American upper class

The American upper class is a social group within the United States consisting of people who have the highest social rank, primarily due to economic wealth.[1][2] The American upper class is distinguished from the rest of the population due to the fact that its primary source of income consists of assets, investments, and capital gains rather than wages and salaries. The American upper class is estimated to include 1–2% of the population.

Definitions

The American upper class is seen by some as simply being composed of the wealthiest individuals and families in the country. The American upper class can be broken down into two groups: people of substantial means with a history of family wealth going back a century or more (called "old money") and people who have acquired their wealth more recently (e.g. since 1946), sometimes referred to as "Nouveau riche".[3][4]

The main distinguishing feature of this class, which includes an estimated 1% of the population, is the source of income. While the vast majority of people and households derive their income from wages or salaries, those in the upper class derive their primary income from investments and capital gains.[4] Estimates for the size of this group commonly vary from 1% to 2%, based on wealth.[3]

The rich constitute roughly 5% of U.S. households and their wealth is largely in the form of home equity. Other contemporary sociologists, such as Dennis Gilbert, argue that this group is not part of the upper class but rather part of the upper middle class, as its standard of living is largely derived from occupation-generated income and its affluence falls far short of that attained by the top percentile.

Many heirs to fortunes, top business executives, CEOs, successful venture capitalists, persons born into high society, and celebrities may be considered members of the upper class. Some prominent and high-rung professionals may also be included if they attain great influence and wealth.

In a 2015 CNBC survey of the wealthiest 10 percent of Americans, 44% described themselves as middle class and 40% as upper middle class.[5][6][7] Some surveys have indicated that as many as 6% of Americans identify as "upper class." Sociologist Leonard Beeghley considers total wealth to be the only significant distinguishing feature of this class and refers to the upper class simply as "the rich."[1]

Households with a net worth of $1 million or more may be classified as members of the upper class, depending on the definition of class used. While most sociologists estimate that only 1% of households are members of the upper class, Beeghley asserts that all households with a net worth of $1 million or more are considered "rich." He divides "the rich" into two sub-groups: the rich and the super-rich.

The super-rich, according to Beeghley, are those able to live off their wealth without depending on occupation-derived income. This demographic constitutes roughly 0.9% of American households. Beeghley's definition of the super-rich is congruent with the definition of upper class used by most other sociologists. The top 0.01% of the population, with an annual income of $9.5 million or more, received 5% of the income of the United States in 2007. These 15,000 families have been characterized as the "richest of the rich".[8]

The members of the tiny capitalist class at the top of the hierarchy have an influence on economy and society far beyond their numbers. They make investment decisions that open or close employment opportunities for millions of others. They contribute money to political parties, and they often own media enterprises that allow them influence over the thinking of other classes... The capitalist class strives to perpetuate itself: Assets, lifestyles, values and social networks... are all passed from one generation to the next. –Dennis Gilbert, The American Class Structure, 1998[3]

Sociologists such as W. Lloyd Warner, William Thompson, and Joseph Hickey recognize prestige differences among members of the upper class. Established families, prominent professionals, and politicians may be deemed to have more prestige than some entertainment celebrities; national celebrities, in turn, may have more prestige than members of local elites.[4] However, sociologists argue that all members of the upper class have great wealth and influence, and derive most of their income from assets rather than income.[3]

In 1998, Bob Herbert of The New York Times referred to modern American plutocrats as "The Donor Class", referring to political donations.[9][10] In 2015, the New York Times carried a list of top donors to political campaigns.[11] The Christian Science Monitor noted the class's role in GOP presidential politics in 2014.[12] Herbert had noted that it was "a tiny group – just one-quarter of 1 percent of the population – and it is not representative of the rest of the nation. But its money buys plenty of access."[9]

Theories regarding social class

Functional theorists in sociology and economics assert that the existence of social classes is necessary[4] to ensure that only the most qualified persons acquire positions of power, and to enable all persons to fulfill their occupational duties to the greatest extent of their ability. Notably, this view does not address wealth, which plays an important role in allocating status and power (see Affluence in the United States for more). According to this theory, to ensure that important and complex tasks are handled by qualified and motivated personnel, society attaches incentives such as income and prestige to those positions. The more scarce that qualified applicants are and the more essential the given task is, the larger the incentive will be. Income and prestige—which are often used to indicate a person's social class—are incentives given to that person for meeting all qualifications to complete an important task that is of high standing in society due to its functional value.[13]

It should be stressed... that a position does not bring power and prestige because it draws a high income. Rather, it draws a high income because it is functionally important and the available personnel is for one reason or another scarce. It is therefore superficial and erroneous to regard high income as the cause of a man's power and prestige, just as it is erroneous to think that a man's fever is the cause of his disease... The economic source of power and prestige is not income primarily, but the ownership of capital goods (including patents, good will, and professional reputation). Such ownership should be distinguished from the possession of consumers' goods, which is an index rather than a cause of social standing. – Kingsley Davis and Wilbert E. Moore, Principles of Stratification.

