during 1910).[26]

During World War I and its aftermath (1914–1923), the government of the Ottoman Empire and subsequently the Turkish National Movement, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, instigated a violent campaign against the Greek population of the Empire.[27] The campaign included massacres, forced deportations involving death marches, and summary expulsions. According to various sources, several hundreds of thousand Ottoman Greeks died during this period.[28] Some of the survivors and refugees, especially those in Eastern provinces, took refuge in the neighbouring Russian Empire.

Following Greece's participation on the Allied side in World War I, and the participation of the Ottoman Empire on the side of the Central Powers, Greece received an order to land in Smyrna by the Triple Entente as part of the planned partition of the Ottoman Empire.

On May 15, 1919, twenty thousand[29] Greek soldiers landed in Smyrna, taking control of the city and its surroundings under cover of the Greek, French, and British navies. Legal justifications for the landings was found in the article 7 of the Armistice of Mudros, which allowed the Allies "to occupy any strategic points in the event of any situation arising which threatens the security of Allies."[30] The Greeks of Smyrna and other Christians greeted the Greek troops as liberators. By contrast, the majority of the Muslim population saw them as an invading force.

Subsequently, the Treaty of Sèvres awarded Greece Eastern Thrace up to the Chatalja lines at the outskirts of Constantinople, the islands of Imbros and Tenedos, and the city Smyrna and its vast hinterland, all of which contained substantial Greek populations.

During the Greco-Turkish War, a conflict which followed the Greek occupation of Smyrna[31][32] in May 1919 and continued until the Great Fire of Smyrna in September 1922, atrocities were perpetrated by both the Greek and Turkish armies.[33][34] For the massacres that occurred during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922, British historian Arnold J. Toynbee wrote that it was the Greek landings that created the Turkish National Movement led by Mustafa Kemal:[35] "The Greeks of 'Pontus' and the Turks of the Greek occupied territories, were in some degree victims of Mr. Venizelos's and Mr. Lloyd George's original miscalculations at Paris."

After the end of the Greco-Turkish War, most of the Greeks remaining in the Ottoman Empire were transferred to Greece under the terms of the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey. The criteria for the population exchange were not exclusively based on ethnicity or mother language, but on religion as well. That is why the Karamanlides (Greek: Καραμανλήδες; Turkish: Karamanlılar), or simply Karamanlis, who were a Turkish-speaking (while they employed the Greek alphabet to write it) Greek Orthodox people of unclear origin, were deported from their native regions of Karaman and Cappadocia in Central Anatolia to Greece as well. On the other hand, Cretan Muslims who were part of the exchange were re-settled mostly on the Aegean coast of Turkey, in areas formerly inhabited by Christian Greeks. Populations of Greek descent can still be found in the Pontos, remnants of the former Greek population that converted to Islam in order to escape the persecution and later deportation. Though these two groups are of ethnic Greek descent, they speak Turkish as a mother language and are very cautious to identify themselves as Greeks, due to the hostility of the Turkish state and neighbours towards anything Greek.

Republic of Turkey

Due to the Greeks' strong emotional attachment to their first capital as well as the importance of the Ecumenical Patriarchate for Greek and worldwide orthodoxy, the Greek population of Constantinople was specifically exempted and allowed to stay in place. Article 14 of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) also exempted Imbros and Tenedos islands from the population exchange and required Turkey to accommodate the local Greek majority and their rights. For the most part, the Turks disregarded this agreement and implemented a series of contrary measures which resulted in a further decline of the Greek population, as evidenced by demographic statistics.

