Yadav

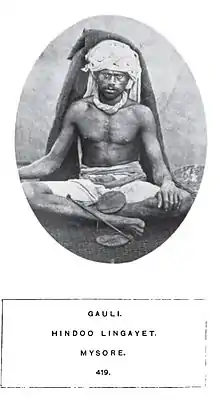

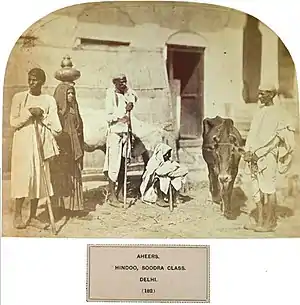

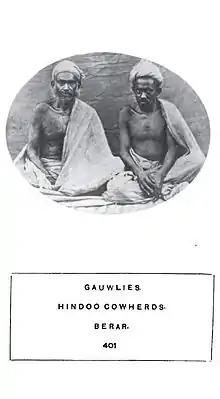

Yadav refers to a grouping of traditionally non-elite,[1][2] peasant-pastoral communities or castes in India that since the 19th and 20th centuries[3][4] have claimed descent from the mythological king Yadu as a part of a movement of social and political resurgence.[5] The term Yadav now covers many traditional peasant-pastoral castes such as Ahirs of the Hindi belt and the Gavli of Maharashtra.[1][6]

| Yadav | |

|---|---|

| Languages | Hindi, Urdu, Haryanvi, Punjabi, Telugu, Tamil, Gujarati, Rajasthani, Bhojpuri, Marwari, Kannada, Odia, Bengali |

| Region | Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, West Bengal, Assam, Odisha Bihar, Jharkhand, Nepal Delhi, Mauritius, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh |

Historically, the Ahir and Yadav groups had an ambiguous ritual status in caste stratification.[7][lower-alpha 1] Since the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Yadav movement has worked to improve the social standing of its constituents,[9] through Sanskritisation,[10] active participation in the armed forces,[3] expansion of economic opportunities to include other, more prestigious business fields, and active participation in politics.[9] Yadav leaders and intellectuals have often focused on their claimed descent from Yadu, and from Krishna,[11] which they argue confers kshatriya status upon them,[12] and effort has been invested in recasting the group narrative to emphasise kshatriya-like valour,[13] however, the overall tenor of their movement has not been overtly egalitarian in the context of the larger Indian caste system.[14] Yadavs benefited from Zamindari abolition in some states of north India like Bihar, but not to the extent that members of other Upper Backward Castes did.[15]

Origins

In mythology

The term Yadav (or sometimes Yadava) has been interpreted to mean a descendant of Yadu, who is a mythological king.[16]

Using "very broad generalisations", Jayant Gadkari says that it is "almost certain" from analysis of the Puranas that Andhaka, Vrishni, Satvata and Abhira were collectively known as Yadavas and worshipped Krishna. Gadkari further notes of these ancient works that "It is beyond dispute that each of the Puranas consists of legends and myths ... but what is important is that, within that framework [a] certain value system is propounded".[17]

Lucia Michelutti notes that

At the core of the Yadav community lies a specific folk theory of descent, according to which all Indian pastoral castes are said to descend from the Yadu dynasty (hence the label Yadav) to which Krishna (a cowherder, and supposedly a Kshatriya) belonged. ... [there is] a strong belief amongst them that all Yadavs belong to Krishna's line of descent, the Yadav subdivisions of today being the outcome of a fission of an original and undifferentiated group.[18]

Historians such as P. M. Chandorkar have used epigraphical and similar evidence to argue that Ahirs and Gavlis are representative of the ancient Yadavas and Abhiras mentioned in Sanskrit works.[19]

In practice

There are several communities that coalesce to form the Yadavs. Christophe Jaffrelot has remarked that

The term 'Yadav' covers many castes which initially had different names: Ahir in the Hindi belt, Punjab and Gujarat, Gavli in Maharashtra, Golla in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka etc. Their traditional common function, all over India, was that of herdsmen, cowherds and milksellers.[6]

