Guadalajara

Guadalajara (/ˌɡwɑːdələˈhɑːrə/ GWAH-də-lə-HAR-ə,[5] Spanish: [ɡwaðalaˈxaɾa] ⓘ) is a metropolis in western Mexico and the capital of the state of Jalisco. According to the 2020 census, the city has a population of 1,385,629 people, making it the 7th most populous city in Mexico, while the Guadalajara metropolitan area has a population of 5,268,642 people,[6][7] making it the third-largest metropolitan area in the country and the twentieth largest metropolitan area in the Americas[8] Guadalajara has the second-highest population density in Mexico, with over 10,361 people per square kilometer.[9] Within Mexico, Guadalajara is a center of business, arts and culture, technology and tourism; as well as the economic center of the Bajío region.[10][11][12] It usually ranks among the 100 most productive and globally competitive cities in the world.[13] It is home to numerous landmarks, including Guadalajara Cathedral, the Teatro Degollado, the Templo Expiatorio, the UNESCO World Heritage site Hospicio Cabañas, and the San Juan de Dios Market—the largest indoor market in Latin America.[14][15]

Guadalajara | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

| Nicknames: Pearl of the West The City of Roses Tapatian pearl | |

.png.webp) | |

Guadalajara Location of Guadalajara within Jalisco  Guadalajara Guadalajara (Mexico)  Guadalajara Guadalajara (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 20°40′36″N 103°20′51″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Region | Centro |

| Municipality | Guadalajara |

| Foundation | February 14, 1542 |

| Founded by | Cristóbal de Oñate |

| Named for | Guadalajara, Spain |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Pablo Lemus Navarro[1] (MC) |

| Area | |

| • City and municipality | 151 km2 (58 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,734 km2 (1,056 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,566 m (5,138 ft) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City and municipality | 1,385,629 [2] |

| • Rank | 13th in North America 7th in Mexico |

| • Density | 1,491.57/km2 (3,863.1/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 5,286,642 (3rd)[2] |

| • Metro density | 1,897/km2 (4,910/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Tapatío Guadalajarense (archaic)[3][4] |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Climate | Cwa |

| Website | www |

A settlement was established in the region of Guadalajara in early 1532 by Cristóbal de Oñate, a Basque conquistador in the expedition of Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán. The settlement was renamed and [16]moved several times before assuming the name Guadalajara after the birthplace of Guzmán and in 1542, ending up at its current location in the Atemajac Valley. On November 8, 1539 the Emperor Charles V had granted a coat of arms and the title of city to the new town and established it as the capital of the Kingdom of Nueva Galicia, part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. After 1572, the Royal Audiencia of Guadalajara, previously subordinate to Mexico City, became the only authority in New Spain with autonomy over Nueva Galicia, owing to rapidly growing wealth in the kingdom following the discovery of silver. By the 18th century, Guadalajara had taken its place as Mexico's second largest city, following mass colonial migrations in the 1720s and 1760s. During the Mexican War of Independence, independence leader Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla established Mexico's first revolutionary government in Guadalajara in 1810. The city flourished during the Porfiriato, with the advent of the industrial revolution, but its growth was hampered significantly during the Mexican Revolution. In 1929, the Cristero War ended within the confines of the city, when President Plutarco Elías Calles proclaimed the Grito de Guadalajara. The city saw continuous growth throughout the rest of the 20th century, attaining a metro population of 1 million in the 1960s and surpassing 3 million in the 1990s.

Guadalajara is a Gamma+ global city,[17] and one of Mexico's most important cultural centers. It is home to numerous mainstays of Mexican culture, including Mariachi, Tequila, and Birria and hosts numerous notable events, including the Guadalajara International Film Festival, one of the most important film festival in Latin America, and the Guadalajara International Book Fair, the largest book fair in the Americas. The city was the American Capital of Culture in 2005 and has hosted numerous global events, including the 1970 FIFA World Cup, the 1986 FIFA World Cup, the 1st Ibero-American Summit in 1991, and the 2011 Pan American Games. The city is home to numerous universities and research institutions, including the University of Guadalajara and the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara, two of the highest-ranked universities in Mexico.[18][19]

Etymology

The conquistador Cristóbal de Oñate named the city in honor of the conqueror of western Mexico, Nuño de Guzmán, who was born in Guadalajara, Spain. The name comes from the Arabic وادي الحجارة (wādī al-ḥajārah), which means 'Valley of the Stone', or 'Fortress Valley'.

History

Pre-Hispanic era

Unlike the surrounding areas, the central Atemajac Valley, where Guadalajara is located, contained no human settlements. To the east of the Atemajac Valley were the Tonallan and Tetlán peoples. At the extremes were the Zapopan, Atemajac, Zoquipan, Tesistan, Coyula, and Huentitán.

The historic city center encompasses what was once four population centers, as the villages of the Mezquitán, Analco, and Mexicaltzingo were annexed to the Atemajac site in 1669.[20]

Foundation

.jpg.webp)

Guadalajara was originally founded at three other sites before moving to its current location. The first colonial settlement in 1532 was in Mesa del Cerro, now known as Nochistlán, Zacatecas. This site was colonized by Cristóbal de Oñate as commissioned by Nuño de Guzmán, with the purpose of securing recent conquests and "defending" them from the "still-hostile natives". This colonized settlement did not last long due to its lack of usable water sources. In 1533 it was moved to a site near Tonalá. Four years later, Guzmán ordered that the village be moved to Tlacotán. During this time, the Spanish king Charles I granted the city the coat of arms which it retains to this day.[20]

During the Mixtón War, the Caxcan, Portecuex, and Zacateco peoples, fought back against colonizers under the command of Tenamaxtli.[20] The war was initiated in response to the heinous treatment of indigenous peoples by Nuño de Guzmán, in particular the enslavement of captured natives. After multiple defeats, Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza took control of the Spanish campaign to suppress the revolt. The conflict ended after Mendoza made concessions such as freeing enslaved indigenous peoples and granting amnesty.[21] The village of Guadalajara barely survived the war, and the villagers attributed their survival to the Archangel Michael, who remains the patron of the city to this day.

After the war, the city was moved once again—this time to a more defensible location. This final relocation would prove permanent. In 1542, records indicate that 126 people were living in Guadalajara. That same year, it was granted cityhood by the king of Spain. Guadalajara was officially founded on February 14, 1542, in the Atemajac Valley. The colonized settlement was named for Nuño de Guzmán's Spanish hometown.[20]

In 1559, royal and bishopric offices for the province of Nueva Galicia were moved from Compostela to Guadalajara and, in 1560, Guadalajara became the province's new capital. Construction of the cathedral began in 1563. In 1575, religious orders such as the Augustinians and Dominicans arrived, eventually making the city a center for evangelization efforts.[20]

While capital of the Kingdom of Nueva Galicia, the city's inhabitants achieved a high standard of living, due to flourishing industry, agriculture, commerce, mining, and trade. The Guadalajara of the sixteenth century was a rather small and often overlooked community. It was mainly frequented by traveling merchants. Several epidemics drastically reduced the city's indigenous population, leading to the construction of its first hospital in 1557.

Guadalajara's economy during the 18th century was based on agriculture and the production of non-durable goods such as textiles, shoes and food products.[22]

Despite epidemics, plagues, and earthquakes, Guadalajara would become one of the most important population centers in New Spain. The city's heyday attracted numerous architects, philosophers, lawyers, scientists, poets, writers, and speakers; Francisco Xavier Clavijero and Matías de la Mota Padilla were among the most prominent. In 1771, Bishop Fray Antonio Alcalde arrived in the city and founded the Civil Hospital and the University of Guadalajara. In 1791, the University of Guadalajara was established. The dedication was held in 1792 at the site of the old Santo Tomas College. While the institution was founded during the 18th century, it would not be fully developed until the 20th century, starting in 1925. In 1794, the Hospital Real de San Miguel de Belén, or simply the Hospital de Belén, was opened.[20]

In 1793, Mariano Valdés Téllez ran the city's first printing press, whose first publication was a funeral eulogy for Fray Antonio Alcalde.

