Shark attack

A shark attack is an attack on a human by a shark. Every year, around 80 unprovoked attacks are reported worldwide.[1] Despite their rarity,[2][3][4][5] many people fear shark attacks after occasional serial attacks, such as the Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916, and horror fiction and films such as the Jaws series. Out of more than 500 shark species, only three of them are responsible for a double-digit number of fatal, unprovoked attacks on humans: the great white, tiger, and bull.[6] The oceanic whitetip has probably killed many more castaways, but these are not recorded in the statistics.[7]

| Shark attack | |

|---|---|

| |

| A sign warning about the presence of sharks off Salt Rock, South Africa |

Terminology

While the term "shark attack" is in common use for instances of humans being wounded by sharks, it has been suggested that this is based largely on the assumption that large predatory sharks (such as great white, bull, and tiger sharks) only seek out humans as prey. A 2013 review recommends that only in instances where a shark clearly predates on a human should the bite incident be termed an "attack," implying predation. Otherwise, it is more accurate to class bite incidents as "fatal bite incidents". Sightings do include physical interaction, encounters including physical interaction with harm, shark bites include major shark bite incidents, including those that require medical attention, and fatal shark bite incidents result in death. The study suggests that only in a case where an expert validates the predatory intent of a shark would it be appropriate to term a bite incident an attack.[8]

Statistics

| Region | Total attacks |

Fatal attacks |

Last fatality |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States[lower-alpha 1] | 1106 | 37 | 2021 |

| Australia | 647 | 261 | 2023 |

| Africa | 347 | 95 | 2023 |

| Asia | 129 | 48 | 2000 |

| Hawaii | 137[10] | 11[10] | 2019[11] |

| Pacific Islands / Oceania [lower-alpha 2] | 129 | 50 | 2023 |

| South America | 117 | 26 | 2018[12] |

| Antilles and Bahamas | 71 | 17 | 2022 |

| Middle America | 56 | 27 | 2011 |

| Europe | 52[13] | 27 | 1989 |

| New Zealand | 50 | 10 | 2021 |

| Réunion Island | 39 | 19 | 2019[14] |

| Unspecified / Open ocean | 21 | 7 | 1995 |

| Bermuda | 3 | 0 | — |

| Total: | 2900 | 633 | 2023 |

| Sources: Shark Attack Data Australia Australian Shark Attack File for unprovoked attacks in Australia International Shark Attack File for unprovoked attacks in all other regions Last Updated: 9 February 2023 | |||

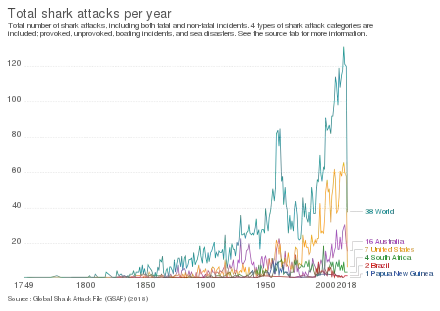

According to the International Shark Attack File (ISAF), between 1958 and 2016 there were 2,785 confirmed unprovoked shark attacks around the world, of which 439 were fatal.[15] Between 2001 and 2010, an average of 4.3 people a year died as a result of shark attacks.[3]

In 2000, there were 79 shark attacks reported worldwide, 11 of them fatal.[16] In 2005 and 2006, this number decreased to 61 and 62 respectively, while the number of fatalities dropped to only four per year.[16] The 2016 yearly total of 81 shark attacks worldwide was on par with the most recent five-year (2011–2015) average of 82 incidents annually.[17] By contrast, the 98 shark attacks in 2015, was the highest yearly total on record.[17] There were four fatalities worldwide in 2016, which is lower than the average of eight fatalities per year worldwide in the 2011–2015 period and six deaths per annum over the past decade.[17] In 2016 58% of attacks were on surfers.[17]

Despite these reports, however, the actual number of fatal shark attacks worldwide remains uncertain. For the majority of Third World coastal nations, there exists no method of reporting suspected shark attacks; therefore, losses and fatalities near-shore or at sea often remain unsolved or unpublicized.