In 1923, the Ministry of Public Works asked from the private companies in Turkey to prepare lists of employees with their religion and later ordered them to fire the non-Muslim employees and replace them with Muslim Turks.[36] In addition, a 1932 parliamentary law, barred Greek citizens living in Turkey from a series of 30 trades and professions from tailoring and carpentry to medicine, law and real estate.[37] In 1934, Turkey created the Surname Law which forbade certain surnames that contained connotations of foreign cultures, nations, tribes, and religions. Many minorities, including Greeks, had to adopt last names of a more Turkish rendition.[38][39][40][41] As from 1936, Turkish became the teaching language (except the Greek language lessons) in Greek schools.[42] The Wealthy Levy imposed in 1942 also served to reduce the economic potential of Greek businesspeople in Turkey.[43] When the Axis attacked on Greece during WW2 hundreds of volunteers from the Greek community of Istanbul went to fight in Greece with the approval of Turkish authorities.[44]

In 6–7 September 1955 an anti-Greek pogrom were orchestrated in Istanbul by the Turkish military's Tactical Mobilization Group, the seat of Operation Gladio's Turkish branch; the Counter-Guerrilla. The events were triggered by the news that the Turkish consulate in Thessaloniki, north Greece—the house where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk was born in 1881—had been bombed the day before.[43] A bomb planted by a Turkish usher of the consulate, who was later arrested and confessed, incited the events. The Turkish press conveying the news in Turkey was silent about the arrest and instead insinuated that Greeks had set off the bomb. Although the mob did not explicitly call for Greeks to be killed, over a dozen people died during or after the pogrom as a result of beatings and arson. Jews, Armenians and others were also harmed. In addition to commercial targets, the mob clearly targeted property owned or administered by the Greek Orthodox Church. 73 churches and 23 schools were vandalized, burned or destroyed, as were 8 asperses and 3 monasteries.

The pogrom greatly accelerated emigration of ethnic Greeks from Turkey, and the Istanbul region in particular. The Greek population of Turkey declined from 119,822 persons in 1927,[13] to about 7,000 by 1978. In Istanbul alone, the Greek population decreased from 65,108 to 49,081 between 1955 and 1960.[13]

In 1964 Turkish prime minister İsmet İnönü unilaterally renounced the Greco-Turkish Treaty of Friendship of 1930 and took actions against the Greek minority that resulted in massive expulsions.[45][46] Turkey enforced strictly a long‐overlooked law barring Greek nationals from 30 professions and occupations. For example, Greeks could not be doctors, nurses, architects, shoemakers, tailors, plumbers, cabaret singers, iron-smiths, cooks, tourist guides, etc.[45] Many Greeks were ordered to give up their jobs after this law.[47] Also, Turkish government ordered many Greek‐owned shops to close leaving many Greek families destitute.[45] In addition, Turkey has suspended a 1955 agreement granting unrestricted travel facilities to nationals of both countries. A number of Greeks caught outside Turkey when this suspension took effect and were unable to return to their homes at Turkey.[45] Moreover, Turkey once again deported many Greeks. They were given a week to leave the country, and police escorts saw to it that they make the deadline. Deportees protested that it was impossible to sell businesses or personal property in so short a time. Most of those deported were born in Turkey and they had no place to go in Greece.[45] Greeks had difficulty receiving credit from banks. Those expelled, in some cases, could not dispose of their property before leaving.[47] Furthermore, it forcefully closed the Prinkipo Greek Orthodox Orphanage,[48][49][50] the Patriarchate's printing house[47] and the Greek minority schools on the islands of Gökçeada/Imbros[51] and Tenedos/Bozcaada.[52] Furthermore, the farm property of the Greeks on the islands were taken away from their owners.[52] Moreover, university students were organizing boycotts against Greek shops.[47] Teachers of schools maintained by the Greek minority complained of frequent "inspections" by squads of Turkish officers inquiring into matters of curriculum, texts and especially the use of the Greek language in teaching.[47] In late 1960, the Turkish treasure seized the properties of the Balıklı Greek Hospital. The hospital sued the treasury on the ground that the transfer of its property was illegal, but the Turkish courts were in favor of the Turkish treasure.[53] On August 4, 2022, a fire broke out on the roof of the Balıklı Greek Hospital. The roof was completely destroyed and the upper floor was also destroyed except for the exterior walls. However, the ground floor of the hospital remained unscathed from the fire.

