Griffith Park

Griffith Park is a large municipal park at the eastern end of the Santa Monica Mountains, in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. The park includes popular attractions such as the Los Angeles Zoo, the Autry Museum of the American West, the Griffith Observatory, and the Hollywood Sign. Due to its appearance in many films, the park is among the most famous municipal parks in North America.[1]

| Griffith Park | |

|---|---|

Ferndell bridge, Griffith Park | |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Los Feliz, Los Angeles, California |

| Coordinates | 34°8′N 118°18′W |

| Area | 4,310 acres (1,740 ha) |

| Created | 1896 |

| Operated by | Los Angeles Department of Recreation & Parks |

| Visitors | 10 million |

| Status | Open all year |

| Parking | See below |

| Website | www |

| Designated | January 27, 2009 |

| Reference no. | 942 |

It has been compared to Central Park in New York City and Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, but it is much larger, less tamed, and more rugged than either of those parks.[2] The Los Angeles Recreation and Parks Commission adopted the characterization of the park as an "urban wilderness" on January 8, 2014.[3][4] The park covers 4,310 acres (1,740 ha) of land, making it one of the largest urban parks in North America.[5] It is the second-largest city park in California, after Mission Trails Preserve in San Diego, and the 11th-largest municipally-owned park in the United States.[6]

History

Griffith donation

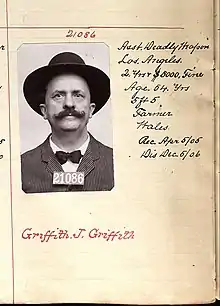

After successfully investing in mining, Griffith J. Griffith purchased Rancho Los Feliz (near the Los Angeles River) in 1882 and started an ostrich farm there. Although ostrich feathers were commonly used in making women's hats in the late 19th century, Griffith's purpose was primarily to lure residents of Los Angeles to his nearby property developments, which supposedly were haunted by the ghost of Antonio Feliz (a previous owner of the property). After the property rush peaked, Griffith donated 3,015 acres (1,220 ha) to the city of Los Angeles on December 16, 1896.[7][8]

Griffith was tried and convicted of shooting and severely wounding his wife in a 1903 incident.[9] When released from prison, he attempted to fund the construction of an amphitheater, observatory, planetarium, and a girls' camp and boys' camp in the park. As his reputation in the city was tainted by his crime, the city refused his money.[10]

.jpg.webp)

Griffith Park Aerodrome

In 1912, Griffith designated 100 acres (40 ha) of the park, at its northeast corner along the Los Angeles River, to be used to "do something to further aviation". The Griffith Park Aerodrome was the result. Aviation pioneers such as Glenn L. Martin and Silas Christofferson used it; afterwards the aerodrome was passed to the National Guard Air Service. Air operations continued on a 2,000-foot (600 m)-long runway until 1939, when it was closed, partly due to danger from interference with the approaches to Grand Central Airport across the river in Glendale, and because the City Planning commission complained that a military airport violated the terms of Griffith's deed.[11] The National Guard squadron moved to Van Nuys, and the aerodrome was demolished, though the rotating beacon and its tower remained for many years. From 1946 until the mid-1950s, Rodger Young Village occupied the area which had formerly been the Aerodrome. Today that site is occupied by the Los Angeles Zoo parking lot, the Gene Autry Western Heritage Museum, soccer fields, and the interchange between the Golden State Freeway and the Ventura Freeway.

Expansion

Griffith set up a trust fund for the improvements he envisioned, and after his death in 1919 the city began to build what Griffith had wanted. The amphitheater, called the Greek Theatre, was completed in 1930, and Griffith Observatory was finished in 1935. Subsequent to Griffith's original gift, further donations of land, city purchases, and the reversion of land from private to public have expanded the park to its present size.

