Sikh music

Sikh music, also known as Gurbani Sangeet (Gurmukhi: ਗੁਰਬਾਣੀ ਸੰਗੀਤ, romanized: Gurabāṇī sagīta; meaning music of the speech of wisdom), and as Gurmat Sangeet (Gurmukhi: ਗੁਰਮਤਿ ਸੰਗੀਤ, romanized: Guramati sagīta; meaning music of the counsel or tenets of the Guru), or even as Shabad Kirtan (Gurmukhi: ਸ਼ਬਦ ਕੀਰਤਨ, romanized: Śabada kīratana), is the classical music style that is practised within Sikhism.[1] It exists in institutional, popular, and folk traditions, forms, and varieties.[2][3] Three types of Sikh musicians are rababis, ragis, and dhadhis.[1] Sikh music exists in various melodic modes, musical forms, styles, musicians, and performance contexts.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

Terminology

Whilst the term Gurmat Sangeet has come to be used as a name for all Sikh kirtan performed as per the prescribed ragas found within the Sikh scripture, Inderjit Kaur believes a more fitting term for the raga genre is "rāg-ādhārit shabad kīrtan".[1] She further believes that the Sikh musicology as a whole should be referred to as "gurmat sangīt shāstar/vigyān", of which, raga kirtan is a genre found within.[1]

History

Period of the Sikh gurus

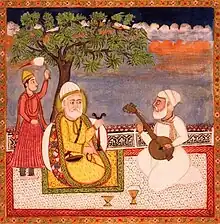

Musical expression has held a very important place within the Sikh tradition ever since its beginning, with Guru Nanak and his faithful companion, Bhai Mardana.[1] Textual traditions connecting Guru Nanak and Mardana to music include the Janamsakhis and the Varan of Bhai Gurdas.[1] There are also artistic depictions of Guru Nanak and Mardana as musicians amid various 18th and 19th century paintings, where Guru Nanak is shown singing whilst Mardana is playing his instrument.[1]

References made to music during the time of Guru Nanak found within the Varan of Bhai Gurdas, includes:[1]

ghar ghar hove dharamsāl, hove kīrtan sadā visoā |

Every house was a place of worship with constant kīrtan as on Baisakhi |

| —Varan Bhai Gurdas 1:27 |

Regarding the Kartarpur chapter of Guru Nanak's life, Bhai Gurdas states:[1]

sodaru ārtī gāvīai amrit vele jāpu uchārā |

Sodar and Ārtī were sung, and in the early morning Jāp was recited |

| —Varan Bhai Gurdas 1:38 |

Mardana was a player of the rabab (plucked lute), and would travel alongside Nanak and play the instrument when Nanak spoke his teachings.[4][1] As a result of this, Mardana is credited as establishing the rababi tradition in Sikhism. When Guru Nanak received a revelation, he would exclaim: "Mardaneya! Rabab chhed, bani aayee hai" ['Mardana, play the rabab, bani (sacred composition/verse) has occurred to me'].[5][1]

After Guru Nanak settled down in the locality he founded, known as Kartarpur, the accompanying verse compositions to the music him and Mardana conjured was recorded in various pothis, of which, the Guru Harsahai Pothi claims to be an extant text of this kind.[1]

During the time of Guru Nanak, the predominant musical tradition of the era was the dhrupad and dhamar, which ended up influencing this early Sikh musical expression.[5] Later, other musical traditions, such as khayal, tappa, and qawwali, began to influence the Sikhs.[5]

After the passing of Guru Nanak, his successors would continue to expand Sikh musicology and add new flavours and colours to it.[1] Guru Angad, the second guru and immediate successor of Nanak, regularized the chanting of the Āsā kī Vār ("Ballad of Hope") composition in the early morning hours as a carol.[1] Angad's successor, Guru Amar Das, institutionalized the practice of ending kirtan performances with the Ānand ("Bliss") composition.[1] As for the next guru, Guru Ram Das regulated the performance of the Lāvāṅ verses as kirtan to form the prime component of Sikh wedding ceremonies.[1]

According to popular Sikh tradition, Guru Arjan was a player of the sarandā (waisted bowed lute) and is also remembered as the inventor of the upright jọṛī (drum pair), which he had derived from an older instrument known as the mridang.[1] Guru Arjan was also the one who compiled the Adi Granth, the first edition of what would become the Guru Granth Sahib later-on, which was and remains the main source for Sikh religious musical theory and practice.[1] Guru Arjan is further credited with establishing the practice of there being five kirtan chaukīs (sittings) at the Harmandir Sahib shrine in Amritsar.[1] The five sittings of kirtan that was established by him are as follows:[1]

- early morning chaukī performance of the Asa ki Var[1]

- mid-morning chaukī performance of the Anand[1]

- mid-day chaukī performance of the Charan Kanwal[1]

- evening chaukī performance of Sodar[1]

- nighttime chaukī performance of Kalyan[1]

In a case of mythology interacting with history, various instruments' origin is credited to Sikh gurus.[5] The taus and dilruba is ultimately of Iranic origins, with the taus designed into a unique peacock shape and introduced into Sikh music by Guru Hargobind and the later dilruba invented by Guru Gobind Singh.[5] The saranda is traced back to Guru Amar Das and Guru Arjun.[5] Furthermore, the Sikh gurus actively patronized and encouraged the musical development of professional kirtan performers.[1]

Post-guru period

.jpg.webp)

The first decline of Sikh musical traditions began following the death of Guru Gobind Singh and execution of Banda Singh Bahadur in the early 18th century.[1] After the death of Banda, the Sikhs had to disperse to places of safe haven during state persecution and thus their established musical institutions could not easily be sustained whilst they were fighting for survival.[1] At many points during the 18th century, no kirtan was being performed at the central Sikh shrine of Harmandir Sahib in Amritsar due to the reigning governments' genocidal policies enacted against the Sikhs.[1] However, later on the same century, Jassa Singh Ahluwalia, who himself was a renowned kirtankar, restarted many Sikh musical traditions that had been on the brink of extinction.[1] The various Sikh states (especially Patiala, Nabha, and Kapurthala) of the 19th century also did their part on ensuring the smooth passing of Sikh musical tradition throughout the generations by patronizing many Sikh musicians.[1]

In the early 19th century, the harmonium began to be used amongst local musicians, eventually including Sikhs, in the Indian subcontinent, its adoption would have devastating impacts on native Sikh instruments.[1] The harmonium was easy to learn and play, plus it was easily transported, which led to it becoming popular and eventually replacing many local Sikh instruments.[1] However, the harmonium is unsuited for playing traditional raga music because of its rigidness, fixed-state, and equal-temperament tuning that cannot create the microtonal inflections and ornaments required within raga music.[1]

Then around the turn of the 20th century, a group of Sikh scholars, namely Charan Singh, Kahn Singh Nabha, and Vir Singh, promoted traditional Sikh music as part of the religious community's "identity, culture, and society."[1] During the partition of Punjab in 1947, one of the three Sikh traditional music institutions, the Rababis, would suffer a deathblow it has not since recovered from, as many former Muslim rababis who had performed at Sikh shrines moved away to Pakistan and future performances by Muslim rababis at Sikh sites was barred by the Sikh clergy due to changing sociocultural norms.[1][5] The Muslim rababis did not have any Sikh patrons in the newly-formed Pakistan, as the local Sikhs also left for India, leaving their traditional art in decline.[1]