However, Jaffrelot has also said that most of the modern Yadavs are cultivators, mainly engaged in tilling the land, and less than one third of the population are occupied in raising cattle or the milk business.[20]

M. S. A. Rao had earlier expressed the same opinion as Jaffrelot, and noted that the traditional association with cattle, together with the belief in descent from Yadu, defines the community.[16] According to David Mandelbaum, the association of the Yadav (and their constituent castes, Ahir and Gwala) with cattle has impacted on their commonly viewed ritual status (varna) as Shudra, although the community's members often claim the higher status of Kshatriya. The Shudra status is explained by the nomadic nature of herdsmen, which constrained the ability of other groups in the varna system to validate the adherence to practices of ritual purity; by their involvement in castration of the animals, which was considered to be a ritually polluting act; and because the sale of milk, as opposed to personal use thereof, was thought to represent economic gain from a sacrosanct product.[21]

According to Lucia Michelutti:

... Yadavs constantly trace their caste predispositions and skills to descent, and in doing so they affirm their distinctiveness as a caste. For them, caste is not just appellation but quality of blood (Yalman 1969: 87, in Gupta 2000: 82). This view is not recent. The Ahirs (today Yadavs) had a lineage view of caste (Fox 1971; Unnithan-Kumar 1997) that was based on a strong ideological model of descent. This descent-based kinship structure was also linked to a specific Kshatriya and their religious tradition centred on Krishna mythology and pastoral warrior hero-god cults.[22]

Yadavs in modern India

Occupational background, location and social status

The Yadavs mostly live in Northern India, and particularly in Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.[23][24] Traditionally, they were a non-elite[25][2] pastoral caste. Their traditional occupations changed over time and for many years Yadavs have been primarily involved in cultivation,[26] although Michelutti has noted a "recurrent pattern" since the 1950s whereby economic advancement has progressed through involvement in cattle-related business to transportation and thence to construction. Employment with the army and the police have been other traditional occupations in northern India, and more recently government employment in that region has also become significant. She believes that positive discrimination measures and gains as a consequence of land reform legislation have been important factors in at least some areas.[27]

Lucia Michelutti notes that

Colonial ethnographers left a legacy of hundreds of pages of ethnographic and ethnological details which portray the Ahir/Yadavs as "Kshatriyas", "martial" and "wealthy", or as "Shudras", "cowherders", "milk sellers" and low in status terms. In short there has been no consensus on the nature of the Ahir caste/tribe.[28]

J. S. Alter notes that in North India the majority of the wrestlers are of the Yadav caste. He explains this as being due to their involvement in the milk business and dairy farms, which thus provides easy access to the milk and ghee deemed to be essential to a good diet.[29]

Although the Yadavs have formed a fairly significant proportion of the population in various areas, including 11% of that of Bihar in 1931, their interest in pastoral activities was not traditionally matched by ownership of land and consequently they were not a "dominant caste". Their traditional position, which Jaffrelot describes as "low caste peasants", also militated against any dominant role. Their involvement in pastoralism accounts for a traditional view of Yadavs as being peaceful, while their particular association with cows has a special significance in Hinduism, as do their beliefs regarding Krishna.[26] Against this image, Russell and Lal, writing in 1916, called the Ahir subdivision uncouth, although it is unclear whether their comments were based entirely on proverbial stories, on observation or on both.[30] Tilak Gupta said that this view persisted in modern times in Bihar, where the Yadav were viewed in highly negative terms by other groups.[31] However, Michelutti observed, these very same people acknowledge and coveted their political influence, connections and abilities.[32]

The Yadavs have, however, demonstrated a feature, driven by their more notable members, that shares a similarity with other Indian communities. Mandelbaum has noted that

As the families of a jāti, in sufficient number, accrue a strong power base, and as their leading men become united enough to move together for higher status, they typically step up their efforts to improve their jāti customs. They try to abandon demeaning practices and to adopt purer and more prestigious ways. They usually want to drop the old name for a better one.[24]