In December, 1944 the Sherman Company donated 444 acres (180 ha) of Hollywoodland open space to Griffith Park. This large, passive, eco-sensitive property borders the Lake Hollywood reservoir (west), the former Hollywoodland sign (north), and Bronson Canyon (east) where it connects into the original Griffith donation. The Hollywoodland residential community is surrounded by this land.[12][13][14]

World War II

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Civilian Conservation Corps camp contained within Griffith Park was converted to a holding center for Japanese Americans arrested as "enemy aliens" before they were transferred to more permanent internment camps.[15] The Griffith Park Detention Camp opened almost immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, taking in 35 Japanese immigrants suspected of fifth column activity because they lived and worked near military installations. These men, mostly fishermen from nearby Terminal Island, were transferred to an Immigration and Naturalization Service detention station after a brief stay, but Issei internees arrested in the days and weeks following the outbreak of the war arrived soon after to take their place. Up to 550 Japanese Americans were confined in Griffith Park from 1941 to 1942, all subsequently transferred to Fort Lincoln, Fort Missoula and other DOJ camps.[16]

On July 14, 1942, the detention camp became a POW Processing Center for German, Italian and Japanese prisoners-of-war, operating until August 3, 1943, when the prisoners were transferred elsewhere. The camp was changed to the Army Western Corps Photographic Center and Camouflage Experimental Laboratory until the end of the war.[16]

Protest

On 17 March 1968, in Los Angeles, to protest entrapment and harassment by the Los Angeles Police Department, two drag queens known as "The Princess" and "The Duchess" held a St. Patrick's Day party at Griffith Park, a popular cruising spot and a frequent target of police activity. More than 200 gay men socialized through the day.[17]

Fires

Hired as part of a welfare project, 3,780 men were in the park clearing brush on October 3, 1933, when a fire broke out in the Mineral Wells area in the northern part of the current park. Many of the workers volunteered or were ordered to fight the fire. In all, 29 men were killed and 150 were injured. Professional firefighters arrived and limited the blaze to 47 acres (19 ha).[18]

On May 12, 1961, a wildfire on the south side of the park burned 814 acres (329 ha). It also destroyed eight homes and damaged nine more, chiefly in the Beachwood Canyon area.[19]

Another fire occurred c. 1971 in the Toyon Canyon area. Repelled by the ugliness of the devastated area, Amir Dialameh replanted a portion of it himself by hand. Over the course of more than 30 years he tended the garden he built there, with the help of occasional volunteers.[20] Amir's Garden is featured in Visiting... with Huell Howser episode 1306.[21]

On May 8, 2007, a major wildfire burned more than 817 acres (331 ha), destroying the bird sanctuary, Dante's View, and Captain's Roost, and forcing the evacuation of hundreds of people. The fire came right up to one of the largest playgrounds in Los Angeles, Shane's Inspiration, and the Los Angeles Zoo, and threatened the Griffith Observatory, but left such areas intact. Several local organizations, including SaveGriffithPark.org, have been working since then with local officials to restore the park in a way that would benefit all.[22] It was the third fire of the year.[23] The city announced a $50 million plan to stabilize the burned slopes. The trees along Canyon Drive were allowed to grow back naturally, having been re-seeded by bird droppings.[22]

Addition of Cahuenga Peak

One hundred acres (40 ha) around Cahuenga Peak were purchased with funds from a broad spectrum of donors, in addition to $1.7 million from the city,[24] and added to the park in July 2010[25] bringing the park's total acreage to 4,310 acres (1,740 ha).

Attractions

- Autry Museum of the American West

- Bronson Canyon

- Greek Theatre (Los Angeles)

- Griffith Observatory

- La Kretz Bridge

- Griffith Park & Southern Railroad

- Griffith Park Merry-Go-Round[26][27]

- Griffith Park Zoo - closed in 1966 and now used as a hiking and picnicking area

- Heritage tree: a pine tree in memory of Beatle George Harrison was planted in 2004 near the observatory. It died after a beetle infestation, and as of 2014, plans have been made to replace it.[28][29]