As mentioned above, income is one of the most prominent features of social class, but is not necessarily one of its causes. In other words, income does not determine the status of an individual or household, but rather reflects that status. Income and prestige are the incentives created to fill positions with the most qualified and motivated personnel possible.[13]

If... money and wealth [alone] determine class ranking... a cocaine dealer, a lottery winner, a rock star, and a member of the Rockefeller family-are all on the same rung of the social ladder... [yet most] Americans would be unwilling to accord equal rank to a lottery winner or rock star and a member of one of America's most distinguished families... wealth is not the only factor that determines a person's rank. – William Thompson, Joseph Hickey; Society in Focus, 2005.[4]

Education

Members of the upper class in American society are typically knowledgeable and have been educated in "elite" settings.[14] Wealthy parents tend to take significant efforts to ensure their children will maintain their class, often through educational opportunities unavailable to most. Upper-class parents often enroll their children in prestigious primary schools leading to similarly prestigious middle and high schools, and hopefully elite, private colleges. Often graduating from schools such as those in the Ivy League, upper class members may join exclusive clubs or fraternities.

Religion

Individuals of a broad variety of religious backgrounds have become wealthy in America. However, the majority of these individuals follow Mainline Protestant denominations; Episcopalians[15] and Presbyterians are most prevalent.[16]

Empirical distribution of income

One 2009 empirical analysis analyzed an estimated 15–27% of the individuals in the top 0.1% of adjusted gross income (AGI), including top executives, asset managers, law firm partners, professional athletes and celebrities, and highly compensated employees of investment banks.[17] Among other results, the analysis found that individuals in the financial (Wall Street) sector constitute a greater percent of the top income earners in the United States than individuals from the non-financial sector, after adjusting for the relative sizes of the sectors.

Statistics

| Top 5 states by high net worth individuals (more than $1 million, in 2009)[19] | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Percentage of millionaire households | Number of millionaire households |

| Hawaii | 6.4% | 28,363 |

| Maryland | 6.3% | 133,299 |

| New Jersey | 6.2% | 197,694 |

| Connecticut | 6.2% | 82,837 |

| Virginia | 5.5% | 166,596 |

| Bottom 5 states by high net worth individuals (more than $1 million, in 2009)[19] | ||

|---|---|---|

| State | Percentage of millionaire households | Number of millionaire households |

| South Dakota | 3.4% | 10,646 |

| Kentucky | 3.3% | 57,059 |

| West Virginia | 3.3% | 24,941 |

| Arkansas | 3.1% | 35,286 |

| Mississippi | 3.1% | 33,792 |

See also

- African-American upper class

- American gentry

- Boston Brahmin

- Colonial families of Maryland

- Donor class

- Executive compensation in the United States

- First Families of Virginia

- The Four Hundred (Gilded Age)

- Household income in the United States

- Income inequality in the United States

- Old Philadelphians

- Planter class

- Social class in the United States

- Social Register

- Upper Ten Thousand

- Wealth in the United States

- White Anglo-Saxon Protestants

Notes and references

- Beeghley, Leonard (2004). The Structure of Social Stratification in the United States. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 0-205-37558-8.

- "Upper class".

- Gilbert, Dennis (1998). The American Class Structure. New York: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 0-534-50520-1.

- Thompson, William; Joseph Hickey (2005). Society in Focus. Boston, MA: Pearson. ISBN 0-205-41365-X.

- "Millionaires say they're middle class"

- Who is middle class and why it matters Forbes, 4 August 2015

- The Middle class Millionaire

- "The Richest of the Rich, Proud of a New Gilded Age", article by Louis Uchitelle, The New York Times, July 15, 2007.