In 1965 the Turkish government established on Imbros an open agricultural prison for Turkish mainland convicts; farming land was expropriated for this purpose. Greek Orthodox communal property was also expropriated and between 1960 and 1990 about 200 churches and chapels were reportedly destroyed. Many from the Greek community on the islands of Imbros and Tenedos responded to these acts by leaving.[54] In addition, at the same year the first mosque was built in the island. It was named Fatih Camii (Conqueror's Mosque) and was built on an expropriated Greek Orthodox communal property at the capital of the island.[55]

In 1991, Turkish authorities ended the military "forbidden zone" status on the island of Imbros.[54]

In 1992, Panimbrian Committee mentioned, that members of the Greek community are "considered by the authorities to be second class citizens" and that the local Greeks are afraid to express their feelings, to protest against certain actions of the authorities or the Turkish settlers, or even to allow anybody to make use of their names when they give some information referring to the violation of their rights, fearing the consequences which they will have to face from the Turkish authorities.[54] The same year the Human Rights Watch report concluded that the Turkish government has denied the rights of the Greek community on Imbros and Tenedos in violation of the Lausanne Treaty and international human rights laws and agreements.[54]

In 1997, the Turkish state seized the Prinkipo Greek Orthodox Orphanage which had been forcefully closed in 1964.[56] After many years of court battles, Turkey returned the property to the Greek community in 2012.[57][56]

In August 2002, a new law was passed by the Turkish parliament to protect the minorities rights, because of Turkey's EU candidacy. With this new law, it prevented the Turkish treasury from seizing community foundations properties.[53]

In 15 August 2010, a ritual have held for the Assumption of Mary at the Sumela Monastery after a 88 years old ban. This annual ritual continues, although it often sparks debate in Turkey for “keeping foreign traditions alive on the day Trabzon was captured by the Turks.”.[58]

Current situation

Today most of the remaining Greeks live in Istanbul. In the Fener district of Istanbul where the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople is located, fewer than 100 Greeks live today. A handful also live in other cities of Anatolia. Most are elderly.

Another location where the Greek community lives is the islands Imbros and Tenedos near the Dardanelles, but this community diminished rapidly during the 20th century and only 200 elderly Greeks have remained there, less than 2%. In the 1950s, an estimated 98% of the island was Greek. In the last years the condition of the Greek community in these islands seems to be slightly improving.[59][60]

The Antiochian Greeks (Rum) living in Hatay are the descendants of the Ottoman Levant's and southeast Anatolia's Greek population and are part of the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch. They did not emigrate to Greece during the 1923 population exchange because at that time the Hatay province was under French control. The majority of the Antiochian Greeks moved to Syria and Lebanon at 1939, when Turkey took control of the Hatay region, however a small population remained at this area. After a process of Arabization and Turkification that took place in the 20th century, today almost their entirety speaks Arabic as a mother language. This has made them hard to distinguish from the Arab Christians and some argue that they have become largely homogenized. Their majority doesn't speak Greek at all, the younger generation speaks Turkish, and some have Turkish names now. Their population is about 18,000,[61] and they are faithful to the Patriarchate of Antiochia, although ironically it is now in Damascus. They reside largely in Antakya and/or the Hatay province, but a few are also in Adana province.

The Greek minority continues to encounter problems relating to education and property rights. A 1971 law nationalized religious high schools, and closed the Halki seminary on Istanbul's Heybeli Island which had trained Orthodox clergy since the 19th century. A later outrage was the vandalism of the Greek cemetery on Imbros on October 29, 2010. In this context, problems affecting the Greek minority on the islands of Imbros and Tenedos continue to be reported to the European Commission.[62]