In Bihar, the political advancement of Yadavs didn't improve their relative marginalisation in other fields. The spread of education among the community remained less as compared to more advanced Other Backward Castes like Awadhia Kurmi, Koeri and Bania. The attachment of Yadavs with the pastoral activities has been responsible behind their lower position in caste hierarchy as compared to owner cultivator castes among the OBCs. In areas where the communal ownership of land prevailed, trespassing into the fields by Yadav cattle herders to feed the cattle remained the part of their daily struggle for survival. Since such communal lands were mostly appropriated by village landlords, the caste occupation of Yadavs brought them in conflict with latter, and such skirmishes gave a militant and aggressive edge to the community's character. This followed their portrayal as "uncultured brutes" in the elitist discourses, which largely mirrors extreme backwardness still prevalent in large section of this community. The attempt to move up in the social ladder also remained evident in the nature of community and in due course of time "thriftiness" was observed to be a phenomenon, where they tried to save and buy small plot of lands, to be classified as owner cultivators.[33]

Sanskritisation

By the end of the nineteenth century, some Yadavs had become successful cattle traders and others had been awarded government contracts to care for cattle.[34] Jaffrelot believes that the religious connotations of their connections to the cow and Krishna were seized upon by those Yadavs seeking to further the process of Sanskritisation,[26] and that it was Rao Bahadur Balbir Singh, a descendant of the last Abhira dynasty to be formed in India, who spearheaded this. Singh established the Ahir Yadav Kshatriya Mahasabha (AYKM) in 1910, which at once asserted that its Ahir constituents were of Kshatriya ritual rank in the varna system, descended from Yadu (as was Krishna), and really known as Yadavs. The organisation claimed support from the facts that various Raj ethnologists had earlier claimed a connection between the Ahir and the Abhira, and because their participation in recent events such as the Indian Rebellion of 1857 had demonstrated that Ahirs were good fighters.[35]

The AYKM was a self-contained unit and did not try to forge links with similar bodies among other caste groups that claimed Kshatriya descent at that time. It had some success, notably in breaking down some of the very strict traditions of endogamy within the community, and it gained some additional momentum as people from rural areas gradually migrated away from their villages to urban centres such as Delhi. Ameliorating the effects of strict endogamy was seen as being conducive to causing the community as a whole to unite, rather than existing as smaller subdivisions within it.[35] Rao has said that the events of this period meant that "the term Yadava refers to both an ethnic category and an ideology".[36]

Of particular significance in the movement for Sanskritisation of the community was the role of the Arya Samaj, whose representatives had been involved with the family of Singh since the late 1890s and who had been able to establish branches in various locations.[35] Although this movement, founded by Swami Dayananda Saraswati, favoured a caste hierarchy and also endogamy, its supporters believed that caste should be determined on merit rather than on heritage. They therefore encouraged Yadavs to adopt the sacred thread as a symbolic way to defy the traditional inherited caste system, and they also supported the creation of cow protection associations (Goraksha Sabha) as a means by which Yadavs and other non-Brahmans could affirm the extent of their commitment to Hinduism by observing the strictures relating to cow slaughter.[37] In Bihar, where the Bhumihars and Rajputs were the dominant groups, the wearing of the thread by Ahirs led to occasions of violence.[38]

Jaffrelot has contrasted the motivations of Yadav Sanskritisation with that of the Nairs, another Indian community. He notes that Gyanendra Pandey, Rao and M. N. Srinivas all assert that Yadav Sanskritisation was not a process to imitate or raise the community to ritual parity with the higher ranks but rather to undermine the authority of those ranks. He contrasts this "subversion" theory with the Nair's motive of "emancipation", whereby Sanskritisation was "a means of reconciling low ritual status with growing socio-economic assertiveness and of taking the first steps towards an alternative, Dravidian identity". Using examples from Bihar, Jaffrelot demonstrates that there were some organised attempts among members of the Yadav community where the driving force was clearly secular and in that respect similar to the Nair's socio-economic movement. These were based on a desire to end oppression caused by, for example, having to perform begari (forced labour) for upper castes and having to sell produce at prices below those prevailing in the open market to the zamindars, as well as by promoting education of the Yadav community. This "aggressive Sanskritisation", which caused riots in the area, was emulated by some other of the lower caste groups.[37] In support of the argument that the movements bore similarity, Jaffrelot cites Hetukar Jha, who says of the Bihar situation that "The real motive behind the attempts of the Yadavas, Kurmis and Koeris at Sanskritising themselves was to get rid of this socio-economic repression".[39]