- The site of the Hollywood Sign on the southern side of Mount Lee is located on rough, steep terrain, and is encompassed by barriers to prevent unauthorized access. Local groups have campaigned to make tourist access to the sign difficult on grounds of safety, as the curving hillside roads in the area were not designed for so many cars and pedestrians.[30][31] The Hollywood Sign Trust convinced Google and other mapping services to stop providing directions to the location of the sign, instead directing visitors to two viewing platforms, Griffith Observatory and the Hollywood and Highland Center. Another, less remote area from which the sign can be viewed is Lake Hollywood Park on Canyon Lake Drive.[32]

- Los Angeles Live Steamers Railroad Museum

- Los Angeles Zoo

- Travel Town Museum

A statue of a standing bear, created in 1976 by Noack Foundry based on the design of German sculptor Renée Sintenis originally created in 1932, is located in the park. Its plaque reads "To the people of the United States of America in gratitude for their aid, friendship and protection. Presented to our sister city, Los Angeles by the people of free Berlin".[33] This is the same bear as that used to create the Golden Bear awards for the Berlin International Film Festival each year.[34]

Other activities

Much of the park comprises wild, rugged natural areas with hiking and equestrian trails, and this terrain separates the park into many areas or "pockets" of activities. Within the various areas are concessions, golf courses, picnic grounds, train rides, and tennis courts. In 2014, two baseball fields were proposed on the east side of Griffith Park that would remove 44 trees and replace four acres (1.6 ha) of picnic area, the largest picnic area in the park that is often used for large family gatherings, cultural fairs and festivals, reunions, and other special occasions. The plan may be altered to spare a sycamore that has been designated by the city as a "heritage tree", a living artifact of Los Angeles history.[35]

After its closure in 1966, the grounds of the Griffith Park Zoo were transformed into a recreation area. Some of the former animal enclosures were left in place, and picnic tables were installed.

The annual Bell-Jeff Invitational cross country race has been held in the park on the last Saturday in September since 1973.[36]

After 74 years in operation,[37] the Griffith Park Pony Rides closed on December 21, 2022.[38][39][40]

Hiking

.jpg.webp)

Griffith Park is a popular hiking area. Orientation maps are located at the entrance to the parking lot near Griffith Observatory. A service road leads from the observatory to numerous hiking routs on and around Mount Lee; however, the immediate area where the Hollywood Sign is located is closed to the public since the area is home to the main communication tower for the City of Los Angeles. Hiking up to Wisdom tree on Cahuenga Peak from the South-western slopes of Mount Lee is accessible.[41] Visitors are expected to comply with safety requirements, and must be prepared and equipped adequately.

Trails leading to the Hollywood Sign can be accessed from several official Griffith Park entrances. These include the Mt. Hollywood Trail, which can be accessed from the Griffith Observatory parking lot off Vermont Canyon Road or from Vermont Canyon Road just past the Greek Theater, the Bronson Canyon / Brush Canyon Trail (3200 Canyon Drive, Los Angeles, CA),[42] and a number of trailheads that begin near the Griffith Park Visitors Center off Crystal Springs Drive in the Los Feliz section of Los Angeles (free trail maps are available at the Visitors Center).[43] A once-popular trailhead originating at the top of Beachwood Drive was closed by court order in April 2017.[44]

Mount Lee

Mount Lee's hiking trails and fire roads are part of Griffith Park; as such it's easy to get lost and be redirected. Maps of the trails and the land around the hills should be studied before attempting to hike the area for the first time.[45]

Wildlife

An adult mountain lion, named P-22,[note 1] inhabited the park from 2012 to 2022.[46] An image of the cougar was captured on an automatic camera.[47][48][49] P-22 is likely not the first mountain lion to have taken up residence in Griffith Park, although the duration of his stay was remarkably long. A mountain lion's body was found in Griffith Park sometime in 1996 or 1997, after being hit by a vehicle. Another mountain lion was sighted several times in Griffith Park in 2004 and rangers found evidence (including deer remains) to support its presence there.[50]