In July 2011, Istanbul's Greek minority newspaper Apoyevmatini declared that it would shut down due to financial difficulties. The four-page Greek-language newspaper faced closure due to financial problems that had been further aggravated by the economic crisis in Greece, when Greek companies stopped publishing advertisements in the newspaper and the offices have already been shut down. This ignited campaign to help the newspaper. Among the supporters were students from Istanbul Bilgi University who subscribed to the newspaper. The campaign saved the paper from bankruptcy for the time being. Because the Greek community is close to extinction, the obituary notices and money from Greek foundations, as well as subscriptions overwhelmingly by Turkish people, are the only sources of income. This income covers only 40 percent of the newspaper expenditures.[63]

That event was followed in September 2011 by a government cash grant of 45,000 Turkish liras to the newspaper through the Turkish Press Advertisement Agency, as part of a wider support of minority newspapers.[64] The Turkish Press Advertisement Agency also declared intention to publish official government advertisements in minority newspapers including Greek papers Apoyevmatini and IHO.[65]

As of 2007, Turkish authorities have seized a total of 1,000 immovables of 81 Greek organizations as well as individuals of the Greek community.[66] On the other hand, Turkish courts provided legal legitimacy to unlawful practices by approving discriminatory laws and policies that violated fundamental rights they were responsible to protect.[67] As a result, foundations of the Greek communities started to file complaints after 1999 when Turkey's candidacy to the European Union was announced. Since 2007, decisions are being made in these cases; the first ruling was made in a case filed by the Phanar Greek Orthodox College Foundation, and the decision was that Turkey violated Article 1 of Protocol No. 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which secured property rights.[67]

A government decree published on 27 August 2011, paves the way to return assets that once belonged to Greek, Armenian, Assyrian, Kurd or Jewish trusts and makes provisions for the government to pay compensation for any confiscated property that has since been sold on, and in a move likely to thwart possible court rulings against the country by the European Court of Human Rights.[68][69]

Since the vast majority of properties confiscated from Greek trusts (and other minority trusts) have been sold to third parties, which as a result cannot be taken from their current owners and be returned, the Greek trusts will receive compensation from the government instead. Compensation for properties that were purchased or were sold to third parties will be decided on by the Finance Ministry. However, no independent body is involved in deciding on compensation, according to the regulations of the government decree of 27 August 2011. If the compensation were judged fairly and paid in full, the state would have to pay compensation worth many millions of Euros for a large number of properties. Another weakness of the government decree is that the state body with a direct interest in reducing the amount of compensation paid, which is the Finance Ministry, is the only body permitted to decide on the amount of compensation paid. The government decree also states that minority trusts must apply for restitution within 12 months of the publication of the government decree, which was issued on 1 October 2011, leaving less than 11 months for the applications to be prepared and submitted. After this deadline terminates on 27 August 2012, no applications can be submitted, in which the government aims to settle this issue permamenetly on a legally sound basis and prevent future legal difficulties involving the European Court of Human Rights.[70]

Demographics of Greeks in Istanbul

The Greek community of Istanbul numbered 67,550[13] people in 1955. However, after the Istanbul Pogrom orchestrated by Turkish authorities against the Greek community in that year, their number was dramatically reduced to only 48,000.[71] Today, the Greek community numbers about 2,000 people.[72]

| Year | People |

|---|---|

| 1897 | 236,000[73] |

| 1923 | 100,000[74] |

| 1955 | 48,000 |

| 1978 | 7,000[75] |

| 2006 | 2,500[15] |

| 2008 | 2,000[76] |

| 2014 | 2,200[77]–2,500[15] |

Notable people

- Patriarch Bartholomew I (1940): current patriarch of Constantinople. Born in Imbros as Dimitrios Arhondonis.

- Elia Kazan (1909-2003): American film director. Born Elias Kazancıoğlu in Istanbul

- Archbishop Elpidophoros of America (1967): current archbishop of America. Born in Bakırköy, Istanbul as Ioannis Lambriniadis.

- Patriarch Benedict I of Jerusalem (1892-1980): Patriarch of Jerusalem from 1957 to 1980. Born in Bursa as Vasileios Papadopoulos.

- Gilbert Biberian (1944-2023): guitarist and composer. Born in Istanbul from a Greek-Armenian family.