_of_Takht_Hazur_Sahib_and_a_court_musician_of_the_Nizam_of_Hyrderabad.jpg.webp)

These reoccuring disturbances also led to the decline of many aspects of Sikh musical tradition.[1] Sikh music performed as per the musical modes, melodies, and forms prescribed as per the Guru Granth Sahib declined greatly.[1] This was accompanied by a decline in the usage of traditional Sikh instruments, especially stringed-instruments (such as the rabab, saranda, and tāūs [bowed fretted lute]) which were mostly supplanted by the introduced harmonium by the early-to-mid-20th century.[1] Additionally in the same time period, traditional drum instruments, such as the mridang and jori, also became scarce amongst the Sikhs, having been replaced by the tablā.[1]

Changes can also be observed regarding the size of kirtan groups who were performing.[1] Before, it was normal for there to be four performers (chaukī, literally, “four”, consisting of a vocalist, supporting vocalist, stringed melodic instrument player, and drummer) but the standard size of a kirtan group performance was reduced to a trio of three persons.[1] This reduction in a role is due to the decline of stringed instruments, as before there was a dedicated stringed-instrumentalist in a kirtan group.[1] Nowadays kirtan groups consist of the two vocalists playing the harmonium alongside a drummer on the tabla.[1]

In recent times, the traditional raga based Sikh musical tradition (including singing the partal with a complex array of taals) has fallen out of favour and been replaced with "semi-classical, light, light, folk or even filmy" styles.[5] However, efforts are being undertaken to revive traditional Sikh raga musical expression.[5] Traditional Sikh instruments have been supplanted by the harmonium, violin, mandolin, and electronic keyboard, and are at risk of extinction.[5]

Revival and documentation of the traditional forms

The first effort to revive the musical traditions of the Sikhs in their autochenous form, incorporating both the historical instruments, metres, and modes, began in the 1930s–'40s by the Sikh Reht Maryada movement.[5] During the 1970s, the Namdhari leader, Jagjit Singh, tried in his own effort to revive the musical traditions of the Sikhs.[5] Many youth were trained in traditional Gurmat Sangeet at Bhaini Sahib through the Namdhari effort.[5] The next push for the revival of Sikh traditional music was in 1991 during the Adutti Gurmat Sangeet Sammellan at Gurdwara Gur Gian Prakash, or the Jawwadi Taksal, in Ludhiana.[5] The Jawwadi Taksal sought to bring back traditional instruments that the harmonium had supplanted and revive the usage of raga metres and modes.[5] In circa 2007, the SGPC made a similar push to resurrect the traditional Sikh instruments and ragas at its gurdwaras but this was a short-lived attempt and was given up on after three or four lessons due to the difficulty of teaching the musical performers the traditional methods and tools.[5] It has been argued by Amandeep Singh (dilruba player) that the harmonium distracts the congregation whilst the traditional instruments help create a meditative experience.[5]

Some scholarly work has been conducted to identify original raga traditions that were invented and performed by the Sikhs.[1] The Punjabi University of Patiala conducted work in 1979 for this purpose, analyzing the musical traditions practiced by the eleventh-generation familial ragi brothers, Gurcharan Singh and Avtar Singh, eventually publishing their study of 500 shabad executions plus the notations by the two brothers under the title Gūrbāni Sangīt: Prāchīn Rīt Ratnāvalī.[1] In 1991, during the traditional Sikh musicology campaign by the Ludhiana Jawaddi Kalan (Sikh school of music), an audio-recording effort of traditional Sikh ragi families' performances, in-order to document and preserve the Sikh music tradition, was overseen by Sant Succha Singh.[1] A committee was formed for the purpose of identifying the authentic Sikh raga traditions and renditions of various raga types, known as the Rag Nirnayak Committee.[1] The findings of the committee were commended upon by Gurnam Singh in 2000.[1] A later and updated edition of the Gūrbāni Sangīt: Prāchīn Rīt Ratnāvalī provides the views of the late Bhai Avtar Singh Ragi on the subject of autochenous Sikh raga traditions and styles.[1] Greater investigation is needed to look at the issue in further-depth, such as viewing the diverse rag-form and notation material, and also the identification of different rag versions with different taksāls (schools of music).[1] Inderjit Kaur's research on ghar variants of different ragas links the usage of many of them to the Sikh gurus, which could legitimize their usage in contemporary Sikh musical performances.[1]

Sources

The Adi Granth compiled by Guru Arjan and completed in 1604 included musical verses from fifteen bhagat saints who belonged to varying religious backgrounds, along with his own works and that of his predecessory gurus.[1] The second edition of the Adi Granth was completed by Guru Gobind Singh, whom added the works of his father, the previous guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur.[1] It is the second edition of the text that was renamed as the Guru Granth Sahib and given the mantle of being the guru of the Sikhs.[1] Sikh musical tradition derives mostly from this scripture.[1]

Traditional Sikh kirtan only sings verses sourced from either the Guru Granth Sahib, the Dasam Granth, the Varan of Bhai Gurdas, or the Ghazals of Bhai Nand Lal.[1] No other literary work is allowed to be a source for Sikh religious kirtan.[1] However, an exception exists for the dhadi tradition, which sing heroic ballads not sourced from the above texts.[1]

Guru Granth Sahib

The central Sikh sacred text, the Guru Granth Sahib, contains 6,000 shabads, with most of them arranged methodically to music and authorship by their title, known as the sirlekh.[1] Within the shabads, there are musical notations contained within them, known as rahāu (chorus) and ank (verse).[1] The text itself provides the structure of the metre and rāg-dhyān shabads provide information on the aesthetics of the music.[1]

Sirlekh

Sirlekh refers to the shabad titles and important information regarding music is expressed within it.[1] Firstly, the type of rāg, a musical designation within the Indian melodic system, is given.[1] Secondly, various kinds of musical forms, such as pade, chhant, vār, ghōṛīān, and more, may also be expressed within the title.[1] However, the true contents and meanings of these musical forms have mostly been lost to common knowledge and are now unknown.[1] Finally, the final important piece of musical information provided in the title is the ghar (literally, “house”), differentiated by various accompanying numbers, whose meanings have also become lost.[1]

Hymn body

Musical information is also expressed within the body of the hymns themselves, examples include the verse meter (tāl), chorus and verse marking and sequencing (rahāu), and aesthetic experience (ras).[1]

Traditional institutions

Rababi tradition

_titled_'Lute_Players_Near_the_Golden_Temple'%252C_taken_on_28_January_1903.jpg.webp)

The musical lineage of Bhai Mardana continued after Mardana's death and his descendents carried-on with serving the Sikh gurus as musical performers.[1] Some examples of descendents of Bhai Mardana who worked as musicians in the durbar (court) of the Sikh gurus include:[1]

- Sajada, whom served Guru Angad at Khadur[1]

- Sadu and Badu, both of whom served Guru Amar Das in Goindwal and Guru Ram Das in Chak Ram Das Pura[1]