Independence

Guadalajara remained the capital of Nueva Galicia with some modifications until the Mexican War of Independence.[20] Miguel Hidalgo entered San Pedro (now Tlaquepaque) on November 25, 1810, and the next day he was greeted effusively in Guadalajara. The city's workers had experienced poor living conditions and were swayed by promises of lower taxes and the abolition of slavery. Despite a soured welcome, due to the rebel army's violence toward city residents, especially royalists, Hidalgo kept his promise and, on December 6, 1810, slavery was abolished in Guadalajara, a proclamation which has been honored since the end of the war.[23] During this time, he founded the newspaper El Despertador Americano, dedicated to the insurgent cause.[20]

Royalist forces marched to Guadalajara, arriving in January 1811 with nearly 6,000 men.[24] Insurgents Ignacio Allende and Mariano Abasolo wanted to concentrate their forces in the city and plan an escape route should they be defeated, but Hidalgo rejected this idea. Their second choice was to make a stand at the Puente de Calderon just outside the city. Hidalgo had between 80,000 and 100,000 men and 95 cannons, but the better-trained royalists won, decimating the insurgent army and forcing Hidalgo to flee toward Aguascalientes. Guadalajara remained in royalist hands until near the end of the war.[24][25]'

On January 17, 1817, the insurgent army was again defeated on the outskirts of Guadalajara in the Battle of Calderón Bridge. New Galicia, now Jalisco, adhered to the Plan de Iguala on June 13, 1821.

In 1823, Guadalajara became the capital of the newly founded state of Jalisco.[20] In 1844, General Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga initiated a revolt against the government of President Antonio López de Santa Anna. Santa Anna personally ensured that the revolt was quelled. However, while Santa Anna was in Guadalajara, a revolt called the Three Hour Revolution brought José Joaquín Herrera to the presidency and put Santa Anna into exile.[26]

President Benito Juárez made Guadalajara the seat of his government in 1856, during the Reform War. French troops entered the city during the French Intervention in 1864, and it was retaken by Mexican troops in 1866.[20]

Despite the violence, the 19th century was a period of economic, technological and social growth for the city.[27] After Independence, small-scale industries developed, many of which were owned by European immigrants. Rail lines connecting the city to the Pacific coast and north to the United States intensified trade and allowed the shipment of products from rural areas of Jalisco. Ranch Culture became a very important aspect of Jalisco and Guadalajara's identities during this time.[22] From 1884 to 1890, electrical and railroad services, as well as the Guadalajara Observatory were established.[20]

20th century

Throughout the twentieth century, seeing growth in its industrial, tourist, and service industries, Guadalajara began a period of rapid transformation into the metropolis it is today. The city would gain the second largest economy in Mexico, following only by Mexico City. After the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Guadalajara became the second most populous city in the country. However, the decades that followed brought a number of regional wars in the states of Jalisco, Michoacán, and Guanajuato. The aftermath of the Great Depression took a further toll on the city. Fortunately, by the 1940s the city would experience industrial, demographic, and trade growth.

In 1910, the Mexican Revolution began, bringing an end to the Porfiriato. With conflict concentrated in the capital, Guadalajara experienced relative calm. After the Cristero Conflict, peace returned to Guadalajara and the city flourished, outgrowing its colonial roots. This period saw the birth of new schools of architecture that would decorate the city from the 1920s to the 1980s.

Guadalajara again experienced substantial growth after the 1930s,[28] and the first industrial park was established in 1947.[20] Its population surpassed one million in 1964,[20] and by the 1970s it was Mexico's second-largest city[28] and the largest in western Mexico.[22] Most of the modern city's urbanization took place between the 1940s and the 1980s, with the population doubling every ten years until it stood at 2.5 million in 1980.[29] The population of the municipality has stagnated, and even declined, slowly but steadily, since the early 1990s.[30]

The increase in population brought with it an increase in the size of what is now called Greater Guadalajara, rather than an increase in the population density of the city. Migrants coming into Guadalajara from the 1940s to the 1980s were mostly from rural areas and lived in the city center until they had enough money to buy property. This property was generally bought in the edges of the city, which were urbanizing into fraccionamientos, or residential areas.[31] In the 1980s, it was described as a "divided city" east to west based on socioeconomic class. Since then, the city has evolved into four sectors, which are still more or less class-centered. The upper classes tend to live in Hidalgo and Juárez in the northwest and southwest, while the lower classes tend to live in the city center, Libertad in the northeast, and southeast in Reforma. However, lower class development has expanded on the city's periphery and upper and middle classes are migrating toward Zapopan, making the situation less neatly divided.[32]

Since 1996, the activity of multinational corporations has had a significant effect on the economic and social development of the city. The presence of companies such as Kodak, Hewlett-Packard, Motorola and IBM has been based on production facilities built outside the city proper, bringing in foreign labor and capital. This was made possible in the 1980s by surplus labor, infrastructure improvements, and government incentives. These companies focus on electrical and electronic items, which is now one of Guadalajara's two main products (the other being beer). This has internationalized the economy, steering it away from manufacturing and toward services, dependent on technology and foreign investment. This has not been favorable for the unskilled working class and traditional labor sectors.[33]

The 1992 Guadalajara explosions occurred on April 22, 1992, when gasoline explosions in the sewer system over four hours destroyed 8 km (5 mi) of streets in the downtown district of Analco.[34] Gante Street was the most damaged. Officially, 206 people were killed, nearly 500 injured and 15,000 were left homeless. The estimated monetary damage ranges between $300 million and $1 billion. The affected areas can be recognized by their more modern architecture.[35]

Three days before the explosion, residents started complaining of a strong gasoline-like smell coming from the sewers. City workers were dispatched to check the sewers and found dangerously high levels of gasoline fumes. However, no evacuations were ordered. An investigation into the disaster found that there were two precipitating causes. The first was new water pipes that were built too close to an existing gasoline pipeline. Chemical reactions between the pipes caused erosion. The second was a flaw in the sewer design that did not allow accumulated gases to escape.[36]

Arrests were made to indict those responsible for the blasts.[37] Four officials of Pemex (the state oil company) were indicted and charged on the basis of negligence. Ultimately, however, these people were cleared of all charges.[38] Calls for the restructuring of PEMEX were made but they were successfully resisted.[39]

The 1990s were marked by events such as the explosions of April 22, 1992, the Mexican peso crisis of 1994, and the murder of the Cardinal Juan Jesús Posadas Ocampo in 1993.[40] The 1992 explosions caused massive infrastructure damage to hundreds of houses, avenues, streets, and businesses in the Analco neighborhood (barrio), "without a clear delineator of information and responsibilities to date,"[41] in one of the most tragic events in the history of Guadalajara. The investigation of the facts lasted more than 11 years in which insufficient evidence was found to appoint a manager,[42] investigations are now closed attributing the events to an accident.[42] This event, in addition to Mexico's 1994 economic crisis, resulted in the loss of Guadalajara's industrial power.[42]

Modern era

The city has hosted numerous important international events, such as the first Cumbre Iberoamericana in 1991; the Third Summit of Heads of State and Governments of Latin America, the Caribbean, and the European Union in 2004; the Encuentro Internacional de Promotores y Gestores Culturales in 2005; and the 2011 Pan American Games. It was named the American Capital of Culture in 2005 and the Ciudad Educadora (Educator City). in 2006. It was recognized as Mexico's first Smart City due to its use of developing technology.[43] During each government period, the city went through structural plans with which new areas and commercial hubs were born and with which transnational corporations and international industries arrived in the city. The city housed the first shopping malls in Mexico.

The city expanded rapidly before merging with the Zapopan municipality. Among the developments created during this period were the Guadalajara Expo, the light rail, shopping centers, the expansion of streets and avenues, and the birth and development of road infrastructure, services, tourism, industrial, etc. The first shopping center in Latin America emerged in the city,[44] the first urban electric-train system in Latin America,[45] and the first private university in Mexico.[46]

A 2007 survey entitled "Cities of the Future", FDi magazine ranked Guadalajara first among major Mexican cities and second among major North American cities in terms of economic potential, behind Chicago. The magazine also rated it as the most business-friendly Latin American city in 2007.[47]

Geography

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Guadalajara has a humid subtropical climate (Cwa), a temperate climate that is quite close to a tropical climate, featuring dry warm winters and wet, mildly hot summers. Guadalajara's climate is influenced by its high altitude and the general seasonality of precipitation patterns in western North America.