- Chrysanthos Mentis Bostantzoglou (1918-1995): cartoonist known as Bost, born in Istanbul.

- Thomas Cosmades (1924-2010): evangelical preacher and translators of the New Testament in Turkish. Born in Istanbul.

- Patriarch Demetrios I of Constantinople (1914-1991): patriarch of Constantinople from 1972 to 1991. Born in Istanbul.

- Antonis Diamantidis (1892-1945): musician. Born in Istanbul.

- Savas Dimopoulos (1952): particle physicist at Stanford University. Born in Istanbul.

- Aleksandros Hacopulos (1911-1980): politician, member of Grand National Assembly twice

- Violet Kostanda (1958): former volleyball player for Eczacıbaşı and the Turkish National Team. She was born in Istanbul from a Greek-Romani family. Her father Hristo played football for Beşiktaş.

- Minas Gekos (1959): basketball player and coach who played mainly in Greece. Born in Kurtuluş district of Istanbul.

- Patroklos Karantinos (1903-1976): modernism architect. Born in Istanbul.

- Kostas Kasapoglou (1935-2016): footballer player, once capped for the Turkish National Team. Born in Istanbul, he was known with his Turkishized name Koço Kasapoğlu.

- Konstantinos Spanoudis (1871-1941): politician, founder and first president of AEK Athens. Born in Istanbul, was forced to relocate to Athens.

- Antonis Kafetzopoulos (1951): actor. Born in Istanbul moved in Greece in 1964.

- Michael Giannatos (1941-2013): actor. Born in Istanbul moved in Greece in 1964

- Kostas Karipis (1880-1952): rhebetiko musician. Born in Istanbul.

- Nikos Kovis (1953): former Turkish football international. Born in Istanbul.

- Lefteris Antoniadis (1924-2012): Fenerbahçe legend and member of the Turkish national football team. He was born in Büyükada island near Istanbul and was known in Turkey as Lefter Küçükandonyadis.

- Ioanna Koutsouranti (1936): philosopher and Maltepe University Academic. Born in Istanbul from a Greek (Rum) family, she's known in Turkey as İoanna Kuçuradi.

- Sappho Leontias (1832-1900): writer, feminist and educationist. Born in Istanbul.

- Petros Markaris (1937): writer. Born in Istanbul.

- Kleanthis Maropoulos (1919-1991): Greek international footballer. Born in Istanbul, fled to Greece during the Greek-Turks population exchange when he was 3 years old.

See also

References

- "The Greek minority of Turkey". HRI.org. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. 2008-12-15. Archived from the original on 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- "Greeks Living in Turkey". ΜΕΓΑ ΡΕΥΜΑ. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- Türkyılmaz, Zeynep (2016-12-01). "Pontus'un kripto-hristiyan Rumları, İslam ve Hıristiyanlık arasında". REPAIR - Türkiye, Ermenistan ve Ermeni diasporası sivil toplumları arasında kültürlerarası diyalog projesi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- "saygi-ozturk/13-ilimiz-daha-gitti". www.sozcu.com.tr. 2018. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- Kaya, Nurcan (2015-11-24). "Teaching in and Studying Minority Languages in Turkey: A Brief Overview of Current Issues and Minority Schools". European Yearbook of Minority Issues Online. 12 (1): 315–338. doi:10.1163/9789004306134_013. ISSN 2211-6117.

Turkey is a nation–state built on remnants of the Ottoman Empire where non-Muslim minorities were guaranteed the right to set up educational institutions; however, since its establishment, it has officially recognised only Armenians, Greeks and Jews as minorities and guaranteed them the right to manage educational institutions as enshrined in the Treaty of Lausanne. [...] Private language teaching courses teach 'traditionally used languages', elective language courses have been introduced in public schools and universities are allowed to teach minority languages.

- Toktas, Sule (2006). "EU enlargement conditions and minority protection : a reflection on Turkey's non-Muslim minorities". East European quarterly. 40: 489–519. ISSN 0012-8449.