The process of Sanskritisation often included creating a history. The first such for the Yadavs was written in the late nineteenth century by Vithal Krishnaji Khedkar, a schoolteacher who became private secretary to a Maharajah. In 1959, Khedekar's work was published by his son, Raghunath Vithal Khedkar, who was a surgeon, under the title The Divine Heritage of the Yadavas. There has been subsequent work to develop his ideas, notably by K. C. Yadav and J. N. Singh Yadav.[24][40]

Khedekar's history made the claim that Yadavs were descendants of the Abhira tribe and that the modern Yadavs were the same community referred to as dynasties in the Mahabharata and Puranas.[40] Describing the work of the Khedekars as "a well-edited and well-produced volume", Mandelbaum notes that the Yadavs

... have usually been held in considerably less glorious repute by their neighbors. While an occasional warrior of a pastoral jati did establish his own state and dynasty, cattlekeepers are ranked in many localities among the lower blocks of the Shudras ... [The book] postulates divine and noble ancestry for a good many jatis in several language regions covering hundreds and thousands of people who share little more than a traditional occupation and a conviction about their rightful prerogatives.[24]

In creating this history there is some support for an argument that Yadavs were looking to adopt an ethnic identity akin to the Dravidian one that was central to the Sanskritisation of the Nairs and other in south India. However, Jaffrelot believes that such an argument would be overstated because the Yadav "redrawing of history" was much more narrow, being centred on themselves rather than on any wider shared ethnic base. They did acknowledge groups such as the Jats and Marathas as being similarly descended from Krishna but they did not particularly accommodate them in their adopted Aryan ethnic ideology, believing themselves to be superior to these other communities. Jaffrelot considers the history thus created to be one that is "largely mythical [and] enabled Yadav intellectuals to invent a golden age".[40]

Michelutti prefers the term "yadavisation" to that of "sanskritisation". She argues that the perceived common link to Krishna was used to campaign for the official recognition of the many and varied herding communities of India under the title of Yadav, rather than merely as a means to claim the rank of Kshatriya. Furthermore, that "... social leaders and politicians soon realised that their 'number' and the official proof of their demographic status were important political instruments on the basis of which they could claim a 'reasonable' share of state resources."[18]

All-India Yadav Mahasabha

The All-India Yadav Mahasabha (AIYM) was founded at Allahabad in 1924 by a meeting of disparate local groups from Bihar, Punjab and what is now Uttar Pradesh.[34][40] Although the AIYM was initially organised by V. K. Khedakar, it was Rao Balbir Singh who developed it and this coincided with a period – during the 1920s and 1930s – when similar Sanskritisation movements elsewhere in the country were on the wane. The program included campaigning in favour of teetotalism and vegetarianism, both of which were features of higher-ranking castes, as well as promoting self-education and promoting the adoption of the "Yadav" name.[23] It also sought to encourage the British Raj to recruit Yadavs as officers in the army and sought to modernise community practices such as reducing the financial burden dowries and increasing the acceptable age of marriage. Furthermore, the AIYM encouraged the more wealthy members of the community to donate to good causes, such as for the funding of scholarships, temples, educational institutions and intra-community communications.[23][38]

The Yadav belief in their superiority impacted on their campaigning. In 1930, the Yadavs of Bihar joined with the Kurmi and Koeri agriculturalists to enter local elections. They lost badly but in 1934 the three communities formed the Triveni Sangh political party, which allegedly had a million dues-paying members by 1936. However, the organisation was hobbled by competition from the Congress-backed Backward Class Federation, which was formed around the same time, and by co-option of community leaders by the Congress party. The Triveni Sangh suffered badly in the 1937 elections, although it did win in some areas. Aside from an inability to counter the superior organisational ability of the higher castes who opposed it, the unwillingness of the Yadavs to renounce their belief that they were natural leaders and that the Kurmi were somehow inferior was a significant factor in the lack of success. Similar problems beset a later planned caste union, the Raghav Samaj, with the Koeris.[41]

