Carcharhiniformes

Carcharhiniformes /kɑːrkəˈraɪnɪfɔːrmiːz/, the ground sharks, are the largest order of sharks, with over 270 species. They include a number of common types, such as catsharks, swellsharks, and the sandbar shark.

| Ground sharks Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| A finetooth shark, Carcharhinus isodon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Eugnathostomata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Superorder: | Galeomorphii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes Compagno, 1977 |

Members of this order are characterized by the presence of a nictitating membrane over the eye, two dorsal fins, an anal fin, and five gill slits.

The families in the order Carcharhiniformes are expected to be revised; recent DNA studies show that some of the conventional groups are not monophyletic.

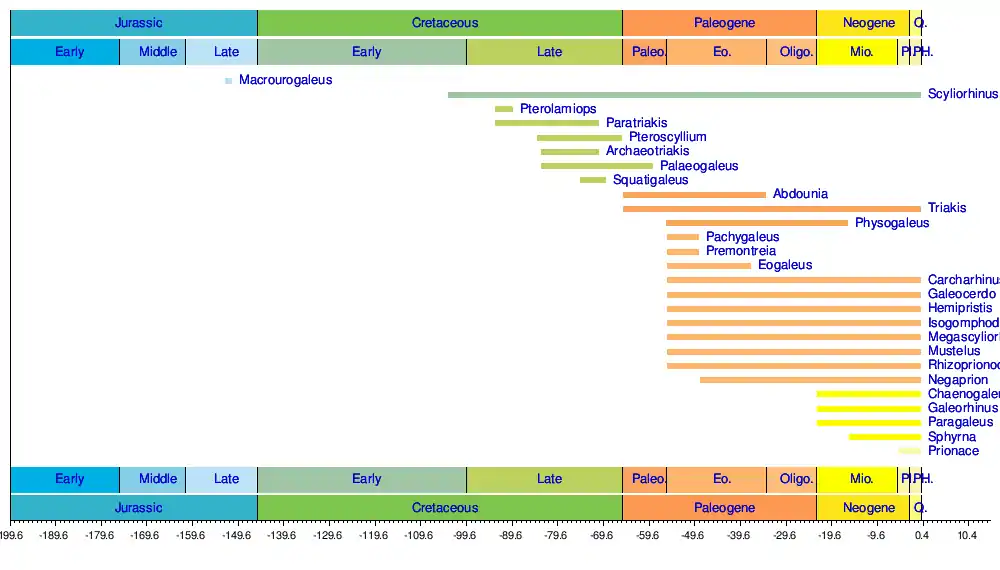

The oldest members of the order appeared during the Middle-Late Jurassic, which have teeth and body forms that are morphologically similar to living catsharks.[1] Carchariniformes first underwent major diversification during the Late Cretaceous, initially as mostly small-sized forms, before radiating into medium and large body sizes during the Cenozoic.[2][3]

Families

According to FishBase, the nine families of ground sharks are:[4]

- Carcharhinidae (requiem sharks)

- Galeocerdonidae (Tiger shark)

- Hemigaleidae (weasel sharks)

- Leptochariidae (barbeled houndshark)

- Proscylliidae (finback catsharks)

- Pseudotriakidae (false catsharks)

- Scyliorhinidae (catsharks)

- Sphyrnidae (hammerhead sharks)

- Triakidae (houndsharks)

| Family | Image | Common name | Genera | Species | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcharhinidae |  |

Requiem sharks | 11 | 59 | Requiem sharks are migratory, live-bearing sharks of warm seas (sometimes of brackish or fresh water) such as the blue shark, the bull shark, and the milk shark. The usual carcharhiniform characteristics include round eyes and pectoral fins that are completely behind five gill slits. Most species are viviparous, the young being born fully developed. They vary widely in size, from as small as 69 cm (2.26 ft) adult length in the Australian sharpnose shark, up to 4 m (13 ft) adult length in the oceanic whitetip shark.[5] Requiem sharks are responsible for a large proportion of attacks on humans. |

| Galeocerdonidae |  |

Tiger shark | 1 | 1 extant | A formerly diverse genus, only one species exists today. The tiger shark is the largest member of this order |

| Hemigaleidae | Weasel sharks | 4 | 8 | Weasel sharks are found from the eastern Atlantic Ocean to the continental Indo-Pacific in shallow coastal waters to a depth of 100 m (330 ft).[6] Most species are small, reaching no more than 1.4 m long (4.6 ft), though the snaggletooth shark (Hemipristis elongatus) may reach 2.4 m (7.9 ft). They have horizontally oval eyes, small spiracles, and precaudal pits. Two dorsal fins occur, with the base of the first placed well forward of the pelvic fins. The caudal fin has a strong ventral lobe and undulations on the dorsal lobe margin. They feed on a variety of small bony fishes and invertebrates; at least two species specialize on cephalopods. They are not known to have attacked people.[7] | |