An urban ecologist monitors wildlife within the park.[51] The ecologist has also been conducting a raptor study in the communities surrounding the park through volunteers since 2017.[52] Permanent signs on the Griffith Park Observatory deck warn of rattlesnakes in the surrounding area.[53]

Coyotes abound in Griffith Park and are generally active at night. Park visitors report frequent sightings during the day and have had their dogs attacked by coyotes.[54] Visitors are strongly discouraged from feeding Griffith Park coyotes including near "the base of Fern Canyon, where up to eight coyotes per day are present more or less continuously."[55]

The newly created habitat of a Miyawaki forest near the Bette Davis Picnic Area has attracted Western toads from the Los Angeles River.[56][57]

Geology

Much of the exposed rock in Griffith Park is marine or non-marine sedimentary rock of Neogene and Quaternary formations, including the Lower, Middle and Upper Topanga, as well as the Monterey and Fernando formations. Both inclined bedding and fossil-bearing strata are common. Also present is late Miocene intrusive rock, generally strongly weathered and easily cleaved, as well as some dikes and purple and gray andesitic extrusive rock bodies. Faulting as well as clear contacts between rock bodies are also common.[58]

Climate

| Climate data for Griffith Park, Los Angeles, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 91 (33) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

105 (41) |

109 (43) |

107 (42) |

113 (45) |

110 (43) |

112 (44) |

106 (41) |

100 (38) |

91 (33) |

113 (45) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 68 (20) |

69 (21) |

70 (21) |

75 (24) |

76 (24) |

82 (28) |

87 (31) |

88 (31) |

86 (30) |

81 (27) |

74 (23) |

68 (20) |

77 (25) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 45 (7) |

48 (9) |

50 (10) |

53 (12) |

55 (13) |

59 (15) |

62 (17) |

63 (17) |

61 (16) |

56 (13) |

48 (9) |

44 (7) |

54 (12) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 27 (−3) |

30 (−1) |

32 (0) |

37 (3) |

39 (4) |

39 (4) |

46 (8) |

46 (8) |

44 (7) |

40 (4) |

31 (−1) |

25 (−4) |

25 (−4) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.94 (100) |

4.46 (113) |

3.91 (99) |

1.01 (26) |

0.39 (9.9) |

0.09 (2.3) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.59 (15) |

1.36 (35) |

2.21 (56) |

18.47 (469) |

| Source: [59][60] | |||||||||||||

In popular culture

With its wide variety of scenes and close proximity to Hollywood and Burbank, various locations in the park have been used extensively in movies and television shows. Griffith Park was the busiest destination in Los Angeles for on-location filming in 2011, with 346 production days, according to a FilmL.A. survey. Projects included the TV series Criminal Minds and The Closer.[61]

Some sites within the park that have appeared in media include:

- Bronson Canyon, also called Bronson Caves, is a popular location for motion picture and television filming, especially of western and science fiction low-budget films, including Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). The site was also used as the location for the climactic scene in John Ford's classic western, The Searchers (1956). The scene includes Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) cornering his niece Debbie (Natalie Wood) in one of the caves with the apparent intent of killing her. The craggy site of an old quarry, a tunnel in this canyon was also used as the entrance to the Batcave in the 1960s Batman television series, and in numerous other shows. The natural "cave" walls are preserved by the many layers of paint used to make them look like rock.

- The Griffith Observatory, which sits atop the southern slope of Mount Hollywood, was featured prominently in the classic Rebel Without a Cause (1955). A bronze bust of the film's star James Dean is on the grounds just outside the dome. Other movies filmed here include The Terminator (1984), Disney's The Rocketeer (1991), Stephen Sommer's film Van Helsing (2004), Yes Man (2008), and La La Land (2016). The area of the park around the Observatory also appears as a location in the role-playing video game Vampire: The Masquerade Bloodlines (2004), which is set in Los Angeles. Griffith Park and Griffith Observatory are significant in the Star Trek: Voyager episode "Future's End" (originally aired November 6, 1996). The crew are thrown into the past and Griffith Observatory discovers Voyager. The tunnel was also used in the 1960s spy television series Mission: Impossible.