Although the temperature is warm year-round, Guadalajara has strong seasonal variation in precipitation. The northward movement of the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone brings a great deal of rain in the summer months, whereas, for the rest of the year, the climate is rather dry. The extra moisture during the wet months moderates the temperatures, resulting in cooler days and nights during this period. The highest temperatures are usually reached in May averaging 33 °C (91 °F), but can reach up to 37 °C (99 °F) just before the onset of monsoon season. March tends to be the driest month and July the wettest, with an average of 273 millimeters (10.7 in) of rain, over a quarter of the annual average of about 1,002 millimeters (39.4 in).

During the summer, afternoon storms are very common and can sometimes bring hail flurries to the city, especially toward late August or September. Winters are relatively warm despite the city's altitude, with January daytime temperatures reaching about 25 °C (77 °F) and nighttime temperatures about 10 °C (50 °F). However, the outskirts of the city (generally those close to the Primavera Forest) experience on average cooler temperatures than the city itself. There, temperatures around 0 °C (32 °F) can be recorded during the coldest nights. Frost may also occur during the coldest nights, but temperatures rarely fall below 0 °C (32 °F) in the city, making it an uncommon phenomenon. Cold fronts in winter can sometimes bring light rain to the city for several days in a row. Snowfall is extraordinarily rare, with the last recorded one occurring in December 1997, which was the first time in 116 years, as it had previously last fallen in 1881.[48]

| Climate data for Guadalajara, Mexico (1951–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 35.0 (95.0) |

38.0 (100.4) |

39.0 (102.2) |

41.0 (105.8) |

39.0 (102.2) |

38.5 (101.3) |

37.0 (98.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

36.0 (96.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

33.0 (91.4) |

41.0 (105.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 24.7 (76.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

32.5 (90.5) |

30.5 (86.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.4 (79.5) |

24.7 (76.5) |

27.9 (82.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.1 (62.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.9 (75.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

19.2 (66.6) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.5 (49.1) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

12.1 (53.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.5 (29.3) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 15.6 (0.61) |

6.6 (0.26) |

4.7 (0.19) |

6.2 (0.24) |

24.9 (0.98) |

191.2 (7.53) |

272.5 (10.73) |

226.1 (8.90) |

169.5 (6.67) |

61.4 (2.42) |

13.7 (0.54) |

10.0 (0.39) |

1,002.4 (39.46) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 2.1 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 3.5 | 15.2 | 21.6 | 20.0 | 15.5 | 6.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 90.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 60 | 57 | 50 | 46 | 48 | 63 | 71 | 72 | 71 | 68 | 63 | 64 | 61 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 204.6 | 226.0 | 263.5 | 261.0 | 279.0 | 213.0 | 195.3 | 210.8 | 186.0 | 220.1 | 225.0 | 189.1 | 2,673.4 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.6 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 6.1 | 7.3 |

| Source 1: Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (humidity, 1981–2000)[49][50][51] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1941–1990)[52] | |||||||||||||

Topography

Guadalajara's natural wealth is represented by the La Primavera Forest, Los Colomos, and the Barranca de Huentitán. The flora in these areas includes michoacan pines, several species of oak, sweetgum, ash, willow, and introduced trees such as poincianas, jacarandas, and ficus. It also includes orchids, roses, and various species of fungi. The fauna includes typical urban fauna in addition to 106 species of mammals, 19 species of reptiles, and six species of fish.

La Barranca de Huentitán (the Huentitán Forest) (also known as Barranca de Oblatos and Barranca de Oblatos-Huentitán) is a National Park located just north of the municipality of Guadalajara. The barranca (canyon) borders two colonias (neighborhoods) of the city, Oblatos and Huentitan. It covers approximately 1,136 hectares (2,810 acres), and varies 600 meters (2,000 ft) in altitude. The funicular railway in the park starts at 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) above sea level and rises to 1,520 meters (4,990 ft) above sea level. In the 16th century, during the Spanish Conquest, the Huentitán area including the canyon was the site of battles between local Indian populations and the Spanish. Later, it was the site of battles between different factions during the Mexican Revolution and the Cristero Rebellion.

The canyon is a biogeographic corridor that is home to four types of vegetation: deciduous tropical forest, gallery forest, heath vegetation, and secondary vegetation. In addition to introduced species, there are many native species of flora and fauna. The canyon is studied by national and international researchers as it contains great biological diversity due to its geographical location. On June 5, 1997, it was declared a Protected Natural Area, as an Area Subject to Ecological Conservation (Zona Sujeta a Conservación Ecológica).

La Cascada Cola de Caballo (The Horse Tail Waterfall) is located on the Guadalajara to Zacatecas road (Highway 54, km 15) a few kilometers from the Northern Peripheral, just after passing the village of San Esteban. The waterfall is fed by a stream from the Atemajac Valley. It is close to Guadalajara and a town with very little development, and as a result of poor ecological practices, it is very polluted.

El Bosque los Colomos, the Colomos Forest, is located in the northwestern part of Guadalajara along the Rio Atemajac. It is in a wealthy part of the metropolitan area, and has been developed for recreation rather than being preserved in its wild state. The river was once one of the main sources of water supply to the city, and today continues to provide water to some surrounding colonias (neighborhoods). Currently, this forest covers an area of 92 hectares (230 acres) in which pine trees, eucalyptus trees, and cedars predominate. The park has jogging tracks, gardens (including a Japanese garden), ponds, a bird lake, instructional areas for school field days, playgrounds, camping areas, and horses to ride.

Other places of interest around Guadalajara include Camachos Aquatic Natural Park, a commercial water park, and Barranca Colimilla, a beautiful canyon with hiking trails near Tonala, east of Guadalajara.

Urbanism

.jpg.webp)

Guadalajara's street plan has evolved over time into a radial urban plan, with five major routes into and out of the city. It is surrounded by ring roads.

The original city of Guadalajara was planned on a grid, with north–south and east–west intersecting streets. Over time, villages surrounding Guadalajara were incorporated into the city - first Analco to the southeast, then Mexicaltzingo to the south, Mezquitan to the north, and San Juan de Dios to the east, all of which introduced more variety to the plan. As it grew towards the west, it kept the original north–south orientation. As it grew towards the east, this grid was tilted towards the south-east to match up with the grids of the former towns Analco and San Juan de Dios, across the river from central Guadalajara on the eastern side of Rio San Juan de Dios (Rio San Juan de Dios is now underground; it runs beneath Calzada Independencia).

When the railway was introduced to Guadalajara in 1888, the southern part of the city began development, and its streets aligned with the grid to the east of the old Rio San Juan de Dios. Additional 20th-century expansion of the city introduced even more variety, as developers introduced different kinds of non-grid street plans in new areas. During the government of José de Jesús González Gallo, between 1947 and 1953, major public works changed the urban landscape of the historic center of the city.

Major controversial projects included the widening of Avenida 16 de Septiembre and Avenida Juárez, which were no longer adequate to handle car traffic in the center of the city. In the process, many buildings of architectural and historical value were demolished. Historical buildings around Guadalajara Cathedral were also demolished to leave large open spaces on the four sides of the Cathedral in the form of a large Latin cross, in which the cathedral is now centered. There were other, somewhat less controversial, projects to improve the flow of traffic and increase commerce in other parts of the city.

Districts

.jpg.webp)

Guadalajara is made up of more than 2,300 colonias (neighborhoods) in the Metropolitan Area. The oldest parts of the city include Centro (the oldest in the city), Santuario, Mexicaltzingo, Mezquitan, Analco, and San Juan de Dios. Private houses in the oldest sector of the city are mostly made up of one- and two-level houses, with architectural styles ranging from simple colonial architecture to the Churrigueresco, Baroque, and early nineteenth century European styles.

Just west of the oldest part of the city are upper-class colonias built in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, containing the neoclassical structures and houses of the Porfiriato. In the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s and 1950s well-to-do Tapatios expanded into colonias Lafayette, Americana, Moderna, and Arcos Vallarta. New architectural trends of the 1960s and 1970s also left their mark in colonias such as Colonia Americana, Vallarta Poniente, Moderna, Providencia, Vallarta San Jorge, Forest Gardens, and Chapalita.

The Metropolitan Area has more wealthy neighborhoods than any other part of western Mexico. These colonias are located both inside and outside the municipality of Guadalajara, including some in its neighboring municipalities of Zapopan and Tlajomulco, in the west and south. Some of these colonias are: Colinas de San Javier, Puerta de Hierro, Providencia, Chapalita, Jardines de San Ignacio, Ciudad del Sol, Valle Real, Lomas del Valle, Santa Rita, Monraz, Santa Anita Golf Club, El Cielo, Santa Isabel, Virreyes, Ciudad Bugambilias, Las Cañadas, and The Stay.