Of these attacks, the majority occurred in the United States (53 in 2000, 40 in 2005, and 39 in 2006).[18] The New York Times reported in July 2008 that there had been only one fatal attack in the previous year.[19] On average, there are 16 shark attacks per year in the United States, with one fatality every two years.[20] According to the ISAF, the US states in which the most attacks have occurred are Florida, Hawaii, California, Texas and the Carolinas, though attacks have occurred in almost every coastal state.[21]

Australia has the highest number of fatal shark attacks in the world, with Western Australia recently becoming the deadliest place in the world for shark attacks[22] with total and fatal shark bites growing exponentially over the last 40 years.[23] Since 2000 there have been 17 fatal shark attacks along the West Australian coast[24] with divers now facing odds of one in 16,000 for a fatal shark bite.[23][25]

Other shark attack hotspots include Réunion Island,[26] Boa Viagem in Brazil, Makena Beach, Maui, Hawaii and Second Beach, Port St. Johns, South Africa.[27] South Africa has a high number of shark attacks along with a high fatality rate of 27 percent.[28]

As of 28 June 1992,[29] Recife in Brazil began officially registering shark attacks on its beaches (mainly on the beach of Boa Viagem). Over more than two decades, 64 victims were attacked, of which 26 died. The last deadly attack occurred on 10 July 2021.[30] The attacks were caused by the species bull shark and tiger shark.[31] The shark attacks in Recife have an unusually high fatality rate of about 37%. This is much higher than the worldwide shark attack fatality rate, which is currently about 16%, according to Florida State Museum of Natural History.[32] Several factors have contributed to the unusually high attack and fatality rates, including pollution from sewage runoff[33] and a (now closed) local slaughterhouse.[34]

The location with the most recorded shark attacks is New Smyrna Beach, Florida.[35] Developed nations such as the United States, Australia and, to some extent, South Africa, facilitate more thorough documentation of shark attacks on humans than developing coastal nations. The increased use of technology has enabled Australia and the United States to record more data than other nations, which could somewhat bias the results recorded. In addition to this, individuals and institutions in South Africa, the US and Australia keep a file which is regularly updated by an entire research team, the International Shark Attack File, and the Australian Shark Attack File.

The Florida Museum of Natural History compares these statistics with the much higher rate of deaths from other causes. For example, an average of more than 38 people die annually from lightning strikes in coastal states, while less than 1 person per year is killed by a shark in Florida.[36][37] In the United States, even considering only people who go to beaches, a person's chance of getting attacked by a shark is 1 in 11.5 million, and a person's chance of getting killed by a shark is less than 1 in 264.1 million.

However, in certain situations the risk of a shark attack is higher. For example, in the southwest of Western Australia the chances of a surfer being fatally bitten by a shark in winter or spring are 1 in 40,000 and for divers it is 1 in 16,000.[23][25] In comparison to the risk of a serious or fatal cycling accident, this represents three times the risk for a surfer and seven times the risk for a diver.[23]

Species involved in incidents

Only a few species of shark are dangerous to humans. Out of more than 480 shark species, only three are responsible for two-digit numbers of fatal unprovoked attacks on humans: the great white, tiger and bull;[6] however, the oceanic whitetip has probably killed many more castaways which have not been recorded in the statistics.[7] These sharks, being large, powerful predators, may sometimes attack and kill people, notwithstanding the fact that all have been filmed in open water by unprotected divers.[38][39] The 2010 French film Oceans shows footage of humans swimming next to sharks in the ocean. It is possible that the sharks are able to sense the presence of unnatural elements on or about the divers, such as polyurethane diving suits and air tanks, which may lead them to accept temporary outsiders as more of a curiosity than prey. Uncostumed humans, however, such as those surfboarding, light snorkeling or swimming, present a much greater area of exposed skin surface to sharks. In addition, the presence of even small traces of blood, recent minor abrasions, cuts, scrapes or bruises, may lead sharks to attack a human in their environment. Sharks seek out prey through electroreception, sensing the electric fields that are generated by all animals due to the activity of their nerves and muscles.

Most of the oceanic whitetip shark's attacks have not been recorded,[7] unlike the other three species mentioned above. Famed oceanographic researcher Jacques Cousteau described the oceanic whitetip as "the most dangerous of all sharks".[40]

Modern-day statistics show the oceanic whitetip shark as seldom being involved in unprovoked attacks. However, there have been a number of attacks involving this species, particularly during World War I and World War II. The oceanic whitetip lives in the open sea and rarely shows up near coasts, where most recorded incidents occur. During the world wars, many ship and aircraft disasters happened in the open ocean, and because of its former abundance, the oceanic whitetip was often the first species on site when such a disaster happened.