Turkey signed the Covenant on 15 August 2000 and ratified it on 23 September 2003. However, Turkey put a reservation on Article 27 of the Covenant which limited the scope of the right of ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religion or to use their own language. This reservation provides that this right will be implemented and applied in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Turkish Constitution and the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. This implies that Turkey grants educational right in minority languages only to the recognized minorities covered by the Lausanne who are the Armenians, Greeks and the Jews.

- Phillips, Thomas James (2020-12-16). "The (In-)Validity of Turkey's Reservation to Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 27 (1): 66–93. doi:10.1163/15718115-02701001. ISSN 1385-4879.

The fact that Turkish constitutional law takes an even more restrictive approach to minority rights than required under the Treaty of Lausanne was recognised by the UN Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) in its concluding observations on the combined fourth to sixth periodic reports of Turkey. The CERD noted that "the treaty of Lausanne does not explicitly prohibit the recognition of other groups as minorities" and that Turkey should consider recognising the minority status of other groups, such as Kurds. 50 In practice, this means that Turkey grants minority rights to "Greek, Armenian and Jewish minority communities while denying their possible impact for unrecognized minority groups (e.g. Kurds, Alevis, Arabs, Syriacs, Protestants, Roma etc.)".

- Bayır, Derya (2013). Minorities and nationalism in Turkish law. Cultural Diversity and Law. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 88–89, 203–204. ISBN 978-1-4094-7254-4.

- Toktas, Sule; Aras, Bulent (2009). "The EU and Minority Rights in Turkey". Political Science Quarterly. 124 (4): 697–720. ISSN 0032-3195.

- Köksal, Yonca (2006). "Minority Policies in Bulgaria and Turkey: The Struggle to Define a Nation". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 6 (4): 501–521. doi:10.1080/14683850601016390. ISSN 1468-3857.

- European Commission for Democracy through Law (2002). The Protection of National Minorities by Their Kin-State. Council of Europe. p. 142. ISBN 978-92-871-5082-0. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

In Turkey the Orthodox minority who remained in Istanbul, Imvros and Tenedos governed by the same provisions of the treaty of Lausanne was gradually shrunk from more than 200,000 in 1930 to less than 3,000 today.

- "Λέξεις – κλειδιά". www.demography-lab.prd.uth.gr. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- Kilic, Ecevit (2008-09-07). "Sermaye nasıl el değiştirdi?". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-12-25.

6-7 Eylül olaylarından önce İstanbul'da 135 bin Rum yaşıyordu. Sonrasında bu sayı 70 bine düştü. 1978'e gelindiğinde bu rakam 7 bindi.

- According to the Human Rights Watch the Greek population in Turkey is estimated at 2,500 in 2006. "From "Denying Human Rights and Ethnic Identity" series of Human Rights Watch" Archived 2006-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- "Against all odds: archaic Greek in a modern world | University of Cambridge". July 2010. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- Jason and the argot: land where Greek's ancient language survives, The Independent, Monday, 3 January 2011

- Özkan, Hakan (2013). "The Pontic Greek spoken by Muslims in the villages of Beşköy in the province of present-day Trabzon". Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies. 37 (1): 130–150. doi:10.1179/0307013112z.00000000023.

- Dawkins, R.M. 1916. Modern Greek in Asia Minor. A study of dialect of Silly, Cappadocia and Pharasa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nicolaos Mavrocordatos, Philotheou Parerga, J. Bouchard, 1989, p. 178: "Γένος μεν ημίν των άγαν Ελλήνων".

- Steven Runciman. The Great Church in Captivity. Cambridge University Press, 1988, page 197.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Greek history, The mercantile middle class". 2008 ed.

- Richard Clogg (20 June 2002). A Concise History of Greece. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-521-00479-4. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- Gelina Harlaftis (1996). A History of Greek-Owned Shipping: The Making of an International Tramp Fleet, 1830 to the Present Day. Routledge Chapman & Hall. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-415-00018-5. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

Constantinople contained the largest urban Greek population in the eastern Mediterranean and was the area's biggest commercial, banking and maritime centre.