In general, residents in the west of the city are the wealthiest, while residents in the east are the poorest.

New development to accommodate the growing population is made up of a mix of middle-class colonias and housing complexes developed as part of government plans, and colonias developed less formally for working-class people. The Metropolitan Area extends to the west in colonias such as Pinar de la Calma, Las Fuentes, Paseos del Sol, El Colli Urbano, and La Estancia and extends to the east in colonias such as St. John Bosco, St. Andrew, Oblates, St. Onofre, Insurgents, Gardens of Peace, and Garden of Poets.

The expansion of the population creates a constant demand for more colonias and more government infrastructure services.

Parks

Parks and forests are important in Guadalajara; while many of the oldest neighborhoods of the municipality of Guadalajara do not have sufficient green spaces, of the three most important metropolitan areas in Mexico, the Guadalajara Metropolitan Area (ZMG) has the greenest areas and plants.

The most important parks are:

- Gardens (Jardínes)

- Jardín Dr. Atl

- Jardín Francisco Zarco

- El Jardín Botánico (Botanical Garden)

- Jardín del Santuario

- Glorieta Chapalita Zapopan

- Jardín de San Francisco de Asís

- Jardín de San Sebastián de Analco

- Jardín del Carmen

- Jardín del Museo Arqueológico (Garden of the Archaeological Museum)

- Jardín José Clemente Orozco

- Parks (Parques)

- Parque Ávila Camacho

- Parque de la Revolución (Parque Rojo to locals)

- Parque Mirador Independencia o Barranca de Huentitán

- Parque Mirador Dr. Atl Zapopan

- Parque Oblatos

- Parque Amarillo (Colonia Jardines Alcalde)

- Parque Talpita

- Parque Tucson (Colonia Jardines Alcalde)

- Parque Los Colomos

- Parque Morelos

- Parque de la Jabonera

- Parque Metropolitano Zapopan

- Parque Alcalde

- Parque Agua Azul

- Parque González Gallo

- Parque de la Solidaridad Tonalá

- Parque de la Liberación

- Parque de la Expenal (Explanada 18 de Marz)

- Parque Roberto Montenegro El Salto

- Parque San Rafael

- Parque San Jacinto

- Forests (Bosques)

- Bosque del Centinela – Zapopan

- Bosque de la Primavera – Zapopan, Tlajomulco y Tala

- Zoos (Zoológicos)

- Zoológico Villa Fantasía Zapopan

- Zoológico Guadalajara

Coat of arms

.svg.png.webp)

The coat of arms or seal of Guadalajara consists of a blue field, a pine of sinople outlined, two lions rampantes of color, opposite to forehead and the legs on the trunk, embroidery is of gold, consists of seven arms of gules. For stamp, closed helmet and for cimera a flag of gules, loaded with a cross of Jerusalem to the one that uses as shaft a lance of the same color, the lambrequins are of gold and blue alternated.

The blue field means loyalty and serenity, the pine of sinople means noble thoughts, the lions sovereignty and warlike spirit, the arms mean protection, favor and purity of the feelings, honor to the Battle of Baeza against the Moors in 1227. The helmet represents a degree of nobility, victory in the combat, the cross of Jerusalem means that the conquerors were descendants of the gentlemen of the crusades, and the lance signifies strength that is tempered by prudence.

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, granted the title of city to Guadalajara and granted the shield in 1539.

Demographics

The most current figures by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), confirmed in 2010, the municipality of Guadalajara has a population of approximately 1,495,189, with a population in the metropolitan area of 4,334,878, the most populous city in the state of Jalisco, the most conurbation-highest-population within the province of Jalisco of the Guadalajara metropolitan area, and the second-most populous city in Mexico; the first being Mexico City.

In 2007, the United Nations listed the world's 100 most populous urban agglomerations. Mexico excelled with three cities on the list: Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey. Guadalajara ranked 66th in these cities, followed by Sydney and Washington, D.C. On the Latin American list, Guadalajara ranked 10th.

The municipality of Guadalajara is located in the center of the State, a little to the east, at coordinates 20-&36' 40" to 20- 45' 00" north latitude and 103- 16' 00" to 103- 24' 00" west-latitude and 103-&16' 00" to 103- 24' 00" west-west longitude, at a height of 1700 meters above sea level.

The municipality of Guadalajara is bounded to the north by Zapopan and Ixtlahuacán del Río, to the east by Tonalá and Zapotlanejo, to the south with Tlaquepaque and to the west with Zapopan.

Guadalajara Metropolitan Area

The Guadalajara metropolitan area is the second most populous metropolitan area in the country and the agglomeration has six central municipalities and three exterior municipalities. The central municipalities are Guadalajara, Zapopan, Tlaquepaque, Tonalá, Tlajomulco, and El Salto, Jalisco. The exterior municipalities are Ixtlahuacán de los Membrillos, Juanacatlán, and Zapotlanejo.

| Year | 1738 | 1865 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 24,560 | 69,670 | 740,394 | 1,199,391 | 1,626,152 | 1,650,205 | 2,633,216 | 3,646,319 | 4,374,370 | 4,654,134 | 5,002,466 |

The growth of the city is due to Guadalajara absorbing the closest communities. This was the case with the former communities Atemajac, Huentitán, Tetlán, Analco, Mexicaltzingo, Mezquitan, and San Andrés, among others.

Some of the closest communities to Guadalajara:

- Ixtlahuacán del Río (21.7 km from the municipal seat of Guadalajara,20°51′48.96″N 103°14′22.57″W).

- Santa Anita (19.6 km from Guadalajara's municipal seat, 20°32′59.09″N 103°26′29.50″W).

- Santa Cruz de las Flores (27.9 km from the municipal seat of Guadalajara,20°28′49.33″N 103°30′29.09″W).

- Nuevo México (14 km from municipal seat of Guadalajara, 20°45′47.02″N 103°26′27.24″W).

- Tesistán (20,8 km from the municipal seat of Guadalajara, 20°47′54.91″N 103°28′39.85″W).

- La Primavera (24.4 km from the municipal seat of Guadalajara,20°37′59.25″N 103°33′35.37″W).

Economy

Guadalajara has the third-largest economy and industrial infrastructure in Mexico[53] and contributes 37% of the state of Jalisco's total gross production. Its economic base is strong and well-diversified, mainly based on commerce and services, although the manufacturing sector plays a defining role.[54] It is ranked in the top ten in Latin America in gross domestic product and the third-highest ranking in Mexico.

In its 2007 survey entitled "Cities of the Future", FDi magazine ranked Guadalajara highest among major Mexican cities and designated Guadalajara as having the second strongest economic potential of any major North American city behind Chicago. FDI ranked it as the most business-friendly Latin American city in 2007.[55] The same research noted Guadalajara as a "city of the future" due to its youthful population, low unemployment and large number of recent foreign investment deals; it was found to be the third most business-friendly city in North America.[55]

In 2009 Moody's Investors Service assigned ratings of Ba1 (Global Scale, local currency) and A1.mx (Mexican national scale). During the prior five years, the municipality's financial performance had been mixed but had begun to stabilize in the latter two years. Guadalajara manages one of the largest budgets among Mexican municipalities and its revenue per capita indicator (Ps. $2,265) places it above the average for Moody's-rated municipalities in Mexico.[54]

The city's economy has two main sectors. Commerce and tourism employ most: about 60% of the population. The other is industry, which has been the engine of economic growth and the basis of Guadalajara's economic importance nationally even though it employs only about a third of the population.[20][54][56] Industries here produce products such as food and beverages, toys, textiles, auto parts, electronic equipment, pharmaceuticals, footwear, furniture and steel products.[20][56]

Two of the major industries have been textiles and shoes, which are still dynamic and growing.[57] Sixty percent of manufactured products are sold domestically, while forty percent are exported, mostly to the United States.[58] This makes Guadalajara's economic fortunes dependent on those of the U.S., both as a source of investment and as a market for its goods.[59]

The city has to compete with China, especially for electronics industries which rely on high volume and low wages. This has caused it to move toward high-mix, mid-volume, and value-added services, such as automotive. However, its traditional advantage of proximity to the U.S. market is one reason Guadalajara stays competitive.[59] Mexico ranked third in 2009 in Latin America for the export of information technology services, behind Brazil and Argentina. This kind of service is mostly related to online and telephone technical support. The major challenge this sector has is the lack of university graduates who speak English.[60]

Technology

The electronics and information technology sectors that have nicknamed the city the "Silicon Valley of Mexico."[58] Guadalajara is the main producer of software, electronic and digital components in Mexico. Telecom and computer equipment from Guadalajara accounts for about a quarter of Mexico's electronics exports.[59] Companies such as General Electric, IBM, SANMINA, Intel Corporation, HCL Technologies, Hitachi Ltd., Hewlett Packard Enterprise, HP Inc, Siemens, Flextronics, Oracle, Wipro, TCS, Cognizant Technology Solutions, and Jabil Circuit have facilities in the city or its suburbs.[58] This phenomenon began after the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). International firms started building facilities in Mexico, especially Guadalajara, displacing Mexican firms, especially in information technology. One of the problems this has created is that when there are economic downturns, these international firms scale back.[61]

Guadalajara was selected as "Smart City" in 2013 by IEEE, the world's largest professional association for the advancement of technology.