Infamous examples of oceanic whitetip attacks include the sinking of the Nova Scotia, a British steamship carrying 1,000 people that was torpedoed by a German submarine on 18 November 1942, near South Africa. Only 192 people survived, with many deaths attributed to the oceanic whitetip shark.[41] The same species is believed to have been responsible for many of the 600–800 or more casualties following the torpedoing of the USS Indianapolis on 30 July 1945.[42]

Black December refers to at least nine shark attacks on humans, causing six deaths, that occurred along the coast of KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, from 18 December 1957, to 5 April 1958.[43]

In addition to the four species responsible for a significant number of fatal attacks on humans, a number of other species have attacked humans without being provoked, and have on extremely rare occasions been responsible for a human death. This group includes the shortfin mako, hammerhead, Galapagos, grey reef, blacktip, lemon, silky shark and blue sharks.[6] These sharks are also large, powerful predators which can be provoked simply by being in the water at the wrong time and place, but they are normally considered less dangerous to humans than the previous group.

On the evening of 16 March 2009, a new addition was made to the list of sharks known to have attacked human beings. In a painful but not directly life-threatening incident, a long-distance swimmer crossing the Alenuihaha Channel between the islands of Hawai'i and Maui was attacked by a cookiecutter shark. The two bites were delivered about 15 seconds apart.[44]

- The three most commonly involved sharks

The great white shark is involved in the most fatal unprovoked attacks[45]

The great white shark is involved in the most fatal unprovoked attacks[45] The tiger shark ranks as the second most fatal in unprovoked attacks[45]

The tiger shark ranks as the second most fatal in unprovoked attacks[45] The bull shark ranks as the third most fatal in unprovoked attacks[45]

The bull shark ranks as the third most fatal in unprovoked attacks[45]

Types of attacks

Shark attack indices use different criteria to determine if an attack was "provoked" or "unprovoked." When considered from the shark's point of view, attacks on humans who are perceived as a threat to the shark or a competitor to its food source are all "provoked" attacks. Neither the International Shark Attack File (ISAF) nor the Global Shark Attack File (GSAF) accord casualties of air/sea disasters "provoked" or "unprovoked" status; these incidents are considered to be a separate category.[46][47] Postmortem scavenging of human remains (typically drowning victims) are also not accorded "provoked" or "unprovoked" status.[47][45] The GSAF categorizes scavenging bites on humans as "questionable incidents."[47] The most common criteria for determining "provoked" and "unprovoked" attacks are discussed below:

Provoked attack

Provoked attacks occur when a human touches, hooks, nets, or otherwise aggravates the animal. Incidents that occur outside of a shark's natural habitat, such as aquariums and research holding-pens, are considered provoked, as are all incidents involving captured sharks. Sometimes humans inadvertently provoke an attack, such as when a surfer accidentally hits a shark with a surf board.

Unprovoked attack

Unprovoked attacks are initiated by the shark—they occur in a shark's natural habitat on a live human and without human provocation.[46][47] There are three subcategories of unprovoked attack:

- Hit-and-run attack – usually non-fatal, the shark bites and then leaves; most victims do not see the shark. This is the most common type of attack and typically occurs in the surf zone or in murky water. Most hit-and-run attacks are believed to be the result of mistaken identity.[48]

- Sneak attack – the victim will not usually see the shark, and may sustain multiple deep bites. This kind of attack is predatory in nature and is often carried out with the intention of consuming the victim. It is extraordinarily rare for this to occur.