- Balvand and Satta, both of whom served both Guru Ram Das and Guru Arjan[1]

- Babak, who served Guru Hargobind[1]

- Chatra, who served the later gurus[1]

The rababi tradition formed out of the lineage of Muslim musicians and instrumentalists performing kirtan for the Sikh gurus and the Sikh community.[1] These Muslim rababis of kirtan were called Bābe ke by the Sikhs, which meant "those of Baba Nanak".[1] A later Muslim rababi who performed kirtan at Sikh shrines, including the Harmandir Sahib, was Bhai Sain Ditta, who flourished during the early part of the 19th century.[1] During this era, the Muslim rababi institution received patronage from various Sikh polities, such as Nabha, Patiala, and Kapurthala states.[1] During the early 20th century, Muslim rababis who regularly performed at the Golden Temple were Bhai Chand, Bhai Taba, and Bhai Lal.[1] By the 20th century, many rababis replaced their traditional rabab by swapping it out with the harmonium.[1]

A blowback to the rabab instrument's usage in Sikh circles came in the aftermath of the partition of the Punjab in 1947, due to many Muslim rababi families migrating to their new homes in Pakistan or became pushed to the margins of society due to changing socio-cultural norms.[5][1] The rabab was gradually replaced by the sarod, another stringed instrument, in Sikh musical circles.[5][1] There have been attempts at reviving the rababi tradition, as there still remains descendents of traditional rababi families living.[1]

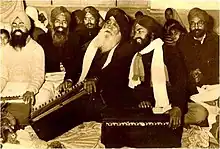

Kirtankar (Ragi) tradition

%252C_ca.1920.jpg.webp)

Developing alongside the Rababi tradition discussed earlier as a parallel tradition were the kīrtankārs, who were Sikh kirtan singers.[1] The institution was born out of a few amateur or non-professional singers during the period of the Sikh gurus.[1] As time went-on, this amateur trend of Sikh singers eventually developed into the professional tradition now known as rāgīs.[1]

Some notable Sikh kirtankars during the period of the Sikh gurus include:[1]

- Dipa and Bula, both of whom served Guru Angad[1]

- Narain Das, Padha, and Ugrsain, all three of whom served Guru Amar Das[1]

- Ramu, Jhaju, and Mukand, all three of whom served Guru Arjan[1]

- Banvali and Parsram, both of whom served Guru Hargobind[1]

- Gulab Rai, Bhel, Mansud, and Gurbaksh, all four of whom served Guru Tegh Bahadur[1]

A renowned ragi or kirtankar during the reign of Maharaja Ranjit Singh's Sikh Empire was Bhai Mansa Singh, who performed at the Golden Temple.[1] Similar to the rababi tradition, the ragi tradition also received the patronage of Sikh polities, such as by Nabha, Patiala, and Kapurthala.[1] One notable ragi who received the sponsorship of Sikh states was Baba Pushkara Singh.[1] Bhai Sham Singh is renowned for his long service as a ragi at the Golden Temple, serving as a kirtan performer for some 70 years around the later 19th and early 20th century.[1] Notable ragis of the early 20th century include Hira Singh, Santa Singh, Sunder Singh, Sammund Singh, Surjan Singh, and Gopal Singh.[1] Later on in the same century, names of ragis like Bhai Jwala Singh (a tenth generation member of a traditional kirtankar family), his sons Avtar Singh and Gurcharan Singh, are important to note.[1] Furthermore, Balbir Singh and Dyal Singh should also be mentioned.[1]

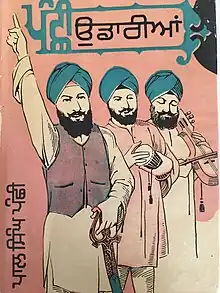

Dhadi tradition

The ḍhāḍī tradition dates back to the time of Guru Hargobind.[1] These dhadi performers sang odes of valour, such as heroic ballads (vaars).[1] Two dhadi performers known by name during the period of the sixth guru are Bhai Abdallah, who played the sārangī, and Bhai Nath, who played the ḍhaḍḍ (small handheld drum).[1] The vogue of the Dhadi tradition rose quickly during this period.[1] Dhadis usually perform in groups of three, where heroic ballads are musically performed but "interspersed with chanted narratives."[1] The overall tone of a dhadi performance tends to be highly charged and is full of emotions.[1] However, the source for the hymns they sing are not sourced from the sanctified works of literature, so the musical performances of dhadis is not classified as "Sikh shabad kirtan" but it still forms a vital and important part of Sikh musicology.[1] A further difference between dhadi performers and other Sikh music traditions is that the dhadis perform whilst standing up, meanwhile the other Sikh musician types perform whilst sitting down.[1]

Forms

There are various genres, contexts, and musicians of modern Sikh music.[1]

Professional

Professional Sikh musical performances are usually done within gurdwaras.[1] Within the central room, there is a dedicated space beside the sacred scripture for the rāgī jathā (ragi ensemble) on an elevated stage.[1] The ragis sit on the elevated stage facing the gathered Sikh congregation in the room, who sit directly on the floor at a lower level.[1] Kirtan is performed within the gurdwaras on both regular and celebatory days.[1] For the major and popular gurdwaras, Sunday (Aitavāra) tends to be the day where more kirtan performances are held throughout the day whilst for other days, kirtan performances usually occur in the evening time.[1]

Kirtan within gurdwara is usually performed by the ragi jathi, typically consisting of three members in modern-times but four members in historical-times.[1] Aside from being required to perform musically, they also are needed to perform the liturgy services.[1] The ragis are traditionally all male and are given the honourifical prefix of Bhāī (literally, "brother").[1] In modern-times, there has been a rise of female ragi jathas, whose members are given the honourifical prefix of Bībī (literally, "lady").[1] Mixed-gender ragi jathas are exceedingly rare.[1] Ragis are not allowed to use caste-based surnames and thus only keep the names 'Singh' and 'Kaur' as a surname, some may further add the word 'Khalsa' to their name.[1] However, it is acceptable for ragis to attach a location-based or employment-based suffix to their name for disambiguation purposes, such as Dilli Vale ("from Delhi") or Hazuri Ragi Harmandir Sahib ("ragi in service at the Harmandir Sahib gurdwara").[1] The ragi jatha members tend to wear simplistic clothes, usually white or off-white long shirts and pants.[1] Ragi males tend to wear white, navy, saffron, or black turbans and female ragis wear long scarves (chunnī).[1] Younger ragis have started wearing different colours outside of traditional range.[1] Ragis are paid a regular salary whilst employed at a gurdwara but they can also perform at private events for extra income.[1] Ragi jathas performing at a ticketed venue is taboo.[1]