Several cities invest in the areas of research to design pilot projects and as an example, in early March in 2013 was the first "Cluster Smart Cities" in the world, composed of Dublin, Ireland; San Jose, California; Cardiff, Wales, and Guadalajara, Jalisco, whose objective is the exchange of information and experiences that can be applied in principle to issues of agribusiness and health sciences.

The Secretariat of Communications and Transportation also reported that Guadalajara, Jalisco was chosen as the official venue for the first "Digital Creative City of Mexico and Latin America", which will be the spearhead for Mexico to consolidate the potential in this area.

The "Cluster Smart Cities" unprecedented in the world, will focus on what each of these cities is making in innovation and the creation of an alliance to attract technology. The Ministry of Innovation, Science, and Technology (SICyT ) of Jalisco, said the combination of talent development investments allows Jalisco to enter the "knowledge economy."

From 25 to 28 October 2015, the city was the venue for the first conference of the Smart Cities Initiative.[62][63]

Industries

Most of the economy revolves around commerce, employing 60% of the population.[20] This activity has mainly focused on the purchase and sale of the following products: food and beverages, textiles, electronic appliances, tobacco, cosmetics, sports articles, construction materials, and others. Guadalajara's commercial activity is second only to Mexico City.[56]

The city is the national leader in the development and investment of shopping malls. Many shopping centers have been built, such as Galeries Plaza, one of the largest shopping centers in Latin America, and Andares. Galerías Guadalajara covers 160,000 m2 (1,722,225.67 sq ft) and has 220 stores. It contains the two largest movie theaters in Latin America, both with IMAX screens. It hosts art exhibits and fashion shows and has an area for cultural workshops. Anchor stores includes Liverpool and Sears and specialty stores such as Hugo Boss, Max Mara, Lacoste, Tesla Motors, Costco.[64] Best Buy opened its first Guadalajara store here. It has an additional private entrance on the top floor of the adjacent parking lot. Another Best Buy store was inaugurated in Ciudadela Lifestyle Center mall, which was the chain's third-largest in the world, according to the company.

Andares is another important commercial center in Zapopan. This $530 million mixed-use complex opened in 2008, designed by renowned Mexican Sordo Madaleno architecture firm features luxury residences and a high-level mall anchored by two large department stores, Liverpool and El Palacio de Hierro. The 133,000 m2 (1,400,000+ sq ft) mall offers hundreds of stores, a big food court located on the second floor, and several restaurants at the Paseo Andares.

A large segment of the commercial sector caters to tourists and other visitors. Recreational tourism is mainly concentrated in the historic downtown.[20] In addition to being a cultural and recreational attraction and thanks to its privileged geographical location, the city serves as an axis to nearby popular beach destinations such as Puerto Vallarta, Manzanillo and Mazatlán.[56] Other types of visitors include those who travel to attend seminars, conventions and other events in fields such as academic, entertainment, sports, and business. The best-known venue for this purpose is the Expo Guadalajara, a large convention center surrounded by several hotels. It was built in 1987, and it is considered the most important convention center in Mexico.

Foreign trade

Most of Guadalajara's economic growth since 1990 has been tied with foreign investment. International firms have invested here to take advantage of the relatively cheap but educated and highly productive labor, establishing manufacturing plants that re-export their products to the United States, as well as provide goods for the domestic Mexican market.[65]

A media report in early October 2013 stated that five major Indian IT (information technology) companies have established offices in Guadalajara, while several other Indian IT companies continue to explore the option of expanding to Mexico. Due to the competitiveness in the Indian IT sector, companies are expanding internationally and Mexico offers an affordable opportunity for Indian companies to better position themselves to enter the United States market. The trend emerged after 2006 and the Mexican government offers incentives to foreign companies.[66]

Exports from the city went from US$3.92 billion in 1995 to 14.3 billion in 2003.[56] From 1990 to 2000, socio-economic indicators show that quality of life improved overall; however, there is still a large gap between the rich and the poor, and the rich have benefited from the globalization and privatization of the economy more than the poor.[67]

International investment has affected the labor market in the metro area and that of the rural towns and villages that surround it. Guadalajara is the distribution center for the region and its demands have led to a shifting of employment, from traditional agriculture and crafts to manufacturing and commerce in urban centers. This has led to mass migration from the rural areas to the metropolitan area.[65]

Culture

Guadalajara has a lively cultural life. The city exhibits works by international artists and is a must-see for international cultural events whose radius of influence reaches most of the countries of Latin America, including the southwestern United States.

Its historic center houses colonial buildings of a religious and civil character, which stand out for their architectural and historical significance, and constitute a rich mixture of styles whose root is found in indigenous cultural contributions (mainly of incorporated into the Mozarabic and the castilian), and later in modern European influences (mainly French and Italian). The historic center also has museums, theaters, galleries, libraries, auditoriums, and concert halls. Some of these buildings date from the sixteenth and seventeenth century, such as the Cathedral of the Archdiocese of Guadalajara, among others.

The city has several radio stations focused on culture, one of them being Red Radio University of Guadalajara (XHUG-F), which is transmitted to the rest of the state and neighboring states and internationally through the Internet; it is also the first broadcaster via podcast in the country.[68] The city produces a fully cultural television channel, XHGJG-TV; Guadalajara is the only city to produce a cultural cutting channel in the country in addition to the Mexico, D.F.A. in Mexico City.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

This city has been the cradle and dwelling of distinguished poets, writers, painters, actors, film directors and representatives of the arts, etc., such as José Clemente Orozco, Dr. Atl, Roberto Montenegro, Alejandro Zohn, Luis Barragán, Carlos Orozco Romero, Federico Fabregat, Raul Anguiano, Juan Soriano, Javier Campos Cabello, Martha Pacheco, Alejandro Colunga, José Fors, Juan Kraeppellin, Davis Birks, Carlos Vargas Pons, Jis, Trino, Erandini, Enrique Oroz, Rubén Méndez, Mauricio Toussaint, Scott Neri, Paula Santiago, Edgar Cobian, L. Felipe Manzano, and (the artist formerly known as Mevna); the freeplay guitarist and music composer for the movies El Mariachi and The Legend of Zorro, Paco Rentería; important exponents of literature such as Juan Rulfo, Francisco Rojas, Agustín Yáñez, Elías Nandino, Idella Purnell, Jorge Souza, among others; classic repertoire composers such as Gonzalo Curiel, José Pablo Moncayo, Antonio Navarro, Ricardo Zohn, Carlos Sánchez-Gutiérrez and Gabriel Pareyon; film directors such as Felipe Cazals, Jaime Humberto Hermosillo, Erik Stahl, Guillermo del Toro; and actors such as Katy Jurado, Enrique Alvarez Felix, and Gael García Bernal.

Guadalajara was the first Mexican city to be accepted as a member of the International Association of Educational Cities[69][70] due to its strong character and identity, potential for economic development through culture.