- Bump-and-bite attack – the shark circles and bumps the victim before biting. Great whites are known to do this on occasion, referred to as a "test bite", in which the great white is attempting to identify what is being bitten. Repeated bites, depending on the reaction of the victim (thrashing or panicking may lead the shark to believe the victim is prey), are not uncommon and can be severe or fatal. Bump-and-bite attacks are not believed to be the result of mistaken identity.[48]

An incident occurred in 2011 when a 3-meter long (~500 kg) great white shark jumped onto a 7-person research vessel off Seal Island, South Africa. The crew were undertaking a population study using sardines as bait and initially retreated to safety in the bow of the ship while the shark thrashed about, damaging equipment and fuel lines. To keep the shark alive while a rescue ship towed the research vessel to shore, the crew poured water over its gills and eventually used a pump for mechanical ventilation. The shark was ultimately lifted back into the water by crane and, after becoming disoriented and beaching itself in the harbor, was successfully towed out to sea, swimming away. The incident was judged to be an accident.[49]

Reasons for attacks

Large sharks species are apex predators in their environment,[50] and thus have little fear of any creature (other than orcas[51]) with which they cross paths. Like most sophisticated hunters, they are curious when they encounter something unusual in their territories. Lacking any limbs with sensitive digits such as hands or feet, the only way they can explore an object or organism is to bite it; these bites are known as test bites.[52] Generally, shark bites are exploratory, and the animal will swim away after one bite.[52] For example, exploratory bites on surfers are thought to be caused by the shark mistaking the surfer and surfboard for the shape of prey.[53] Nonetheless, a single bite can grievously injure a human if the animal involved is a powerful predator such as a great white or tiger shark.[54]

A shark will normally make one swift attack and then retreat to wait for the victim to die or weaken from shock and blood loss, before returning to feed. This protects the shark from injury from a wounded and aggressive target; however, it also allows humans time to get out of the water and survive.[55] Shark attacks may also occur due to territorial reasons or as dominance over another shark species, resulting in an attack.[56]

Sharks are equipped with sensory organs called the Ampullae of Lorenzini that detect the electricity generated by muscle movement.[57] The shark's electrical receptors, which pick up movement, detect signals like those emitted from fish wounded. An example, someone who is spearfishing, leading the shark to attack the person by mistake.[56] George H. Burgess, director of the International Shark Attack File, said the following regarding why people are attacked: "Attacks are basically an odds game based on how many hours you are in the water".[58]

Prevention

Reducing the risks

General advice to reduce risks of being bitten by a shark include:[59]

- Staying in groups as solitary individuals are more at risk of being bitten

- Only going in the water during the day

- Avoiding areas with a lot of fish or fishers

- Not wearing jewelry, which can create reflections like fish scale

- Avoiding splashs at the surface, because it makes sound which attracts sharks

Shark barrier

A shark barrier (otherwise known as a "shark-proof enclosure" or "beach enclosure") is a seabed-to-surface protective barrier that is placed around a beach to separate people from sharks. Shark barriers form a fully enclosed swimming area that prevents sharks from entering.[60] Shark barrier design has evolved from rudimentary fencing materials to netted structures held in place with buoys and anchors. Recent designs have used plastics to increase strength and versatility.

When deployed in sheltered areas shark barriers offer complete protection and are seen as a more environmentally friendly option as they largely avoid bycatch. However, barriers are not effective on surf beaches because they usually disintegrate in the swell and so are normally constructed only around sheltered areas such as harbour beaches.[61]

Shark nets

In Australia and South Africa shark nets are used to reduce the risk of shark attack. Since 1936 sharks nets have been utilised off Sydney beaches.[62] Shark nets are currently installed at beaches in New South Wales and Queensland; 83 beaches are meshed in Queensland compared with 51 in New South Wales.[62][63] Since 1952, nets have been installed at numerous beaches in South Africa by the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board.[64][65]

Shark nets do not offer complete protection but work on the principle of "fewer sharks, fewer attacks". They reduce occurrence via shark mortality. Reducing the local shark populations is believed to reduce the chance of an attack. Historical shark attack figures suggest that the use of shark nets and drumlines does markedly reduce the incidence of shark attack when implemented on a regular and consistent basis.[66][67]

The downside with shark nets is that they do result in bycatch, including threatened and endangered species.[64] Between September 2017 and April 2018, 403 animals were killed in the nets in New South Wales, including 10 critically endangered grey nurse sharks, 7 dolphins, 7 green sea turtles and 14 great white sharks.[68] Between 1950 and 2008, 352 tiger sharks and 577 great white sharks were killed in the nets in New South Wales—also during this period, a total of 15,135 marine animals were killed in the nets, including whales, turtles, rays, dolphins, and dugongs.[69] KwaZulu-Natal's net program, operated by the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board, has killed more than 33,000 sharks in a 30-year period—during the same 30-year period, 2,211 turtles, 8,448 rays, and 2,310 dolphins were killed in KwaZulu-Natal.[65]