What is now termed "traditional" (but it is not truly historically accurate to apply this appellation to this type as truly traditional kirtan differs substantially from what is described here) ragi jatha kirtan performances in gurdwaras nowadays employ simple melodies which are set to basic varieties of tāl—usually the 8-beat kahirvā but also the 6-beat dādrā.[1] The performance of gurbani kirtan within gurdwaras was simplified to allow for the gathered congregation (sadh sangat) to be able to follow along and sing with the performers, it also allows for the laypersons to internalize the message of the underlying hymn rather than focus too much on the musical expression itself.[1] The singing by vocalists is interspersed by supportive and harmonizing melodies played by the harmonium, with the drummer playing variations utilizing the tabla in "tempo and rhythmic variety".[1] All these factors are geared towards producing a calm and spiritual setting and experience for the participants.[1] Presentation and performance are the two important factors of the "traditional" ragi kirtan performance type.[1] Lines from certain hymns tend to be repeated to allow for the listeners to join in on the singing.[1] Various genres found within the "traditional" ragi kirtan sub-type are gīt, ghazal, and bhajan.[1] The most renowned and well-received performer of the "traditional" ragi kirtan style is Bhai Harjinder Singh Srinagar Vale.[1]

However, the truly traditional ragi kirtan style, as found in earlier times, employed stringed instruments rather than the now commonplace harmonium.[1] It also involved more ragas in its performances.[1] Traditional Sikhs attempting to revive the more historical expressions of their music, such as by playing instruments like the rabab, saranda, and taus, are referred to as the gurmat sangīt genre of kirtan.[1] It is largely based upon the contemporary khyāl style of Hindustani classical music.[1]

There are two different kinds of shabad kirtan performances by ragi jathas:[1]

- Parmāṇ-style kirtan - characterized by the ragi interspersing verses from related hymns to elaborate on the main, overarching theme.[1]

- Viākhiā-style kirtan - characterized by the ragi pausing the singing to elaborate on the hymn being performed and present a short discourse or exposition.[1]

There now exists various Sikh educational institutions solely dedicated to teaching Sikh music, that specialize in the training of ragis.[1] However, traditionally the training of ragis occurred at more general Sikh educational institutions (known as a ṭaksāl), which had a section dedicated for the training of Sikh musicians, such as at the Damdami Taksal near Amritsar or Jawaddi Kalan in Ludhiana.[1] Training of Sikh kirtanis usually starts when they are young and aside from their musical training, they are also educated in the Sikh scriptures and correct pronunciation of their contents (known as santhiya).[1] True mastery of kirtan requires a deep understanding and knowledge of Sikh philosophy, history, and culture.[1] According to the late Bhai Avtar Singh, a preeminent ragi of his time, the most important criteria for becoming a good kirtankar was first living a life in-line with the principles set-out in the Guru Granth Sahib, and then an education in its prescribed ragas.[1]

During morning hours, the first chaukī (sitting) consists of a performance of the Āsā kī Vār, which is described as being the most explicitly-defined and unique of all the kirtan sittings, with the utilization of standardized melodies that date back to the time period of the Sikh gurus.[1] One of the unique aspects of this sitting is that it is the only one where the drummer role within a kirtan group is required to sing certain verses solo.[1] In-between the verses of the Asa ki Vaar, the kirtan group can implement verses from other compositions of their liking.[1] No discourse occurs during this sitting and its time length is usually between two and three hours but it may be longer depending on how many other compositions were included to be interspersed between the hymns of the Asa ki Vaar.[1] Kirtanis aim to be able to perform this specific sitting well as it is a badge of honour to be considered a talented performer of it.[1] It is also said to be the sitting that is most inductive of producing a meditative experience for the participants, due to the combination of the early morning hours (amritvela), uninterrupted performance, and long lengths.[1] In-regards to the other sittings, they tend to be much less structured and varied.[1] The other sittings usually consist of the performance of a few gurbani compositions and the performance draws to a close by singing the six stanzas of the Anand composition.[1] The Āratī composition is performed during evening sittings.[1] Another kind of session is known as Raiṇ sabāī (all night), which occur annually as events with various musicians taking part and ending with a Asa ki Vaar performance in the early morning-time.[1] At the principle Sikh shrine, the Harmandir Sahib, kirtani sittings occur continuously all-day and all-night, from the beginning of dawn to past midnight, and are arranged based upon the time of day and season.[1]

During major life events (sanskaras), such as birth (naam karan), death (antam sanskar), marriage (anand karaj), and other ceremonies, kirtan performances are also held.[1] The families celebrating these events can request particular hymns or compositions of their choosing to be sung and played by the kirtani group.[1] With the Anand Karaj specifically, there is a particular arrangement to be followed.[1] First, a group of compositions appropriate to the setting is performed.[1] After, the shabad palai taiḍ ai lāgī (“connected to You”) is performed.[1] Then the four verses of the Lāvān composition are performed.[1] The last hymn performed is the viāh hoā mere bāblā (“the wedding has occurred, O Father”).[1]

Amateur

.jpg.webp)

Amateur expressions of Sikh music tends to rely upon more participation from the general Sikh laity.[1] Instruments used in this form are often hand-held idiophonic percussion instruments, such as the chhaiṇā, chimṭā, and khaṛtāl.[1] The manner of display of amateur forms of Sikh music often is in-contrast to the professional forms.[1] Amateur performances of Sikh music tends to occur as part of a Nagar Kirtan procession on-foot, which occurs outside of gurdwaras' central darbar (court) hall, typically happening around the gurdwara complex or the local neighbourhood, where participation by the general Sikh public in singing the hymns as part of the ceremony is highly encouraged.[1] The leader of the Nagar Kirtan procession gives out a call and the accompanying or observing sangat (congregation) reply with a response.[1] Nagar Kirtans are characterized by their usage of handheld percussion instruments and a dhol secured over the shoulder by its player.[1] Melodic instruments are not used during the procession due to their weight and immobility.[1] However, many modern Nagar Kirtans have floats which allow a ragi jatha to be seated upon to play melodic instruments or simply opt to playing a pre-recording of Sikh music for the event.[1]

Some displays of amateur Sikh music have qawwālī-like characteristics, with a notable genre sharing features with the aforementioned being the Akhanḍ Kīrtanī style.[1] The Akhand Kirtani style began in the early 20th century and was invented by the famous Randhir Singh of the Akhand Kirtani Jatha.[1] The Akhand Kirtani style is distinguished by there being no pauses (which gives rise to its naming from the word akhanḍ, literally "unbroken") between hymns and compositions being performed, with the person leading the performance being a shared role that involves taking turns between men or women in the congregation.[1] The goal of the Akhand Kirtani style is to ignite a "ecstatic fervor" amid members of the participating assembly, which is accomplished by sudden or gradual changes in tempo, rhythm, or volume.[1] This style often involves the recitation and performance of group chantings of Naam Japna, where the most-common name of God in Sikhism, Waheguru, is recited over-and-over again with increasing energy.[1] The style is further characterized by a cyclical pattern of increasing intensity.[1]

Another tradition of amateur Sikh musical performance is the Istrī satsang, which involves Sikh women and girls convening together in gurdwaras during off-peak hours, often in the afternoon.[1] It is characterized by a call-and-response format alternating between various members of the gathered group.[1] An instrument often played during these group musical performances by women is the ḍholkī (small, double-headed barrel) folk-instrument.[1]