- Gerwarth, Robert; Horne, John (2013). War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War. Oxford University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0199686056.

- Pentzopoulos, D. (2002). The Balkan Exchange of Minorities and Its Impact on Greece. Hurst. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-85065-702-6. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- Morris, Benny; Ze’evi, Dror (2019). The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey's Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924. Harvard University Press. p. 490. ISBN 978-0-674-24008-7.

- Jones, Adam, Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction, (Routledge, 2006), 154-155.

- Kinross, Lord (1960). Atatürk: The Rebirth of a Nation. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-297-82036-9.

- Shaw, Stanford Jay; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 342.

- Toynbee, p. 270.

- Rummel (Chapter 5)

- Akçam, Taner (2006). A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility. Macmillan. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-8050-7932-6.

- Shenk, Robert (2017). America's Black Sea Fleet: The U.S. Navy Amidst War and Revolution, 1919–1923. Naval Institute Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-61251-302-7.

- Toynbee (1922), pp. 312-313.

- Derya Bayir (2016). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. p. 123. ISBN 9781138278844.

- Vryonis, Speros (2005). The Mechanism of Catastrophe: The Turkish Pogrom of September 6–7, 1955, and the Destruction of the Greek Community of Istanbul. New York: Greekworks.com. ISBN 0-9747660-3-8.

- İnce, Başak (2012-04-26). Citizenship and identity in Turkey : from Atatürk's republic to the present day. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781780760261.

- Aslan, Senem (2009). "Incoherent State: The Controversy over Kurdish Naming in Turkey". European Journal of Turkish Studies (10). doi:10.4000/ejts.4142. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

the Surname Law was meant to foster a sense of Turkishness within society and prohibited surnames that were related to foreign ethnicities and nations

- Suny, Ronald Grigor; Goçek, Fatma Müge; Naimark, Norman M., eds. (2011-02-23). A question of genocide : Armenians, and Turks at the end of the Ottoman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195393743.

- Toktas, Sule (2005). "Citizenship and Minorities: A Historical Overview of Turkey's Jewish Minority". Journal of Historical Sociology. 18 (4): 394–429. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.2005.00262.x. S2CID 59138386. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Ağrı, Ülkü (2014). Pogrom in Istanbul, 6./7. September 1955. Berlin: Klaus Schwarz Verlag GmbH. p. 137. ISBN 9783879974399.

- Güven, Dilek (2005-09-06). "6–7 Eylül Olayları (1)". Radikal (in Turkish).

- Bahcheli, Tozun (2021). Greek-turkish Relations Since 1955. Westview Press. ISBN 9780429712258.

- TURKS EXPELLING ISTANBUL GREEKS; Community's Plight Worsens During Cyprus Crisis- The New York Times - AUG. 9, 1964

- Roudometof, Victor; Agadjanian, Alexander; Pankhurst, Jerry (2006). Eastern Orthodoxy in a Global Age: Tradition Faces the 21st Century. AltaMira Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0759105379.

- Greeks of Istanbul Unhappy With Both Ankara and Athens - The New York Times - April. 24, 1964

- RUM ORPHANAGE | World Monuments Fund

- "Prinkipo Orphanage". Institute of Strategical Thinking. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Greek Orthodox orphanage, Europe’s largest wooden building, awaits salvation off Istanbul

- Turkish mayor invites Greek-origin citizens back to Aegean island

- Arat, Zehra F. Kabasakal (April 2007). Human Rights in Turkey. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0812240009.

- Ramazan Kılınç (2019). Alien Citizens The State and Religious Minorities in Turkey and France. Cambridge University Press. p. 48. doi:10.1017/9781108692649. ISBN 9781108692649. S2CID 204426327.