Guadalajara was designated as the World Book Capital for 2022 by UNESCO.[71]

Despite the Guadalajara area historically being an ethnically Caxcan region, the Nahua peoples form the majority of Guadalajara's indigenous population.[72] There are several thousand indigenous language speakers in Guadalajara although the majority of the indigenous population is integrated within the general population and can speak Spanish.[72]

Museums

.JPG.webp)

The museums in Guadalajara are an extension of the cultural infrastructure of this city. Many of them stand out for their architectural and historical significance. There are more than 189 forums of art exhibition among cultural centers, museums, private galleries, and cultural spaces of the town hall, several of them with centuries of existence and some others in the process of being built. The museums in Guadalajara belong to the cultural framework of the city, among which are in all its genres exhibiting history, paleontology, archeology, ethnography, paintings, crafts, plastic, photography, sculpture, works of circuits international art, etc.

Guadalajara has twenty two museums, which include the Regional Museum of Jalisco, the Wax Museum, the Trompo Mágico children's museum and the Museum of Anthropology.[73] The Former Hospice Cabañas in the historic center is a World Heritage Site.[74] For these attributes and others, the city was named an American Capital of Culture in 2005.[75]

Guadalajara and the surrounding metropolitan area have numerous public, private, and digital libraries for the search and consultation of information. The promotion of culture and the enrichment of reading have made it easier for the citizen to require several facilities in the city. Some of the libraries also have a physical enclosure—among them the historic Octavio Paz Ibero-American Library of the University of Guadalajara and the Public Library of the State of Jalisco located in the adjoining city of Zapopan—with options for querying digital information over the Internet.

The Jalisco Regional Museum (formerly the seminary of San José) was built at the beginning of the 18th century to be the Seminario Conciliar de San José. From 1861 to 1914, it housed a school called Liceo de Varones. In 1918, it became the Museum of Fine Arts. In 1976, it was completely remodeled for its present use. The museum displays its permanent collection in 16 halls, 15 of which are dedicated to Paleontology, Pre-History, and Archeology. One of the prized exhibits is a complete mammoth skeleton. The other two halls are dedicated to painting and history. The painting collection includes works by Juan Correa, Cristóbal de Villalpando and José de Ibarra.[20][76]

Architecture

The style of architecture prevalent in Europe during the founding of Guadalajara is paralleled in the city's colonial buildings. The Metropolitan Cathedral and Teatro Degollado are the purest examples of neoclassical architecture. The historical center hosts religious and civil colonial buildings, which are noted for their architectural and historical significance and are a rich mix of styles that are rooted in indigenous cultural contributions (mainly from Ute origin), incorporated in the Mozarabic and castizo, and later in modern European influences (mainly French and Italian) and American (specifically, from the United States).

Guadalajara's historical center has an assortment of museums, theaters, galleries, libraries, auditoriums and concert halls, particular mention may be made to Former Hospice Cabañas (which dates from the 18th century), the Teatro Degollado (considered the oldest opera house in Mexico), the Teatro Galerías and the Teatro Diana. The Former Hocpice Cabañas, which is home to some of the paintings (murals and easel) by José Clemente Orozco, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997. Among the many structures of beauty is the International Headquarters Temple of La Luz del Mundo in Colonia Hermosa Provincia, which is the largest in Latin America.

During the Porfiriato the French style invaded the city because of the passion of former president Porfirio Díaz in the trends of French style, also Italian architects were responsible for shaping the Gothic structures that were built in the city. The passage of time reflected different trends from the baroque to churrigueresque, Gothic and neoclassical pure.

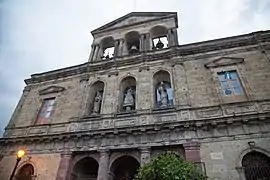

_00281_templo_de_san_felipe_neri.jpg.webp)

The French-inspired "Lafayette" neighborhood has many fine examples of early 20th-century residences that were later converted into boutiques and restaurants.

Even the architectural lines typical of the decades of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s the Art Deco and bold lines of postmodern architects of the time. Architectural styles found in the city include Baroque, Viceregal, Neoclassical, Modern, Eclectic, Art Deco and Neo-Gothic.

The modern architecture of Guadalajara has numerous figures of different architectural production from the neo-regionalism to the primitiveness of the 1960s. Some of these architects are: Rafael Urzua, Luis Barragán, Ignacio Díaz Morales, Pedro Castellanos, Eric Coufal, Julio de la Peña, Eduardo Ibáñez Valencia, Félix Aceves Ortega

Guadalajara's modern architecture has figures of diverse architectural output from neo-regionalism to the brutalism of the 1970s. One of these architects are: Rafael Urzua, Luis Barragán, Ignacio Díaz Morales, Pedro Castellano, Eric Coufal, July de la Peña, Eduardo Ibáñez Valencia

Festivals

.jpg.webp)

Guadalajara is also known for several large cultural festivals. The International Film Festival of Guadalajara[77] is a yearly event which happens in March. It mostly focuses on Mexican and Latin American films; however, films from all over the world are shown. The event is sponsored by the Universidad de Guadalajara, CONACULTA, the Instituto Mexicano de Cinematographía as well as the governments of the cities of Guadalajara and Zapopan. The 2009 festival had over 200 films shown in more than 16 theaters and open-air forums, such as the inflatable screens set up in places such as Chapultepec, La Rambla Cataluña, and La Minerva. In that year, the event gave out awards totaling US$500,000. The event attracts names such as Mexican director Guillermo del Toro, Greek director Constantin Costa-Gavras, Spanish actor Antonio Banderas and U.S. actor Edward James Olmos.[78]

The Guadalajara International Book Fair is the largest Spanish-language book fair in the world, held each year over nine days at the Expo Guadalajara.[79][80] Over 300 publishing firms from 35 countries regularly attend, demonstrating the most recent productions in books, videos and new communications technologies. The event awards prizes such as the Premio FIL for literature, the Premio de Literatura Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, also for literature, and the Reconocimento al Mérito Editorial for publishing houses. There is an extensive exposition of books and other materials in Spanish, Portuguese and English, covering academia, culture, the arts and more for sale. More than 350,000 people attend from Mexico and abroad.[79] In 2009, Nobel prize winner Orhan Pamuk, German children's author Cornelia Funke and Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa participated with about 500 other authors present.[81] Activities include book presentations, academic talks, forums, and events for children.[80]

The Danza de los Tastoanes is an event hosted annually on July 25 at the Municipal President's building, where the folklore dancers perform one of the oldest traditional dances and combat battle performance to honor the combats against the Spanish.[82]

The Festival Cultural de Mayo (May Cultural Festival) began in 1988. In 2009, the event celebrated the 400th anniversary of relations between Mexico and Japan, with many performances and exhibitions relation to Japanese culture. The 2009 festival featured 358 artists in 118 activities. Each year a different country is "invited." Past guests have been Germany (2008), Mexico (2007), Spain (2006) and Austria (2005). France is the 2013 guest.[83]

The Expo Ganadera is an event hosted annually in the month of October where people from all over the country attend to display the best examples of the breed and their quality that is produced in Jalisco. The event also works to promote technological advances in agriculture. The event also has separate sections for the authentic Mexican cuisine, exhibitions of livestock, charreria, and other competitions that display the Jalisco traditions.[84]

Notable festivals include:

- May Cultural Festival

- Guadalajara International Book Fair,[85] this fair is held every year, thanks to the auspices of the University of Guadalajara, during the last week of November. It includes a large exhibition of consolidated, independent, university, national, international publishers; books and lectures are presented; it has a special area for children and young people; it is very significant for showing during the ten days of the fair to a guest country (or region, or community), to which a pavilion is dedicated to exposing the most representative of its culture. In the FIL, as it is popularly known, several awards are awarded, the most representative is the Juan Rulfo Award' Latin American and Caribbean Literature Award (formerly known as "Juan Rulfo", in honor of this author jalisciense).

- The festivities of October: These are the traditional festivals of Guadalajara, have been held since 1965 being the first headquarters the Agua Azul Park and years later it would change headquarters to the Benito Juárez auditorium that is where this celebration is currently held. Its main attractions are the mechanical games, the palenque and the auditorium where various artists, especially Mexican music are performed every night during this celebration of the October festivities.

- The Feast of the Dolls (Guadalajara International Puppet Festival).

- The International Meeting of Mariachi and Charrería. As its name says, various mariachis from different parts of the world gather. As well as the charros that come from various parts to demonstrate the national sport of Mexico. It starts with a parade and over the days events are held in various scenarios throughout the city. It is held between the months of August and September.

- Expo Ganadera.Es the largest and most important of its kind in the country. It is usually performed during the month of October.