Recordings

Many Sikh homes have recorded Sikh music playing throughout the day.[1] Its purpose is to create a setting of serenity and spirituality within the home.[1] Sikhs opt to listen to this form of music when commuting.[1] The recording of Sikh music has grown into a large industry in its own right, which influences how people engage with it, including musical performers and their listeners.[1] The manner of Sikh music recorded within the industry has diverged quite far from how Sikh music was traditionally performed.[1] It is characterized by influences and adoptions of prevailing and popular tunes, trends, styles, and intricate instrumental accompaniment not observable in Sikh musical performances at gurdwaras.[1] Accompanying video records of the music records tend to display the typical ragi jatha trio with two harmonium-players and a tabla-player, with the supporting instruments and musicians invisible in the background not-in-view also playing along to produce the recording.[1]

Musical fundamentals

Raag

| Part of a series on the |

| Guru Granth Sahib ਗੁਰੂ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ਸਾਹਿਬ |

|---|

_beautifully_decorated_with_gold_and_floral_arabesques_01.jpg.webp) |

| Popular compositions |

| Other compositions |

| Various aspects |

| Poetical metres, modes, measures, and rhythms |

A raga or raag (Punjabi: ਰਾਗ (Gurmukhi) رَاگَ (Shahmukhi); Rāg) is a complex structure of musical melody used in Indian classical music and is the central native organizing and classification mechanism and scheme present within the Guru Granth Sahib, where various compositions and sections of the text are privided primarily based upon their accompanying rāg.[1] It is a set of rules of how to build a melody which can ignite a certain mood in the reciter and listeners. There are primarily 31 ragas utilized within the primary Sikh scripture, with further variants ragas based upon these primary set.[1] Whilst a lot of the variant ragas have been given names, many are instead named based upon sequential ghar numbers.[1] An exception of this is the Gauṛī primary raga, whose variants have been given their own dedicated names.[1]

The primary ragas, their derivative versions (along with assigned ghars) are:[1]

- Srīrāg, with seven variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-7[1]

- Mājh, with four variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-4[1]

- Gauṛī Guārerī, with eleven variants, designated with names (without any ghar number designations): Gauṛī Guārerī, Gauṛī Dakhaṇī, Gauṛī Chetī, Gauṛī Bairāgaṇ, Gauṛī Pūrbī-Dīpkī, Gauṛī Pūrbī, Gauṛī Mājh, Gauṛī Mālvā, Gauṛī Mālā, and Gauṛī Soraṭh[1]

- Āsā, with seventeen variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-17, three of which have names: Āsā Kāfī (ghar 8), Āsāvarī Sudhang (ghar 16), and Āsā Āsāvarī (ghar 17)[1]

- Gūjrī, with four variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-4[1]

- Devgandhārī, with seven variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-7[1]

- Bihāgṛā, with two variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-2[1]

- Vaḍhans, with five variants: Vaḍhans Dakhaṇī, and others designated with ghar numbers 1, 2, 4, and 5[1]

- Soraṭh, with four variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-4[1]

- Dhanāsrī, with ten variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-9 and 12[1]

- Jaitsrī, with four variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-4[1]

- Ṭōḍī, with five variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-5[1]

- Bairārī, with one variant, designated with ghar number 1[1]

- Tilang, with four variants: Tilang Kāfī, and others designated with ghar numbers 1-3[1]

- Sūhī, with ten variants: Sūhī Lalit, and others designated with ghar numbers 1-7 and 9, and 10 named as Sūhi Kāfī[1]

- Bilāval, with fifteen variants: Bilāval Dakhaṇī, Bilāval Mangal, and others designated with ghar numbers 1-13[1]

- Gonḍ, with three variants: Bilāval Gonḍ, and others designated with ghar numbers 1-2[1]

- Rāmkalī, with four variants: Rāmkalī Dakhaṇī, and others designated with ghar numbers 1-3[1]

- Naṭ Nārāin, with one variant without a ghar number designation[1]

- Mālī Gauṛā, with one variant without a ghar number designation[1]

- Mārū, with nine variants: Mārū Dakhaṇī, and others designated with ghar numbers 1-8 with ghar 2 named as Māru Kāfī[1]

- Tukhārī, with one variant without a ghar number designation[1]

- Kedārā, with five variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-5[1]

- Bhairau, with three variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-3[1]

- Basant, with two variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-2, with ghar 2 named as Basant Hindol[1]

- Sārang, with six variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-6[1]

- Malār, with three variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-3[1]

- Kānaṛā, with eleven variants, designated with ghar numbers 1-11[1]

- Kaliān, with three variants: Kaliān Bhopālī, and others designated with ghar numbers 1-2[1]

- Prabhātī Bibhās, with four variants: two versions of Prabhātī Bibhās, designated with ghar numbers 1 -2, and Prabhātī Dakhaṇī and Bibhās Prabhātī[1]

- Jaijāvantī, with one variant without a ghar number designation[1]

The Sikh holy scripture, Guru Granth Sahib, is composed in and divided into a total of 60 ragas.[6] This is a combination of 31 single raags [7] and 29 mixed (or mishrit; ਮਿਸ਼ਰਤ) raags (a raag composed by combining two or three raags together). Each raga is a chapter or section in the Guru Granth Sahib starting with Asaa raag, and all the hymns produced in Asaa raag are found in this section ordered chronologically by the Guru or other Bhagat that have written hymns in that raga. All raags in the Guru Granth Sahib Ji are named raag.

Sikhs ragas were both sourced from ragas used within both Hindu and Islamic music.[1] For example, Bhairav and Srirag ragas are Hindu liturgical ragas whilst Suhi raga and the Kafi styles were from the Sufi tradition.[1] Further, some of the ragas were sourced from folk culture and traditions, such as the Asa and Majh ragas.[1] The names of variations of the ragas also detail that various regional styles that influenced them.[1] The variations of the Gauri raga reveal different regional locations.[1] The organization of the various ragas within the Guru Granth Sahib is a contested topic of debate amongst the academe, with different scholars offering their views.[1]

Gurinder Singh Mann states the following, highlighting the unknown that remains when attempting the understand the organization of the Guru Granth Sahib:[1]

[T]he rāg arrangement in the Adi Granth, unlike that in the Goindval Pothis, defies an entirely satisfactory explanation... My suggestions toward interpreting the structure of the Adi Granth may yet yield no perfect answers, but I hope they are sufficient to challenge any argument that the rag combinations of the Adi Granth are insignificant.

— Gurinder Singh Mann, The Making of Sikh Scripture (2001), page 94

Pashaura Singh also offered his views on the topic, believing that using modern Indic musical traditions to analyze the musical system of the Guru Granth Sahib is insufficient:[1]

[T]he raga organization of the Adi Granth presents an excellent combination of lyrical and rational elements. It is far more complex than any simple explanation would describe it. It may be added here that understanding the ragas of the Adi Granth and their organization solely in terms of the modern Indian musical tradition is inadequate.