Shark nets have been criticized by environmentalists, scientists, and conservationists; they say shark nets harm the marine ecosystem.[65][70][64] In particular, the current net program in New South Wales has been described as being "extremely destructive" to marine life.[71] Sharks are important to the ecosystem and killing them harms the ecosystem.[64][72][73]

Drum lines

A drum line is an unmanned aquatic trap used to lure and capture large sharks using baited hooks. They are typically deployed near popular swimming beaches with the intention of reducing the number of sharks in the vicinity and therefore the probability of shark attack. Drum lines were first deployed to protect users of the marine environment from sharks in Queensland, Australia in 1962. During this time, they were just as successful in reducing the frequency of shark attacks as the shark nets.[74][66][75] More recently, drumlines have also been used with great success in Recife, Brazil where the number of attacks has been shown to have reduced by 97% when the drumlines are deployed.[76] While shark nets and drum lines share the same purpose, drum lines are more effective at targeting the three sharks that are considered most dangerous to swimmers: the bull shark, tiger shark and great white shark.[77] SMART drumlines can also be utilised to move sharks, which greatly reduces mortality of sharks and bycatch to less than 2%.[78]

Drum lines result in bycatch; for example, in 2015 the following was said about Queensland's "shark control" program (which uses drum lines):

"[Data] reveals the ecological carnage of [Queensland's] shark control regime. In total, more than 8,000 marine species with some level of protection status have been caught by the Queensland Shark Control Program, including 719 loggerhead turtles, 442 manta rays and 33 critically endangered hawksbill turtles. More than 84,000 marine animals have been ensnared by drum-lines and shark nets since the program began in 1962 [...] Nearly 27,000 marine mammals have been snared. The state's shark control policy has captured over 5,000 turtles, 1,014 dolphins, nearly 700 dugongs and 120 whales."[79]

Drum lines have been criticized by environmentalists, conservationists and animal welfare activists—they say drum lines are unethical, non-scientific, and environmentally destructive; they also say drum lines harm the marine ecosystem.[80][81][82][83][73][84]

Other protection methods

Beach patrols and spotter aircraft are commonly used to protect popular swimming beaches. However aerial patrols have limited effectiveness in reducing shark attacks.[85][86] Other methods include shark tagging efforts and associated tracking and notification systems, capture and translocation of sharks to offshore waters, research into shark feeding and foraging behaviour,[87] public shark threat education programs and encouraging higher risk user groups (surfers, spear-fishers and divers) to use personal shark protection technology.[88]

Media impact

The Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916 killed four people in the first two weeks of July 1916 along the New Jersey shore and Matawan Creek in New Jersey. They are generally credited as the beginning of media attention on shark attacks in the United States of America.[89]

In 2010 nine Australian survivors of shark attacks banded together to promote a more positive view of sharks. The survivors made particular note of the role of the media in distorting the fear of sharks.[90] Films such as Jaws were the cause of large-scale hunting and killing of thousands of sharks.[91] Jaws had a significant impact on people and gave them an unrealistic view of sharks, causing them to fear them more than they probably should. The media has continued to exploit this fear over the years by sensationalizing attacks and portraying sharks as vicious man-eaters.[92] There are some television shows, such as the famous Shark Week, that are dedicated to the preservation of these animals.[93] They are able to prove through scientific studies that sharks are not interested in attacking humans and generally mistake humans as prey.

Notable shark attacks

- George Coulthard (1856–1883), Australian cricketer and Australian rules footballer

- Rodney Fox (b. 1940), Australian filmmaker and conservationist[94][95]

- Bethany Hamilton (b. 1990), American surfer

- Mathieu Schiller (1979–2011), French body-boarder

- Brook Watson (1735–1807), British soldier and Lord Mayor of London

- Mick Fanning (b. 1981), Australian Pro Surfer

- USS Indianapolis July–August 1945

- NOAAS Discoverer (R 102) March 23, 1994,

There are also reports of shark attack survivors being harassed and abused on social media, presumably by extreme environmentalists.[96]

See also

|

|

|

References

- "Yearly Worldwide Shark Attack Summary". International Shark Attack File. Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

The 2016 yearly total of 81 unprovoked attacks was on par with our most recent five-year (2011–2015) average of 82 incidents & 11 deaths annually.