Views from Griffith Park

Views from Griffith Park - The Griffith Park Carousel, opened in 1929 was the carousel that inspired Disneyland. Walt sat on one of the benches around the Carousel, and while watching his kids dreamed up Disneyland. The Carousel is still open, and enriched with history.

- Films:

- D.W. Griffith (no relation to the eponym of Griffith Park) filmed the battle scenes for his epic The Birth of a Nation in the park in 1915, as Lillian Gish detailed in her memoirs, The Movies, Mr. Griffith, and Me.

- It was used for the road scenes in Sunset Boulevard (1950).

- The climactic scenes of War of the Colossal Beast (1958) were shot at Griffith Observatory.

- Flareup (1969), starring Raquel Welch.

- The Travel Town Museum's Griffith Park & Southern Railroad appears in the miniature train scene in The Parallax View (1974).

- The tunnel was used as the entrance to the NORAD complex in WarGames (1983).

- It was used as a location in the first two Back to the Future movies. In the first movie (released in 1985) it was used for Marty McFly's starting point when accelerating to 88 mph (142 km/h) in the film's climax, and in the second movie (released in 1989) it was used for the "River Road Tunnel" scene when Marty was trying to get the almanac back from Biff Tannen.

- The tunnel was also featured in a scene in Throw Momma from the Train (1987).

- The same tunnel was used as the entrance to Toontown in Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988).

- The park was also featured in the Robert Altman movie Short Cuts (1993).

- Roads within the park were used to stand in for Pacific coastal roads in The Majestic (2001).

- The area around the observatory is used extensively in La La Land (2016).

- Music:

- The park was the location for Adam Lambert's music video for his single, "If I Had You".

- Griffith Park was the location used in Ellie Goulding's music video "Guns and Horses".

- The silver Trans Am in the Simple Plan music video for Untitled (How Could This Happen to Me?) is seen driving out of the tunnel just before the head-on crash.

- Television - sampling of television shows filmed here includes:

- An episode of Remington Steele in which Laura Holt is trying to evade the police

- The Nickelodeon show Salute Your Shorts

- Scenes of Full House were taped here

Gallery

Welcome sign at Griffith Park's northeast entrance

Welcome sign at Griffith Park's northeast entrance Griffith Park (south side) with the Downtown LA skyline in the background

Griffith Park (south side) with the Downtown LA skyline in the background Sunset at Griffith Park, with a view of west Los Angeles.

Sunset at Griffith Park, with a view of west Los Angeles. Toyon Canyon Landfill, with San Fernando Valley to the north

Toyon Canyon Landfill, with San Fernando Valley to the north Pote Field, on Crystal Springs Drive

Pote Field, on Crystal Springs Drive Light Festival, 2009

Light Festival, 2009 Golfers at Wilson & Harding Course in Griffith Park (2013)

Golfers at Wilson & Harding Course in Griffith Park (2013) Railroad Museum

Railroad Museum View of Hollywood from Griffith Observatory, Dec. 2010

View of Hollywood from Griffith Observatory, Dec. 2010 Hikers climb the summit of Bee Rock in Griffith Park, Los Angeles.

Hikers climb the summit of Bee Rock in Griffith Park, Los Angeles. 1934 map with Griffith Park Aerodrome

1934 map with Griffith Park Aerodrome Lonesome Pine/Wisdom Tree on Burbank Peak

Lonesome Pine/Wisdom Tree on Burbank Peak

See also

- Hollywood Cricket Club

- Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monuments in Hollywood, Los Feliz and Griffith Park

- List of parks in Los Angeles

Similar large municipal parks elsewhere

- Daan Forest Park, Taipei, Taiwan (Republic of China)

- Royal National City Park, Stockholm, Sweden

- Stanley Park, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Notes

- "P" for puma, another name for mountain lion, and "22" as he is the 22nd of his species which has been tracked by National Park Service rangers.