— Pashaura Singh, The Guru Granth Sahib: Canon, Meaning and Authority (2000), page 149

Before the compilation of the Adi Granth, there were various pothīs (manuscripts) circulating around the contemporary Sikh circles, with the most well-known of them being the Goindwal Pothis.[1] The Goindwal Pothis contain musical information based upon ragas.[1] The musical raga expression of the pothis during the period of the early Sikh gurus were mostly stable throughout the years but the changes that are observed across the various texts reflect wider changes of Indian raga music during the time-periods they were compiled, such as the invention of new ragas and new forms of existing ragas.[1] Particular ragas were selected or invented by the Sikh gurus for their purported spiritual effects and their ability to evoke the state of ras.[1] The Guru Granth Sahib states:[1]

ਧੰਨੁ ਸੁ ਰਾਗ ਸੁਰੰਗੜੇ ਆਲਾਪਤ ਸਭ ਤਿਖ ਜਾਇ ॥ |

Blessed are those beautiful rāgs which, when chanted, eliminate all desire. |

| —Guru Granth Sahib, page 958 |

Following is the list of all sixty raags (including 39 main raags and 21 mishrit [mixed] raags, including Deccani ones) under which Gurbani is written, in order of appearance with page numbers. The name of raags ending with the word Dakhani (English: Deccani) are not mishrit raags because Dakhani is not a raag per se; it simply means 'in south Indian style'.

| No. | Name(s) (Latin/Roman) | Name(s) (Gurmukhi) | Emotion/Description[8] | Ang (page of appearance in Guru Granth Sahib) | Main, Mixed, or Deccani |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Asa/Aasa | ਆਸਾ | Making effort | 8 | Main |

| 2. | Gujari/Gujri | ਗੂਜਰੀ | Satisfaction, softness of heart, sadness | 10 | Main |

| 3. | Gauri Deepaki | 12 | Mixed | ||

| 4. | Dhanasri/Dhanasari | ਧਨਾਸਰੀ | Inspiration, motivation | 13 | Main |

| 5. | Gauri Poorabi | 13 | Mixed | ||

| 6. | Sri/Siri | ਸਿਰੀ/ਸ੍ਰੀ | Satisfaction and balance | 14 | Main |

| 7. | Majh/Maajh | ਮਾਝ | Loss, beautification | 94 | Main |

| 8. | Gauri Guarairee | 151 | Mixed | ||

| 9. | Gauri | ਗਉੜੀ | Seriousness | 151 | Main |

| 10. | Gauri Dakhani | 152 | Deccani | ||

| 11. | Gauri Chaitee | 154 | Mixed | ||

| 12. | Gauri Bairagan | 156 | Mixed | ||

| 13. | Gauri Poorabi Deepaki | 157 | Mixed | ||

| 14. | Gauri Majh | 172 | Mixed | ||

| 15. | Gauri Malva | 214 | Mixed | ||

| 16. | Gauri Mala | 214 | Mixed | ||

| 17. | Gauri Sorath | 330 | Mixed | ||

| 18. | Asa Kafi | 365 | Mixed | ||

| 19. | Asavari | 369 | Mixed | ||

| 20. | Asavari Sudhang/Komal Rishabh Asavari | 369 | Mixed | ||

| 21. | Devgandhari | ਦੇਵਗੰਧਾਰੀ | No specific feeling but the Raag has a softness | 527 | Main |

| 22. | Bihagra/Bihaagra | ਬਿਹਾਗੜਾ | Beautification | 537 | Main |

| 23. | Vadhans/Vadahans/Wadhans | ਵਡਹੰਸੁ | Vairaag, loss (that is why Alahniya is sung in this Raag when someone passes away) | 557 | Main |

| 24. | Vadhans Dakhani | 580 | Deccani | ||

| 25. | Sorath | ਸੋਰਠਿ | Motivation | 595 | Main |

| 26. | Jaitsri/Jaitsari | ਜੈਤਸਰੀ | Softness, satisfaction, sadness | 696 | Main |

| 27. | Todi | ਟੋਡੀ | This being a flexible Raag it is apt for communicating many feelings | 711 | Main |

| 28. | Bairarri/Bhairaagi | ਬੈਰਾੜੀ | Sadness (the Gurus have, however, used it for the message of Bhakti) | 719 | Main |

| 29. | Tilang | ਤਿਲੰਗ | Favoured Raag of Muslims. It denotes feeling of beautification and yearning | 721 | Main |

| 30. | Tilang Kafi | 726 | Mixed | ||

| 31. | Suhee/Soohi/Suhi | ਸੂਹੀ | Joy and separation | 728 | Main |

| 32. | Suhee Kafi | 751 | Mixed | ||

| 33. | Suhee Lalit | 793 | Mixed | ||

| 34. | Bilaval/Bilaaval | ਬਿਲਾਵਲ | Happiness | 795 | Main |

| 35. | Bilaval Dakhani | 843 | Deccani | ||

| 36. | Gound/Gond/Gaund | ਗੋਂਡ | Strangeness, surprise, beauty | 859 | Main |

| 37. | Bilaval Gound | 874 | Mixed | ||

| 38. | Ramkali/Raamkali | ਰਾਮਕਲੀ | Calmness | 876 | Main |

| 39. | Ramkali Dakhani | 907 | Deccani | ||

| 40. | Nut Narayan/Nat Narayan | ਨਟ ਨਾਰਾਇਨ | Happiness | 975 | |

| 41. | Nut/Nat | ਨਟ | 975 | ||

| 42. | Mali Gaura/Maali Gaura | ਮਾਲੀ ਗਉੜਾ | Happiness | 984 | Main |

| 43. | Maru/Maaru | ਮਾਰੂ | Giving up of cowardice | 989 | Main |

| 44. | Maru Kafi | 1014 | Mixed | ||

| 45. | Maru Dakhani | 1033 | Deccani | ||

| 46. | Tukhari | ਤੁਖਾਰੀ | Beautification | 1107 | Main |

| 47. | Kedara | ਕੇਦਾਰਾ | Love and beautification | 1118 | Main |

| 48. | Bhairo/Bhairao/Bhairon | ਭੇਰੳ | Seriousness, brings stability of mind | 1125 | Main |

| 49. | Basant | ਬਸੰਤੁ | Happiness | 1168 | Main |

| 50. | Basant Hindol | 1170 | Mixed | ||

| 51. | Sarang | ਸਾਰੰਗ | Sadness | 1197 | Main |

| 52. | Malar/Malaar/Mallar/Malhar | ਮਲਾਰ | Separation | 1254 | Main |

| 53. | Kanra/Kaanrha | ਕਾਨੜਾ | Bhakti and seriousness | 1294 | Main |

| 54. | Kaliyan/Kaliaan/Kalyan | ਕਲਿਆਨ | Bhakti Ras (meaning 'devotional spirit/essence') | 1319 | Main |

| 55. | Kaliyan Bhopali | 1321 | Mixed | ||

| 56. | Parbhati Bibhas | 1327 | Mixed | ||

| 57. | Parbhati/Prabhati | ਪ੍ਰਭਾਤੀ | Bhakti and seriousness | 1327 | Main |

| 58. | Parbhati Dakhani | 1344 | Deccani | ||

| 59. | Bibhas Parbhati | 1347 | Mixed | ||

| 60. | Jaijavanti/Jaijaiwanti | ਜੈਜਾਵੰਤੀ | Viraag or loss | 1352 | Main |

Raags are used in Sikh music simply to create a mood, and are not restricted to particular times. A mood can be created by the music of the raag regardless of the time of day. There are a total of 60 raags or melodies within the Guru Granth Sahib. Each melody sets a particular mood for the hymn, adding a deeper dimension to it. The Guru Granth Sahib is thought by many to have just 31 raags or melodies which is correct of single raags. However, combined with mishrit raags, that total is 60.