- "ASU shark scientist: Fatal shark attacks 'extremely rare'". ASU News. 6 August 2020.

- "Shark attacks are rare – and related deaths even rarer". The Guardian. 17 August 2011.

- Plumer, Brad (8 July 2014). "How common are shark attacks, really?". Vox.

- "Chart: The animals that are most likely to kill you this summer – The Washington Post". The Washington Post.

- ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark

- Edmonds, Molly (5 June 2008). "HowStuffWorks "Dangerous Shark 4: Oceanic Whitetip Shark"". Animals.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Pepin-Neff, Christopher; Hueter, Robert (23 January 2013). "Science, policy, and the public discourse of shark "attack": a proposal for reclassifying human–shark interactions". Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences. 3 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1007/s13412-013-0107-2.

- "Total shark attacks per year". Our World in Data.

- "Incidents List". Government of Hawaii. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Lam, Kristin (27 May 2019). The Associated Press (ed.). "California man, 65, swimming off Maui killed in Hawaii's first fatal shark attack since 2015". USA Today. Gannett. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "A Teen Died After Losing His Leg and Penis in a Horrific Shark Attack". 4 June 2018.

- "Confirmed Unprovoked Shark Attacks (1847–Present). Europe". Florida Museum of Natural History. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- "Un surfeur tué après une attaque de requin à La Réunion". BFMTV. 9 May 2019.

- "World's Confirmed Unprovoked Shark Attacks". International Shark Attack File. 25 August 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- "ISAF Statistics for the Top Ten Worldwide Locations with the Highest Shark Attack Activity (1999–2009)". Florida Museum of Natural History Flmnh.ufl.edu. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "ISAF 2016 Worldwide Shark Attack Summary". Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "ISAF Statistics for the USA Locations with the Highest Shark Attack Activity Since 1999". Flmnh.ufl.edu. 3 May 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Tierney, John (29 July 2008). "10 Things to Scratch From Your Worry List". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 September 2010.

- "Shark Facts: Attack Stats, Record Swims, More". News.nationalgeographic.com. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Map of United States (incl. Hawaii) Confirmed Unprovoked Shark Attacks". Flmnh.ufl.edu. 26 August 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "WA 'deadiest' for shark attacks – The West Australian". Au.news.yahoo.com. 1 April 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Sprivulis, P (2014). "Western Australian Coastal Shark Bites: A risk assessment". Australasian Medical Journal. 7 (2): 137–42. doi:10.4066/AMJ.2014.2008. PMC 3941575. PMID 24611078.

- "Timeline of shark attacks along the Western Australian coast". WA Today. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- "Shark attacks and whale migration in Western Australia". Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Ballas, Richard; Saetta, Ghislain; Peuchot, Charline; Elkienbaum, Philippe; Poinsot, Emmanuelle (2017). "Clinical features of 27 shark attack cases on La Réunion Island (PDF Download Available)". Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 82 (5): 952–955. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000001399. PMID 28248805. S2CID 21996541. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- "The World's 10 Deadliest Shark Attack Beaches". The Inertia. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- "Map of World's Confirmed Unprovoked Shark Attacks". Flmnh.ufl.edu. 6 January 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "Shark Attack Data Brazil". Shark Attack Data. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "Maioria dos incidentes com tubarão em Pernambuco ocorreu no mês de julho;". Folha de Pernambuco. 27 July 2021. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- "Ataques de tubarão em Recife – Conheça a verdade e as causas desse fenômeno". Visitar Recife. 27 November 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "The beautiful Brazilian beaches plagued by shark attacks". BBC. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "The beautiful Brazilian beaches plagued by shark attacks". BBC. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "SHARK WEEK! FLORIDA EXPERT WADES INTO SCARY BRAZIL WATERS". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. 29 July 2006. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Regenold, Stephen (21 April 2008). "North America's top shark-attack beaches". USA Today. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "The Relative Risk of Shark Attacks to Humans". Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. A Comparison with the Number of Lightning Fatalities in Coastal United States: 1959–2006

- "Hawaiian newspaper article". Honoluluadvertiser.com. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- The 1992 Cageless shark-diving expedition by Ron and Valerie Taylor.