References

- Schreiner, C. (2020). Discovering Griffith Park: A Local's Guide. Mountaineers Books. ISBN 978-1-68051-267-0. Retrieved September 30, 2020.

- Multiple sources:

- Hyperakt (March 10, 2018). "On the Grid: Griffith Park". On the Grid.

- "Best Family-Fun Activities At Griffith Park". June 28, 2017.

- "Griffith Observatory & Griffith Park Los Angeles". www.travelonline.com.

- "Griffith Park's Vision Plan". Friends of Griffith Park. Friends of Griffith Park. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- A Vision for Griffith Park (PDF) (Report). City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation and Parks. January 8, 2014.

- "Griffith Park".

- "The 150 Largest City Parks" (PDF). The Trust for Public Land.

- Griffith Park Archived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Gift To Los Angeles: Capitalist G. J. Griffith Donates as a Christmas Present a Magnificent Park Site". No. Volume 81, Number 17, Page 3. Los Angeles Herald. December 17, 1896. Retrieved November 17, 2015.

- "Death Summons Noble Woman", Los Angeles Sunday Times, November 13, 1904

- Morrison, Patt (May 3, 2022). "Griffith Park is named for a guy who shot his wife — and other true stories of L.A. parks". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- "Extension of Guard Airfield at Griffith Park Held Illegal". The Los Angeles Times. November 10, 1939. p. 38. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- Los Angeles City Archives, Piper Tech, Minutes of Meeting of Board of Playground and Recreation Commissioners, Monday, December 18, 1944

- Los Angeles City Ordinance 90638

- Quitclaim deed, Sherman Company, City of Los Angeles 2049 (Sherman Library and Gardens)

- Campa, Andrew J. (April 28, 2023). "Griffith Park's little-known history as a prison camp for Japanese, German, Italian immigrants". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- Masumoto, Marie. "Griffith Park" Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 13 Jun 2014.

- Witt, Lynn, Sherry Thomas and Eric Marcus (eds.) (1995). Out in All Directions: The Almanac of Gay and Lesbian America, p. 210. New York, Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-67237-8.

- "The Fire of '33", Glendale News-Press, October 1–4, 1993. Accessed May 8, 2007.

- A Holocaust Strikes the Hollywood Hills Archived August 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Otto Firgens, Los Angeles City Fire Department

- "Amir's Garden - Since 1971". Amirsgarden.org. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- "Amir's Garden- Visiting (1306) – Huell Howser Archives at Chapman University".

- "City to repair fire damage in Griffith Park" Ashraf Khalil, Los Angeles Times May 11, 2007

- "Fire Forces Griffith Park Evacuations" Archived May 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, KNBC.com, 11:27 pm PDT May 8, 2007

- "Hugh Hefner Saves The Hollywood Sign". Beverly Hills Courier. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- It's Official: Griffith Park Grows by More than 100 Acres with Addition of Cahuenga Peak Archived May 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. LAist (June 18, 2010). Retrieved on August 25, 2013.

- "Griffith Park". City of Los Angeles Department of Recreation & Parks. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Tremaine, Julie (October 14, 2020). "The story behind the California attraction that inspired Disneyland". SFGate. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Lewis, Randy (July 21, 2014). "George Harrison Memorial Tree killed ... by beetles; replanting due". Los Angeles Times.

- Lewis, Randy (February 20, 2015). "George Harrison tree -- killed by beetles -- to be replanted Feb. 25". Los Angeles Times.

- Bob Pool (October 8, 2013). "Discontent brewing under the Hollywood sign". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013.

- Bob Pool (October 9, 2013). "Hollywood sign tourists, sightseers annoy local residents". Los Angeles Times.

- Walker, Alissa (November 21, 2014). "Why People Keep Trying to Erase the Hollywood Sign From Google Maps". Gizmodo. Retrieved November 21, 2014.