In the post-colonial period, according to Michelutti, it was the process of yadavisation and the concentration on two core aims – increasing the demographic coverage and campaigning for improved protection under the positive discrimination scheme for Backward Classes – that has been a singular feature of the AIYM, although it continues its work in other areas such as promotion of vegetarianism and teetotalism. Their proposals have included measures designed to increase the number of Yadavs employed or selected by political and public organisations on the grounds of their numerical strength, including as judges, government ministers and regional governors. By 2003 the AIYM had expanded to cover seventeen states and Michelutti believed it to be the only organisation of its type that crossed both linguistic and cultural lines. It continues to update its literature, including websites, to further its belief that all claimed descendants of Krishna are Yadav. It has become a significant political force.[42]

The campaign demanding that the army of the Raj should recruit Yadavs as officers resurfaced in the 1960s. Well-reported bravery during fighting in the Himalayas in 1962, notably by the 13th Kumaon company of Ahirs, led to a campaign by the AIYM demanding the creation of a specific Yadav regiment.[38]

Post-Independence

Mandelbaum has commented on how the community basks in the reflected glory of those members who achieve success, that "Yadav publications proudly cite not only their mythical progenitors and their historical Rajas, but also contemporaries who have become learned scholars, rich industrialists, and high civil servants." He notes that this trait can also be seen among other caste groups.[43]

The Sadar festival is celebrated annually by the Yadav community in Hyderabad, following the day of Diwali. Community members parade, dancing around their best buffalo bulls, which have been colourfully decorated with flowers and paint.[44]

Classification

The Yadavs are included in the Other Backward Classes (OBCs) category in the Indian states of Bihar,[45] Chhattisgarh,[46] Delhi,[47] Haryana,[48] Jharkhand,[49] Karnataka,[50] Madhya Pradesh,[51] Odisha,[52] Rajasthan,[53] Uttar Pradesh,[54] and West Bengal.[55] In 2001, the Social Justice Committee in Uttar Pradesh reported over-representation of some OBCs, particularly Yadavs, in public offices; it suggested creating sub categories within the OBC category.[56] The outcome of this was that the Yadav/Ahir became the only group listed in Part A of a three-part OBC classification system.[57]

Yadavs in Nepal

The Central Bureau of Statistics of Nepal classifies the Yadav as a subgroup within the broader social group of Madheshi Other Caste.[58] At the time of the 2011 Nepal census, 1,054,458 people (4.0% of the population of Nepal) were Yadav. The frequency of Yadavs by province was as follows:

- Madhesh Province (14.8%)

- Lumbini Province (4.1%)

- Koshi Province (1.3%)

- Bagmati Province (0.2%)

- Gandaki Province (0.0%)

- Karnali Province (0.0%)

- Sudurpashchim Province (0.0%)

The frequency of Yadavs of Nepal was higher than national average (4.0%) in the following districts:[59]

Notes

- From the mid-19th century onward, many British ethnographies attempted to understand India's tribes and castes by attempting to document the differences and to explain them in the prevailing ideologies of the period; the lack of such understanding was felt to be one of the reasons for the Indian rebellion of 1857.[8]

References

- Susan Bayly (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 200, 383. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6. Quote: Ahir: Caste title of North Indian non-elite 'peasant'-pastoralists, known also as Yadav."

- Michelutti, Lucia (2004), "'We (Yadavs) are a caste of politicians': Caste and modern politics in a north Indian town", Contributions to Indian Sociology, 38 (1–2): 43–71, doi:10.1177/006996670403800103, S2CID 144951057 Quote: "The Yadavs were traditionally a low-to-middle-ranking cluster of pastoral-peasant castes that have become a significant political force in Uttar Pradesh (and other northern states like Bihar) in the last thirty years."

- Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6. Quote: "Gopis, Goalas, and Ahirs, who would by the early 1900s begin referring to themselves as Yadav kshatriyas, had long sought and attained (after 1898) recruitment as soldiers in the British Indian army, particularly in the Western Gangetic Plain."