- Cousteau, Jacques-Yves & Cousteau, Philippe (1970). The Shark: Splendid Savage of the Sea. Doubleday & Company, Inc.

- Bass, A.J., J.D. D'Aubrey & N. Kistnasamy. 1973. "Sharks of the east coast of southern Africa. 1. The genus Carcharhinus (Carcharhinidae)." Invest. Rep. Oceanogr. Res. Inst., Durban, no. 33, 168 pp.

- Martin, R. Aidan. "Elasmo Research". ReefQuest. Retrieved 6 February 2006.

- "South Africa Rethinks Use of Shark Nets". Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- University of Florida News New study documents first cookiecutter shark attack on a live human

- "ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark". Global Shark Attack File. 9 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- Burgess, George H. "ISAF 2011 Worldwide Shark Attack Summary". Global Shark Attack File. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- "Incident Log". Global Shark Attack File. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Burgess, George H. "How, When, & Where Sharks Attack". International Shark Attack File. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Rice, Xan (19 July 2011). "Great white shark jumps from sea into research boat". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 July 2011.

Marine researchers in South Africa had a narrow escape after a three-metre-long great white shark breached the surface of the sea and leaped into their boat, becoming trapped on deck for more than an hour. [...] Enrico Gennari, an expert on great white sharks, [...] said it was almost certainly an accident rather than an attack on the boat.

- "Apex Predators Program". Na.nefsc.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Turner, Pamela S. (October–November 2004). "Showdown at Sea: What happens when great white sharks go fin-to-fin with killer whales?". National Wildlife. 42 (6). Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- "What To Expect on Your Great White Shark Diving Tour". Romow.com. 7 August 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Grabianowski, Ed (10 August 2005). "HowStuffWorks "How Shark Attacks Work"". Adventure.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Grabianowski, Ed (10 August 2005). "HowStuffWorks "Shark Attack Damage"". Adventure.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "Great White Shark". Extremescience.com. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- Grabianowski, Ed (10 August 2005). "HowStuffWorks "Shark Sensory System"". Adventure.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "Ampullae of Lorenzini". Marinebiodiversity.ca. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "Shark attacks at record high". BBC News. 9 February 2001. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- "Advice to Swimmers". Florida Museum. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- Meerman, Ruben (16 January 2009). "Shark nets". ABC Science. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Fact File: Protecting people from shark attacks". ABC News. 5 January 2015.

- Nick, Carroll. "Nick Carroll On-Beyond the Panic, The Facts about Shark Nets". Coastal Watch. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- "Beyond the panic: the facts about shark nets". Australian Community Media – Fairfax Media. 8 November 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- "Shark Attacks and the Surfer's Dilemma: Cull or Conserve?". 21 August 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- http://www.sharkangels.org/index.php/media/news/157-shark-nets Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine Shark Nets. Sharkangels.org. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Curtis; et al. (2012). "Responding to the risk of white shark attack: updated statistics, prevention, control, methods and recommendation. Chapter 29 In: M. L. Domeier (ed). Global Perspectives on the Biology and Life History of the White Shark". CRC Press. Boca Raton, FL. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Can governments protect people from killer sharks?". ABC News. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- "Sydney shark nets set to stay despite drumline success | Swellnet Dispatch | Swellnet". Swellnet.com. Sydney shark nets set to stay despite drumline success. Bruce Mackenzie. 4 August 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Shark culling · Save our Sharks · Australian Marine Conservation Society". Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Marineconservation.org.au. Shark culling (archived). Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "NSW govt won't back down on shark nets | SBS News". NSW govt won't back down on shark nets. Sbs.com.au. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- "Here's What You Need To Know About Australia's SMART Drum Lines Being Used To Prevent Shark Attacks". BuzzFeed.