- The Guadalajara International Film Festival (known as Guadalajara Film Fest). With more than twenty years of experience, FICG is the most important event in Mexico in terms of film, which includes an exhibition of films, an encounter with filmmakers and actors (talent campus), and the contest of realizations that are awarded in several categories: Ibero-American and Mexican short film, Mexican and Latin American documentary, a fictional feature film, among which the "Mayahuel" in which a trajectory is awarded.

- The International Festival of Contemporary Dance "Onésimo González." It was organized since 1999 organized by the Ministry of Culture of the Government of the State of Jalisco and the National Dance Coordination of INBA. Having in this choreographic examples of the most outstanding dance groups of the state of Jalisco, with some guest, national and international companies; promoting cultural exchange within Guadalajara, while offering open master classes to the public to enrich the dance language in this state. Performing every October at the Art and Culture Forum of this city.

- Expo-International Friendship Fair. This city has been the cradle and shelter of distinguished [poet], writers, painters, actors, filmmakers and representatives of art internationally. One work that accounts for the richness of the poets of this city is the book Major Poetry in Guadalajara (Poetic Annotations and Criticisms).

Landmarks

The historic downtown of Guadalajara is the oldest section of the city, where it was founded and where the oldest buildings are. It centers on Paseo Morelos/Paseo Hospicio from the Plaza de Armas, where the seats of ecclesiastical and secular power are, east toward the Plaza de los Mariachis and the Former Hospice Cabañas. The Plaza de Armas is a rectangular plaza with gardens, ironwork benches and an ironwork kiosk which was made in Paris in the 19th century.[20][76]

- Landmarks and monuments of Guadalajara

Hospicio Cabañas, built in 1805-1845 by Manuel Tolsá, José Gutiérrez, Pedro José Ciprés.[86][87][88]

Hospicio Cabañas, built in 1805-1845 by Manuel Tolsá, José Gutiérrez, Pedro José Ciprés.[86][87][88] Palacio del Gobierno

Palacio del Gobierno Guadalajara Cathedral, built between 1561-1618 (spires and dome were rebuilt between 1851-1854) by Martín Casillas, José Gutiérrez, Manuel Gómez Ibarra.[89][90]

Guadalajara Cathedral, built between 1561-1618 (spires and dome were rebuilt between 1851-1854) by Martín Casillas, José Gutiérrez, Manuel Gómez Ibarra.[89][90] Palacio Legislativo

Palacio Legislativo Guadalajara Monument

Guadalajara Monument Señora del Pilar Church

Señora del Pilar Church![Palacio de Velasco [es]](../I/Palacio_de_Velasco_(Guadalajara%252C_M%C3%A9xico).jpg.webp) Palacio de Velasco

Palacio de Velasco.jpg.webp) Rotonda de los Hombres Ilustres

Rotonda de los Hombres Ilustres.jpg.webp) Guadalajara City Hall

Guadalajara City Hall

Palacio de Justicia

Palacio de Justicia![Sanctuary of Our Lady of Guadalupe [es], built in 1777-1781 by Antonio Alcalde y Barriga.](../I/Santuario_de_Guadalupe_-_GDL_JAL.jpg.webp)

Church of Nuestra Señora de la Merced, built in 1650-1721 by Francisco de Pineda for the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mercy.[99][100][101]

Church of Nuestra Señora de la Merced, built in 1650-1721 by Francisco de Pineda for the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mercy.[99][100][101]

Within Guadalajara's historic downtown, there are many squares and public parks: Morelos Park, Mariachis Square, Founders Square, Tapatía Square, Agave Square, Parque Revolucion, Sanctuary Garden, Arms Square, Plaza de la Liberacion, Guadalajara Square and the Jalisco Famous People Roundabout, the last four of which surround the cathedral to form a Latin Cross.[102]

Construction began on the Metropolitan Cathedral in 1558 and the church was consecrated in 1616. Its two towers were built in the 19th century after an earthquake destroyed the originals. They are considered one of the city's symbols. The architecture is a mix of Gothic, Baroque, Moorish and Neoclassical. The interior has three naves and eleven side altars, covered by a roof supported by 30 Doric columns.[76]

The Jalisco Famous People Roundabout (Rotonda de los Hombres Ilustres) is a monument made of quarried stone, built in 1952 to honor the memory of distinguished people from Jalisco. A circular structure of 17 columns surrounds 98 urns containing the remains of those honored. Across the street is the municipal palace which was built in 1952. It has four façades of quarried stone. It is mostly of Neoclassical design with elements such as courtyards, entrances, and columns that imitate the older structures of the city.[20][76]

The Palace of the State Government is in Churrigueresque and Neoclassical styles and was begun in the 17th century and finished in 1774. The interior was completely remodeled after an explosion in 1859. This building contains murals by José Clemente Orozco, a native of Jalisco, including "Lucha Social", "Circo Político", "Las Fuerzas Ocultas", and "Hidalgo", which depicts Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla with his arm raised above his head in anger at the government and the church.[76]

The cathedral is bordered to the east by the Freedom Square, nicknamed the Two Cups Square (Plaza de las Dos Copas), referring to the two fountains on the east and west sides. Facing this square is the Degollado Theater (Teatro Degollado). It was built in the mid-nineteenth century in Neoclassical design. The main portal has a pediment with a scene in relief called "Apollo and the Muses" sculpted in marble by Benito Castañeda. The interior vaulted ceiling is painted with a fresco by Jacobo Gálvez and Gerardo Suárez which depicts a scene from the Divine Comedy. Behind the theater is another square with a fountain called the Founders Fountain (Fuente de los Fundadores). The square is in the exact spot where the city was founded and contains a sculpture depicting Cristóbal de Oñate at the event.[20]

Between the Cathedral and the Hospice is the large Plaza Tapatía, which covers 70,000 m2 (750,000 sq ft). Its centerpiece is Inmolación de Quetzalcóatl.[20] Southeast of this square is the Mercado Libertad, also called the Mercado de San Juan de Dios, one of the largest traditional markets in Mexico. The Temple of San Juan de Dios, a Baroque church built in the 17th century, is next to the market.[76]

At the far east end is the Plaza de los Mariachis and the Former Hospice Cabañas. The Plaza de los Mariachis is faced by restaurants where one can hear live mariachis play, especially at night. The Cabañs Former Hospice extends along the entire east side of the Plaza. This building was constructed by Manuel Tolsá beginning in 1805 under orders of Carlos III. It was inaugurated and began its function as an orphanage in 1810, in spite of the fact that it would not be finished until 1845. It was named after Bishop Ruiz de Cabañas y Crespo. The façade is Neoclassical and its main entrance is topped by a triangular pediment. Today, it is the home of the Instituto Cultural Cabañas (Cabañas Cultural Institute) and its main attraction is the murals by José Clemente Orozco, which cover the main entrance hall. Among these murals is "Hombre del Fuego" (Man of Fire), considered to be one of Orozco's finest works.[20][76]

Off this east–west axis are other significant constructions. The Legislative Place is Neoclassical and was originally built in the 18th century. It was reconstructed in 1982. The Palace of Justice was finished in 1897. The Old University Building was a Jesuit college named Santo Tomás de Aquino. It was founded in 1591. It became the second Mexican University in 1792. Its main portal is of yellow stone. The Casa de los Perros (House of the Dogs) was constructed in 1896 in Neoclassical design.[20] On Avenida Juarez is the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora del Carmen which was founded between 1687 and 1690 and remodeled completely in 1830. It retains its original coat of arms of the Carmelite Order as well as sculptures of the prophets Elijah and Elisha. Adjoining it is what is left of the Carmelite monastery, which was one of the richest in New Spain.[76]

Music

Mariachi music is strongly associated with Guadalajara both in Mexico and abroad even though the musical style originated in the nearby town of Cocula, Jalisco. The connection between the city and mariachi began in 1907 when an eight-piece mariachi band and four dancers from the city performed on stage at the president's residence for both Porfirio Díaz and the Secretary of State of the United States. This made the music a symbol of west Mexico, and after the migration of many people from the Guadalajara area to Mexico City (mostly settling near Plaza Garibaldi), it then became a symbol of Mexican identity as well.[103]

Guadalajara hosts the Festival of Mariachi and Charreria, which began in 1994. It attracts people in the fields of art, culture and politics from Mexico and abroad. Regularly the best mariachis in Mexico participate, such as Mariachi Vargas, Mariachi de América and Mariachi los Camperos de Nati Cano. Mariachi bands from all over the world participate, coming from countries such as Venezuela, Cuba, Belgium, Chile, France, Australia, Slovak Republic, Canada and the United States.