- Hutton, John Henry (1969). Caste in India: its nature, function and origins. Oxford University Press. p. 113. Quote: "In a not dissimilar way the various cow-keeping castes of northern India were combining in 1931 to use the common term of Yadava for their various castes, Ahir, Goala, Gopa, etc., and to claim a Rajput origin of extremely doubtful authenticity."

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. p. 187-188. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8.

[187] The term "Yadav" covers many castes which initially had different names: Ahir in the Hindi belt, Punjab and Gujarat, Gavli in Maharashtra, Gola in Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka etc. Their traditional common function, all over India, was that of herdsman, cowherds and milksellers. [188] In practice, the Yadavs today spend most of their time tilling the land. At the turn of the century in the Central Provinces two-thirds of Ahirs were already cultivators and labourers while less than one third raised cattle and dealt with milk and milk products.

- Michelutti, Lucia (2008), The Vernacularisation of Democracy: Politics, Caste and Religion in India, Exploring the Political in South Asia, London and New York: Routledge, p. 220, ISBN 978-0-415-46732-2,

Historically, the Ahir caste/community also had an ambiguous ritual status in the caste hierarchy. Amongst the Ahir/Yadav case we find rajas, zamindars, sepoys, and cowherders who have been conceived and categorised either as warriors and as belonging to the Kshatriya varna, or as lower caste and belonging to the shudra varna. In Ahirwal, members of Ahir seigneurial lineages have come to be known by the title Rajput. (p. 220)

- Rand, Gavin (6 June 2013), "Reconstructing the Imperial Military after the Rebellion", in Rand, Gavin; Bates, Crispin (eds.), Mutiny on the Margins: New Perspectives on the Indian Uprising of 1857, Volume 7, p. 101, ISBN 978-81-321-1053-8,

However, while ethnography was thus made central to the process of reconstruction, there remained a good deal of ambiguity regarding distinctions of race, caste and tribe. An investigation into the utility of various 'low caste' levies raised during 1857 was abandoned in 1861 when it emerged that while some officers had raised troops from sweepers and outcastes, others understood the term to refer simply to those regiments raised without Brahmins. This is simply one example of the numerous, wider ambiguities which inflect colonial knowledge in this period and which (amongst other factors) militated against radical change in the aftermath of the rebellion. This ambiguity was reflected in much of the evidence gathered by the Royal Commission, where geographic and regional distinctions overlapped and complicated religious and ethnic identities. Nevertheless, the administrative impulse to know India after 1857 is evident throughout the process of reflection and reconstruction undertaken by the imperial military. However, as the diversity of opinion gathered by the Royal Commission makes clear, while there was general recognition that ethnographic knowledge was key to the business of administering the Native army, there was much less agreement on the precise mechanisms by which such administration could be carried forth and, often, widespread confusion over the most salient aspects of Indian ethnography, culture and tradition. In part, the injunction to know India and its peoples is characteristic of the period.<Footnote 35 (p. 111)>: See, for example, the illustrated taxonomy of Indian ethnographic types prepared by Kaye, Watson, and Meadows Taylor and published as The People of India: A Series of Photographic Illustrations with Descriptive Letterpress, of the Races and Tribes of Hindustan, Originally Prepared under the Authority of the Government of India and Reproduced by the Order of the Secretary of State in Council (London: W. H. Allen, 1868)>

- Leshnik, Lawrence S.; Sontheimer, Günther-Dietz (1975). Pastoralists and nomads in South Asia. O. Harrassowitz. p. 218. ISBN 9783447015523. Quote: "The Ahir and allied cowherd castes (whether actually pastoralists or cultivators, as in the Punjab) have recently organized a pan-Indian caste association with political as well as social reformist goals using the epic designation of Yadava (or Jadava) Vanshi Kshatriya, ie the warrior caste descending from the Yadava lineage of the Mahabharata fame."

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. Columbia University Press. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-0-231-12786-8. Quote: "In his typology of low caste movements, (M. S. A.) Rao distinguishes five categories. The first is characterised by 'withdrawal and self-organisation'. ... The second one, illustrated by the Yadavs, is based on the claim of 'higher varna status' and fits with Sanskritisation pattern. ..."