- "Renee Sintenis, Standing Bear, Los Angeles". Public Art in Los Angeles and Southern California. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- François, Emmanuelle (March 2, 2018). "The woman behind the Bär". Exberliner. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- Sahagun, Louis (September 12, 2014). "Plans to add baseball fields to Griffith Park may draw legal challenge". Los Angeles Times.

- "Big Field Expected for Bell-Jeff Invitational". Los Angeles Times. September 30, 1989. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- "Griffith Park Pony Rides Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Scauzillo, Steve (December 22, 2022). "End of era: Children take last pony rides as city closes Griffith Park favorite". Daily News. Retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Scauzillo, Steve (January 8, 2023). "Historic structures at Griffith Park pony ride may hamper city's plans". Daily News. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the Griffith Park (PDF) (Report). Cultural Heritage Commission. October 30, 2008. CASE NO.: CHC-2008-2724-HCM.

- Lopez, Steve (November 10, 2022). "A hike to L.A.'s Wisdom Tree calms post-election nerves. And the view is perfect". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 12, 2022.

- "The Easy Hollywood Sign Hike (Directions & Parking)". HikingGuy.com. March 31, 2015. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- hollywoodsign.org

- "Griffith Park groups lose legal battle over pathway to see Hollywood sign". Los Angeles Times. March 22, 2018. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- "Griffith Park Trail Map" (PDF). www.laparks.org. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Steve Winter, Ghost Cats, National Geographic, December 2013.

- Keefe, Alexa (November 14, 2013) A Cougar Ready for His Closeup National Geographic

- "LA's Mountain Lion Is A Solitary Cat With A Knack For Travel". NPR. April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- Nijhuis, Michelle (April 20, 2015). "The Mountain Lions of Los Angeles". The New Yorker.

- Hymon, Steve; Sciaudone, Christiana (April 29, 2004). "A Mountain Lion Far From Home". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- Lovett, Ian (September 14, 2011). "Baying at the Bard, Appropriately and Otherwise". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- Kim, Dakota (March 2, 2023). "Go bird watching with an urban ecologist and learn about L.A.'s predators of the sky". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- Hicks, Reva (May 23, 2012). "Rattlesnake Warning: They're Shy, but Dangerous". NBC Southern California. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

the Southern Pacific rattlesnake [is] found in Griffith Park -- a place where humans, dogs and rattlesnakes share the trails.

- Wolfe, Chris; Habeshian, Sareen (January 26, 2022). "Actor Travis Van Winkle warns hikers after his dog was attacked by coyotes at Griffith Park". KTLA. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- Carey, Matthew (June 18, 2017). "LA park rangers warn visitors: Stop feeding the coyotes!". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- Buckley, Cara (August 24, 2023). "Tiny Forests With Big Benefits". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- Wagner, Tara Lynn (October 25, 2021). "In the face of a huge climate crisis, can micro forests be the answer?". spectrumnews1.com. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- Helman, Daniel (2012). "Public Geology at Griffith Park in Los Angeles: A Sample Teachers' Guide". Electronic Green Journal. 1 (33). doi:10.5070/G313310917. S2CID 129401303. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- "Griffith Park, CA Monthly Weather". Retrieved February 23, 2021.

- "Zipcode 90027". Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- "Top Film Locations for 2011". Los Angeles Times. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on December 15, 2011.

External links

- Los Angeles Department of Recreation & Parks: Griffith Park

- Griffith Park History

- Los Angeles Fire Department Historical Archive The Griffith Park Fire

- Griffith Park Aerodrome

- Griffith Observatory

- Photograph of the Griffith Park Fire of May 2007

- Updated crime report from Griffith Park

- Unveiling of original statue "Spirit of the C. C. C" by John Palo-Kangas in Griffith Park on the day President Roosevelt, Los Angeles, 1935, Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

- Image of Zoly Cubias and friend along Fern Dell stream in Griffith Park, Los Angeles, 1988. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.