Here's What You Need To Know About Australia's SMART Drum Lines Being Used To Prevent Shark Attacks. Elfy Scott. 5 July 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2018. - "The Importance of Sharks | Oceana Europe". Eu.oceana.org. The Importance of Sharks in the Ecosystem. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Alana Schetzer (8 May 2017). "Sharks: How a cull could ruin an ecosystem | Pursuit by The University of Melbourne". 8 May 2017. "Sharks: How a cull could ruin an ecosystem". Science Matters. University of Melbourne – via Pursuit. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- A Report on the Queensland Shark Safety Program (PDF), Queensland Government, Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries, March 2006, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2014, retrieved 6 January 2017

- Dudley, S.F.J. (1997). "A comparison of the shark control programs of New South Wales and Queensland (Australia) and KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa)". Ocean Coast Manag. 34 (34): 1–27. doi:10.1016/S0964-5691(96)00061-0.

- Hazin, F. H. V.; Afonso, A. S. (1 August 2014). "A green strategy for shark attack mitigation off Recife, Brazil". Animal Conservation. 17 (4): 287–296. doi:10.1111/acv.12096. hdl:10400.1/11160. S2CID 86034169.

- Dudley, Sheldon F.J.; Haestier, R.C.; Cox, K.R.; Murray, M. (January 1998). "Shark control: Experimental fishing with baited drumlines". Marine and Freshwater Research. 49 (7): 653. doi:10.1071/MF98026.

- "NSW North Coast SMART drumline data". NSW Government: Department of Primary Industries. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- "Queensland's Shark Control Program Has Snagged 84,000 Animals, Latest news". Action for Dolphins. Queensland's Shark Control Program Has Snagged 84,000 Animals. Thom Mitchell. 20 November 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "Sharks – Marine Science Australia". Sharks – Marine Science Australia. Ausmarinescience.com. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- http://www.seashepherd.org.au/apex-harmony/overview/queensland.html Archived 23 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine Queensland – Overview. Seashepherd.org.au. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Calla Wahlquist (12 February 2015). "Western Australia's 'serious threat' shark policy condemned by Senate | Western Australia". The Guardian. 12 February 2015. "Western Australia's 'serious threat' shark policy condemned by Senate". Retrieved 18 September 2018

- Carl Meyer (11 December 2013). "Western Australia's shark culls lack bite (and science)". "Western Australia's shark culls lack bite (and science)". Theconversation.com. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Chloe Hubbard (30 April 2017). "No Shark Cull: Why Some Surfers Don't Want to Kill Great Whites Despite Lethal Attacks". NBC News. "No Shark Cull: Why Some Surfers Don't Want to Kill Great Whites Despite Lethal Attacks". NBC News. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Green, M.; Ganassin, C.; Reid, D. D. "Report into the NSW Shark Meshing (Bather Protection) Program" (PDF). State of New South Wales through NSW Department of Primary Industries. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- Robbins, William D.; et al. (2014). "Experimental evaluation of shark detection rates by aerial observers". PLOS One. 9 (2): e83456. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...983456R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083456. PMC 3911894. PMID 24498258.

- "Thousands protest over shark cull in Australia", The Telegraph, UK, 1 February 2014, archived from the original on 18 November 2021, retrieved 5 January 2017

- Open letter to WA Government re: Proposal to use drum lines for shark population control and targeting of sharks entering protected beach (PDF), Support Our Sharks, 2013, retrieved 5 January 2017

- McCall, Matt (2 July 2015). "2 Weeks, 4 Deaths, and the Beginning of America's Fear of Sharks". National Geographic News. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- attack survivors unite to save sharks, Australian Geographic, 14 September 2010

- Choi, Charles Q. "How 'Jaws' Forever Changed Our View of Great White Sharks". Web. Live Science. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Beryl, Francis (2011). "Before and after Jaws: Changing representations of shark attacks". researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- "Shark Week : Discovery Channel". Dsc.discovery.com. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- "Dangerous shores for Jaws". The Olive Press. Luke Stewart Media SL. 28 March 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- McGowan, Cliodhna (1 February 2007). "ISDHF looks to permanent home". Caycom Pass. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- Smith, Emily (29 August 2021). "Shark attack survivor and drumline contractor say conservation group supporters harass them". ABC News. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

External links

- International Shark Attack File

- Global Shark Attack File — Open database

- Tracking Sharks — Current Shark Attack Statistics

- Shark Attack Survivors — Shark attack education and prevention

Notes

- Excluding Hawaii

- Excluding Hawaii, Australia and New Zealand