- Herbert, Bob (July 19, 1998). "The Donor Class". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Confessore, Nicholas; Cohen, Sarah; Yourish, Karen (October 10, 2015). "The Families Funding the 2016 Presidential Election". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Lichtblau, Eric; Confessore, Nicholas (October 10, 2015). "From Fracking to Finance, a Torrent of Campaign Cash – Top Donors List". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- McCutcheon, Chuck (December 26, 2014). "Why the 'donor class' matters, especially in the GOP presidential scrum". "The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- Levine, Rhonda (1998). Social Class and Stratification. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-8543-8.

- Doob, B. Christopher (2013). Social Inequality and Social Stratification in US Society (1st ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-205-79241-2.

- B. Drummond Ayres Jr. (2011-12-19). "The Episcopalians: An American Elite with Roots Going Back to Jamestown". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- Davidson, James D.; Pyle, Ralph E.; Reyes, David V. (1995). "Persistence and Change in the Protestant Establishment, 1930–1992". Social Forces. 74 (1): 157–75 [p. 164]. doi:10.1093/sf/74.1.157. JSTOR 2580627.

- Kaplan SN, Rauh J. (2009). Wall Street and Main Street: What Contributes to the Rise in the Highest Incomes?. Review of Financial Studies.

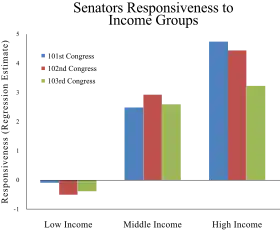

- Based on Larry Bartels's study Economic Inequality and Political Representation Archived 2011-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, Table 1: Differential Responsiveness of Senators to Constituency Opinion.

- Phoenix Marketing International Research Shows Steep Decline In Millionaires in U.S.

Further reading

- Baltzell, E. Digby. Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a New Upper Class (1958).

- Beckert, Sven. The Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896 (2003).

- Brooks, David. Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There (2010)

- Burt, Nathaniel. The Perennial Philadelphians: The Anatomy of an American Aristocracy (1999).

- Cookson, Peter W. and Caroline Hodges Persell: Preparing for Power: America's Elite Boarding Schools, Basic Books, 1989, ISBN 0-465-06269-5

- Davis, Donald F. "The Price of Conspicious [sic] Production: The Detroit Elite and the Automobile Industry, 1900-1933." Journal of Social History 16.1 (1982): 21-46. online

- Farnum, Richard. "Prestige in the Ivy League: Democratization and discrimination at Penn and Columbia, 1890-1970." in Paul W. Kingston and Lionel S. Lewis, eds. The high-status track: Studies of elite schools and stratification (1990).

- Foulkes, Nick. High Society: The History of America's Upper Class, (Assouline, 2008) ISBN 2759402886

- Fraser, Steve and Gary Gerstle, eds. Ruling America: A History of Wealth and Power in a Democracy, Harvard UP, 2005, ISBN 0-674-01747-1

- Ghent, Jocelyn Maynard, and Frederic Cople Jaher. "The Chicago Business Elite: 1830–1930. A Collective Biography." Business History Review 50.3 (1976): 288-328. online

- Hood. Clifton. In Pursuit of Privilege: A History of New York City's Upper Class and the Making of a Metropolis (2016). covers 1760-1970.

- Ingham, John N. The Iron Barons: A Social Analysis of an American Urban Elite, 1874-1965 (1978)

- Jaher, Frederic Cople, ed. The Rich, the Well Born, and the Powerful: Elites and Upper Classes in History (1973), essays by scholars

- Jaher, Frederick Cople. The Urban Establishment: Upper Strata in Boston, New York, Chicago, Charleston, and Los Angeles (1982).

- Jensen, Richard. "Family, Career, and Reform: Women Leaders of the Progressive Era." in Michael Gordon, ed., The American Family in Social-Historical Perspective,(1973): 267-80.

- Lundberg, Ferdinand: The Rich and the Super-Rich: A Study in the Power of Money Today (1968)

- McConachie, Bruce A. "New York operagoing, 1825-50: creating an elite social ritual." American Music (1988): 181-192. online

- Ostrander, Susan A. (1986). Women of the Upper Class. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-0-87722-475-4.

- Phillips, Kevin P. Wealth and Democracy: A Political History of the American Rich, Broadway Books 2003, ISBN 0-7679-0534-2

- Story, Ronald. (1980) The Forging of an Aristocracy: Harvard & the Boston Upper Class, 1800-1870

- Synnott, Marcia. The Half-Opened Door: Discrimination and Admissions at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, 1900–1970 (2010).

- Williams, Peter W. Religion, Art, and Money: Episcopalians and American Culture from the Civil War to the Great Depression (2016), especially in New York City