- Gooptu, Nandini (1997), "The Urban Poor and Militant Hinduism in Early Twentieth-Century Uttar Pradesh", Modern Asian Studies, 31 (4 (Oct., 1997)): 879–918, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00017194, JSTOR 312848, S2CID 146484298 Quote: " ... Lord Krishna, a legendary warrior and a Hindu deity, whom some shudra castes, notably the ahir or yadav, claim to be their ancestor." (page 902)

- Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-521-79842-6. Quote: "They had many counterparts elsewhere, most notably in the Gangetic plain where users of titles like Ahir, Jat and Goala turned increasingly towards the cow-cherishing rustic piety associated with the cult of Krishna. With its visions of milkmaids and sylvan raptures, and its cultivation of divine bounty in the form of sweet milky essences, this form of Vishnu worship offered an inviting path to 'caste Hindu' life for many people of martial pastoralist background.42 Footnote 42: "From the later nineteenth century the title Yadav was widely adopted in preference to Goala. ..."

- Flueckiger, Joyce Burkhalter (1996). Gender and Genre in the Folklore of Middle India. Cornell University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-8014-8344-8. Quote: "Another way to confirm their warrior status was to try to associate themselves with Yadav cowherding caste of the divine cowherd Krishna, calling themselves Yadavs instead of Ahirs. Ahir intelligensia "rewrote" certain historical documents to prove this connection, forming a national Yadav organization that continues to coordinate and promote the mobility drive of the caste. Integral to this movement are retelling of caste history that reflect its martial character; ..."

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. Columbia University Press. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-231-12786-8. Quote: "Rather, the low caste movements can more pertinently be regrouped in two broader categories: first, the reform movements situating themselves within the Hindu way of life, be they relying on the mechanisms of Sanskritisation or on the bhakti tradition; and second those which are based on an ethnic or western ideology with a strong egalitarian overtone. The Yadav movement—and to a lesser extent the Ezhavas—can be classified in the first group whereas all the other ones belong to the second category. Interestingly none of the latter has a North Indian origin."

- Ranabir Samaddar (2016). Government of Peace: Social Governance, Security and the Problematic of Peace. Routledge. p. 169. ISBN 978-1317125372. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- Rao, M. S. A. (1979). Social movements and social transformation: a study of two backward classes movements in India. Macmillan. p. 124. ISBN 9780836421330.

- Gadkari, Jayant (1996). Society and religion: from Rugveda to Puranas. Bombay: Popular Prakashan. pp. 179, 183–184. ISBN 978-81-7154-743-2.

- Michelutti, Lucia (February 2004). ""We (Yadavs) are a caste of politicians": Caste and modern politics in a north Indian town". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 38 (1–2): 49. doi:10.1177/006996670403800103. S2CID 144951057.(subscription required)

- Guha, Sumit (2006). Environment and Ethnicity in India, 1200-1991. University of Cambridge. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-521-02870-7.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8.

- Mandelbaum, David Goodman (1970). Society in India. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 442–443. ISBN 978-0-520-01623-1.

- Gupta, Dipankar; Michelutti, Lucia (2004). "2. 'We (Yadavs) are a caste of politicians': Caste and modern politics in a north Indian town". In Dipankar Gupta (ed.). Caste in Question: Identity or hierarchy?. Vol. Contributions to Indian Sociology. New Delhi, California, London: Sage Publications. pp. 48/Lucia Michelutti. ISBN 0-7619-3324-7.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- Mandelbaum, David Goodman (1970). Society in India. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 442. ISBN 978-0-520-01623-1.

- Luce, Edward (2008). In Spite of the Gods: The Rise of Modern India. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-4000-7977-3. Quote: "The Yadavs are one of India's largest 'Other Backward Classes,' a government term that covers most of India's Sudra castes. Yadavs are the traditional cowherd caste of North India and are relatively low down on the traditional pecking order, but not as low as the untouchable Mahars or Chamars."

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8.