| Leptochariidae |  |

Barbeled houndsharks | 1 | 1 | The only species of barbeled houndshark is Leptocharias smithii. It is a demersal species found in the coastal waters of the eastern Atlantic Ocean from Mauritania to Angola, at depths of 10–75 m (33–246 ft). It favours muddy habitats, particularly around river mouths. The barbeled houndshark is characterized by a very slender body, nasal barbels, long furrows at the corners of the mouth, and sexually dimorphic teeth. Its maximum known length is 82 cm (32 in). Likely strong-swimming and opportunistic, the barbeled houndshark has been known to ingest bony fishes, invertebrates, fish eggs, and even inedible objects. It is viviparous, with females bearing litters of seven young; the developing embryos are sustained by a unique globular placental structure. The IUCN has assessed the barbeled houndshark as near threatened, as heavy fishing pressure occurs throughout its range and it is used for meat and leather. |

| Proscylliidae |  |

Finback catsharks | 3 | 7 | |

| Pseudotriakidae | False catsharks | 3 | 5 | False catsharks are a small family containing false catsharks and gollumsharks. It contains the only ground shark species to exhibit intrauterine oophagy, in which developing fetuses are nourished by eggs produced by their mother.[8] | |

| Scyliorhinidae |  |

Catsharks | 17 | >150 | Catsharks are distinguished by their elongated, cat-like eyes and two small dorsal fins set far back. They usually have a patterned appearance, ranging from stripes to patches to spots. Most are fairly small, growing no longer than 80 cm (31 in); a few, such as the nursehound, can reach 1.6 m (5.2 ft) in length. They are found in temperate and tropical seas worldwide, ranging from shallow intertidal waters to depths of 2,000 m (6,600 ft) or more, depending on species.[9] They feed on invertebrates and smaller fish. Some species are aplacental viviparous, but most lay eggs in tough egg cases with curly tendrils at each end, known as mermaid's purses. The swell sharks of the genus Cephaloscyllium fill their stomachs with water or air when threatened, increasing their girth by a factor of two to three. Some catsharks are called dogfish. |

| Sphyrnidae |  |

Hammerhead sharks | 2 | 9 | Hammerhead sharks are named for the unusual and distinctive structure of their heads, which are flattened and laterally extended into a "hammer" shape called a cephalofoil. Many, not necessarily mutually exclusive, functions have been proposed for the cephalofoil, including sensory reception, manoeuvring, and prey manipulation. Hammerheads are found worldwide in warmer waters along coastlines and continental shelves. Unlike most sharks, hammerheads usually swim in schools during the day, becoming solitary hunters at night. |

| Triakidae |  |

Houndsharks | 9 | 40 | Houndsharks are distinguished by large spineless dorsal fins, an anal fin, and oval eyes with nictitating eyelids. They are small to medium in size, ranging from 37 to 220 cm (1.21 to 7.22 ft) in adult length. They are found throughout the world in warm and temperate waters, where they feed on fish and invertebrates on the sea bed and in midwater.[10] |

Timeline of genera

References

- Stumpf, Sebastian; Scheer, Udo; Kriwet, Jürgen (2019-03-04). "A new genus and species of extinct ground shark, †Diprosopovenator hilperti, gen. et sp. nov. (Carcharhiniformes, †Pseudoscyliorhinidae, fam. nov.), from the Upper Cretaceous of Germany". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (2): e1593185. Bibcode:2019JVPal..39E3185S. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1593185. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 155785248.

- Condamine, Fabien L.; Romieu, Jules; Guinot, Guillaume (2019-10-08). "Climate cooling and clade competition likely drove the decline of lamniform sharks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (41): 20584–20590. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11620584C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1902693116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6789557. PMID 31548392.

- Brée, Baptiste; Condamine, Fabien L.; Guinot, Guillaume (2022-12-19). "Combining palaeontological and neontological data shows a delayed diversification burst of carcharhiniform sharks likely mediated by environmental change". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 21906. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1221906B. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-26010-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9763247. PMID 36535995.

- Fish Identification: Ground sharks FishBase. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- Compagno, L.J.V. Family Carcharhinidae - Requiem sharks in Froese, R. and D. Pauly. Editors. 2010. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication, version (05/2010).

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2011). "Hemigaleidae" in FishBase. February 2011 version.

- Compagno, Leonard J. V. (1984) Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 92-5-101384-5.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Pseudotriakidae" in FishBase. December 2012 version.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Scyliorhinidae" in FishBase. January 2009 version.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Triakidae" in FishBase. January 2009 version.

Further reading

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2013) Fish Identification: Ground sharks in FishBase. March 2013 version.

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on 2012-05-10. Retrieved 2011-05-17.