Ghar

%252C_from_a_series_of_painting_of_the_first_nine_Sikh_gurus%252C_circa_1800%E2%80%931840.jpg.webp)

Many of the raga and musical form sections found within the Guru Granth Sahib have been allotted corresponding ghars as a numeric designation, with most having up to seven ghar forms assigned to them.[1] However, the inner meaning of these ghar designations are accepted to have been lost throughout the centuries.[1] Due to this, it is not utilized within contemporary Sikh music.[1]

After analyzing the titles of the ghars found in the Gauri raga titles and their lack of numeric designations, Inderjit Kaur believes the ghars correspond to varying versions of particular ragas.[1] Another view is that the ghars are related to the tāl (meter) and shrutī (microtone).[1] However an argument is made against its relation to shrutīs based upon the observation that sequential shrutīs cannot occur in ragas which are not heptatonic.[1]

The table below covers the seventeen Ghars found in the primary Sikh scripture (Guru Granth Sahib):[9]

| No. | Name(s) (Latin/Roman) | Taalee(s) (Pattern of Clapping) | Maatraa(s) (Beat) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Daadraa Taal | 1 | 6 |

| 2. | Roopak Taal | 2 | 7 |

| 3. | Teen Taal | 3 | 16 |

| 4. | Chaar Taal | 4 | 12 |

| 5. | Panj Taal Swaaree | 5 | 15 |

| 6. | Khatt Taal | 6 | 18 |

| 7. | Matt (Ashat) Taal | 7 | 21 |

| 8. | Asht Mangal Taal | 8 | 22 |

| 9. | Mohinee Taal | 9 | 23 |

| 10. | Braham Taal | 10 | 28 |

| 11. | Rudra Taal | 11 | 32 |

| 12. | Vishnu Taal | 12 | 36 |

| 13. | Muchkund Taal | 13 | 34 |

| 14. | Mahashanee Taal | 14 | 42 |

| 15. | Mishr Baran Taal | 15 | 47 |

| 16. | Kul Taal | 16 | 42 |

| 17. | Characharee Taal | 17 | 40 |

Taal

Taals have a vocalised and therefore recordable form wherein individual beats are expressed as phonetic representations of various strokes played upon the tabla. Various Ghars (literally 'Houses' which can be inferred to be "styles" – basically styles of the same art with cultivated traditional variances) also have their own preferences.[10] The term "tāl" is not explicitly used within any shabad title, aside from the paṛtāl form.[1]

Musical forms

Within the Guru Granth Sahib, various musical forms are utilized.[1] A list of Sikh musical forms are listed below:[1]

- Pade (songs with chorus and verse)[1]

- Vār (ballad)[1]

- Chhand (metered verse)[1]

- Paṛtāl (verse with metrical variation)[1]

- Bārahmāh (song of the twelve months)[1]

- Thitī (song of lunar dates)[1]

- Pahre (songs of the times of the day)[1]

- Birahaṛe (songs of separation)[1]

- Paṭī and Bāvaṇ Akharī (acrostic song using letters of the Gurmukhi alphabet)[1]

- Ghoṛīāṅ (wedding songs)[1]

- Alāhṇīāṅ (songs of death)[1]

- Āratī (song honoring divinity)[1]

- Rutī (song of seasons)[1]

- Salok (couplets)[1]

- Sadu (invocation)[1]

- Sohilā (song of praise)[1]

Most hymns contained within the Guru Granth Sahib are in the Pade form, which was a popular form within the prevailing Indian music between the 16th and 17th centuries.[1] During the time period when Sikh hymns were composed, the dhrupad form was popular in northern Indian mandirs whilst the kritī form dominated in south Indian mandirs.[1] However, neither of these forms are present within the Sikh scripture.[1]

Melody specifications

There are various melody specifications used within the Guru Granth Sahib, known as dhunī.[1] These particular melodies are assigned mostly to the hymns falling under the vaar form and were based upon popular, contemporary melodies.[1]

Chorus and verse marking and sequencing

Within a particular shabad hymn found in the scripture, choruses are marked with a rahāu (literally, "pause") designation whilst verses are marked with ank.[1] It is akin to the ṭek (literally, "support") marker used in other Indic musical traditions.[1] The verse containing a rahāu marker are often the ones that communicate the central message of the particular hymn.[1] The majority of hymns contain a rahāu marker after the first verse, which is termed as rahāu-subsequent.[1] However, there are also hymns that contain a rahāu marker at the antecedent position and further there also exist hymns which are absent of these markers.[1] There also exist two rahāu markers within the same hymn, usually the first marker occurs after a verse in question form and the second marker exists after the verse in answer form to the prior question presented earlier in the hymn.[1] There are also numeric sequencing markers to formulate the order at-which verses are to be followed when being performed.[1]

Aesthetic experience

The concept of the hymns within the text producing a specific emotional and psychological reaction or state upon the listener or performer is known as ras (aesthetic experiences).[1] Hymns aiming to evoke the state of bhaktī ras (devotion) will be overlaid with themes of "love, longing, union, wonder, and virtue."[1] Some other ras' are ānand (bliss) ras, amrit (nectar) ras, har (divine) ras, and nām (name) ras.[1] Within this concept, there are three prevailing categories known as shabad surat (shabad-attuned consciousness), sahaj dhyān (serene contemplation), and har ras (beyond other aesthetic delights).[1]

Instruments

Sikhs have historically used a variety of instruments (Gurmukhi: ਸਾਜ Sāja) to play & sing the Gurbani in the specified Raag. The Sikh Gurus specifically promoted the stringed instruments for playing their compositions. Colonization of the Indian Subcontinent by the British Empire caused the use of traditional instruments (ਤੰਤੀ ਸਾਜ; tanti sāja meaning "stringed instruments")[11] to die down in favor of foreign instruments like the harmonium (vaaja; ਵਾਜਾ).[12] There is now a revival among the Sikh community to bring native, Guru-designated instruments back into the sphere of Sikh music to play Gurbani in the specified Raag.[13] Organizations like Raj Academy & Nad Music Institute are among the many online teaching services available. These instruments include:

String

Stringed instruments, known as Tat vad,[21] are as follows:

- Rabab (ਰਬਾਬ; Rabāba): Gifted by Bebe Nanaki and played by Bhai Mardana on his travels accompanying Guru Nanak. The Sikh rabab was traditionally a local Punjabi variant of the North Indian seni rabab[22] known as the 'Firandia' rabab (Punjabi: ਫਿਰੰਦੀਆ ਰਬਾਬ Phiradī'ā rabāba),[23][24][25][26][27] however Baldeep Singh, an expert in the Sikh musical tradition, challenges this narrative.[28][29]

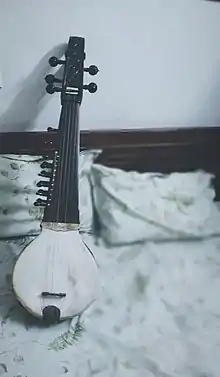

Firandia-style Rabab

Firandia-style Rabab - Saranda (ਸਰੰਦਾ; Saradā): created and played by Guru Arjan Dev[30][31][32][33][34]