- Michelutti, Lucia (February 2004). ""We (Yadavs) are a caste of politicians": Caste and modern politics in a north Indian town". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 38 (1–2): 52–53. doi:10.1177/006996670403800103. S2CID 144951057.(subscription required)

- Michelutti, Lucia (2002). "Sons of Krishna: the politics of Yadav community formation in a North Indian town" (PDF). p. 83. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Michelutti, Lucia (2012). "Wrestling with (Body) Politics: Understanding 'Goonda' Political Styles in North India". In Price, Pamela; Ruud, Arild Engelsen (eds.). Power and Influence in India: Bosses, Lords and Captains: Exploring the Political in South Asia. Routledge. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-13619-799-4.

- Russell, R. V.; Lal, Raj Bahadur Hira (1916). Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India. Vol. 2. London: Macmillan. p. 37.

- Gupta, Tilak D. (27 June 1992). "Yadav Ascendancy in Bihar Politics". Economic and Political Weekly. 27 (26): 1304–1306. JSTOR 4398537.(subscription required)

- Michelutti. "Wrestling with (body) politics: understanding 'goonda' political styles in North India". Quote:"I saw many high-caste people, who refer to Yadavs as goondas in a disapproving fashion using their 'services'. Their connections, political influence and abilities are thus practically acknowledged. By the end of the fieldwork the same non-Yadav informants who advise me of not going around with politicians asked me to use my 'Yadav contacts' to help them to get their telephone line sorted out, to get a taxi-licence or to speed up a court case.". Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- Gupta., Tilak D. (1992). ""Yadav Ascendancy in Bihar Politics."". Economic and Political Weekly. 27 (26): 1304–06. JSTOR 4398537.

- Mandelbaum, David Goodman (1970). Society in India. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 443. ISBN 978-0-520-01623-1.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- Rao, M. S. A. (1979). Social movements and social transformation: a study of two backward classes movements in India. Macmillan. p. 123. ISBN 9780836421330.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. pp. 191–193. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- Mandelbaum, David Goodman (1970). Society in India. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-520-01623-1.

- Jha, Hetukar (1977). "Lower Caste Peasants and Upper-Caste Zamindars in Bihar, 1921–1925: an analysis of sanskritisation and contradiction between the two groups". Indian Economic and Social History Review. 14 (4): 550. doi:10.1177/001946467701400404. S2CID 143558861.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. pp. 194–196. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India. London: C. Hurst & Co. p. 197. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- Michelutti, Lucia (February 2004). ""We (Yadavs) are a caste of politicians": Caste and modern politics in a north Indian town". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 38 (1–2): 50–51. doi:10.1177/006996670403800103. S2CID 144951057.(subscription required)

- Mandelbaum, David Goodman (1970). Society in India. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 485. ISBN 978-0-520-01623-1. Retrieved 25 August 2011.

- "Traditional Sadar Festival Celebrated". The Hindu. Hyderabad. 7 November 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF BIHAR" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 104)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES: CHHATISGARH" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 1)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES: DELHI" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 3)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES: HARYANA" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 29)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES: JHARKHAND" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 118)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES: KARNATAKA" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 58)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OTHER BACKWARD CLASSES: MADHYA PRADESH" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 1)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF ORISSA" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 43)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF RAJASTHAN" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 1)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF UTTAR PRADESH" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 1)

- "CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF WEST BENGAL" (PDF), National Commission of Backward Classes, Government of India, retrieved 28 October 2011 (Serial Number 3)

- Jeffery, Roger; Jeffrey, Craig; Lerche, Jens (2014). Development Failure and Identity Politics in Uttar Pradesh. SAGE Publications India. p. 43. ISBN 9789351501800.

- Verma, Anil K. (2007). "Backward-Caste Politics in Uttar Pradesh: An Analysis of the Samajwadi Party". In Pai, Sudha (ed.). Political process in Uttar Pradesh: identity, economic reforms, and governance. Pearson Education India. p. 160. ISBN 978-81-317-0797-5.

- Population Monograph of Nepal, Volume II

- 2011 Nepal Census, District Level Detail Report