- DENYING HUMAN RIGHTS AND ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE GREEKS OF TURKEY - A Helsinki Watch Report 1992

- Hirschon, Renée (2003). Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey. Berghahn Books. p. 120. ISBN 978-1571815620.

- Orthodox Patriarchate in Turkey Wins One Battle, Still Faces Struggle for Survival

- Population decline leaves Rums with Pyrrhic Victory

- Annual ritual at Sümela Monastery sparks debate

- "Η αναγέννηση της Ίμβρου: Ανθίζει ξανά το νησί του Πατριάρχη Βαρθολομαίου".

- "Η "Αναγέννηση" της ελληνικής κοινότητας της Ίμβρου -". Κανάλι Ένα 90,4 FM (in Greek). 2015-10-06. Retrieved 2021-03-23.

- "Christen in der islamischen Welt – Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte" (PDF). 2008. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- "Turkey 2007 Progress Report, Enlargement Strategy and Main Challenges 2007–2008" (PDF). Commission Stuff Working Document of International Affairs. p. 22.

- Hürriyet Daily News. 12 July 2011. "Turkey's sole Greek daily off the hook".

- Dardaki azınlık gazetelerine bayram gecesi yardımı... Sabah, 8 September 2011

- Minority Newspaper Meets with The Turkish Press Advertising Agency Greek Europe Reporter, 28 July 2011

- Kurban, Hatem, 2009: p. 48

- Kurban, Hatem, 2009: p. 33

- The Armenian Weekly, 28 August 2011 Turkey Decrees Partial Return of Confiscated Christian, Jewish Property (Update)

- Today's Zaman, 28 August 2011 Gov't gives go ahead for return of seized property to non-Muslim foundations

- Wwrn.org, 6 October 2011 TURKEY: What does Turkey's Restitution Decree mean?

- Karimova Nigar, Deverell Edward. "Minorities in Turkey" (PDF). The Swedish Institute of International Affairs. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-05-28. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- Gilson, George. "Destroying a minority: Turkey's attack on the Greeks Archived 2013-02-18 at archive.today", book review of (Vryonis 2005), Athens News, 24 June 2005.

- Erol, Merih (2015). Greek Orthodox Music in Ottoman Istanbul: Nation and Community in the Era of Reform. Indiana University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780253018427.

- Security Assistance Authorization: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Foreign Assistance, Subcommittee on Africa, and Subcommittee on Arms Control, Oceans, and International Environment of the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Ninety-fifth Congress, First Session, on S. 1160. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1977. p. 250.

- Kilic, Ecevit (2008-09-07). "Sermaye nasıl el değiştirdi?". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-12-25.

6-7 Eylül olaylarından önce İstanbul'da 135 bin Rum yaşıyordu. Sonrasında bu sayı 70 bine düştü. 1978'e gelindiğinde bu rakam 7 bindi.

- "Ecumenical Federation of Constantionopolitans - Report on the Minoirty Rights of the Greek-Orthodox Community of Istanbul September 2008" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-10-14.

- OSCE/ODIHR Human Dimension Implementation Meeting 2014 Rights of Persons Belonging to National Minorities - Warsaw 29 September 2014

Further reading

- Alexandrēs, Alexēs. "The Greek minority of Istanbul and Greek-Turkish relations, 1918-1974." Center for Asia Minor Studies, 1983.

- Grigoriadis, Ioannis N. (2021). "Between citizenship and the millet: the Greek minority in republican Turkey". Middle Eastern Studies. 57 (5): 741–757. doi:10.1080/00263206.2021.1894553. hdl:11693/77359. S2CID 233588979.

External links

- Istanbul Greek Minority Information Portal for present Greek Minority of Turkey in Greek, Turkish and English

- Athens protests latest desecration of Orthodox cemetery in Turkey

- Greeks of Istanbul (İstanbul Rumları) (Video)

- The Greeks of Turkey

- Greek - Turkish minorities

- Greeks Living in Turkey Today

- Turkey's Greek Community Grapples with adversity

- Turkey - Greeks