The events of this festival take place in venues all over the metropolitan area,[104][105] and include a parade with floats.[105] In August 2009, 542 mariachi musicians played together for a little over ten minutes to break the world record for largest mariachi group. The musicians played various songs ending with two classic Mexican songs "Cielito Lindo" and "Guadalajara." The feat was performed during the XVI Encuentro Internacional del Mariachi y la Charreria. The prior record was 520 musicians in 2007 in San Antonio, Texas.[106]

In the historic center of the city is the Plaza de los Mariachis, named such as many groups play here. The plaza was renovated for the 2011 Pan American Games in anticipation of the crowds visiting. Over 750 mariachi musicians play traditional melodies on the plaza, and along with the restaurants and other businesses, the plaza supports more than 830 families.[107]

A recent innovation has been the fusion of mariachi melodies and instruments with rock and roll performed by rock musicians in the Guadalajara area. An album collecting a number of these melodies was produced called "Mariachi Rock-O." There are plans to take these bands on tour in Mexico, the United States and Europe.[108]

The city is also host to several dance and ballet companies such as the Chamber Ballet of Jalisco, the Folkloric Ballet of the University of Guadalajara, and the University of Guadalajara Contemporary Ballet.

The city is home to a renowned symphony orchestra. The Orquesta Filarmónica de Jalisco (Jalisco Philharmonic Orchestra) was founded by José Rolón in 1915. It held concerts from that time until 1924, when state funding was lost. However, the musicians kept playing to keep the orchestra alive. This eventually caught the attention of authorities and funding was restated in 1939. Private funding started in the 1940s and in 1950, an organization called Conciertos Guadalajara A. C. was formed to continue fundraising for the orchestra. In 1971, the orchestra became affiliated with the Department of Fine Arts of the State of Jalisco. The current name was adopted in 1988/ International soloists such as Paul Badura-Skoda, Claudio Arrau, Jörg Demus, Henryck Szeryng, Nicanor Zabaleta, Plácido Domingo, Kurt Rydl and Alfred Brendel have performed with the organization. Today the orchestra is under the direction of Marco Parisotto.[109]

Cuisine

As in the rest of Mexico, food in Guadalajara is a mix of pre-Hispanic and Spanish influences. Typical Mexican dishes, such as pozole, tamales, sopes, enchiladas, tacos, menudo (soup), carne en su jugo and frijoles charros are popular.

One dish specific to Guadalajara is the "torta ahogada." It consists of a salted bun or roll (typically birote) smeared with refried beans, with fried pork cut into pieces — also known as "carnitas" — all in tomato sauce seasoned with spices. It is eaten with onions reduced in lemon and hot sauce. Accompanying drinks can include tejuino, which is made with a base of sourdough corn accompanied by lemon ice cream, or tepache, which is made from the bark of fermented pineapple.

Another typical meal of Guadalajara and the entire state of Jalisco is the "birria", which is usually made with either pork, beef, or goat. Handcrafted birria is made in a special oven, which can be underground and covered with maguey leaves; the meat can be mixed with a tomato broth and spices, or consumed separately.[110] The traditional way of preparing birria is to pit roast the meat and spices wrapped in maguey leaves.[111] It is served in bowls with minced onion, limes and tortillas.

.JPG.webp)

Another typical dish of the tapatía kitchen is the carne en su jugo This dish consists of a beef broth with beans from the pot and is accompanied by bacon, coriander, onion, and radish (sliced or whole). The dessert that is considered as a typical tapatío is the jericalla.

When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Aztec empire, a few religious ceremonies included eating pozole made with hominy and human flesh. This was the first type of pozole mentioned in Spanish writing, as a ritual dish eaten only by select priests and noblemen. The meat from the thighs of slain enemy warriors was used. The Franciscan missionaries ended this custom when they banned Aztec religious ceremonies. The pozole in the local common cuisine was related to the ritual dish, but prepared with turkey meat, and later pork, not with human flesh.[112]

Other dishes that are popular here include pozole, a soup prepared with hominy, pork or chicken, topped with cabbage, radishes, minced onions, and other condiments; pipián, which is a sauce prepared with peanuts, squash and sesame seed, and biónico, a popular local dessert.

Jericallas are a typical Guadalajara dessert that is similar to flan, that was created to give children proper nutrients while being delicious. It is made with eggs, milk, sugar, vanilla, and cinnamon, and baked in the oven where it is broiled to the point that a burnt layer is produced. The burnt layer at the surface is what makes this dessert special and delicious.[113]

One of the drinks that is popular in Guadalajara is Tejuino, a refreshing drink that contains a corn fermented base with sugarcane, lime, salt and chili powder.[114]

The city hosts the Feria Internacional Gastronomía (International Gastronomy Fair) each year in September showcasing Mexican and international cuisines. Many restaurants, bars, bakeries and cafés participate as well as producers of beer, wine and tequila.[110]

Sports

.jpg.webp)

Guadalajara is home to four professional football teams; Guadalajara, also known as Chivas, Atlas, C.D. Oro and Universidad de Guadalajara. Guadalajara is the most followed club in the country,[115] They have won the Mexican Primera División a total of 12 times, and have won the Copa MX four times. In 2017 Chivas became the first team in Mexican football history to win a Double (a league and cup title) in a single season on two different occasions and their first since the 1969–70 season.[116] Chivas went on to win the 2018 CONCACAF Champions League final against Major League Soccer side Toronto FC, the second time they have won the tournament. Chivas won the first ever CONCACAF Champions League and are the only Guadalajara-based football team to win the tournament. Atlas also plays in the Mexican Primera División. They are known in the country as 'The academy', hence they have provided Mexico's finest football players, among them: Rafael Márquez, Oswaldo Sánchez, Pável Pardo, Andrés Guardado, and the Mexican national team's former top scorer Jared Borgetti. Atlas also won several championships in amateur tournaments, and the first championship for a Guadalajaran team in 1951. They won the first division championship again in 2021. Estudiantes was associated with the Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara A.C. It played in the Primera División, with home games in the Estadio 3 de Marzo (March 3 Stadium, for the university's 1935 date of founding). They've won also a single Championship back in 1994 as they defeated Santos. The team moved to Zacatecas and became the Mineros de Zacatecas in May 2014.

Starting in October 2014, Guadalajara rejoined the Liga Mexicana del Pacífico baseball tournament with the Charros de Jalisco franchise in play at the Athletic Stadium. Charreada, the Mexican form of rodeo and closely tied to mariachi music, is popular here. The biggest place for Charreada competitions, the VFG Arena, is located near the Guadalajara Airport founded by singer Vicente Fernández. Every September 15, charros make a parade in the downtown streets to celebrate the Charro and Mariachi Day.[104]

Guadalajara hosted the 2011 Pan American Games.[117] Since winning the bid to host the Games, the city had been undergoing extensive renovations. The games brought in more than 5,000 athletes from approximately 42 countries from the Americas and the Caribbean. Sports included aquatics, football, racquetball, and 27 more, with six others being considered. COPAG (the Organizing Committee for the Pan American Games Guadalajara 2011) had a total budget of US$250 million with the aim of updating the city's sports and general infrastructure. The center of the city was repaved and new hotels were constructed for the approximately 22,000 rooms that were needed in 2011. The new bus rapid transit (BRT) system, Macrobús, was launched in March and runs along Avenida Independencia. The Pan-American village was built around the Bajio Zone. After the Games, the buildings will be used for housing. There are already 13 existing venues in Guadalajara that the games will use, including the Jalisco Stadium, UAG 3 de Marzo Stadium, and the UAG Gymnasium. Eleven new sporting facilities were created for the event. Other works included a second terminal in the airport, a highway to Puerto Vallarta and a bypass for the southern part of the city.[118]

Lorena Ochoa, a now-retired former #1 female golfer, Sergio Pérez who drives for Red Bull Racing F1 Team in Formula One, and Javier "Chicharito" Hernández, a forward who currently plays for LA Galaxy and the Mexico national team were also born in the city.

The city hosted the 2021 WTA Finals, the first time the tournament was played in Latin America.

The city will be one of three cities in Mexico to host matches during the 2026 FIFA World Cup. [119]

Tapatío