- Sarangi (ਸਾਰੰਗੀ; Sāragī: meaning "a hundred colours"): promoted by Guru Hargobind to establish the Dhadi Jatha tradition at Akal Takht Sahib. Also associated with Guru Har Rai.[35][36][37][38][39][40]

- Taus (ਤਾਊਸ; Tā'ūsa: meaning "peacock" in Persian):

- Dilruba (ਦਿਲਰੁਬਾ; Dilarubā: meaning "Heart-thief" in Persian): created and played by Guru Gobind Singh when his soldiers asked him for a smaller, more portable version of the Taus

- Israj (ਇਸਰਾਜ; Isarāja): smaller version of Dilruba

- Surmandal

- Sitar[41] (ਸਿਤਾਰ)

- Dotara (ਦੁਤਾਰਾ)

- Tambura (ਤੰਬੂਰਾ/ਤਾਨਪੁਰਾ; Tabūrā/Tānapurā)

Percussion

Percussion instruments, known as Avanad vad,[42] are:

- Jori (ਜੋੜੀ; Jōṛī): creation traditionally attributed to Satta and Balwand in the court of Guru Arjan Sahib by splitting the Mardang into two individual instruments[43][44]

- Pakhawaj (ਪਖਾਵਜ; Pakhāvaja)

- The Nagara drum is also required in every Gurdwara according to the Sikh Rehat Maryada.[45]

Nagara drum

Nagara drum

Wind

Wind instruments, known as Sushir vad,[46] are:

Idiophones

Idiophone instruments, known as Ghan vad, are also commonly used, especially in folk forms of Sikh music.

See also

References

- Kaur, Inderjit N. (2011). "Sikh Shabad Kīrtan and Gurmat Sangīt: What's in the Name?" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. University of California, Santa Cruz. 18 (1–2): 251–278 – via ebscohost.

- van der Linden, Bob (2011-12-01). "Sikh Sacred Music, Empire and World Music". Sikh Formations. 7 (3): 383–397. doi:10.1080/17448727.2011.637364. ISSN 1744-8727. S2CID 219697855.

- Paintal, Ajit Singh. Sikh Devotional Music – Its Main Traditions (PDF).

- "Guru Nanak Sahib Ji And Bhai Mardana Ji – Gateway To Sikhism". 2014-02-26. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- Nair, Malini (2022-06-02). "Why attempts to revive traditional Sikh instruments at gurdwaras have failed for 90 years". Scroll.in. Retrieved 2023-08-12.

- "Raags of Sri Guru Granth Sahib". Raj Academy. 2021-12-29. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "Official Website of Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee, Sri Amritsar – Sri Guru Granth Sahib". Archived from the original on 2021-01-07. Retrieved 2020-12-16.

- "Saaj (Musical Instruments) | Discover Sikhism". www.discoversikhism.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- Singh, T. "Some Technical Terms Used In The Gurbani". www.gurbani.org. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- Singh, T. "Some Technical Terms Used In The Gurbani". www.gurbani.org. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "ਲੋਕ ਸਾਜ਼ – ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਪੀਡੀਆ". punjabipedia.org (in Punjabi). Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Saaj (Musical Instruments) | Discover Sikhism". www.discoversikhism.com. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- PTI (2022-05-25). "SGPC to revive 'gurbani kirtan' with string instruments in Golden Temple". ThePrint. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- "Tanti Saaj – Sri Gurmat Academy". Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- Singh, Gurnam; Singh, Kanwaljit; Singh, Amandeep. "Learning of Gurmat Sangeet >> ਗੁਰਮਤਿ ਸੰਗੀਤ ਦੀ ਸਾਜ਼ ਪਰੰਪਰਾ". Gurmat Gyan Online Study Centre – Punjabi University of Patiala. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Music of India, Chief Editor : Late Pandit Nikhil Ghosh published by OXFORD Press.

- ਕਾਨ੍ਹ ਸਿੰਘ ਨਾਭਾ (ਭਾਈ), ਗੁਰ ਸ਼ਬਦ ਰਤਨਾਕਰ ਮਹਾਨ ਕੋਸ਼, ਭਾਸ਼ਾ ਵਿਭਾਗ, ਪੰਜਾਬ, 2011 (in Punjabi)

- ਗੁਰਮਤਿ ਸੰਗੀਤ ਤਕਨੀਕੀ ਸ਼ਬਦਾਵਲੀ, ਗੁਰਨਾਮ ਸਿੰਘ (ਡਾ.) ਮੁੱਖ ਸੰਪਾ., ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਯੂਨੀਵਰਸਿਟੀ ਪਟਿਆਲਾ, 2012. (in Punjabi)

- ਗੁਰਮਤਿ ਸੰਗੀਤ ਪਰਬੰਧ ਤੇ ਪਾਸਾਰ, ਗੁਰਨਾਮ ਸਿੰਘ (ਡਾ.), ਪੰਜਾਬੀ ਯੂਨੀਵਰਸਿਟੀ, ਪਟਿਆਲਾ, 2000. (in Punjabi)

- "Musical Instruments in Gurbani Sangeet- SearchGurbani.com". www.searchgurbani.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Stringed Instruments in Gurbani Sangeet- SearchGurbani.com". www.searchgurbani.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Seni Rabab". chandrakantha.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Rabab". Sikh Musical Heritage – The Untold Story. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- "Raj Academy | Rabab". Raj Academy. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- "Rabab". SIKH SAAJ. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- "Sikh Instruments-The Rabab". Oxford Sikhs. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- "Learning of Gurmat Sangeet >> Musical Instruments of Gurmat Sangeet". gurmatgyanonlinepup.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- Bharat Khanna (Nov 1, 2019). "Punjabi varsity's Firandia rabab helps revival of string instrument | Ludhiana News – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- Singh, Baldeep (2012-06-27). "Rabab goes shopping…". The Anād Foundation. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- "Saranda". SIKH SAAJ. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "Saranda | Discover Sikhism". www.discoversikhism.com. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "Sikh Instrument-The Saranda". Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "Raj Academy | Saranda". Raj Academy. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "Saranda". Sikh Musical Heritage – The Untold Story. Retrieved 2022-08-30.

- "Kirtan: Singing to the Divine – Esplanade Offstage".

- "Canadian Sikh Heritage | Sikh Music".

- "Saaj (Musical Instruments) | Discover Sikhism".

- "Classical Indian Musical Instruments for Kirtan".

- https://www.sikhsaaj.com/

- "Raj Academy | Instruments".

- "Canadian Sikh Heritage | Sikh Music". Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Percussion Instruments in Gurbani Sangeet- SearchGurbani.com". www.searchgurbani.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Raj Academy | Jori". Raj Academy. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Jori | Discover Sikhism". www.discoversikhism.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Sikh Reht Maryada, the Definition of Sikh, Sikh Conduct & Conventions, Sikh Religion Living, India".

- "Wind Instruments in Gurbani Sangeet- SearchGurbani.com". www.searchgurbani.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- "Sikh Saaj | Other | Tabla – Discover Sikhism". www.discoversikhism.com. Retrieved 2022-08-31.